Abstract

In the lung, Aspergillus fumigatus usually forms a dense colony of filaments embedded in a polymeric extracellular matrix called biofilm (BF). This extracellular matrix embeds and glues hyphae together and protects the fungus from an outside hostile environment. This extracellular matrix is absent in fungal colonies grown under classical liquid shake conditions (PL), which were historically used to understand A. fumigatus pathobiology. Recent works have shown that the fungus in this aerial grown BF-like state exhibits reduced susceptibility to antifungal drugs and undergoes major metabolic changes that are thought to be associated to virulence. These differences in pathological and physiological characteristics between BF and liquid shake conditions suggest that the PL condition is a poor in vitro disease model. In the laboratory, A. fumigatus mycelium embedded by the extracellular matrix can be produced in vitro in aerial condition using an agar-based medium. To provide a global and accurate understanding of A. fumigatus in vitro BF growth, we utilized microarray, RNA-sequencing, and proteomic analysis to compare the global gene and protein expression profiles of A. fumigatus grown under BF and PL conditions. In this review, we will present the different signatures obtained with these three “omics” methods. We will discuss the advantages and limitations of each method and their complementarity.

Keywords: biofilm, transcriptomic, proteomic analysis, RNA-sequencing, RNA-seq, Aspergillus fumigatus

Introduction

During lung infection, Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae are covered by an extracellular matrix (Figures 1A,B) (Loussert et al., 2010). In the case of aspergilloma, hyphae are embedded together in this dense extracellular matrix whereas in invasive aspergillosis hyphae are individually engulfed in the matrix (Figures 1A,B) (Beauvais et al., 2007; Muller et al., 2011). This extracellular matrix protects the fungus against host defense reactions as well as antifungal drugs. The in vivo composition of the mycelial extracellular matrix of A. fumigatus has been reported during host infection (Loussert et al., 2010). The extracellular matrix is composed of polysaccharides, pigment, and proteins. A. fumigatus biofilm (BF) condition can be reproduced in vitro. Indeed, the mycelium growing on porous plastic film deposited on the surface of agar medium plate is able to form an extracellular matrix with a composition closely similar to the in vivo with tightly bound hyphae (Figure 1C) (Beauvais et al., 2007). In contrast, this extracellular matrix is absent in mycelia grown in shake cultures and hyphae are only loosely associated. These differences in organizational and physiological characteristics between the mycelium growing under “planktonic” or “biofilm” condition are associated with specific transcriptional and translational signatures. As the development of the fungal BF in vivo is more close to aerial colony grown on a solid substratum in vitro, it is expected that an analysis of the colony physiology may help to understand the in vivo growth of A. fumigatus in patients.

Figure 1.

Transmission electron microscopy showing the ultrastructure of A. fumigatus biofilm in vivo and in vitro. (A) Invasive aspergillosis in human lung; (B) Aspergilloma in human lung; and (C) 24 h static and aerial culture of A. fumigatus at 30°C. Note the presence of an extracellular material (ECM, arrow) at the surface of the hyphae (H).

High-throughput technologies enable quantitative monitoring of the abundance of various biological molecules and allow quantification of their variation between two different conditions on a genomic scale. Omics approaches involve high-throughput technologies that enable the measurement of global changes in the abundance of mRNA transcripts (transcriptomic), proteins (proteomic), and other biomolecular components (metabolomic) in complex biological systems as a result of chemical perturbation or transition of developmental stages (Nie et al., 2007; Hawkins et al., 2010; Ozsolak and Milos, 2011). Using “omics” methods to compare the mycelium obtained in aerial condition vs. the mycelium growing in submerged condition may allow us to identify the biological process important during the BF growth.

In this review, we will present the different transcriptional and translational signature obtained by using transcriptomic (microarray and RNA-sequencing) and proteomic analyses of BF grown mycelium in comparison to submerged mycelium. In addition, since the application of omics technologies is quite at its infancy in the A. fumigatus field, comparison of these three “omics” methods makes it possible to highlight the advantages and limitations or complementarity of these methods.

Transcriptomic analysis

A. fumigatus ATCC_46645 was the wild-type strain used in these analyses. This genome is composed of 9.926 predicted genes organized in eight chromosomes for a total size of 29.4 Mb (Niermann et al., 2005). Total RNA of aerial colony or submerged mycelium were obtained as described previously (Gibbons et al., 2012).

Data obtained with microarrays and RNA-sequencing analysis

Four biological replicates of the microarray experiment were performed, each time with a reciprocal labeling protocol (“dye-swap”), which served both as a labeling control and technical replicate. The microarrays analysis was realized by using the AF gene chip microarrays that cover about 9600 Open Reading Frames from genome of strain ATCC_46645, sequenced by J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI), The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR). Scanning was performed with an Axon scanner 4000A and the resulting images were analyzed by using GenePix Pro 6.01 software. The Bioplot software was used for statistical analysis. Quantile normalization was applied to the whole data set to account for variation between slides. Expression ratio cutoff of 2.0 and 0.5 were applied to select differentially expressed genes with a p-value <0.05 (Student's t-test). 359 genes differentially expressed in the BF condition as compared to submerged condition were identified. Among them, 193 and 169 genes were up or down regulated, respectively, under the BF growth conditions. The differentially expressed genes were classified according to the functional catalog FunCat. 66.84 and 59.17% of the up and down regulated genes were functionally annotated, which led to the identification of 6 functional categories significantly up regulated and 14 functional categories down regulated in A. fumigatus BF (p < 0.05 Fisher's Exact Test) (Table 1). However, when we considered the percentage of genes up or down regulated per category, this percentage was too low to ascertain the global up or down regulation of any of these functional categories.

Table 1.

Functional categorization of the differentially expressed genes in the biofilm condition by using microarrays.

| Number of hits | Total of hits in the category | % hits of the category | Fisher's exact test p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CATEGORIES UP REGULATED IN BIOFILM BY USING MICROARRAYS | ||||

| Translation | 27 | 214 | 12.6 | 1.05E-13 |

| Ribosome biogenesis | 25 | 255 | 9.8 | 2.75E-10 |

| Fungal/microorganismic cell type differentiation | 21 | 485 | 4.3 | 0.0034 |

| Lipid, fatty acid, and isoprenoid metabolism | 8 | 746 | 1.1 | 0.0168 |

| Protein binding | 45 | 867 | 5.2 | 0.0337 |

| RNA synthesis | 11 | 1511 | 0.7 | 0.0341 |

| CATEGORIES DOWN REGULATED IN BIOFILM BY USING MICROARRAYS | ||||

| Disease, virulence, and defense | 21 | 379 | 5.5 | 1.66E-06 |

| Detoxification | 20 | 407 | 4.9 | 1.89E-05 |

| Respiration | 11 | 155 | 7.1 | 7.34E-05 |

| Fermentation | 8 | 91 | 8.8 | 0.0002 |

| DNA processing | 1 | 578 | 0.2 | 0.0006 |

| Protein binding | 15 | 1511 | 1.0 | 0.0082 |

| Nucleic acid binding | 5 | 754 | 0.7 | 0.0108 |

| Nucleotide/nucleoside/nucleobase metabolism | 1 | 371 | 0.3 | 0.0213 |

| Metabolism of vitamins, cofactors, and prosthetic groups | 11 | 320 | 3.4 | 0.0265 |

| Cell cycle | 5 | 690 | 0.7 | 0.0287 |

| Complex cofactor/cosubstrate/vitamine binding | 14 | 441 | 3.2 | 0.0343 |

| Stress response | 18 | 635 | 2.8 | 0.0357 |

| Secondary metabolism | 16 | 551 | 2.9 | 0.0389 |

| Lipid, fatty acid, and isoprenoid metabolism | 20 | 746 | 2.7 | 0.0499 |

The analysis of the transcriptional signature of the A. fumigatus BF grown under the same conditions was already published by Gibbons et al. (2012) by using RNA-sequencing. This method identified 10-fold more genes differentially expressed in the BF than microarrays. Among the 3729 differentially expressed genes, 2564 genes were up regulated and 1164 genes were down regulated in the BF. The functional categorization of the differentially expressed genes showed a total of 31 up regulated and 31 down regulated functional categories under BF growth conditions (Tables 2, 3). Among the different categories identified, 5 of the 6 up regulated categories and 9 of 14 down regulated categories of the microarrays analysis are retrieved, respectively, among up regulated and down regulated categories identified by using RNA-sequencing (Tables 1, 2, 3). Among the most highly enriched categories of the RNA-sequencing data, the categories linked to transport, detoxification, disease, virulence and defense, and homeostasis were significantly up regulated whereas the categories linked to carbohydrate metabolism such as glycolysis/glucogenesis and tricarboxylic-acid cycle were significantly down regulated.

