Abstract

Background

Incarceration is associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Incarceration may contribute to STI/HIV by disrupting primary intimate relationships that protect against high-risk partnerships.

Methods

In an urban sample of men (N=229) and women (N=104) in North Carolina, we assessed how commonly respondents experienced the dissolution of a primary intimate relationship at the time of their own (among men) or their partner’s (among women) incarceration, and we measured the association between dissolution of relationships during incarceration and STI/HIV-related risk behaviors.

Results

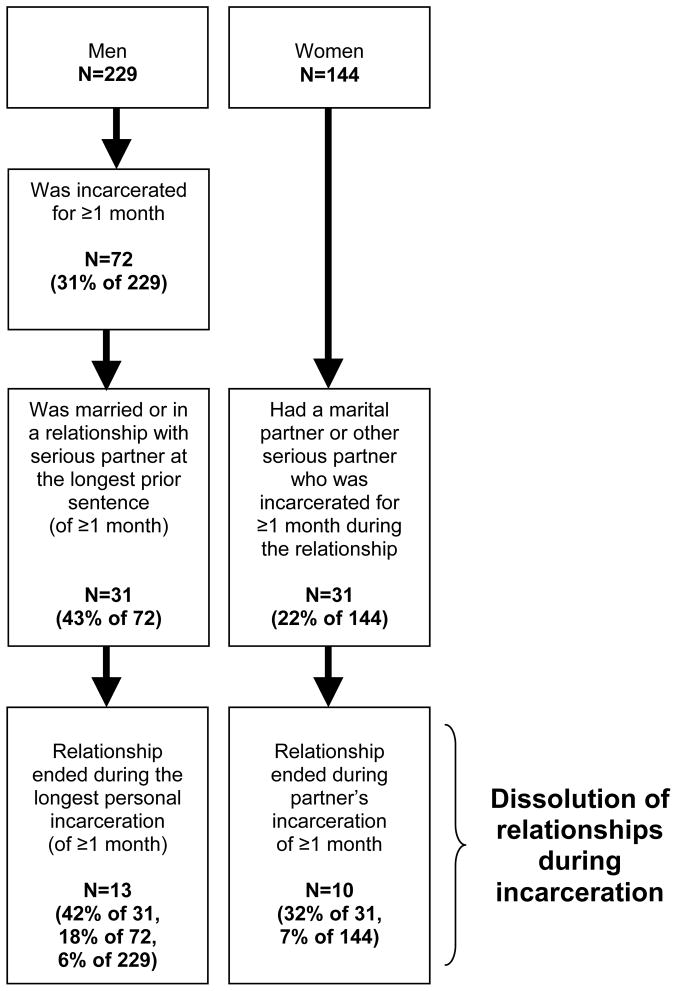

Among men who had ever been incarcerated for one month or longer (N=72), 43% (N=31) had a marital or non-marital primary partner at the time of the longest prior sentence. Among women, 22% (N=31) had ever had a primary partner who had been incarcerated for one month or longer. Of men and women who were in a relationship at the time of a prior incarceration of one month or longer (N=62), 40% reported the relationship ended during the incarceration. In analyses adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and crack/cocaine use, loss of a partner during incarceration was associated with nearly three times the prevalence of having two or more new partners in the four weeks prior to the survey (prevalence ratio: 2.80, 95% confidence interval: 1.13–6.96).

Conclusions

These findings indicated that incarceration disrupts substantial proportions of primary relationships and that the dissolution of relationships during incarceration is associated with subsequent STI/HIV risk. The results highlight the need for further research into the effects of incarceration on relationships and health.

Keywords: incarceration, disruption, sexual risk behavior, STI/HIV, North Carolina

INTRODUCTION

Incarceration is strongly associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In 2004, prison inmates were three to five times more likely to be HIV-infected than those in the United States (US) general population.1,2 Having a partner with a history of incarceration is also an HIV risk factor.3 Not surprisingly, both a history of incarceration and having a recent sexual partner who was incarcerated have been associated with high-risk sexual partnerships including multiple partnerships, concurrent sexual partnerships, and sex trade.4–8 The factors driving STI/HIV risk behavior among former inmates remain unclear and merit further study.

