Abstract

Background and Purpose

Low doses of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid; ASA) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. GPBAR1 is a bile acid receptor expressed in the gastrointestinal tract. Here, we have investigated whether GPBAR1 was required for mucosal protection in models of gastrointestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs.

Experimental Approch

GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice were given ASA (10–50 mg.kg−1) or naproxen. Gastric and intestinal mucosal damage was assessed by measuring lesion scores.

Key Results

Expression of GPBAR1, mRNA and protein, was detected in mouse stomach. Mice lacking GPBAR1 were more sensitive to gastric and intestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs and exhibited a markedly reduced expression of cystathionine-γ-liase (CSE), cystathionine-β-synthase (CBS) and endothelial NOS enzymes required for generation of H2S and NO, in the stomach. Treating GPBAR1+/+ mice with two GPBAR1 agonists, ciprofloxacin and betulinic acid, rescued mice from gastric injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs. The protective effect of these agents was lost in GPBAR1−/− mice. Inhibition of CSE by DL-propargylglycine completely reversed protection afforded by ciprofloxacin in wild type mice, whereas treating mice with an H2S donor restored the protective effects of ciprofloxacin in GPBAR1−/− mice. Deletion of GPBAR1 altered the morphology of the small intestine and increased sensitivity to injury caused by naproxen.

Conclusion and Implications

GPBAR1 is essential to maintain gastric and intestinal mucosal integrity. GPBAR1 agonists protect against gastrointestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs by a COX-independent mechanism.

Keywords: acetylsalicylic acid, bile acids, cystathionine-γ-liase, GPBAR1, hydrogen sulfide, NO, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Introduction

Bile acids play an important role in regulating bile acid homeostasis, nutrient absorption and lipid and glucose metabolism. They are also involved in liver and intestinal homeostasis (Fiorucci et al., 2010). This homeostatic function is mediated by the activation of a family of receptors expressed in enterohepatic tissues (Fiorucci et al., 2010). Because of their steroidal nature, bile acids signalling has been linked to activation of a specific subfamily of nuclear receptors that includes the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), the vitamin D receptor (VDR), the pregnane X receptor (PXR) and the constitutive androstane receptors (CAR) (Fiorucci et al., 2010; receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al., 2011). In addition, bile acids exert a variety of non genomic effects that have been ascribed to the activation of a cell surface receptor named GPBA or membrane-type bile acid receptor (M-BAR), a member of the rhodopsin-like superfamily of GPCR, also christened as TGR5 or bile acid-activated GPCR (GPBAR1) (Maruyama et al., 2002; Kawamata et al., 2003). Expression of GPBAR1 is restricted to gastrointestinal tissues including gallbladder, small and large intestine and stomach (Maruyama et al., 2002; Kawamata et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2006). In the stomach, expression of GPBAR1 is mainly found in enteric ganglia of the myenteric and submucosal plexus (Poole et al., 2010).

In target cells, GPBAR1 activation by secondary bile acids, lithocholic acid (LCA), deoxycholic acid (DCA) and their taurine-conjugates, tauro-LCA (TLCA) and tauro-DCA (TDCA), increases the intracellular concentrations of cAMP and causes internalization of the receptors (Maruyama et al., 2002; Kawamata et al., 2003; Katsuma et al., 2005; Fiorucci et al., 2010; Hong et al., 2010; Parker et al., 2012). In intestinal endocrine L-cells, GPBAR1 activation stimulates the secretion of glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1, an hormone that regulates insulin and glucagon secretion along with gastrointestinal motility and appetite (Kawamata et al., 2003; Katsuma et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2012). In the liver, expression of GPBAR1 has been detected in sinusoidal endothelial cells, and its activation regulates the expression of endothelial NOS (eNOS) via cAMP-responsive elements (Keitel et al., 2007). GPBAR1 is essential to maintain mucosal integrity and its genetic ablation worsens inflammation in rodent models of colitis (Cipriani et al., 2011). Of relevance, GPBAR1 is expressed in macrophages, and its activation counter-regulates secretion of inflammatory mediators by a cAMP-dependent pathway (Maruyama et al., 2002; Kawamata et al., 2003; Cipriani et al., 2011).

To date, a limited number of GPBAR1 ligands have been characterized. In addition to natural, LCA and DCA (Maruyama et al., 2002; Kawamata et al., 2003) and cholic acid (CA)-derived semisynthetic bile acids (Pellicciari et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011), only few natural GPBAR1 agonists have been discovered including triterpenoids such as betulinic acids (Genet et al., 2010; Alexander et al., 2011) and oleanolic acid (Sato et al., 2007). In the search of ligands for GPBAR1, we have recently reported that ciprofloxacin, a well-known antibiotic, is a GPBAR1 agonist that triggers cAMP accumulation in L-cells and spleen-derived macrophages in a GPBAR1-dependent manner (Cipriani et al., 2011).

Gastrointestinal bleeding caused by aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid; ASA) and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are well-recognized complications related to the use of these agents occurring at a rate of ≍3% (Wolfe et al., 1999; Fiorucci et al., 2007b; Fiorucci and Santucci, 2011). Although inhibition of gastric acid secretion by proton pump inhibitors is effective in reducing the incidence of gastric bleeding, this treatment is much less effective in protecting against intestinal injury (Abraham, 2011). ASA and non-selective NSAIDs inhibit COX-1 and -2 (Catella-Lawson et al., 2001; Fiorucci et al., 2007b). While non-selective NSAIDs are thought to injury the gastrointestinal tract through a COX-1-related mechanism, selective COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs) spare the gastrointestinal tract, but their use is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular ischemic events (Fitzgerald, 2004).

Exposure to NSAIDs not only inhibits COXs but also reduces the expression and activity of cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), a key enzyme in the generation of H2S (Fiorucci et al., 2005). As with NO, H2S protects the gastric mucosa in a prostaglandin-independent manner (Wallace, 2007; 2008; Fiorucci and Santucci, 2011). Natural and synthetic FXR ligands regulate expression of CSE by activating an FXR-responsive element in the CSE promoter (Renga, 2011).

In the present study, we demonstrated that GPBAR1 agonists protect the gastrointestinal tract against injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs. These data suggest that exploitation of GPBAR1-regulated pathways might represent a novel mechanism for protecting gastric and intestinal mucosa from detrimental effects of ASA and NSAIDs.

Methods

Animals

All animal care and experimental protocols were approved by the University of Perugia Animal Care Committee. The ID for this project is #98/2010-B. The authorization was released to Prof Stefano Fiorucci, as a principal investigator, on May 19, 2010. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (McGrath et al., 2010). The total number of animal used in these experiments was 208. C57BL6 mice were from Harlan Nossan (Udine, Italy); and GPBAR1 null mice (GPBAR1-B6 = GPBAR1−/− mice, generated directly on a C57BL/6NCrl background), and congenic littermates with the same background were kindly donated by Dr Galya Vassileva (Schering-Plough Research Institute, Kenilworth) (Vassileva et al., 2006). Mice were housed under controlled temperatures (22°C) and photoperiods (12:12 h light/dark cycle), allowed unrestricted access to standard mouse chow and tap water and allowed to acclimate to these conditions for at least 5 days before inclusion in an experiment.

