Abstract

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) is active only as a homodimer. Recent data has demonstrated that exogenous NO can act as an inhibitor of eNOS activity both in intact animals and vascular endothelial cells. However, the exact mechanism by which NO exerts its inhibitory action is unclear. Our initial experiments in bovine aortic endothelial cells indicated that exogenous NO decreased NOS activity with an associated decrease in eNOS dimer levels. We then undertook a series of studies to investigate the mechanism of dimer disruption. Exposure of purified human eNOS protein to NO donors or calcium-mediated activation of the enzyme resulted in a shift in eNOS from a predominantly dimeric to a predominantly monomeric enzyme. Further studies indicated that endogenous NOS activity or NO exposure caused S-nitrosylation of eNOS and that the presence of the thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase system could significantly protect eNOS dimer levels and prevent the resultant monomerization and loss of activity. Further, exogenous NO treatment caused zinc tetrathiolate cluster destruction at the dimer interface. To further determine whether S-nitrosylation within this region could explain the effect of NO on eNOS, we purified a C99A eNOS mutant enzyme lacking the tetrathiolate cluster and analyzed its oligomeric state. This enzyme was predominantly monomeric, implicating a role for the tetrathiolate cluster in dimer maintenance and stability. Therefore, this study links the inhibitory action of NO with the destruction of zinc tetrathiolate cluster at the dimeric interface through S-nitrosylation of the cysteine residues.

Nitric oxide (NO) is produced from l-arginine and oxygen by nitric oxide synthases (NOS) (EC. 1.14.13.39) (1). Three isoforms of NOS are known. Constitutive forms are present in endothelial cells [endothelial NOS (eNOS)] and neurons (neuronal NOS), and a third inducible isoform is present in macrophages (inducible NOS) (2–4). Dimerization is an absolute requirement for catalytic activity in all three NOS isoforms (5–7). NOS isoforms have two domains, the N-terminal oxygenase domain and the C-terminal reductase domain. The oxygenase domain has the binding site for tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), heme, and the substrate l-arginine and the reductase domain binds FAD, FMN, and NADPH. NO is produced in the oxygenase domain by the oxidation of arginine in a two-step reaction that generates l-citrulline and NO (8, 9).

Our previous studies indicate that exogenous NO exposure inhibits eNOS activity (10, 11). However, the mechanism for the inhibition remains unclear. NO gas and NO donors have the potential to induce S-nitrosylation of proteins (12). We hypothesized that the inhibitory action on NO on eNOS could be acting by means of S-nitrosylation, with a resultant alteration in eNOS dimeric structure and activity. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the nitrosylating effect of endogenous and exogenous NO on eNOS oligomeric state and catalytic activity. Enzyme activation or the addition of exogenous NO produced an inhibitory effect on the ability of eNOS to metabolize l-arginine, and this inhibitory action was demonstrated to be associated with the loss of eNOS dimers. This loss of dimer could be reversed in the presence of thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system, suggesting an important role for cysteine residues. To determine the importance of tetrathiolate cysteine at the dimer interface, we analyzed the C99A mutant enzyme for its oligomeric state. This mutant was predominantly monomeric, suggesting the role of tetrathiolate in dimer stability. This study implicates cysteine residues in the eNOS protein as being particularly important for both dimer stability and enzyme activity. Furthermore, we suggest an inhibitory action of NO involving the S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues, leading to a shift in eNOS to a predominantly monomeric form with a resultant loss of enzyme activity.

Methods

Chemicals. Spermine NONOate (SPERNO) was from R & D Systems. Calmodulin Sepharose, ADP-Sepharose, and l-[2,3,4,5-3H]arginine were from Amersham PharmaciaPharmacia. The antibody against eNOS was from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY) and the antibody against S-nitrosylation from Calbiochem. LB broth and Scintiverse II were from Fisher. isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside was from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid resin and BL21 (DE3) pLysS were from Novagen. Western blotting reagents were from Pierce. Disposable minicolumns, Chelex-100, and Bradford reagent for protein determination were from Bio-Rad. All other chemicals were from Sigma. The polyHis-pCWeNOS vector was a gift from P. R. Ortiz de Montellano (University of California, San Francisco). The C99A mutant was made commercially (Retrogen, San Diego) from the polyHis-pCWeNOS vector.

Cell Culture. Primary cultures of bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAECs) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego). BAECs were cultured as we have described (13). For all experiments, cells were incubated overnight in serum-free DMEM with 1 g/liter glucose. Cells were treated for 60 min with the NO donor. Cells were harvested into PBS, sonicated, and then used without further purification to measure NOS activity and eNOS dimer levels. Protein concentration was determined by using the Bradford assay.

Expression and Purification of Wild-Type and Mutant (C99A) eNOS.