Incarceration may contribute to STI/HIV-related sexual risk behaviors and drug use among former male inmates because incarceration is a disruptive life event that fractures social ties including stable intimate relationships.9–13 Primary partnerships are protective against multiple and concurrent partnerships,14,15 important determinants of STI/HIV infection. Hence, dissolution of primary relationships at the time of incarceration may contribute to high-risk partnerships among prisoners and/or their partners. During the incarceration, the prisoner’s partner may seek other partners to fill an emotional or financial void.11 Newly-released prisoners may seek new and multiple partnerships if there is no longer a partner waiting upon his or her release.16 Research documenting the prevalence of the dissolution of primary relationships at the time of incarceration is limited. Given that incarceration is highly prevalent in many US communities, studying the potential unintended effects of incarceration on relationships and STI/HIV risk is a subject of considerable significance.

We investigated disruption of primary relationships at the time of incarceration in a community-based sample in North Carolina (NC), a state with high HIV incidence.17 A research team including representatives of the local Department of Health, local nongovernmental organizations, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) Carolina Population Center and Center for AIDS Research implemented the NC Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts (NC PLACE) Study in a moderately-sized city affected by relatively elevated levels of STI/HIV, substance abuse, crime, poverty, and incarceration. The primary purpose of the NC PLACE Study was to identify venues where people in the study area go to meet sexual partners, including venues where ex-offenders socialized, and to interview individuals socializing at a sample of venues about their sexual partnerships and sexual risk behaviors. The purpose of this study was to examine how commonly respondents in the community sample experienced the dissolution of a primary intimate relationship at the time of their own or their partner’s incarceration and to measure the association between dissolution of a relationship during incarceration and current STI/HIV-related risk behaviors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and Procedures

We conducted the NC PLACE Study from August through October 2005 using methods we have described in detail previously.18 Briefly, field work was implemented in three phases. In the first phase, we interviewed community informants aged 18 years or older assumed to be knowledgeable about the area (N=120 informants) to identify a list of public social venues where people meet new sexual partners in the study city. In the second phase, we visited each venue identified by community informants (N=146 venues) to verify the venue address and interview a venue representative aged 18 years or older about activities at the site and the potential for on-site HIV/AIDS intervention. We eliminated venues from the venue list if they could not be located (N=3 of 146) or if the venue representative requested that no further interviewing take place at their venue (N=12 of 146). In the final phase, we administered a structured face-to-face sexual behavior survey to individuals of unknown-HIV status socializing at a random sample of the verified social venues (N=54 of 131 venues). The number of social interviews attempted per venue was based on venue size, estimated by the venue representative as the number of men and women who socialized daily at his or her venue. Interviewers attempted to recruit a ratio of two men to one woman, as data obtained from venue representatives indicated that men comprised a higher proportion of the venue population than women.

To select a representative sample of individuals socializing at each venue, a protocol was followed that distributed interviewers systematically throughout the venue to minimize interviewer discretion in selecting respondents by convenience. Interviewers brought the respondents to a private area to protect confidentiality and, after confirming that respondents were at least 18 years old and sober, obtained verbal informed consent for an anonymous 15 to 20 minute interview.

The UNC-CH School of Public Health Institutional Review Board and the Human Subjects Committee at the NC Department of Corrections provided ethical approval for the study.

