Abstract

Lack of adherence, inaccessibility to viral reservoirs, long-term drug toxicities, and treatment failures are limitations of current antiretroviral therapy (ART). These limitations lead to increased viral loads, medicine resistance, immunocompromise, and comorbid conditions. To this end, we developed long-acting nanoformulated ART (nanoART) through modifications of existing atazanavir, ritonavir, and efavirenz suspensions in order to establish cell and tissue drug depots to achieve sustained antiretroviral responses. NanoART's abilities to affect immune and antiviral responses, before or following human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection were tested in nonobese severe combined immune-deficient mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Weekly subcutaneous injections of drug nanoformulations at doses from 80 mg/kg to 250 mg/kg, 1 day before and/or 1 and 7 days after viral exposure, elicited drug levels that paralleled the human median effective concentration, and with limited toxicities. NanoART treatment attenuated viral replication and preserved CD4+ Tcell numbers beyond that seen with orally administered native drugs. These investigations bring us one step closer toward using long-acting antiretrovirals in humans.

Long-acting, parenterally administered antiretroviral nanoformulations are of immediate need [1, 2]. Those who would benefit most are patients for whom drug adherence and availability are limited and/or those who cannot ingest drug formulations [2, 3], leading to viral resistance patterns [4]. As monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) are reservoirs for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and can uptake, transport, and release virus into infected tissues, our laboratory developed long-acting nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) in monocyte-macrophage carriers [5–11]. Surfactant composition, size, and charge of the particles were evaluated to optimize cell entry and release of atazanavir (ATV), ritonavir (RTV), and efavirenz (EFV) as these hydrophobic drugs are easily encased and commonly used in the clinic [7, 10–15]. Uptake and release of nanoART into and from MDMs were at drug levels at or beyond the half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) (EFV, 1.7–25 nM; RTV, 35–200 nM; ATV, 2–5 nM) [16] with limited or no cytotoxicity. On the basis of these outcomes, the most effective ART nanoformulations were selected for in vivo studies in HIV-1ADA–infected, nonobese diabetic, severe combined immunodeficient common cytokine receptor γ chain–deleted (NOD/scid-γcnull [NSG]) mice reconstituted with human peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) (PBL-NSG mice) [17]. Two schemes were used for testing. First, 1 dose of nanoART was injected subcutaneously 1 day before HIV-1ADA infection with replicate native drugs given orally. Second, PBL-NSG mice were infected with HIV-1ADA before subcutaneous administration of nanoART. ART activity was evaluated by determination of virus suppression and preservation of CD4+ T cells. HIV-1gag RNA by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in spleen and immunohistochemical quantitation of infected cells by staining for HIV-1p24 proteins were assessed with CD4+ T-lymphocyte numbers. Systemic toxicities were enhanced as a consequence of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). These results provide proof-of-concept that stable nanoART formulations provide sustained drug levels in serum and tissues above the EC50 and afford effective antiretroviral responses independent of ex vivo macrophage loadings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and Characterization of nanoART

Free base RTV and EFV were obtained from Shengda Pharmaceutical Co and Hetero Labs Ltd, respectively. ATV-sulfate was purchased from Gyma Laboratories of America Inc. The surfactant (excipient) used in generating all formulations was poloxamer-188 (P188; Sigma-Aldrich) with or without 1,2-distearoyl-phosphatidyl-ethanolamine-methyl-polyethyleneglycol conjugate-2000 (mPEG2000-DSPE, Genzyme Pharmaceuticals LLC). Final synthesis of the nanosuspension was achieved by either wet-milling or homogenization [18]. Drug levels were analyzed by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography [7, 10, 12] and by ultraperformance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC coupled to an Applied Biosystems 4000 Q TRAP quadruple linear ion trap hybrid mass spectrometer [19]. For scanning electron microscopic examinations of nanoparticles, 10 µL of nanosuspension was diluted in 1.5 mL of 0.2 µm filtered distilled water and prepared for morphologic examination using a Hitachi S4700 Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (Hitachi High Technologies America, Inc). Human MDM uptake, retention, release, and antiviral activity of nanoART in vitro were determined [10]. Scoring of nanoART, including the polydispersity index (PDI), in vitro activity (particle uptake, drug retention and release, and antiretroviral activity), cytotoxicity, and pharmacokinetics (PK), was made by assessment of decade-weighted ratios (DWRs) [10]. This was determined for each nanoformulation where an arbitrary maximal (best) score of 10 was assigned for each test performed. DWRs were calculated as areas under the curve (AUC) for each formulation, proportional to 10 AUC/AUCbest ratio. For example, a score of 9.7 reflected an 8-hour nanoART drug “uptake value” of 29.6 µg drug/106 cells of 97% when compared to a “best” test result of 30.5 µg/106 cells seen in all assays. The DWR for in vitro activity of each formulation reflected the averages of differences for nanoART uptake, retention, release, and antiretroviral activity in MDMs for each nanoART as compared to the best performer. DWRs have been described in detail previously[10]. Cell retention of drug was determined as drug remaining in the cell whereas drug release was the amount of drug released into media. Antiretroviral activity was determined over 15 days. Scoring for in vitro toxicity was calculated as the average of DWR based on highest alamarBlue (AbD Serotec) reduction and lowest macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α). DWR scoring of PK was determined in vivo as a function of the highest serum drug levels in nanoART-treated mice (250 mg/kg, subcutaneous). Final scores were composite averages of all tests.