The polyHis-pCWeNOS vector and the mutant C99A eNOS plasmid were introduced into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) pLysS. Cells were cultured as described (14). Cells were then harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer as described (15), and were incubated with mild shaking at 4°C for 30 min to ensure complete cell lysis. Cells were then broken by sonication and debris were removed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was then applied to a Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid His-Bind Superflow column that was preequilibrated with Buffer A [40 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid, pH 7.6], containing 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.5 mM l-arginine. The column was washed with 5 bed volumes of buffer A followed by Buffer B (Buffer A with 25 mM imidazole). The bound protein was then eluted with Buffer C (Buffer A with 200 mM imidazole). The heme-containing fractions were pooled and were concentrated by using centriprep-100 YM-10 (Millipore). The concentrated protein were dialyzed against three changes of Buffer A containing 4 μM BH4 and 1 mM DTT. The proteins were further purified by using a 2′5′-ADP-Sepharose column equilibrated with 40 mM Tris·HCl buffer, pH 7.6, containing 1 mM l-arginine, 3 mM DTT, 4 μM BH4, 4 μM FAD, 10% glycerol, and 150 mM NaCl (Buffer D), and washed with buffer D containing 400 mM NaCl to prevent nonspecific binding. eNOS was then eluted with Buffer E (Buffer D with 5 mM 2′AMP). The heme-containing fractions were pooled, were concentrated, and were dialyzed at 4°C against buffer D containing 1 mM DTT, 4 μM BH4, 4 μM FAD, and 10% glycerol, and was stored at -80°C until used. DTT, BH4, and FAD were removed by repeated buffer exchange as required.

Assays for the Effects of Endogenous and Exogenous NO on Purified Recombinant eNOS. Fractions of DTT-free purified eNOS (2 μg) were incubated in the reaction mixture for the citrulline conversion assay in the presence and absence of SPERNO (100 μM), thioredoxin (5 μM)/thioredoxin reductase (6.4 μM) system, or the NOS inhibitor, l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (1 mM), for 0–60 min at 37°C and eNOS activity was determined. The eNOS dimer and S-nitrosylation levels were then determined by using either low-temperature PAGE (LT-PAGE) and Western blot analysis (16) or gel filtration analysis (for eNOS dimer levels) or Western blotting (S-nitrosylation).

Assay for NOS Activity. This assay was performed by measuring the formation of [3H]citrulline from [3H]arginine (19) containing 10 μM l-arginine as substrate as published by our laboratory (10).

Gel Filtration Chromatography. Gel filtration chromatography was carried out at 4°C by using a Superose 6 HR10/30 column and an FPLC system (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). The column was equilibrated with 40 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid buffer, pH 7.6/5% glycerol/0.5 mM DTT/150 mM NaCl. Typically pure eNOS protein (100 μg) in 200-μl sample volume was injected and the column effluent was monitored at 280 nm by using a flow-through UV detector. The column was calibrated with standard gel filtration molecular weight standards.

Optical Absorption Spectroscopy. Optical spectra were recorded on a Shimadzu Biospec 1601 spectrophotometer at 22°C. The spectra of pure NOS were recorded in cuvettes containing 3–5 μM eNOS protein in 40 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid buffer, pH 7.6 with 0.1 mM DTT and 10% glycerol in a final volume of 1 ml. eNOS was treated with SPERNO (100 μM) and incubated at 37°C for 30min before spectra recorded between 350–700 nm.

Detection of S-Nitrosothiols. The presence of nitrosothiols was detected with the spectral assay method of Jaffrey et al. 2001 (17). Briefly, DTT-free eNOS protein (500 μg) was treated with 1 mM of S-nitroso-acetyl penicillamine by incubating at 37°C for 1 h in the dark. The S-nitroso-acetyl penicillamine was then removed by passing through a spin column, and the presence of nitrosothiol bond was analyzed by observing the spectral absorption scan between 300–400 nm. As a control, the eNOS protein was treated with 1 mM N-acetyl penicillamine. The presence of S-nitrosothiols was also confirmed by using the Saville–Griess assay (18).

Zinc Release by 4(2-Pyridylazo Resorcinol) (PAR) Assay. The zinc release has been measured by PAR assay, as described by Crow et al. (20) with some modification. The dye PAR, which is yellow in color, has a low absorbance at 500 nm. However, after chelating to zinc, the PAR–Zn complex becomes orange in color and has an increased absorbance at 500 nm. All of the buffers were pretreated with Chelex-100 to remove residual zinc. The eNOS enzyme was also purified in buffers treated with Chelex-100. DTT-free purified eNOS protein (assay 1–1.5 mg) was treated with SPERNO (100 μM) for 30 min in a reaction volume of 200 μl at room temperature in the dark. The reaction mixture was added to a cuvette containing 150 μM PAR in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8, in a total volume of 1 ml. This solution was mixed well and the spectra were recorded between 300 to 600 nm. eNOS protein alone was used to calibrate the spectrophotometer.

