Abstract

Background

Among euthyroid pregnant women in a large clinical trial, free thyroxine (FT4) measurements below the 2.5th centile were associated with a 17 lb higher weight (2.9 kg/m2) than in the overall study population. We explore this relationship further.

Methods

Among 9351 women with second trimester thyrotropin (TSH) measurements between 1st and 98th centiles, we examine: (i) the weight/FT4 relationship; (ii) percentages of women in three weight categories at each FT4 decile; (iii) FT4 concentrations in three weight categories at each TSH decile; and (iv) impact of adjusting FT4 for weight—in the reference group and in 190 additional women with elevated TSH measurements.

Results

FT4 values decrease steadily as weight increases (p<0.0001 by ANOVA) among women in the reference group (TSH 0.05–3.8 IU/L). TSH follows no consistent pattern with weight. When stratified into weight tertiles, 48% of women at the lowest FT4 decile are heavy; the percentage decreases steadily to 22% at the highest FT4 decile. Median FT4 is lowest in heaviest women regardless of the TSH level. In the reference group, weight adjustment reduces overall variance by 2.9%. Fewer FT4 measurements are at either extreme (below the 5th FT4 centile: 4.8% before adjustment, 4.7% after adjustment; above the 95th FT4 centile: 5.0% and 4.7%, respectively). Adjustment places more light weight women and fewer heavy women below the 5th FT4 centile; the converse above the 95th centile. Between TSH 3.8 and 5 IU/L, the FT4 percentage below the 5th FT4 centile is not elevated (3.8% before adjustment, 3.1% after adjustment). Percentage of FT4 values above the 95th centile, however, is lower (1.5% before adjustment, 0.8% after adjustment). Above TSH 5 IU/L, 25% of women have FT4 values below the 5th FT4 centile; weight adjustment raises this to 30%; no FT4 values remain above the 95th FT4 centile.

Conclusions

During early pregnancy, TSH values are not associated with weight, unlike nonpregnant adults. Lower average FT4 values among heavy women at all TSH deciles partially explain interindividual differences in FT4 reference ranges. The continuous reciprocal relationship between weight and FT4 explains lower FT4 with higher weight. Weight adjustment refines FT4 interpretation.

Introduction

Thyrotropin (TSH) is the most reliable measurement for assessing thyroid function. Thyroxine (T4) measurement is relatively insensitive and is usually ordered as a secondary test, when a TSH value is above or below the reference range. Within-person fluctuations in total T4 concentrations over a 1-year period account for only about half of the overall population reference range (1). As a result, a T4 concentration in the lower part of the population reference range might actually be below an individual's own reference range and represent an abnormally low value. The opposite problem might occur with values at the upper part of the reference range that are, in fact, abnormally high. Unfortunately, this source of biologic variability cannot be accounted for when providing interpretations for clinical purposes, as there is no practical way to establish baseline reference ranges for each individual within a given population.

In 2008, we observed a relationship between low free T4 (FT4) concentration and higher maternal weight and body mass index (BMI) during early pregnancy (15–20 gestational weeks) (2,3). In that study, BMI averaged 2.9 kg/m2 higher (17 lb) in association with FT4 concentrations below the 2.5th centile. Other recent studies have documented similar relationships (4–7). Depending upon the nature of this relationship across the broader BMI or weight spectrum, a maternal weight effect might partially explain variations among individual FT4 ranges, thereby accounting for a portion of overall population variability. Under such circumstances, adjusting for BMI could reduce overall variability and refine interpretation of FT4 results. There is precedence for this concept, as prenatal screening for Down syndrome using maternal serum markers currently includes several fetoplacental products whose concentrations vary with maternal weight and are adjusted to take weight into account (8,9). The present study examines the relationship between maternal weight and FT4 more extensively and explores the extent to which weight adjustment might refine FT4 interpretation.