Animals

Male NSG mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and housed in filter top cages with free access to food and water under a 12-hour/12-hour light/dark cycle in accordance with ethical guidelines for care of laboratory animals approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Human Cell Isolation, Transplantation, and Viral Infection

Human PBLs were purified from leukopaks by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation and used to reconstitute NSG mice [20]. PBLs were injected intraperitoneally into 8-week-old mice at 30 × 106 PBLs per mouse [21]. For viral infections, the HIV-1ADA strain was propagated in human MDMs and was found to be negative for endotoxin [22].

Biodistribution and Antiretroviral Activity of nanoART

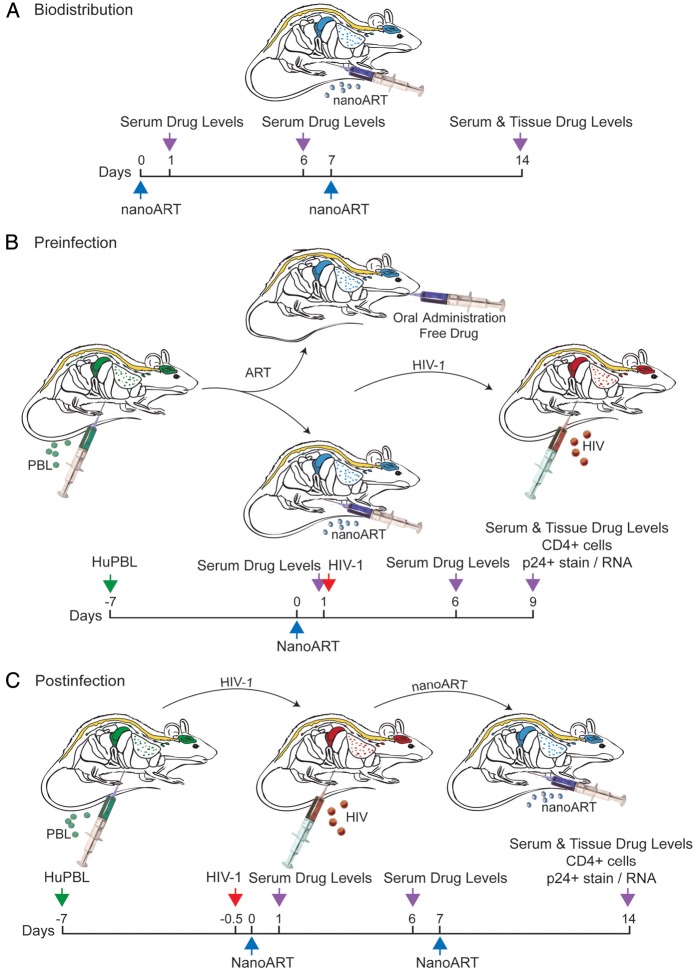

To determine dose-dependent serum drug concentrations and tissue distribution of nanoART, nonreconstituted NSG mice were injected subcutaneously on days 0 and 7 with nanoART (ATV and RTV at 80, 150, or 250 mg/kg). These corresponded to human doses of 6.5–20.3 mg/kg based on an interspecies scaling factor of 12.3 [23]. Blood samples were collected at days 1, 6, and 14 after drug administration (Figure 1A). At study end (14 days after initial injection), tissue samples were collected for drug biodistribution assay. NSG mice were reconstituted with PBLs 7 days prior to subcutaneous nanoparticle administration or oral drug delivery of native drugs (Figure 1B). One day after drug treatment, animals were infected intraperitoneally with HIV-1ADA at a dose of 104 median tissue culture infective dose per mouse. Animals were killed on day 9 after drug treatment, and blood and tissues collected for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) and viral load tests. PBL-reconstituted NSG mice were also infected with HIV-1ADA after 7 days. Two doses of nanoART were administered subcutaneously, the first dose at 12 hours (day 0) and the second at 7 days after infection. NanoART was administered as ATV and RTV at 250 mg/kg or ATV, RTV, and EFV at 100 mg/kg each drug (Figure 1C). Tissues were collected on day 14 for drug level determinations. Serum drug levels on days 1, 6, or 14 were assayed after submandibular or cardiac puncture bleeds. Tissues (liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and brain) were collected following phosphate buffered saline (PBS) body perfusion. Drug concentrations in serum and tissues were determined by UPLC-MS/MS [19].

Figure 1.

Experimental protocols used in studies of nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) efficacy and toxicology profiles. A, Treatment paradigm to determine pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of nanoART (M2001 [atazanavir, ATV] + M3001 [ritonavir, RTV]; 80, 150, or 250 mg/kg each drug) by subcutaneous administration to NSG mice on days 0 and 7. B, Treatment paradigm to determine preinfection antiviral activity of nanoART (H2001 [ATV] + H3001 [RTV]; 250 mg/kg each drug) by subcutaneous administration on day 0 to human peripheral blood lymphocyte (huPBL)–reconstituted NSG mice 24 h prior to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection. C, Treatment paradigm to determine antiviral activity of nanoART (H2001 + H3001, 250 mg/kg each drug or H2001 + H3001 + H4001 [efavirenz, EFV], 100 mg/kg each drug) by subcutaneous administration on days 0 and 7 to PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1–infected NSG mice.