Statistical Analysis. All band intensities were then quantitated by densitometric scanning with a Kodak image station with the ksd1d software purchased from DuPont-NEN (Boston). The means ± SD were calculated. Comparisons between treatment groups were made by the unpaired t test with the gb-stat software program. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

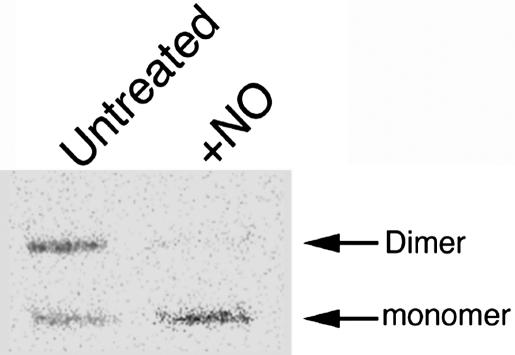

Effect of Exogenous NO Treatment on eNOS Activity in BAECs. To investigate the in vivo effect of NO on eNOS activity, BAECs were treated for 60 min with 500 μM SPERNO. The results obtained indicated that exogenous NO produced a significant decrease in NOS activity (92 ± 4%, P < 0.05 vs. untreated). We then investigated the effect of exogenous NO on eNOS dimer levels by LT-PAGE and Western blot analysis (Fig. 1) and found that there was a significant reduction in dimeric eNOS (82 ± 8%, P < 0.05 vs. untreated) and a concomitant increase in the inactive monomer form. Similar results were obtained with other NO donors diethylamine nitric oxide and 2,2′-(hydroxynitroso-hydrazino)bis-ethamine (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Effect of exogenous NO on eNOS in BAECs. BAECs were treated (+) or untreated (-) with SPERNO (100 μM) for 1 h, then eNOS dimer levels were determined. Protein extracts (20 μg) were subjected to LT-PAGE and Western blot analyses. A representative Western blot is shown from n = 4.

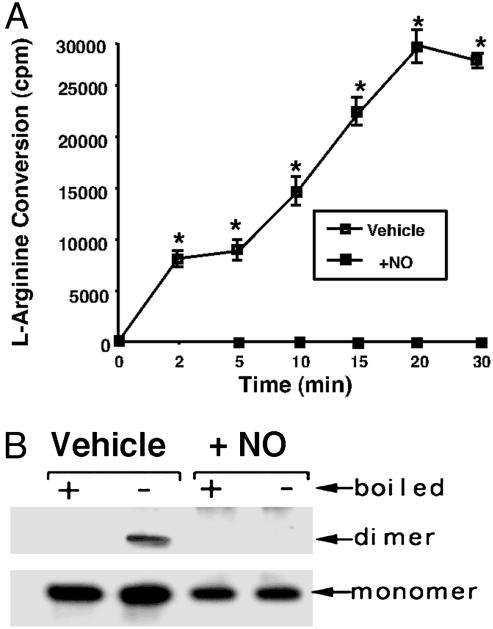

Effect of Exogenous NO on Purified Human eNOS. To further investigate the mechanism by which NO alters the eNOS oligomeric state, we used an expression purification system based in E. coli. We exposed purified DTT-free eNOS (2 μg) to the NO donor SPERNO to determine its effect on the ability of the enzyme to metabolize l-arginine. The results obtained indicated that although the vehicle-treated protein possessed the ability to metabolize l-[3H]arginine to form l-[3H]citrulline, the presence of the NO donor SPERNO (100 μM) completely inhibited the enzyme (Fig. 2A), indicating that we could mimic the in vivo effect of NO in vitro. Similarly, the presence of SPERNO significantly reduced the level of dimeric eNOS (Fig. 2B). Quantitation of the levels of eNOS dimer in the LT-PAGE analysis indicate that dimer levels were reduced from 54 ± 8% in the vehicle-exposed protein to 8 ± 6% in the protein exposed to SPERNO (P < 0.05 vehicle vs. SPERNO).

Fig. 2.

NO-mediated inactivation of purified human eNOS. (A) Purified human eNOS protein (2 μg) was tested for its ability to metabolize [2,3,4,5-3H]-larginine in the presence (+NO) or absence (vehicle) of the NO donor SPERNO (100 μM). The presence of the NO donor results in the total inhibition of the recombinant eNOS protein. *, P < 0.05 vs. SPERNO. (B) Purified human eNOS (400 ng) was exposed (30 min at 37°C) to the NO donor SPERNO (100 μM, + NO), was subjected to LT-PAGE and Western blot analyses, and was compared with eNOS protein exposed only to sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (vehicle). +, eNOS protein exposed to 95°C for 5 min before loading to monomerize all eNOS protein; -, eNOS protein not boiled before loading. A representative Western blot is shown from n = 4.

