Abstract

Parkinson’s disease, the most common neurological disorder in the elderly, is characterized by progressive extrapyramidal motor dysfunction including resting tremors, muscle rigidity, hypolocomotion (bradykinesia and akinesia) and postural instability. Various non-motor features are also seen such as cognitive impairments (deficits in learning and memory) and mood disorders (depression and anxiety). While the 5-HT1A receptor has long been implicated in the pathogenesis and treatment of anxiety and depression, recent research has revealed new therapeutic roles for 5-HT1A receptors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. These include the modulation of parkinsonian motor symptoms, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA)-induced dyskinesia, cognitive impairments and emesis. Thus, 5-HT1A agonists improve the various motor disorders associated with dopaminergic deficits, dyskinesia induced by chronic L-DOPA treatment, mood disturbances (anxiety and depression) and dopamine agonist-induced emesis. In addition, partial 5-HT1A agonists are expected to improve cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s patients. These findings encourage research into new 5-HT1A receptor ligands, which will improve efficacy and/or ameliorate adverse reactions in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Keywords: 5-HT1A receptors, Parkinson’s disease, extrapyramidal motor disorders, cognitive impairment, depression, anxiety

Parkinson’s disease is a serious neurological disorder in the elderly and is estimated to affect about 1% of people older than 60 years. Patients with the disease show progressive extrapyramidal motor dysfunction including rest tremor, hypolocomotion (bradykinesia and akinesia), muscle rigidity and postural instability [1]. Resting tremor in Parkinson’s disease have a frequency of 3–5 Hz, affecting the hands, head and other parts of the body. Bradykinesia refers to reduced and impaired motor activity and manifests as the slowed and/or interrupted flow of voluntary movements. In advanced cases, patients exhibit freezing gait caused by a depletion of central norepinephrine, which can be improved by treatment with the norepinephrine precursor droxydopa (L-threo-dihydroxyphenylserine). Various non-motor features are also seen, including cognitive impairments (deficits in learning and memory), mood disorders (depression and anxiety), sleep disturbances and autonomic dysfunction (orthostatic hypotension and constipation) [1–3].

The serotonergic system plays crucial roles in controlling various physiological processes including psycho-emotional, sensori-motor, cognitive and autonomic functions [4–7]. 5-HT neurons are located in the raphe nuclei and send axons to various regions of the brain including the cerebral cortex, limbic areas, basal ganglia, diencephalon and spinal cord. Serotonergic neurotransmission is mediated by multiple 5-HT receptors consisting of at least 14 subtypes (i.e., 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT1D, 5-HT1E, 5-HT1F, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5a, 5-HT5b, 5-HT6 and 5-HT7 receptors), which can be classified into 7 families (5-HT1 to 5-HT7) [5–7]. These 5-HT receptors are mostly G-protein-coupled receptors with a 7-transmembrane spanning structure, except for the 5-HT3 receptor which functions as a ligand-gated cation (e.g. Na+ and Ca2+) channel [6].

Several lines of evidence have revealed that 5-HT1A receptors play an important role in controlling motor functions and ameliorate various extrapyramidal disorders such as parkinsonian motor symptoms [8–18] and L-DOPA-induced motor disabilities [19–22]. In addition, 5-HT1A receptors are implicated in the pathogenesis and treatment of mood disorders (e.g., anxiety and depression) [9, 10, 23–25] and cognitive impairments [7, 26–30], which are often seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease. These findings suggest that 5-HT1A receptors could serve as a promising therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease. In this article, we review the functional roles of 5-HT1A receptors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and illustrate therapeutic approaches by modulating 5-HT1A receptors.

Current medications for Parkinson’s disease

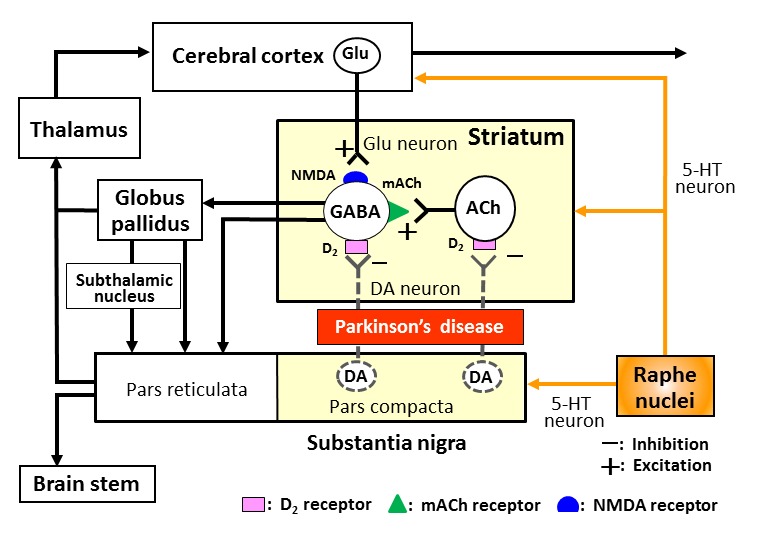

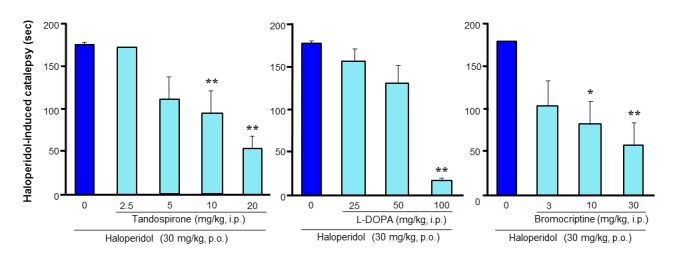

Extrapyramidal motor functions are mainly regulated by the basal ganglia including the striatum and globus pallidus, which from the basal ganglia-thalamus-cerebral cortex neural network (Fig. 1). It is known that striatal neurons receive glutamatergic excitatory inputs from the cerebral cortex and are also positively regulated by acetylcholinergic interneurons within the striatum. Dopaminergic neurons forms the substantia nigra negatively regulate both striatal output neurons and acetylcholinergic interneurons. Pathological findings have revealed that Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder, involving the selective loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 1). In patients with the disease, therefore, nigro-striatal dopaminergic activity is largely diminished and the activity of striatal acetylcholinergic neurons is elevated (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Neural network regulating extrapyramidal motor functions and Parkinson’s disease. Striatal GABAergic (GABA) output neurons receive glutamatergic (Glu) excitatory inputs from the cerebral cortex and excitatory inputs from acetylcholinergic (ACh) interneurons within the striatum. Dopaminergic (DA) neurons from the substantia nigra pars compacta negatively regulate both striatal output neurons and ACh interneurons. In patients with Parkinson’s disease, the nigro-striatal dopaminergic neurons are degenerated, which causes hyperexcitation of both GABA and ACh striatal neurons. The serotonergic (5-HT) neurons derived from the raphe nuclei project to the striatum, substantia nigra and cerebral cortex, and modulate the expression of extrapyramidal motor disorders.