Table 2.

Functional categorization of the up regulated biofilm genes obtained by using RNA-sequencing.

| Categories up regulated in RNA-sequencing | Number of hits | Total of hits in the category | % hits of the category | Fisher's exact test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport facilities | 286 | 660 | 43.3 | 2.40E-19 |

| Transported compounds (substrates) | 476 | 1328 | 35.8 | 7.33E-13 |

| Regulation of protein activity | 83 | 499 | 16.6 | 7.99E-10 |

| Cell cycle | 128 | 690 | 18.6 | 1.52E-09 |

| DNA processing | 103 | 578 | 17.8 | 2.86E-09 |

| Nucleus | 43 | 304 | 14.1 | 5.55E-09 |

| Nucleic acid binding | 153 | 754 | 20.3 | 2.59E-07 |

| Cellular signaling | 89 | 485 | 18.4 | 3.50E-07 |

| Ribosome biogenesis | 108 | 255 | 42.4 | 4.73E-07 |

| Homeostasis | 118 | 286 | 41.3 | 6.88E-07 |

| Protein binding | 349 | 867 | 40.3 | 7.35E-07 |

| RNA synthesis | 184 | 1511 | 12.2 | 9.77E-07 |

| Detoxification | 154 | 407 | 37.8 | 7.32E-06 |

| Regulation by | 45 | 263 | 17.1 | 3.11E-05 |

| Nucleotide/nucleoside/nucleobase binding | 178 | 796 | 22.4 | 0.0001 |

| Cytoskeleton/structural proteins | 50 | 276 | 18.1 | 0.0001 |

| Transport routes | 352 | 1094 | 32.2 | 0.0006 |

| Lipid, fatty acid, and isoprenoid metabolism | 247 | 746 | 33.1 | 0.0010 |

| Aminoacyl-tRNA-synthetases | 3 | 44 | 6.8 | 0.0010 |

| Mitochondrion | 25 | 151 | 16.6 | 0.0012 |

| Bud/growth tip | 1 | 29 | 3.4 | 0.0014 |

| Translation | 81 | 214 | 37.9 | 0.0014 |

| Stress response | 145 | 635 | 22.8 | 0.0023 |

| Cell growth/morphogenesis | 74 | 348 | 21.3 | 0.0037 |

| Transmembrane signal transduction | 34 | 171 | 19.9 | 0.0155 |

| RNA processing | 98 | 425 | 23.1 | 0.0184 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 21 | 115 | 18.3 | 0.0205 |

| Disease, virulence, and defense | 126 | 379 | 33.2 | 0.0208 |

| Phosphate metabolism | 139 | 575 | 24.2 | 0.0350 |

| Structural protein binding | 9 | 58 | 15.5 | 0.0385 |

| Metabolism of vitamins, cofactors, and prosthetic groups | 74 | 320 | 23.1 | 0.0470 |

Table 3.

Functional categorization of the down regulated biofilm genes obtained by RNA-sequencing.

| Categories down regulated in RNA-sequencing | Number of hits | Total of hits in the category | % hits of the category | Fisher's exact test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport facilities | 32 | 660 | 4.8 | 6.81E-12 |

| Ribosome biogenesis | 6 | 255 | 2.4 | 8.17E-09 |

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 37 | 115 | 32.2 | 1.58E-08 |

| Transported compounds (substrates) | 116 | 1328 | 8.7 | 2.35E-06 |

| Nucleus | 62 | 304 | 20.4 | 4.84E-05 |

| Stress response | 111 | 635 | 17.5 | 7.11E-05 |

| RNA synthesis | 140 | 1511 | 9.3 | 0.0004 |

| Regulation of protein activity | 87 | 499 | 17.4 | 0.0006 |

| Disease, virulence, and defense | 28 | 379 | 7.4 | 0.0016 |

| Bud/growth tip | 10 | 29 | 34.5 | 0.0018 |

| Fermentation | 22 | 91 | 24.2 | 0.0018 |

| Complex cofactor/cosubstrate/vitamine binding | 76 | 441 | 17.2 | 0.0020 |

| C-compound and carbohydrate metabolism | 200 | 1346 | 14.9 | 0.0021 |

| Tricarboxylic-acid pathway (citrate cycle, Krebs cycle, and TCA cycle) | 15 | 53 | 28.3 | 0.0023 |

| Translation | 13 | 214 | 6.1 | 0.0029 |

| Transport routes | 107 | 1094 | 9.8 | 0.0036 |

| Protein folding and stabilization | 28 | 132 | 21.2 | 0.0045 |

| Nucleic acid binding | 116 | 754 | 15.4 | 0.0090 |

| Transmembrane signal transduction | 33 | 171 | 19.3 | 0.0090 |

| DNA processing | 92 | 578 | 15.9 | 0.0092 |

| Fungal/microorganismic cell type differentiation | 79 | 485 | 16.3 | 0.0093 |

| Cell growth/morphogenesis | 59 | 348 | 17.0 | 0.0115 |

| Extracellular metabolism | 1 | 56 | 1.8 | 0.0122 |

| Nitrogen, sulfur and selenium metabolism | 47 | 275 | 17.1 | 0.0188 |

| Homeostasis | 23 | 286 | 8.0 | 0.0210 |

| Nucleotide/nucleoside/nucleobase metabolism | 32 | 371 | 8.6 | 0.0223 |

| Respiration | 28 | 155 | 18.1 | 0.0352 |

| Cell cycle | 103 | 690 | 14.9 | 0.0359 |

| Metabolism of energy reserves (e.g., glycogen and trehalose) | 14 | 66 | 21.2 | 0.0373 |

| Anaplerotic reactions | 2 | 3 | 66.7 | 0.0422 |

| Nucleotide/nucleoside/nucleobase binding | 116 | 796 | 14.6 | 0.0485 |

Transcriptomic signature: microarray vs. RNA-sequencing analysis

Whereas the microarray analysis leads to the identification of hundreds of differentially expressed genes, RNA-sequencing allowed the identification of thousands of genes, which were differentially expressed in the BF. For several categories more than 30% of hits constituting a specific FunCat category were differentially expressed in the RNA-sequencing experiment. In constrast, in microarray analyses no more than 12% of the hits belonging to one category were differentially expressed (Tables 2, 3). Thus, RNA-sequencing allows a more robust identification of functional categories that represent the transcriptional signature of the BF growth of A. fumigatus (Tables 2, 3). Several reasons could explain the difference between signatures obtained with these two methods and justify the current replacement of microarrays analysis by RNA-sequencing data.

The development of microarrays enabled for the first time the simultaneous analysis of the expression levels of thousands of known or putative transcripts. However, microarrays provide mRNA expression pattern data based on the high-throughput and semi quantitative analysis of fluorescence signaling intensities (Morozova et al., 2009). However, this technique has limitations. As the technique relies on hybridization, it poses a range of potential problems such as interfering background hybridization levels, cross hybridization, difference in probe hybridization properties, and dye binding variances. This technological bias means that microarrays do not quantify easily and properly the expression pattern of low abundant transcripts since low intensity fluorescence signals are difficult to distinguish numerically and statistically from the background noise (Roy et al., 2011). Conversely, signal saturation can occur at high intensities and limits the ability to compare transcripts that are expressed at very high levels. In comparison, RNA-sequencing offers several major advantages. Firstly, RNA-sequencing allows quantifying gene expression levels precisely without any background by sequencing each transcript independently (Wang et al., 2009). Secondly, RNA-sequencing is very sensitive and can detect a larger dynamic range of gene expression levels in comparison to microarrays, without a lack of sensitivity for genes expressed at very low or very high levels. Furthermore, RNA-sequencing has showed a better reproducibility for both technical and biological replicates. These methodological and technical variations inherent to the methodologies themselves can explain the difference in the number of differentially expressed genes obtained by applying two methods to one experimental set-up.