Serum Biochemistry, Tissue Histopathology, and Immunohistochemical Tests

Alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, total serum calcium, and phosphate were determined in blood collected by cardiac puncture at 14 days after initial nanoART treatment using a VetScan comprehensive diagnostic profile disc (Abaxis Inc) and a VetScan VS-2 instrument. Tissue samples were collected on day 14, placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer-thick sections were cut and mounted on glass slides. For histopathological analysis, tissue sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological evaluations were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Society of Toxicologic Pathology. Immunohistochemical staining used mouse monoclonal antibodies (Dako) for HLA-DR (clone CR3/43, 1:100) and HIV-1p24 (clone, Kal-1, 1:10) and the polymer-based horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antimouse Dako EnVision systems were used for secondary detection, then developed with 3,3-diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were obtained with a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera fixed to a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope using NIS-Elements F 3.0 software (Nikon Instruments). The number of HIV-1p24+ cells per section was determined and expressed as the percentage of total HLA-DR+ cells. For HIV-1gag RNA measurements, RNA from spleen sections was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed to complementary DNA with random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), and quantitative RT-PCR was performed [24].

FACS Analyses of T-Cell Subsets

At study termination, blood samples were collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid–coated tubes (BD Diagnostics), and spleen cells were resuspended in PBS. Blood leukocyte and spleen cell suspensions were tested for expression of human CD45, CD3, CD4, and CD8 markers as 4-color combinations [25].

Statistical Analyses

Because of limitations in sample size, descriptive statistics used medians. Outcomes were compared between 2 groups using a Mann-Whitney test and data assessed among 3 or more groups using 1-way analysis of variance after performing a rank transformation on the variables. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using the Tukey method to adjust for multiple comparisons. A P value ≤.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of nanoART Formulations

The morphologic (shape), physicochemical (PDI and charge) and biologic characteristics (uptake, retention, release, and antiretroviral activity in MDMs) of the nanoARTs were assessed [7, 10, 12] (Figure 2). ATV nanoARTs were thin and rod-shaped whereas RTV nanoARTs were plumper particles. EFV particles were short and rectangular-shaped. Particle sizes ranged from 281 nm (M3001) to 470 nm (H4001) (Supplementary Table 1), with PDI being lower for homogenized than for wet-milled particles (0.200 [H2001] to 0.288 [M3001]). All particles were negatively charged (−31.6 mV [H3001] to −13.5 mV [M2001]). MDM uptake of the nanoparticles and intracellular retention and release were similar for wet-milled or homogenized formulations (Figure 2B). Antiretroviral efficacies of the nanoformulations in MDM infected with HIV-1ADA were drug-dependent [11].

Figure 2.

Morphology, in vitro activity, and tissue biodistribution of nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART). Serum drug and tissue levels in mice treated with 2 weekly injections of different doses of nanoART (atazanavir [ATV] and ritonavir [RTV]). A, Scanning electron micrographs (×15 000) of nanoformulations of ATV formulated by wet-milling (M3001) or homogenization (H3001), RTV formulated by wet-milling (M2001) or homogenization (H2001), and homogenized efavirenz (EFV) (H4001) on 0.2-µm polycarbonate filter membranes. Bar = 1 μm. B, Selection criteria for formulations used. P188, poloxamer 188; mPEG2000-DSPE, 1,2-distearoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine-methyl-polyethyleneglycol conjugate-2000; PDI, polydispersity index; PK, pharmacokinetics. aFormulations were produced by wet-milling (M) or high-pressure homogenization (H). bScoring of PDI, in vitro activity (MDM nanoART uptake, 15-day drug retention, drug release, and antiviral activities) and cytotoxicity (alamarBlue reduction and tumor necrosis factor α MDM production were determined as a decade weighted ratio (see Methods). Scoring of PK was determined as a function of the highest serum drug levels 7 days after nanoART administration (250 mg/kg subcutaneously) to BALB/cJ mice. Drug levels of ATV and RTV were determined from serum on days 1, 6, and 14 (C) and tissues on day 14 (D) after 2 weekly subcutaneous injections of combined nanoART (ATV/RTV; M2001 + M3001; 80, 150, or 250 mg/kg each) given to nonreconstituted, noninfected NSG mice on days 0 and 7. Data are expressed as median ± 25th (serum) and 75th (serum and tissues) percentiles for 5 mice per group. Differences were determined by analysis of variance of rank-transformed values and Tukey post hoc analysis. †Significantly different from values for other doses at that day or tissue at P ≤ .05.

Based on in vitro screening, the nanoART formulations M2001, H2001, M3001, H3001, and H4001 were selected for animal studies [6, 10, 18]. The “M” prefix designation in the formulation nomenclature refers to those produced by wet-milling, while the “H” refers to those prepared by homogenization (Figure 2B). Milled formulations performed within the top quartiles in uptake, retention, release, and antiretroviral efficacy tests in MDMs [10]; however, the formulations showed more limitations in size and PDI and greater toxicities as determined by decreased alamarBlue reduction and increased MDM TNF-α production (Figure 2B) [6, 11]. Formulations were administered to BALB/cJ mice in a pilot “survey.” A partial PK evaluation demonstrated that formulations containing the P188 surfactant produced sustained serum and tissue drug concentrations (Figure 2B; Supplementary Figure 1) through 7 days after injection. Taken together, these data serve as selection criteria for the P188-containing nanoformulations (M2001, H2001, M3001, H3001, and H4001) for use in the current animal investigations.