Acute gastric damage

Mice were deprived of food for 16 h before oral administration of ASA, 10, 30, 50 mg kg−1. Ciprofloxacin (30 mg kg−1 i.p.), betulinic acid (10 mg kg−1 i.p.) or DL-propargylglycine (10 mg kg−1 i.p.) were administered for 5 days before administering ASA (50 mg kg−1,: orally, by gavage). Celecoxib (30 mg kg−1 orally) and l-NAME (30 mg kg−1 i.p.) were administered 1 h before ASA (50 mg kg−1). Na2S (100 μmol kg−1 i.p.) was administered 30 min before ASA (50 mg kg−1). Three hours after ASA administration, animals were killed by an overdose of pentothal (50 mg kg−1). Gastric mucosal damage was evaluated as described previously (Fiorucci et al., 2005). Samples from mouse stomachs were removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA extraction and for measurement of myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity, or fixed in formalin for histology and immunohistochemistry analysis. Tissues sections (7 μm thick) were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Generation of PGE2 by gastric mucosa was measured according to previously published methods (Fiorucci et al., 2005), using a specific elisa kit (Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI). MPO activity was measured by a spectrophotometric assay using tri-methylbenzidine (TMB) as a substrate and activity expressed as mU per mg protein (Fiorucci et al., 2005).

Nitrate/Nitrite

The concentration of gastric nitrate/nitrite was evaluated with the colorimetric Assay Kit from Cayman Chemical.

Intestinal damage

Naproxen (100 mg kg−1 orally) was administered for 5 days. On the fifth day, animals were anaesthetized with 50 mg kg−1 pentothal and killed; the small intestine was excised; and the extent of intestinal damage measured, under a microscope, by assessing the lengths of erosive and ulcerative lesions (in mm) and then summing these to obtain an individual damage score (Reuter et al., 1997). These measurements were made without knowledge of the treatments the mice had received. Small intestines from each mouse were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for measurement of MPO activity. Small intestine samples removed from GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice were fixed in formalin for histology and immunohistochemistry. Tissues sections (7 μm thick) were stained with H&E and Alcian Blue.

qRT-PCR

Quantization of the expression of selected genes was performed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). RNA (1 μg μL−1) were incubated with DNase I and reverse-transcribed with Superscript II (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) according to manufacturer specifications. For real-time PCR, 50 ng of template was used in a 25 μL reaction containing a 0.2 μM concentration of each primer and 12.5 μL of 2 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). All reactions were performed in triplicate using the following cycling conditions: 2 min at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 55 or 60°C for 30 s using an iCycler iQ instrument (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Milan, Italy). The mean value of the triplicates for each sample was calculated and expressed as cycle threshold (CT). The amount of gene expression was then calculated as the difference (ΔCT) between the CT value of the sample for the target gene and the mean CT value of that sample for the endogenous control (GAPDH). Relative expression was calculated as the difference (ΔΔCT) between the ΔCT values of the test and control samples for each target gene. The relative level of expression was measured as 2−ΔΔCT. All PCR primers were designed using the software PRIMER3-OUTPUT using published sequence data obtained from the NCBI database.

Primers used for quantitative RT-PCR were as follows:

mCSE: (s) tgctgccaccattacgatta and (as) gatgccaccctcctgaagta

mTNF-α: (s) acggcatggatctcaaagac and (as) gtgggtgaggagcacgtagt

mCOX1: (s) tgccctctgtacccaaagac and (as) tgtgcaaagaaggcaaacag

mCOX2: (s) agaaggaaatggctgcagaa and (as) gctcggcttccagtattgag

meNOS: (s) agaagagtccagcgaacagc and (as) tgggtgctgaactgacagag

miNOS: (s) acgagacggataggcagaga and (as) cacatgcaaggaagggaact

mGPBAR1: (s) ggcctggaactctgttatcg and (as) gtccctcttggctcttcctc

mCBS: (s) agaagtgccctggctgtaaa and (as) caggactgtcgggatgaagt

mGAPDH: (s) ctgagtatgtcgtggagtctac and (as) gttggtggtgcaggatgcattg

mMUC1s: (s) agtccacagtagtgcctccatc and (as) gtgcagagctggtagttgtgac

mMUC6s: (s) agaggaatgcccatgtgactat and (as) aaagcgttgtccatcaaaagtt

hGAPDH: (s) gaaggtgaaggtcggagt and (as) catgggtggaatcatattggaa

hCBS: (s) tcgtgatgccagagaagatg and (as) ttggggatttcgttcttcag

hCSE: (s) cactgtccaccacgttcaag and (as) gtggctgctaaacctgaagc

hGPBAR1: (s) actgttgtccctcctctcccta and (as) gacactgctttggctgcttg

heNOS: (s) agtgaaggcgacaatcctgtat and (as) agggacaccacgtcatactcat

Immunohistochemistry

Immediately after killing, mouse stomachs were removed and fixed in 10% buffered formalin phosphate, embedded in paraffin and sections (7 μm thickness) processed for immunohistochemistry. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized and washed in PBS, soaked in 3% H2O2 for 8 min and incubated with 5% BSA in PBS with Triton X-100 (0.1%) for 30 min. Sections were then incubated with 10 μg mL−1 of anti-GPBAR1 primary antibody (NBP1-39749, Novus Biologicals, Cambridge, UK) in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA, at room temperature for 2 h. The sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG 1:200 (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) and then processed by the avidin–biotin–peroxidase method with Vectastain ABC kit (Vector). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen. For immunohistochemistry, from small intestines of old mice, sections were deparaffinized and, after antigen retrieval, washed in PBS, soaked in 3% H2O2 for 8 min, and incubated with 5% BSA in PBS with Triton X-100 (0.1%) for 30 min. Sections were then incubated with 8 μg mL−1 rabbit anti-zonulin-1 (Invitrogen), in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA, at room temperature for 2 h. The sections were incubated with secondary biotinylated IgG 1:200 (Vector) and processed by the avidin–biotin–peroxidase method with Vectastain ABC kit (Vector). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen.

HUVEC

HUVEC, from Gibco, Italy, were maintained in supplemented Medium 200 at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air according to the instructions of the supplier. HUVEC cells at the fifth passage were starved overnight and treated with ciprofloxacin, 30 μM, or TLCA, 10 μM. Cells were then lysed in Trizol, and mRNA was extracted. HUVEC grown on chamber slides (Nunc, Inc., Naperville, IL, USA) were fixed with cooled 95% ethanol, 5% glacial acetic acid for 10 min, washed with PBS and processed for immunocytochemistry. Briefly, cells were treated with H2O2 0,75% for 8 min, washed and incubated with (1:200) anti-GPBAR1 primary antibody (NBP1-39749, Novus Biologicals) in PBS with 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% BSA, at room temperature for 1 h. Cells were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG 1:200 (Vector) and processed by the avidin–biotin–peroxidase method with Vectastain ABC kit (Vector). Diaminobenzidine was used as chromogen.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism version 3.0 was used for graphics and statistical analyses (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. For comparison of more than two groups, a one-way anova followed by Tukey's test, was used.

Materials

ASA, betulinic acid, celecoxib, ciproflaxin, Na2S, l-NAME, naproxen, dl-propargylglycine and TLCA were from Sigma Chemical Co. (Milan, Italy).

