Abstract

Hydra regenerate throughout their life. We previously described early modulations in cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) DNA-binding activity during regeneration. We now show that the Ser-67 residue located in the P-box is a target for post-translational regulation. The antihydra CREB antiserum detected CREB-positive nuclei distributed in endoderm and ectoderm, whereas the phosphoSer133-CREB antibody detected phospho-CREB-positive nuclei exclusively in endodermal cells. During early regeneration, we observed a dramatic increase in the number of phospho-CREB-positive nuclei in head-regenerating tips, exceeding 80% of the endodermal cells. We identified among CREB-binding kinases the p80 kinase, which showed an enhanced activity and a hyperphosphorylated status during head but not foot regeneration. According to biochemical and immunological evidence, this p80 kinase belongs to the Ribosomal protein S6 kinase family. Exposure to the U0126 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor inhibited head but not foot regeneration, abolished CREB phosphorylation and activation of the early gene HyBra1 in head-regenerating tips. These data support a role for the mitogen-activated protein kinase/ribosomal protein S6 kinase/CREB pathway in hydra head organizer activity.

Species that display regenerative capacities can be found in most animal phyla, from invertebrates to vertebrates, likely representing an ancestral feature lost several times during evolution. The central issue concerning regeneration is the unfolding of developmental programs in adult tissues, ending ultimately in a de novo morphogenesis. That issue is poorly understood, but some stages might rely on conserved ancestral mechanisms. Hydra, which belong to the Cnidaria phylum, a sister group to bilaterians, bud and regenerate throughout their life. Hence their developmental programs stay permanently accessible. Hydra are made up of two cell layers, ectoderm and endoderm, separated by the mesoglea. After midgastric section, regeneration of the missing part is achieved within 3 days, resulting from differentiation of cells from the gastric region in the absence of cell proliferation during the first day.

Although early modulations in gene expression have been identified during regeneration (see ref. 1), little is known about the signaling mechanisms that control regeneration (2, 3). Diacylglycerol treatment induces formation of multiple heads (4), whereas inhibition of PKC and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways selectively block head regeneration and initiation of budding (5–7). In hydra, conserved regulatory elements have been tested in gel retardation assays, and a significant modulation during both apical and basal regeneration was detected with the cAMP response element (CRE). The hydra CRE-binding protein (CREB) gene was cloned, showing a high level of similarity with vertebrate cognate genes (8, 9). In vertebrates, CREB mediates the response to a large array of extracellular signals to the nucleus through posttranslational modifications that involve multiple protein kinases (9, 10), which all phosphorylate CREB and CRE modulator (CREM) at a particular residue, Ser-133 and –117, respectively. This event is critical for modulating CREB activity, because phosphoCREB specifically binds to the transcriptional coactivator CREB-binding protein (11). In this work, we investigated CREB phosphorylation during hydra regeneration and recorded a dramatic increase in the number of phospho-CREB (P-CREB)-expressing cells in head regenerating tips, at the time organizer activity is rising. We also show that a p80 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (RSK) kinase characterized among CREB-binding proteins is involved in this regulation.

Methods

Culture of Animals and Regeneration Experiments. Hydra vulgaris (Hv), Hydra oligactis (Ho), and Hydra viridissima (Cv) were cultured as in ref. 10. Hydra were bisected at midgastric position after 4 days of starvation and kept at 19°C in a 0.5 ml per hydra unless specified. For U0126 treatments, budless animals were pretreated for 90 min, bisected, and left to regenerate in the same medium.

Nuclear Extracts (NE), Whole-Cell Extracts (WCE), and Kinase Assays. NE were prepared as described in ref. 10 with minor modifications; WCE and kinase assays were conducted according to ref. 12 (see Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Immunofluorescence. Hydra were relaxed in 2% urethane, fixed in Lavdowsky fixative for 60 min, stepwise soaked in 10–50% sucrose, and embedded in Tissue-Tek (Sakura, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands). Immunodetection was performed on 10-μm cryosections with hyCREB24 12,000 (8) and phosphoSer133-CREB 1/1,000 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) antibodies.

