Abstract

The cytokine thrombopoietin (TPO), the ligand for the hematopoietic receptor c-Mpl, acts as a primary regulator of megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production. We have determined the crystal structure of the receptor-binding domain of human TPO (hTPO163) to a 2.5-Å resolution by complexation with a neutralizing Fab fragment. The backbone structure of hTPO163 has an antiparallel four-helix bundle fold. The neutralizing Fab mainly recognizes the C–D crossover loop containing the species invariant residue Q111. Titration calorimetric experiments show that hTPO163 interacts with soluble c-Mpl containing the extracellular cytokine receptor homology domains with 1:2 stoichiometry with the binding constants of 3.3 × 109 M–1 and 1.1 × 106 M–1. The presence of the neutralizing Fab did not inhibit binding of hTPO163 to soluble c-Mpl fragments, but the lower-affinity binding disappeared. Together with prior genetic data, these define the structure–function relationships in TPO and the activation scheme of c-Mpl.

More than 40 years ago Keleman et al. (1) predicted the existence of a potent, lineage-specific soluble factor, which they called thrombopoietin (TPO), that stimulates megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production. It was not until 1994 that unequivocal evidence for the existence of this elusive molecule was provided by the nearly simultaneous isolation and cloning of TPO by five independent research groups (2–6). This cytokine has proven to be a primary factor in megakaryocytopoiesis from megakaryocyte colony formation to platelet production and the differentiation and proliferation of progenitor cells of multiple hematopoietic lineages (7). As such, TPO is being investigated for its potential to treat thrombocytopenia resulting from AIDS and chemotherapy and radiation treatments for cancer and leukemia and for the in vivo and ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic stem cells for bone marrow transplantation.

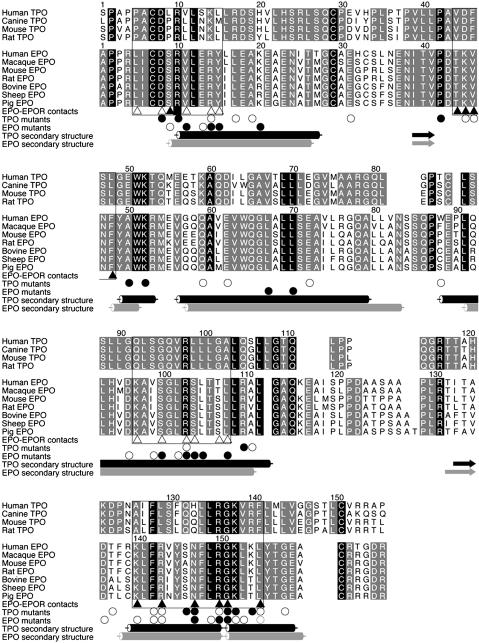

Human TPO (hTPO) is a heavily glycosylated protein with two distinct regions. The 153-residue N-terminal region is homologous to human erythropoietin (EPO) with which it shares 23% sequence identity and is sufficient for receptor binding and signal transduction (2, 3, 8). The 179-residue C-terminal region has a large number of proline and glycine residues and six N-linked glycosylation sites. Its function is not known, although recent work indicates a role in secretion and protection from proteolysis (9, 10).

The TPO receptor c-Mpl was first identified as an oncogene of the murine myeloproliferative leukemia virus (11, 12) that was able to immortalize hematopoietic progenitor cells and was later cloned from human and mouse (13, 14). c-Mpl is expressed in some pluripotent hematopoietic stem cells (15) and in the megakaryocyte lineage from progenitor cells to platelets (16). It is a class I cytokine receptor of the hematopoietic superfamily of receptors and signals by the JAK/STAT, Ras, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways (17–21). Class I hematopoietic receptors bind to their cytokine ligands by ≈200-aa Ig-like extracellular domains called cytokine receptor homology (CRH) or hematopoietic receptor domains that contain a distinctive WSXWS sequence motif (13).