Results

Detection of GPBAR1 expression in the gastric mucosa and its functional characterization

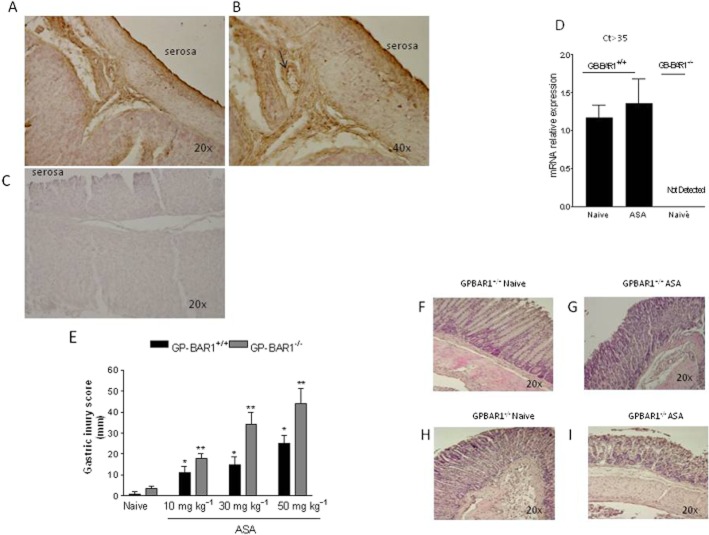

Immunoreactive GPBAR1 protein was detected in the gastric submucosa with intense staining in endothelial cells of gastric microvessels (Figure 1A, B, arrows). Expression of GPBAR1 gene in the gastric mucosa was confirmed by RT-PCR analysis, and specificity of the assay was confirmed by the absence of GPBAR1 mRNA in GPBAR1−/− mice (Figure 1D; n = 3–4 per group; P < 0.05). We then investigated whether this gene was essential in maintaining gastric homeostasis in a model of mucosal injury caused by oral administration of ASA, by challenging GPBAR1−/− mice with increasing doses of ASA. As illustrated in Figure 1E, the mucosal injury caused by ASA was markedly exacerbated in GPBAR1−/− at any dose of ASA tested (n = 4–8 per group; P < 0.05) and exposure of these mice to 10 mg kg−1 ASA resulted in a mucosal damage score that was comparable with that caused by 50 mg kg−1 in wild-type mice.. Also, GPBAR1−/− mice spontaneously developed gastric erosions in response to overnight fasting. An example of the gastric injury caused by ASA in wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice is shown in Figure 1F–I.

Figure 1.

GPBAR-1 deficiency exacerbates gastric injury caused by ASA. (A–C) Immunohistochemical analysis of GPBAR1 expression in the mouse stomach. Magnification 20× and 40×. (A and B) GPBAR1 protein is mainly expressed in submucosal vessels. (C) Negative control (magnification 20×). The secondary antibody was omitted. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of GPBAR1 mRNA expression in the stomach of GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice (ct > 35, denotes the cycle threshold) (n = 3–4). (E) Gastric mucosal injury scores in response to acute administration of 10, 30 and 50 mg kg−1 ASA to GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice (n = 4–8). (F–I). Representative examples of H&E staining of gastric mucosa of GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice exposed to ASA (50 mg kg−1). (*P < 0.05 vs. naïve GPBAR+/+; **P < 0.05 vs. naïve GPBAR1−/−).