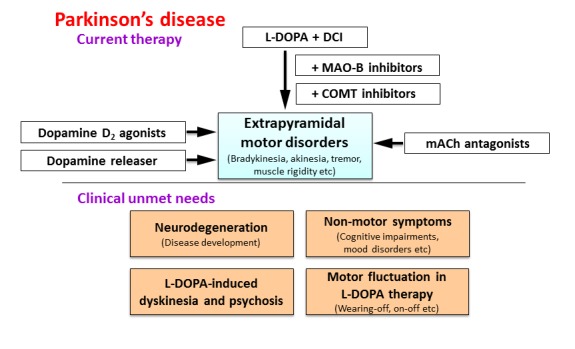

Patients with Parkinson’s disease are responsive to various dopaminergic drugs [1, 8]. The dopamine precursor L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA) has long been the most common drug for Parkinson’s disease since it effectively supplements brain dopamine and improves various parkinsonian symptoms (Fig. 2) [1]. Bromocriptine, pergolide, cabergoline, ropinirole and talipexole are D2 (D2/D3) agonists which directly stimulate these receptors, and amantadine acts as a dopamine releaser/NMDA antagonist (Fig. 2). Other drugs include the monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor selegiline and the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitor entacapone, which are useful as an adjunct medication with L-DOPA, potentiating its actions. In addition, antagonists for muscarinic acetylcholine (mACh) receptors (trihexyphenidyl and biperidene) are also effective against parkinsonian symptoms through they often cause serious adverse reactions (e.g., intestinal constipation, urinary retention, tachycardia and cognitive impairments) (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Clinical unmet needs in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Although dopaminergic agents are generally effective for various symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (see Current therapy), there are residual unmet needs (see Clinical unmet needs), including a lack of effectual medications for neurodegeneration, non-motor symptoms (e.g., mood disturbances and cognitive impairments) of Parkinson’s disease, motor complications (e.g., dyskinesia) or psychosis associated with chronic L-DOPA treatment and a fluctuation (e.g., wearing-off and onoff phenomena) in L-DOPA efficacy. DCI: Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase inhibitor, MAO-B: monoamine oxydase–B, COMT: catechol-O-methyltransferase, mACh: muscarinic acetylcholine.

Although dopaminergic medications are widely used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, there still exist clinical unmet needs, including a lack of drugs suitable for treating neurodegeneration, motor complications (dyskinesia) or psychosis associated with chronic L-DOPA treatment and non-motor symptoms (e.g., cognitive impairments and mood disorders) (Fig. 2) [8, 31]. Specifically, no drugs can prevent the disease’s development (i.e., neurodegeneration) or restore damaged dopaminergic neurons. In addition, under long-term treatment, the efficacy of L-DOPA fluctuates (e.g., wearing-off and on-off phenomena) and L-DOPA sometimes causes serious side effects (e.g., L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and psychosis) (Fig. 2) [1, 8, 19]. New medications effective not only for motor symptoms, but also for non-motor symptoms (e.g., cognitive impairments and mood disorders) are also required.

5-HT1A receptors and Parkinson’s disease

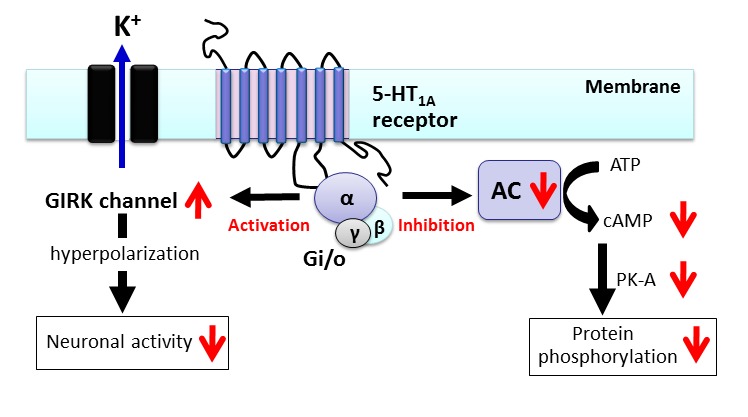

5-HT1A receptors are coupled to Gi/o protein, inhibit adenylate cyclase and c-AMP formation, and reduce protein kinase A (PK-A) activity (Fig. 3) [6–8, 32]. In addition, 5-HT1A receptors activate G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels, which facilitate the efflux of intracellular K+ and hyperpolarize target neurons. Thus, activation of 5-HT1A receptors inhibits the neural firing of target neurons (Fig. 3) [33–39].

Figure 3.

Signal transduction pathways of 5-HT1A receptors. The 5-HT1A receptor is a GPCR coupled to Gi/o protein. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors leads to inhibition of adenylate cyclase (AC) activity, cAMP formation and protein kinase A (PK-A)-mediated protein phosphorylation. 5-HT1A receptors also activate G-protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) channels and inhibit the activity of target neurons.

5-HT1A receptors are highly expressed in the limbic regions (hippocampus and amygdala), septum (lateral septal nucleus) and raphe nuclei (dorsal raphe nucleus and median raphe nucleus) [6, 32, 40, 41]. Besides these regions, 5-HT1A receptors are also expressed at moderate to low densities in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus and basal ganglia (e.g. striatum) [32, 40]. 5-HT1A receptors function both as pre-synaptic autoreceptors in the raphe nuclei and as post-synaptic receptors in other brain regions. 5-HT1A autoreceptors are located on somata and dendrites of 5-HT neurons in the raphe, where they negatively regulate 5-HT neuron activity [33]. Through this function, 5-HT1A autoreceptors can control the overall activity of the serotonergic system. On the other hand, post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors are located on membranes of neurons or nerve terminals (heteroreceptors) innervated by 5-HT neurons.

