Abstract

Background and Purpose

An important objective in asthma therapy is to prevent the accelerated growth of airway smooth muscle cells which leads to hyperplasia and bronchial hyperreactivity. We investigated the effect of combination of salbutamol and PPARγ agonists on growth factor-stimulated human bronchial smooth muscle cell (BSMC) proliferation.

Experimental Approach

Synergism was quantified by the combination index-isobologram method. Assays used here included analyses of growth inhibition, cell viability, DNA fragmentation, gene transcription, cell cycle and protein expression.

Key Results

The PPARγ gene was highly expressed in BSMC and the protein was identified in cell nuclei. Single-agent salbutamol or PPARγ agonists prevented growth factor-induced human BSMC proliferation within a micromolar range of concentrations through their specific receptor subtypes. Sub-micromolar levels of combined salbutamol-PPARγ agonist inhibited growth by 50% at concentrations from ∼2 to 12-fold lower than those required for each drug alone, without induction of apoptosis or necrosis. Combination treatments also promoted cell cycle arrest at the G1/S transition phase and inhibition of ERK phosphorylation.

Conclusions and Implications

The synergistic interaction between PPARγ agonists and β2-adrenoceptor agonists on airway smooth muscle cell proliferation highlights the anti-remodelling potential of this combination in chronic lung diseases.

Keywords: airway remodelling, airway smooth muscle cell, asthma, PPARγ agonists, salbutamol, synergism

Introduction

Airway remodelling, that is, the development of structural changes in the airway wall, represents a critical step in the pathophysiology of asthma (Hirst et al., 2000; Bentley and Hershenson, 2008; Jarjour et al., 2012). It has been widely recognized that, at variance with intermittent or mild to moderate asthma, patients with severe long-standing disease are usually highly symptomatic, difficult to treat and can be extremely refractory to current treatments (Hassan et al., 2010; Parfrey et al., 2010). Noteworthy, the absence of response to corticosteroids is related to subepithelial thickness and is a potential signal for an important remodelling process (Bourdin et al., 2012). Finally, children who suffer from severe, persistent asthma, require high dose inhaled or near continuous oral glucocorticoid treatment to maintain disease control and have a high risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in adulthood (Firszt and Kraft, 2010).

Regulation of airway smooth muscle hyperplasia is considered an attractive strategy for novel therapeutic interventions aimed at preventing disease progression in asthma patients, and cell culture techniques have been extensively used to test anti-remodelling drugs (Ammit and Panettieri, 2003). A large number of mitogenic factors generated by the inflammatory process in asthma patients, including polypeptide growth factors such as PDGF and EGF, contractile agents such as thromboxane and leukotriene D4 and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α, stimulate proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells in culture, and are probable contributors to airway wall remodeling in vivo. These diverse extracellular stimuli regulate cell cycle entry and DNA synthesis by activating common signalling pathways, such as ERK, (also known as MAPK; Hirst et al., 2000).

β2-Adrenoceptor agonists and glucocorticosteroids alone or in combination, represent the foundation of pharmacotherapy for chronic lung diseases (Niewoehner, 2010). However, despite their capacity to alleviate symptoms and decrease exacerbations of disease, these drugs do not fully reverse the structural changes that occur during the progression of the pathological state. These considerations highlight the need for identification of alternative drug targets as a logical approach to select novel therapeutic interventions in asthma that would be able to prevent or arrest airway remodelling and disease progression.

PPARs are a family of nuclear hormone receptors that play a role in the pathophysiology of lung-related diseases. Activation of these receptors by natural or pharmacological ligands leads to both gene-dependent and gene-independent effects that alter the expression of a wide array of proteins (Belvisi and Mitchell, 2009). Several lines of evidence suggest that PPARγ ligands may have anti-inflammatory effects in asthma and are endowed with anti-proliferative and anti-angiogenic properties in epithelial lung cancers (Denning and Stoll, 2006). Furthermore, PPARγ agonists reversed β2-adrenoceptor tolerance induced by prolonged exposure of human bronchial smooth muscle cells (BSMCs) to salbutamol (Fogli et al., 2011), thus supporting the potential combined benefit of PPARγ agonists and drugs currently used in the treatment of asthma.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the potential interaction between PPARγ ligands and the β2-adrenoceptor agonist, salbutamol, on human BSMC proliferation stimulated by serum and growth factor-supplemented medium.

Methods

Cell cultures

Human BSMCs (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) were maintained as recommended by the manufacturer in an optimized medium containing 5% FBS, 5.5 mM glucose, 50 μg·mL−1 gentamicin, 50 ng·mL−1 amphotericin-B, 5 ng·mL−1 insulin, 2 ng·mL−1 basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and 0.5 ng·mL−1 EGF (SmGM-2 Bullet Kit, Lonza).

Real-time PCR

RNA from cells was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini kit and reverse-transcribed by the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit. The concentration and purity of total RNA were measured by 260 nm UV absorption and by 260/280 ratios, respectively, using NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Wilmington, DE, USA); all RNAs displayed a 260/280 optical density ratio >1.9. The RNA integrity was verified by electrophoresis through 1.2% agarose-formaldehyde gel.

The resulting cDNA was amplified by quantitative PCR with the Applied Biosystems 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR reactions were performed in triplicate using 5 μL of cDNA, 12.5 μL of TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, 43.75 μL of probe and 2.5 μL of forward and reverse primers in a final volume of 25 μL. Samples were amplified using the following thermal profile: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 s followed by annealing and extension at 60°C for 1 min.