Immunoprecipitation (IP). For IP coupled to kinase assays, protein A Sepharose beads were incubated in the presence of hyCREB24 antiserum (1/1,000) and washed in 50 mM NaPhosphate, pH 8/300 mM NaCl. WCE (25 μg) were added and incubated for 60 min at 4°C. The IP products were then processed for solid-phase kinase assay (SPKA). For IP coupled to immunodetection, NE and WCE were immunoprecipitated with the hyCREB24 antiserum (1/100) as in ref. 13 and tested in Western analysis with the biotinylated panRSK antibody (1/500, Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY).

mRNA in Situ Hybridization. mRNA in situ hybridization was performed according to ref. 14.

Results

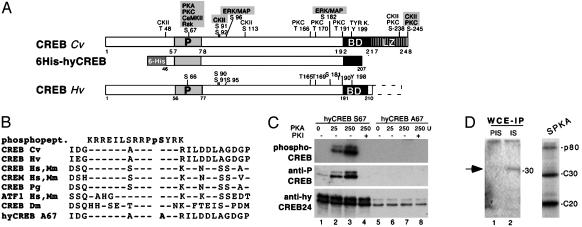

The Hydra CREB Protein Is a Phosphoprotein. The hydra CREB protein characterized from two hydra species (8) exhibits high levels of similarity in the DNA-binding and dimerization domains and also in the kinase inducible domain or P-box (Fig. 1 A and B), a target site for PKA, PKC, CamKII, RSK, and extracellular response kinase/MAPK (9). To verify that the hydra P-box is also a target site for posttranslational regulation, we mutated the Ser-67 residue to Ala (Fig. 1B), and treated with PKA the WT hyCREB-S67 and the mutated hyCREB-A67 proteins. We recorded a PKA dose-dependent phosphorylation level of hyCREB-S67, which was abolished in the presence of PKA inhibitor, whereas no phosphorylation at all was observed with hyCREB-A67 (Fig. 1C Top). When tested in Western analysis, the phosphorylated hyCREB-S67 was recognized by the phosphoSer133-CREB antibody (anti-P-CREB, Fig. 1C), an antibody raised against the rat CREB phosphorylated P-box (Fig. 1B), which detects exclusively the CREB phosphoform (15). As expected, hyCREB-A67 submitted to PKA treatment was not recognized by the antiP-CREB antibody (Fig. 1C). We previously raised two antisera against hyCREB (hyCREB24 and -06), which detected three distinct isoforms migrating as 32-, 31-, and 30-kDa bands (8). The signal intensity obtained with the hyCREB24 antibody was not modified by PKA treatment (Fig. 1C), suggesting this antibody detected predominantly the unphosphorylated form of CREB. These results indicate that the Ser-67 residue within the hyCREB P-box is indeed a substrate for Ser/Thr kinases, including PKA (Fig. 1C), bovine PKC, and CaMKII (not shown), and confirm its equivalence to the Ser-133/-117 phosphorylation sites identified in the vertebrate CREB/CREM P-boxes.

Fig. 1.

The hydra CREB protein is a phosphoprotein. (A) Map of the H. viridissima, Hv, and 6HisCREB proteins. The gray boxed sites indicate phosphorylation sites also present in vertebrate CREB/CREM proteins. P, P-box; BD, binding domain; LZ, leucine zipper domain; Cv, H. viridissima. (B) Alignment of the human (Hs), mouse (Mm), songbird (Pg), Drosophila (Dm), and hydra (H. viridissima, Hv, and S67->A67 mut) P-box sequences to the phosphopeptide used to raise the phosphoSer133-CREB antibody (15). (C) In vitro phosphorylation of 6HisCREB S67 (lanes 1–4) and 6HisCREB A67 (lanes 5–8) proteins bound to Ni-agarose beads, treated with PKA in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP, and detected by autoradiography (Top) and Western analysis by using the anti-P-CREB antibody (Middle). The amount of substrate is shown (Bottom) (hyCREB24 antibody). PKI, PKA inhibitor. (D) Hv WCE contain CREB kinase activities. (Left) WCE immunoprecipitated with hyCREB24 and tested in a kinase assay. IS, immune antiserum; PIS, preimmune serum. The arrow indicates a 32-kDa phosphorylated product (lane 2). (Right) Hv WCE purified on 6HisCREB protein submitted to SPKA. Phosphorylated products were detected by autoradiography. C30, C20: full-length and prematurely terminated 6HisCREBfusion proteins.