In Parkinson’s disease, loss of 5-HT neurons in the raphe nuclei has been reported [42]. Thus, 5-HT content and the density of 5-HT transporters (a marker for 5-HT nerve terminals) in the forebrain regions (e.g. striatum and neocortex) are reduced in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Alternatively, post-synaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors are up-regulated in response to the functional deficit of 5-HT neurons [42]. Furthermore, recent clinical study demonstrated that parkinsonian patients with depression show further pronounced dysfunction of 5-HT neurons as compared to the patients without depression [43]. Thus, there is a close relationship between dysfunction of the serotonergic system and Parkinson’s disease.

Roles of 5-HT1A receptors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease

1. Parkinsonian motor symptoms

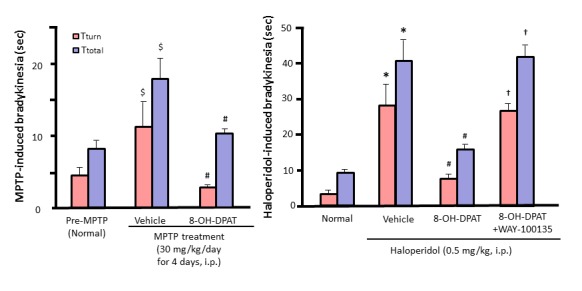

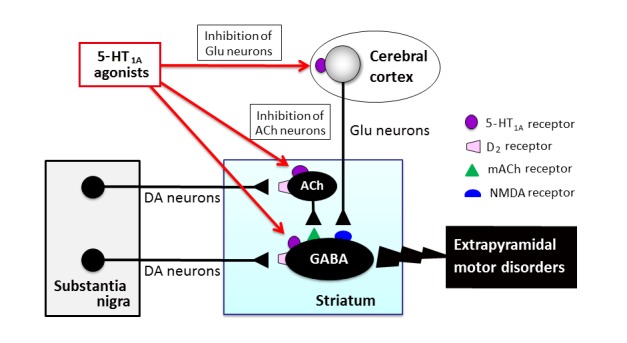

5-HT1A receptor stimulation ameliorates various extrapyramidal motor disorders [8–18]. A line of studies suggests that 5-HT1A agonists or partial agonists can ameliorate extrapyramidal disorders induced by the denervation of dopaminergic neurons or depletion of cerebral dopamine (Table. 1) [11, 12, 17, 44]. Namely, selective 5-HT1A agonists (e.g., 8-hydroxy-2-(di-npropylamino) tetralin (8-OH-DPAT)) ameliorate bradykinesia or hypolocomotion induced by dopaminergic neurotoxins (e.g., 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-pyridine (MPTP)) or akinesia induced by reserpine which depletes central monoamines (Fig. 4). Also, 5-HT1A agonists, like antiparkinsonian agents, produce contralateral rotation behavior in the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OH-DA)-hemilesioned rat model of Parkinson’s disease and ameliorate dyskinesia or hypolocomotion in MPTP-treated primate models (Table 1) [12, 13, 17, 45–50]. In addition, numerous studies have shown that activation of 5-HT1A receptors improves extrapyramidal disorders elicited by dopamine D2 antagonists (e.g., antipsychotics-induced parkinsonian symptoms). 5-HT1A full agonists (e.g., 8-OH-DPAT and flesinoxan) and 5-HT1A partial agonists (e.g., tandospirone and buspirone) attenuated D2 antagonist (e.g., haloperidol)-induced catalepsy, bradykinesia and other parkinsonian symptoms (Fig. 4, Fig 5 and Table. 1) [11–17, 51]. The improvement of extrapyramidal symptoms by 5-HT1A agonists is as potent as that by L-DOPA, the mACh receptor antagonist trihexyphenidyl or the D2 agonist bromocriptine, and is reversed by 5-HT1A antagonists (e.g., WAY-100135 and WAY-100635) (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5) [14, 15]. Furthermore, the ameliorative effect of 5-HT1A agonists is supported by the neurochemical findings that D2 antagonist-induced Fos expression in the striatum could be reversed by 5-HT1A agonists (e.g., 8-OH-DPAT and tandospirone), suggesting that stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors counteracts the D2 blocking actions of antipsychotics in striatum [15, 16].

Table 1.

Anti-parkinsonian and anti-dyskinetic actions of 5-HT1A agonists.

| Animal models | Drugs | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-parkinsonian actions | MPTP-induced bradykinesia and motor disturbance | 8-OH-DPAT, BAY-639044, repinotan, SLV308, sarizotan | [17, 45–47] |

| 6-OH-DA-induced rotation behavior | 8-OH-DPAT, tandospirone | [12, 13, 48] | |

| 6-OH-DA-induced catalepsy | Buspirone, 8-OH-DPAT | [49, 50] | |

| Reserpine-induced hypokinesia | 8-OH-DPAT, flesinoxan, buspirone, tandospirone | [12, 52, 53] | |

| D2 antagonist-induced catalepsy and bradykinesia | 8-OH-DPAT, tandospirone, buspirone, ipsapirone, eptapirone | [12, 14, 51] | |

| Anti-dyskinetic actions | L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia | 8-OH-DPAT, tandospirone, buspirone, sarizotan | [80, 82, 83] |

| D1 receptor-induced dyskinesia | 8-OH-DPAT | [44] |

Figure 4.

Ameliorative actions of the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT on MPTP- and D2 antagonist (i.e., haloperidol)-induced bradykinesia and its reversal by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100135 in mice. Tturn and Ttotal values are the time required for mice to rotate on the pole and to descent to the floor, respectively, in the mouse pole-test. Increases in Tturn and Ttotal values represent the induction of bradykinesia. $p<0.05 vs. Pre-MPTP (Normal). #p<0.05 vs. Vehicle + MPTP or Haloperidol. *p<0.05 vs. Normal. †p<0.05 vs. 8-OH-DPAT + Haloperidol.

Figure 5.

Ameliorative actions of the 5-HT1A agonist tandospirone and antiparkinsonian agents, L-DOPA and bromocriptine, on D2 antagonist (i.e., haloperidol)-induced catalepsy in rats. The 5-HT1A agonist tandospirone ameliorated catalepsy with a similar potency to L-DOPA and greater potency than the D2 agonist bromocriptine. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. Haloperidol alone.

