Abstract

Background

Palliative care is evolving from end-of-life care to care provided earlier in the disease trajectory. We compared clinical characteristics between patients referred late in the course of their disease (late referrals, LRs) with patients referred earlier (early referrals, ERs).

Method

Six hundred and ninety-five patients referred to the Supportive Care Center (SCC) with follow-up within 30 days were enrolled. One hundred ERs (expected survival ≥2 years or receiving treatment for curative intent, 14.4%) were compared with a random sample of 100/595 consecutive LRs (all others).

Results

ERs were younger (54.4 versus 59.5, p=0.009), more likely to have head and neck cancer (67% versys 6%, p<0.0001), alcoholism (15% versus 4%, p=0.014), and shorter disease duration until first palliative care consultation (3.8 months versus 16.2 months, p<0.0001). They were also more likely to be referred by radiation oncologists (49% versus 3%, p<0.0001), be referred for treatment-related side effects (70% versus 9%, p<0.0001), and receive more anticancer treatment (74% versus 48%, p=0.0002). Head and neck cancer and reason for referral were independent predictors for ERs (p<0.0001) in multivariate analysis. Baseline Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) symptoms were similar between ERs and LRs. Both groups exhibited improved ESAS scores at follow-up; LRs experienced greater improvement in the symptom distress score (−5.5 versus −3, p=0.007). The median total number of medical visits was higher in ERs (p<0.001); however, the median number of visits per month was higher in LRs (p<0.001).

Conclusions

ERs had different patient characteristics than LRs, and although ERs experience distress similar to that of LRs, their needs and outcomes differ.

Introduction

The prognosis of cancer remains poor with a 5-year survival rate of 68%.1,2_ENREF_1 Patients face physical, psychosocial, and financial distress.3,4 Primary care physicians have traditionally considered palliative care mainly for patients who are no longer receiving treatment or are transitioning to end-of-life care, and this results in short patient survival after referral._ENREF_7_ENREF_5_ENREF_35,6,7

Outpatient palliative care programs are offered by about one-third of comprehensive cancer centers and by fewer regional cancer centers in the United States. 8 In recent years, interest has grown in these programs as a way of providing earlier access for cancer patients.1,3,9–11 A randomized trial performed in patients with advanced lung cancer found that early palliative care improved patient outcomes.12,13 Early palliative care could facilitate the timely management of symptoms, longitudinal psychosocial support, and smooth transition from primary oncology to palliative care avoiding unnecessary aggressive treatment. However, patients at an earlier stage of their disease might need different pharmacological, nonpharmacological, and rehabilitation management as compared with patients with late palliative care referrals. These patients also might impose considerable burden on the existing or planned resources of the palliative care team.

Unfortunately, there are no studies on the characteristics, clinical problems, and outcomes of patients referred early to palliative care. To address this gap in knowledge and characterize this relatively new group of patients (early referrals, ERs), we explored the characteristics and outcomes of patients who were referred to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC)'s Supportive Care Center (SCC) early as compared with patients who received the more traditional late referrals (late referrals, LRs).

Patients and Methods

We received MDACC institutional review board approval for this retrospective study. We reviewed the electronic medical records of consecutive outpatients referred to the SCC between August 20, 2008, and October 31, 2010. Inclusion criteria for our study were a diagnosis of malignant disease and at least one follow-up visit within 30 days of the initial (baseline) SCC consultation.

We categorized patients in two groups: ERs who were receiving or had completed treatment with curative intent or had an expected survival time of more than 2 years; and LRs who were all other patients whose expected survival was less than 2 years at referral. The cut-off of two years insured that the vast majority of patients included in the ER cohort were not from the metastatic, heavily pretreated groups usually referred to palliative care. We reviewed the first 100 consecutive cases of ERs and randomly selected 100 additional cases of LRs from the rest of the consecutive LRs. The medical record numbers of LRs were assigned random numbers; we selected the medical record numbers with the lowest 100 random numbers for our analysis.

Demographics, clinical data, and medical service utilization were obtained from the medical records. We defined advanced disease as the presence of distant metastasis (in the case of solid tumors) or as refractory or relapsed disease (in the case of hematologic malignancies). Overall survival (OS) times were calculated from two starting points: the date of diagnosis and the date of initial consultation at the SCC; the latest date of follow-up was December 31, 2011. Survival time was censored at the date of the last contact with a patient if death had not occurred.

Assessment tools

Several assessment tools had been used at SCC consultations for each patient included in our study.

