Abstract

PURPOSE

To determine the feasibility of an acupuncture clinical trial to prevent radiation therapy (RT) -induced fatigue.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey study and a single arm acupuncture clinical trial among patients undergoing RT. Patients with a Karnofsky score of less than 60, severe anemia, or substantial psychological diagnoses were excluded. Patients received up to 12 treatments of acupuncture over the entire course of their RT. Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS) was administered at baseline, in the middle and at the end of RT, along with the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC).

RESULTS

Among the 48/53 (91% response rate) survey participants, 20(42%) reported they would participate if the study were available, 13(27%) would not participate and 15 (31%) were unsure. Among the 16 trial participants, average fatigue and energy domains of the LFS remained stable during and after RT without any expected statistical decline due to RT. Based on PGIC at the end of RT, two subjects (13%) reported fatigue being worse, 8 (50%) stable and 6 (37%) better.

Conclusion

Acupuncture has the potential to prevent RT-related fatigue, which will need to be confirmed by conducting a randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: ACUPUNCTURE THERAPY, FATIGUE, RADIOTHERAPY/ADVERSE EFFECTS, NEOPLASMS, COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE

INTRODUCTION

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms experienced by cancer patients that negatively impacts quality of life.1 As many as 87% of patients experience fatigue symptoms while undergoing treatment, 2 and at least 30% of patients suffer from fatigue after completing their treatment courses, in some cases for many years.3, 4, 5 Cancer-related fatigue is defined as ‘a persistent, subjective sense of tiredness related to cancer or cancer treatment that interferes with usual functioning,’ 6 and its specific etiology remains unclear.

Radiation Therapy (RT) is one cause of cancer-related fatigue. In addition, fatigue specifically induced by RT varies with tumor site, number of treatments undergone, radiation dose, and the level of fatigue before treatment.3, 2, 7 Furthermore, just as chemotherapy is an inducer of general cancer-related fatigue, concurrent chemotherapy and other concurrent treatments can worsen fatigue in RT patients. 6, 8, 9

While RT clearly causes fatigue, existing therapies to address RT-related fatigue are few and limited. Studies of exercise as a way to alleviate RT-related fatigue have been mixed, in part because of non-adherence to exercise interventions, as well as a high rate of baseline exercise use in the usual care group.10 A yoga intervention study among breast cancer patients undergoing active cancer treatments (including RT) showed no significant improvement in reported fatigue over waitlist control, despite some positive effects in other domains of quality of life (QOL).11 Other multidisciplinary interventions, primarily involving behavioral modification, were not found to be very effective either. Administering exercise programs and educating patients on managing their energy and activities were both found to offer a modest benefit, but the magnitude of symptom improvement was limited and the nature of the sample made it difficult to generalize results to varying population groups.8, 9 Thus, finding an effective intervention to prevent and treat RT-related fatigue is critically needed.

One of the most common reasons that people choose acupuncture in the U.S. is to treat fatigue.12 Studies of acupuncture for chronic fatigue in the general population showed promise, although they were limited in the rigor of their methodologies.13, 14 Several small initial studies suggested that acupuncture may be helpful for addressing cancer related-fatigue;15 however, these studies focused on post-chemotherapy fatigue.16-18 Acupuncture is currently used by 2 million adults annually in the U.S,19 and the use may be even higher among cancer patients.20 Despite tremendous interest among cancer patients in using complementary therapies to address symptoms of cancer treatment,21, 22 rigorous research is needed to guide appropriate clinical integration of complementary therapies. In order to plan for a randomized controlled trial of acupuncture to prevent RT-related fatigue, we conducted a feasibility study in two separate but related phases with the following specific aims: 1) To determine the attitudes and barriers toward participating in an acupuncture clinical trial meant to prevent RT-related fatigue; 2) To determine the feasibility of recruitment and retention to an acupuncture clinical trial for RT-related fatigue; and 3) To explore the effect and variance of acupuncture to prevent RT-related fatigue.

METHODS

We conducted a feasibility study in two phases: 1) A cross-sectional study among a convenience sample in the waiting area of a Radiation Oncology department; and 2) A phase I single arm uncontrolled and un-blinded clinical trial of acupuncture. Patients were recruited from the Radiation Oncology waiting room in the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania.

Patients were older than 18 years of age, receiving at least 6 weeks of non-palliative RT treatment, at least 14 days post-surgery, ambulatory, and had a Karnofsy score of 60 or better. Patients were excluded if they had anemia (defined as their most recent hemoglobin level being less than 8.5 or having ongoing treatment for anemia), a known brain tumor or brain metastasis (because neurocognitive changes caused by cancer or RT could impact the completion of self-reported outcomes), and recent or ongoing diagnosis of a major depressive episode.