The fact that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors ameliorates the motor dysfunction caused by damage to dopaminergic neurons [12, 13, 17, 45] implies that 5-HT1A agonists alleviate extrapyramidal symptoms through non-dopaminergic mechanisms. Moreover, the ameliorative effect of 5-HT1A agonists on akinesia in reserpine-treated rats was reversed by the 5-HT1A antagonist WAY-100135, but not by the D2 antagonist haloperidol [12, 52, 53]. It is therefore likely that 5-HT1A agonists produce antiparkinsonian actions in an additive fashion with currently used dopaminergic agents (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Post-synaptic mechanisms underlying the antiparkinsonian actions of 5-HT1A agonists. 5-HT1A agonists ameliorated extrapyramidal motor disfunction through post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors even in animals with denervated serotonergic neurons. In addition, the local microinjection of 5-HT1A agonists into the striatum or the cerebral cortex (motor cortex) exerted antiparkinsonian actions. DA: dopamine, ACh: acetylcholine, Glu: glutamate.

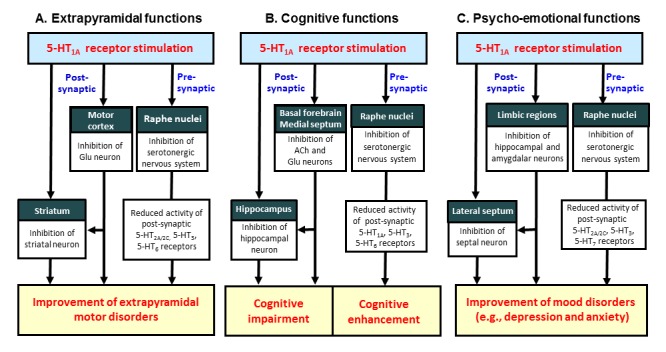

5-HT1A agonists alleviate extrapyramidal symptoms even in animals in which pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors were inactivated by the tryptophan hydroxylase inhibitor, p-chlorophenylalanine (PCPA). Therefore 5-HT1A agonists seem to exert antiparkinsonian actions at least partly by activating post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7) [14]. In addition, bilateral microinjections of 8-OH-DPAT into the cerebral cortex or striatum significantly attenuated D2 antagonist-induced catalepsy in rats [17]. Thus, it is likely that the ameliorative action of 5-HT1A agonists is mediated by post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors in the cerebral cortex and striatum, probably by inhibiting the neuronal activity in these regions (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). As the activities of striatal neurons are positively regulated by glutamatergic neurons derived from the motor cortex [8], and since NMDA antagonists reduce the neural activity of striatal neurons as well as extrapyramidal motor disorders [54–57], activation of 5-HT1A receptors in the motor cortex seems to exert ameliorative actions by inhibiting the corticostriatal glutamatergic neurons (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). On the other hand, previous studies showed that the microinjection of 8-OH-DPAT into the raphe nuclei also alleviated haloperidol-induced catalepsy [58–60]. Therefore, it is also possible that the activation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors inhibits serotonergic neuron activities, which consequently reduces the activity of post-synaptic 5-HT2A/2C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors and alleviates extrapyramidal motor symptoms (Fig. 7) [61, 62].

Figure 7.

Mechanisms of action of 5-HT1A agonists in modulating extrapyramidal, cognitive and psycho-emotional functions. A: Stimulation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors reduces the activity of striatal neurons directly by hyperpolarizing striatal neurons and indirectly by inhibiting Glu neurons in the motor cortex. In addition, stimulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors inhibits serotonergic neuronal activities, thereby reducing the functions of 5-HT2A/2C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors. B: Stimulation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors inhibits cognitive functions by reducing the activity of cholinergic and/or glutamatergic neurons in the basal forebrain and medial septum, and by inhibiting ACh release in the hippocampus. By contrast, stimulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors enhances cognitive functions by reducing serotonergic neuron activities (e.g., inhibition of 5-HT1A, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors which impair cognitive functions). C: 5-HT1A receptors are highly expressed in the limbic areas (e.g., hippocampus and amygdala) and lateral septum, which are involved in generation of depression and anxiety. Stimulation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors exert anxiolytic and/or antidepressant effects by inhibiting the activity of the limbic neurons (i.e., hippocampus and amygdala) and the lateral septal neurons. In addition, activation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors reduce the activity of 5-HT2A/2C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT7 receptors which are implicated in generation of mood disorders.

2. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease accompanies diverse non-motor symptoms including cognitive impairments, psycho-emotional changes (e.g., anxiety and depression), sleep disturbances and autonomic dysfunction (Fig. 2) [1–3, 9, 63]. Among these, cognitive impairments develop in about 40% of patients and most patients (more than 80%) have dementia at the end-stage of the disease [3]. Moreover, anxiety and depression are very common, affecting about 50% of individuals with Parkinson’s disease [63]. Thus, besides the treatment of core motor symptoms, control of non-motor symptoms, especially psycho-emotional disturbances and cognitive impairments, is key to improving the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease [1].

2.1. Cognitive impairments

5-HT1A receptors play an important role in modulating cognitive functions (e.g., learning and memory) [27, 30, 64–66]. It has been reported that 8-OH-DPAT exhibits biphasic effects, in that high doses impair and low doses enhance cognitive functions [27, 30]. These inhibitory and stimulatory actions seem to be mediated by activation of post-synaptic and pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, respectively (Fig. 7). Namely, cognitive impairment by the stimulation of post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors probably occurs through 1) inhibition of the activity of acetylcholinergic and/or glutamatergic neurons projecting to the cerebral cortex or hippocampus in the basal forebrain (e.g., diagonal band of Broca and medial septum), 2) inhibition of the activity of the hippocampal and cortical neurons, receiving the above acetylcholinergic or glutamatergic inputs, and 3) a reduction in the release of ACh within the hippocampus (Fig. 7). On the other hand, stimulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors inhibits the activity of 5-HT neurons, thereby reducing the activity of post-synaptic 5-HT1A, 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors which impair cognitive functions [7]. Indeed, it is reported that 5-HT1A antagonists (e.g., WAY-100635, WAY-101405, NAD-299 and lecozotan) and partial 5-HT1A agonists (e.g., tandospirone) improve the cognitive impairments induced by mACh receptor antagonists (e.g., scopolamine) or N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists (e.g., MK-801) [27, 30, 64–66].28,31,89–91 Thus, 5-HT1A antagonists or partial agonists are expected to improve the cognitive deficits in Parkinson’s disease. However, this is not conclusive since several studies reported that 5-HT1A agonists improve cognitive impairments in Parkinson’s disease [18, 67].