Materials and Methods

Women were participants in the multicenter FaSTER trial, as previously described (2,3). Enrollment was limited to women with singleton pregnancies. Maternal serum samples were collected at 11–14 weeks' and 15–20 weeks' gestation. At five of the 15 recruitment centers, a total of 14,554 participants were asked to give supplementary consent to allow their residual sample and pregnancy-related information to be used for additional research studies. Samples from the 10,990 women who consented at those centers (Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY; Swedish Medical Center, Seattle WA; LDS Hospital, Salt Lake City, UT; Utah Valley Regional Medical Center, Provo, UT; and McKay Dee Hospital, Ogden, UT) were eligible. Women who did not consent and those whose pregnancies were affected by Down syndrome or other chromosome or structural abnormalities were excluded. Inclusion criteria for the reference population required the following: (i) TSH and FT4 measurement available and gestational age established by ultrasound (10,062 subjects), (ii) no known thyroid disease (9670 subjects), and (iii) TSH between 1st and 98th centiles (9388 subjects), and (iv) weight available (9351 subjects). The TSH reference group included women with elevated thyroid antibody concentrations.

The TSH reference range 95% was 0.05–3.80 IU/L (second trimester, 9351 women). A weight adjustment equation for FT4 derived from that same reference population was then applied to 190 subjects without known thyroid deficiency whose TSH measurements were above the 98th centile.

Samples were collected between 1999 and 2002, stored at −80°C, and tested between July 2004 and May 2005 (storage was for 3–6 years). Levels of TSH and FT4 were measured using the Immulite 2000 methodology (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). Normative data involving these analytes have been published separately for this cohort (3), along with details of assay performance. Weights and heights from these women were recorded at the time of initial sampling in the first trimester.

The lower limit for interpreting TSH measurements was 0.01 mIU/L. Long-term coefficients of variation were 5.3%, 6.9%, and 3.8% at TSH concentrations of 0.53, 4.5, and 21.9 mU/L; 8.1%, 6.5%, and 7.9% at FT4 concentrations of 11.6, 23.2, and 41.2 pmol/L.

Differences in FT4 subgroups were assessed by ANOVA before and after weight adjustment. In some analyses, FT4 and TSH measurements were expressed as multiples of the median (MoM), as a normalizing function. All data stratifications and analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, NC). To adjust for weight, FT4 measurements were first converted to MoM by dividing by 13.029 (the overall median FT4 measurement in pmol/L, assigned a value of 1.0) (8). Then, median MoM values were calculated at 20 lb intervals between 80 and 300 lb. An additional median MoM value was determined for women >300 lb (centered at 317 lb). The best fit curve was as follows: FT4 MoM/(0.85988+20.38592×[1/wt]). Values from women in the reference group (expressed as MoM) were adjusted and converted back to pmol/L by multiplying by 13.029.

Results

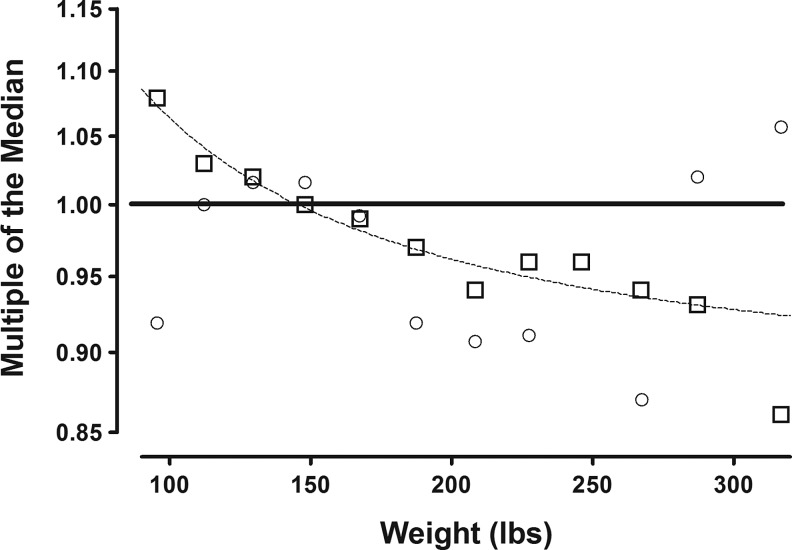

In this section, all analyses utilize thyroid measurements in serum samples obtained early in the second trimester (15–20 weeks gestation). Table 1 describes relevant characteristics of the cohort. Figure 1 shows the relationship between the study population's weight distribution and FT4 and TSH measurements. In the figure, open boxes (FT4) and circles (TSH) represent median FT4 and TSH measurements, expressed as multiples of the overall study population median (MoM). These data are plotted against the respective mean weights of 20 lb weight intervals between 80 and 300 lb; women >300 lb are combined in a single group at 317 lb. Median FT4 MoM values among the 12 weight categories differ significantly and are consistently lower as weight increases (p<0.0001 by ANOVA). The dotted line describes the best fit curve for the relationship between FT4 and maternal weight. Figure 1 also shows that median TSH MoM values follow no consistent pattern in relation to weight.