Forward and reverse primers and probes for PPARγ were purchased from Applied Biosystems Made-to-order(R) products. Amplifications were normalized to GAPDH. Preliminary experiments were carried out with dilutions of cDNA obtained from Quantitative PCR Human Reference Total RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) to demonstrate that the efficiencies of amplification of the target and reference genes are approximately equal and to determine the absolute value of the slope of standard cDNA concentration versus CT, where CT is the threshold cycle.

Human melanoma (MeWo) and pancreatic cancer (MIA PaCa-2) cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively, based on a previously published work (Subbarayan et al., 2005).

PPARγ transcription factor assay

Nuclear protein extracts was obtained from serum-starved BSMC in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone 0.5 μM (Nuclear extract Kit, Cayman Chemical Company, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and then the presence of functional PPARγ protein was confirmed by a sensitive and specific ELISA method (Cayman Chemical Company). Experiments were performed in the absence or presence of a competitor double-stranded oligonucleotide to confirm the assay specificity.

Single-agent effect on BSMC growth

BSMCs were sub-cultured into 24-well plates (Corning Life Sciences, Tewksbury, MA, USA) at a density of 104 cells per well overnight and kept in serum-free medium for 24 h. This incubation was designed to deprive the cells of serum mitogens and produce growth arrest to synchronize cell proliferation upon subsequent stimulation. BSMCs were then incubated in growth medium and concentration-response curves were obtained following 48 h exposure to salbutamol (β2-adrenoceptor agonist; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at 0.01–200 μM, rosiglitazone or 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (PGJ2) (selective PPARγ agonists; Cayman Chemical Company) at 0.5–100 and 0.1–50 μM, respectively; and dexamethasone (Sigma Aldrich) at 0.1–100 μM. In a separate set of experiments, the following antagonists were added 30 min before addition of the agonist: butoxamine (β2-adrenoceptor) at 0.1–100 μM, GW9662 (PPARγ) at 0.1–50 μM (Sigma Aldrich), and RU486 (glucocorticoid receptor, Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO, USA) at 0.1–100 μM Receptor nomenclature follows Alexander et al. (2011). At the end of the experiments, cells were harvested and counted by haemocytometer and changes in cell growth were expressed as a percentage relative to day 0. The potential cytotoxic effect of compounds at the maximum concentrations tested in growth inhibition assay was then evaluated on BSMC cultured in growth factor-free medium.

Quantitation of the synergism between compounds

Cells were cultured as for single experiments and treated for 48 h with salbutamol (0.1 or 0.5 μM) plus PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone at the fixed ratio of 1:1. The combination index (CI)-isobologram method was applied to analyse data from the in vitro drug-combination study (Chou et al., 1994). Briefly, synergism or antagonism for salbutamol plus PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone was calculated on the basis of the multiple drug-effect equation, and quantified by the CI, where CI < 1, CI = 1 and CI > 1 indicate synergism, additive effect and antagonism respectively. Based on the classic isobologram for mutually exclusive effects, CI values were calculated as follows: CI = [(D)1/(Dx)1] + [(D)2/(Dx)2], where (D)1 and(D)2 are the concentrations of salbutamol and PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone in combinations that induced an x% of cell growth inhibition, while (Dx)1 and (Dx)2 are the calculated concentrations for x% inhibition by salbutamol and PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone respectively. Dx values were obtained from the following equation: (Dx) = Dm[fa/(1-fa)]1 m−1, where Dm is the median-effect dose (ED50) of the single drug, fa is the fractional inhibition, (1-fa) is the fraction unaffected and m is the coefficient signifying the shape of the dose-effect curves.

The dose-reduction index (DRI) defines the extent (fold change) of concentration reductions that is possible in a combination schedule for a given degree of effect as compared with the concentration of each drug alone as follows: (DRI)1 = (Dx)1/(D)1 and (DRI)2 = (Dx)2/(D)2. The DRI values for actual combination data points were calculated from the results obtained from CI equations (Chou et al., 1994).

Apoptosis

Treatment protocols were as for combination studies. At the end of experiments, cells harvested by trypsinization were combined with detached cells and apoptosis was analysed by the Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany), as recommended by the manufacturer.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were plated at a density of 1 × 105 cells·mL−1 in 100 mm Petri dishes (Sigma Aldrich) and treated with salbutamol plus rosiglitazone at 0.5 μM in a 1:1 ratio. Cells were harvested immediately after the end of drug exposure, washed twice with PBS and DNA was stained with propidium iodide (25 μg·mL−1), RNase (1 mg·mL−1) and Nonidet-P40 (0.1%). Samples were kept on ice for 30 min and cytofluorimetry was performed using a FACScan (Becton-Dickinson, San José, CA, USA). Data analysis was carried out with CELLQuest and ModWt software (Verity Software, Topsham, ME, USA).

Western blot analysis

Cells treated with combination 1:1 rosiglitazone and salbutamol at 0.5 μM for 48 h and untreated controls were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.4), and solubilized at 4°C for 45 min in lysis buffer [Tris base (50 mM), pH 7.6, EDTA (2 mM), NaCl (100 mM), Nonidet P40 (1%, v/v), PMSF (1 mM), aprotinin, pepstatin and antipain (2 μg·mL−1 each)]. The cell lysates were then centrifuged at 12 000 g for 10 min, and aliquots of the supernatants (50 μL of cytoplasmic proteins) were added with combination 1:1 of Laemmli sample buffer (50 mM Tris base, pH 6.8, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol and 0.025% β-mercaptoethanol) and separated with 12% SDS-PAGE. The membranes were then incubated overnight with monoclonal mouse anti-human primary antibodies directed against phospho-ERK1/2, total ERK or β-actin, and levels were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence after a 2 h incubation with a 1:2.000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody, followed by exposure to autoradiography film. The protein band intensities were quantified by densitometry.