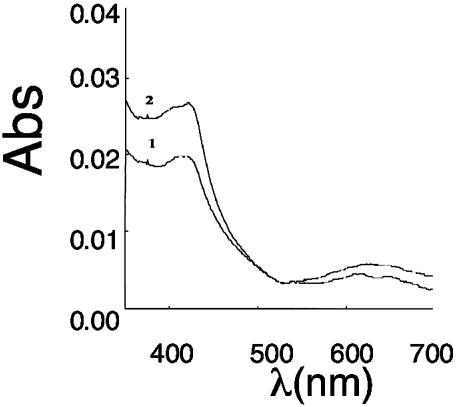

NO can bind to the heme ring of eNOS. To determine whether heme binding could induce the dimer-to-monomer shift, we exposed purified eNOS to methylene blue (10 μM) and potassium cyanide (10 mM) to oxidize the heme ring. The results obtained indicate no significant effect on eNOS dimer levels (62 ± 8% for vehicle and 58 ± 9% for methylene blue-treated). Thus, NO binding to the heme ring does not appear to be involved in dimer disruption. In addition, NO did not appear to cause heme loss from the enzyme, because the optical absorption spectroscopy data indicated heme remained bound to the enzyme, although in a completely oxidized form (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Light absorbance spectra of purified eNOS before and after NO treatment. Curve 1, eNOS (10 μM) in 40 mM EPPS with10% glycerol and 0.1 mM DTT. Initially, a mixture of ferric and ferrous peaks is observed, however, after 2 min, there is complete oxidation to ferric heme with absorbance maxima at ≈420. Curve 2, spectra of the above eNOS mixture with 100 μM SPERNO incubated at 37°C for 30 min showing no loss of heme.

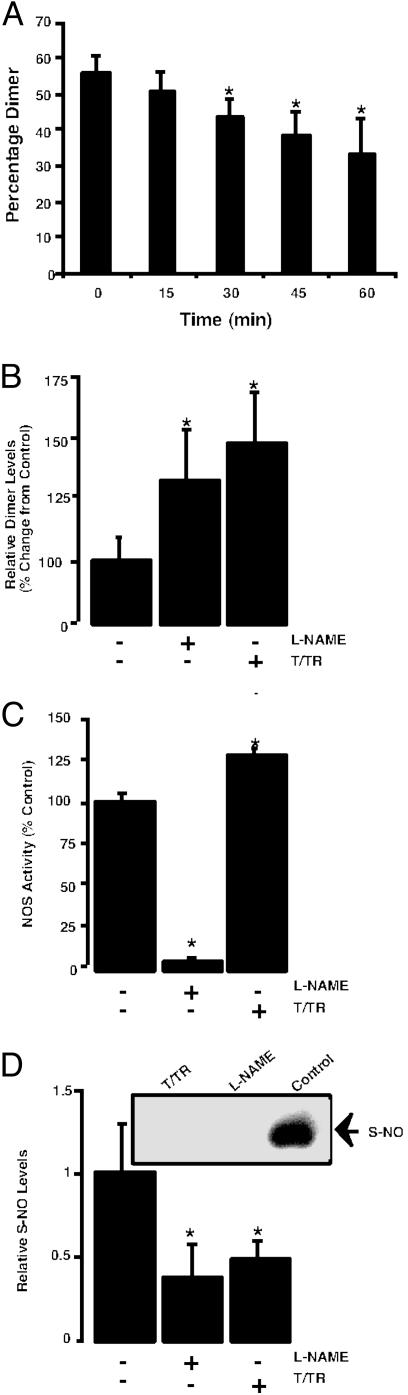

To examine the potential autoinhibitory effect of NO in an in vitro condition, we incubated purified eNOS in the presence of all necessary cofactors with excess substrate l-arginine and analyzed the oligomeric state of the enzyme over time. We found that there was a time-dependent degradation of the dimer (Fig. 4A). This dimer degradation was prevented by NOS inhibitor l-NAME (100 μM) or the disulfide reductase system (Fig. 4B), suggesting the dimer-degradative effect was due to the self-generated NO. In addition, the presence of the disulfide reductase system significantly increased the ability of eNOS to metabolize l-arginine (Fig. 4C) and this occurrence was associated with a significant decrease in the level of S-nitrosylated eNOS protein (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Calcium-dependent activation of eNOS produces a decrease in dimer levels and increases S-nitrosylation. (A) Densitometric analysis of LT-PAGE of activated eNOS (2 μg) showing time-dependent decreases in dimer levels. Western blot analysis of activated eNOS in the presence of all of the cofactors and excess substrate (0–60 min). Activation of eNOS results in degradation of dimeric. (n = 3.) *, < 0.05 vs. T = 0 min. (B) The decrease in NOS dimer levels is reduced by the NOS inhibitor l-NAME or the disulfide reductase system (T/TR). (n = 5.) *, < 0.05 vs. control. (C) The presence of the disulfide reeducates system (T/TR) increases the activity of the eNOS enzyme. (n = 4.) *, < 0.05 vs. control. (D) The calcium-dependent activation of eNOS increases the S-nitrosylation of the enzyme that is inhibited by l-NAME or the disulfide reeducates system (T/TR). (Inset) A representative image from n = 3. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

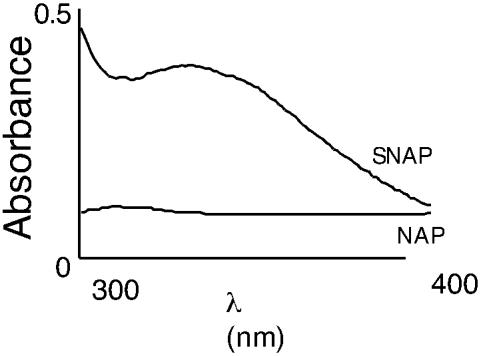

We then determined the effect of exogenous NO on eNOS S-nitrosylation. Spectroscopic analysis of NO-treated enzyme identified a maximum absorbance at ≈320 nm, indicating the presence of a nitrosothiol bond (Fig. 5A). To confirm the presence of the S-nitrosothiol group, we performed the Saville assay. The results obtained indicated that there was a time-dependent increase in S-nitrosothiol residues in eNOS, compared with vehicle-treated eNOS (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