Measures

Dissolution of a Relationship during Incarceration

Since national estimates indicated that men are much more likely than women to experience incarceration,19 we asked men to report on their own incarceration history and women to report on incarceration of a sexual partner. We asked men who had ever been incarcerated to report the length of the longest jail/prison sentence they had served and to respond to the following question: “When you went to serve this … sentence, were you in a serious relationship, such as with a wife or another serious partner?” Among men in a relationship at the time of the longest prior sentence, we asked, “Did the relationship with this serious partner end permanently during the time you were serving this … sentence?” Among men who had ever been incarcerated for one month or longer and who were in a relationship at the time of the longest prior incarceration, we examined dissolution of the relationship during the longest prior incarceration (yes versus no).

Among all women we asked “Have you ever been in a serious relationship with a partner, such as with a husband or another serious partner, where the partner went to jail/prison for one month or longer during the relationship?” Among women with a primary partner who was incarcerated for one month or longer we asked, “Did you ever have a relationship, such as with a husband or another serious partner that ended permanently when he went to jail or prison?” Among women who had ever had a primary partner who was incarcerated for one month or longer, we examined dissolution of a relationship during a prior incarceration (yes versus no).

Sexual Risk Behaviors

We examined two dichotomous outcomes. We defined multiple partnerships as report of having at least two new sexual partners in the past four weeks. We defined transactional sex as report of having given or received money, goods, or services for sex in the past four weeks.

Data Analysis

We performed analyses in Stata, version 10.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX). We calculated frequencies and/or means of socio-demographic, substance use, and behavioral variables; prior history of being in a relationship when the respondent or his/her partner was incarcerated; and loss of a partner during incarceration.

Among respondents who were in a primary intimate relationship at the time of a prior incarceration (i.e., men who had been in a relationship at the time of their longest prior incarceration among those who had ever been incarcerated for one month or longer and women who had ever had a partner who was incarcerated for one month or longer), we estimated unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between dissolution of a relationship during incarceration and sexual risk behaviors using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering by the venue where the individual was interviewed.20 We specified a log link, a Poisson distribution, an exchangeable correlation matrix structure, and a robust variance estimator to correct for overestimation of the error term resulting from use of Poisson regression with binomial data. 21–23 For each analysis, we tested a product-interaction term in the crude model to evaluate whether associations between dissolution of a relationship during incarceration and sexual risk behaviors differed significantly by gender (p < 0.15 level). Because no associations differed significantly by gender, we aggregated men and women in all analyses. In adjusted analyses, we included the following variables, each identified as a potential confounding variable based on conceptual models and prior research: age less than 30 years, black race, less than high school education, report of being worried about food in the past 30 days, and respondent use of crack/cocaine in the past 12 months.

RESULTS

Recruitment

At five of the 54 community venues randomly selected from the accessible identified sites, no interviews were completed because the one person at each venue who was available and recruited for the interview refused to participate. At the remaining 49 venues, a total of 144 of 185 eligible women (78%) and 229 of 309 eligible men (74%) agreed to participate in the interview. Of the 78 HIV-positive male inmates recruited for the survey, 64 men (82%) agreed to participate in the interview.

Study Population Characteristics

The mean age among men (33 years) was slightly older than the mean age among women (31 years), though the gender-specific age distributions were similar (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds of the sample was African American. Approximately one-third of men and one-quarter of women had not completed high school. Unemployment was reported by greater than one-third of men and women. Recent worry about food security was common among men (18%) and women (21%). A substantial proportion of participants reported using injection drugs, crack/cocaine, ecstasy, speed, or crystal methamphetamine in the past 12 months (33% men, 20% women), with crack/cocaine use reported by the greatest percentages (31% men, 19% women).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic Characteristics, Substance Use, and Sexual Partnerships among Study Participants (NC PLACE Study, 2005) (N=373).

| Men (N=229) | Women (N=144) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%)* | n | (%)* | |