Nanotoxicology Profiling

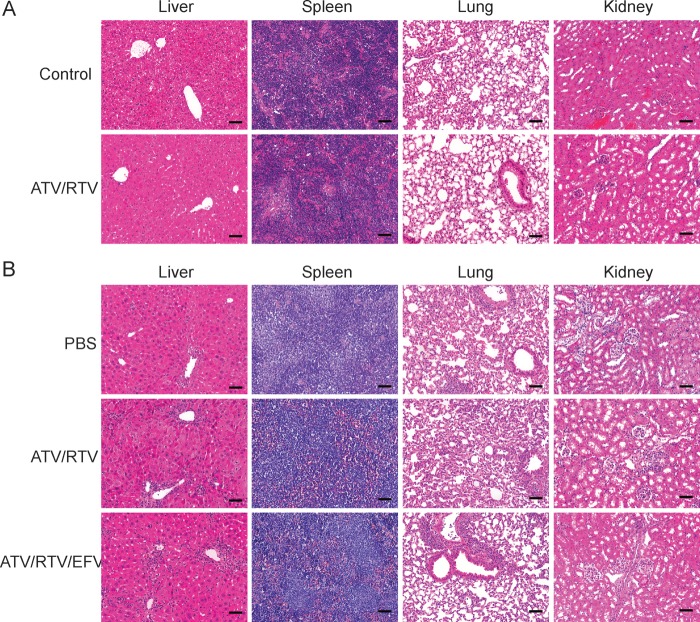

Serum chemistry metabolic profiling and tissue histopathological analyses were conducted in control NSG mice injected subcutaneously with M3001 and M2001 (combination ATV and RTV) at ≤250 mg/kg for each drug. Treatment was administered in 2 doses, on days 0 and 7. Normal serum chemistry profiles (Supplementary Table 2) were seen. Of interest, histopathology of both untreated and nanoART-treated mice showed minor extramedullary hematopoiesis [26] and uneven liver glycogenation. Supplemental studies, performed in normal BALB/cJ mice, showed a 2-fold increase and decrease in platelet counts and blood lymphocyte counts, respectively, at 14 days following treatment with 100 mg/kg nanoART (data not shown). The decline in lymphocyte counts was also observed following treatment with native drugs.

We next assessed whether PBL reconstitution and/or HIV-1 infection might exacerbate any nanoART toxicity. Thus, HIV-1–infected PBL-NSG mice were administered PBS (no drug); nanoART (ATV and RTV, 250 mg/kg, or ATV, RTV, and EFV, 100 mg/kg, subcutaneously) (Figure 1C). In PBS-treated, HIV-1–infected PBL-NSG mice, serum transaminase levels were approximately 2-fold (149.4 U/L) higher than normal (Supplementary Table 2). Histopathological assessment of liver sections confirmed substantive numbers of lymphocytes in the pericentral regions of PBS- and nanoART-treated mice (Figure 3B). A few necrotic hepatocytes were also observed, consistent with GVHD [27, 28].

Figure 3.

Tissue histology following nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) injections in mice. A, Hematoxylin and eosin staining of sections from liver, spleen, lung, and kidney in nonreconstituted, noninfected NSG mice treated with 2 weekly subcutaneous injections of 250 mg/kg each atazanavir (ATV)/ritonavir (RTV) (M3001 + M2001). B, Tissue histology of peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL)–reconstituted, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–infected NSG mice treated with 2 weekly subcutaneous injections of either ATV/RTV (H3001 and H2001, 250 mg/kg each) or ATV/RTV/efavirenz (EFV) (H3001, H2001, and H4001, 100 mg/kg each) or untreated (PBS). All images at ×200 magnification. Bar = 100 μm.

Pharmacodynamic Analyses

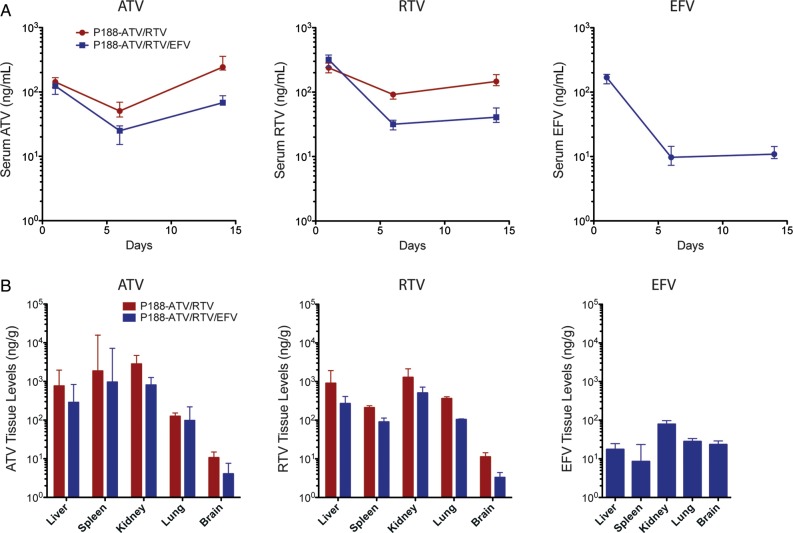

To determine the nanoART dose(s) required to achieve therapeutic serum drug concentrations, pharmacodynamic analyses were performed in normal NSG mice following subcutaneous administration of 80, 150, or 250 mg/kg ATV and RTV. Median drug concentrations declined 2 orders of magnitude (log10) from day 1 to day 6 (Figure 2C) and at day 6 were 94.8 ng/mL and 132 ng/mL, respectively, in the 250mg/kg-dose group. This drop was due to drug metabolism. Notably, ATV concentrations at day 14 were higher than day 6 levels. In the high-dose group, ATV concentrations at day 14 were 417 ng/mL above the median plasma concentrations seen in ATV-treated patients [29]. In contrast, there were no differences in serum concentrations of RTV at day 14 compared with day 6.