In spite of these discrepancies, it was observed that among the 193 up regulated genes identified by microarrays, 119 were also up regulated in the RNA-sequencing data (Figure 2A). Among the 169 down regulated genes identified in the microarrays only 56 were shown to be down regulated in the RNA-sequencing analysis (Figure 2B). Thus, ~49% of the differentially expressed genes identified with microarrays were also retrieved in the RNA-sequencing data with a positive correlation of p = 0.82 (Pearson correlation) (Figure 2C). Some of the common differentially expressed genes found in both transcriptomic methods are discussed below (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Identification of the differentially expressed genes common to both transcriptomic methods. (A) Comparison of the up regulated genes obtained with microarray and RNA-sequencing analysis in the biofilm. (B) Comparison of the down regulated genes obtained with microarray and RNA-sequencing analysis in the biofilm. (C) Comparison of the fold change obtained with microarray and RNA-sequencing analysis.

Table 4.

List of differentially expressed genes common to both transcriptomic methods used.

| Accession number | Gene function | Microarray ratios of intensities | Log2 fold change of ratio intensities | RNA-seq ratio of counts | Log2 fold change of counts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFUA_8G00200 | CalO6, putative | 12.39 | 3.63 | 9885.95 | 13.27 |

| AFUA_1G17250 | Conidial hydrophobin RodB | 16.54 | 4.05 | 4118.35 | 12.01 |

| AFUA_6G11850 | Hypothetical protein | 8.61 | 3.11 | 3408.58 | 11.73 |

| AFUA_7G06620 | Related to L-fucose permease, putative | 2.41 | 1.27 | 243.13 | 7.93 |

| AFUA_4G03240 | Cell wall galactomannoprotein Mp1 | 5.6 | 2.49 | 238.51 | 7.90 |

| AFUA_8G00900 | Cell surface antigen spherulin 4, putative | 7.31 | 2.87 | 212.52 | 7.73 |

| AFUA_5G08800 | Hypothetical protein | 8.32 | 3.06 | 155.28 | 7.28 |

| AFUA_3G01500 | Hypothetical protein | 4.89 | 2.29 | 117.44 | 6.88 |

| AFUA_5G13250 | DUF614 domain protein | 9.8 | 3.29 | 98.50 | 6.62 |

| AFUA_1G14560 | Alpha-mannosidase | 3.99 | 2.00 | 84.72 | 6.40 |

| AFUA_1G00990 | Short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family protein | 4.02 | 2.01 | 79.69 | 6.32 |

| AFUA_4G13050 | Hypothetical protein | 3.07 | 1.62 | 77.73 | 6.28 |

| AFUA_4G01350 | Hypothetical protein | 3.97 | 1.99 | 73.93 | 6.21 |

| AFUA_1G10390 | ABC multidrug transporter, putative | 2.06 | 1.04 | 64.23 | 6.01 |

| AFUA_4G03330 | DUF590 domain protein, putative | 3.83 | 1.94 | 47.61 | 5.57 |

| AFUA_1G03350 | Alpha-1,3-glucanase, putative | 3.73 | 1.90 | 44.20 | 5.47 |

| AFUA_7G00420 | Hypothetical protein | 2.79 | 1.48 | 41.86 | 5.39 |

| AFUA_4G07810 | L-serine dehydratase, putative | 4.67 | 2.22 | 38.63 | 5.27 |

| AFUA_4G08370 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.68 | 1.88 | 37.09 | 5.21 |

| AFUA_5G02330 | Major allergen Asp F1 | 36.71 | 5.20 | 34.45 | 5.11 |

| AFUA_6G02220 | MFS toxin efflux pump, putative | 3.64 | 1.86 | 33.48 | 5.07 |

| AFUA_8G00410 | Methionine aminopeptidase, type II, putative | 3.02 | 1.59 | 32.34 | 5.02 |

| AFUA_6G14340 | Related to berberine bridge enzyme [imported] | 8.28 | 3.05 | 31.45 | 4.98 |

| AFUA_1G12560 | Endo-1,4-beta-glucanase, putative | 9.66 | 3.27 | 31.32 | 4.97 |

| AFUA_1G14800 | Hypothetical protein | 2.62 | 1.39 | 30.98 | 4.95 |

| AFUA_2G15200 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.04 | 1.60 | 30.59 | 4.94 |

| AFUA_4G08380 | Hypothetical protein | 8.98 | 3.17 | 27.58 | 4.79 |

| AFUA_2G15290 | DUF636 domain protein | 18.7 | 4.22 | 27.06 | 4.76 |

| AFUA_2G09030 | Secreted dipeptidyl peptidase | 5.67 | 2.50 | 27.02 | 4.76 |

| AFUA_3G03670 | ABC multidrug transporter, putative | 4.38 | 2.13 | 26.18 | 4.71 |

| AFUA_5G13950 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.72 | 1.44 | 25.98 | 4.70 |

| AFUA_1G02290 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 5.28 | 2.40 | 25.11 | 4.65 |

| AFUA_1G06350 | Virulence related protein (Cap20), putative | 3.35 | 1.74 | 25.04 | 4.65 |

| AFUA_1G14430 | Chitin binding protein, putative | 9.66 | 3.27 | 24.90 | 4.64 |

| AFUA_4G09400 | Aspartic-type endopeptidase (AP3), putative | 3 | 1.58 | 23.10 | 4.53 |

| AFUA_2G00500 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.54 | 1.82 | 19.95 | 4.32 |

| AFUA_3G03650 | Acetyltransferase, GNAT family, putative | 7.88 | 2.98 | 19.03 | 4.25 |

| AFUA_3G08610 | DUF124 domain protein | 4.91 | 2.30 | 17.08 | 4.09 |

| AFUA_6G13830 | Oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family | 2.89 | 1.53 | 16.14 | 4.01 |

| AFUA_1G00930 | Hypothetical protein | 2.95 | 1.56 | 15.40 | 3.94 |

| AFUA_4G09390 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.38 | 1.76 | 15.15 | 3.92 |

| AFUA_3G03640 | Siderochrome-iron transporter (MirB), putative | 5.17 | 2.37 | 13.62 | 3.77 |

| AFUA_6G12170 | FKBP-type peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, putative | 3.61 | 1.85 | 11.97 | 3.58 |

| AFUA_7G00250 | Tubulin beta-2 subunit | 5.13 | 2.36 | 11.46 | 3.52 |

| AFUA_3G02010 | Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, putative | 2.57 | 1.36 | 11.46 | 3.52 |

| AFUA_8G06490 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.3 | 1.72 | 11.15 | 3.48 |

| AFUA_5G03780 | L-PSP endoribonuclease family protein | 3.96 | 1.99 | 10.34 | 3.37 |

| AFUA_2G13500 | Hypothetical protein | 3.05 | 1.61 | 9.47 | 3.24 |

| AFUA_1G01160 | Salivary apyrase, putative | 3.22 | 1.69 | 9.15 | 3.19 |

| AFUA_2G16060 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.43 | 1.28 | 8.56 | 3.10 |

| AFUA_2G04080 | GPR/FUN34 family protein | 5.72 | 2.52 | 7.70 | 2.94 |

| AFUA_7G06540 | Low-specificity L-threonine aldolase, putative | 3.15 | 1.66 | 7.19 | 2.85 |

| AFUA_4G09220 | Hypothetical protein | 2.72 | 1.44 | 6.85 | 2.78 |

| AFUA_8G02060 | Glycan biosynthesis protein (PiGL), putative | 2.11 | 1.08 | 6.47 | 2.69 |

| AFUA_3G00340 | Glycosyl hydrolase, putative | 2.86 | 1.52 | 6.11 | 2.61 |

| AFUA_3G12300 | Ribosomal L22e protein family | 2.82 | 1.50 | 5.60 | 2.49 |

| AFUA_4G00200 | F-box domain protein | 2.91 | 1.54 | 5.45 | 2.45 |

| AFUA_2G16070 | Urease accessory protein UreD | 4.84 | 2.28 | 5.34 | 2.42 |

| AFUA_5G06320 | Membrane biogenesis protein (Yop1), putative | 2.1 | 1.07 | 5.30 | 2.41 |