2.2. Mood disorders

It is well known that 5-HT1A receptors are involved in the pathogenesis and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. 5-HT1A full agonists and partial agonists produce anti-anxiety effects in various animal models (e.g., Vogel’s conflict, elevated-plus maze, social interaction and conditioned-fear freezing tests) [10, 25, 68–71]. These anxiolytic actions of 5-HT1A agonists (e.g., 8-OH-DPAT, buspirone and tandospirone) are reversed by selective 5-HT1A antagonists (e.g., WAY-100635 and WAY-100135) [69, 70]. In addition, knockout mice lacking 5-HT1A receptors exhibit signs of advanced anxiety [72–74]. Conversely, transgenic mice overexpressing 5-HT1A receptors show reduced anxiety behavior [41]. Moreover, 5-HT1A agonists significantly improve depressive behavior (e.g., increase in immobility time in the forced swim test) following repeated administrations [75–78].

It is likely that the anxiolytic and antidepressant actions of 5-HT1A agonists are mediated by both post-synaptic and pre-synaptic receptors (Fig. 7). 5-HT1A receptors are mainly located in the limbic regions (hippocampus and amygdala) and lateral septum, which are implicated in the generation of mood disorders. It is suggested that 5-HT1A agonists produce anxiolytic and antidepressant effects by inhibiting the neural activity of limbic neurons and lateral septal neurons via 5-HT1A-activated GIRK channels (Fig. 3) [8, 10, 33–39, 69–79]. On the other hand, activation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A autoreceptors in the raphe nuclei inhibit the activity of 5-HT2A/2C, 5-HT3 and 5-HT7 receptors, which are implicated in the generation of depression and/or anxiety (Fig. 7).

3. Drug-related adverse reactions

3.1. L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia

For more than 40 years, dopamine replacement therapy using L-DOPA has been the mainstay of treatments for Parkinson’s disease [1, 8, 19, 31]. However, L-DOPA often has fluctuations in its efficacy (e.g., wearing-off and on-off phenomena) and/or serious side effects (e.g., dyskinesia and psychosis) after long-term treatment (Fig. 2) [8, 19, 31]. L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia manifests as dystonic, choreic and athetotic movements, which affect the limbs, hands, trunk and lingual-facial-buccal muscular systems at various points of the L-DOPA cycle. The prevalence of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia during the treatment is reported at 30–80% [31]. Risk factors for L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia include an earlier onset of Parkinson’s disease, longer duration of the disease, longer duration of L-DOPA therapy, total L-DOPA exposure and female gender. As L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia is generally difficult to treat and often hampers continued treatment, there is a great clinical need to modulate it (Fig. 2) [1, 8, 19, 31].

Although the precise mechanisms underlying the dyskinesia are still unknown, activation of the D1 receptor and/or an imbalance of D1-D2 receptor functions are thought to be important in the generation of dyskinesia [19, 31]. Indeed, stimulation of D1 receptors by D1 agonists (e.g., SKF-81297) induces abnormal involuntary movements (vacuous chewing, tongue extrusion, repetitive jaw movements etc) in several animal models [44]. Furthermore, various neurotransmitter systems including the serotonergic, noradrenergic and glutamatergic systems are also suggested to be involved in the development of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia [31].

It has been reported that 5-HT1A receptor agonists inhibit dyskinesia in animals chronically treated with L-DOPA (Table 1) [20–22]. Previous studies also showed that 5-HT1A agonists (e.g., 8-OH-DPAT and tandospirone) improved dyskinesia in MPTP-treated primates without affecting the antiparkinsonian action of L-DOPA [80–85]. Microinjection studies revealed that activation of 5-HT1A receptors in the striatum and motor cortex by 8-OH-DPAT alleviated L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia [22, 44, 83, 86], indicating that the anti-dyskinetic actions of 5-HT1A agonists are mediated at least partly by post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors in both the striatum and motor cortex. Furthermore, microdialysis studies showed that the actions of 5-HT1A agonists in the cerebral cortex (primary motor areas) reduce glutamate release in the striatum, which contributes to inhibition of the induction of dyskinesia [56, 87]. Thus, the activation by 5-HT1A receptors agonists is conceivably a favorable treatment approach for L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease.

3.2. Dopamine agonist-induced emesis

Dopaminomimetic agents for Parkinson’s disease including L-DOPA and D2 agonists (bromocriptine, pergolide, cabergoline, ropinirole and talipexole) induce nausea and emesis. It is known that 5-HT1A receptors modulate neural control of nausea and emesis. Studies have shown that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors by 5-HT1A agonists inhibits apomorphine (D2 agonist)-induced emesis in various animal models (e.g., pigeons, cats and house shrews) [88]. It is therefore likely that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors is a useful approach to preventing dopamine agonist-induced nausea and emesis in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Conclusion

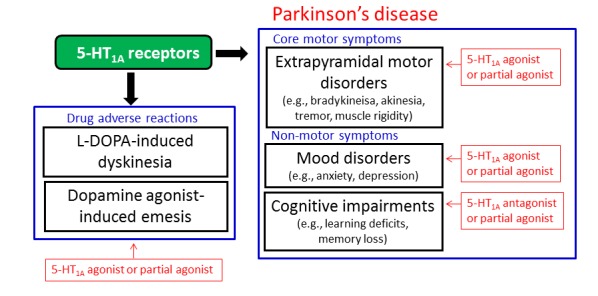

In this article, we reviewed the therapeutic roles of 5-HT1A receptors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. It is now evident that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors ameliorates parkinsonian motor symptoms in various animal models (e.g., MPTP-induced bradykinesia and motor disabilities, 6-OH-DA-induced catalepsy, contralateral rotation behavior in the 6-OH-DA-hemilesioned model, D2 antagonist-induced bradykinesia and catalepsy). The efficacy of 5-HT1A agonists in improving parkinsonian motor symptoms seems to be as good as that of currently used antiparkinsonian agents (e.g., L-DOPA, D2 agonists and mACh antagonists). In addition, since the antiparkinsonian actions of 5-HT1A agonists occur through non-dopaminergic mechanisms, 5-HT1A agonists seem to exert antiparkinsonian actions in an additive fashion with currently used dopaminergic agents (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

5-HT1A receptors as a therapeutic target in Parkinson’s disease. 5-HT1A receptors seem to be a favorable target for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. 5-HT1A agonists or 5-HT1A partial agonists are expected to be effective for L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia, mood disorders and dopamine agonist-induced emesis as well as parkinsonian core motor symptoms. 5-HT1A partial agonists or 5-HT1A antagonists may also be useful for treating the cognitive impairments associated with Parkinson’s disease.