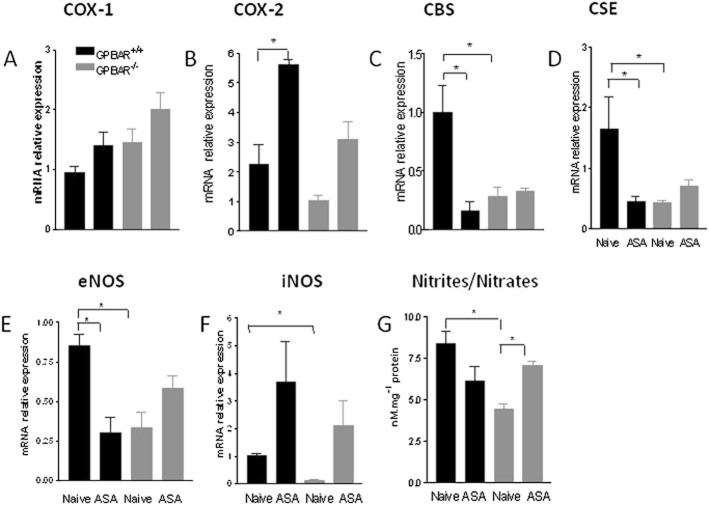

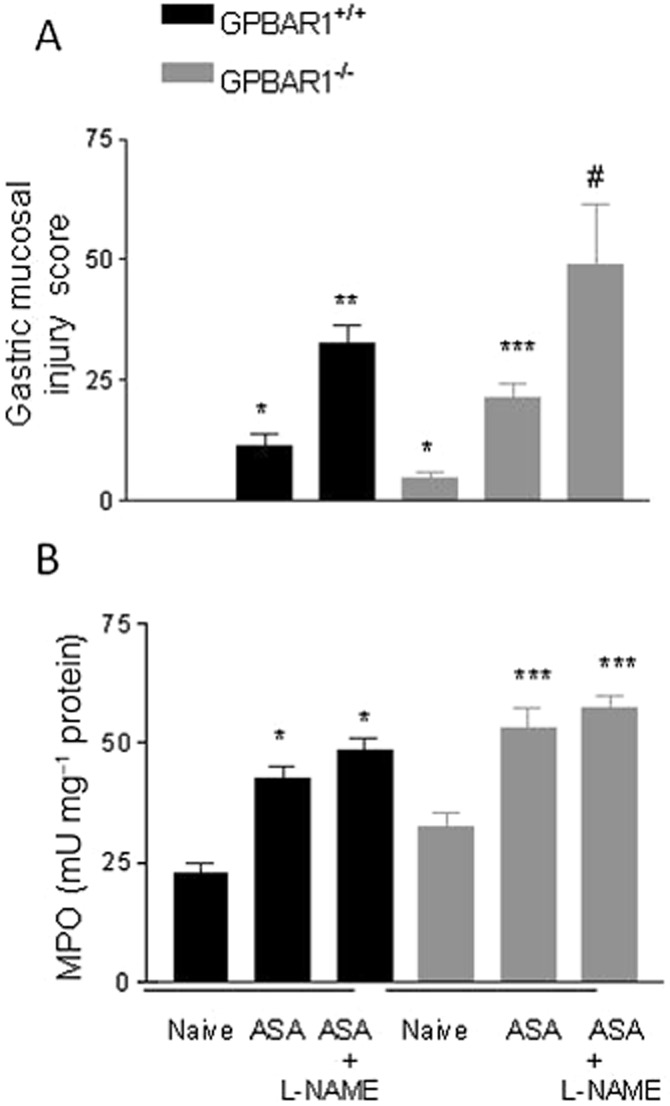

To gain insights on the mechanisms that mediate the enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− mice to gastric injury caused by ASA, we have then assessed the expression of mediators that are known to be mechanistically linked to development of gastric injury in this model. Levels of mRNA for COX-1 in gastric tissue were similar in the two mouse strains and did not change in response to ASA (50 mg kg−1). However, exposure to ASA did robustly induce COX-2 mRNA in GPBAR1+/+ mice but not in GPBAR1−/− mice (Figure 2B). In contrast to wild-type naïve mice, GPBAR1−/− mice had a marked reduction (to about 50% of that of wild-type mice) in gastric expression of CBS and CSE mRNA (Figure 2C, D). Treating GPBAR1+/+ mice with ASA (50 mg kg−1) reduced the gastric expression of CBS and CSE mRNA by 60–70% (Figure 2C, D). In addition, we found that in comparison with wild-type mice, GPBAR1−/− mice had reduced levels of eNOS gene expression (about 60%) and generated less nitrites and nitrates (Figure 2E–G). In addition, iNOS levels were also reduced in GPBAR1−/− mice (about 70%), but exposure to ASA resulted in comparable up-regulation of the enzyme in the stomach of both wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice (Figure 2F). Because these data suggested that reduced levels of eNOS might account for the enhanced susceptibility to gastric injury in GPBAR1−/− mice, we challenged wild type and GPBAR1−/− mice with l-NAME, a non-selective NOS inhibitor, (30 mg kg−1 i.p.). Results of these experiments, shown in Figure 3, demonstrate that wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice were equally sensitive to the NOS inhibitor and treatment with l-NAME worsened the severity of gastric injury caused by ASA to a comparable extent (n = 4–5 mice per group; P < 0.05), thereby indicating that differing levels of NO did not explain the enhanced sensitivity to ASA of GPBAR1−/− mice.

Figure 2.

ASA administration differentially affects gene expression in the gastric mucosa of GPBAR1 +/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. qRT-PCR analysis of expression of COX-1, COX-2, CBS,CSE, eNOS, iNOS in GPBAR1−/− and wild-type mice treated with ASA (50 mg kg−1). n = 3–4; *P < 0.05. (G) Nitrites/nitrates concentrations in the gastric mucosa of GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice treated with ASA (50 mg kg−1). n = 8; *P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Effect of l-NAME (30 mg.kg−1) on gastric damage induced by ASA in GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. (A) Gastric injury caused by ASA alone is exacerbated by exposure to l-NAME in GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. GPBAR1−/− mice show gastric lesions in response to fasting. n = 4–5 mice per group. (B) MPO activity in the stomach of GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice treated with ASA alone or in combination with l-NAME. n = 4–5. *P < 0.05 versus naïve GPBAR1+/+; **P < 0.05 versus GPBAR1+/+ treated with ASA; ***P < 0.05 versus naïve GPBAR1−/−; #P < 0.05 versus GPBAR1−/− treated with ASA.

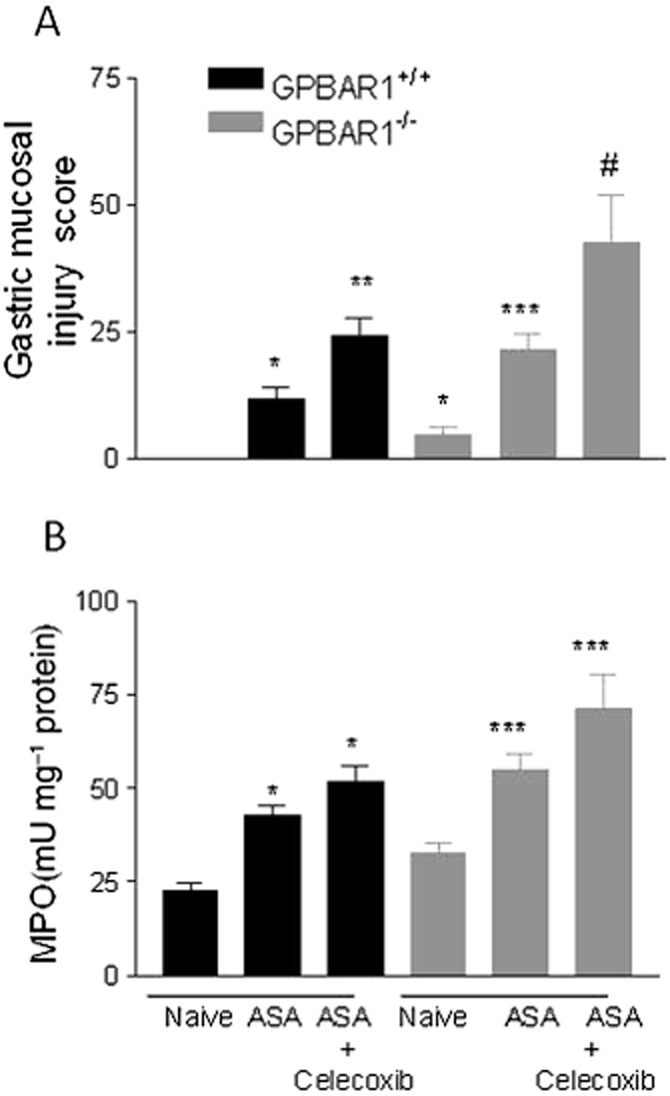

Previous studies have shown that addition of ASA to celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, worsens the severity of gastric injury caused by ASA in experimental and clinical settings. We have therefore investigated whether GPBAR1 deficiency exacerbated gastric injury caused by the combination of these two agents. Indeed, as shown in Figure 4, GPBAR1−/− mice developed more lesions than wild-type mice when challenged with a combination of ASA + celecoxib (30 mg kg−1 i.p.; Figure 4; n = 4–5 mice; P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Different response of wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice to gastric damage induced by ASA and celecoxib. (A) Gastric injury caused by ASA alone or in combination with celecoxib (30 mg kg−1) is exacerbated in GPBAR1−/− mice. (B) MPO activity measured in the stomach of mice treated with ASA alone or in combination with celecoxib. n = 4–5. *P < 0.05 versus naïve GPBAR1+/+; **P < 0.05 versus GPBAR1+/+ treated with ASA; ***P < 0.05 versus naïve GPBAR1−/−; #P < 0.05 versus GPBAR1−/− treated with ASA.

Activation of GPBAR1 protects against intestinal injury caused by NSAIDs

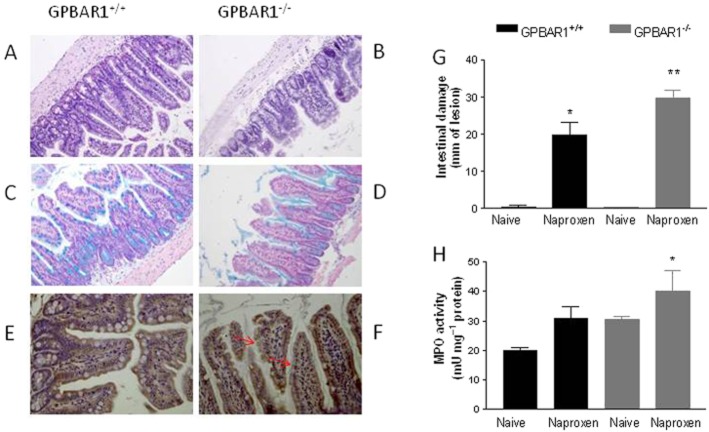

We then investigated whether GPBAR1 deletion exacerbated intestinal damage caused by naproxen (100 mg kg−1 day−1 for 5 days). As illustrated in Figure 5, deletion of GPBAR1 altered the morphology of distal ileum resulting in short villi (Figure 5A, B, H&E staining) and reduced secretion of mucins (Figure 5C, D, Alcian Blue staining) and abnormal distribution of zonulin-1 (immunostaining; Figure 5E, F). These changes become more evident with age. Intestinal injury caused by naproxen in three-month-old mice was exacerbated in GPBAR1−/− mice (Figure 5G; n = 3–5; P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

