John H. Billings, the hospital planner of Johns Hopkins Hospital, is credited with recruiting Sir William Osler (July 12, 1849–December 29, 1919), the Father of Modern Medicine, to Johns Hopkins University in 1888. The entire recruitment was supposed to have been completed in all of two minutes. Dr. Billings, on a very busy day of travel, briefly stopped to pay a visit to Dr. William Osler's rooms on Walnut Street in Philadelphia. As the story goes, Dr. Williams popped his head into Osler's office and without even sitting down, asked, “Will you take charge of the medical department at the Johns Hopkins Hospital?”

When Dr. Osler instantly agreed, Dr. Billings reportedly said, “See (Dr.) Welch about the details; we are to open very soon. I am very busy today, good morning,” and left abruptly to return to the train station.

Osler's illustrious career is legendary. He is credited with creating the concept of the “triple-threat”—a doctor extraordinaire who is equally a skilled educator, scientist, and clinician. He also created and successfully implemented the concept of residency training programs. When Osler joined Johns Hopkins Hospital, the entire department comprised of a small number of faculty members, and each subspecialty division had about three or four physicians initially. At that time there were very few core clinical journals and textbooks, and thus keeping abreast of the latest developments of the field of medicine was an achievable goal. The Oslerian prototype triple-threat physician is now an endangered if not extinct species lost in the chaos of a fragmented health care system, characterized by superspecialization, fraught with perverse incentives and internal conflicts, and inundated with information from the virtual superhighway.

Today, in most subspecialties like cardiology and oncology there are numerous physicians in the field, and as the base population is high, there are sufficient numbers of physicians doing research to build a body of evidence that is critical to the sustenance of any subspecialty. This is not the case in palliative care. The base population of palliative specialists is still very low and most are purely in the clinical realm. The bulk of the responsibility of building the research base as well as training young doctors in the science of palliative care falls largely on the few palliative academicians. Thus, new palliative care physicians entering academic medicine are drafted into the “triple-threat pathway” unbeknownst to them. This small cohort of doctors are caring for rapidly increasing numbers of seriously ill patients in academic hospitals, running hospice and palliative medicine fellowship programs, and educating their trainees and their peers from other subspecialties, while concurrently developing their own investigative portfolio.

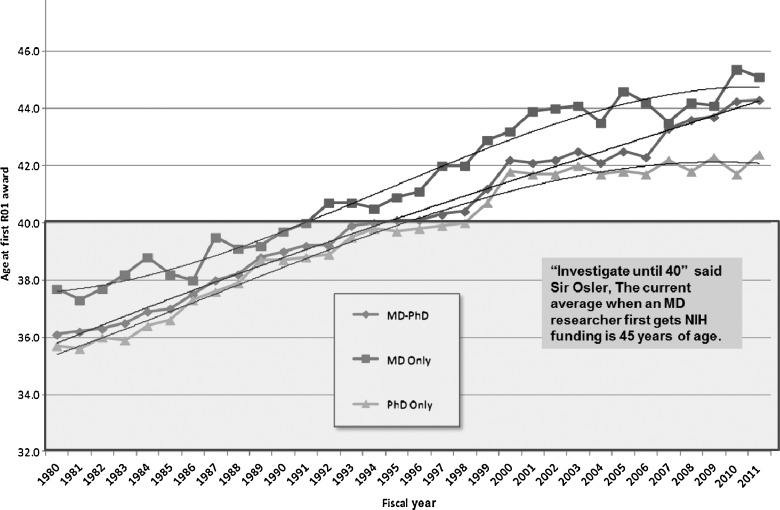

Competition for grant funding, long hours of patient care, administrative demands, and heavy teaching schedules have discouraged some of our most talented young physicians from entering an academic career due to the perceived stressful nature of such positions.1 Successful research funding is the primary currency of the academic realm. However, the federal funding climate has not been favorable to investigators in palliative care. Data show that despite concerted national efforts, the average age at which an MD investigator first obtains R01 (or equivalent) funding has continued to increase from 37 years of age in 1980 to 45 years of age in 2011 (see Figure 1). As highlighted by Gelfman and Morrison2 in this issue of the journal, less than 1% of all National Institutes of Health (NIH) research dollars funds studies in palliative care and alarmingly this trend has not changed in the last ten years as demonstrated in the percentage of palliative care grants funded across the three major funding institutes (NCI, NINR, NIA).