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)

The ESAS14 was used on each encounter to evaluate symptom distress. This 0 to 10 self-reported scale records the intensity of each of 10 items. The symptom distress score is the sum of 10 ESAS symptom scores (range, 0–100).

Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale

At the first SCC visit, presence of delirium had been assessed using this validated 10-item, clinician-rated scale designed to quantify the severity of delirium in medically ill patients.15 The total score can range from 0 to 30; for patients with advanced cancer, a total score of 7 is diagnostic of delirium.16

CAGE Questionnaire

Patients at their first SCC visit had filled out the CAGE Questionnaire,17 a validated alcoholism screening tool. This questionnaire consists of four brief questions: 1) Have you ever felt the need to cut down your drinking? 2) Have you ever felt annoyed by criticism of your drinking? 3) Have you ever had guilty feelings about drinking? and 4) Have you ever taken a morning eye-opener? Alcoholism (CAGE positivity) is indicated by “Yes” answers to at least two of these questions for men and at least one for women.

Performance status

Performance status had been collected using the 6-point Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (or Zubrod) performance scale, which ranges from 0 (fully active) to 5 (dead).18 We collected patients' performance status scores on the date of the patients' first SCC visits.

Statistical analysis

Using data from our previous study19_ENREF_9 for a referent value with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI), we based the sample size calculation on the assumption that approximately 15% of referrals to SCC had been early and 85% late. Because we aimed to have 100 patients in the ER cohort, the study population from which both cohorts were derived was considered to be the most recent 700 consecutive patients with malignant disease who had been referred to the SCC before October 2010 and had attended a follow-up visit within 30 days. Thus, after the 100 ERs had been identified, we randomly selected 100 LRs from the rest of all LRs. The expected sample size of approximately 100 per group (ERs and LRs) allowed us to detect effect sizes as small as 0.40 with 80% power when alpha=5%.

We summarized patient characteristics and survival endpoints using descriptive statistics (numbers and percentages, medians and interquartile ranges [IQRs], or means and CIs). We compared baseline differences between ERs and LRs regarding demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, religion, and education), CAGE positivity, primary cancer type and stage, referring service, reason for referral, advanced disease, and treatment status and goal using χ2, Fisher's exact, and Kruskal-Wallis tests. We compared ESAS scores and the median duration between the first referral and second SCC visits using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and analyzed differences of ESAS scores between two groups using independent-sample Mann-Whitney U test. When calculating the baseline and follow-up ESAS item means and CIs we used all available data. Calculation of the p values comparing baseline with follow-up for each ESAS item was based on only those patients who had nonmissing values for both visits for that ESAS item. Differences in disease duration from diagnosis to first SCC consultation, duration from a patient's first MDACC visit to the first SCC consultation, and use of medical services between ERs and LRs were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test. To find the independent predictor for ERs, we analyzed the adjusted logistic regression with dependent variables of age, CAGE positivity, presence of head and neck cancer, presence of anticancer treatment at the time of referral, and disease duration. A p value of<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

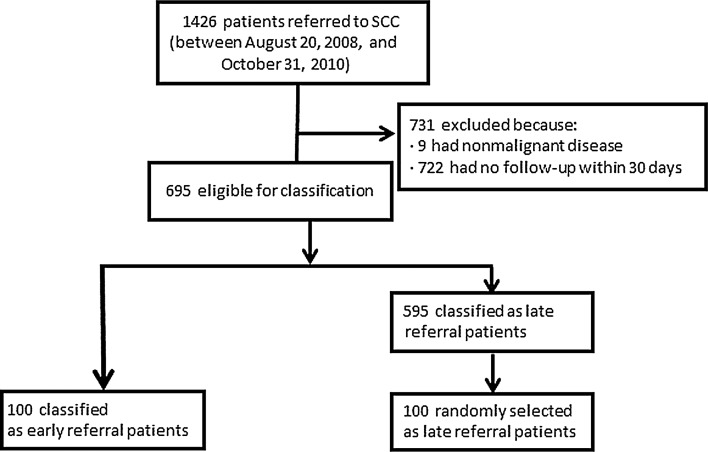

Between August 20, 2008, and October 31, 2010, 1426 patients were referred to the SCC (Fig. 1). Of these, 722 (50.6%) were excluded because they did not have a follow-up within 30 days and 9 (0.01%) because they had no malignant disease, leaving 695 patients eligible for our study. ERs comprised 100/695 eligible patients (14.4%). To create the late referral cohort, we randomly selected 100 patients from the remaining 595 patients, all of whom were LRs.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of patient selection.