When WCE were immunoprecipitated with hyCREB24 and tested in a kinase assay in the absence of any additional enzymatic source, a phosphorylated product was detected at the 32-kDa size (Fig. 1D, lane 2), indicating that products coimmunoprecipitated with the native hydra CREB protein contain CREB kinases. The hyCREB24 and anti-6His antibodies detected the recombinant 6HisCREB protein as 30- and 20-kDa products, corresponding to the full length and prematurely terminated 6HisCREB translation products respectively (not shown). Both of them were efficiently phosphorylated in the presence of WCE purified on 6HisCREB beads (C30 and C20 in Fig. 1D), confirming thus the presence of active CREB kinases. Moreover, in the same assay, an additional phosphoprotein (p80) was detected, which was recognized by neither the hyCREB24, the antiP-CREB, nor the anti-6His antibodies (not shown).

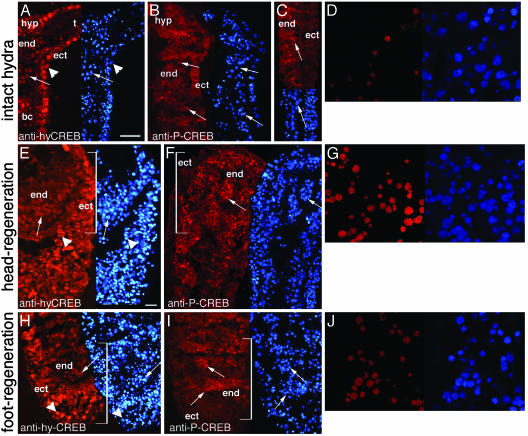

P-CREB-Positive Nuclei Are Restricted to the Endodermal Layer and Are Abundant in Regenerating Stumps. To map CREB- and P-CREB-expressing cells in hydra, we performed comparative immunofluorescence (IF) analyses with the hyCREB24 and the P-CREB antibodies on cryosections. The hyCREB24 antibody provided nuclear signals spread along the body column in both the endodermal (arrows) and ectodermal (arrowheads) cell layers (Fig. 2 A, E, and H). A perfect match between 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained nuclei and CREB IF was noted, thus proving the expected nuclear localization of the CREB transcription factor. In the adult polyp, scattered P-CREB-positive cells were observed in the endodermal layer from the hypostome (region surrounding the mouth) to the basal disk (Fig. 2 B–D) but surprisingly none in the ectodermal one. During regeneration, the number of endodermal P-CREB-positive nuclei clearly increased in both head- and foot-regenerating stumps (Fig. 2 F, G, I, and J), with a maximal density in the former ones, gradually decreasing toward the basal extremity (Fig. 2F). The average number of P-CREB-positive nuclei per 100 endodermal cells was 35 ± 7.4% in the adult body column, 59 ± 7.8% in foot-regenerating stumps, and 83 ± 7% in head-regenerating stumps (see Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). However, similarly to the adult pattern, we detected CREB but no P-CREB signal in the ectodermal layer during regeneration (Fig. 2 E, H).

Fig. 2.

Immunodetection of CREB- and P-CREB-expressing cells in hydra (Hv). The hyCREB24 (A, E, and H) and anti-P-CREB (B–D, F, G, I, J) antibodies were used in intact hydra (A–D), head-(E–G), and foot-(H–J) regenerating halves 4 h after midgastric section. Nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining (blue). Arrowheads: ectodermal positive nuclei; arrows: endodermal positive nuclei; end, endodermal cells; ect, ectodermal cells; hyp, hypostome; t, tentacles; brackets, stump area. (D, G, and J) P-CREB-positive nuclei in confocal views. (Bars = 100 μm in A–C, 40 μm in E, F, H, and I.)