NO induces S-nitrosylation of recombinant human eNOS. DTT-free human eNOS protein (500 μg) was exposed to S-nitroso-acetyl penicillamine (SNAP) (1 mM) for 1 h at 37°C in the dark. The nitrosylating reagent was removed by using a spin column, and a spectral scan was carried out in the range of 300–400 nm. As a control, the human eNOS protein was treated with the non-NO releasing agent, N-acetyl penicillamine (NAP) (1 mM).

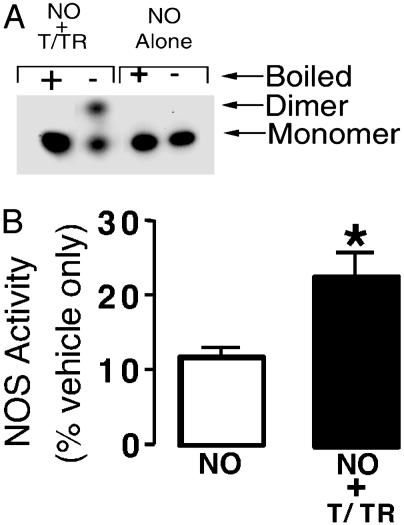

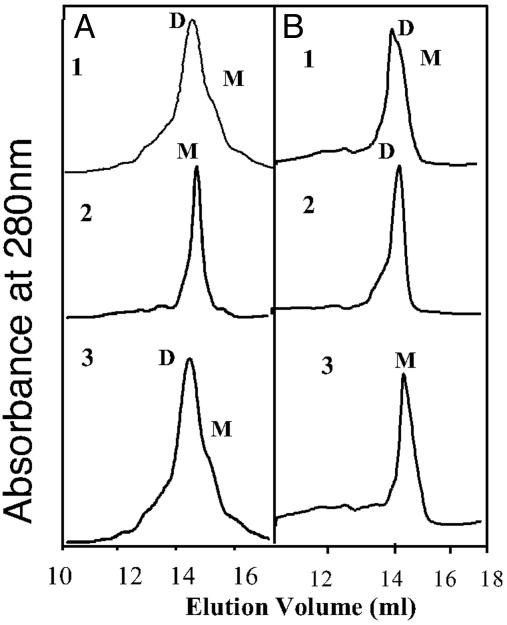

We next determined the dimer disruption of eNOS was caused by NO-mediated interactions with cysteine residues. Purified eNOS protein was exposed to NO in the presence of the disulfide reductase system. In the presence of the disulfide reductase system, we found that the NO-induced disruption of eNOS dimers was significantly reduced, as determined by LT-PAGE and Western blot analyses (Fig. 6A). In addition, the inhibitory effect of NO on eNOS metabolism of l-[3H]arginine to l-[3H]citrulline was also reduced, although activity was not returned to levels obtained by using vehicle-treated eNOS alone (Fig. 6B). To further confirm these effects, we used gel filtration analyses (Fig. 7 A1 and A2). When eNOS was treated with the NO donor in the presence of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase system, although there was some monomerization, eNOS remained predominantly in a dimeric state (Fig. 7B1). eNOS could be maintained in a completely dimeric state after increasing the concentration of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase system (Fig. 7B2). Furthermore, we demonstrated that this protection of eNOS dimer was enzymatic, because the assay carried out in the absence of thioredoxin reductase did not maintain eNOS in a dimeric form (Fig. 7B3). Also, in the presence of the reducing agent DTT (5 mM), the NO-mediated monomer shift was prevented (Fig. 7A3). However, low concentration of DTT (up to 1 mM) did not prevent exogenous NO-mediated monomerization (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

The presence of the disulfide reductase system protects the human eNOS dimer from the effects of NO. (A) Purified human eNOS (400 ng) was exposed, for 30 min at 37°C, to the NO donor SPERNO (100 μM), either alone (NO alone) or after a preincubation with thioredoxin (5 μM) and thioredoxin reductase (6.4 μM) in the presence of 0.2 mM NADPH (NO + T/TR). Each fraction was then subjected to LT-PAGE and Western blot analyses. +, eNOS protein exposed to 95°C for 5 min before loading to monomerize all eNOS protein; -, eNOS protein not boiled before loading. (B). Assays were carried out with purified eNOS (2 μg) to determine the effect of preincubation with thioredoxin (5 μM), thioredoxin reductase (6.4 μM), and 0.2 mM NADPH on the ability of eNOS to metabolize [2,3,4,5-3H]-l-arginine (30 min at 37°C). Values are expressed as a percentage of the mean ± SD of that obtained from eNOS exposed to vehicle only (sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 100%). *, P < 0.05 vs. SPERNO alone.

Fig. 7.