GPBAR1 is required to maintain the integrity of the small intestine. (A, B) H&E staining of small intestine from 9-month-old GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. (C, D) Alcian blue staining of small intestine from 9-month-old GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. (E, F) Immunohistochemical detection of zonulin-1 in small intestine from 9-month-old GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. Zonulin- 1 is shown by a brown staining, and tissue sections are counterstained with haematoxylin, violet staining The staining of the protein increases in GPBAR1−/− animals, but its cellular localization appears to be discontinuous. Original magnification, 20×. (G) Intestinal damage score and (H) MPO activity in small intestines from GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/−, 3-month-old mice treated with naproxen (100 mg kg−1). n = 4–5. *P < 0.05 versus naïve GPBAR1+/+ mice, **P < 0.05 versus GPBAR1+/+ mice treated with naproxen.

Activation of GPBAR1 protects against gastrointestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs

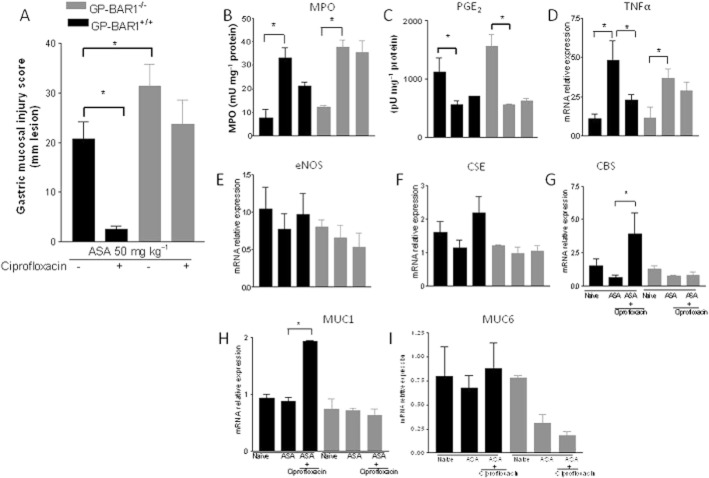

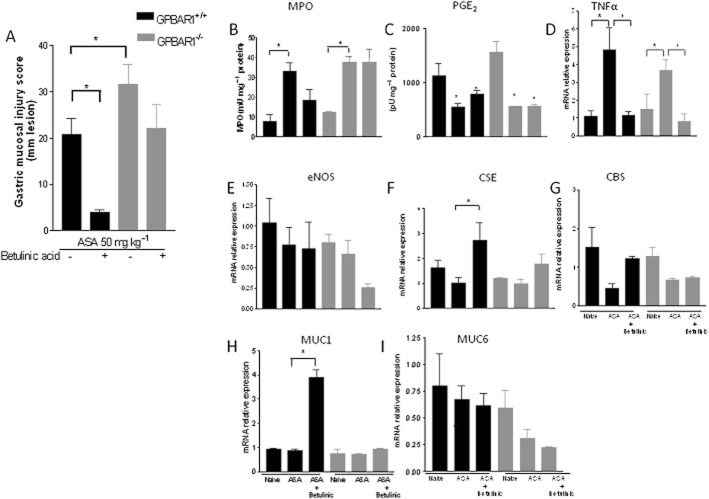

Because these data highlight a functional role of GPBAR1 in the gastric and intestinal mucosa that is protective in nature, we then investigated whether activation of GPBAR1 by natural and synthetic ligands would protect against gastric injury caused by ASA. Data shown in Figures 6 and 7 demonstrate that activation of GPBAR1 with ciprofloxacin or betulinic acid, two GPBAR1 agonists, administered orally at 30 and 10 mg kg−1, respectively, for 5 days, protected against development of acute gastric damage caused by 50 mg kg−1 ASA (n = 4–7; P < 0.05) in wild-type mice. Protection exerted by GPBAR1 agonists resulted in a reduced mucosal injury score (Figures 6A and 7A, P < 0.05 vs. ASA alone), attenuated influx of neutrophils (MPO level) (Figures 6B and 7B, P < 0.05) and reduced expression of TNF-α mRNA (Figures 6D and 7D; P < 0.05). Importantly these protective effects were lost when ciprofloxacin and betulinic acid were administered to GPBAR1−/− mice (Figures 6 and 7), though betulinic acid was still able to reduce TNF-α mRNA in this strain (Figure 7D). Protection afforded by GPBAR1 agonists was prostanoid independent since both agents had no effect on PGE2 inhibition caused by ASA (Figures 6C and 7C; P < 0.05. As shown in Figures 6E and 7E, exposure to GPBAR1 agonists failed to modulate the expression of eNOS, although it caused a robust induction of CSE and CBS mRNA in wild-type mice (Figures 6F, G and 7F, G; P < 0.05). Again, the effects exerted by ciprofloxacin and betulinic acid were GPBAR1-dependent and lost in GPBAR1−/− mice. In addition, treating mice with GPBAR1 agonists resulted in the induction of MUC1 mRNA in wild-type, but not in GPBAR1−/− mice (Figures 6H and 7H).

Figure 6.

GPBAR1 activation by ciprofloxacin protects against gastric damage induced by ASA in GPBAR1+/+ but not in GPBAR1−/− mice. (A) Mucosal damage score. (B) MPO activity. (C) PGE2 level. (D–I) qRT-PCR of TNF-α, eNOS, CSE, CBS, MUC1, MUC6 expression in GPBAR+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice treated with ASA alone (50 mg kg−1) or in combination with ciprofloxacin (30 mg kg−1). (n = 4–7; *P < 0.05).

Figure 7.

GPBAR1 activation by betulinic acid protects against gastric damage induced by ASA in GPBAR1+/+ but not in GPBAR1−/− mice. (A) Mucosal damage score. (B) MPO activity. (C) PGE2 level. (D–I) qRT-PCR of TNF-α, eNOS, CSE, CBS, MUC1, MUC6 expression in GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice treated with ASA alone (50 mg kg−1) or in combination with betulinic acid (10 mg kg−1). (n = 3–7; *P < 0.05).