Cytokines possess two distinct interaction sites that bind with differing affinities [high affinity (nanomolar range) and low affinity (micromolar range)] to the same cytokine-recognition surface of the CRH domain. Crystal structures of human EPO and human growth hormone (hGH) in complex with the extracellular CRH domains of their receptors (22, 23) have shown the cytokine–CRH interaction in detail. However, unlike EPO receptor (EPOR) and hGH receptor (hGHR), which have only one CRH domain, c-Mpl belongs to a subset of hematopoietic receptors whose extracellular region contains two CRH domains (24, 25), each with an WSXWS motif. To determine the tertiary structure of the receptor-binding domain of TPO (hTPO163), an antibody fragment of the TN1-neutralizing IgG was exploited to crystallize hTPO163. This approach not only produced diffraction-quality crystals of this cytokine, which has resisted crystallization for many years, but the TN1-Fab provided enough phase information to solve the structure from a single data set. This approach resulted in readily traceable and completely unbiased electron density maps for hTPO163. Finally, we have succeeded in determination of the tertiary structure of the important cytokine TPO. Our structural results have been used to interpret previously published functional data on TPO; however, the interaction scheme between the multiple CRH domains of c-Mpl and TPO remains to be fully determined.

Materials and Methods

Materials. The hTPO gene (26) containing the N-terminal region from residues 1 to 163 (hTPO163) was expressed in Escherichia coli and prepared as reported (27). The TN1-neutralizing IgG (subclass IgG1) was raised against recombinant hTPO (28) and prepared by hybridoma cultivation followed by affinity chromatography with a protein G agarose column (Amersham Pharmacia Biosciences). The TN1-IgG showed half-maximal binding at 0.7 nM against 3.3 pmol of hTPO in ELISAs. In cell-proliferation assays, TN1 inhibited hTPO-dependent growth of FDCP-2 cells expressing human c-Mpl by 98%, indicating that binding of TN1 severely disrupted activation of c-Mpl signaling by hTPO (27). The extracellular region of c-Mpl containing residues 1–450 was obtained from the Pharmaceutical Division of the Kirin Brewery Company.

Structure Determination. Crystals in two different forms were obtained as described (27) by using a nonglycosylated form of hTPO163, and the Fab was derived from TN1. Both crystals were extremely sensitive to x-ray exposure, necessitating the use of flash-freezing and synchrotron radiation for data collection. Two complete data sets with the space groups P21 and C2 were collected by using synchrotron radiation (Table 1).

Table 1. Data collection statistics.

| Crystal | Form I | Form II |

|---|---|---|

| Space group | P21 | C2 |

| Unit cell | a = 133.20 | a = 131.71 |

| b = 46.71 | b = 46.48 | |

| c = 191.47 | c = 184.63 | |

| β = 90.24 | β = 90.42 | |

| Resolution, Å | 60-3.3 | 60-2.5 |

| Observations used in scaling | 74,809 | 120,117 |

| Unique reflections | 35,598 | 36,766 |

| Mean (I/σI) overall | 3.0 | 8.1 |

| (highest shell) | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Completeness for F/σF > 2.0, % | 98 | 92 |

| (highest shell) | 97 | 71 |

| Multiplicity | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| Mosaicity | 0.412 | 0.637 |

| R merge, % | 9.8 | 7.4 |

| (highest shell) | 21.4 | 31.8 |

Diffraction data of the P21 and C2 forms were collected at the BL6B (Photon Factory) on image plates and at the BL41XU (SPring-8) on a charge-coupled device camera by using 1.00-Å radiation from a single crystal flash-frozen at 100 K with 8% glycerol as cryoprotectant, respectively. Data to 2.8 and 2.5 Å were reduced in space groups P21 and C2 by using denzo/scalepack (53).