Table 1.

Selected Characteristics of Women in the Second Trimester Reference Group

| Number of women | 9351 |

| Age, years [mean (median)] | 29.0 (29.0) |

| Gestational age, week [mean (range)] | 16.6 (15–19) |

| TSH, IU/L [mean (range)] | 1.35 (0.05–3.8) |

| FT4, pmol/L [mean (range)] | 13.1 (5.9–49.1) |

| Ethnicity (%) | |

| White | 87.1 |

| African American | 6.9 |

| Hispanic | 1.6 |

| Other | 4.4 |

| Primigravida (%) | 32.1 |

| Weight, lb [mean (median)] | 149.8 (143.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 [mean (median)] | 24.8 (23.5) |

| Education, years (mean) | 14.6 |

| Married (%) | 91.6 |

| Current smoker (%) | 3.0 |

TSH, thyrotropin; FT4, free thyroxine.

FIG. 1.

The relationship between maternal weight and free thyroxine (FT4) and thyrotropin (TSH) concentrations at 15–20 weeks gestation. The X axis shows mean maternal weight at 20 lb intervals between 80 and 300 lb (and also at 317 lb). Open boxes (□) represent median FT4 values at each weight interval, expressed as multiples of the overall study population median (multiples of the median [MoM]). Samples for FT4 measurements were obtained between 15 and 20 weeks' gestation. The dotted line describes the best fit curve for the weight/FT4 relationship. Open circles (○) represent median TSH measurements obtained from the same samples. No consistent relationship with weight is apparent.