ERs were significantly younger than LRs (p=0.009), less likely to be married (p=0.03), and more likely to have CAGE positivity for alcoholism (p=0.014) (Table 1). The distribution of primary cancer also differed: The most common primary tumor site was the head and neck (67%) for ERs and the gastrointestinal tract (30%) for LRs (p<0.0001). Sex, ethnicity, religion, education, stage of cancer at time of diagnosis, and performance status at time of referral to SCC were not significantly different between groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Subjects, by Time of Referral

| Characteristics | All referrals (n=200) | Early referrals (n=100) | Late referrals (n=100) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years | 55.5 | 54.4 | 59.5 | 0.009c |

| (IQR: 49.5–62.6) | (IQR: 48–60.1) | (IQR: 51.9–65.2) | ||

| Female | 94 (47%) | 42 (42%) | 52 (52%) | 0.16a |

| Ethnicity | 0.82b | |||

| White | 149 (75%) | 78 (78%) | 71 (71%) | |

| Hispanic | 22 (11%) | 9 (9%) | 13 (13%) | |

| Black | 19 (10%) | 8 (8%) | 11 (11%) | |

| Asian | 4 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Other | 6 (3%) | 3 (3%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Married | 135 (68%) | 61 (61%) | 74 (74%) | 0.03b |

| Religion | 0.58a | |||

| Christian | 163 (82%) | 83 (83%) | 80 (80%) | |

| Other | 37 (19%) | 17 (17%) | 20 (20%) | |

| Education | 0.30a | |||

| At least some college | 100 (50 %) | 56 (28 %) | 44 (22 %) | |

| No college | 67 (33.5 %) | 32 (16 %) | 35 (17.5 %) | |

| Unknown | 33 (16.5 %) | 12 (6 %) | 21 (6.5 %) | |

| CAGE positivity | 19 (9.5%) | 15 (15%) | 4 (4%) | 0.014b |

| Primary cancer | <0.0001a | |||

| Solid | ||||

| Head and neck | 73 (37%) | 67 (67%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Breast | 25 (13%) | 14 (14%) | 11 (11%) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 34 (17%) | 4 (4%) | 30 (30%) | |

| Lung | 18 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 16 (16%) | |

| Genitourinary | 10 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 8 (8%) | |

| Gynecological | 8 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Sarcoma | 4 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | |

| Other | 16 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 15 (15%) | |

| Hematological | 12 (6%) | 6 (6%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Cancer stage at diagnosis | 0.37b | |||

| I | 11 (5.5%) | 7 (7%) | 4 (4%) | |

| II | 18 (9%) | 7 (7%) | 11 (11%) | |

| III | 39 (19.5%) | 19 (19%) | 20 (20%) | |

| IV | 107 (53.5%) | 62 (62%) | 45 (45%) | |

| Not available | 25 (12.5%) | 5 (5%) | 20 (20%) | |

| Performance status at time of SCC referral | 0.11a | |||

| ≤2 | 140 (70%) | 71 (71%) | 69 (69%) | |

| 3–4 | 15 (7.5%) | 6 (6%) | 9 (9%) | |

| Not available | 45 (22.5%) | 23 (23%) | 22 (22%) | |

| Referring service | <0.0001b | |||

| Medical oncology | 90 (45%) | 36 (36%) | 54 (54%) | |

| Radiation oncology | 52 (26%) | 49 (49%) | 3 (3%) | |

| Clinical center or targeted therapy | 23 (11.5%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (23%) | |

| Hematologic | 9 (4.5%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (5%) | |

| Other | 26 (13%) | 11 (11%) | 15 (15%) | |

| Reason for SCC referral | <0.0001b | |||

| Cancer related | 78 (39%) | 15 (15%) | 63 (63%) | |

| Treatment related | 79 (40%) | 70 (70%) | 9 (9%) | |

| Cancer and treatment related | 29 (15%) | 6 (6%) | 23 (23%) | |

| Not related to cancer | 4 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | |

| Other | 10 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 4 (1%) | |

| Advanced disease at time of SCC referral | 111 (56%) | 12 (12%) | 99 (99%) | <0.0001a |

| Median disease durationd | 6.5 | 3.8 | 16.2 | <0.001c |

| (IQR: 3.0–24.3) | (IQR: 2.4–5.8) | (7.6–42.9) | ||

| Active treatment | 122 (61%) | 74 (74%) | 48 (48%) | 0.0002a |

| Goal of active treatment | <0.0001a | |||

| Curative | 87 (44%) | 87 (87%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Palliative | 113 (57%) | 13 (13%) | 100 (100%) | |

Values are presented as numbers (percentages). The variables that were significant are bolded.