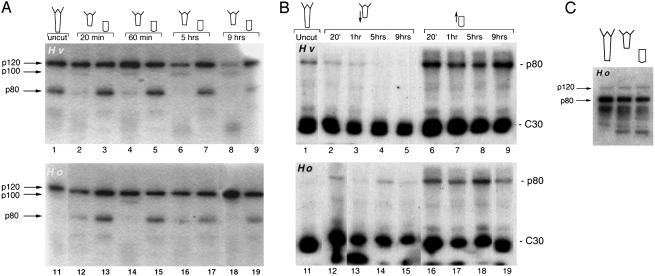

CREB-Binding Kinase Activities Display Specific Temporal Regulation During Regeneration. To identify the kinase(s) supporting this CREB posttranslational regulation in hydra, we performed two distinct kinase assays (12): WCE prepared at various time points after midgastric section were purified on 6HisCREB-loaded beads and assayed in gel kinase assay (GKA, Fig. 3A) and SPKA (Fig. 3B). Within the first hours after bisection, GKA detected three different CREB-binding kinase activities displaying a regeneration-specific regulation, specific for either head or foot regeneration. A p80 kinase showed a high activity level during head regeneration but a drastically reduced one during foot regeneration (Fig. 3A); a p100 kinase displayed low activity levels in foot-regenerating extracts (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) but no activity in Hv head-regenerating extracts. In H. oligactis, a species deficient for foot regeneration (16), the p100 kinase activity was only briefly detected in extracts prepared from upper halves 60 min after bisection (lane 14), being undetectable at other time points, suggesting that p100 kinase activity is linked to foot regeneration. Finally, we observed a p120 kinase activity that was stable or slightly enhanced during head regeneration but lowered during foot regeneration in Hv. This decrease was not observed in H. oligactis upper halves. These kinase activities were not detected when WCE were purified on beads in the absence of the CREB protein (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Temporal regulation of CREB-binding kinases during regeneration. (A) CREB-binding proteins were purified from WCE prepared at indicated time points from either head- (lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 13, 15, 17, and 19) or foot- (lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 16, and 18) regenerating halves and subsequently tested in GKA. Ho, H. oligactis. (B) The extracts used in A were assayed in SPKA to evaluate the modulations in p80 and CREB (C30) phosphorylation levels. (C) GKA showing similar levels in CREB-binding kinase activities in WCE prepared from nonregenerating halves obtained from frozen hydra.

When the same extracts were analyzed in SPKA (Fig. 3B), the 6HisCREB C30 phosphorylation levels were lower in upper halves (compare lanes 2–5 with 6–9). As previously mentioned, an additional p80 phosphorylated product was detected in this assay. This p80 band exhibited low or undetectable phosphorylation levels during foot regeneration but very high levels during head regeneration in Hv and H. oligactis (lanes 6–9 and 16–19). Because in both types of kinase assays a p80 band showed a similar regeneration-specific regulation, we postulated that this 80-kDa phosphorylated product detected in SPKA corresponded to the p80 kinase detected in GKA. To verify that these modulations were linked to regeneration, we prepared extracts from upper and lower halves in the absence of regeneration: hydra were first deep-frozen in nitrogen and immediately bisected. In these conditions, the p80 and p120 kinases displayed similar activities in extracts prepared from upper and lower halves (Fig. 3C), indicating that the observed differences in kinase activities noted in head- and foot-regenerating halves were likely induced on regeneration.