It is well documented that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors is involved in the treatment of depression and anxiety, which are often seen in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Although further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms involved and clinical efficacy, partial 5-HT1A agonists or 5-HT1A antagonists are expected to ameliorate cognitive impairments in Parkinson’s disease. It is therefore likely that 5-HT1A receptors are an attractive target for treating non-motor symptoms (i.e., cognitive impairments and mood disorders) of Parkinson’s disease (Fig. 8). Finally, 5-HT1A agonists seem to alleviate drug-related adverse reactions such as L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and dopamine agonist-induced emesis. Notably, 5-HT1A agonists exert clear efficacy against dyskinesia, one of the main side effects of L-DOPA (Fig. 8).

The present review illustrates that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors provides multiple benefits in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease, i.e., amelioration of the core parkinsonian symptoms, cognitive impairments, mood disorders, L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and dopamine agonist-induced emesis (Fig. 8). These findings encourage the synthesis of new 5-HT1A agonists with favorable 5-HT1A selectivity and pharmacodynamic properties. In addition, designing compounds which possess combined activities for both 5-HT1A and dopamine D2 receptors seems to be a promising approach to the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. These new ligands for 5-HT1A receptors may overcome limitations of clinical efficacy and/or improve adverse reactions in the current treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

References

- [1].Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 2004;363:1783–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16305-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gallagher DA, Schrag A. Psychosis, apathy, depression and anxiety in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2012;46:581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meireles J, Massano J. Cognitive impairment and dementia in Parkinson’s disease: clinical features, diagnosis, and management. Front Neurol. 2012;3:88. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Roth BL. Multiple serotonin receptors: Clinical and experimental aspects. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;6:67–78. doi: 10.3109/10401239409148985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Baumgarten HG, Grozdanovic Z. Psychopharmacology of central serotonergic systems. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1995;2:73–79. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barnes NM, Sharp T. A review of central 5-HT receptors and their function. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1083–1152. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ohno Y, Tatara A, Shimizu S, Sasa M. Management of cognitive impairments in schizophrenia: the therapeutic role of 5-HT receptors. In: Sumiyoshi T, editor. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2012. pp. 321–335. Schizophrenia Research: Recent Advances., [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ohno Y. Therapeutic role of 5-HT1A receptors in the treatment of schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17:58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ohno Y. Tandospirone citrate, a new serotonergic anxiolytic agent: A potential use in Parkinson’s disease. In: Mizuno Y, Fisher A, Hanin A, editors. Mapping the progress of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2002. pp. 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ohno Y. New insight into the therapeutic role of 5-HT1A receptors in central nervous system disorders. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2010;10:148–157. doi: 10.2174/187152410791196341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mignon L, Wolf WA. Postsynaptic 5-HT(1A) receptors mediate an increase in locomotor activity in the monoamine-depleted rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;163:85–94. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ishibashi T, Ohno Y. Antiparkinsonian actions of a selective 5-HT1A agonist, tandospirone, in rats. Biog Amines. 2004;8:329–338. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Matsubara K, Shimizu K, Suno M, Ogawa K, Awaya T, Yamada T, Noda T, Satomi M, Ohtaki K, Chiba K, Tasaki Y, Shiono H. Tandospirone, a 5-HT1A agonist, ameliorates movement disorder via nondopaminergic systems in rats with unilateral 6-hydroxydopamine-generated lesions. Brain Res. 2008;1112:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ohno Y, Shimizu S, Imaki J, Ishihara S, Sofue N, Sasa M, Kawai Y. Evaluation of the antibradykinetic actions of 5-HT1A agonists using the mouse pole test. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1302–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ohno Y, Shimizu S, Imaki J, Ishihara S, Sofue N, Sasa M, Kawai Y. Anticataleptic 8-OH-DPAT preferentially counteracts with haloperidol-induced Fos expression in the dorsolateral striatum and the core region of the nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ohno Y, Shimizu S, Imaki J. Effects of tandospirone, a 5-HT1A agonistic anxiolytic agent, on haloperidol-induced catalepsy and forebrain Fos expression in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:593–599. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08313fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shimizu S, Tatara A, Imaki J, Ohno Y. Role of cortical and striatal 5-HT1A receptors in alleviating antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:877–881. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Newman-Tancredi A. The importance of 5-HT1A receptor agonism in antipsychotic drug action: rationale and perspectives. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:802–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cheshire PA, Williams DR. Serotonergic involvement in levodopa-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tomiyama M, Kimura T, Maeda T, Kannari K, Matsunaga M, Baba M. A serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist prevents behavioral sensitization to L-DOPA in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Res. 2005;52:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Dupre KB, Eskow KL, Steiniger A, Klioueva A, Negron GE, Lormand L, Park JY, Bishop C. Effects of coincident 5-HT1A receptor stimulation and NMDA receptor antagonism on L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia and rotational behaviors in the hemi-parkinsonian rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:99–108. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bishop C, Krolewski DM, Eskow KL, Barnum CJ, Dupre KB, Deak T, Walker PD. Contribution of the striatum to the effects of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation in L-DOPA-treated hemiparkinsonian rats. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:1645–1658. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Feighner JP, Boyer WF. Serotonin-1A anxiolytics: an overview. Psychopathology. 1989;22:21–26. doi: 10.1159/000284623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fuller RW. Role of serotonin in therapy of depression and related disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1991;52:52–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Akimova E, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S. The serotonin-1A receptor in anxiety disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Misane I, Ogren SO. Selective 5-HT1A antagonists WAY 100635 and NAD-299 attenuate the impairment of passive avoidance caused by scopolamine in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:253–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lüttgen M, Elvander E, Madjid N, Ogren SO. Analysis of the role of 5-HT1A receptors in spatial and aversive learning in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:830–852. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Madjid N, Tottie EE, Lüttgen M, Meister B, Sandin J, Kuzmin A, Stiedl O, Ogren SO. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor blockade facilitates aversive learning in mice: interactions with cholinergic and glutamatergic mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:581–591. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ogren SO, Eriksson TM, Elvander-Tottie E, D’Addario C, Ekström JC, Svenningsson P, Meister B, Kehr J, Stiedl O. The role of 5-HT(1A) receptors in learning and memory. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:54–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].King MV, Marsden CA, Fone KC. A role for the 5-HT(1A), 5-HT4 and 5-HT6 receptors in learning and memory. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:482–492. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fabbrini G, Brotchie JM, Grandas F, Nomoto M, Goetz CG. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1379–1389. doi: 10.1002/mds.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pucadyil TJ, Kalipatnapu S, Chattopadhyay A. The serotonin1A receptor: a representative member of the serotonin receptor family. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2005;25:553–580. doi: 10.1007/s10571-005-3969-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Blier P, Ward NM. Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression? Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hirose A, Sasa M, Akaike A, Takaori S. Inhibition of hippocampal CA1 neurons by 5-hydroxytryptamine, derived from the dorsal raphe nucleus and the 5-hydroxytryptamine1A agonist SM-3997. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:93–101. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90048-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Van den Hooff P, Galvan M. Actions of 5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-HT1A receptor ligands on rat dorso-lateral septal neurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:893–899. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hadrava V, Blier P, Dennis T, Ortemann C, de Montigny C. Characterization of 5-hydroxytryptamine1A properties of flesinoxan: in vivo electrophysiology and hypothermia study. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:1311–1326. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00098-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ohno Y, Ishida K, Ishibashi T, Tanaka H, Shimizu H, Nakamura M. Effects of tandospirone, a selective 5-HT1A agonist, on activities of the lateral septal nucleus neurons in cats. In: Takada Y, Curzon G, editors. Serotonin in the Central Nervous System and Periphery. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Science. BV; 1995. pp. 159–165. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Raymond JR, Mukhin YV, Gettys TW, Garnovskaya MN. The recombinant 5-HT1A receptor: G protein coupling and signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1751–1764. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Tada K, Kasamo K, Ueda N, Suzuki T, Kojima T, Ishikawa K. Anxiolytic 5-hydroxytryptamine1A agonists suppress firing activity of dorsal hippocampus CA1 pyramidal neurons through a postsynaptic mechanism: single-unit study in unanesthetized, unrestrained rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Luna-Munguía H, Manuel-Apolinar L, Rocha L, Meneses A. 5-HT1A receptor expression during memory formation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:309–318. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Kusserow H, Davies B, Hörtnagl H, Voigt I, Stroh T, Bert B, Deng DR, Fink H, Veh RW, Theuring F. Reduced anxiety-related behaviour in transgenic mice overexpressing serotonin 1A receptors. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;129:104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen CP, Alder JT, Bray L, Kingsbury AE, Francis PT, Foster OJ. Post-synaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors are increased in Parkinson’s disease neocortex. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;861:288–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Huot P, Johnston TH, Visanji NP, Darr T, Pires D, Hazrati LN, Brotchie JM, Fox SH. Increased levels of 5-HT1A receptor binding in ventral visual pathways in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2012;27:735–742. doi: 10.1002/mds.24964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dupre KB, Eskow KL, Barnum CJ, Bishop C. Striatal 5-HT1A receptor stimulation reduces D1 receptor-induced dyskinesia and improves movement in the hemiparkinsonian rat. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1321–1328. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jones CA, Johnston LC, Jackson MJ, Smith LA, van Scharrenburg G, Rose S, Jenner PG, McCreary AC. An in vivo pharmacological evaluation of pardoprunox (SLV308)--a novel combined dopamine D(2)/D(3) receptor partial agonist and 5-HT(1A) receptor agonist with efficacy in experimental models of Parkinson’s disease. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20:582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bezard E, Gerlach I, Moratalla R, Gross CE, Jork R. 5-HT1A receptor agonist-mediated protection from MPTP toxicity in mouse and macaque models of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bibbiani F, Oh JD, Chase TN. Serotonin 5-HT1A agonist improves motor complications in rodent and primate parkinsonian models. Neurology. 2001;57:1829–1834. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Gerber R, Altar CA, Liebman JM. Rotational behavior induced by 8-hydroxy-DPAT, a putative 5-HT1A agonist, in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1988;94:178–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00176841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nayebi AM, Rad SR, Saberian M, Azimzadeh S, Samini M. Buspirone improves 6-hydroxydopamine-induced catalepsy through stimulation of nigral 5-HT(1A) receptors in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2010;62:258–264. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(10)70264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mahmoudi J, Mohajjel Nayebi A, Samini M, Reyhani-Rad S, Babapour V. 5-HT(1A) receptor activation improves anti-cataleptic effects of levodopa in 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Daru. 2011;19:338–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Prinssen EP, Colpaert FC, Koek W. 5-HT1A receptor activation and anti-cataleptic effects: high-efficacy agonists maximally inhibit haloperidol-induced catalepsy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;453:217–221. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Ahlenius S, Hillegaart V, Salmi P, Wijkström A. Effects of 5-HT1A receptor agonists on patterns of rat motor activity in relation to effects on forebrain monoamine synthesis. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;72:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ahlenius S, Salmi P. Antagonism of reserpine-induced suppression of spontaneous motor activity by stimulation of 5-HT1A receptors in rats. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;76:149–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1995.tb00122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Chartoff EH, Ward RP, Dorsa DM. Role of adenosine and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in mediating haloperidol-induced gene expression and catalepsy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Steece-Collier K, Chambers LK, Jaw-Tsai SS, Menniti FS, Greenamyre JT. Antiparkinsonian actions of CP-101,606, an antagonist of NR2B subunit-containing N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors. Exp Neurol. 2000;163:239–243. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hussain N, Flumerfelt BA, Rajakumar N. Glutamatergic regulation of haloperidol-induced c-fos expression in the rat striatum and nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2001;102:391–399. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Yanahashi S, Hashimoto K, Hattori K, Yuasa S, Iyo M. Role of NMDA receptor subtypes in the induction of catalepsy and increase in Fos protein expression after administration of haloperidol. Brain Res. 2004;1011:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Invernizzi RW, Cervo L, Samanin R. 8-Hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino) tetralin, a selective serotonin1A receptor agonist, blocks haloperidol-induced catalepsy by an action on raphe nuclei medianus and dorsalis. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wadenberg ML, Hillegaart V. Stimulation of median, but not dorsal, raphe 5-HT1A autoreceptors by the local application of 8-OH-DPAT reverses raclopride-induced catalepsy in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34:495–499. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00013-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wadenberg ML, Young KA, Richter JT, Hicks PB. Effects of local application of 5-hydroxytryptamine into the dorsal or median raphe nuclei on haloperidol-induced catalepsy in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:151–156. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(98)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ohno Y, Imaki J, Mae Y, Takahashi T, Tatara A. Serotonergic modulation of extrapyramidal motor disorders in mice and rats: role of striatal 5-HT3 and 5-HT6 receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tatara A, Shimizu S, Shin N, Sato M, Sugiuchi T, Imaki J, Ohno Y. Modulation of antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal side effects by medications for mood disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;38:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Richard IH, Schiffer RB, Kurlan R. Anxiety and Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1996;8:383–392. doi: 10.1176/jnp.8.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Misane I, Ogren SO. Selective 5-HT1A antagonists WAY 100635 and NAD-299 attenuate the impairment of passive avoidance caused by scopolamine in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:253–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Madjid N, Tottie EE, Lüttgen M, Meister B, Sandin J, Kuzmin A, Stiedl O, Ogren SO. 5-Hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor blockade facilitates aversive learning in mice: interactions with cholinergic and glutamatergic mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:581–591. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.092262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Ogren SO, Eriksson TM, Elvander-Tottie E, D’Addario C, Ekström JC, Svenningsson P, Meister B, Kehr J, Stiedl O. The role of 5-HT(1A) receptors in learning and memory. Behav Brain Res. 2008;195:54–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Depoortère R, Auclair AL, Bardin L, Colpaert FC, Vacher B, Newman-Tancredi A. F15599, a preferential post-synaptic 5-HT1A receptor agonist: activity in models of cognition in comparison with reference 5-HT1A receptor agonists. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20:641–654. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Feighner JP, Boyer WF. Serotonin-1A anxiolytics: an overview. Psychopathology. 1989;22:21–26. doi: 10.1159/000284623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kataoka Y, Shibata K, Miyazaki A, Inoue Y, Tominaga K, Koizumi S, Ueki S, Niwa M. Involvement of the dorsal hippocampus in mediation of the antianxiety action of tandospirone, a 5-hydroxytryptamine1A agonistic anxiolytic. Neuropharmacology. 1991;30:475–480. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(91)90009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Shimizu H, Tatsuno T, Tanaka H, Hirose A, Araki Y, Nakamura M. Serotonergic mechanisms in anxiolytic effect of tandospirone in the Vogel conflict test. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1992;59:105–112. doi: 10.1254/jjp.59.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Stefański R, Pałejko W, Kostowski W, PłaŸnik A. The comparison of benzodiazepine derivatives and serotonergic agonists and antagonists in two animal models of anxiety. Neuropharmacology. 1992;31:1251–1258. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(92)90053-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Parks CL, Robinson PS, Sibille E, Shenk T, Toth M. Increased anxiety of mice lacking the serotonin1A receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10734–10739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ramboz S, Oosting R, Amara DA, Kung HF, Blier P, Mendelsohn M, Mann JJ, Brunner D, Hen R. Serotonin receptor 1A knockout: an animal model of anxiety-related disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14476–14481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Klemenhagen KC, Gordon JA, David DJ, Hen R, Gross CT. Increased fear response to contextual cues in mice lacking the 5-HT1A receptor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:101–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wieland S, Lucki I. Antidepressant-like activity of 5-HT1A agonists measured with the forced swim test. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1990;101:497–504. doi: 10.1007/BF02244228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Schreiber R, Brocco M, Gobert A, Veiga S, Millan MJ. The potent activity of the 5-HT1A receptor agonists, S 14506 and S 14671, in the rat forced swim test is blocked by novel 5-HT1A receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;271:537–541. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90816-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Matsuda T, Somboonthum P, Suzuki M, Asano S, Baba A. Antidepressant-like effect by postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptor activation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280:235–238. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00254-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Koek W, Vacher B, Cosi C, Assié MB, Patoiseau JF, Pauwels PJ, Colpaert FC. 5-HT1A receptor activation and antidepressant-like effects: F 13714 has high efficacy and marked antidepressant potential. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;420:103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Gross C, Zhuang X, Stark K, Ramboz S, Oosting R, Kirby L, Santarelli L, Beck S, Hen R. Serotonin1A receptor acts during development to establish normal anxiety-like behaviour in the adult. Nature. 2002;416:396–400. doi: 10.1038/416396a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Elliott PJ, Walsh DM, Close SP, Higgins GA, Hayes AG. Behavioural effects of serotonin agonists and antagonists in the rat and marmoset. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:949–956. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90146-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bibbiani F, Oh JD, Chase TN. Serotonin 5-HT1A agonist improves motor complications in rodent and primate parkinsonian models. Neurology. 2001;57:1829–1834. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Muñoz A, Li Q, Gardoni F, Marcello E, Qin C, Carlsson T, Kirik D, Di Luca M, Björklund A, Bezard E, Carta M. Combined 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptor agonists for the treatment of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Brain. 2008;131:3380–3394. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Ostock CY, Dupre KB, Jaunarajs KL, Walters H, George J, Krolewski D, Walker PD, Bishop C. Role of the primary motor cortex in L-Dopa-induced dyskinesia and its modulation by 5-HT1A receptor stimulation. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Eskow KL, Gupta V, Alam S, Park JY, Bishop C. The partial 5-HT(1A) agonist buspirone reduces the expression and development of l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia in rats and improves l-DOPA efficacy. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;87:306–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Grégoire L, Samadi P, Graham J, Bédard PJ, Bartoszyk GD, Di Paolo T. Low doses of sarizotan reduce dyskinesias and maintain antiparkinsonian efficacy of L-Dopa in parkinsonian monkeys. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:445–452. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Huot P, Johnston TH, Koprich JB, Winkelmolen L, Fox SH, Brotchie JM. Regulation of cortical and striatal 5-HT1A receptors in the MPTP-lesioned macaque. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Antonelli T, Fuxe K, Tomasini MC, Bartoszyk GD, Seyfried CA, Tanganelli S, Ferraro L. Effects of sarizotan on the corticostriatal glutamate pathways. Synapse. 2005;58:193–199. doi: 10.1002/syn.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Depoortère R, Barret-Grévoz C, Bardin L, Newman-Tancredi A. Apomorphine-induced emesis in dogs: differential sensitivity to established and novel dopamine D2/5-HT(1A) antipsychotic compounds. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;597:34–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]