χ2 test, bFisher's exact test, cKruskal-Wallis test.

Duration between diagnosis and first consultation at the Supportive Care Center.

IQR, interquertaile range (25th percentile to ∼75th percentile).

SCC, Supportive Care Center.

The main referring service was radiation oncology for ERs (49%) and medical oncology for LRs (54%) (p<0.0001) (Table 1). The most common reason for referral among ERs was treatment-related side effects (70%); among LRs, it was cancer-related symptoms (63%) (p<0.0001). Compared with LRs, ERs were significantly less likely to have had advanced disease at referral to the SCC (p<0.0001), more likely to be receiving anticancer treatment (p=0.0002), and to be receiving treatment with curative intent (p<0.0001); ERs also had a shorter time between the time of diagnosis and referral than LRs (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Clinical symptoms

Except for lower severity of dyspnea for ERs (p=0.004), there was no significant difference between ERs and LRs in the median baseline score of individual ESAS symptoms or symptom distress score (Table 2). Among ERs, pain (p=0.019) and well-being (p=0.049) improved significantly between the baseline and follow-up SCC visits. Among LRs, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, dyspnea, and sleep disturbance were improved (p≤0.019 for each item). Only one baseline case of delirium was observed using the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale in LRs. The median duration between the first and follow-up SSC visits was 14 days for both ERs and LRs (p=0.793). The outpatient palliative care team successfully managed both ERs' and LRs' symptoms; both groups reported significant symptom improvement at the first follow-up (p<0.05, Table 2). LRs experienced greater improvement in the symptom distress score than ERs (−5.5 [−16.3 to −6] versus −3 [−14 to −4.5]; p=0.007).

Table 2.

Mean ESAS Scores at Initial and Follow-up SSC Consultations, by Time of Referral

| |

All referrals |

Early referrals |

Late referrals |

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESAS symptom | Baseline | Follow-up | P | Baseline | Follow-up | P | Baseline | Follow-up | P | Pa |

| Pain | 5.3 (4.9–5.7) | 4.8 (4.4–5.3) | 0.009 | 5.3 (4.8–5.9) | 4.7 (4.2–5.3) | 0.019 | 5.4 (4.8–5.9) | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 0.159 | 0.764 |

| Fatigue | 5.9 (5.5–6.2) | 5.4 (5.1–5.8) | 0.06 | 5.8 (5.3–6.3) | 5.4 (4.9–6) | 0.244 | 6 (5.4–6.5) | 5.4 (4.9–5.9) | 0.147 | 0.73 |

| Nausea | 2.7 (2.3–3.1) | 2.1 (1.8–2.5) | 0.004 | 2.8 (2.2–3.3) | 2.3 (1.8–2.8) | 0.078 | 2.7 (2.1–3.2) | 2 (1.5–2.5) | 0.018 | 0.624 |

| Depression | 2.8 (2.4–3.1) | 2.2 (1.9–2.6) | 0.006 | 2.8 (2.3–3.4) | 2.6 (2–3.1) | 0.326 | 2.7 (2.1–3.2) | 1.9 (1.4–2.3) | 0.005 | 0.653 |

| Anxiety | 3.4 (3–3.8) | 2.6 (2.2–2.9) | <0.001 | 3.5 (2.9–4.1) | 2.9 (2.3–3.4) | 0.056 | 3.3 (2.7–3.9) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | <0.001 | 0.667 |

| Drowsiness | 4 (3.6–4.4) | 3.6 (3.2–4.1) | 0.11 | 4 (3.4–4.6) | 4 (3.4–4.6) | 0.824 | 4.1 (3.5–4.7) | 3.3 (2.7–3.9) | 0.044 | 0.996 |

| Appetite | 5.3 (4.9–5.7) | 5.1 (4.7–5.6) | 0.36 | 5.2 (4.6–5.9) | 5.1 (4.4–5.7) | 0.537 | 5.4 (4.8–6.1) | 5.2 (4.6–5.8) | 0.468 | 0.702 |

| Well-being | 5 (4.7–5.4) | 4.6 (4.2–5) | 0.02 | 5.2 (4.7–5.7) | 4.6 (4.1–5.2) | 0.049 | 4.9 (4.4–5.4) | 4.6 (4–5.1) | 0.149 | 0.38 |

| Dyspnea | 2.4 (2–2.7) | 1.9 (1.5–2.2) | 0.006 | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | 0.125 | 2.9 (2.3–3.5) | 2.2 (1.7–2.7) | 0.019 | 0.004 |

| Sleep disturbance | 5.1 (4.8–5.5) | 4.7 (4.3–5.1) | 0.012 | 5.1 (4.5–5.6) | 4.8 (4.2–5.3) | 0.262 | 5.2 (4.7–5.8) | 4.6 (4.1–5.2) | 0.013 | 0.899 |

| Total SDS | 41.9 (39.7–44.1) | 37.1 (34.9–39.3) | <0.001 | 41.5 (38.3–44.7) | 37.8 (34.5–41.1) | 0.006 | 42.6 (39.3–45.8) | 36.4 (33.5–39.3) | 0.001 | 0.961 |