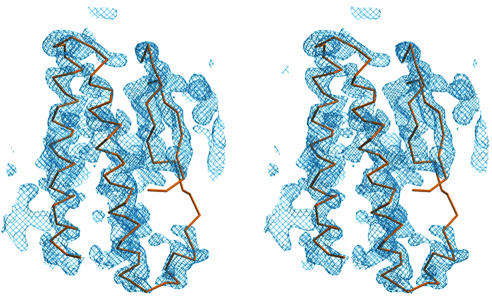

Molecular replacement with amore (29) by using coordinates of known Fab structures obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (30) located four sites in the asymmetric unit for the P21 data set, as expected based on specific volume calculations (31). This solution, with PDB coordinate 1IAI (32), was rigid-body-refined to an R factor of 45.8% with TNT (33). By using the known relationship between the four Fab molecules, the electron density could be improved by 4-fold averaging. The 2FO–FC difference Fourier omit maps spanning the entire molecule were calculated after solvent flattening, histogram matching, and 4-fold improper noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) averaging with dm (34). The TN1-Fab coordinates were rebuilt by using quanta98 (Accelrys, San Diego) and refined with restrained NCS averaging to an R factor of 28.5%. The hTPO163 region was phased by solvent flattening and histogram matching with σA-weighted (35) initial phases from the refined TN1-Fab coordinates followed by NCS averaging by using maprot (36) without an averaging mask. A conservative estimate of the solvent content of 25% gave the best results (the calculated value was ≈45%). The resulting unbiased density shown in Fig. 1 was easily traced for 115 residues of hTPO163, including all four α-helices and both β-strands. The sequence was assigned by locating the density of the C29—C85 disulfide bond and several aromatic residues. Residues 1–6 and 152–163 could not be distinguished in electron density maps and were omitted from the model. The completed model was refined with refmac (37) using NCS restraints, and the data were truncated to 2.9 Å for final refinement by using R factor vs. resolution and σA as a guide. Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank with PDB ID code 1V7N.

Fig. 1.

Initial electron density of hTPO163 calculated at 2.8 Å and contoured at 1.25 σ. σA-Weighted electron density is calculated after solvent flattening, histogram matching, and NCS averaging. The Cα trace for residues 35–123 of the final refined model is overlaid only as a guide.

The refined atomic coordinates were used as the initial model for crystallographic refinement in space group C2 data. The arrangement of the molecules in the asymmetric unit was determined with amore (28). The cell dimensions and crystal packing of the P21 and C2 crystal forms are in fact nearly identical. A slight disruption of the translational component of the C2 symmetry results in a crystal form with P21 symmetry and a doubling of the size of the asymmetric unit. The atomic model in C2 crystal was refined to an R factor of 0.227–2.5 Å resolution by using cnx (Accelrys) and refmac (37). The refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2. The refined coordinates have also been deposited in the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank with PDB ID code 1V7M.

Table 2. Summary of refinement statistics.

| Crystal | Form I | Form II |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution used, Å | 15-3.3 | 15.0-2.5 |

| No. of atoms | 17,572 | 8,910 |

| Protein | 17,408 | 8,754 |

| Water | 164 | 156 |

| Rwork* | ||

| Overall | 0.170 | 0.227 |

| Highest shell | 0.181 | 0.283 |

| Rfree† | ||

| Overall | 0.292 | 0.315 |

| Highest shell | 0.374 | 0.355 |

| Average B factors, overall, Å2 | 33.0 | 50.3 |

| rms deviations from ideality | ||

| Bond length, Å | 0.028 | 0.020 |

| Bond angles, Å | 2.8 | 2.0 |

Rwork = ΣΣ||Fobs| — |Fcalc||/ΣΣ|Fobs|, where Fobs and Fcalc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree is the same as Rwork but for a 5% subset of all reflections.

Affinity of TPO to c-Mpl in the Absence and Presence of TN1-Fab. The association constants were determined by using an MCS titration calorimeter (Microcal Software, Northampton, MA). Of soluble c-Mpl (9.3 μM), ≈1.5 ml was titrated by 10-μl portions of hTPO163 (143 μM) in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 100 mM NaCl at 25°C. Moreover, the same amount of soluble c-Mpl (9.3 μM) was titrated by hTPO163 (120 μM) that had been preincubated with the same amount of TN1-Fab to investigate the effect of neutralization. The association constants were determined by analyzing the titration curves with the program origin (Microcal Software). The end points of titration curves, where the heat signal disappears, directly give us the stoichiometry because the concentration of both samples had already been determined.