Corresponding tissue drug levels in nanoART-treated animals were determined at day 14. Livers of animals treated with 250 mg/kg nanoART contained 1656 ng/g ATV and 758 ng/g RTV (Figure 2D). ATV levels were 120–183 ng/g tissue in spleen, kidney, and lung. RTV levels were 276 and 264 ng/g tissue in spleen and kidney, respectively, and 141 ng/g in lung. Drug levels in brain were at the limit of detection. Of interest, ATV and RTV levels in liver, spleen, kidney, and lung differed by dose. On the basis of these results, a dose of 250 mg/kg ATV and RTV (H3001 and H2001) was chosen for assessment of antiviral efficacy. Here, NSG mice were reconstituted with human PBLs 7 days prior to a single does of nanoART, and 24 hours later were infected with HIV-1ADA. In the second experimental paradigm, nanoART was administered subcutaneously, 12 hours after HIV-1ADA infection (day 0) and again on day 7. Biodistribution studies were used to confirm that nanoART treatment achieves therapeutic serum concentrations of ATV in PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1–infected mice (Figure 4A). Serum ATV concentrations decreased from day 1 to day 6, but increased to 256 ng/mL and 88 ng/mL on day 14 in animals treated with ATV and RTV or ATV, RTV, and EFV, respectively. Of note, median ATV concentrations on day 14 in the ATV and RTV group were above the minimum effective ATV serum concentration for humans of 150 ng/mL [30]. Serum EFV concentration was 4–6-fold lower than that of RTV or ATV (Figure 4A) and was significantly lower than the minimal plasma therapeutic concentration of 1000 ng/mL [31].

Figure 4.

Serum and tissue drug levels in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)–infected peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL)–NSG mice treated with 2 weekly injections of nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) combinations (atazanavir [ATV] and ritonavir [RTV] or ATV, RTV, and efavirenz [EFV]). Following subcutaneous injections of either ATV and RTV (H3001 and H2001; 250 mg/kg each) or ATV, RTV, and EFV (H3001, H2001, and H4001; 100 mg/kg each) given on days 0 and 7 to PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1–infected mice, drug levels of ATV, RTV, and EFV were determined in serum on days 1, 6 and 14 (A), and in liver, spleen, kidney, lung, and brain on day 14 (B). Data are expressed as median ± 25th (serum) and 75th (serum and tissues) percentiles for 8 mice per group.

Next, we determined tissue drug levels in HIV-1–infected PBL-NSG mice on day 14 after nanoART treatment on days 0 and 7 (Figure 4B). In contrast to nanoART treatment in normal NSG mice (Figure 2D), median spleen ATV levels were 3-fold higher than in liver (Figure 4B). Spleen ATV levels were commonly variable and in several mice were 16 000–17 000 ng/g [27, 28]. Median liver ATV levels were 761 ng/g and 287 ng/g in animals treated with ATV and RTV and ATV, RTV, and EFV, respectively. In mice treated with ATV and RTV or ATV, RTV, and EFV, RTV levels were 3–4-fold higher in liver (900 ng/g and 268 ng/g, respectively) than in spleen (211 ng/g and 90 ng/g, respectively). Levels of drug (ATV and RTV with EFV) in the skin at the site of injection(s) were 1.1–1.6 mg drug per gram tissue serving as a potential depot for drug.