| AFUA_2G15130 | ABC multidrug transporter, putative | 6.9 | 2.79 | 5.03 | 2.33 |

| AFUA_1G03110 | Ribosomal protein L29 | 2.1 | 1.07 | 4.98 | 2.31 |

| AFUA_5G14930 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 3.74 | 1.90 | 4.87 | 2.29 |

| AFUA_6G12660 | 40s ribosomal protein | 3.09 | 1.63 | 4.74 | 2.24 |

| AFUA_8G00960 | Cytochrome P450, putative | 4.29 | 2.10 | 4.43 | 2.15 |

| AFUA_1G15020 | 40s ribosomal protein S5 | 2.88 | 1.53 | 4.13 | 2.05 |

| AFUA_5G03490 | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase | 2.17 | 1.12 | 4.12 | 2.04 |

| AFUA_2G06150 | Disulfide isomerase, putative | 2.34 | 1.23 | 3.90 | 1.96 |

| AFUA_5G00230 | Hypothetical protein | 4.09 | 2.03 | 3.84 | 1.94 |

| AFUA_6G07290 | Endosomal cargo receptor (Erv14), putative | 2.63 | 1.40 | 3.73 | 1.90 |

| AFUA_1G16690 | MFS transporter, putative | 2.06 | 1.04 | 3.73 | 1.90 |

| AFUA_3G06710 | Ubiquitin thiolesterase (OtuB1), putative | 2.28 | 1.19 | 3.61 | 1.85 |

| AFUA_3G11260 | Ubiquitin (UbiC), putative | 2.12 | 1.08 | 3.57 | 1.83 |

| AFUA_3G07890 | Endo alpha-1,4 polygalactosaminidase, putative | 3.47 | 1.79 | 3.54 | 1.82 |

| AFUA_6G04780 | Vacuolar protein sorting 55 superfamily | 2.43 | 1.28 | 3.46 | 1.79 |

| AFUA_5G11850 | Mitochondrial carrier protein (Pet8), putative | 2.12 | 1.08 | 3.39 | 1.76 |

| AFUA_5G05450 | Ribosomal protein S3Ae cytosolic | 2.28 | 1.19 | 3.29 | 1.72 |

| AFUA_6G00680 | Hypothetical protein | 4.11 | 2.04 | 3.26 | 1.71 |

| AFUA_5G02780 | Nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase | 2.61 | 1.38 | 3.24 | 1.70 |

| AFUA_1G04040 | Ubiquitin (UbiA), putative | 2.89 | 1.53 | 3.23 | 1.69 |

| AFUA_1G16030 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.61 | 1.38 | 3.22 | 1.69 |

| AFUA_6G13250 | Ribosomal protein L31e | 2.16 | 1.11 | 3.19 | 1.68 |

| AFUA_2G05150 | Putative cell wall galactomannoprotein Mp2/allergen F17-like | 7.91 | 2.98 | 3.14 | 1.65 |

| AFUA_3G13320 | 40s ribosomal protein S0, putative | 2.6 | 1.38 | 3.13 | 1.64 |

| AFUA_6G03830 | Ribosomal protein L14 | 3.04 | 1.60 | 3.09 | 1.63 |

| AFUA_1G10380 | Nonribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) | 3.63 | 1.86 | 3.09 | 1.63 |

| AFUA_1G04660 | Ribosomal L15 | 2.08 | 1.06 | 3.06 | 1.61 |

| AFUA_4G01290 | Endo-chitosanase, pseudogene | 15.82 | 3.98 | 3.01 | 1.59 |

| AFUA_3G10730 | Ribosomal protein S7e | 2.16 | 1.11 | 3.00 | 1.59 |

| AFUA_5G09400 | Carbonyl reductase, putative | 3.64 | 1.86 | 3.00 | 1.59 |

| AFUA_4G04070 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.06 | 1.04 | 2.96 | 1.57 |

| AFUA_2G14490 | Endoglucanase, putative | 32.7 | 5.03 | 2.90 | 1.54 |

| AFUA_4G13080 | Monosaccharide transporter | 3.91 | 1.97 | 2.88 | 1.53 |

| AFUA_3G05600 | Ribosomal protein L27a | 2.14 | 1.10 | 2.88 | 1.53 |

| AFUA_7G01590 | Cystathionine gamma-synthase | 2.11 | 1.08 | 2.81 | 1.49 |

| AFUA_7G05300 | Hypothetical protein | 3.1 | 1.63 | 2.78 | 1.47 |

| AFUA_1G09510 | GPI anchored protein, putative | 3.55 | 1.83 | 2.76 | 1.46 |

| AFUA_4G00800 | MFS monosaccharide transporter, putative | 7.39 | 2.89 | 2.73 | 1.45 |

| AFUA_5G08030 | Cellulase CelA, putative | 2.23 | 1.16 | 2.69 | 1.43 |

| AFUA_7G04290 | Amino acid permease (Gap1), putative | 3.43 | 1.78 | 2.68 | 1.42 |

| AFUA_5G03010 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 6.64 | 2.73 | 2.66 | 1.41 |

| AFUA_1G11670 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (LSM8) | 2.21 | 1.14 | 2.53 | 1.34 |

| AFUA_4G03760 | Glycine dehydrogenase | 2.79 | 1.48 | 2.51 | 1.33 |

| AFUA_1G11130 | 60s ribosomal protein yl16a | 2.37 | 1.24 | 2.48 | 1.31 |

| AFUA_1G09530 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.24 | 1.16 | 2.48 | 1.31 |

| AFUA_3G06640 | 40s ribosomal protein s27 type | 2.32 | 1.21 | 2.47 | 1.31 |

| AFUA_7G05290 | Cytosolic small ribosomal subunit S15, putative | 2.31 | 1.21 | 2.43 | 1.28 |

| AFUA_4G07300 | Hypothetical protein | 4.85 | 2.28 | 2.42 | 1.27 |

| AFUA_2G02150 | Ribosomal protein S10 | 2.32 | 1.21 | 2.40 | 1.27 |

| AFUA_1G12350 | Extracellular fruiting body protein, putative | 8.63 | 3.11 | 2.39 | 1.26 |

| AFUA_3G06840 | Cytosolic small ribosomal subunit S4, putative | 2.41 | 1.27 | 2.30 | 1.20 |

| AFUA_2G02990 | MYB DNA-binding domain protein | 2.43 | 1.28 | 2.27 | 1.18 |

| AFUA_5G02950 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 2.7 | 1.43 | 2.24 | 1.16 |

| AFUA_7G08240 | Hypothetical protein | 2.03 | 1.02 | 2.17 | 1.12 |

| AFUA_1G08880 | Heavy metal ion transporter, putative | 2.35 | 1.23 | 2.10 | 1.07 |

| AFUA_6G12820 | MAP kinase (FUS3/KSS1), putative | 3.84 | 1.94 | 2.06 | 1.04 |

| AFUA_7G02570 | Heterokaryon incompatibility protein (Het-C) | 3.96 | 1.99 | 2.05 | 1.04 |

| AFUA_1G06770 | Ribosomal protein S26e | 2.98 | 1.58 | 2.03 | 1.02 |

| AFUA_6G06500 | Actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 1A | 2.13 | 1.09 | 2.02 | 1.02 |

| AFUA_5G09750 | Nucleoside transporter, putative | 2.94 | 1.56 | 2.01 | 1.01 |

| AFUA_1G09690 | tRNA liGase | 0.37 | −1.43 | 0.49 | −1.03 |

| AFUA_7G04010 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.44 | −1.18 | 0.49 | −1.03 |

| AFUA_5G01030 | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 0.03 | −5.06 | 0.49 | −1.04 |

| AFUA_2G09510 | Hypothetical protein | 0.17 | −2.56 | 0.48 | −1.05 |

| AFUA_4G11560 | Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein vps13 | 0.45 | −1.15 | 0.48 | −1.05 |

| AFUA_2G11460 | C6 finger domain protein, putative | 0.32 | −1.64 | 0.46 | −1.12 |