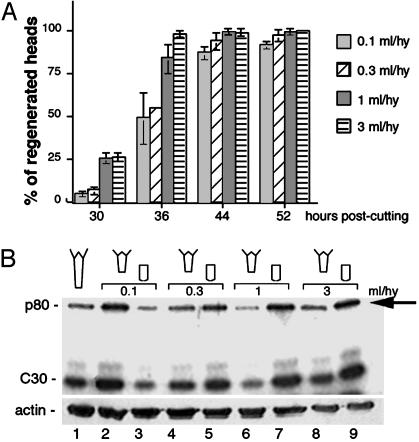

p80 and CREB Phosphorylation Levels Are Modulated by Factors Released on Bisection. Animal density is known to affect regeneration kinetics, and indeed we recorded a significant delay in head and foot regeneration up to 40 h after midgastric section, when animals were kept in small volumes (0.1 and 0.3 ml per hydra) compared to those placed in larger volumes (Fig. 4A and not shown). Hence the substances released on amputation likely negatively affect the regeneration process when present at high concentration. To test their effect on p80 and CREB phosphorylation levels, we carried out similar regeneration experiments where hydra were bisected in volumes varying from 0.1 to 3 ml per hydra, extracts were prepared 60 min after bisection and tested in SPKA (Fig. 4B). In the 0.1 ml per hydra condition, the p80 and CREB phosphorylation levels were high in foot-regenerating extracts but low in head-regenerating ones, whereas the opposite was observed in every other condition, where hydra were allowed to regenerate in a larger volume (compare lanes 2 and 3 with 4–9). Thus, a 3× dilution factor was sufficient to dramatically alter the kinase response in the two stumps. At the 1 ml per hydra dilution (lanes 6 and 7), the difference was maximal; the lowest levels in p80 and CREB phosphorylation were noted in foot-regenerating extracts and the highest ones in head-regenerating extracts. These data prove that substances released on bisection significantly affect the p80 kinase activity although differently in head- and foot-regenerating halves.

Fig. 4.

The hydra factors released on bisection modulate regeneration kinetics and p80 kinase activity. (A) Head regeneration in hydra (Hv) bisected in different volumes and left in the same medium for 3 days. We scored the emergence of tentacle rudiments at indicated time points. Triplicates of 30 hydra were tested in each condition. (B) Kinase assay (SPKA) testing Hv CREB-binding proteins purified from 40 hydra allowed to regenerate for 1 h in indicated volumes. (Upper) The p80 (arrow) and CREB (C30) display parallel phosphorylation variations according to the hydra density. (Lower) Control Western analysis [anti-actin, Abcam (Cambridge, U.K.), 1/5,000].

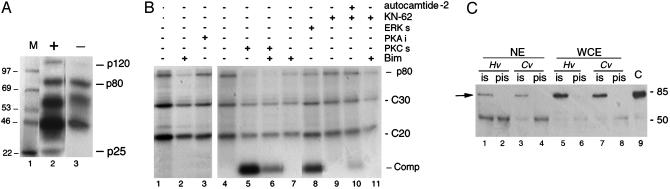

Characterization of the p80 CREB-Binding Kinase. To characterize the p80 kinase, we tested different substrates in GKA. Surprisingly, very similar levels of p80 kinase activity were observed in the presence of 6His-hyCREB, myelin basic protein, or no substrate at all (Fig. 5A and not shown). The latter condition indicates that the p80 kinase has the capacity to autophosphorylate. We then performed SPKA in the presence of inhibitors or competitors for various kinases (Fig. 5B and Fig. 8, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The addition of PKC substrate (PKCs) as competitor and PKC inhibitor (Bim) drastically reduced the phosphorylation levels of both p80 and CREB, although to a lesser extent concerning CREB (lanes 2, 5–7, 11). The PKA inhibitor, which slightly affected the CREB phosphorylation level, did not alter the p80 phosphorylation level (Fig. 5B, lanes 1, 3). In the presence of the extracellular response kinase (ERK)/MAPK competitor (ERKs), p80 phosphorylation level was decreased but not that of CREB (lanes 4 and 8). Finally, the CaMKII competitor (autocamtide-2) or inhibitor (KN-62) did not affect CREB and p80 phosphorylation levels in this assay. These results suggest that the observed modulations in p80 phosphorylation levels rely on PKC-like activity. However, even when the p80 kinase phosphorylation was abolished (Fig. 5B, lanes 5, 6), 6HisCREB remained phosphorylated at a detectable level, proving that additional kinases were present and efficient among CREB-binding proteins, including PKA.

Fig. 5.

Biochemical and immunological characterization of the p80 CREB kinase. (A) GKA showing similar levels in p80 kinase activity in the presence (+, lane 2) or absence (–, lane 3) of substrate in the gel. M, marker. (B) SPKA showing the p80 and 6HisCREB phosphorylation levels when CREB-binding proteins were treated with inhibitors for PKC (Bim 3 μM, lanes 2, 6, 7, and 11), PKA (PKA inhibitor, 9 units, Biolabs, lane 3), CaMKII (KN-62 4 μM, lanes 9–11), and/or competitors for PKC/RSK (Ser-25 peptide 19–31, 0.42 mM, lanes 5, 6), extracellular response kinase (ERK)/MAP kinases (APRTPGRR, 0.69 mM, lane 8), and CaMKII (autocamtide-2 0.44 mM, lane 10), 63×, 100×, and 64× in excess to 6HisCREB, respectively. Lanes 1 and 4, untreated controls for lanes 2, 3, and 5–11, respectively. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of the p80 kinase from Hv (lanes 1, 2, 5, and 6) and H. viridissima (lanes 3, 4, 7, and 8). WCE or NE immunoprecipitated with the anti-hyCREB24 antibody(ies) were analyzed with the biotinylated-panRSK antibody in Western blot. A specific p80 band was detected (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7, arrow). Pis, preimmune serum; C, A431 cell lysate positive control extract.