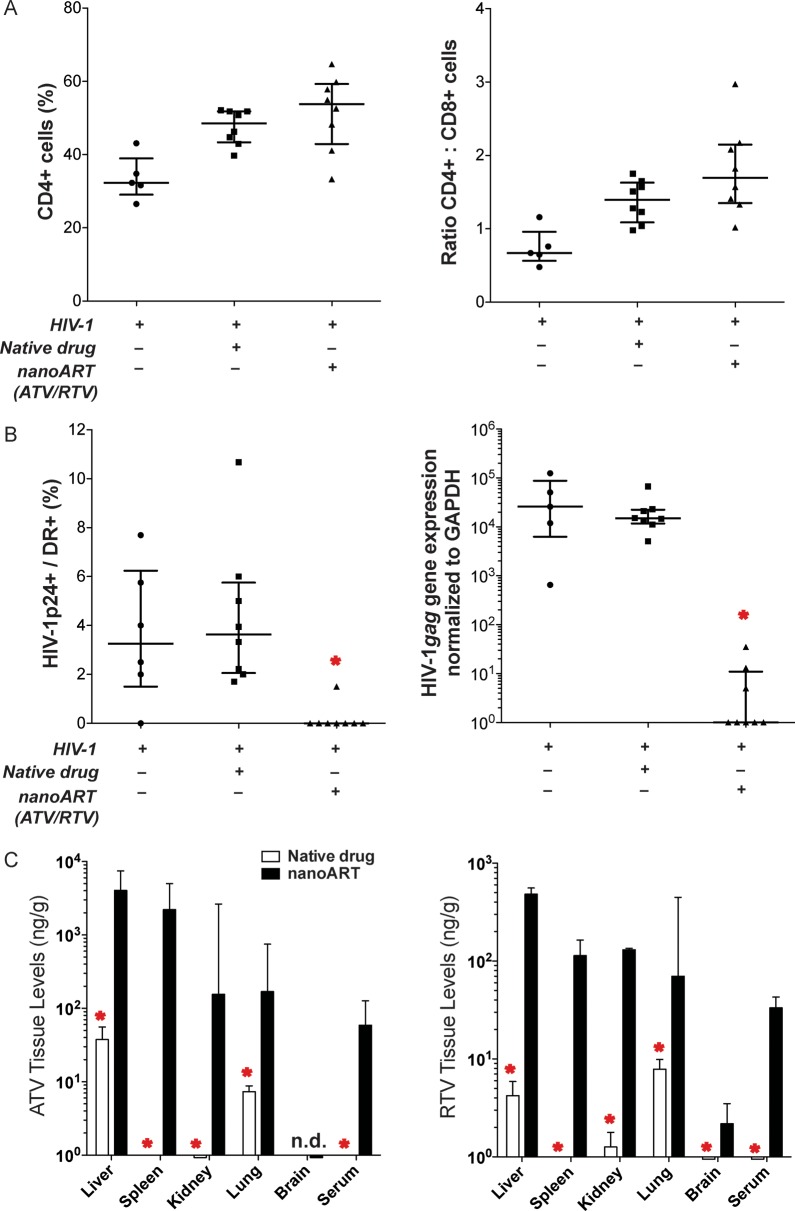

Antiviral Activities of nanoART Administered Before HIV-1 Infection

Antiviral activities of nanoART together with PK and biodistribution studies were performed. PBL-reconstituted NSG mice were treated with nanoART or native drugs 1 day prior to HIV-1 infection, and viral activity was determined 9 days after drug administration. HIV-1 infection results in loss of human CD4+ T cells in PBL-reconstituted immunodeficient mice [21, 32–35]. Thus, as an indicator of viral infection, levels of human CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as percentages of total human CD3+ T cells and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios were determined from FACS analyses of spleen cells taken at study termination (9 days after drug treatment). Levels of human CD45+ T cells were similar in all treatment groups (1.7% ± 0.4%, 2.2% ± 0.4%, and 1.4% ± 0.3% of total cells for PBS-, native drug-, and nanoART-treated mice, respectively). Low spleen CD4+ T cells and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios were observed in PBS-treated HIV-1–infected animals (Figure 5A). To determine the level of HIV-1 infection, HIV-1p24 expression among HLA-DR+ cells in spleen was determined. NanoART treatment significantly reduced HIV-1p24+ cells in the spleen and reduced spleen HIV-1gag gene expression (Figure 5B). In contrast, treatment with native drug did not decrease the number or expression levels of HIV-1p24+ cells in the spleen. At day 9, drug levels in serum and peripheral tissues were higher in nanoART-treated mice than in those given native drug (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Antiretroviral activities of nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) administered prior to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) exposure. NanoART was delivered on day 0 as a combination of atazanavir (ATV) and ritonavir (RTV) (250 mg/kg each H3001 and H2001, subcutaneously) to peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL)–reconstituted NSG mice. Native drugs (250 mg/kg each ATV and RTV in PBS) were delivered by oral gavage on day 0. Mice were infected with HIV-1ADA on day 1. Spleens were harvested on day 9 after drug injection. A, Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis shows the percentage of human CD4+ among total CD3+ T cells (left panel) and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios (right panel) for spleens from individual mice. B, Percentages of HIV-1p24–expressing cells among human HLA-DR+ cells were determined from cell counts of immunohistochemistry from splenic tissues (left panel). HIV-1gag RNA expression normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA expression in spleen (right panel). A and B, Data are shown as individual data points and median ± 25th and 75th percentiles (bar ± whisker) for 5–8 mice per group, analysis of variance of rank-transformed values, and significant differences determined by Tukey post hoc analyses, whereby P < .01 compared to native drug–treated, PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1–infected mice. C, Tissue and serum drug levels of ATV (left panel) and RTV (right panel) on day 9 following subcutaneous injection of nanoART or native drugs to mice. Data are expressed as median ± 25th (serum) and 75th (serum and tissue) percentiles for 8 mice per group, analyzed by Mann-Whitney test and significant differences determined by Tukey post hoc analyses. *Significantly different from nanoART-treated, PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1–infected NSG mice at P ≤ .01.