Data analysis and statistics

All experiments were done in triplicate and data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Results were then plotted by Prism software (Graphpad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical analysis was carried out by one-way analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons. Densitometric assay of RT-PCR and Western blot bands was performed by using the ‘Quantity One’ softhware (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

Results

Evidence of PPARγ expression in BSMC

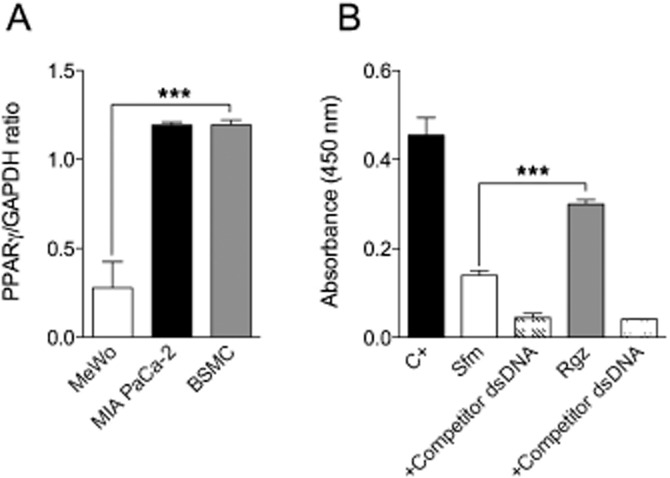

Real-time PCR analysis demonstrated that the PPARγ gene was expressed in BSMC at high levels, comparable with those of the housekeeping gene, GAPDH, and with those measured in MIA PaCa-2 cells (Figure 1A). The presence of functional PPARγ protein was also confirmed in serum-starved BSMC by ELISA, in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Real-time PCR assessment of PPARγ gene expression in different human cell lines (A) and analysis of DNA-binding activity of PPARγ in nuclear extracts of human BSMCs by ELISA (B). C+, positive control; Sfm, serum-free medium; Rgz, rosiglitazone. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001 (n = 3).

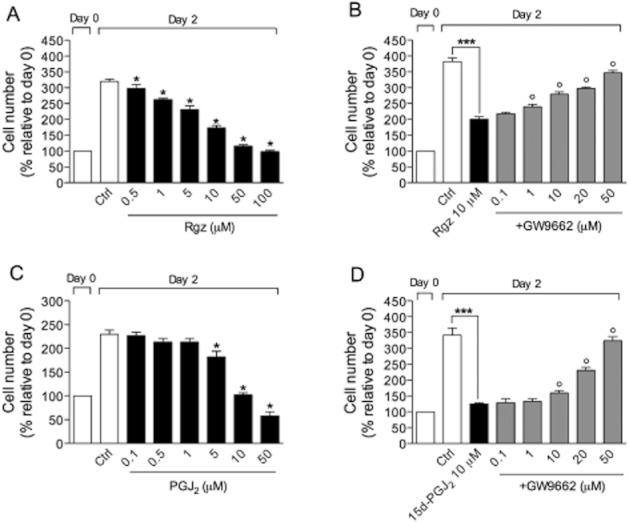

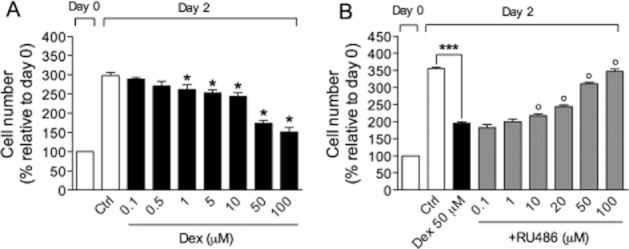

Effect of compounds on growth factor-stimulated BSMC growth

Antiproliferative effects induced by single agents were studied by exposing cells at different drug concentrations for 48 h. Stimulation of BSMC with growth factor-enriched medium promotes about fourfold increase in cell proliferation which was significantly prevented by rosiglitazone and PGJ2 in the micromolar range of concentrations (Figure 2A,C), with IC50 mean values of 8.5 ± 1.3 and 10.1 ± 1.4 μM, respectively. Such an effect was mediated by PPARγ as the selective antagonist, GW9662, dose-dependently reversed the antiproliferative action of compounds (Figure 2B,D).

Figure 2.

Antiproliferative effect of the PPARγ agonists, rosiglitazone (Rgz) and PGJ2, on growth factor-stimulated BSMC in the absence (A,C) or presence (B,D) of the selective PPARγ antagonist, GW9662. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, as compared with control (n = 3); °P < 0.05, compared with treatment with PPARγ agonist alone (n = 3).