Phase I

A research assistant pre-screened patients’ charts for eligibility and approached eligible patients in the waiting area. Patients were asked to complete a one-time self-reported questionnaire that was developed based on our previous experience with acupuncture research recruitment. Patients reported demographic information and their attitudes and barriers toward participation in acupuncture research, (see table 1).

Table 1.

Attitudes towards participating in acupuncture trial for RT-related fatigue (N=48)

| Yes (N=20) | No (N=13) | Unsure (N=15) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N(%) | N(%) | |

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 8(40%) | 4(31%) | 8(53%) |

| Age: mean | 54 | 58 | 60 |

| Race: | |||

| Black | 2(10%) | 2(15%) | 8 (53%) |

| White | 15(75%) | 11(85%) | 6 (40%) |

| Asian | 2 (10%) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1(5%) | 0 | 1(7%) |

| Currently employed | 3(16%) | 10(77%) | 3(20%) |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | 4(20%) | 4(31%) | 2(13%) |

| Tumor sites | |||

| Breast | 3 (15%) | 1(8%) | 6(40%) |

| Prostate | 4 (20%) | 4 (31%) | 3(20%) |

| Head and neck | 5 (25%) | 2 (15%) | 3(20%) |

| Lung | 3 (15%) | 2 (15%) | 1(7%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (20%) | 1(8%) | 1(7%) |

| Other | 1(5%) | 3(23%) | 1(7%) |

|

| |||

| Attitudes toward acupuncture research | |||

|

| |||

| Acupuncture would help RT-related fatigue | |||

| Yes | 8(40%) | 1(8%) | 3(20%) |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Unsure | 12(60%) | 12(92%) | 12(80%) |

| Free acupuncture is an important incentive | |||

| Yes | 16 (80%) | 3(23%) | 7(47%) |

| No | 3(15%) | 7(54%) | 1(6%) |

| Unsure | 1(5%) | 3(23%) | 7(47%) |

Abbreviations: RT, radiation therapy

Phase 2

Separated from phase I, patients interested in acupuncture were referred by radiation oncologists or staff and then screened by research assistants for eligibility. Acupuncture was performed once or twice weekly depending on the participant’s time constraints and the acupuncturists’ availability in relation to RT. Two licensed physician acupuncturists (JM and AC), who had received 300 continuing medical education training hours in acupuncture and had experience in symptom management for cancer patients, delivered the intervention. The acupuncturists selected points in a semi-standardized fashion, incorporating the baseline characteristics of the patients from the list of bilateral points LI4, ST36, SP6, KI3, PC6, LIV3, and unilateral points CV4 and CV6. No acupuncture points were placed in the radiation field. The points were very similar to those used by Vicker et al. in a study of post-cancer therapy fatigue.16 This type of semi-standardized protocol has been shown to be effective in studies of acupuncture for pain-related diseases,23 providing both a structure for replication in research settings and individual variation which reflects the clinical practice of acupuncture. The needles were inserted and manipulated until “de qi” sensation was achieved, which is typically described as a dull aching, soreness or tingling that may travel away from the needling points.24

Clinical information such as cancer type, stage of disease, RT duration, number of RT fractions, number of weeks undergoing RT, RT dose, and baseline hemoglobin and albumin were abstracted from subjects’ charts. Patients completed a baseline questionnaire on demographics. The Lee Fatigue Scale (LFS) was used as the primary outcome assessment,25 which was given at baseline, mid-treatment, end of treatment, and 1 month post-treatment. The LFS consists of 18 questions and two domains with 13 items reporting fatigue and 5 items reporting energy. The scale assesses the current state of fatigue or energy on a 0 to 10 numerical rating scale with higher numbers indicating higher fatigue as well as higher energy. The LFS was found to be reliable and valid as a measure of fatigue in both the general population and patients with cancer.25, 26 Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) was administered at the end of the intervention and one month post radiation treatment to evaluate the clinical importance of the intervention.27, 28

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 8.1 for Windows (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX). Appropriate descriptive statistics including examination of proportion, mean, median and range were performed for both phase I and phase II data. Bivariable analyses were performed to explore the potential demographic and psychological predictors of willingness to participate in acupuncture research. For phase II, because the outcome data was not normally distributed, we performed a sign-rank test to explore whether acupuncture provided in the context of ongoing RT may yield significant improvement of fatigue. All analyses were two sided.