| AFUA_6G02280 | Allergen Asp F3 | 0.32 | −1.64 | 0.45 | −1.16 |

| AFUA_2G15430 | L-xylulose reductase | 0.13 | −2.94 | 0.44 | −1.19 |

| AFUA_1G01600 | Deoxyribodipyrimidine photolyase | 0.2 | −2.32 | 0.42 | −1.25 |

| AFUA_7G01800 | AT DNA binding protein, putative | 0.27 | −1.89 | 0.41 | −1.28 |

| AFUA_3G00370 | D-fructose 6-phosphate phosphoketolase | 0.08 | −3.64 | 0.40 | −1.32 |

| AFUA_3G03400 | Siderophore biosynthesis protein, putative | 0.46 | −1.12 | 0.39 | −1.35 |

| AFUA_2G04190 | Hypothetical protein | 0.28 | −1.84 | 0.37 | −1.44 |

| AFUA_2G06270 | Hypothetical protein | 0.38 | −1.40 | 0.35 | −1.53 |

| AFUA_2G13030 | Phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase alpha subunit (PodG) | 0.36 | −1.47 | 0.32 | −1.63 |

| AFUA_5G11190 | Hypothetical protein | 0.14 | −2.84 | 0.32 | −1.64 |

| AFUA_5G10660 | Pentatricopeptide repeat protein | 0.34 | −1.56 | 0.32 | −1.66 |

| AFUA_5G08200 | Hypothetical protein | 0.25 | −2.00 | 0.31 | −1.70 |

| AFUA_2G11840 | Transcriptional corepressor (Cyc8), putative | 0.42 | −1.25 | 0.30 | −1.75 |

| AFUA_3G14590 | Copper amine oxidase | 0.28 | −1.84 | 0.28 | −1.85 |

| AFUA_2G09350 | Endo-beta-1,6-glucanase, putative | 0.37 | −1.43 | 0.27 | −1.88 |

| AFUA_2G05450 | 64 kDa mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase | 0.41 | −1.29 | 0.27 | −1.92 |

| AFUA_4G08170 | Succinate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase | 0.43 | −1.22 | 0.25 | −1.98 |

| AFUA_5G14680 | Hypothetical protein | 0.18 | −2.47 | 0.25 | −2.02 |

| AFUA_8G05380 | Hypothetical protein | 0.48 | −1.06 | 0.22 | −2.21 |

| AFUA_2G01140 | GPI anchored protein, putative | 0.31 | −1.69 | 0.21 | −2.23 |

| AFUA_2G07680 | L-ornithine N5-oxygenase | 0.46 | −1.12 | 0.21 | −2.25 |

| AFUA_3G05780 | GATA transcription factor (LreA), putative | 0.13 | −2.94 | 0.20 | −2.29 |

| AFUA_2G16520 | Phospholipase D (PLD), putative | 0.42 | −1.25 | 0.20 | −2.30 |

| AFUA_6G04920 | NAD-dependent formate dehydrogenase | 0.27 | −1.89 | 0.17 | −2.57 |

| AFUA_8G05600 | Hypothetical protein | 0.07 | −3.84 | 0.16 | −2.64 |

| AFUA_1G13800 | mfs-multidrug-resistance transporter | 0.28 | −1.84 | 0.16 | −2.65 |

| AFUA_5G06240 | Alcohol dehydrogenase. putative | 0.09 | −3.47 | 0.15 | −2.72 |

| AFUA_8G05580 | Coenzyme A transferase PsecoA | 0.19 | −2.40 | 0.15 | −2.76 |

| AFUA_4G08960 | GPI anchored protein, putative | 0.19 | −2.40 | 0.14 | −2.86 |

| AFUA_2G13830 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.41 | −1.29 | 0.13 | −2.95 |

| AFUA_5G07590 | Hypothetical protein | 0.32 | −1.64 | 0.13 | −2.96 |

| AFUA_7G08280 | Hypothetical protein | 0.35 | −1.51 | 0.12 | −3.02 |

| AFUA_2G09220 | Hypothetical protein | 0.31 | −1.69 | 0.12 | −3.04 |

| AFUA_1G03610 | Hypothetical protein | 0.11 | −3.18 | 0.12 | −3.05 |

| AFUA_1G12250 | Mitochondrial hypoxia responsive protein | 0.16 | −2.64 | 0.12 | −3.07 |

| AFUA_1G10610 | Hypothetical protein | 0.27 | −1.89 | 0.11 | −3.16 |

| AFUA_6G13380 | Hypothetical protein | 0.4 | −1.32 | 0.11 | −3.24 |

| AFUA_3G05760 | C6 transcription factor (Fcr1), putative | 0.09 | −3.47 | 0.10 | −3.34 |

| AFUA_4G11720 | Phosphatidyl synthase | 0.12 | −3.06 | 0.10 | −3.39 |

| AFUA_1G12840 | Nitrite reductase | 0.2 | −2.32 | 0.09 | −3.49 |

| AFUA_5G12530 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.42 | −1.25 | 0.08 | −3.68 |

| AFUA_4G03460 | HLH DNA binding domain protein, putative | 0.13 | −2.94 | 0.08 | −3.72 |

| AFUA_3G11070 | Pyruvate decarboxylase PdcA, putative | 0.1 | −3.32 | 0.07 | −3.80 |

| AFUA_3G10750 | Acetate kinase, putative | 0.34 | −1.56 | 0.06 | −4.04 |

| AFUA_4G03410 | Flavohemoprotein | 0.07 | −3.84 | 0.05 | −4.32 |

| AFUA_1G12830 | Nitrate reductase NiaD | 0.14 | −2.84 | 0.05 | −4.40 |

| AFUA_1G15270 | ATP-dependent Clp protease, putative | 0.17 | −2.56 | 0.02 | −5.44 |

| AFUA_3G14540 | 30 kDa heat shock protein | 0.23 | −2.12 | 0.02 | −5.44 |

| AFUA_2G05060 | Alternative oxidase | 0.03 | −5.06 | 0.02 | −5.86 |

| AFUA_5G02700 | Multidrug resistant protein | 0.07 | −3.84 | 0.01 | −6.09 |

A large proportion of common genes up regulated in the BF are involved in the transcriptional and translational regulation reflecting the establishment of different transcriptional and translational programs between these two growth conditions.

Genes coding for antigenic and allergenic proteins are differentially expressed in the BF. Two of the major allergens of A. fumigatus, the ribotoxin Asp F1 and the allergen Asp F7-like (extracellular cellulase CelA) are up regulated in the A. fumigatus BF (Madan et al., 1997a,b; Alvarez-Garcia et al., 2010). Among the 81 allergens identified in A. fumigatus, 39 genes were shown to be up regulated under BF conditions by using RNA-sequencing (Mari and Scala, 2006). Noteworthy, the secreted galactomannoprotein Afmp1p and the mannoprotein Afmp2p are up regulated in the BF (Woo et al., 2002; Chong et al., 2004). Afmp1p and Afmp2p are specific to A. fumigatus and are not found in other Aspergillus species. A clinical evaluation of sera from invasive aspergillosis patients has revealed that they contained circulating Afmp1p proteins as well as antibodies directed against both Afmp1p and Afmp2p proteins. A dual detection system was suggested for the diagnosis of aspergillosis based on the presence of circulating Afmp1 antigen and antibodies against Afmp2p. An overexpression of antigenic molecule does not occur in all cases, e.g., the allergen thioredoxin peroxidase AspF3 is down regulated in the BF (Kniemeyer et al., 2009). The occurrence of a higher production of allergens/antigens in the BF condition is in agreement with the initial observations that growth of the fungus in an infected lung is similar to the in vitro BF growth.

The rodB gene belonging to the hydrophobins family is also highly up regulated in the BF. A. fumigatus has at least six genes that code for hydrophobins, but only rodA and rodB have been studied for virulence implications (Paris et al., 2003). The rodA gene encodes a small hydrophobic cysteine-rich polypeptide present on the surface of the conidia and the deletion mutant displays a conidial cell wall without rodlet layer allowing a better recognition to alveolar macrophages. The rodA mutant produced smaller lung lesions and weaker inflammatory response than the reference wild-type strain in a murine model of invasive aspergillosis. However, although the rodB gene is highly expressed in the BF, the rodB deletion mutant did not show any obvious morphological phenotypes. The role of this hydrophobin in mycelial growth remains obscure.