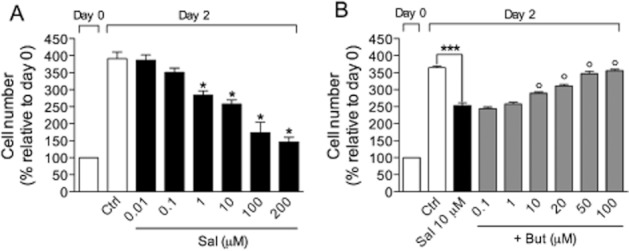

Salbutamol, tested in the same experimental conditions, could also prevent the growth factor-stimulated BMSC proliferation from 1 to 200 μM with an IC50 of 7.4 ± 1.8 μM (Figure 3A). Inhibition of cell proliferation induced by salbutamol was significantly reversed by the selective β2-adrenoceptor antagonist, butoxamine (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Antiproliferative effect of salbutamol (Sal) on growth factor-stimulated BSMC in the absence (A) or presence (B) of the selective β2-adrenoceptor antagonist, butoxamine (But). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, as compared with control (n = 3); °P < 0.05, compared with treatment with salbutamol alone (n = 3).

We used dexamethasone as reference compound as glucocorticoids have been reported to interact with β2-adrenoceptor agonists at the molecular level and synergistically prevent the accelerated growth of BSMC (Roth et al., 2002). As shown in Figure 4A, dexamethasone dose-dependently inhibited growth factor-stimulated BSMC proliferation (IC50 of 34.8 ± 1.6 μM). Co-treatment with the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, RU486, from 10 to 100 μM, prevented such an effect (Figure 4B), whereas RU486 alone did not affect cell proliferation (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Antiproliferative effect of dexamethasone (Dex) on growth factor-stimulated BSMC in the absence (A) or presence (B) of the glucocorticoid receptor antagonist, RU486. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, as compared with control (n = 3); °P < 0.05, compared with treatment with dexamethasone alone (n = 3).

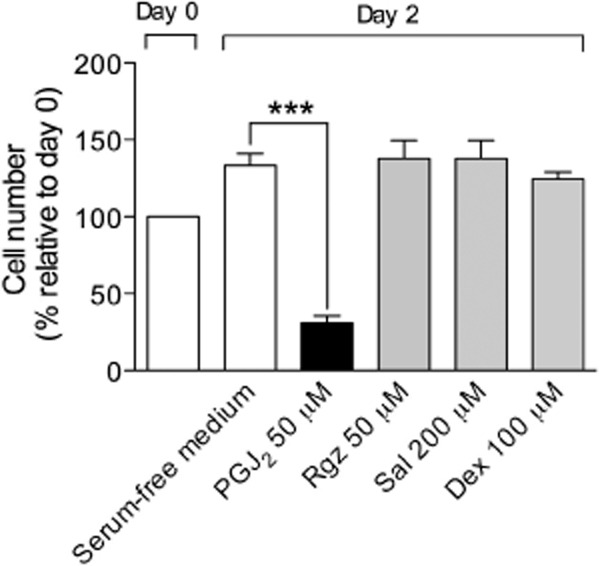

To clarify whether cytotoxicity could contribute to the reduced cell number observed after drug treatment, BSMCs cultured in a growth factor-free medium containing only 5% FBS as a supplement were exposed to compounds at the highest concentrations tested in cell growth inhibition assay. In these conditions, BSMC proliferation was lower than that observed in growth factor-enriched cultures (about 1.3-fold increase in cell number relative to day 0) (Figure 5). Interestingly, after 48 h exposure, all compounds did not significantly change cell number, as compared with control (Figure 5), and cell viability assessed by Trypan blue exclusion method was unaffected by treatments (data not shown), suggesting that these compounds function by a cytostatic mechanism. The mechanism of action of compounds may also depend on the concentration level tested, as the endogenous PPARγ ligand PGJ2 was cytotoxic at 50 μM (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of compounds at the highest concentrations tested in cell growth inhibition assay on BSMC cultured in a growth factor-free medium containing 5% FBS. Rgz, rosiglitazone; Sal, salbutamol; Dex, dexamethasone. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001, compared with control (n = 3).

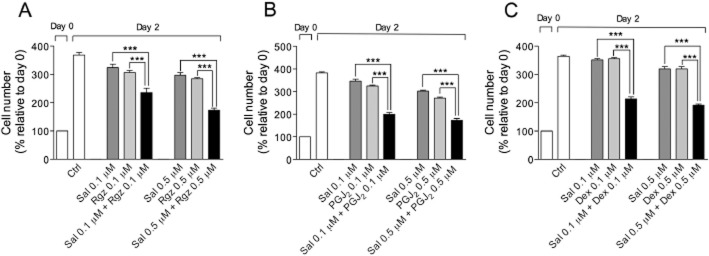

Synergistic interaction between PPARγ agonists and salbutamol

Single-agent concentration-response curves allowed us to calculate parameters (e.g. IC50 mean values and coefficients signifying the shape of the dose-effect curves) that serve for combination study design. The combination of salbutamol with rosiglitazone or PGJ2 at low concentrations (0.1 and 0.5 μM) produced an effect greater than that of each drug alone (Figure 6A,B) and the quantitative CI method demonstrated the presence of a synergistic interaction between drugs (i.e. CI < 1) (Table 1). As expected, the combination of salbutamol and dexamethasone also synergistically reduced growth factor-stimulated BSMC growth after 48 h (Figure 6C; Table 1).

Figure 6.

Antiproliferative effect of salbutamol (Sal), rosiglitazone (Rgz), PGJ2 and dexamethasone (Dex), alone or in combination schedules, on growth factor-stimulated BSMC. All data are mean ± SEM). ***P < 0.001, significant difference from the effects with each drug alone (n = 3).

Table 1.