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Pennsylvania. Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

RESULTS

Phase I – Attitudes and Barriers toward studying Acupuncture for RT-fatigue

Of the 54 eligible patients, 48(89%) agreed to participate and provided data. The sample consists of 20(42%) females, mean age of 57, 32(67%) White, 12(25%) Black, 2(4%) Asian, and 2(4%) others. Sixteen (34%) participants were employed at the time of RT. The participants were receiving non-palliative RT for the following tumor types: breast 10(21%), prostate 11(23%), head and neck 10(21%), lung 6(12%), gastrointestinal 6 (12%), and other 5(11%), with an average of RT duration of 6 to 7 weeks. Ten (21%) were receiving chemotherapy concurrently with RT.

Among the 48 participants, 20(42%) agreed to participate in a trial if it were offered, 13(27%) refused, and 15(31%) felt unsure at the time of the survey. Of the 27 patients who refused participation or felt unsure about participation in an acupuncture clinical trial, the most common cited reason for non-participation was lack of time 11 (41%), 5(19%) did not like the idea of needle puncturing as part of therapy, 2(7%) did not want more therapies, 2(7%) worried about the potential side effects of acupuncture, and only 1(4%) did not believe acupuncture would help him/her with fatigue. Six (22%) chose “other” as barriers but few provided the specific reasons.

We stratify the response to participation in an acupuncture trial by demographic and clinical characteristics along with the patients’ attitudes towards acupuncture (see table 1). Black patients were more likely to respond as “unsure” towards participating in acupuncture research. Both Asian patients responded “yes” to trial participation. Individuals who were employed at the time of the RT were more likely to refuse trial participation. Individuals who responded “yes” to acupuncture trial participation were more likely to believe acupuncture would help fatigue, and were more likely to believe in receiving acupuncture free as part of trial enrollment.

Phase II – Feasibility of Acupuncture Clinical Trial

Of the 26 patients referred to the study, three patients had major medical events and died prior to enrolling in the study, five patients were excluded because of not meeting eligibility criteria, two patients declined enrollment because of time and travel issues. Sixteen patients received acupuncture treatments. One withdrew from the study intervention after 3 sessions because of the time burden for the acupuncture treatments. Nevertheless, the subject continued to provide data and was included in the analysis. After the first three trial subjects, we modified the protocol to collect 1 month follow-up data.

The baseline demographic, clinical, and treatment-related characteristics can be seen in Table 2. Ten (63%) participants were female, median age of 62, ranging from 35 to 69, 14 (88%) were white, 2 (12%) reported “other” as their race. Participants were treated for gastrointestinal tumor (GI): 6 (38%), breast: 3(19%), gynecological (GYN): 4(25%), head & neck: 2(12%), and lung 1(6%). Participants as a group received an average of 36 fractions, and radiation dosage of 63 Gray. Baseline hemoglobin was 13.3 g/dl and albumin was 3.9 g/dl. Participants received an average of 8 acupuncture treatments throughout RT.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the clinical trial participants

| Demographic | (N=16) Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 10(63%) |