Beneficial effects of GPBAR1 ligands are mediated by CSE

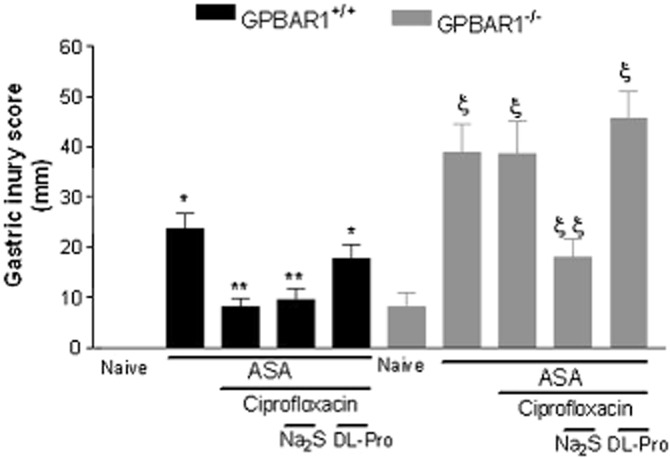

To gain further insights on the protective mechanisms exerted by GPBAR1 agonists, we gave ciprofloxacin to wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice and then treated them with with Na2S, an H2S donor, or dl-propargylglycine (10 mg kg−1 i.p.), a CSE inhibitor, before exposure to ASA, 50 mg kg−1. Data shown in Figure 8 demonstrate that while ciprofloxacin effectively protected wild-type mice against gastric injury caused by ASA, and its effect was unchanged by administering Na2S (Figure 8; n = 4–5; P < 0.05), inhibition of CSE activity with dl-propargylglycine (10 mg kg−1) completely prevented the protection exerted by ciprofloxacin (Figure 8; n = 4–5; P < 0.05). The opposite was observed in GPBAR1−/− mice. Indeed, while ciprofloxacin failed to protect against injury caused by ASA and treatment with dl-propargylglycine (10 mg kg−1) failed to exacerbate the severity of gastric injury caused by ASA, treating GPBAR1−/− mice with Na2S effectively rescued the animals from injury caused by ASA (Figure 8; P < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Na2S (100 μmol kg−1 i.p.) and dl-propargylglycine (10 mg kg−1 i.p.) modulate the activity of ciprofloxacin in GPBAR1+/+ and GPBAR1−/− mice. Ciprofloxacin protects against gastric injury caused by ASA in GPBAR1+/+ mice and dl-propargylglycine (DL-Pro) reverses protection exerted by ciprofloxacin. Failure of ciprofloxacin to protect against injury caused by ASA in GPBAR1−/− mice is reversed by co-treatment with Na2S. GPBAR1−/− mice show gastric lesions in response to fasting. n = 4–5. P < 0.05 versus naïve; ** versus ASA in GPBAR+/+ mice; § versus naïve, § § versus ASA in GPBAR1−/− mice.

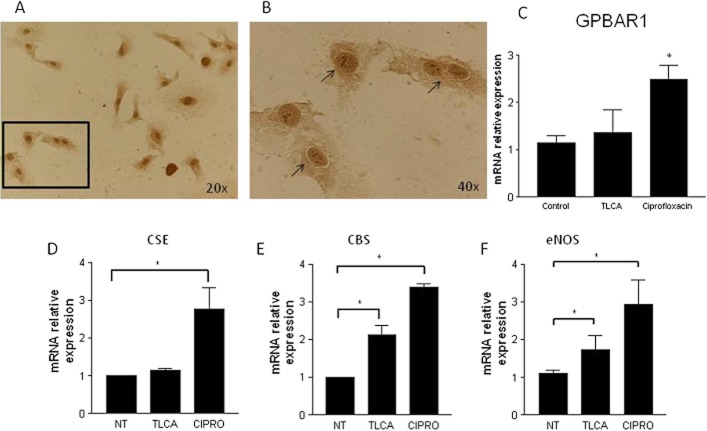

Detection of GPBAR1 in HUVEC cells and CSE modulation

Because these data highlighted a functional role for H2S generating enzymes in protection afforded by GPBAR1 agonists and immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that GPBAR1 was mainly located in endothelial cells of gastric mucosa, we investigated whether GPBAR1 was expressed in human endothelial cells and whether exposure of these cells to GPBAR1 ligands regulated the expression of genes involved in H2S and NO generation. For this purpose, HUVEC were used. By immunocytochemistry (Figure 9A, B), we detected GPBAR1 mRNA in these cells with a typical cell surface staining, and the presence of GPBAR1 gene was further confirmed by RT-PCR (Figure 9C). Furthermore, exposure of HUVEC to TLCA (10 μM) and ciprofloxacin (30 μM) significantly increased the expression of CSE (ciprofloxacin only), CBS and eNOS mRNA (Figure 9D–F).

Figure 9.

Human endothelial cells express GPBAR1. (A, B) Immunohistochemical analysis of GPBAR1 in HUVEC cells. Arrows indicate cell membrane staining of GPBAR1 in HUVEC. qRT-PCR analysis of (C) GPBAR1, (D) CSE, (E) CBS and (F) eNOS mRNA in HUVEC left untreated (NT) or treated with TLCA (10 μM) or ciprofloxacin (CIPRO; 30 μM). (*P < 0.05 vs. control).

Discussion

Gastrointestinal side effects including ulcerations, bleeding and perforations are well-recognized complications of the clinical use of ASA and NSAIDs. The risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients taking low doses of ASA (<100 mg day−1) or medium doses of any NSAID increases approximately fourfold in comparison with untreated populations (Wolfe et al., 1999). The pathogenesis of gastrointestinal injuries caused by ASA and NSAIDs is ascribed to the suppression of COX-1; however, additional mechanisms are involved (Fiorucci et al., 2003).

In the present study, we have provided evidence that the bile acid receptor GPBAR1 is required for maintenance of gastrointestinal mucosal integrity, and that this protective effect is prostaglandin independent. This contention emerges from the results of studies carried out in GPBAR1−/− mice. Despite these mice showing normal gastric morphology, they developed severe and extensive injury when challenged with ASA. This enhanced susceptibility was COX-independent because expression of COX-1 and COX-2 mRNAs in the gastric mucosa was regulated similarly in wild-type and GPBAR1−/− mice, and the magnitude of the suppressive effect exerted by ASA on the formation of PGE2 was comparable in the two mouse strains. The enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− mice to COX-inhibiting agents extended beyond the stomach, because GPBAR1−/− mice also developed severe intestinal injury in response to naproxen, in a validated model of intestinal damage.

In the search for a mechanism that could support the enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− to gastrointestinal damage caused by ASA and NSAIDs, we have investigated the role of NO and H2S, two gaseous mediators that exert homeostatic function in the gastric and intestinal mucosa (Fiorucci, 2001; Fiorucci et al., 2007a). Previous studies have shown that bile acids increase the expression of eNOS by a GPBAR1 and cAMP-dependent mechanism in isolated sinusoid endothelial cells, a liver-specific endothelial cell subtype (Keitel et al., 2007). Here, we report that GPBAR1−/− mice had reduced levels of eNOS mRNA in the gastric mucosa, highlighting a functional role for GPBAR1 in regulating eNOS gene transcription. However, these reduced levels of eNOS did not represent the sole cause for the enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− mice to injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs, as eNOS deficiency was compensated for by a robust induction of iNOS (about 5-fold in comparison with naïve GPBAR1+/+ mice).