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18–19 years | 17 | (7.4) | 14 | (9.7) |

| 20–24 years | 52 | (22.7) | 31 | (21.5) |

| 25–29 years | 44 | (19.2) | 29 | (20.1) |

| 30–34 years | 25 | (10.9) | 19 | (13.2) |

| 35–39 years | 31 | (13.5) | 19 | (13.2) |

| 40–44 years | 23 | (10.0) | 16 | (11.1) |

| 45+ years | 37 | (16.2) | 16 | (11.1) |

| Race | ||||

| African American | 154 | (67.3) | 93 | (64.6) |

| White | 53 | (23.1) | 44 | (30.6) |

| Other | 10 | (4.4) | 4 | (2.8) |

| Less than high school education | ||||

| No | 155 | (67.7) | 104 | (72.2) |

| Yes | 74 | (32.3) | 37 | (25.7) |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed full or part time | 142 | (62.0) | 91 | (63.2) |

| Unemployed | 79 | (34.5) | 49 | (34.0) |

| Worried about having enough food for self or family† | ||||

| No | 184 | (80.4) | 109 | (75.7) |

| Yes | 40 | (17.5) | 30 | (20.8) |

| Ever incarcerated for >24 hours | ||||

| No | 125 | (54.6) | 103 | (71.5) |

| Yes | 96 | (41.9) | 41 | (28.5) |

| Ever had a partner who was ever incarcerated for >24 hours | ||||

| No | ---- | ---- | 113 | (78.5) |

| Yes | ---- | ---- | 31 | (21.5) |

| Substance use‡ | ||||

| Used any illicit drugs (injection drugs, crack/cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, ecstasy, or speed) | ||||

| No | 150 | (65.5) | 110 | (76.4) |

| Yes | 75 | (32.8) | 29 | (20.1) |

| Used crack/cocaine | ||||

| No | 157 | (68.6) | 112 | (77.8) |

| Yes | 70 | (30.6) | 27 | (18.8) |

| Sexual Partnerships|| | ||||

| Had at least one new sexual partner | ||||

| No | 63 | (27.5) | 57 | (39.6) |

| Yes | 156 | (68.1) | 77 | (53.5) |

| Transactional sex: Gave or received money for sex | ||||

| No | 185 | (80.8) | 116 | (80.6) |

| Yes | 35 | (15.3) | 25 | (17.4) |

Totals may not sum to 100% due to missing values

Community respondents reported on food insecurity in the past four weeks. Prison respondents reported on food insecurity in the four weeks prior to the start of the current incarceration.

Community respondents reported on substance use in the past 12 months. Prison respondents reported on substance use in the six months prior to the start of the current incarceration.

Six respondents (9.4%) reported ecstasy and of these, two additionally reported using crystal methamphetamine.

Community respondents reported on new sexual partnerships in the past 12 months and transactional sex in the past four weeks. Prison respondents reported on new sexual partnerships and transactional sex in the six months prior to the start of the current incarceration.

Sexual Risk Behaviors

The majority of community-based respondents reported having at least one new sexual partner in the past 12 months (68% men, 54% women) and substantial proportions of participants reported transactional sex in the past four weeks (15% men, 17% women) (Table 1).

Incarceration and Dissolution of Relationships at the Time of Incarceration

Forty-two percent of men (N=96) had ever been incarcerated for longer than 24 hours in their lifetime. Of these, the median duration of the longest prior sentence was 6.5 months (range: less than one month to 84 months). Thirty-one percent (N=72) had ever been incarcerated for one month or longer (Figure 1). Of men who had ever been incarcerated for one month or longer, 43% (N=31) had a marital or non-marital primary partner at the time of their longest prior jail/prison sentence, and of these, 42% reported that the relationship ended during the incarceration.

Figure 1.

Dissolution of Relationships During Incarceration (NC PLACE Study, 2005).

Among all women (N=144), 22% (N=31) ever had a primary partner who had been incarcerated for one month or longer, of whom 32% (N=10) reported that the relationship ended during the incarceration (Figure 1). In addition, 12% (N=18) of women had a partner in the past year who had been incarcerated for one month or longer.