Values are means (95% confidence intervals). The variables that were significant are bolded.

Baseline early referral vs. baseline late referral by Mann-Whitney U test.

ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; SCC, Supportive Care Center; SDS, symptom distress score.

Use of services

The median time between first visit to MD Anderson and the initial SCC consultation was significantly longer for LRs (p<0.001), as was the median time between the diagnosis of cancer and the initial consultation (p<0.001) (Table 3). The median follow-up duration between the first SCC visit and death or last day of follow-up was significantly longer for ERs (p<0.001). The total number of visits for medical services was higher for ERs (p<0.001) but the median number of visits per month was lower (p<0.001). ERs also had a higher median number of total visits for nonmedical services (p<0.001). In contrast, LRs had a greater median number of days of hospitalization both in total (p=0.030) and per month (p=0.002). The number of emergency center visits did not differ significantly (Table 3). Overall, ERs had a median of one more visit to the SCC than LRs (Table 3, median, 5 versus 4, p=0.019); however, LRs used palliative care services much more intensely during the short period between first referral and death (Table 3).

Table 3.

Use of Medical and Nonmedical Services during Follow-Up Periods, by Time of Referrals

| Use of services | All referrals | Early referrals | Late referrals | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to SCC consultation, months | ||||

| From 1st MD Anderson visit | 4.4 (2.1–15.7) | 3.3 (1.6–5.2) | 10.3 (3.0–30.1) | <0.001 |

| From diagnosis of cancer | 6.5 (3.0–24.3) | 3.8 (2.4–5.8) | 16.2 (7.6–42.9) | <0.001 |

| Follow-up duration, months from SCC consultation to death/follow-up loss | 12.2 (2.6–12.2) | 12.2 (12.1–12.1) | 2.7 (1.4–7.3) | <0.001 |

| Total visits, no. | ||||

| Medical services | 18 (10–27.8) | 24 (17–33) | 10.5 (7.0–19.0) | <0.001 |

| SCC | 4 (2–7) | 5 (3–8) | 4 (2–6) | 0.019 |

| Other | 13 (6–21) | 19 (12.5–25.5) | 7 (3–13) | <0.001 |

| Nonmedical services | 4 (1–10) | 9 (4–17) | 2 (1–4) | <0.001 |

| Emergency center | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–1) | 0.216 |

| Total admissions, days | 0 (0–6) | 0 (0–3) | 0 (0–9) | 0.030 |

| Visits per month, no. | ||||

| Medical services | 2.9 (1.9–4.7) | 2.1 (1.5–3.0) | 4.3 (2.7–6.0) | <0.001 |

| SCC | 0.8 (0.3–1.5) | 0.42 (0.25–0.74) | 1.48 (0.9–2.5) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.9 (1.2–3.0) | 1.68 (1.10–2.22) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | <0.001 |

| Nonmedical services | 0.77 (0.3–1.7) | 0.82 (0.40–1.56) | 0.64 (0.2–1.9) | 0.579 |

| Emergency Center | 0 (0–1.6) | 0 (0–0.16) | 0 (0–0.23) | 0.863 |

| Admissions per month, days | 0 (0–0.9) | 0 (0–0.25) | 0 (0–2.76) | 0.002 |

Values are medians (interquartile ranges). The variables that were significant are bolded.

Mann-Whitney rank sum test.

SCC, Supportive Care Center.

Factors associated with early referral

ERs were younger, showed more CAGE positivity, were referred more often from radiation oncology, had more diagnoses of head and neck cancer, had more treatment-related symptoms, and had longer disease duration at the time of referral, and were receiving more active treatment than LRs at baseline (Table 1).