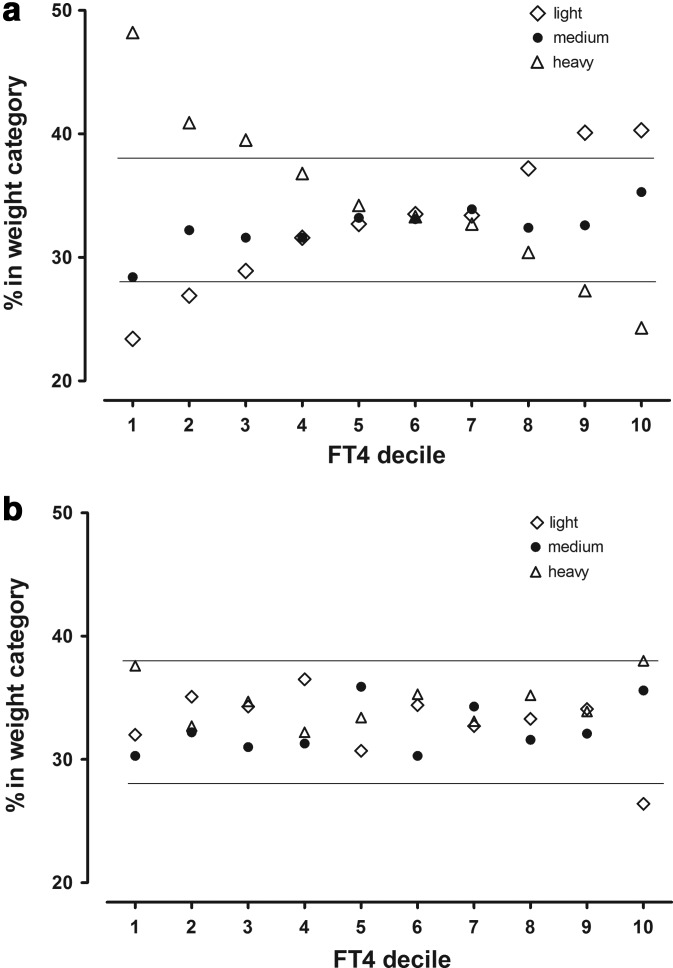

Figure 2a shows the percentage of women in three weight categories (tertiles) at each FT4 decile. Numbers and percents of women and median weights in each weight category are as follows: Light (122 lb), 3081 (32.9%); Medium (142 lb), 3035 (32.5%); Heavy (175 lb), 3235 (34.6%). If there were no weight relationship, the women within each FT4 decile would be represented approximately equally in each of the three weight categories. However, within the lowest FT4 decile, 48% of the women are in the Heavy weight category, 30% in the Medium category, and 22% in the Light category. As FT4 deciles increase, the percentage of Heavy women steadily decreases, while the percentage of Light women steadily increases. No threshold is apparent. At the highest FT4 decile, 22% of the women are in the Heavy weight category, with 35% in the Medium, and 43% in the Light categories. Figure 2b shows the impact of weight correction on the percentages of women in each weight category at various FT4 deciles. The clear pattern in Figure 2a is no longer present, and nearly all percentages are now within boundaries expected in the absence of a FT4/weight relationship.

FIG. 2.

(a) Proportional representation of three categories of maternal weight within FT4 deciles 1–10. The 9351 second-trimester women with TSH measurements between the 1st and 98th centiles are stratified into tertiles, according to weight (Table 2). Open diamonds (⋄) represent Light women, closed circles (●) Medium weight women, and open triangles (▵) Heavy women. The x-axis shows FT4 intervals by decile, while the y-axis shows percentages of women in the three weight categories within each FT4 decile. In the absence of a relationship between FT4 and weight, roughly a third of women in each weight category should be represented at all deciles. Horizontal lines at 28% and 37% denote expected range of fluctuation in the absence of a weight relationship. (b) Proportional representation of three categories of maternal weight within FT4 deciles 1–10 following weight adjustment of FT4.

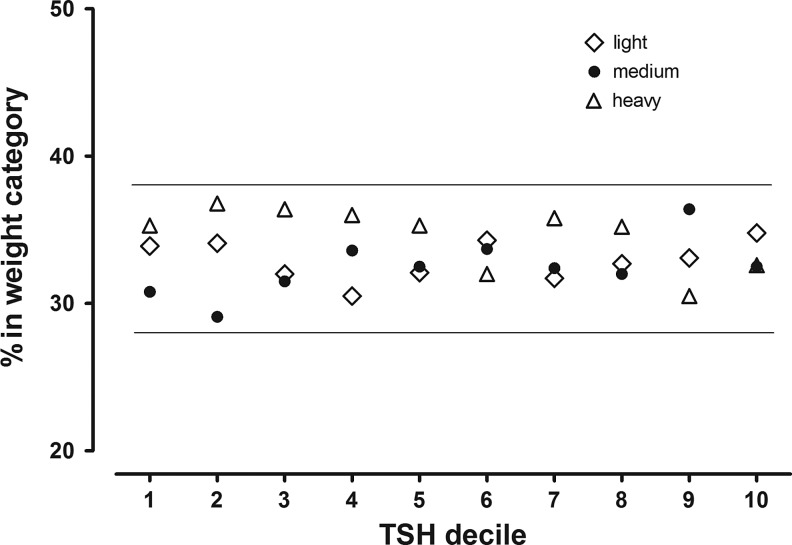

Figure 3 shows the percentages of women in the same three weight categories at each TSH decile. In contrast to the FT4 distribution, approximately one-third of the women in each weight category are in each TSH decile, and there is no clearly defined weight relationship. The percentage of women in the Heavy weight category, for example, varies marginally and shows no trend between 30% and 35%, with 34% in the first TSH decile and 35% in the 10th decile.

FIG. 3.

Proportional representation of three categories of maternal weight within TSH deciles 1–10. This is similar to Figure 2a, except that TSH deciles are shown on the x-axis. Women in the three weight categories are represented proportionally at all TSH deciles, indicating lack of a relationship with weight.