Homologous PKC kinase domains are present in two distinct kinase families: the PKC and the RSK kinases (17). Therefore, we performed immunological analyses on NE purified on 6His-CREB-loaded beads to further identify the hydra p80 CREB kinase. In Western analyses, the anti-cPKC1 antibody (18) failed to detect any specific signal, whereas the pan-antiRSK antibody detected two major bands migrating as 80 and 50 kDa (not shown). After IP of both NE and WCE with the hyCREB24 antiserum, the biotinylated pan-antiRSK antibody detected a p80 band that was absent when the preimmune serum was used (Fig. 5C), implying that a RSK-like kinase coprecipitated with hyCREB. Taken together, the autophosphorylation property, PKC-like activity, and RSK immunoreactivity indicate that the hydra p80 CREB kinase belongs to the RSK family.

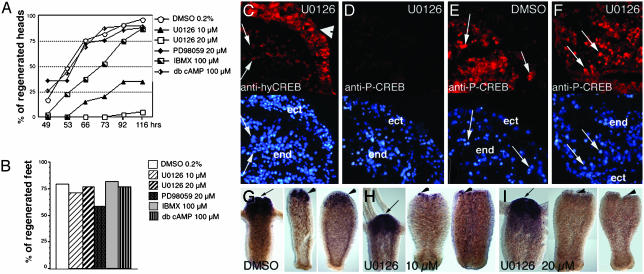

The U0126 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase (MEK) Inhibitor Alters Head but Not Foot Regeneration and Prevents CREB Phosphorylation in Head-Regenerating Stumps. We tested kinase inhibitors on hydra regeneration (Fig. 6) and noted that U0126, a MEK inhibitor that prevents RSK phosphorylation (19), inhibited regeneration in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 6A), whereas foot regeneration was not affected (Fig. 6B): At 10 μM concentration, 35% of the hydra had regenerated tentacles after 5 days; at 20 μM, this value dropped to 3%. Other inhibitors tested in the same assay did not affect head regeneration significantly (Fig. 6A). We then looked for alterations in the P-CREB pattern after U0126 exposure and observed a complete absence of P-CREB-positive nuclei in head-regenerating tips of treated hydra, although CREB was properly expressed (Fig. 6 C and D). In contrast, the P-CREB pattern was not affected in U0126-treated upper halves undergoing foot regeneration and in DMSO-treated control hydra (Fig. 6 E and F). These results suggest that CREB phosphorylation is regulated through distinct signaling cascades in head- and foot-regenerating stumps, the MAPK/RSK pathway being preferentially used during head regeneration. Early regulatory genes up-regulated in head-regenerating tips were proposed to set up the organizer activity that leads to de novo head patterning (3, 20, 21). Interestingly, the HyBra1 early gene (14) expression in U0126-treated hydra was inhibited in head-regenerating tips (Fig. 6 G–I) as a dose-dependent effect but was not affected in adult heads (Fig. 6 G–I) and growing buds (not shown). Thus inhibition of the MAPK pathway dramatically and specifically altered HyBra1 gene activation in head-regenerating hydra.

Fig. 6.

Dose-dependent inhibition of head but not foot regeneration on exposure to the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor U0126. (A) For head regeneration, appearance of tentacle rudiments was recorded on lower halves. (B) For foot regeneration, peroxidase staining (36) was performed on upper halves after 3 days. Forty animals were taken for each condition. (C–F) Immunodetection of either CREB- (C) or P-CREB- (D–F) positive nuclei in regenerating stumps 4 h after bisection exposed to U0126 (20 μM) or DMSO (E Lower)4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. (C–E) Head-regenerating tips. (F) Foot-regenerating tip. Arrows, endodermal positive nuclei; arrowheads, ectodermal positive nuclei. (G–I) HyBra1 whole-mount in situ hybridization performed on 10-h-regenerating upper (Left) and lower halves exposed or not to U0126. Arrows and arrowheads show adult heads and head-regenerating tips, respectively.