Gel filtration analyses of purified human eNOS from E. coli. (A and B) Human eNOS (200 μg) was subjected to gel filtration analysis in the presence (A1) or absence (A2) of SPERNO (100 μM) for 30 min at 37° and with DTT (5 mM) (A3), thioredoxin (5 μM), and thioredoxin reductase (6.5 μM) and 0.2 mM NADPH (B1), thioredoxin (15 μM), and thioredoxin reductase (19.5 μM) and NADPH (0.6 mM) (B2), or thioredoxin (5 μM) and 0.2 mM NADPH without thioredoxin reductase (B3). NO alone reduces the level of dimeric eNOS, and this effect is dose-dependently diminished in the presence of thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase and NADPH but not in the absence of thioredoxin reductase. DTT at 5 mM prevents the exogenous NO-induced monomerization (A3). Shown are representative gel filtration analyses from three independent experiments.

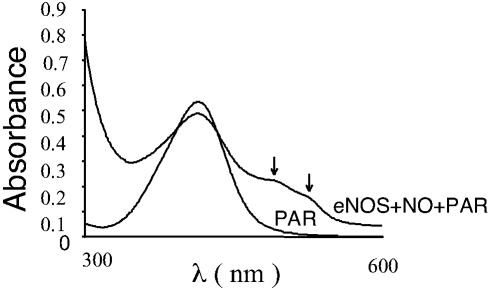

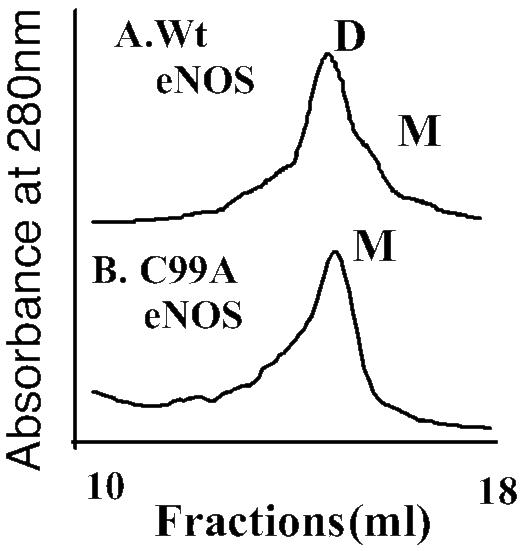

Zinc Release and Monomerization. To determine the molecular mechanisms for dimer disruption, we analyzed the effect of NO on the integrity of the zinc tetrathiolate cluster at the dimer interface by using the PAR assay. Our results indicated that there was a release of zinc when eNOS was exposed to NO, as determined by the increase in absorbance of PAR-bound zinc at 500 nm (Fig. 8). These data suggest that NO can destroy the zinc tetrathiolate bond at the dimer interface. To further examine the importance of tetrathiolate cluster in eNOS dimer stability, we purified the C99A mutant enzyme and analyzed its oligomeric state by gel filtration assay. The results obtained demonstrated that the mutant enzyme is a mixture of dimer and monomer, but after a freeze–thaw cycle, the mutant enzyme becomes predominantly monomeric, compared with wild type (Fig. 9). Together, these results indicate that the mechanism by which NO induces the dimer monomer shift involves, at least in part, cysteine thiol nitrosylation within the zinc tetrathiolate cluster located at the dimer interface.

Fig. 8.

Zn release assay. Purified human eNOS (1 mg) was treated with SPERNO (100 μM) for 30 min at 37°C in a cuvette containing PAR (150 μM). A cuvette containing only eNOS was used to autozero the spectrophotometer. After mixing well, absorbance spectra was recorded between 300–600 nm. Shown is a representative recording from three independent experiments.

Fig. 9.

Gel filtration analyses of purified wild-type and C99A mutant eNOS enzyme. Human eNOS (200 μg) or the C99A mutant eNOS protein (200 μg) was subjected to gel filtration analyses. Under identical purification conditions, the eNOS protein is a mixture of both monomers and dimers, but the C99A mutant protein is exclusively monomeric after a freeze–thaw cycle. Shown are representative gel filtration analyses from three independent experiments.

Discussion

Our previous studies have shown that inhaled NO (11) or NO-releasing compounds (12) can inhibit eNOS activity. However, the mechanisms associated with this inhibitory effect have not been fully elucidated. It has been suggested that the inhibitory effects of NO may be due to the formation of a tight complex between the NO and the heme moiety (21). However, our studies indicate that another inhibitory interaction of NO with the NOS enzyme occurs at cysteine thiol groups, resulting in dimer disruption and loss of activity. This finding suggests a mechanism for NO-mediated eNOS inhibition in which the sulfhydryl group, located either in the interface of the dimer or the intermolecular disulfides involved in dimer maintenance, are oxidized, leading to dimer disruption. In addition, our data indicating that endogenous NO generation was also sufficient to produce a reduction in eNOS dimer levels associated with increased S-nitrosylation further suggests that this inhibitory mechanism may have biological relevance for eNOS regulation to curtail exuberant NO production in vivo.