Combination Index (CI) and Dose Reduction Index (DRI) values for salbutamol in combination with PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone after 48 h on human BSMC

| Compounds (μM) | GI (%) | CI | DRI | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sal | Rgz | PGJ2 | Dex | Sal | Rgz | PGJ2 | Dex | ||||||||

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 36 ± 5.5 | 0.66 ± 0.1 | 4.7 ± 2.3 | 5.5 ± 1.8 | ||||||||||

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 53 ± 3.1 | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 3.5 ± 0.85 | ||||||||||

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 48 ± 1.5 | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 12.9 ± 2.2 | 10.2 ± 0.8 | ||||||||||

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 55 ± 2.1 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 6.4 ± 1.7 | 3 ± 0.3 | ||||||||||

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 42 ± 2.25 | 0.29 ± 0.08 | 6.2 ± 1.4 | 10.2 ± 1.9 | ||||||||||

| 0.5 | 0.5 | 48 ± 0.57 | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | ||||||||||

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3). CI < 1, CI = 1, and CI > 1 indicate synergism, additive effect and antagonism respectively.

GI, growth inhibition; Sal, salbutamol; Rgz, rosiglitazone; Dex, dexamethasone.

The DRI represents the fold of dose reduction allowed in a combination (for a given degree of effect) as compared with the dose of each drug alone. Combinations between salbutamol and PPARγ agonists allow obtaining approximately the 50% growth inhibition at concentrations from 2.3 to 12.4-fold lower than those required for each drug alone (Table 1).

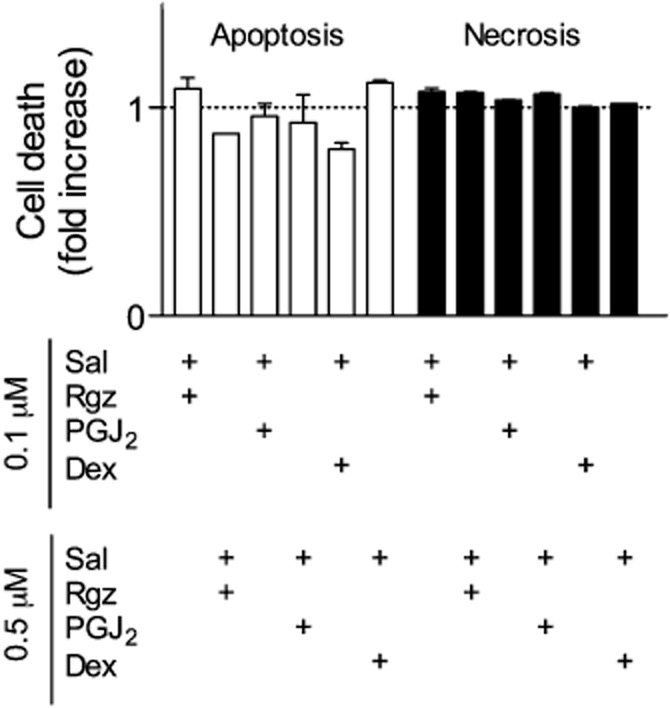

To investigate whether a switch from cytostatic to cytotoxic effects could account for synergism of combination schedules, we performed experiments aimed at evaluating the extent of accumulation of histone-complexed DNA fragments in the cytoplasmic fraction (apoptosis) or directly in the culture supernatant (necrosis). Noteworthy, combinations of salbutamol with PPARγ agonists or dexamethasone did not significantly induce cell death (Figure 7), suggesting that synergism was most probably caused by a more pronounced cytostatic effect than that induced by single treatments.

Figure 7.

Absence of apoptosis and necrosis after treatment of BSMC with different drug combinations at concentrations that caused a 50% inhibition of cell growth. Rgz, rosiglitazone; Sal, salbutamol; Dex, dexamethasone. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3).

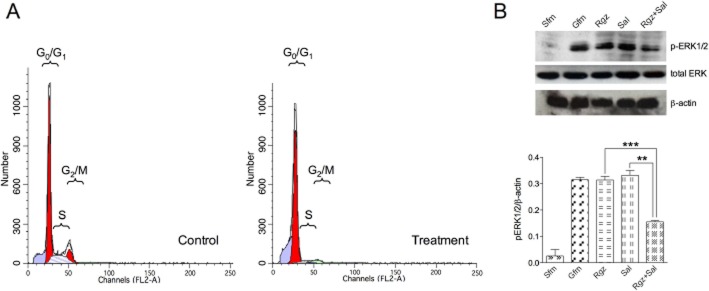

Effect of rosiglitazone plus salbutamol on cell cycle distribution and mitogen-induced ERK activation

To further elucidate the mechanism of drug combination, we studied possible changes in cell cycle regulation after treatment with salbutamol + rosiglitazone (0.5 μM) in a 1:1 ratio. In BSMC stimulated with growth factor-enriched medium (control), the proportion of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle was 71.4, 17.3 and 11.3% respectively (Figure 8A). The percentage of S-phase and G2/M-phase cells was considerably decreased (1.86 and 0% total events) by the presence of the combination treatment. The parallel increase in the proportion of cells in G0/G1 phase in treated (98.1% total events) versus untreated cells suggest a cell cycle arrest at this level of the cell cycle (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

(A) Effect of salbutamol + rosiglitazone 0.5 μM at the fixed ratio of 1:1 on the distribution of events in the cell cycle. (B) The phosphorylation of ERK1/2 protein in BSMC treated with 0.5 μM salbutamol or rosiglitazone, alone and in combination with each other (the images were analysed by densitometry). Sfm, serum-free medium; Gfm, growth factor-enriched medium; Rgz, rosiglitazone; Sal, salbutamol.