Results

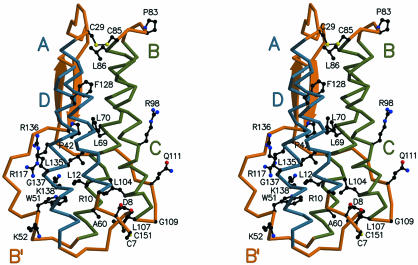

Tertiary Structure of TPO. The receptor-binding domain of hTPO is a four-helix bundle with up-up-down-down topology (Fig. 2). Left-handed crossovers between the A and B and the C and D helices form an antiparallel β-sheet (residues 39–43 and 117–121) that packs against the B and D helices. The A–B crossover forms a small helix B′ from residues 49–53. The helical pair interactions are parallel (A/D and B/C pairs) with the acute angles between pairs of helices ranging from 11° to 24°. The skew angle between the A/D and B/C layers of helix pairs is ≈16°. A bend of ≈20° is notable in helix D at G137. The C terminus of helix A and the N terminus of helix C are bridged by a disulfide bond between C29 and C85. Another disulfide bond between C7 and C151, which links the N- and C-terminal regions of the four-helix bundle, is essential for biological function (38–40).

Fig. 2.

Determinants of the structural frame of hTPO163. Stereoviews of the secondary structure show the up-up-down-down topology. Residues that are invariant in the TPO/EPO family are shown in black. Labels indicate the helices of the four-helix bundle (A, B, C, and D) and the minihelix B′. The A/D and B/C helix pairs are shown in blue and green.

hTPO possesses the same combination of features from long-chain and short-chain cytokines observed by NMR (41) and crystallography (42) for human EPO. The length and interhelical packing of the four-helix bundle is characteristic of the long-chain variety of cytokines, whereas the topology and secondary structure in the crossover loops is characteristic of the short-chain variety. In long-chain cytokines it is characteristic for the A–B crossover to pass over the C–D crossover. However, in TPO the A–B crossover passes beneath the C–D crossover, which is characteristic of short-chain cytokines. The antiparallel β-strands formed by the crossovers and the small B′ helix in the A–B crossover are also more characteristic of short-chain than long-chain cytokines. The structural similarities and high degree of sequence homology between TPO and EPO stand in contrast to their exquisite specificity for their receptors. This structure may then be a guide for designing and interpreting mutagenic experiments and is an important step forward in designing TPO variants and fragments that will be efficacious therapeutics for thrombocytopenia.

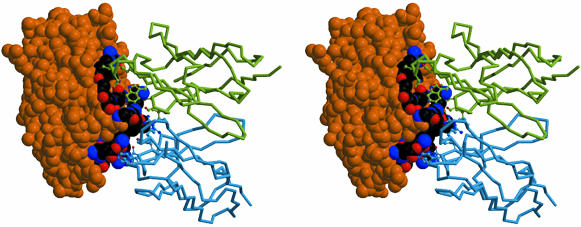

TN1 Recognition Epitope. The antibody recognition epitope (Fig. 3) consists of residues from the C-terminal end of helix C (R98) and the C–D crossover loop (residues 102–115) and residues from the C-terminal half of helix B (residues 57–61). This result, which was in good agreement with the analysis of its interaction with proteolytic fragments of hTPO, localized the neutralizing epitope within residues 60–117 (27). The change in accessible surface area for complex formation is 799 Å2 for hTPO163 and 777 Å2 for TN1. The interactions consist of nine apparent hydrogen bonds but no apparent bridging water molecules. One notable hydrophobic contact occurs among TPO P113 and light chain Y48 and heavy chain L104. The most striking feature of the interface is the interaction of the species-invariant residue Q111, which inserts in a sandwich-like manner between the indole rings of W33 and W101 of the Fab heavy chain to form a hydrogen bond with the backbone carbonyl of W33.