Association between Loss of a Partner during Incarceration and Sexual Risk Behaviors

Among men and women who were in a relationship at the time of a prior incarceration of at least one month of longer (N=62 men and women), those who reported dissolution of a relationship during an incarceration were three times more likely to report having multiple (two or more) new partners in the four weeks prior to the survey than those whose relationship did not end during the incarceration (PR: 3.70, 95% CI: 1.36–10.0) (Table 2). In analyses adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and respondent crack/cocaine use in the past year, relationship dissolution was associated with 2.8 times the prevalence of multiple partnerships (adjusted PR: 2.80, 95% CI: 1.13–6.96).

Table 2.

Prevalence Ratios (PRs) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) for the Associations between Loss of an Intimate Partner during the Respondents or His/Her Partner’s Incarceration and HIV-related Sexual Behaviors the Past 12 Months, Among Those Who Were in a Stable Relationship at the Time of Their Own (among Men) or Their Partner’s (among Women) Prior Incarceration (PLACE Method, 2005) (N=57).*

| ≥2 New Sex Partners in the Past 4 Weeks | Transactional Sex in the Past 4 Weeks | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | % | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | |||||

| Experienced Dissolution of a Relationship During Incarceration | ||||||||||

| No (N=34) | 14.7 | ref | ref | 20.6 | ref | ref | ||||

| Yes (N=23) | 56.5 | 3.70 | 1.36–10.0 | 2.80 | 1.13–6.96 | 43.5 | 2.15 | 1.18–3.92 | 1.30 | 0.61–2.79 |

Of the 62 men and women who were in a stable relationship at the time of their own (men) or their partner’s (women) incarceration, 57 had non-missing values on relationship dissolution status.

Adjusted for age less than 30 years, black race, less than high school education, report of being worried about food in the past 30 days, and respondent use of crack/cocaine in the past 12 months.

Dissolution of a relationship during incarceration was associated with twice the prevalence of giving or receiving sex for money, goods, and services in the past four weeks (PR: 2.15, 95% CI; 1.18–3.92). In adjusted analyses, the PR was 1.30 (95% CI: 0.61–2.79). The change in estimate resulted from adjustment for respondent crack/cocaine use in the past 12 months. In this population, crack/cocaine use was virtually inseparably from the experience of trading sex; crack/cocaine use was reported by 75% of those who engaged in transactional sex in the past 12 months and 16% of those who had not.

DISCUSSION

Among individuals recruited from social venues in the urban NC PLACE Study, incarceration of men was prevalent and clearly disruptive of marital or non-marital primary relationships. Over forty percent of the men who had been incarcerated for one month or longer had been in a main partnership at the time of a prior incarceration and one-fifth of women in the sample had ever had a stable partner who had been incarcerated. Of respondents in a prior partnership that was disrupted by incarceration, approximately 40% reported the partnership ended at the time of the incarceration. Prior research has indicated that incarceration leads to emotional division in partnerships9,11–13,24–27 and can result in partnership dissolution.11,12,28 To our knowledge, this study is the first to measure the prevalence of the dissolution of relationships at the time of incarceration.

Prior studies, including by members of our group, have documented strong associations between incarceration and elevated levels of multiple and concurrent partnerships and sex trade.4,5,8,29,30 If incarceration influences STI/HIV risk, elucidation of the pathways through which incarceration may work to influence STI/HIV risk is needed to best plan interventions that minimize incarceration-related effects on transmission. However, our current understanding of these potential pathways incarceration is limited. This study was conducted to evaluate the hypothesis that the association between incarceration and high-risk partnerships may exist, in part, because incarceration disrupts relationships that protect against STI/HIV-related sexual risk behaviors during incarceration. Prior evidence provides a rationale for why loss of a partner during incarceration may lead to high-risk sexual partnerships among prisoners and their partners. During her partner’s incarceration, the prisoner’s partner may seek other partners to fill an emotional, sexual, or financial void.11 If an inmate loses a partner during his time incarcerated, he may seek new and multiple partners to meet these needs after release.