Growth factor-induced ERK1/2 activation in BSMC occurred within 2 min and it was characterized by a 12-fold increase in protein phosphorylation, as compared with unstimulated cells (Figure 8B). While rosiglitazone or salbutamol alone did not exert any effect, combination treatment at 0.5 μM significantly reduced (P < 0.001) ERK phosphorylation by 50%, as compared with cells cultured in growth factor-enriched medium (Figure 8B).

Discussion

Severe asthma is characterized by airway remodelling due, in part, to increases in airway smooth muscle mass (Hirst et al., 2000; Bentley and Hershenson, 2008; Jarjour et al., 2012). Combination treatments represent the most commonly used therapeutic strategy in patients with severe disease; however, clinical trials of combination therapy are frequently conducted empirically in the absence of supporting experimental data, especially for new drugs. In our opinion, the method used in this study may represent a useful approach for rational clinical protocol design of novel anti-remodelling drug combinations. Specifically, we carried out an in vitro drug combination study to determine the real synergism between PPARγ agonists and the β2-adrenoceptor agonist, salbutamol, on human BSMC proliferation stimulated by growth factors, as cellular model of airway remodelling. We used the CI method, a quantitative analysis that takes into account both the potency of each drug and combinations of these drugs and the shapes of their dose-effect curves (Chou et al., 1994). Our findings demonstrated, for the first time, that combination of these two drug classes at sub-micromolar concentrations synergistically inhibited mitogen-induced BSMC proliferation. We have also quantified the dose reduction for the component drugs, showing that combination schedules allowed the salbutamol and PPARγ agonist concentrations to be decreased by about 2 to 12-fold compared with single agents, while maintaining drug effect. This information appears to be clinically relevant because, as a general rule, dose reduction (due to efficacy synergy) always leads to reduction in toxicity, therefore improving overall therapeutic results.

Another relevant finding of the present study is that the synergistic effect induced by PPARγ agonists + salbutamol was comparable with that observed for the combination dexamethasone + salbutamol, suggesting that PPARγ agonists might be used instead of steroids to design β2-adrenoceptor agonist-based combination schedules in steroid-resistant airway diseases. In support of this proposal, rosiglitazone produced improvements in lung function in smokers with asthma, showing a reduced response to inhaled corticosteroids (Spears et al., 2009), and preserved airway smooth muscle responsiveness to salbutamol following homologous desensitization (Fogli et al., 2011).

Several lines of evidence supporting the potential combined benefit of PPARγ agonists and corticosteroids currently used in the treatment of chronic lung diseases are also important from the clinical and pharmacological point of view. For example, corticosteroids can favourably interact with PPARγ agonists by reducing IL-1β-induced COX-2 expression (Pang et al., 2003) and TNFα-induced production of chemokines (Nie et al., 2005) in human BSMCs. Furthermore, the glucocorticoid budesonide induced PPARγ expression in sputum cells of patients with COPD (Holownia et al., 2008), a condition that may increase cell responsiveness to PPARγ ligands. Finally, it is worth mentioning that in some steroid-insensitive subjects, glucocorticoid receptors are unable to translocate to the nucleus, as a result of MAPK-induced phosphorylation, and steroids are thereby ineffective (Adcock and Lane, 2003). In the present study, we demonstrated that the combination of salbutamol with the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone strongly inhibited MAPK/ERK phosphorylation and may have potential in reversing glucocorticoid insensitivity.

Single-agent experiments were required to calculate parameters used in combination studies in order to achieve a high level of accuracy in CI analyses. Furthermore, we assessed the inhibitory potency of compounds in a cellular model that mimics a clinical condition of steroid resistance (dexamethasone IC50 > 1 μM) and demonstrated that salbutamol and PPARγ agonists were able to inhibit human BSMC growth at clinically relevant concentrations in this experimental setting. The current finding that PPARγ ligands inhibited proliferative responses induced by the specific mitogens that have been found elevated in the airways of asthmatic patients (Hirst et al., 2000; Bentley and Hershenson, 2008) supports the anti-remodelling potential of these compounds. With regard to the molecular mechanism of action, the role of PPARγ in the antiproliferative effects of PGJ2 and rosiglitazone observed in the present study was investigated using the selective and irreversible antagonist of the PPARγ receptor, GW9662 (Leesnitzer et al., 2002). IC50 values for PPARγ agonists were in the micromolar range and the concentration-dependent reversal of the rosiglitazone or PGJ2-mediated inhibition of mitogen-induced proliferation by GW9662 provided evidence that the antimitogenic action of PPARγ agonists in human BSMCs was PPARγ-dependent. In line with these results, rosiglitazone inhibited serum-induced growth in human pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells with potency (IC50) of 35–45 μM and such an effect was PPARγ-dependent (Falcetti et al., 2010). The effect of GW9662 (1 μM) on the growth inhibition induced by rosiglitazone (10 μM) observed in our study was comparable with that obtained by Ward and co-workers (2004) in BSMCs stimulated by thrombin. The almost complete reversal by 1 μM GW9662 reported by Ward and co-workers appeared to be in contrast with the partial reversal observed in our study. However, this apparent discrepancy is mainly due to the difference between the maximum stimulatory effects induced by thrombin-enriched media (Ward et al., 2004) and multiple growth factor stimulation (our study). In line with this notion, we showed that higher GW9662 concentrations completely reduced the antimitogenic potential of both rosiglitazone and PGJ2, supporting a crucial role for PPARγ also in this experimental setting.