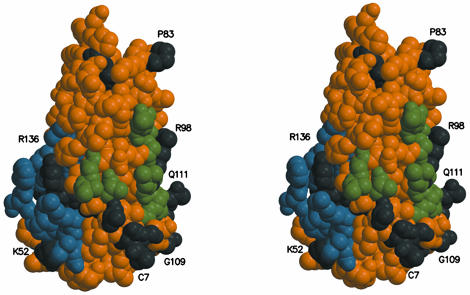

Fig. 3.

hTPO163–TN1-Fab complex. The Cα traces for the heavy and light chains of the variable domains of the TN1-Fab are shown in green and blue. Only residues that interact with hTPO163 are shown. hTPO163 is shown in the Corey–Pauling–Koltun molecular model (CPK) with residues that interact with the TN1-Fab highlighted as individually colored CPK atoms. Regions of hTPO163 that do not interact with the TN1-Fab are shown as solid orange CPK.

Interaction Between TPO and c-Mpl in the Absence and Presence of the TN1-Fab. The hTPO163–c-Mpl interaction and the neutralizing effect of TN1 were explored by isothermal titration calorimetry, and the results are summarized in Table 3. To determine the stoichiometry for the hTPO163–c-Mpl interaction, a soluble fragment of c-Mpl from residues 1–450 was titrated by hTPO163. The titration reaction exhibited two phases. The data were analyzed by assuming that the binding stoichiometry between hTPO163 and c-Mpl was 1:2. Two distinct association sites were found with the constants of 3.3 × 109 M–1 and 1.1 × 106 M–1, which appear to correspond to the expected high-affinity and low-affinity CRH-binding sites. It was concluded that hTPO163 interacts with soluble c-Mpl containing the extracellular CRH domains in a 1-to-2 manner with differing affinities [high affinity (nanomolar range) and low affinity (micromolar range)] to the same cytokine recognition surface of the CRH domain.

Table 3. Stoichiometry and association constants for the interaction of hTPO163 with the soluble region of c-Mpl.

| Titrant | Ligand | Stoichiometry | Ka, M-1* |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-Mpl | hTPO163 | 2:1 | 3.3 × 109/1.1 × 106 |

| c-Mpl | hTPO163 with TN1-Fab | 1:1 | 1.0 × 108 |

Association constant was determined by isothermal titration calorimetry. See text for details.

In a second set of experiments, hTPO163 (120 μM) was preincubated with the same amount of TN1-Fab and was used to titrate the soluble c-Mpl fragment. The binding stoichiometry in this experiment was 1:1, and only a single association constant of 1 × 108 M–1, corresponding to the high-affinity CRH association constant, was observed. This confirms the observation from the crystal structure that the binding of TN1 to hTPO163 occludes the low-affinity CRH-binding site. The fact that the association constant of hTPO163 and TN1 is ≈109 M–1, whereas that of c-Mpl at the low-affinity site is ≈106 M–1, explains the strong neutralizing activity of TN1-IgG.

Discussion

The TPO–TN1 interaction was exploited in crystallization of hTPO163 in complex with a Fab derived from TN1, and the Fab portion of the crystal allowed us to solve the structure from a single data set. The refined partial model including only the TN1-Fab provided enough phase information to reveal clear unbiased electron density for hTPO163. The tertiary structure of the hTPO163–TN1-Fab complex provided insight not only into the biological function of TPO but also into neutralizing activity of TN1 and the activation of c-Mpl.

Interpretation of Previous Mutagenic Experiments from the TPO-Fab Structure. Mutagenic experiments (42–45), along with sequence and structural comparison, allow further delineation of the structure–function relationships in TPO. EPO and TPO share 26 species of invariant residues as shown in Figs. 2 and 4. Of these, 13 species of invariant residues (L12, P42, W51, A60, L69, L70, L86, L104, L107, F128, L135, G137, and K138) are buried in the hydrophobic core of TPO, suggesting that they are important determinants of the structural frame. The invariant region consisting of L135, R136, G137, and K138 induces the distinct ≈20° bend in helix D of TPO, which is also observed in both the NMR and crystallographic structures of EPO, suggesting that this bend is another important aspect of the cytokine's structural frame.

Fig. 4.

Sequence alignment of TPO and EPO from various species. EPO-EPOR site 1 (▴) and site 2 (□) contacts are indicated as described by Syed et al. (22), except for R10 (▪), which contacts both EPOR monomers in the complex. Mutagenic data for TPO (42–45) and EPO (46, 54–56) are summarized in a general way with important (○) and critical (•) residues indicated. Secondary structures for TPO and EPO (41) are also indicated for reference.