| Age: Median (range) | 62 (35, 69) |

| Race: | |

| White | 14(88%) |

| Other | 2(12%) |

| Currently employed: | 7(44%) |

| Education: | |

| High school | 5(33%) |

| College | 5(33%) |

| Graduate or professional | 5(33%) |

| Currently married: | 9(64%) |

|

| |

| Clinical | |

|

| |

| Tumor site | |

| Breast | 3(19%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 6(38%) |

| Gynecologic | 4(25%) |

| Head and neck | 2(12%) |

| Lung | 1(6%) |

| Cancer Stage | |

| I | 4(25%) |

| II | 4(25%) |

| III | 8(50%) |

| RT dose: mean | 63 Gray |

| Number fraction: mean | 36 |

| Hemoglobin | 13.3 g/dl |

| Albumin | 3.9 g/dl |

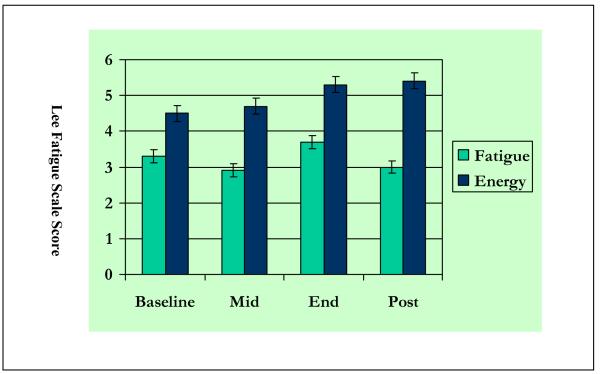

Among 16 clinical trial participants (See Figure 1), the mean fatigue score (SD) of LFS at baseline was 3.3 (1.9), at mid-RT was 2.9 (1.9), at end-RT was 3.7(1.9), and 1 month post was 3.0 (1.9). The mean energy score (SD) of LFS at baseline was 4.5 (2.5), mid-treatment 4.7 (1.8), end-RT 5.3 (1.7), and 1 month post 5.4 (2.0). In this small cohort, there was no statistically significant change of perceived fatigue or energy level in either direction. To help anchor the clinical importance of the proposed intervention, we analyzed patient Global Impression of Change (see Table 3) which demonstrated that less than 2 (13%) subjects perceived their fatigue being worse than baseline, 8(50%) perceived their fatigue being stable at the end of RT, and 6(38%) perceived their fatigue improved at the end of RT. At one month follow-up, 10 (78%) perceived their fatigue was better than baseline, 2(15%) perceived fatigue being stable, and 1(7%) perceived fatigue being worse. Small bruising and local pain were reported for some patients. No other side effects were reported.

Figure 1. Lee fatigue scale score among clinical trial participants (N=16).

We did not collect post RT data from the first 3 subjects.

Higher number indicates higher fatigue as well as higher energy

Table 3.

Patient’s global impression of fatigue as compared to baseline

| Mid-RT | End-RT | Post-RT* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Global Impression of Change | (N=16) | (N=16) | (N=13) |

| Worsened | 1(6%) | 2(13%) | 1(7%) |

| Stable | 11(69%) | 8(50%) | 2(15%) |

| Improved | 4(25%) | 6(38%) | 10(78%) |

Abbreviation: RT-radiation therapy,

We did not collect post RT data from the first 3 subjects

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that close to half of the RT patients reported they would participate in an acupuncture trial for RT-related fatigue if it were offered. Black patients tended to be more uncertain about the decision to participate in our trial. Employed patients had more time constraints dissuading them from enrolling. Amongst the small cohort of clinical trial participants, fatigue level appeared to be relatively stable as measured by the LFS; however, patients generally perceived their fatigue being stable or improved even in the context of an active RT course. Drop out was minimal in the trial and the acupuncture procedure was well-tolerated.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of the study. The first phase of the study was based on a small convenience sample from the waiting area of radiation oncology; thus, studying a bigger sample may help to confirm the impact of demographic and clinical factors on the attitudes and barriers towards enrollment in a clinical trial of acupuncture for RT-related fatigue. Secondly, we measured intended enrollment attitude, which may be different from the actual enrollment behavior. The clinical trial was single-armed, with the goal of establishing feasibility and preliminary effects. The lack of a control group cannot exclude the possibility that the findings are due to natural progression of disease or the regression to the mean effect.

Despite these limitations, this is the first acupuncture study for fatigue among patients undergoing an active RT regimen. In general, patients were open to the idea of receiving acupuncture in the context of receiving RT. Black patients tended to feel uncertain about trial enrollment which is consistent with the existing cancer therapeutic trials, which show lower trial enrollment among minority patients.29, 30 We hypothesize that factors as such distrust in medical research, unfamiliarity with acupuncture, and other social and financial issues may contribute to these patients’ “uncertainty.”29 More research is needed to understand the racial differences in trial enrollment using CAM interventions for symptom management, so that CAM therapies such as acupuncture can be used to eliminate rather than widen the disparities in symptom management among cancer patients. Employed patients tended to decline enrollment largely due to time constraints. Receiving daily RT already places severe time constraints upon these individuals, who often balance work with family in the context of active cancer treatment. Future trials may need to stratify on employment status to determine whether therapies like acupuncture (which is time consuming) have different impacts on individuals who work and who don’t work.

Among this small cohort of RT patients who received acupuncture, the severity of fatigue appeared to be stable, although it did not appear to improve beyond the baseline. This may be due to the fact that most patients’ fatigue would otherwise get worse with RT. In a large cohort study (n=372),2 70% of patients (160) who initially reported no fatigue eventually developed the symptom during RT. Furthermore, fatigue severity in the entire sample increased 37% over 5 weeks of treatment.2 In particular, GI, lung and head and neck cancer patients had higher baseline fatigue and greater increase in fatigue severity. Contrary to these findings, the majority of patients in our study who received acupuncture rated their fatigue as stable throughout their RT courses, and only 6%, 13% and 7% reported worsening symptoms at mid-RT, end-RT, and 1 month follow-up respectively. Our sample is also made up of a diverse group of GI, lung, and head and neck patients, and therefore it is conceivable that acupuncture has potential positive effects in preventing further increase of fatigue.