We found that among those who were in a partnership at the time of their own or their partner’s incarceration, loss of a partner during this incarceration was strongly associated with subsequent elevated levels of multiple new partnerships independent of respondent socio-demographic characteristics and drug use. The results indicate that loss of a partner is correlated with STI/HIV risk and suggest that relationship dissolution may work independently of demographic, adverse socio-economic factors, and drug use to influence multiple partnership formation.

Though relationship dissolution also was associated with elevated levels of transactional sex, this association was strongly confounded by respondent crack/cocaine use. We included crack/cocaine use in the model as a confounding factor because crack/cocaine use appears to be a determinant of relationship dissolution31 and is a factor related to STI/HIV risk behavior in this sample.8 However, it also is possible that relationship dissolution may lead to adverse mental health outcomes and, in turn, self-medication with drugs.32 In this case, crack use would serve as a mediator and hence inclusion of this variable in the model would bias the association between relationship dissolution and sex trade. We hypothesize incarceration-related relationship dissolution works reciprocally with drug use to help drive sex trade in this population. These results document high levels of drug use among those involved in the criminal justice system and disproportionate levels among those reporting transactional sex, and they highlight the need for drug treatment and prevention programs, with sexual risk reduction interventions, for current and former inmates and members of their sexual networks.

These findings highlight a need for further research in larger samples and using longitudinal data to examine the effects of losing a primary partner during incarceration on emotional health and STI/HIV risk of former prisoners and their partners, they also point to the need for qualitative research among prisoners and their partners to better understand the degree to which partnerships are protective against STI/HIV risk and the barriers to maintaining partnerships during incarceration.

An important potential threat the validity of the observed associations between relationship dissolution and STI/HIV risk outcomes is the potential for residual confounding due to the inability to measure and adjust for baseline levels of sexual behavior outcomes and additional key confounding factors, such as mental health disorders that may affect interpersonal relationships (e.g., antisocial personality disorder). Further, the cross-sectional data structure greatly limits our ability to interpret associations between loss of a partner during incarceration and STI/HIV risk, though the limitation is somewhat offset by measuring outcomes that occurred in the month prior to the survey, increasing the likelihood that the exposure, incarceration-related relationship dissolution, preceded the STI/HIV risk outcomes. Other limitations included insufficient data on the timing of the incarceration and loss of the relationship, on the nature of partnerships, and on the reasons that partnerships ended at the time of incarceration, a result of limitations on questionnaire length. Clearly, these data are preliminary in nature and further in-depth research is needed to better understand the role of relationship dissolution in the STI/HIV risk of inmates upon release from incarceration.

If additional research confirms that incarceration contributes to dissolution of primary intimate relationships, jail- and prison-based programs to help prisoners and their partners maintain their relationships may be needed, including programs to facilitate calling and visitation. Programs to help prisoners transition from the prison to the community33,34 could provide released prisoners with skills to rebuild social networks and ties with partners and other family members. Finally, it is also possible that alternatives to incarceration for non-violent offenders should be considered to limit the disruption of families and social ties.

SUMMARY.

This study, conducted in an urban North Carolina sample, indicated that incarceration disrupts substantial proportions of primary relationships, and that incarceration-related relationship dissolution is associated with subsequent STI/HIV risk behavior.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This study was supported by a grant from the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research (9P30A150410) and the National Institute of Drug Abuse via RO1 MH068719-01. Maria Khan was supported as a postdoctoral fellow in the Behavioral Sciences Training in Drug Abuse Research program, sponsored by the National Development and Research Institutes, Inc. (NDRI) and Public Health Solutions with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA07233). The conclusions expressed here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funders.