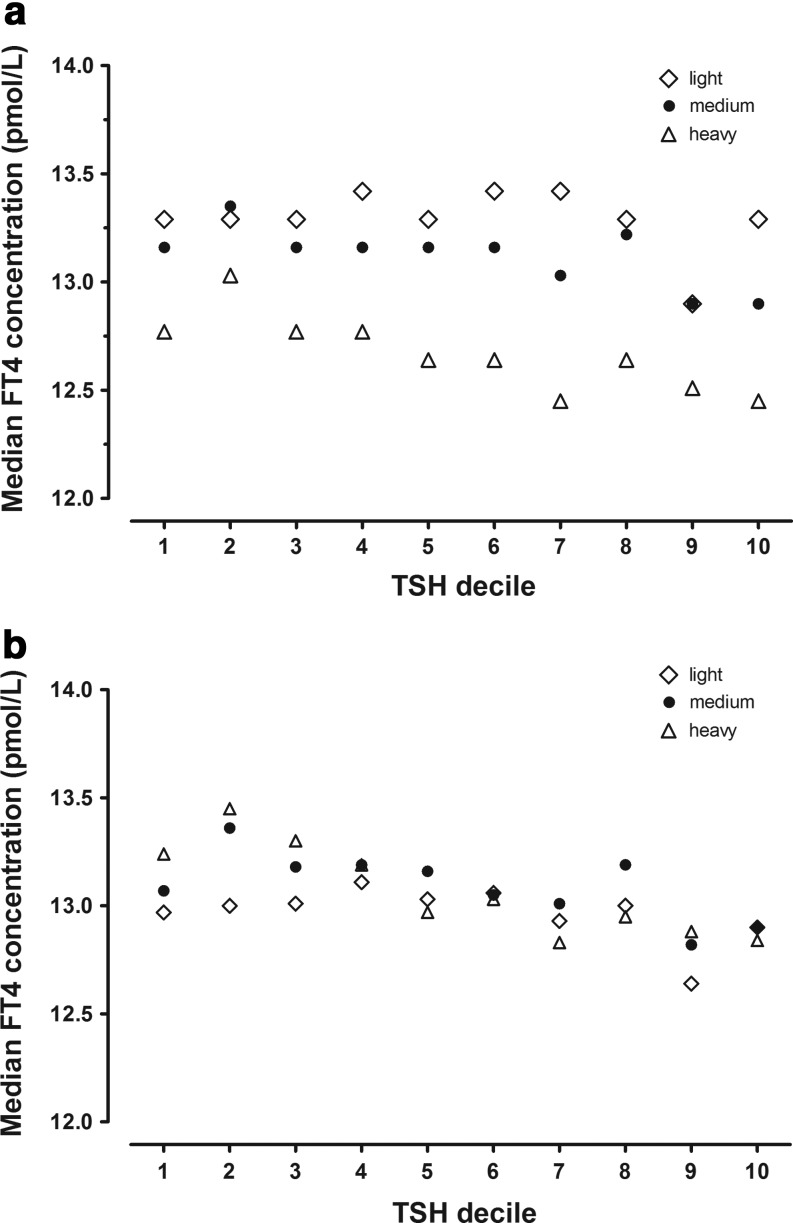

Focusing further on the FT4-weight relationship, Figure 4a shows that median FT4 concentrations are lowest in the Heavy weight category at all TSH deciles. The converse is true for women in the Light category, where FT4 values are highest in nine of the 10 TSH deciles. There is only minor variation in percents of women in the respective weight categories by TSH decile. Figure 4b shows the impact of weight adjustment on these relationships. There is a reduction in FT4 variation, and there is no longer a clear hierarchy of weight-related FT4 concentrations.

FIG. 4.

(a) Median FT4 concentrations at three categories of maternal weight within TSH deciles 1–10 between 15 and 20 weeks gestation. The 9351 women with TSH measurements between the 1st and 98th centiles are stratified into tertiles, according to weight (Table 2). Open diamonds (⋄) represent Light women, closed circles (●) Medium weight women, and open triangles (▵) Heavy women. The x-axis shows TSH intervals by decile, while the y-axis shows median FT4 concentrations for each weight category within each TSH decile. At all deciles, relative FT4 concentrations are lowest among Heavy women. (b) Median FT4 concentrations at three categories of maternal weight within TSH deciles 1–10 between 15 and 20 weeks gestation following weight adjustment of FT4.