Discussion

Conservation of the CREB Pathway in Cnidarians. CREB/CREM proteins have been implicated in a wide variety of physiological and developmental functions in bilaterians (9, 10) and in mouse, CREB inactivation proved its essential function in cell survival during early development (22). In most contexts, CREB activity highly depends on the recruitment of CBP through its phosphorylated P-box (11, 23). Surprisingly the mammalian anti-P-CREB antibody recognized the hydra phosphoSer67-CREB protein, underscoring the functional conservation of the P-box over 700 million years, supported by the recent identification of the CBP gene in cnidarians (V. Schmid and S. Reber, personal communication). In mammals, the RSK kinases respond to neurotransmitters, hormones, and growth factors through the ras-MAPK pathway (24–29). RSK contain two conserved kinase domains, the N-terminal one displaying a PKC-like activity involved in the RSK substrates phosphorylation (17); they autophosphorylate via an intramolecular mechanism (30) and show a regulated nuclear localization (17, 28). In hydra, the p80 CREB-kinase displayed autophosphorylation, PKC-like activity and was recognized as a RSK by immunodetection. Therefore this kinase appears as a putative hydra CREB regulator, at least in head-regenerating stumps where inhibition of RSK phosphorylation blocked regeneration, abolished CREB phosphorylation, and inhibited early induction of gene expression. If confirmed, this would mean that the pathway that couples MAPK to CREB phosphorylation via RSK arose early in evolution. In fact, in hydra, two ras genes have been isolated (31), and activity of a src-related tyrosine kinase, STK, is required for the development of head structures (7). Finally, drugs inhibiting the PKC pathway were shown to block head regeneration (5), hence CREB phosphorylation should also be tested in this context.

That only endodermal cells express the phosphosSer67-CREB form, whereas the CREB protein was detected in both ectodermal and endodermal cell layers, suggests that distinct posttranslational regulations apply in these two cell layers. In vertebrate spermatogenesis, CREM regulation requires neither phosphorylation nor CBP interaction (9).

The CREB Pathway and Organizer Activity in Head-Regenerating Tips. According to our analyses, CREB phosphorylation occurs early in endodermal cells of regenerating stumps, suggesting the activation of some autoregulatory loop. Interestingly, these cells were proposed to support organizer activity at the time reactivation of developmental programs occurs during regeneration (20, 32). Grafting experiments that measure the ability of the grafted regenerating tips to induce a secondary head in the host have shown that, after several hours of postcutting inhibition, head organizer activity is progressively reestablished at the regenerating tip (33). At the gene expression level, some genes are immediately turned on at the wound surface (named “immediate genes”), whereas the “immediate-early” genes start to be expressed within the first 2 hours, most often in endodermal cells of the stump (14, 21, 34, 35). Both immediate and immediate/early genes are detected in head- and foot-regenerating stumps. In many cases, expression of immediateearly genes like Hy-Bra1 (14), cnox-1 (34), Tcf, Wnt (35), and CREB (37) is rapidly extinguished in the foot-regenerating tips but maintained in head-regenerating tips, those genes becoming then early head-specific genes. Thus the asymmetric modulations in CREB phosphorylation and p80/RSK activity observed in time and place where head-specific gene expression is induced might participate in this regulation, as suggested by the U0126-induced inhibition of HyBra1 expression. Interestingly, HyBra1 expression in the adult head was not affected by this treatment, highlighting the difference between the maintenance state of the adult polyp and the dynamic developmental state of the regenerating tip.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Bauer and J. Ritz from the National Center of Competence in Research Bioimaging Platform; S. Hoffmeister (University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany) for providing hydra; U. Technau (Technische Universität Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany) for the HyBra1 probe; and S. Kerridge, P. Sassone-Corsi, and G. Van der Goot for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation (Grant 31-59462), the Canton of Geneva, the Claraz Fonds, the Schmidheiny Foundation, and the Academic Society of Geneva.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: CRE, cAMP-response element; CREB, CRE-binding protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; CREM, CRE modulator; P-CREB, phospho-CREB; NE, nuclear extracts; WCE, whole-cell extracts; IP, immunoprecipitation; GKA, gel kinase assay; SPKA, solid-phase kinase assay; RSK, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; Hv, H. vulgaris.