Among the remaining residues, candidates for determinants of specificity for c-Mpl should include those residues that are invariant among known TPOs. Discounting residues that are buried in the hydrophobic core, the set of remaining candidates comprises 24 residues that fall into two distinct clusters corresponding to the proposed high- and low-affinity receptor interaction sites (blue and green in Fig. 5). The first cluster comprises 13 residues (V44, D45, F46, S47, L48, E50, A126, L129, Q132, H133, R140, F141, and L144). The second cluster comprises 11 residues (K14, R17, G91, Q92, S94, G95, L99, L101, G102, A103, and Q105). R10 is the only residue in EPO that interacts with both copies of the CRH domain in the 2:1 complex and is also a sequence invariant residue in TPO. The fact that the second cluster overlaps the recognition site of TN1-Fab and that the Fab binding to TPO did not affect the higher-affinity binding to CRH indicates that TN1-Fab only blocks the weaker receptor-binding site of TPO, resulting in prevention of the homodimerization of the TPO receptor.

Fig. 5.

Determinants of specificity of TPO for c-Mpl. Residues that are invariant within the TPO family but not conserved in the EPO family are proposed to confer specificity to the TPO–c-Mpl interaction. These residues fall into two distinct clusters corresponding to the proposed high-affinity (blue) and low-affinity (green) receptor interaction sites. Residues that are invariant in the TPO/EPO family are shown in black.

Implications for the Mechanism of Signal Transduction by c-Mpl. Sequential dimerization mechanisms, in which a 1:1 receptor–cytokine complex is formed initially by means of site 1 followed by binding of a second receptor by site 2, have been proposed for activation of both the EPOR (46) and hGHR (47, 48) based on biochemical and mutagenic data. However, this hypothesis seems to be overthrown, for EPOR at least, by crystallographic and biochemical evidence (49, 50) that unliganded EPOR predimerizes by its CRH domain in a signaling-incompetent conformation in which the intracellular domains of the receptor are held far enough apart to prevent autophosphorylation. Binding of EPO induces a reorientation of the receptor dimer to a signaling-competent conformation. This discovery raises interesting questions about the stoichiometry and manner of binding of TPO to the two CRH domains of c-Mpl.

The structural and titration calorimetric data presented here demonstrate that TPO possesses both low-affinity and high-affinity CRH-binding sites, as do EPO and hGH, and that the soluble extracellular region of c-Mpl containing the proximal and distal CRH domains forms a 2:1 complex with TPO. This is consistent with the current models for hematopoietic receptor activation. Recent studies demonstrate that the membrane-distal, but not the membrane-proximal, CRH domain of c-Mpl is a receptor domain for TPO. Binding of radioactively labeled TPO to BaF3 cells expressing mutants of murine c-Mpl was abolished when the distal CRH domain was either deleted or replaced with a second copy of the proximal CRH domain (51). These studies also showed that BaF3 cells expressing these c-Mpl mutants grew constitutively even in the absence of TPO, indicating that the membrane distal CRH domain also functions to inhibit autophosphorylation in the absence of TPO. The distal CRH domain therefore appears to fulfill both functions implied by the ligand-induced conformational change model of receptor activation (49, 50). The lack of any detectable interaction between hTPO and the proximal CRH domain leaves open the interesting possibility of another as-yet-unidentified cytokine ligand for c-Mpl, although experimental evidence to date strongly supports that TPO is the only c-Mpl ligand (52).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. N. Kamiya and M. Kawamoto of SPring-8 (proposal nos. 1999B0005-NL-np and 2000A0255-CL-np) and Drs. N. Sakabe, M. Suzuki, and N. Igarashi of the Photon Factory for data collection with synchrotron radiation. T. Tamada, H. Shigematsu, Y. Maeda, and R. Kuroki are members of the Structural Biology Sakabe Project of the Foundational Academy of International Science.

Abbreviations: TPO, thrombopoietin; CRH, cytokine receptor homology; hTPO, human TPO; EPO, erythropoietin; hGH, human growth hormone; EPOR, EPO receptor; hGHR, hGH receptor; NCS, noncrystallographic symmetry.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 1V7M and 1V7N).