Table 2 examines the impact of adjusting FT4 by maternal weight on the percent of FT4 values below the 5th and above the 95th centiles. Among second trimester women in the reference group, adjustment places more Light and fewer Heavy women below the 5th FT4 centile; the converse—fewer Light women and more Heavy women—occurs above the 95th centile after adjustment. Overall, after weight adjustment, slightly fewer women have FT4 measurements at either extreme; the overall reduction in population variance is 2.9%. Among TSH concentrations between 3.8 and 5 IU/L, weight adjustment has little overall impact on the percentage of women with FT4 values at either extreme. The overall percentage of FT4 values above the 95th centile is considerably lower than the reference group both before and after weight adjustment, while the percentage of values below the 5th centile is not elevated. Among women with TSH measurements above 5 IU/L, 31.7% have FT4 values below the 5th centile; weight adjustment does not alter this overall percentage. However, more Light weight women and fewer Heavy women have FT4 values below the 5th centile following adjustment. There are no FT4 values above the 95th centile after adjustment.

Table 2.

Percent of Second-Trimester Free Thyroxine Measurements Below the 5th Centile in Each Weight Category, Before and After Adjusting for Weight, Comparing Reference Group Women with Women with Thyrotropin Concentration >98th Centile

| |

TSH reference, range 0.05–3.8 IU/L |

TSH elevated, range 3.8–5.0 IU/L |

TSH elevated, range ≥5.0 IU/L |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight category | n | Pre (%) | Post (%) | n | Pre (%) | Post (%) | n | Pre (%) | Post (%) |

| FT4 measurements below 5th centile | |||||||||

| Light | 3081 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 54 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 19 | 21.0 | 31.6 |

| Medium | 3035 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 41 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 20 | 40.0 | 40.0 |

| Heavy | 3235 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 35 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 21 | 33.3 | 23.8 |

| All | 9351 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 130 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 60 | 31.7 | 31.7 |

| FT4 measurements above 95th centile | |||||||||

| Light | 3081 | 5.7 | 3.2 | 54 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 19 | 5.3 | 0.0 |

| Medium | 3035 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 41 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Heavy | 3235 | 3.5 | 4.9 | 35 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| All | 9351 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 130 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 60 | 1.7 | 0.0 |

Pre, before adjusting for weight; Post, after adjusting for weight.

We also performed FT4 and TSH measurements at 11–14 weeks gestation on the 9351 women in the reference group and the 190 women with elevated TSH values. Average TSH measurements were lower and FT4 measurements were higher, but the patterns shown in Figures 1–4 above for the second trimester were similar (data not shown; available upon request).

Discussion

During early pregnancy, there is an inverse relationship between maternal weight and FT4. The curve defining this relationship is similar to that between maternal weight and unconjugated estriol, which is due to dilution of a fetoplacental product in the maternal blood volume (8). Unconjugated estriol is one component of the screening test for Down syndrome. The relationship of this marker (and other screening markers) with maternal weight is routinely taken into account before test interpretation (8,9).

In our study, FT4 was measured by a direct immunoassay that did not require a dialysis step. Assays of this type are prone to interference. For example, altered concentrations of binding proteins, such as albumin and thyroxine-binding globulin that occur during pregnancy, can occasionally yield erroneous FT4 measurements. This problem is of special concern when interpreting individual test results during pregnancy. In spite of this shortcoming, it is recognized that immunoassays of this type perform reasonably well under most circumstances (10). They are the only practical option for analyzing large numbers of samples in population studies. Should it become possible to adapt newer assays (such as GC/mass spectrometry) for large throughput, we speculate that the FT4/weight relationship will become more sharply defined, due to a reduction in assay variance.

In contrast to fetoplacental markers, circulating maternal FT4 might be expected to be under sufficient feedback regulation to negate a potential maternal weight-related dilution effect. However, the presence of a dilution effect for FT4 is strongly supported by the stepwise decreasing percentage of heavy women within a given FT4 decile as FT4 deciles increase (coupled with an increasing percentage of light weight women). There is no threshold. At every decile of TSH, FT4 concentrations are lowest among women in the highest weight group, suggesting that equilibrium in the FT4/TSH relationship might be achieved at different FT4 concentrations, depending upon weight.