In the adjusted logistic regression analysis, head and neck cancer and referral for cancer-related symptoms were independent predictors for early referral, whereas the dependent variables in the model were age, CAGE positivity, head and neck cancer, duration from diagnosis to referral, reason for referral, and presence of anticancer treatment at the time of referral (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors Associated with ERs in Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis

| Factor | Odds Ratio | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.97 | 0.93–1.01 | 0.10 |

| CAGE positivity | 3.22 | 0.66–15.83 | 0.15 |

| Head and neck cancer | 9.15 | 3.09–27.08 | <0.0001 |

| Disease duration | 0.999 | 0.0999–1.000 | 0.06 |

| Reason for referral | |||

| Cancer-related symptoms | 0.09 | 0.03–0.25 | <0.0001 |

| Treatment-related symptoms | 0.87 | 0.03–2.36 | 0.79 |

| Presence of anticancer treatment at the time of referral | 1.83 | 0.76–4.43 | 0.18 |

The variables that were significant are bolded.

ER, early referral.

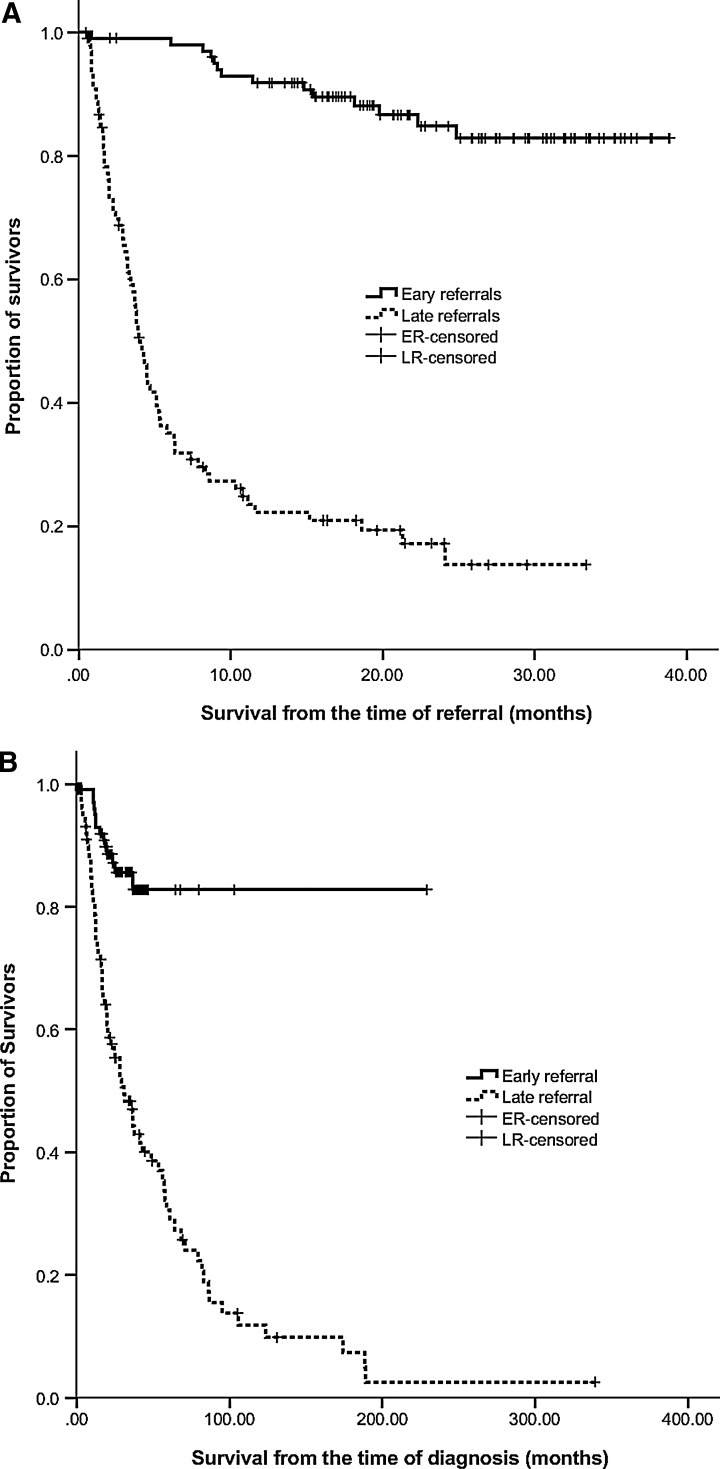

Patient survival

For all 200 patients in our study, the median OS duration from the time of cancer diagnosis was 57.9 months (95% CI: 46.9–68.8) and that from the time of referral was not reached. Regardless of the starting event media, OS was significantly different between ERs and LRs. Median OS duration from the time of referral was 4.1 months (95% CI: 3.4–4.7) for LRs, but was not reached by ERs (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the median OS duration from cancer diagnosis was 30.8 months (95% CI: 19.8–41.8) for LRs, but was not reached by ERs (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival times of patients referred to the Supportive Care Center (SCC), by timeliness of referral. (A) Time from referral to the SCC to follow-up. (B) Time from diagnosis of cancer to follow-up.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to try to define the characteristics, outcomes, and utilization of medical services by cancer patients who were referred early in the course of their disease to outpatient palliative care services. A number of publications have recommended early access to palliative care for cancer patients.12,13,20 However, patients referred early to palliative care might have different demographics and clinical characteristics as compared with those referred late. In addition, ERs might impose a very different burden on the existing and planned services.

In our study, both ERs and LRs had many similar characteristics and ESAS scores suggesting that patients who are early in the course of cancer are as much in need of palliative care as patients who are traditionally referred late in the disease trajectory. This finding provides support to the American Society of Clinical Oncology's recommendation of integration, from the start, of palliative care into oncology care for any patient with metastatic cancer or a high symptom burden.20

Considering the similar severity of symptom burdens upon referral for both ERs and LRs, palliative care physicians need a similarly comprehensive approach to the care of these patients. However, ER patients present unique challenges because their longer survival will require physicians to be especially cautious with regards to long-term side effects such as hypogonadism or dependence in the case of opioids and Cushing syndrome or infection in the case of corticosteroids.