The gene coding for the putative O-methyltransferase CalO6 is one of the most up regulated gene in the BF found in both analyses. This gene belongs to a secondary metabolism supercluster responsible for the biosynthesis of fumitremorgin, pseurotin A, and an unknown secondary metabolite (Khaldi et al., 2010). Among this supercluster composed of 44 genes, 3 genes were found to be up regulated in the microarray data set in comparison to 32 up regulated genes identified by RNA-sequencing. Fumitremorgin was shown to be an inhibitor of chemotherapy-resistant breast cancer cells and conferred sensitivity to anticancer drugs (Grundmann et al., 2008). In spite of these interesting biological characteristics, the potential role of fumitremorgins in Aspergillus pathogenesis has not been elucidated yet. The role of the pseurotin A toxin in the pathogenesis of A. fumigatus is also poorly understood (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Vodisch et al., 2011). The pseurotin A toxin was shown to be produced under hypoxic conditions and showed a slight cytotoxicity against lung fibroblasts and the capacity to inhibit IgE production (Ishikawa et al., 2009). Most of the studies on Aspergillus fumigatus mycotoxins dealt with gliotoxin. The corresponding gene cluster of gliotoxin is up regulated in the BF (Bruns et al., 2010; Speth et al., 2011; Scharf et al., 2012). Even though their role in fungal pathogenicity was suggested by these studies, their role during infection has not been experimentally assessed using pure substance.

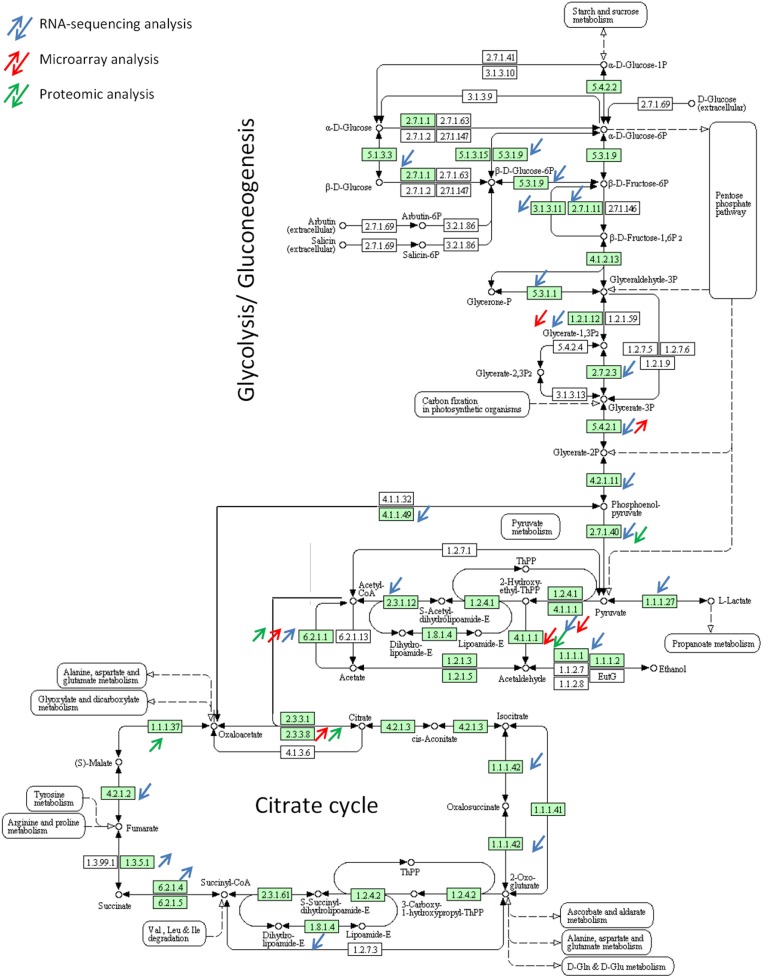

RNA-sequencing as compared to microarrays provides clear evidence that entire pathways are differentially expressed. For example, the glycolysis pathway responsible for the conversion of glucose to pyruvate was shown to be down regulated in the A. fumigatus BF in both transcriptomic methods. Whereas microarrays allowed the identification of only 5 down regulated genes of the glycolysis, the RNA-sequencing highlighted 17 down regulated genes out of 28 genes constituting the glycolysis pathway (Figure 3). Genes encoding enzymes of the tricarboxylic-acid cycle are also differentially expressed as revealed by both transcriptomic methods. Genes encoding enzymes responsible of the conversion of citrate to succinyl-CoA, the oxidative branch of the TCA cycle, were shown to be down regulated in RNA-sequencing whereas enzymes participating in the conversion of succinyl-CoA to oxaloacetate were shown to be up regulated. In line with this, the isocitrate lyase, which is involved in the conversion of isocitrate to glyoxylate and succinate was shown to be up regulated in both analyses. These results reflect that the fungus may not acquire energy by fermentation but by metabolizing acetyl-CoA using the glyoxylate cycle under BF conditions. NADH formed by this cycle can enter then in the respiratory chain pathway. Genes belonging to the mitochondrial complexes II, III, and V, controlling oxidative phosphorylation, were shown to be up regulated in the BF in the RNA-sequencing analysis. In Candida albicans, levels of isocitrate lyase and malate synthase are greatly increased upon contact with its human host and interestingly, isocitrate lyase has been shown to be key virulence factor (Lorenz and Fink, 2001). In contrast, isocitrate lyase of A. fumigatus is not essential for the development of invasive aspergillosis in a murine model (Schobel et al., 2007).

Figure 3.

Differential expression of genes involved in glycolysis pathway and TCA cycle during biofilm growth.

One hundred and forty transporter genes were up regulated in the BF based on RNA-sequencing analysis. In comparison, microarrays revealed only the up regulation of only 5 MFS and 3 ABC transporters. The Mdr4 transporter was shown to be up regulated in an in vivo BF mouse model during voriconazole treatment (Langfelder et al., 2002; Nascimento et al., 2003; Rajendran et al., 2011). The ABC transporters Mdr1, Mdr2, and Mdr4 which are overexpressed in itraconazole-resistant mutants induced in vitro are also up regulated in our BF condition in the RNA-sequencing analysis (Nascimento et al., 2003). Thus, the up regulation of these efflux pumps in A. fumigatus could lead to azole resistance in BF grown A. fumigatus cultures. A recent study showed that the A. fumigatus BF sensitivity to voriconazole was increased in presence of an efflux pump inhibitor reflecting the importance of the transport activity in the BF to counteract the action of inhibitors in association with the 14-α-demethylase Cyp51A (Rajendran et al., 2011).

Proteomics analysis

Large-scale analysis of the proteome is also important for a better understanding of the cellular, metabolic, and regulatory networks in the cell. Proteomic analysis offers the advantage to visualize the final product of the gene transcription. This methodology has still a bias against low-abundance and membrane proteins. However, targeted proteomic approaches based on LC-MS/MS techniques, such as selected reaction monitoring (SRM), have the potenial to detect proteins with low copy numbers (Picotti et al., 2009). In A. fumigatus, around 650 proteins have so far been identified by 2D-gel electrophoresis for a genome that has ~10,000 genes (Teutschbein et al., 2010). The proteomic analysis of the BF condition after 16 h growth as compared to submerged condition was performed as described by Bruns et al. (2010), with slight modifications. 2D-gel images were analyzed by using Delta 2D 4.3 (Decodon, Germany). Analysis of the 2-D gel patterns obtained revealed that 43 spots showed significant changes in abundance between the BF and planktonic cultures (Figure 4). Among them, 25 different proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF-analyses (Table 5). Three proteins were up and 22 were down regulated under BF conditions.

Figure 4.

2D electrophoretic separation of protein extracts of A. fumigatus grown under submerged (PL) and biofilm (BF) culture conditions. In total, 43 different protein spots of A. fumigatus changed significantly their abundance within 16 h of growth (protein spots are labeled with spot numbers as indicated in Table 5). A. fumigatus proteins were labeled with the CyDye DIGE Fluor minimal dye labeling kit. Subsequently, proteins were separated by 2D gel electrophoresis using immobilized pH gradient strips with a pH range of 3–11 NL in the first dimension. For the separation of proteins in the second dimension, SDS-polyacrylamide gradients gels (11–16%) were used. Differentially regulated proteins were identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF analysis. A three color overlaid gel image is shown. Samples were labeled as follows: ATCC 46645-planctonic culture control sample (Cy3), ATCC 46645-biofilm culture sample (Cy5), and internal standard (Cy2).