TSH did not relate to maternal weight in our study. This differs from the positive relationship previously reported for nonpregnant adults in two studies (11,12), but not in a third (13). Bassols et al. report similar findings to ours during pregnancy and speculate that this discrepancy is due to a weak TSH-like effect of human chorionic gonadotropin (4). We also consider human chorionic gonadotropin to be the most likely explanation for absence of a weight effect on TSH, as it has a well-documented impact on both TSH and FT4 during early pregnancy.

Applying weight adjustment to the reference group normalizes the various weight categories in predictable fashion and results in a small overall reduction in FT4 variance within the population (2.9%). With even mild TSH elevation, percentages of FT4 values above the 95th centile are substantially reduced; the impact of adjustment in that situation is apparent only among women in the light weight category, due to a total absence of medium and heavy weight women with such high FT4 values. Among women with TSH measurements above 5.0 IU/L, adjusting for weight does not affect heavy women, but increases the percentages of light and medium weight women with FT4 values below the 5th centile, thereby raising the overall rate of low values. In general, the most noticeable impact of FT4 adjustment is expected to occur in the tails of a population's weight distribution and especially in the upper tail, as it is less finite than the lower tail.

The BMI/FT4 relationship in the present cohort was similar to the weight/FT4 relationship (data not shown). Serum markers to screen prenatally for Down syndrome are routinely adjusted using maternal weight, rather than BMI. Our analyses, therefore, all use weight instead of BMI for consistency with existing prenatal screening practice. In the present cohort, the rate of obesity (BMI≥30) is 14%. A recent study has documented a 30% rate of obesity in a cohort of over 5000 pregnant women (7). In such circumstances, the overall impact of weight adjustment on reclassification of the FT4 concentration is likely to be greater than in the current study.

Dilution has not previously been proposed as an explanation for lower FT4 levels in association with obesity in pregnant women. Instead, it has been speculated that lower FT4 concentrations in euthyroid individuals might be the primary event, contributing to metabolic changes that favor less efficient energy utilization and promote weight gain. To date, only observational studies of the relationship have been published; these data do not allow a distinction to be made between causality and an association. A Korean study involving nonpregnant women documented a stepwise inverse association between FT4 quartiles and BMI, but attributed this to an obesity effect (13).

In their analysis of a cohort of pregnant women, Bassols et al. provide data demonstrating a less favorable metabolic phenotype in association with lower FT4, as defined by higher fasting and postload insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, and triglycerides, and with lower adiponectin (4). Among the 321 early third trimester euthyroid women in that study, the free triiodothyronine (FT3)/FT4 ratio was independently associated with BMI in a multiple regression model, suggesting that relatively increased FT3 production may compensate for lower FT4 concentrations. In addition, Mannisto et al. documented a stepwise increase in FT3 and decrease in FT4 according to BMI category among 5072 pregnant women. While the present dataset lacks FT3 measurements to further explore the possibility of this compensatory mechanism, the observed change in the TSH/FT4 set point with weight is consistent with this. Observational studies in euthyroid nonpregnant adults have also documented an association between low FT4 and the components of the metabolic syndrome (14–16).

Strengths of our observational study include a large, unbiased cohort of women during early pregnancy, thyroid measurements obtained from all of the women, and standardized demographic information available from all study subjects. Shortcomings include the inability to correlate FT4 with symptomatology, with or without weight adjustment. An average of 4 weeks elapsed between the time of recording weight and obtaining a second trimester sample for FT4 and TSH measurement. During that interval, an average weight shift of four pounds is expected. Given that comparisons in our study are relative, this ought not to disturb reported relationships. Given the nonspecific nature of clinical signs and symptoms that occur with thyroid deficiency, a large randomized trial would be needed to explore clinical correlations. Our study shows that the FT4 concentration decreases across a broad range of maternal weight, indicating a dilution effect. Among women in the reference population, adjusting FT4 measurements for weight slightly reduces overall variance and reclassifies a proportion of women with FT4 values below the 5th centile. Adjustment also results in reclassification of FT4 values below the 5th centile among women with TSH measurements >5 IU/L. Accounting for weight may represent a potential refinement in test interpretation. Although the consistency of the FT4/weight relationship between the first and second trimesters serves as initial validation, it will be important to verify this observation in a separate population.