ERs were younger, less likely to be married, more likely to be CAGE positive, and receiving active anticancer treatment. Primary cancer type, referring service, and reason for referral to the SCC were significantly different between ERs and LRs. The LRs in our study showed more frequent use of medical services per month. The main reason for the higher proportion of head and neck cancer in ERs is because these patients undergo aggressive treatment with chemoradiation; severe mucositis results from this treatment and the patients are then referred to palliative care due to their severe symptom distress. The higher frequency of CAGE positivity among ERs might reflect the fact that alcohol drinking is one of the main risk factors for head and neck cancer.21,22 In our study, head and neck cancer accounted for 67% of the primary cancers among ERs but only 6% among the LRs (p<0.0001). In our study, 11/62 patients with head and neck cancer were CAGE positive (15%) versus 8/119 patients with other types of cancer (6.3%) (p=0.042).

A patient's access to the palliative care program is dependent on the primary physician's decision making, which is usually based on his or her assessment of symptom burden through open-ended questioning. There is some evidence that the assessment of a patient's symptom distress should not rely on patient's spontaneous response or on responses to open-ended questions without a screening tool.23–26 Homsi and colleagues23 reported that systemic assessment detects more symptoms than those patients volunteer themselves (median 10 versus 1, p<0.001), and several studies reported that there are discrepancies between a patient's symptom expression and an observer's symptom recognition.24–26 The characteristics of the ERs in our study could be a result of clinician selection bias, creating a possible limitation of our study to determine and compare the characteristics of ERs and LRs. Further study is needed to determine how to effectively and accurately screen all types of patients to identify those who need palliative care early in the course of their disease.

ERs had more medical visits than LRs (24 versus 10.5, p<0.001, Table 3). Moreover, the difference in utilization is likely higher in ER than what we observed because in the median OS of ERs has not been reached (Fig. 2), and our data show that the density of service utilization increases considerably for later-stage patients (Table 3). These findings suggest that outpatient SCC will need to increase space, medical, and nursing resources considerably to be able to accommodate ERs.

Many physicians are not aware that palliative care is relevant to patients at earlier stages of cancer. A survey conducted by our team found that using the term “palliative care” for this service was a barrier to early referral by medical oncologists and midlevel providers.6 As a result, the name of the MDACC palliative care center's outpatient clinic was changed to “Supportive Care Center” in 2008. (The name “Palliative Care” was retained for inpatient services.) This name change resulted in a 41% growth in referrals; in addition, the percentage of patients with early-stage cancer at their first SCC consult increased from approximately 5% to 14%, and_ENREF_11 the median survival time from the initial consultation rose from 4.7 months to 6.2 months among outpatients.19

A limitation of our study is that the population was selected on the basis of their first contact with the SCC. More studies are necessary to define what proportion of patients would benefit from earlier referral to the SCC; future studies should select patients on the basis of prognosis and/or symptom distress. This information could be helpful in guiding access for both ERs and LRs to the SCC at the appropriate times.

We conclude that ERs have different demographic and clinical characteristics and different utilization of medical services as compared with LRs. This information should be considered in the planning for the establishment/expansion of existing outpatient palliative care programs.