Fig. 1.

Average age of principal investigators with MD, MD-PhD or PhD at the time of their first RO1 equivalent award from NIH (shown for fiscal years 1980 to 2011) continues to increase. There is no NIH center for palliative care yet, though this is an imperative need to empirically understand the pain and symptom palliation of the 2 million Americans who die every year and the several million who are seriously ill.

“Study until 25, investigate until 40, profession until 60, at which age I would have him retired on a double allowance,” said Sir Osler in describing the ideal career trajectory of a doctor. I am not sure how feasible the “investigate until 40” is in the current funding climate. Now imagine for a moment that William Osler, a young doctor, educator, avid reader, and renowned prankster is freshly recruited as a palliative care academician into a large modern health organization. Firstly, the “search committee” will likely take the slow road and the recruitment will drag on for months. Osler will have to visit the recruiting institution and do a dry-as-dust PowerPoint flashing talk about his work. (I like to believe that young Will would have insisted that palliative care is best “learned by the bedside and not in the classroom.”) Next he will sign the contract and will likely be told that his task is to build a brand new palliative care consult service or to exponentially increase the volume of the patients served across venues for the existing program. Osler will likely be given a stingy amount of hypothetical “protected time” (as the clinical and teaching work will already add up to 1.2 full-time equivalent) to begin building his investigative portfolio. As soon as he moves into his office, he will be beset with numerous requests to teach medical trainees, house staff, and hospital staff and on all matters palliative. He will, of course, have to pay his dues to the system by participating in the hospital ethics committee, the medical records committee, and a few other scintillating organizational committees “famous” for their witty repartee and hard rock parties. All this while managing a rapidly growing consult service teeming with patients with complex needs. The annual review will come too soon and his division chief will do the familiar eerie mix of cheerleading and prodding: “I am so pleased that you have become a core member of our community so fast. The hospital is very happy that the consult service is growing rapidly. The dean's office is very pleased that you are taking a leadership role in medical education. What we need to discuss today is about activating your investigative portfolio. What first-author papers have you written in the past year? Do you want to apply for a K award or an R21 for the upcoming NIH application deadline?”

Let us not forget that William Osler was a brilliant man. I hypothesize that Osler would connect with the modern-day William Halsted, professor of surgery; Howard Kelly, professor of gynecology; and William Welch, professor of pathology and would assemble a dream team of palliative care triple-threat faculty successfully doing translational research. I am also certain that Osler would develop a robust clinical palliative care service and win numerous awards for his legendary teaching and mentoring skills. What I am not too sure about is how much quality time William would be able to spend with his wife, Grace. Given that Osler is credited with saying “medicine is best learned at the bedside of the patient,” and extrapolating from the same principle, would he choose to learn about parenting at the bedside of his young sons or would he delegate this task to his wife and their nanny and remotely Skype in from his office to say goodnight to his young sons? Would he choose to prioritize their little league baseball games over the AAHPM, ACP, and SGIM and other professional society meetings? Would he choose to grieve with and support his wife through the loss of one of their sons as a toddler or would he drown his sorrow in his work? It is certainly true that many young palliative academicians struggle to juggle their various work responsibilities while raising young families. What would Osler do when faced with this predicament?

I like to believe that Sir William Osler would have found the magic formula for the ever elusive life-work balance and he would teach it to us all. Osler would work hard to make palliative academia a more faculty-friendly environment. He would insist that educational Relative Value Units (RVUs) be tracked and reimbursed exactly like clinical RVUs so that teaching would never be a gratis effort. He would be a very strong advocate for palliative research and would create model initiatives to activate community-based hospice organizations into becoming research-friendly environments.

Finally, the eternal prankster that he was, Osler would successfully submit a fake grant proposal for a comparative effectiveness trial on palliating of the imaginary phenomenon of “penis captivus” under the pseudonym Egerton Yorrick Davis just as he fooled the Philadelphia Medical News on December 13, 1884.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Periyakoil's work is supported in part by grants RCA 115562A and IR25 MD006857-01 from the National Institutes of Health and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System.

References

- 1.Alpert JS. Coles R. Careers in academic medicine triple threat or double fake. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148(9):1906–1907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelfman L. Du Q. Morrison RS. An update: NIH research funding for palliative medicine, 2006–2010. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(2):125–129. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]