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by Grant Number RO1 HD 38652 from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Andersen S. Bruun NH. Pedersen KM. Laurberg P. Biologic variation is important for interpretation of thyroid function tests. Thyroid. 2003;13:1069–1078. doi: 10.1089/105072503770867237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleary-Goldman J. Malone FD. Lambert-Messerlian G. Sullivan L. Canick J. Porter TF. Luthy D. Gross S. Bianchi DW. D'Alton ME. Maternal thyroid hypofunction and pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:85–92. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181788dd7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambert-Messerlian G. McClain M. Haddow JE. Palomaki GE. Canick JA. Cleary-Goldman J. Malone FD. Porter TF. Nyberg DA. Bernstein P. D'Alton ME. First-, second-trimester thyroid hormone reference data in pregnant women: a FaSTER (First-, Second-Trimester Evaluation of Risk for aneuploidy) Research Consortium study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(62):e61–e66. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassols J. Prats-Puig A. Soriano-Rodriguez P. Garcia-Gonzalez MM. Reid J. Martinez-Pascual M. Mateos-Comeron F. de Zegher F. Ibanez L. Lopez-Bermejo A. Lower free thyroxin associates with a less favorable metabolic phenotype in healthy pregnant women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3717–3723. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mannisto T. Surcel HM. Ruokonen A. Vaarasmaki M. Pouta A. Bloigu A. Jarvelin MR. Hartikainen AL. Suvanto E. Early pregnancy reference intervals of thyroid hormone concentrations in a thyroid antibody-negative pregnant population. Thyroid. 2011;21:291–298. doi: 10.1089/thy.2010.0337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casey BM. Dashe JS. Spong CY. McIntire DD. Leveno KJ. Cunningham GF. Perinatal significance of isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia identified in the first half of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1129–1135. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000262054.03531.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig WY. Allan WC. Kloza EM. Pulkkinen AJ. Waisbren S. Spratt DI. Palomaki GE. Neveux LM. Haddow JE. Mid-gestational maternal free thyroxine concentration and offspring neurocognitive development at age two years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E22–E28. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neveux LM. Palomaki GE. Larrivee DA. Knight GJ. Haddow JE. Refinements in managing maternal weight adjustment for interpreting prenatal screening results. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:1115–1119. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0223(199612)16:12<1115::AID-PD3>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haddow JE. Palomaki GE. Biochemical screening for neural tube defects, Down syndrome. In: Rodeck CH, editor; Whittle MJ, editor. In Fetal Medicine: Basic Science and Clinical Practice. Churchill Livingstone; London: 1999. pp. 373–388. Vol. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stagnaro-Green A. Abalovich M. Alexander E. Azizi F. Mestman J. Negro R. Nixon A. Pearce EN. Soldin OP. Sullivan S. Wiersinga W American Thyroid Association Taskforce on Thyroid Disease During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;21:1081–1125. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knudsen N. Laurberg P. Rasmussen LB. Bulow I. Perrild H. Ovesen L. Jorgensen T. Small differences in thyroid function may be important for body mass index and the occurrence of obesity in the population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4019–4024. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makepeace AE. Bremner AP. O'Leary P. Leedman PJ. Feddema P. Michelangeli V. Walsh JP. Significant inverse relationship between serum free T4 concentration and body mass index in euthyroid subjects: differences between smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:648–652. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shon HS. Jung ED. Kim SH. Lee JH. Free T4 is negatively correlated with body mass index in euthyroid women. Korean J Int Med. 2008;23:53–57. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2008.23.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roos A. Bakker SJ. Links TP. Gans RO. Wolffenbuttel BH. Thyroid function is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in euthyroid subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:491–496. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garduno-Garcia JJ. Alvirde-Garcia U. Lopez-Carrasco G. Padilla Mendoza ME. Mehta R. Arellano-Campos O. Choza R. Sauque L. Garay-Sevilla ME. Malacara JM. Gomez-Perez FJ. Aguilar-Salinas CA. TSH and free thyroxine concentrations are associated with differing metabolic markers in euthyroid subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163:273–278. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambrosi B. Masserini B. Iorio L. Delnevo A. Malavazos AE. Morricone L. Sburlati LF. Orsi E. Relationship of thyroid function with body mass index and insulin-resistance in euthyroid obese subjects. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:640–643. doi: 10.1007/BF03346663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]