NO can react with metal-containing proteins (especially hemeproteins) (22). The affinity of hemeproteins for NO has led to speculation that NOS may be inhibited by the NO produced during catalysis of l-arginine binding to the heme moiety. However our data, in which NO-heme binding was mimicked by using methylene blue, showed no reduction in dimer levels. It should be noted that the two inhibitory mechanisms of NO on NOS may not be mutually exclusive. NO has been demonstrated to inhibit cytochrome P450-catalyzed reactions (23). The binding of NO to enzymes has two phases. The first, a reversible state, is thought to be due to a binding of NO to the heme moiety of the enzyme and the second, an irreversible state, may possibly be caused by the oxidation of critical thiol-containing amino acids within the protein (23). Thus, NO binding to the heme moiety and oxidation of cysteine residues may both be involved in an inhibitory effect of NO. This result may account for the discrepancy in our data investigating eNOS dimer maintenance and NOS activity. We could detect complete protection of the eNOS dimer in the presence of the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system but only partial restoration of enzyme activity. Alternatively, the inability of thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase to fully restore enzyme activity may reflect the incomplete reconstitution of zinc into the thiolate complex.

Our gel filtration data clearly indicate that the eNOS dimer is disrupted by NO, which is prevented in the presence of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase system. This finding indicates the involvement of cysteine residues and a mechanism whereby NO nitrosylates thiol residues, which, as a consequence, displaces BH4 from the protein. This finding would result in dimer becoming increasingly unstable with a resultant loss of activity. Indeed, the spectral analysis of the NO treated eNOS had absorbance maxima at ≈320 nm, indicating the presence of nitrosothiol bond. This conclusion was also supported by the Saville assay in which a time-dependent increase in nitrosylation was observed. In addition, our studies indicated that DTT (5 mM) prevented dimer disruption induced by NO, but at low concentrations of DTT (up to 1 mM), did not prevent this effect. DTT is generally involved in rearrangement of disulfide bonds. It has been demonstrated to help in restoring pterin and substrate binding in E. coli-purified neuronal NOS oxygenase domain over prolonged incubation (24).

Our data also indicate that NO destroys zinc tetrathiolate cluster at the dimer interface with resultant zinc release. Recently, the crystal structure for the heme domain of eNOS and inducible NOS has been solved (25, 26). The crystal structure of eNOS reveals a zinc ion is tetrahedrally coordinated to two pairs of symmetry-related cysteine residues (corresponding to cys94 and cys99 from each monomer), predicted to be at the dimer interface. Now, it is known that all NOS isoforms have tetrathiolate zinc and it confers SDS-resistance, at least in the case of neuronal NOS (27). In proteins, tetrahedral zinc ions with thiolate ligands often stabilize protein structure and participate in catalysis. It has been reported that zinc binding results in net gain of eight hydrogen bonds, which could contribute favorably to the free energy of dimer stabilization, as decrease in negative charge contributes to increased protein stability (25). In neuronal NOS, Reif et al. (28) reported the role of BH4 as a stabilizing factor during catalysis and proposed that BH4 may interfere with enzyme destabilizing products. It has also been suggested that the strong reducing conditions of the cytosol do not favor disulfide formation (29). Thus, NOS may use zinc binding to amplify the conformational stability of the dimer interface. The crystal structure of zinc-free and bound eNOS points to the fact that the zinc is bound equidistant from both BH4 and heme iron atom, highlighting the strategic location and important structural role, which includes maintaining the integrity of the pterin-binding pocket and providing docking surface for the reductase domain (25). The replacement of zinc cysteine residues with other amino acids results in altered pterin or substrate binding (30). Thus, zinc coordination is thought to be important for maintaining the integrity of the BH4-binding site and maintaining the dimeric structure of the enzyme. This conclusion is supported by our gel filtration data by using purified C99A mutant enzyme that lacks the ability to form a tetrathiolate cluster. The C99A mutant enzyme was predominantly monomeric (with some dimeric structure only observed in freshly prepared enzyme), indicating that the mutant enzyme lacking the tetrathiolate cluster is highly unstable. Taken together, these studies suggest that the C94 and C99 residues may contribute in maintaining eNOS dimer integrity and may be susceptible to oxidation through S-nitrosylation. Indeed, NO production has been correlated with zinc release from metalloproteins (31, 32). In addition, Zou et al. (33) have presented evidence for zinc release from eNOS exposed to peroxynitrite, with resultant uncoupling to produce superoxide. We also observed zinc release after NO treatment to eNOS, as demonstrated in a PAR assay with a resultant monomerization. Therefore, we propose that the monomerization of eNOS requires the interplay of number of factors in a multistep process. First, the tetrathiolate may be oxidized, resulting in the formation of a disulfide bond between monomers with concomitant zinc release. This occurrence alters pterin binding, possibly causing its release from the dimer. This result then leads to intramolecular thiol nitrosylation, causing changes in structural conformation to an already unstable enzyme, leading to monomerization. NO itself is not a biologically relevant nitrosylating agent, instead, it is a precursor of higher oxides of nitrogen, including NO2 and N2O3 and peroxynitrites that actually mediate protein S-nitrosylation (34). Although further site-directed mutagenesis and mass spectrometric studies will be required to determine whether the intramolecular cysteine residues, tetrathiolate cysteines, or both, undergo S-nitrosylation to induce dimer collapse.