Acknowledgments

Eduardo Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant numbers RO1NRO10162-01A1, RO1CA122292-01, RO1CA124481-01, and in part by the MD Anderson Cancer Center support grant number CA016672.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Bruera is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants RO1NRO10162-01A1, RO1CA122292-01, and RO1CA124481-01. This study is also supported by the MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant CA016672. The funding sources were not involved in the conduct of the study of development of the submission.

References

- 1.Walling A. Lorenz KA. Dy SM. Naeim A. Sanati H. Asch SM. Wenger NS. Evidence-based recommendations for information and care planning in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3896–3902. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R. Ward E. Brawley O. Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: The impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whelan TJ. Mohide EA. Willan AR. Arnold A. Tew M. Sellick S. Gafni A. Levine MN. The supportive care needs of newly diagnosed cancer patients attending a regional cancer center. Cancer. 1997;80:1518–1524. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1518::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alifrangis C. Koizia L. Rozario A. Rodney S. Harrington M. Somerville C. Peplow T. Waxman J. The experiences of cancer patients. QJM. 2011;104:1075–1081. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field MJ. Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadul N. Elsayem A. Palmer JL. Del Fabbro E. Swint K. Li Z. Poulter V. Bruera E. Supportive versus palliative care: What's in a name? A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer. 2009;115:2013–2021. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hillier R. Palliative medicine. BMJ. 1988;297:874–875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6653.874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hui D. Elsayem A. De la Cruz M. Berger A. Zhukovsky DS. Palla S. Evans A. Fadul N. Palmer JL. Bruera E. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy MH. Back A. Benedetti C, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:436–473. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 2nd. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project; 2009. [Mar 1;2012 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris FD. Bruera E. Cherny N. Cummings C. Currow D. Dudgeon D. Janjan N. Strasser F. von Gunten CF. Von Roenn JH. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temel JS. Greer JA. Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Temel JS. Greer JA. Admane S. Gallagher ER. Admane S. Jackson VA. Dahlin CM. Blinderman CD. Jacobsen J. Pirl WF. Billings JA. Lynch TJ. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruera E. Kuehn N. Miller MJ. Selmser P. Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breitbart W. Rosenfeld B. Roth A. Smith MJ. Cohen K. Passik S. The Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;13:128–137. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00316-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lawlor PG. Nekolaichuk C. Gagnon B. Mancini IL. Pereira JL. Bruera ED. Clinical utility, factor analysis, and further validation of the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale in patients with advanced cancer: Assessing delirium in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2859–2867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oken MM. Creech RH. Tormey DC. Horton J. Davis TE. McFadden ET. Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalal S. Palla S. Hui D. Nguyen L. Chacko R. Li Z. Fadul N. Scott C. Thornton V. Coldman B. Amin Y. Bruera E. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist. 2011;16:105–111. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith TJ. Temin S. Alesi ER. Taylor DH., Jr Downey W. Abernethy AP. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hashibe M. Brennan P. Benhamou S. Castellsague X. Chen C. Curado MP. Dal Maso L. Daudt AW. Fabianova E. Fernandez L. Wünsch-Filho V. Franceschi S. Hayes RB. Herrero R. Koifman S. La Vecchia C. Lazarus P. Levi F. Mates D. Matos E. Menezes A. Muscat J. Eluf-Neto J. Olshan AF. Rudnai P. Schwartz SM. Smith E. Sturgis EM. Szeszenia-Dabrowska N. Talamini R. Wei Q. Winn DM. Zaridze D. Zatonski W. Zhang ZF. Berthiller J. Boffetta P. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle P. Macfarlane GJ. Zheng T. Maisonneuve P. Evstifeeva T. Scully C. Recent advances in epidemiology of head and neck cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1992;4:471–477. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homsi J. Walsh D. Rivera N. Rybicki LA. Nelson KA. Legrand SB. Davis M. Naughton M. Gvozdjan D. Pham H. Symptom evaluation in palliative medicine: patient report vs. systematic assessment. Support Care Cancer. 2006;4:444–453. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strömgren AS. Groenvold M. Sorensen A, et al. Symptom recognition in advanced cancer. A comparison of nursing records against patient self-rating. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:1080–1085. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.450905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strömgren AS. Groenvold M. Pedersen L. Andersen L. Does the medical record cover the symptoms experienced by cancer patients receiving palliative care? A comparison of the record and patient self-rating. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sneeuw KCA. Sprangers MAG. Aaronson NK. The role of health care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;55:1130–1143. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00479-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]