In addition to the NOS isoforms, CSE, an enzyme involved in biosynthesis of H2S from homocysteine and l-cysteine, is selectively targeted by NSAIDs in the gastric mucosa (Fiorucci et al., 2005; Wallace, 2008). In a previous study, we have shown that exposure of wild-type mice to NSAIDs attenuates CSE expression in the gastric mucosa and impairs the generation of H2S (Fiorucci et al., 2011). Of relevance, H2S reversed the gastric injury caused by NSAIDs in a COX- and NOS-independent manner (Wallace, 2008). Here we report that that GPBAR1−/− mice have an impaired expression of CSE mRNA in the stomach (≍50% of wild-type mice) and develop gastric injury in response to fasting. To our knowledge, this is the first model in which the simple food deprivation causes erosive lesions, strongly supporting a homeostatic role of GPBAR1 in gastric mucosa. In addition, GPBAR1−/− mice were more sensitive to gastric and intestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs. Because these animals were rescued by exposure to an H2S donor and the severity of gastric injury was not further exacerbated by exposure to a CSE inhibitor, these data suggest that reduced expression of CSE and H2S generation provides a robust mechanistic explanation of the enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− mice to the gastrointestinal injuries caused by ASA and NSAIDs.

We speculated that GPBAR1 activation could protect against gastric injury induced by ASA through the regulation of CSE and CBS expression in endothelial cells in the gastric microcirculation. Thus, not only expression of GPBAR1 was detected in endothelial cells of gastric mucosa and in an endothelial cell line, but treatment of HUVEC with TLCA and ciprofloxacin up-regulated the expression of CSE (ciprofloxacin), CBS and eNOS mRNA. Present data are consistent with the reported ability of TLCA to increase the expression/activity of eNOS via a cAMP-responsive element in liver sinusoidal cells (Keitel et al., 2007).

We have previous reported that ciprofloxacin, a well-known antibiotic, exerted non-antibiotic activities that were mediated by its interaction with GPBAR1 (Cipriani et al., 2011). In mouse monocytes, ciprofloxacin increased cAMP concentrations and attenuated TNF-α release in a GPBAR1-dependent manner. Furthermore, ciprofloxacin prevents signs and symptoms of inflammation in mouse models of colitis by a GPBAR1-dependent mechanism. Betulinic acid is a naturally ocurring compound and a potent GPBAR1 agonist (Genet et al., 2010; Alexander et al., 2011). Using these two agents, we have shown that GPBAR1 activation rescued wild type mice from gastric injury caused by ASA and that this protective effect relied on the regulation of CSE/CBS expression in the gastric mucosa. Support for this concept came from the finding that co-administration of dl-propargylglycine with ciprofloxacin reversed the protective effects exerted by this antibiotic. Altogether, these data support the notion that a dysregulated expression of CSE in the gastrointestinal mucosa makes an important contribution to the enhanced susceptibility of GPBAR1−/− mice to damage caused by ASA and NSAIDs.

Gastric expression of membrane (MUC1) and secreted (MUC5AC, MUC6) mucins is altered in models of reactive gastropathy (Mino-Kenudson et al., 2007). Importantly, MUC-1 expression is reduced in stomach of patients exposed to NSAIDs (Guang et al., 2010; Costa et al., 2011; Saeki et al., 2011). The finding that GPBAR1−/− mice react to exposure to ASA by a marked reduction of MUC1 expression and that ciprofloxacin increases the expression of this gene in wild-type mice challenged with ASA highlight a possible regulatory role for GPBAR1 on MUC1 expression.

Bile acids activate several nuclear receptors and G-protein-coupled cell surface receptors exerting a wide range of genomic and non-genomic effects (Fiorucci et al., 2011). We have recently reported that FXR, the main bile acid sensor in enterohepatic tissues, is also essential to maintain gastrointestinal homeostasis; and that its ablation enhances sensitivity to gastric and intestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs as well as to inflammation in rodent models of colitis (Vavassori et al., 2009; Fiorucci et al., 2011). Gastric protection exerted by FXR ligation by the potent synthetic agonist GW4064 was partially mediated by induction of CSE in the gastric mucosa. The effect exerted by FXR on CSE expression appears to be mediated by a direct binding of this nuclear receptor to an FXR-responsive element in the CSE promoter and is therefore different from the non-genomic, cAMP-mediated effect exerted by GPBAR1 (Keitel et al., 2007). The fact that FXR and GPBAR1 converge on regulation of eNOS, CSE and CBS by genomic and non-genomic effects might explain the enhanced susceptibility of FXR- and GPBAR1-deficient mice to ASA and NSAIDs (Fiorucci et al., 2010).

Previous observations have shown that bile acids function as barrier breakers in the gastric mucosa and enhance gastric and intestinal injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs (Zhou et al., 2010). Because bile acids, especially secondary bile acids, are directly cytotoxic for a variety of cells and tissues, their intracellular concentrations are tightly regulated by the intervention of a family of nuclear receptors (FXR, CAR and PXR) that orchestrate their import, conjugation and excretion (Fiorucci et al., 2010). FXR−/− mice develop a number of intestinal and liver pathologies due to the accumulation of toxic concentrations of bile acids. GPBAR1-deficient mice had a reduced bile acid pool (Maruyama et al., 2006), but because the liver expression of the gene encoding CYP8B1, an enzyme that regulates the ratio between cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) is increased, they have higher levels of CA. Thus, the fact that mice lacking FXR and GPBAR1 are more prone to develop gastrointestinal injury in response to ASA is fully consistent with the observation that locally applied bile acids are barrier breaking agents (Zhou et al., 2010). Furthermore, because GPBAR1 activation by ciprofloxacin and betulinic acid rescues cells from injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs, it is a strong demonstration that toxic effects exerted by bile acids in these models are receptor-independent.

The present findings might have important translational outcomes. Indeed, the GPBAR1–CSE–H2S pathways could be exploited therapeutically by designing novels COX inhibitor hybrids that release H2S or activate the GPBAR1–CSE pathway to spare the intestinal mucosa (Wallace et al., 2010; Fiorucci and Santucci, 2011). Thus, while a number of approaches are presently available to effectively protect the gastric mucosa against damage caused by ASA and NSAIDs, the same is not true for the intestinal injury caused by these agents (Laine et al., 2008). Intestinal complications caused by COX-1 inhibitors are not efficiently prevented by co-treatment with proton pump inhibitors (Goldstein et al., 2007) and, while selective COX-2 inhibitors spare the intestinal mucosa (Goldstein et al., 2007), their use is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular ischemic events (Fitzgerald, 2004). In this context, development of GPBAR1 agonists to protect the intestinal mucosa might have relevance in the management of patients taking ASA or NSAIDs who are at a high risk of developing gastrointestinal and cardiovascular complications for whom the selective COX-2 inhibitors could not be recommended.

In summary, we have shown that GPBAR1, a bile acid receptor, plays an essential role in maintaining gastric and intestinal barrier integrity. Exploitation of GPBAR1-regulated pathways might represent a novel mechanism for protecting gastric and intestinal mucosa from injury caused by ASA and NSAIDs.

Glossary

- ASA

acetyl salicylic acid

- CA

cholic acid

- CAR

constitutive androstane receptor

- CDCA

chenodeoxycholic acid

- CBS

cystathionine-β-synthase

- CSE

cystathionine-γ-lyase

- FXR

farnesoid X-receptor

- GPBAR1

G protein bile acid activated receptor 1

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- ICAM-1

intracellular adhesion molecule-1

- LCA

lithocholic acid

- MPO

myeloperoxidase

- MUC1 and 6

mucin 1 and 6

- NSAIDs

non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PXR

pregnane X-receptor

- TLCA

tauro-lithocholic acid

- VDR

vitamin D receptor

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to be disclosed.