Suppression of Acute HIV-1 Infection by nanoART

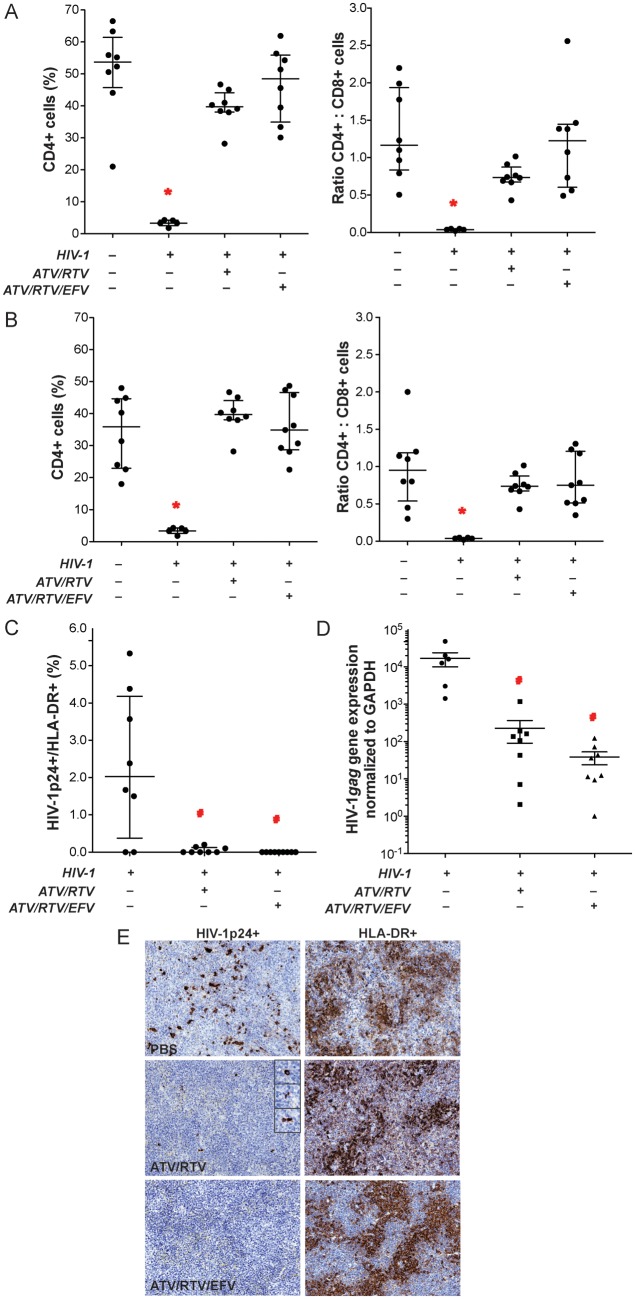

To determine whether nanoART could suppress preexisting HIV infection, HIV-1–infected PBL-NSG mice were treated with nanoART 12 hours and 7 days after infection, then sacrificed on day 14. Levels of human CD45+ T cells (as percentage of total cells in peripheral blood and spleen [blood, 59.2% ± 6.5% to 73.9% ± 2.9%; spleen, 22.3% ± 7.2% to 29.8% ± 4.9%]) did not differ significantly among treatment groups. In HIV-1–infected animals not treated with nanoART, percentages of CD4+ T cells and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios were significantly decreased in both peripheral blood (Figure 6A) and spleen (Figure 6B) compared with uninfected animals. Importantly, in nanoART-treated (ATV/RTV or ATV/RTV/EFV) HIV-1–infected animals, there was no difference in levels of CD4+ T cells and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios from those observed in uninfected mice. The level of HIV infection was determined by immunohistochemical quantitation of HIV-1p24–expressing cells among HLA-DR+ cells in spleen. Both ATV/RTV and ATV/RTV/EFV treatments significantly reduced the number of HIV-1p24+ stained cells in the spleen, although a few were detected in some sections from the ATV and RTV treatment group (Figure 6C and 6E). Suppression of HIV-1 replication was also determined in spleen by PCR measurements for HIV-1gag gene expression. Treatment with ATV/RTV and ATV/RTV/EFV reduced viral gene expression by 2 and 3 orders of magnitude (log10), respectively (Figure 6D), although the difference between the 2 treatments was not statistically significant. Taken together, these results demonstrate that weekly dosing with nanoART can reduce HIV-1 viral infection to nearly undetectable levels.

Figure 6.

Antiretroviral activities of nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART). NanoART was delivered on days 0 and 7 as a combination of atazanavir (ATV) and ritonavir (RTV) (250 mg/kg each H3001 and H2001, subcutaneously) or a combination of ATV, RTV, and efavirenz (EFV) (100 mg/kg each H3001, H2001, and H4001, subcutaneously) to peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL)–NSG mice infected intraperitoneally with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)ADA 12 h before initial nanoART dose. Peripheral blood and spleens were collected on day 14 after initial nanoART injection. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analyses show the percentage of human CD4+ among total CD3+ T cells (left panels) and CD4+/CD8+ T-cell ratios (right panels) for peripheral blood (A) and spleen (B) from individual mice. C, Percentages of HIV-1p24–expressing cells among human HLA-DR+ cells were determined from cell counts of immunostained serial sections through spleens of PBL-reconstituted, HIV-1ADA–infected PBL-NSG mice. D, HIV-1gag RNA expression in spleen normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) messenger RNA expression. E, Expression of human HLA-DR and HIV-1p24 in alternate serial sections of splenic tissues from HIV-1–infected NSG mice treated with PBS vehicle (top panels), ATV and RTV (middle panels), or ATV, RTV, and EFV (bottom panels). Spleens were collected on day 14 after initial nanoART injection, sectioned, immunostained with antibodies specific for HLA-DR or HIV-1p24, followed by secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, and were visualized by 3,3-diaminobenzidine . A–D, Data are shown as individual data points and median ± 25th and 75th percentiles (bar ± whisker) for 3–8 mice per group, analyzed by analysis of variance of rank-transformed values and significant differences determined by Tukey post hoc analysis, whereby P ≤ .05 compared to (*) nontreated, nonreconstituted, noninfected NSG mice and (#) nontreated, HIV-1–infected PBL-NSG mice.

DISCUSSION

We manufactured injectable long-acting antiretroviral combinations and tested them in a disease-relevant animal system. Our data demonstrate that nanoformulations of commonly used protease inhibitors that show efficacy in cell-based laboratory tests [7, 10] can be used successfully in rodent models of HIV-1 disease to halt loss of CD4+ T cells and attenuate viral replication. The results are in line with drug concentrations detected in sera and tissue. Toxicology profiles reveal that the drugs are well-tolerated.

The need for alternative antiretroviral formulations is clear based on complexities of many existing regimens, difficulties with adherence, lack of targeting viral reservoirs, emergence of drug resistance, and toxicities [2, 13]. Moreover, in patients who abuse drugs and show poor adherence to ART regimens, acclerated virologic resistance and transmission can be seen [36]. Adding to such concerns is the availability of ART in resource-limited settings [37–39]. Thus, the need for alternative therapies is timely [30, 40].