Table 5.

List of differentially expressed proteins obtained by using proteomic analysis.

| Accession number | Spot numbera | Putative function | Proteomic ratio of biofilm/planctonic conditionsb | RNA-seq ratio of biofilm/planctonic conditionsc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AFUA_1G05340 | 38 | 40s ribosomal protein S19 | 0.43 | 4.21 |

| 2 | AFUA_1G07480 | 15 | Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase | 0.39 | |

| 3 | AFUA_1G12890 | 20 | Probable 60s ribosomal protein l5 | 0.40 | |

| 22 | 0.40 | ||||

| 4 | AFUA_1G14120 | 11 | Nuclear segregation protein (Bfr1) | 0.47 | |

| 5 | AFUA_1G16840 | 32 | TCTP family protein | 0.43 | 2.96 |

| 6 | AFUA_2G04060 | 15 | NADH:flavin Oxidoreductase/NADH oxidase family protein | 0.39 | 0.14 |

| 7 | AFUA_2G07420 | 6 | Actin-bundling protein Sac6 | 0.39 | |

| 8 | AFUA_2G11010 | 9 | Dihydroorotate reductase PyrE | 0.15 | |

| 10 | 0.37 | ||||

| 9 | AFUA_2G11150 | 12 | Secretory pathway gdp dissociation inhibitor | 0.49 | |

| 10 | AFUA_3G00590 | 41 | Asp-hemolysin | 0.36 | |

| 11 | AFUA_3G08420 | 34 | Cystathionine beta-synthase (beta-thionase) | 0.45 | |

| 12 | AFUA_3G12300 | 39 | 60s ribosomal protein L22 | 0.37 | 5.60 |

| 13 | AFUA_4G03410 | 13 | Flavohemoprotein | 0.28 | 0.05 |

| 14 | 0.32 | ||||

| 14 | AFUA_4G08240 | 19 | Zinc-containing alcohol dehydrogenase | 0.47 | 0.05 |

| 15 | AFUA_4G11080 | 40 | Acetyl-coenzyme A synthetase FacA | 2.40 | 0.29 |

| 16 | AFUA_5G02370 | 6 | Vacuolar ATP synthase catalytic subunit A | 0.39 | |

| 17 | AFUA_5G06240 | 18 | Alcohol dehydrogenase, putative | 0.24 | 0.15 |

| 23 | 0.35 | ||||

| 18 | AFUA_5G09910 | 33 | Nitroreductase family protein | 0.38 | 0.12 |

| 19 | AFUA_5G14680 | 29 | Conserved hypothetical protein | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| 30 | 0.32 | ||||

| 31 | 0.14 | ||||

| 20 | AFUA_6G02420 | 43 | Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme (UbcM) | 2.01 | 4.77 |

| 21 | AFUA_6G02750 | 36 | Nascent polypeptide-associated complex (NAC) subunit | 0.42 | 2.09 |

| 22 | AFUA_6G05210 | 27 | Malate dehydrogenase, NAD-dependent | 2.12 | |

| 23 | AFUA_6G07430 | 7 | Pyruvate kinase | 0.45 | 0.43 |

| 24 | AFUA_7G01010 | 19 | Alcohol dehydrogenase | 0.47 | 83.45 |

| 25 | AFUA_8G03930 | 3 | Hsp70 chaperone (HscA) | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| 4 | 0.49 | ||||

| 5 | 0.45 |

Spot number in Figure 4.

Average ratios compared under biofilm and planctonic growth conditions were extracted from statistical analysis of DIGE gels by the Delta2D 4.3 (Decodon) software program. “>2” a consistent increase of greater than twofold. “<2” a consistent decrease of more than twofold.

The transcriptional changes determined by RNA-seq are aligned.

Proteomic vs. RNA-seq data

The comparison of the transcriptomic and proteomic data has revealed that 16 genes corresponding to differentially regulated proteins were retrieved in the RNA-sequencing data vs. only 5 genes for microarrays. Only 8 of the 22 down regulated proteins and corresponding mRNA were found to be down regulated (cutoff <0.5) with a correlation of p = 0.43 (Pearson correlation) and one protein and its corresponding mRNA was up regulated. These results stressed the difficulties in correlating transcriptome and proteome data. Several reasons may explain the low number of differentially expressed proteins and the low degree of correlation between transcriptomic and proteomic analyses (Nie et al., 2007; Sukardi et al., 2010). For technical reasons, the current two-dimensional gel-based analyses focus mainly on the cytoplasmic subset of the cell proteome due to the impossibility to date to extract most membrane or hydrophobic proteins. Proteins are then separated according to their isoelectric point and molecular mass. So proteins with an extreme isoelectric point or molecular mass are not amenable to 2D-gel electrophoresis. A sufficient amount of protein present in one spot is also crucial for the unambiguous identification of the protein by MALDI-TOF/TOF-analyses. Conversely, RNA-sequencing allows the identification of thousand mRNAs differentially regulated between two conditions. However, the transcript levels detected in mRNA profiling do not reflect all the regulatory processes in the cell, such as post-transcriptional-processes occurring before translation, the half-lives of mRNAs and proteins and the post-translational regulation on the protein level as the quality control of proteins and the degradation in the proteasome. Conversely to RNA-sequencing, the proteomic analysis highlights fewer regulated proteins but assured their real up regulation or down regulation in the cell. Thus, even if a limited number of proteins were identified by proteomic analysis, some of them could confirm the up regulation of pathways or genes in the BF at the protein level.

Among the proteins identified, proteins involved in the translational regulation and post-translational modifications are found. The data were in agreement with the transcriptomic data and shows that the transcriptional and translational processes involved in the two growth conditions were different.

Similarly, the pyruvate kinase was down regulated whereas the acetyl-CoA synthetase FacA and the malate dehydrogenase were up regulated in the BF. These results confirmed the down regulation of the glycolysis pathway and the up regulation of final steps of the TCA at the protein level.

The Asp-hemolysin protein was down regulated in the BF. Asp-hemolysin was reported to be released into the culture supernatant by A. fumigatus during growth in presence of elastin, collagen, and keratin, where it is supposed to exhibit a hemolytic activity (Wartenberg et al., 2011). However, the characterization of the deletion strain Δasp-HS did not revealed significant hemolytic and cytotoxic activity and the impact on pathogenicity and the biological role of the Asp-HS protein is still poorly understood.

All proteome data (gel images, spot information) were imported into our in-house data ware-house Omnifung http://www.omnifung.hki-jena.de and are publicly accessible.

Conclusions

In recent years, many high-throughput technologies have been developed to decipher various aspects of cellular processes, including the transcriptome, epigenome, proteome, metabolome, or interactome. The capacity to perform “omics” analyses at several different levels, such as transcriptomic, proteomic, or metabolomics, and their comparison and integration of information offers an exciting potential to answer many questions asked by a biological study. However, even if the utilization of different “omics” methods can be complementary, the combination of the different data obtained remains a challenge. Among the three “omics” methods used to identify the specific signature of the A. fumigatus BF, the RNA-sequencing has exceeded microarrays and is the most powerful analysis giving precise information on the expression of the entire genes of the genome in a biological sample with a few degree of variability. RNA-sequencing has allowed the identification of up regulated genes involved in transport, secondary metabolism, antigenic and allergenic molecules during BF growth. Data obtained have reflected the metabolic reorganization occurring in the BF. Thus, RNA-sequencing allows the identification of the genes differentially expressed between two biological conditions, but it also provides information concerning sequence variations such as alternative splicing events, gene fusion detection, and small RNA characterization at single-nucleotide resolution (Morozova et al., 2009). In contrast, proteomic analysis allows the identification of proteins, the final product of the gene expression, but the information collected is limited due to the high dynamic range of protein concentration within a cell and the difficulties in analyzing membrane proteins. However, the tremendous progress in LC-MS/MS-based proteomics, which has recently been made, opens up the possibility to detect and quantify also low abundant, highly glycosylated, and hydrophobic proteins including membrane proteins (Savas et al., 2011). To date even though these “omics” technologies are very appealing, the data obtained so far have not yet been able to solve the identification of virulence factors in A. fumigatus. Due to the opportunistic pathogenicity of the species, the identification of the essential metabolic pathways under in vivo conditions may be a better option than the search for specific virulence factors. In this option, “omics” technologies have a great future in the field of human-pathogenic fungi.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007-2013] under grant agreement n° HEALTH-2010-260338 (ALLFUN), ERA-Net Pathogenomics Biomarkers for prevention, diagnosis and response to therapy of invasive aspergillosis (AspBIOmics), and ESF (European science Foundation) Fuminomics.