By conducting this feasibility acupuncture clinical trial, we learned that conducting acupuncture research in an oncology setting will require a multidisciplinary approach, benefiting from input of oncologists, acupuncturists, symptom experts, and clinical trialists. Logistically, it is much more achievable to deliver acupuncture prior to RT because of the scheduling and equipment issues involved with the radiation treatments themselves. Having a dedicated research assistant who can be involved in screening and recruitment is important for successful enrollment in the study because clinical staffs are generally overwhelmed with their clinical responsibilities. Having adequate acupuncturist coverage is also essential to the success of the trial, as this posed a difficulty in our unfunded study. In academic health centers like University of Pennsylvania, to accommodate a large number of radiation therapies and patient preferences, the RT schedule ranges from 6 AM to 8 PM. In order to efficiently recruit all eligible subjects, having one or more acupuncturist(s) cover these hours is essential to effective recruitment and retention. Because RT patients receive onsite visits weekly, follow-up is generally easy with few drop outs.

Although the etiology of RT-related fatigue is complex and not fully understood, the existing basic science knowledge of acupuncture seems to be plausible in addressing the potential mechanism of RT-related fatigue. Based on animal studies, acupuncture needling may modulate the endogenous serotonin (5-HT) system 31, 32 which is thought to contribute to fatigue.1 Additionally, recent functional imaging studies using fMRI and PET suggest that acupuncture-like processes and specific needling can modulate limbic structures such as the anterior cingulate gyrus, insula, and amygdala.33, 34 These structures are known to process cognition and emotions such as anger and fear. It is plausible that the practice of acupuncture influences the patients’ psychological distress related to cancer and cancer therapies, thereby decreasing patient-perceived fatigue. Such psychological improvements should not be discounted as placebo, because they may have a positive therapeutic effect on resilience in the setting of having cancer and receiving intense conventional treatments such as RT. Research is needed to elucidate the mechanism of RT-fatigue. Because acupuncture causes endogenous modulation, it has the potential to both address RT-related fatigue and increase our understanding of the biological basis of RT-related fatigue.

In summary, to our knowledge, we have conducted the first clinical trial of acupuncture to prevent RT-related fatigue and demonstrated its feasibility. The results should be interpreted as feasibility rather than clear evidence that acupuncture is effective for RT-related fatigue. This study highlights that a multidisciplinary approach is needed to conduct a rigorous trial of acupuncture for symptom palliation in the setting of oncology. Effective staffing and recruitment plans should be in place to ensure successful execution, and particular attention must be paid to minority recruitment. Additional research is still needed to explore the biological basis of fatigue. The use of acupuncture in this setting, along with objective measures, may serve as an important tool in translational research that both explores the biological basis of RT-fatigue and elucidates the mechanism of acupuncture as a treatment for this clinical problem.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Mao was supported in part through the NIH/NCCAM 5T32AT000600 grant and is currently supported by NCCAM 1K23AT004112-01A2. The grant agency played no role in the study design or conduct. We thank the cancer patients for their participation in the research and the radiation oncology physicians and clinical staff for their assistance.