References

- 1.Galliot, B. (2000) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele, R. (2002) Dev. Biol. 248, 199–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holstein, T., Hobmayer, E. & Technau, U. (2003) Dev. Dyn. 226, 257–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller, W. (1996) Trends Genet. 12, 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardenas, M., Fabila, Y., Yum, S., Cerbon, J., Bohmer, F., Wetzker, R., Fujisawa, T., Bosch, T. & Salgado, L. (2000) Cell Signal. 12, 649–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fabila, Y., Navarro, L., Fujisawa, T., Bode, H. & Salgado, L. (2002) Mech. Dev. 119, 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardenas, M. & Salgado, L. (2003) Dev. Biol. 264, 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galliot, B., Welschof, M., Schuckert, O., Hoffmeister, S. & Schaller, H. (1995) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 121, 1205–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cesare, D., Fimia, G. & Sassone-Corsi, P. (1999) Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaywitz, A. & Greenberg, M. (1999) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 821–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chrivia, J., Kwok, R., Lamb, N., Hagiwara, M., Montminy, M. & Goodman, R. (1993) Nature 365, 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hibi, M., Lin, A., Smeal, T., Minden, A. & Karin, M. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 2135–2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallet, A., Erkner, A., Charroux, B., Fasano, L. & Kerridge, S. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Technau, U. & Bode, H. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 999–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ginty, D., Kornhauser, J., Thompson, M., Bading, H., Mayo, K., Takahashi, J. & Greenberg, M. (1993) Science 260, 238–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmeister, S. (1991) Mech. Dev. 35, 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frodin, M. & Gammeltoft, S. (1999) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 151, 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hassel, M. (1998) Dev. Genes Evol. 207, 489–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Favata, M., Horiuchi, K., Manos, E., Daulerio, A., Stradley, D., Feeser, W., Van Dyk, D., Pitts, W., Earl, R., et al. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18623–18632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galliot, B. & Miller, D. (2000) Trends Genet. 16, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galliot, B. & Schmid, V. (2002) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 46, 39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bleckmann, S., Blendy, J., Rudolph, D., Monaghan, A., Schmid, W. & Schutz, G. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1919–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shikama, N., Lyon, J. & Thangue, N. (1997) Trends Cell Biol. 7, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xing, J., Ginty, D. & Greenberg, M. (1996) Science 273, 959–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pende, M., Fisher, T., Simpson, P., Russell, J., Blenis, J. & Gallo, V. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 1291–1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xing, J., Kornhauser, J., Xia, Z., Thiele, E. & Greenberg, M. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1946–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Cesare, D., Jacquot, S., Hanauer, A. & Sassone-Corsi, P. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 12202–12207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierrat, B., Correia, J., Mary, J., Tomas-Zuber, M. & Lesslauer, W. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29661–29671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberson, E., English, J., Adams, J., Selcher, J., Kondratick, C. & Sweatt, J. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 4337–4348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher, S., Kim, S., Wanner, B. & Walsh, C. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 4732–4740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosch, T., Benitez, E., Gellner, K., Praetzel, G. & Salgado, L. (1995) Gene 167, 191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gauchat, D., Kreger, S., Holstein, T. & Galliot, B. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 1637–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.MacWilliams, H. (1983) Dev. Biol. 96, 239–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gauchat, D., Mazet, F., Berney, C., Schummer, M., Kreger, S., Pawlowski, J. & Galliot, B. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 4493–4498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hobmayer, B., Rentzsch, F., Kuhn, K., Happel, C., Cramer von Laue, C., Snyder, P., Rothbächer, U. & Holstein, T. (2000) Nature 407, 186–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoffmeister, S. & Schaller, H. (1985) Roux Arch. Dev. Biol. 194, 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaloulis, K. (2000) Ph.D. thesis (University of Geneva, Geneva).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.