References

- Alvarez-Garcia E., Batanero E., Garcia-Fernandez R., Villalba M., Gavilanes J. G., Martinez-Del-Pozo A. (2010). A deletion variant of the Aspergillus fumigatus ribotoxin Asp f 1 induces an attenuated airway inflammatory response in a mouse model of sensitization. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 20, 69–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais A., Schmidt C., Guadagnini S., Roux P., Perret E., Henry C., et al. (2007). An extracellular matrix glues together the aerial-grown hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 1588–1600 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00895.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns S., Seidler M., Albrecht D., Salvenmoser S., Remme N., Hertweck C., et al. (2010). Functional genomic profiling of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilm reveals enhanced production of the mycotoxin gliotoxin. Proteomics 10, 3097–3107 10.1002/pmic.201000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong K. T., Woo P. C., Lau S. K., Huang Y., Yuen K. Y. (2004). AFMP2 encodes a novel immunogenic protein of the antigenic mannoprotein superfamily in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 2287–2291 10.1128/JCM.42.5.2287-2291.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons J. G., Beauvais A., Beau R., McGary K. L., Latge J. P., Rokas A. (2012). Global transcriptome changes underlying colony growth in the opportunistic human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 11, 68–78 10.1128/EC.05102-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann A., Kuznetsova T., Afiyatullov S., Li S. M. (2008). FtmPT2, an N-prenyltransferase from Aspergillus fumigatus, catalyses the last step in the biosynthesis of fumitremorgin B. Chembiochem 9, 2059–2063 10.1002/cbic.200800240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins R. D., Hon G. C., Ren B. (2010). Next-generation genomics: an integrative approach. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 476–486 10.1038/nrg2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M., Ninomiya T., Akabane H., Kushida N., Tsujiuchi G., Ohyama M., et al. (2009). Pseurotin A and its analogues as inhibitors of immunoglobulin E [correction of immunoglobuline E] production. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 19, 1457–1460 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaldi N., Seifuddin F. T., Turner G., Haft D., Nierman W. C., Wolfe K. H., et al. (2010). SMURF: genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 736–741 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniemeyer O., Lessing F., Brakhage A. A. (2009). Proteome analysis for pathogenicity and new diagnostic markers for Aspergillus fumigatus. Med. Mycol. 47Suppl. 1, S248–S254 10.1080/13693780802169138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder K., Gattung S., Brakhage A. A. (2002). A novel method used to delete a new Aspergillus fumigatus ABC transporter-encoding gene. Curr. Genet. 41, 268–274 10.1007/s00294-002-0313-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz M. C., Fink G. R. (2001). The glyoxylate cycle is required for fungal virulence. Nature 412, 83–86 10.1038/35083594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussert C., Schmitt C., Prevost M. C., Balloy V., Fadel E., Philippe B., et al. (2010). In vivo biofilm composition of Aspergillus fumigatus. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 405–410 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan T., Arora N., Sarma P. U. (1997a). Ribonuclease activity dependent cytotoxicity of Asp fl, a major allergen of A. fumigatus. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 175, 21–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madan T., Banerjee B., Bhatnagar P. K., Shah A., Sarma P. U. (1997b). Identification of 45 kD antigen in immune complexes of patients of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 166, 111–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari A., Scala E. (2006). Allergome: a unifying platform. Arb. Paul Ehrlich Inst. Bundesamt Sera Impfstoffe Frankf. A M 95, 29–39; discussion: 39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozova O., Hirst M., Marra M. A. (2009). Applications of new sequencing technologies for transcriptome analysis. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10, 135–151 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-145957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller F. M., Seidler M., Beauvais A. (2011). Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms in the clinical setting. Med. Mycol. 49Suppl. 1, S96–S100 10.3109/13693786.2010.502190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento A. M., Goldman G. H., Park S., Marras S. A., Delmas G., Oza U., et al. (2003). Multiple resistance mechanisms among Aspergillus fumigatus mutants with high-level resistance to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 1719–1726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L., Wu G., Culley D. E., Scholten J. C., Zhang W. (2007). Integrative analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data: challenges, solutions and applications. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 27, 63–75 10.1080/07388550701334212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niermann W. C., Pain A., Anderson M. J., Wortman J. R., Kim H. S., Arroyo J., et al. (2005). Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Nature 22, 1151–1156 10.1038/nature04332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozsolak F., Milos P. M. (2011). RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 87–98 10.1038/nrg2934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris S., Debeaupuis J. P., Crameri R., Carey M., Charles F., Prevost M. C., et al. (2003). Conidial hydrophobins of Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 1581–1588 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1581-1588.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picotti P., Bodenmiller B., Mueller L. N., Domon B., Aebersold R. (2009). Full dynamic range proteome analysis of S. cerevisiae by targeted proteomics. Cell 21, 795–806 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran R., Mowat E., McCulloch E., Lappin D. F., Jones B., Lang S., et al. (2011). Azole resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus biofilms is partly associated with efflux pump activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 2092–2097 10.1128/AAC.01189-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy N. C., Altermann E., Park Z. A., McNabb W. C. (2011). A comparison of analog and Next-Generation transcriptomic tools for mammalian studies. Brief. Funct. Genomics 10, 135–150 10.1093/bfgp/elr005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savas J. N., Stein B. D., Wu C. C., Yates J. R. (2011). Mass spectrometry accelerates membrane protein analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 388–396 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf D. H., Heinekamp T., Remme N., Hortschansky P., Brakhage A. A., Hertweck C. (2012). Biosynthesis and function of gliotoxin in Aspergillus fumigatus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 467–472 10.1007/s00253-011-3689-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schobel F., Ibrahim-Granet O., Ave P., Latge J. P., Brakhage A. A., Brock M. (2007). Aspergillus fumigatus does not require fatty acid metabolism via isocitrate lyase for development of invasive aspergillosis. Infect. Immun. 75, 1237–1244 10.1128/IAI.01416-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speth C., Kupfahl C., Pfaller K., Hagleitner M., Deutinger M., Wurzner R., et al. (2011). Gliotoxin as putative virulence factor and immunotherapeutic target in a cell culture model of cerebral aspergillosis. Mol. Immunol. 48, 2122–2129 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukardi H., Ung C. Y., Gong Z., Lam S. H. (2010). Incorporating zebrafish omics into chemical biology and toxicology. Zebrafish 7, 41–52 10.1089/zeb.2009.0636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutschbein J., Albrecht D., Potsch M., Guthke R., Aimanianda V., Clavaud C., et al. (2010). Proteome profiling and functional classification of intracellular proteins from conidia of the human-pathogenic mold Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Proteome Res. 9, 3427–3442 10.1021/pr9010684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodisch M., Scherlach K., Winkler R., Hertweck C., Braun H. P., Roth M., et al. (2011). Analysis of the Aspergillus fumigatus proteome reveals metabolic changes and the activation of the pseurotin A biosynthesis gene cluster in response to hypoxia. J. Proteome Res. 10, 2508–2524 10.1021/pr1012812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Gerstein M., Snyder M. (2009). RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 57–63 10.1038/nrg2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg D., Lapp K., Jacobsen I. D., Dahse H. M., Kniemeyer O., Heinekamp T., et al. (2011). Secretome analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus reveals Asp-hemolysin as a major secreted protein. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301, 602–611 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo P. C., Chan C. M., Leung A. S., Lau S. K., Che X. Y., Wong S. S., et al. (2002). Detection of cell wall galactomannoprotein Afmp1p in culture supernatants of Aspergillus fumigatus and in sera of aspergillosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 4382–4387 10.1128/JCM.40.11.4382-4387.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]