Our results also clearly confirm previously reported findings showing that single-agent salbutamol, through activation of β2-adrenoceptors, has a direct inhibitory effect on the proliferation of human BSMCs elicited by growth factors at clinically relevant concentrations, with no evidence of cytotoxicity (Tomlinson et al., 1994; Stewart et al., 1997; 1999). The molecular mechanism involved in the antiproliferative action of β2-adrenoceptor agonists in BSMCs is not fully understood. For example, while the action of these drugs is considered to be dependent largely on increase in intracellular cAMP levels, the antimitogenic effects of cAMP involve multiple mechanisms, including inhibition of ERK1/2 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase, via PKA activation and/or Epac in BSMCs (Billington et al., 2012). Furthermore, there is controversy concerning the specific role played by each of these signalling pathways (Kassel et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2011).

In our study, dexamethasone inhibited growth of human BSMCs cultured in a specific growth factor-enriched medium by 50% at micromolar concentrations, an experimental condition that can be considered to mimic steroid resistance (De et al., 2002). Although establishing the effect of multiple growth factor stimulation on the antiproliferative response to corticosteroids in BSMCs was beyond the scope of the current study, several lines of evidence suggest that corticosteroids may not be effective in inhibiting BSMC mitogenesis in response to receptor tyrosine kinase-activating mitogens (Panettieri, 2004; Wang et al., 2006). Therefore, our cellular model mimics a clinical condition of corticosteroid resistance, that is, low responses to steroid and clear evidence of airway remodelling, as recently observed in patients with severe asthma (Bourdin et al., 2012).

In the current study, the mechanism of the enhanced reduction in cell number following salbutamol plus PPARγ agonists was further explored to determine whether these combinations were causing cell death or inhibiting BSMC proliferation. Such a pharmacological property appears to be important especially in patients with severe long-standing asthma or COPD in which the turnover rates of human BSMCs are most probably higher than in normal subjects (Barnes, 2009). As we could not find evidence for induction of BSMC cytotoxicity or apoptosis, it is conceivable that combinations of these two drug classes can effectively reduce airway smooth muscle hyperplasia without affecting tissue integrity, in chronic patients. The cytostatic effect of salbutamol + PPARγ agonist combination is also supported by our finding a cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.

The present study emphasize the quantitative end results of drug combinations rather than the molecular mechanism underlying the synergistic interaction that remains to be clarified. An interesting point that should be considered in this regard comes from recently published findings showing that homologous β2-adrenoceptor desensitization induced by exposing BSMCs to salbutamol 1 μM for 24 h (i.e. a condition similar to that used in combination studies) significantly increased nuclear PPARγ translocation (Fogli et al., 2011). Such a mechanism might account for a more effective antiproliferative effect of the combined drugs compared with each drug alone due to the sensitizing effect of salbutamol on the PPARγ agonist-induced cell growth inhibition. Compatible with such a mechanism, fenoterol at 0.1 μM for 15 h has been demonstrated to up-regulate the mRNA expression of PPARγ in cultured epithelial cells (Faisy et al., 2010), suggesting that such an effect is independent of cell type.

It is widely recognized that prolonged in vitro exposure to salbutamol causes tolerance (as a consequence of homologous β2-adrenoceptor desensitization), which became evident at the cellular level after 24 h through the reduced ability of the β2-adrenoceptor agonist to promote cAMP synthesis (Düringer et al., 2009; Fogli et al., 2011). As β2-adrenoceptor agonists affect cell proliferation by increasing cAMP (Tomlinson et al., 1994), it could be that homologous β2-adrenoceptor desensitization abolished the inhibitory effect of β2-adrenoceptor agonists, therefore limiting their anti-remodelling potential. We have previously demonstrated that the PPARγ agonists, rosiglitazone and PGJ2, reverse salbutamol-induced tolerance in homologously desensitized BSMC, restoring cAMP synthesis to a level comparable with that of control (Fogli et al., 2011), a property that could preserve the antiproliferative action of β2-adrenoceptor agonists. However, such an effect occurred at a concentration 20-fold higher than that used in combination experiments and it is unlikely that this mechanism could account for the synergistic interaction observed in the present study.

In conclusion, our findings provide the first evidence of the synergistic interaction between PPARγ agonists and β2-adrenoceptor agonists on BSMC proliferation. The combination of these two drug classes might therefore be considered in patients with severe asthma who do not respond adequately to corticosteroid therapy.