References

- 1.Ryan JL, Carroll JK, Ryan EP, Mustian KM, Fiscella K, Morrow GR. Mechanisms of cancer-related fatigue. Oncologist. 2007;12(Suppl 1):22–34. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-S1-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hickok JT, Roscoe JA, Morrow GR, Mustian K, Okunieff P, Bole CW. Frequency, severity, clinical course, and correlates of fatigue in 372 patients during 5 weeks of radiotherapy for cancer. Cancer. 2005 Oct 15;104(8):1772–1778. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jereczek-Fossa BA, Marsiglia HR, Orecchia R. Radiotherapy-related fatigue. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002 Mar;41(3):317–325. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mock V. Evidence-based treatment for cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;(32):112–118. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2000 Feb;18(4):743–753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson T, Mock V. Exercise as an intervention for cancer-related fatigue. Phys Ther. 2004 Aug;84(8):736–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vistad I, Fossa SD, Kristensen GB, Dahl AA. Chronic fatigue and its correlates in long-term survivors of cervical cancer treated with radiotherapy. Bjog. 2007 Sep;114(9):1150–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barsevick AM, Dudley W, Beck S, Sweeney C, Whitmer K, Nail L. A randomized clinical trial of energy conservation for patients with cancer-related fatigue. Cancer. 2004 Mar 15;100(6):1302–1310. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Windsor PM, Nicol KF, Potter J. A randomized, controlled trial of aerobic exercise for treatment-related fatigue in men receiving radical external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2004 Aug 1;101(3):550–557. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mock V, Frangakis C, Davidson NE, et al. Exercise manages fatigue during breast cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2005 Jun;14(6):464–477. doi: 10.1002/pon.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moadel AB, Shah C, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of yoga among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer patients: effects on quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Oct 1;25(28):4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002 Nov-Dec;15(6):463–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh BB, Wu WS, Hwang SH, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Altern Ther Health Med. 2006 Mar-Apr;12(2):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin DP, Sletten CD, Williams BA, Berger IH. Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006 Jun;81(6):749–757. doi: 10.4065/81.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston MF, Xiao B, Hui KK. Acupuncture and fatigue: current basis for shared communication between breast cancer survivors and providers. J Cancer Surviv. 2007 Dec;1(4):306–312. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vickers AJ, Straus DJ, Fearon B, Cassileth BR. Acupuncture for postchemotherapy fatigue: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2004 May 1;22(9):1731–1735. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molassiotis A, Sylt P, Diggins H. The management of cancer-related fatigue after chemotherapy with acupuncture and acupressure: A randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2007 Dec;15(4):228–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sood A, Barton DL, Bauer BA, Loprinzi CL. A critical review of complementary therapies for cancer-related fatigue. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007 Mar;6(1):8–13. doi: 10.1177/1534735406298143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes PM, Power-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Advanced data from vital and health statistics; no343. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2004. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lafferty WE, Bellas A, Corage Baden A, Tyree PT, Standish LJ, Patterson R. The use of complementary and alternative medical providers by insured cancer patients in Washington State. Cancer. 2004 Apr 1;100(7):1522–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertens AC, Sencer S, Myers CD, et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008 Jan;50(1):90–97. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Xie SX, Bowman MA, Armstrong K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and prayer among a national sample of cancer survivors compared to other populations without cancer. Complement Ther Med. 2007 Mar;15(1):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haake M, Muller HH, Schade-Brittinger C, et al. German Acupuncture Trials (GERAC) for Chronic Low Back Pain: Randomized, Multicenter, Blinded, Parallel-Group Trial With 3 Groups. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Sep 24;167(17):1892–1898. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.17.1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mao JJ, Farrar JT, Armstrong K, Donahue A, Ngo J, Bowman MA. De qi: Chinese acupuncture patients’ experiences and beliefs regarding acupuncture needling sensation - an exploratory survey. Acupunct Med. 2007 Dec;25(4):158–165. doi: 10.1136/aim.25.4.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KA, Hicks G, Nino-Murcia G. Validity and reliability of a scale to assess fatigue. Psychiatry Res. 1991 Mar;36(3):291–298. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90027-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meek PM, Nail LM, Barsevick A, et al. Psychometric testing of fatigue instruments for use with cancer patients. Nurs Res. 2000 Jul-Aug;49(4):181–190. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr., LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole RM. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001 Nov;94(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008 Feb;9(2):105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Nov;10(8 Suppl):S13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruner DW, Jones M, Buchanan D, Russo J. Reducing cancer disparities for minorities: a multidisciplinary research agenda to improve patient access to health systems, clinical trials, and effective cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006 May 10;24(14):2209–2215. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SH, Chung SH, Lee JS, et al. Effects of acupuncture on the 5-hydroxytryptamine synthesis and tryptophan hydroxylase expression in the dorsal raphe of exercised rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002 Oct 25;332(1):17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00900-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yonehara N. Influence of serotonin receptor antagonists on substance P and serotonin release evoked by tooth pulp stimulation with electro-acupuncture in the trigeminal nucleus cudalis of the rabbit. Neurosci Res. 2001 May;40(1):45–51. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieboer P, Buijs C, Rodenhuis S, et al. Fatigue and relating factors in high-risk breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant standard or high-dose chemotherapy: a longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2005 Nov 20;23(33):8296–8304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pariente J, White P, Frackowiak RS, Lewith G. Expectancy and belief modulate the neuronal substrates of pain treated by acupuncture. Neuroimage. 2005 May 1;25(4):1161–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]