References

- Abraham NS. Prescribing proton pump inhibitor and clopidogrel together: current state of recommendations. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:558–564. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834a382e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptor and channel 5th edition: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:5–113. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catella-Lawson F, Reilly MP, Kapoor SC, Cucchiara AJ, DeMarco S, Tournier B, et al. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors and the antiplatelet effects of aspirin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1809–1817. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani S, Mencarelli A, Chini MG, Distrutti E, Renga B, Bifulco G, et al. The bile acid receptor GPBAR-1 (TGR5) modulates integrity of intestinal barrier and immune response to experimental colitis. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25637. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa NR, Paulo P, Caffrey T, Hollingsworth MA, Santos-Silva F. Impact of MUC1 mucin downregulation in the phenotypic characteristics of MKN45 gastric carcinoma cell line. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S. NO-releasing NSAIDs are caspase inhibitors. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:232–235. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01904-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Santucci L. Hydrogen sulfide-based therapies: focus on H2S releasing NSAIDs. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:133–140. doi: 10.2174/187152811794776213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Distrutti E, de Lima OM, Romano M, Mencarelli A, Barbanti M, et al. Relative contribution of acetylated cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2 and 5-lipooxygenase (LOX) in regulating gastric mucosal integrity and adaptation to aspirin. FASEB J. 2003;17:1171–1173. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0777fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Distrutti E, Rizzo G, Mencarelli A, Orlandi S, et al. Inhibition of hydrogen sulfide generation contributes to gastric injury caused by anti-inflammatory nonsteroidal drugs. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1210–1224. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Orlandi S, Mencarelli A, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Distrutti E, et al. Enhanced activity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of mesalamine (ATB-429) in a mouse model of colitis. JL. Br J Pharmacol. 2007a;150:996–1002. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Santucci L, Distrutti E. NSAIDs, coxibs, CINOD and H2S-releasing NSAIDs: what lies beyond the horizon. Dig Liver Dis. 2007b;39:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Cipriani S, Baldelli F, Mencarelli A. Bile acid-activated receptors in the treatment of dyslipidemia and related disorders. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorucci S, Mencarelli A, Cipriani S, Renga B, Palladino G, Santucci L, et al. Activation of the farnesoid-X receptor protects against gastrointestinal injury caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1929–1938. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald GA. Coxibs and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1709–1711. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genet C, Strehle A, Schmidt C, Boudjelal G, Lobstein A, Schoonjans K, et al. Structure-activity relationship study of betulinic acid, a novel and selective TGR5 agonist, and its synthetic derivatives: potential impact in diabetes. J Med Chem. 2010;53:178–190. doi: 10.1021/jm900872z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, Gralnek IM, Aisenberg J, Bhadra P, et al. Small bowel mucosal injury is reduced in healthy subjects treated with celecoxib compared with ibuprofen plus omeprazole, as assessed by video capsule endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1211–1222. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guang W, Ding J, Czinn SJ, Kim CK, Blanchard TG, Lillehoj EP. Muc1 cell surface mucin attenuates epithelial inflammation in response to a common mucosal pathogen. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:20547–20557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Behar J, Wands J, Resnick M, Wang LJ, DeLellis RA, et al. Role of a novel bile acid receptor TGR5 in the development of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Gut. 2010;59:170–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.188375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuma S, Hirasawa A, Tsujimoto G. Bile acids promote glucagon like peptide-1 secretion through TGR5 in a murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. Biochem Biophis Res Comm. 2005;329:386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata Y, Fujii R, Hosoya M, Harada M, Yoshida H, Miwa M, et al. A G protein-coupled receptor responsive to bile acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9435–9440. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keitel V, Reinehr R, Gatsios P, Rupprecht C, Görg B, Selbach O, et al. The G-protein coupled bile salt receptor TGR5 is expressed in liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. Hepatology. 2007;45:695–704. doi: 10.1002/hep.21458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine L, Curtis SP, Langman M, Jensen DM, Cryer B, Kaur A, et al. Lower gastrointestinal events in a double-blind trial of the cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective inhibitor etoricoxib and the traditional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug diclofenac. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1517–1525. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Miyamoto Y, Nakamura T, Tamai Y, Okada H, Sugiyama E, et al. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR) Biochem Bophys Res Commun. 2002;298:714–719. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02550-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama T, Tanaka K, Suzuki J, Miyoshi H, Harada N, Nakamura T, et al. Targeted disruption of G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Gpbar1/M-Bar) in mice. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:197–205. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reportingexperiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mino-Kenudson M, Tomita S, Lauwers GY. Mucin expression in reactive gastropathy: an immunohistochemical analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:86–90. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-86-MEIRGA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker HE, Wallis K, le Roux CW, Wong KY, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Molecular mechanisms underlying bile acid-stimulated glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:414–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicciari R, Gioiello A, Macchiarulo A, Thomas C, Rosatelli E, Natalini B, et al. Discovery of 6alpha-ethyl-23(S)-methylcholic acid (S-EMCA, INT-777) as a potent and selective agonist for the TGR5 receptor, a novel target for diabesity. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7958–7961. doi: 10.1021/jm901390p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DP, Godfrey C, Cattaruzza F, Cottrell GS, Kirkland JG, Pelayo JC, et al. Expression and function of the bile acid receptor GP-BAR1 (TGR5) in the murine enteric nervous system. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:814–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renga B. Hydrogen sulfide generation in mammals: the molecular biology of cystathionine-β- synthase (CBS) and cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:85–91. doi: 10.2174/187152811794776286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter BK, Davies NM, Wallace JL. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy in rats: role of permeability, bacteria, and enterohepatic circulation. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:109–117. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki N, Saito A, Choi IJ, Matsuo K, Ohnami S, Totsuka H, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in mucin 1, at chromosome 1q22, determines susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:892–902. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H, Genet C, Strehle A, Thomas C, Lobstein A, Wagner A, et al. Anti-hyperglycemic activity of a TGR5 agonist isolated from Olea europea. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;362:793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassileva G, Golovko A, Markowitz L, Abbondanzo SJ, Zeng M, Yang S, et al. Targeted deletion of Gpbar1 protects mice from cholesterol gallstone formation. Biochem J. 2006;398:423–430. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavassori P, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S. The bile acid receptor FXR is a modulator of intestinal innate immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:6251–6261. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL. Hydrogen sulfide-releasing anti-inflammatory drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL. Prostaglandins, NSAIDs, and gastric mucosal protection: why doesn't the stomach digest itself? Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1547–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Caliendo G, Santagada V, Cirino G. Markedly reduced toxicity of a hydrogen sulphide-releasing derivative of naproxen (ATB-346) Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:1236–1246. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YD, Chen WD, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. The G-Protein-coupled bile acid receptor, Gpbar1 (TGR5), negatively regulates hepatic inflammatory response through antagonizing nuclear factor kappa light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) in mice. Hepatology. 2011;54:1421–1432. doi: 10.1002/hep.24525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, et al. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature. 2006;439:484–489. doi: 10.1038/nature04330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1888–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906173402407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Dial EJ, Doyen R, Lichtenberger LM. Effect of indomethacin on bile acid-phospholipid interactions: implication for small intestinal injury induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G722–G731. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00387.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]