In conclusion, this study implicates intrasubunit cysteine and the tetrathiolate cysteine residues in eNOS as being important for dimer maintenance and enzyme activity. The loss of the zinc due to the tetrathiolate cluster oxidation by NO at the dimeric interface may lead to altered pterin binding, making the enzyme unstable. This effect in combination with intrasubunit nitrosylation may lead to dimer collapse. Thus, we have identified an inhibitory action of NO involving the oxidation of cysteine residues by means of S-nitrosylation-induced collapse of the eNOS dimer, with a resultant loss of enzyme activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL60190, HL67841, HD39110, HL70061, and HL72123 (to S.M.B.), and American Heart Association, Midwest Affiliates Grant 0051409Z (to S.M.B.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: NOS, NO synthase; eNOS, endothelial NOS; SPERNO, spermine NONOate; BAEC, bovine aortic endothelial cell; LT-PAGE, low-temperature PAGE; l-NAME, l-arginine methyl ester; PAR, 4(2-pyridylazo resorcinol).

References

- 1.Alderton, W. K., Cooper, C. E. & Knowles, R. G. (2001) Biochem. J. 357, 593-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamas, S., Marsden, P. A., Li, G. K., Tempst, P. & Michel, T. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 6348-6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie, Q. W., Cho, H. J., Calaycay, J., Mumford, R. A., Swiderek, K. M., Lee, T. D., Ding, A., Troso, T. & Nathan, C. (1992) Science 256, 225-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredt, D. S., Hwang, P. M., Glatt, C. E., Lowenstein, C., Reed, R. R. & Snyder, S. H. (1991) Nature 351, 714-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh, D. K., Abu-Soud, H. M. & Stuehr, D. J. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 1444-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Crespo, I. & Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. (1996) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 336, 151-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venema, R. C., Ju, H., Zou, R., Ryan, J. W. & Venema, V. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 1276-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marletta, M. A. (1994) Cell 78, 927-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stuehr, D. J. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1411, 217-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black, S. M., Heidersbach, R. S., McMullan, D. M., Bekker, J. M., Johengen, M. J. & Fineman, J. R. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277, H1849-H1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheehy, A. M., Burson, M. A. & Black, S. M. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274, L833-L841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamler, J. S., Lamas, S. & Fang, F. C. (2001) Cell 106, 675-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brennan, L. A., Wedgwood, S., Bekker, J. M. & Black, S. M. (2002) DNA Cell Biol. 21, 827-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez-Crespo, I., Gerber, N. C. & Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 11462-11467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black, S. M. & Ortiz de Montellano, P. R. (1995) DNA Cell Biol. 14, 789-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hallmark, O. G., Phung, Y. T. & Black, S. M. (1999) DNA Cell Biol. 18, 397-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaffrey, S. R., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Ferris, C. D., Tempst, P. & Snyder, S. H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eu, J. P., Liu, L., Zeng, M. & Stamler, J. S. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 1040-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush, P. A., Gonzalez, N. E. & Ignarro, L. J. (1992) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 186, 308-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crow, J. P., Sampson, J. B., Zhuang, Y., Thompson, J. A. & Beckman, J. S. (1997) J. Neurochem. 69, 1936-1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurshman, A. R. & Marletta, M. A. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 5627-5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ignarro, L. J. (1989) Semin. Hematol. 26, 63-76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wink, D. A., Osawa, Y., Darbyshire, J. F., Jones, C. R., Eshenaur, S. C. & Nims, R. W. (1993) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 300, 115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sono, M., Ledbetter, A. P., McMillan, K., Roman, L. J., Shea, T. M., Masters, B. S. & Dawson, J. H. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 15853-15862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raman, C. S., Li, H., Martasek, P., Kral, V., Masters, B. S. & Poulos, T. L. (1998) Cell 95, 939-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, H., Raman, C. S., Glaser, C. B., Blasko, E., Young, T. A., Parkinson, J. F., Whitlow, M. & Poulos, T. L. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21276-21284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemmens, B., Goessler, W., Schmidt, K. & Mayer, B. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35786-35791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reif, A., Frohlich, L. G., Kotsonis, P., Frey, A., Bommel, H. M., Wink, D. A., Pfleiderer, W. & Schmidt, H. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 24921-24929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwabe, J. W. & Klug, A. (1994) Nat. Struct. Biol 1, 345-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, P. F., Tsai, A. L. & Wu, K. K. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 215, 1119-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berendji, D., Kolb-Bachofen, V., Meyer, K. L., Grapenthin, O., Weber, H., Wahn, V. & Kroncke, K. D. (1997) FEBS Lett. 405, 37-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroncke, K. D. & Kolb-Bachofen, V. (1999) Methods Enzymol. 301, 126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou, M. H., Shi, C. & Cohen, R. A. (2002) J. Clin. Invest. 109, 817-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lane, P., Hao, G. & Gross, S. (2001) Sci STKE 86, RE1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]