References

- 1.Maruschak LM. HIV In Prisons, 2001. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2004. pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC CfDCaP. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2005. 2006;17 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, et al. Heterosexually transmitted HIV infection among African Americans in North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006 Apr 15;41(5):616–23. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191382.62070.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, et al. Timing and duration of incarceration and high-risk sexual partnerships among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008 Apr 3; doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manhart LE, Aral SO, Holmes KK, Foxman B. Sex partner concurrency: measurement, prevalence, and correlates among urban 18–39-year-olds. Sex Transm Dis. 2002 Mar;29(3):133–43. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent partnerships among rural African Americans with recently reported heterosexually transmitted HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003 Dec 1;34(4):423–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200312010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004 Mar;14(3):155–60. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. J Urban Health. 2008 Jan;85(1):100–13. doi: 10.1007/s11524-007-9237-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Comfort M, Grinstead O, McCartney K, Bourgois P, Knight K. “You Can’t Do Nothing in This Damn Place”: Sex and Intimacy Among Couples With an Incarcerated Male Partner. The Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(1):3–12. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowenstein A. Coping with Stress: The Case of Prisoner’s Wives. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46(3):699–708. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Browning S, Miller S, Lisa M. Criminal Incarceration Dividing the Ties That Bind: Black Men and Their Families. Journal of African American Men. 2001;6(1):87–102. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rindfuss R, Stephen EH. Marital noncohabitation: separation does not make the heart grow fonder. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52(1):259–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneller D. Prisoner’s Families: A Study of Some Social and Psychological Effects of Incarceration on the Families of Negro Prisoners. Criminology. 1975;12(4):402–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Bonas DM, Martinson FE, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR. Concurrent sexual partnerships among women in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002 May;13(3):320–7. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty I. Concurrent sexual partnership among men in the US. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2230–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacGowan RJ, Margolis A, Gaiter J, et al. Predictors of risky sex of young men after release from prison. Int J STD AIDS. 2003 Aug;14(8):519–23. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCDHHS NCDoHHS. N. C . HIV/STD Surveillance Report 2006. Raleigh, NC: Epidemiology Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health & Human Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weir SS, Pailman C, Mahlalela X, Coetzee N, Meidany F, Boerma JT. People to places: focusing AIDS prevention efforts where it matters most. AIDS. 2003;17(6):895–903. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000050809.06065.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.BJS BoJSB. Prison and Jail Inmates at 2003. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986 Mar;42(1):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003 May 15;157(10):940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zocchetti C, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA. Estimation of prevalence rate ratios from cross-sectional data. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1995;24:1064–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.5.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lowenstein A. Coping with Stress: The Case of Prisoner’s Wives. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;46(3):699–708. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Comfort M. ‘Papa’s house’: the prison as domestic and social satellite. Ethnography. 2002;3(4):467–99. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore J. Justice VIo. The Unintended Consequences of Incarceration. New York: Vera Institute of Justice; 1996. Bearing the burden: how incarceration weakens inner-city communities. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adimora AA, Schoenbach V. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;191:S115–22. doi: 10.1086/425280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visher C, La Vigne NG, Travis J. Maryland Pilot Study: Findings from Baltimore. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Justice Policy Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epperson M, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Orellana ER, Chang M. Increased HIV Risk Associated with Criminal Justice Involvement among Men on Methadone. AIDS Behav. 2008 Jan;12(1):51–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9298-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tyndall MW, Patrick D, Spittal P, Li K, O’Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Risky sexual behaviours among injection drugs users with high HIV prevalence: implications for STD control. Sex Transm Infect. 2002 Apr;78( Suppl 1):i170–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behrend L, Khan M, White BL, Wohl DA. Society for Prevention Research. Washington, DC: 2009. Dissolution of stable intimate partnerships during incarceration: implications for HIV transmission. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001 Sep;78(3):458–67. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaller ND, Holmes L, Dyl AC, et al. Linkage to treatment and supportive services among HIV-positive ex-offenders in Project Bridge. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008 May;19(2):522–31. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wohl DA. Personal communication, results based on analysis of the BRIGHT pilot study dataset. 2005.