References

- 1.Kelemen, E., Cserhati, I. & Tanos, B. (1958) Acta Haematol. 20, 350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartley, T. D., Bogenberger, J., Hunt, P., Li, Y. S., Lu, H. S., Martin, F., Chang, M. S., Samal, B., Nichol, J. L., Swift, S., et al. (1994) Cell 77, 1117–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Sauvage, F. J., Hass, P. E., Spencer, S. D., Malloy, B. E., Gurney, A. L., Spencer, S. A., Darbonne, W. C., Henzel, W. J., Wong, S. C., Kuang, W.-J., et al. (1994) Nature 369, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lok, S., Kaushansky, K., Holly, R. D., Kuijper, J. L., Lofton-Day, C. E., Oort, P. J., Grant, F. J., Heipel, M. D., Burkhead, S. K., Kramer, J. M., et al. (1994) Nature 369, 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato, T., Ogami, K., Shimada, Y., Iwamatsu, A., Sohma, Y., Akahori, H., Horie, K., Kokubo, A., Kudo, Y., Maeda, E., et al. (1995) J. Biochem. 118, 229–236, and correction (1995) 119, 208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuter, D. J. & Rosenberg, R. D. (1994) Blood 84, 1464–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wendling, F. (1999) Haematologica 84, 158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farese, A. M., Hunt, P., Boone, T. & MacVittie, T. J. (1995) Blood 86, 54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linden, H. & Kaushansky, K. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 3044–3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muto, T., Feese, M. D., Shimada, Y., Kudou, Y., Okamato, T., Ozawa, T., Tahara, T., Ohashi, H., Ogami, K., Kato, T., et al. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 12090–12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wendling, F., Vigon, I., Souyri, M. & Tambourin, P. (1989) Leukemia 3, 475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Souyri, M., Vigon, I., Penciolelli, J. F., Heard, J. M., Tambourin, P. & Wendling, F. (1990) Cell 63, 1137–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigon, I., Mornon, J. P., Cocault, L., Mitjavila, M. T., Tambourin, P., Gisselbrecht, S. & Souyri, M. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 5640–5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skoda, R. C., Seldin, D. C., Chiang, M. K., Peichel, C. L., Vogt, T. F. & Leder, P. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 2645–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solar, G. P., Kerr, W. G., Ziegler, F. C., Hess, D., Donahue, C., de Sauvage, F. J. & Eaton, D. (1998) Blood 92, 4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debili, N., Wendling, F., Cosman, D., Titeux, M., Florindo, C., Dusanter-Fourt, I., Schooley, K., Methia, N., Charon, M., Nador, R., et al. (1995) Blood 85, 391–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurney, A. L., Wong, S. C., Henzel, W. J. & de Sauvage, F. J. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5292–5296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyakawa, Y., Oda, A., Druker, B. J., Miyazaki, H., Handa, M. & Ikeda, Y. (1995) Blood 86, 23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sattler, M., Durstin, M. A., Frank, D. A., Okuda, K., Kaushansky, K., Salgia, R. & Griffin, J. D. (1995) Exp. Hematol. 23, 1040–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rouyez, M. C., Boucheron, C., Gisselbrecht, S., Dusanter-Fourt, I. & Porteu, F. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 4991–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumura, I., Nakajima, K., Wakao, H., Hattori, S., Hashimoto, K., Sugahara, H., Kato, T., Miyazaki, H., Hirano, T. & Kanakura, Y. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 4282–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Syed, R. S., Reid, S. W., Cuiwei, L., Cheetham, J. C., Aoki, K. H., Beishan, L., Zhang, H., Osslund, T. D., Chirino, A. J., Zhang, J., et al. (1998) Nature 395, 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vos, A. M., Ultsch, M. & Kossiakoff, A. A. (1992) Science 255, 306–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drachman, J. G. & Kaushansky, K. (1995) Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2, 22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mignotte, V., Vigon, I., Boucher de Crevecoeur, E., Romeo, P. H., Lemarchandel, V. & Chretien, S. (1994) Genomics 20, 5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohma, Y., Akahori, H., Seki, N., Hori, T. A., Ogami, K., Kato, T., Shimada, Y., Kawamura, K. & Miyazaki, H. (1994) FEBS Lett. 353, 57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuroki, R., Hirose, M., Kato, Y., Feese, M. D., Tamada, T., Shigematsu, H., Watarai, H., Maeda, Y., Tahara, T., Kato, T. & Miyazaki, H. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D 58, 856–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tahara, T., Kuwaki, T., Matsumoto, A., Morita, H., Watarai, H., Inagaki, Y., Ohashi, H., Ogami, K., Miyazaki, H. & Kato, T. (1998) Stem Cells 16, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navaza, J. (1994) Acta Crystallogr. A 50, 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernstein, F. C., Koetzle, T. F., Williams, G. J., Meyer, E. E., Jr., Brice, M. D., Rodgers, J. R., Kennard, O., Shimanouchi, T. & Tasumi, M. (1977) J. Mol. Biol. 112, 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews, B. W. (1985) Methods Enzymol. 114, 176–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ban, N., Escobar, C., Garcia, R., Hasel, K., Day, J., Greenwood, A. & McPherson, A. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tronrud, D. E., Ten Eyck, L. F. & Matthews, B. W. (1987) Acta Crystallogr. A 43, 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cowtan, K. D. & Main, P. (1996) Acta Crystallogr. D 52, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Read, R. J. (1986) Acta Crystallogr. A 42, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein, P. E., Boodhoo, A., Armstrong, G. D., Cockle, S. A., Klein, M. H. & Read, R. J. (1994) Structure 2, 45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murshudov, G. N., Vagin, A. A. & Dodson, E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D 53, 240–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wada, T., Nagata, Y., Nagahisa, H., Okutomi, K., Ha, S. H., Ohnuki, T., Kanaya, T., Matsumura, M. & Todokoro, K. (1995) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 213, 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kato, T., Oda, A., Inagaki, Y., Ohashi, H., Matsumoto, A., Ozaki, K., Miyakawa, Y., Watarai, H., Fuju, K., Kokubo, A., et al. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 4669–4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Foster, D. & Lok, S. (1996) Stem Cells 14, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheetham, J. C., Smith, D. M., Aoki, K. H., Stevenson, J. L., Hoeffel, T. J., Syed, R. S., Egrie, J. & Harvey, T. S. (1998) Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 861–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearce, K. H., Jr., Potts, B. J., Prestal, L. G., Bald, L. N., Fendly, B. M. & Wells, J. A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 20595–20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jagerschmidt, A., Fleury, V., Anger-Leroy, M., Thomas, C., Agnel, M. & O'Brien, D. P. (1998) Biochem. J. 333, 729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park, H., Park, S. S., Jin, E. H., Song, J.-S., Ryu, S.-E., Yu, M.-H. & Hong, H. J. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 256–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hou, J. & Zhan, H. (1998) Cytokine 10, 319–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthews, D. J., Topping, R. S., Cass, R. T. & Giebel, L. B. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9471–9474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cunningham, B. C., Ultsch, M., de Vos, A. M., Mulkerrin, M. G., Clauser, K. R. & Wells, J. A. (1991) Science 254, 821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fuh, G., Cunningham, B. C., Fukunaga, R., Nagata, S., Goeddel, D. V. & Wells, J. A. (1992) Science 256, 1677–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Remy, I., Wilson, I. A. & Michnick, S. W. (1999) Science 283, 990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Livnah, O., Stura, E. A., Middleton, S. A., Johnson, D. L., Jolliffe, L. K. & Wilson, I. A. (1999) Science 283, 987–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sabath, D. F., Kaushansky, K. & Broudy, V. C. (1999) Blood 94, 365–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander, W. S. (1999) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 31, 1027–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grodberg, J., Davis, K. L. & Sykowski, A. J. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 218, 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elliott, S., Lorenzini, T., Chang, D., Barzilay, J. & Delorme, E. (1997) Blood 89, 493–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wen, D., Boissel, J.-P., Showers, M., Ruch, B. C. & Bunn, H. F. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22839–22846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]