Glossary

- BSMC

bronchial smooth muscle cell

- bFGF

basic fibroblast growth factor

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Adcock IM, Lane SJ. Corticosteroid-insensitive asthma: molecular mechanisms. J Endocrinol. 2003;178:347–355. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1780347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammit AJ, Panettieri RA., Jr Airway smooth muscle cell hyperplasia: a therapeutic target in airway remodeling in asthma? Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2003;5:49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Corticosteroids. In: Barnes PJ, Drazen JM, Rennard SI, Thompson NC, editors. Asthma and COPD. San Diego: Elsevier Science; 2009. pp. 639–654. [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi MG, Mitchell JA. Targeting PPAR receptors in the airway for the treatment of inflammatory lung disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:994–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00373.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley JK, Hershenson MB. Airway smooth muscle growth in asthma: proliferation, hypertrophy, and migration. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:89–96. doi: 10.1513/pats.200705-063VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billington CK, Ojo OO, Penn RB, Ito S. cAMP regulation of airway smooth muscle function. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2012.05.007. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdin A, Kleis S, Chakra M, Vachier I, Paganin F, Godard P, et al. Limited short-term steroid responsiveness is associated with thickening of bronchial basement membrane in severe asthma. Chest. 2012;141:1504–1511. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TC, Motzer RJ, Tong Y, Bosl GJ. Computerized quantitation of synergism and antagonism of taxol, topotecan, and cisplatin against human teratocarcinoma cell growth: a rational approach to clinical protocol design. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1517–1524. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.20.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De A, Blotta HM, Mamoni RL, Louzada P, Bertolo MB, Foss NT, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on lymphocyte proliferation and cytokine production in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning GM, Stoll LL. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: potential therapeutic targets in lung disease? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006;41:23–34. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Düringer C, Grundström G, Gürcan E, Dainty IA, Lawson M, Korn SH, et al. Agonist-specific patterns of beta 2-adrenoceptor responses in human airway cells during prolonged exposure. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:169–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisy C, Pinto FM, Blouquit-Laye S, Danel C, Naline E, Buenestado A, et al. beta2-Agonist modulates epithelial gene expression involved in the T- and B-cell chemotaxis and induces airway sensitization in human isolated bronchi. Pharmacol Res. 2010;61:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcetti E, Hall SM, Phillips PG, Patel J, Morrell NW, Haworth SG, et al. Smooth muscle proliferation and role of the prostacyclin (IP) receptor in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1161–1170. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0011OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firszt R, Kraft M. Pharmacotherapy of severe asthma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:266–271. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogli S, Pellegrini S, Adinolfi B, Mariotti V, Melissari E, Betti L, et al. Rosiglitazone reverses salbutamol-induced β(2) -adrenoceptor tolerance in airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:378–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M, Jo T, Risse PA, Tolloczko B, Lemière C, Olivenstein R, et al. Airway smooth muscle remodeling is a dynamic process in severe long-standing asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1037–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst SJ, Walker TR, Chilvers ER. Phenotypic diversity and molecular mechanisms of airway smooth muscle proliferation in asthma. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:159–177. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a28.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holownia A, Mroz RM, Noparlik J, Chyczewska E, Braszko JJ. Expression of CREB-binding protein and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma during formoterol or formoterol and corticosteroid therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl. 6):303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarjour NN, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Comhair SA, et al. Severe asthma: lessons learned from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:356–362. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel KM, Wyatt TA, Panettieri RA, Jr, Toews ML. Inhibition of human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation by beta 2-adrenergic receptors and cAMP is PKA independent: evidence for EPAC involvement. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L131–L138. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00381.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leesnitzer LM, Parks DJ, Bledsoe RK, Cobb JE, Collins JL, Consler TG, et al. Functional consequences of cysteine modification in the ligand binding sites of peroxisome proliferator activated receptors by GW9662. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6640–6650. doi: 10.1021/bi0159581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M, Corbett L, Knox AJ, Pang L. Differential regulation of chemokine expression by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists: interactions with glucocorticoids and beta2-agonists. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2550–2561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410616200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner DE. Clinical practice. Outpatient management of severe COPD. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1407–1416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0912556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panettieri RA., Jr Effects of corticosteroids on structural cells in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2004;1:231–234. doi: 10.1513/pats.200402-021MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang L, Nie M, Corbett L, Knox AJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in human airway smooth muscle cells: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. J Immunol. 2003;170:1043–1051. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.2.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfrey H, Farahi N, Porter L, Chilvers ER. Live and let die: is neutrophil apoptosis defective in severe asthma? Thorax. 2010;65:665–667. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.134270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth M, Johnson PR, Rüdiger JJ, King GG, Ge Q, Burgess JK, et al. Interaction between glucocorticoids and beta2 agonists on bronchial airway smooth muscle cells through synchronised cellular signalling. Lancet. 2002;360:1293–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears M, Donnelly I, Jolly L, Brannigan M, Ito K, McSharry C, et al. Bronchodilatory effect of the PPAR-gamma agonist rosiglitazone in smokers with asthma. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86:49–53. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AG, Tomlinson PR, Wilson JW. Beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist-mediated inhibition of human airway smooth muscle cell proliferation: importance of the duration of beta 2-adrenoceptor stimulation. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:361–368. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AG, Harris T, Fernandes DJ, Schachte LC, Koutsoubos V, Guida E, et al. Beta2-adrenergic receptor agonists and cAMP arrest human cultured airway smooth muscle cells in the G(1) phase of the cell cycle: role of proteasome degradation of cyclin D1. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;56:1079–1086. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarayan V, Xu XC, Kim J, Yang P, Hoque A, Sabichi AL, et al. Inverse relationship between 15-lipoxygenase-2 and PPAR-gamma gene expression in normal epithelia compared with tumor epithelia. Neoplasia. 2005;7:280–293. doi: 10.1593/neo.04457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson PR, Wilson JW, Stewart AG. Inhibition by salbutamol of the proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells grown in culture. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;111:641–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hayashi J, Serrero G. PC cell-derived growth factor confers resistance to dexamethasone and promotes tumorigenesis in human multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:49–56. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward JE, Gould H, Harris T, Bonacci JV, Stewart AG. PPAR gamma ligands, 15-deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 and rosiglitazone regulate human cultured airway smooth muscle proliferation through different mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141:517–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H, Deshpande DA, Misior AM, Miles MC, Saxena H, Riemer EC, et al. Anti-mitogenic effects of β-agonists and PGE2 on airway smooth muscle are PKA dependent. FASEB J. 2011;25:389–397. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-164798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]