Cell-mediated drug delivery is a novel concept that employs intracellular recycling and late endosomes as reservoirs for drug [8]. Monocyte-macrophages offer a particularly attractive cell delivery system. Although the role played by macrophages in the current study is not certain, the established reservoirs and drug stability suggest that these cells serve as nanoparticle depots. Moreover, the observation that drugs delivered by nanoformulations can be stored in recycling endosomal compartments in macrophages may explain the observed long-acting nature of the drugs [9]. Although the promise of cell-mediated delivery of drugs is real, its perils demand equal consideration. This includes immune reactions elicited against the particle, untoward reactions against the excipients, and effects on the cell and tissues, as well as effects on its function consequent to harboring the crystal for periods of weeks [41, 42].

Also limitations are acknowledged in the experimental approach. For example, NSG mice as recipients of human PBLs commonly develop GVHD [27]. Thus, it is difficult to draw a firm conclusion on any nanoART hepatic toxicities in these animals. Nonetheless, such systems, as developed in this report, represent a new strategy for treating HIV-1 disease. The further design of nanoparticle carriers for such drug delivery may include decorating the particle with specific cell ligands that target virus-infected cell surface antigens. Moreover, the particle compositions used in these studies make nanoART translation to humans viable. Taken together, targeted drug delivery and ease of access to ART as nanoformulated medicines are real and convincing and demand further investigation for human use.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/jid/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Tanuja Gutti, Jaclyn Knibbe, and Ram Veerhubhotla for their expert technical assistance; Michel Kanmogne for statistical support; and Drs Han Chen and You Zhou of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln electron microscopy core for assistance with the scanning electron microscopy.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant numbers 1P01 DA028555, 2R01 NS034239, 2R37 NS36126, P01 NS31492, P20RR 15635, P01MH64570, and P01 NS43985 [to H. E. G.]) and by a research grant from Baxter Healthcare.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Broder MS, Chang EY, Bentley TG, Juday T, Uy J. Cost effectiveness of atazanavir-ritonavir versus lopinavir-ritonavir in treatment-naive human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the United States. J Med Econ. 2011;14:167–78. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2011.554932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swindells S, Flexner C, Fletcher CV, Jacobson JM. The critical need for alternative antiretroviral formulations, and obstacles to their development. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:669–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chesney MA, Ickovics J, Hecht FM, Sikipa G, Rabkin J. Adherence: a necessity for successful HIV combination therapy. AIDS. 1999;13(suppl A):S271–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braithwaite RS, Shechter S, Roberts MS, et al. Explaining variability in the relationship between antiretroviral adherence and HIV mutation accumulation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:1036–43. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batrakova EV, Li S, Brynskikh AM, et al. Effects of pluronic and doxorubicin on drug uptake, cellular metabolism, apoptosis and tumor inhibition in animal models of MDR cancers. J Control Release. 2010;143:290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressani RF, Nowacek AS, Singh S, et al. Pharmacotoxicology of monocyte-macrophage nanoformulated antiretroviral drug uptake and carriage. Nanotoxicology. 2011;5:592–605. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.541292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowacek AS, McMillan J, Miller R, Anderson A, Rabinow B, Gendelman HE. Nanoformulated antiretroviral drug combinations extend drug release and antiretroviral responses in HIV-1-infected macrophages: implications for neuroAIDS therapeutics. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2010;5:592–601. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9198-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batrakova EV, Gendelman HE, Kabanov AV. Cell-mediated drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2011;8:415–33. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2011.559457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadiu I, Nowacek A, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Macrophage endocytic trafficking of antiretroviral nanoparticles. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2011;6:975–94. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowacek AS, Balkundi S, McMillan J, et al. Analyses of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug charge, size, shape and content for uptake, drug release and antiviral activities in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Control Release. 2011;150:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balkundi S, Nowacek AS, Veerhubotla RS, et al. Comparative manufacture and cell-based delivery of antiretroviral nanoformulations. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;6:3393–3404. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nowacek AS, Miller RL, McMillan J, et al. NanoART synthesis, characterization, uptake, release and toxicology for human monocyte-macrophage drug delivery. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2009;4:903–17. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nowacek A, Gendelman HE. NanoART, neuroAIDS and CNS drug delivery. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2009;4:557–74. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dou H, Grotepas CB, McMillan JM, et al. Macrophage delivery of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug to the brain in a murine model of neuroAIDS. J Immunol. 2009;183:661–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dou H, Destache CJ, Morehead JR, et al. Development of a macrophage-based nanoparticle platform for antiretroviral drug delivery. Blood. 2006;108:2827–35. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-012534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson BS, Riccardi KA, Gong YF, et al. BMS-232632, a highly potent human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor that can be used in combination with other available antiretroviral agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2093–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2093-2099.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berges BK, Rowan MR. The utility of the new generation of humanized mice to study HIV-1 infection: transmission, prevention, pathogenesis, and treatment. Retrovirology. 2011;8:65. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-8-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balkundi S, Nowacek AS, Roy U, Martinez-Skinner A, McMillan J, Gendelman HE. Methods development for blood borne macrophage carriage of nanoformulated antiretroviral drugs. J Vis Exp. 2010 doi: 10.3791/2460. (46) pii:2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J, Gautam N, Bathena SP, et al. UPLC-MS/MS quantification of nanoformulated ritonavir, indinavir, atazanavir, and efavirenz in mouse serum and tissues. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gendelman HE, Orenstein JM, Martin MA, et al. Efficient isolation and propagation of human immunodeficiency virus on recombinant colony-stimulating factor 1-treated monocytes. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1428–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poluektova LY, Munn DH, Persidsky Y, Gendelman HE. Generation of cytotoxic T cells against virus-infected human brain macrophages in a murine model of HIV-1 encephalitis. J Immunol. 2002;168:3941–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gendelman HE, Genis P, Jett M, Zhai QH, Nottet HS. An experimental model system for HIV-1-induced brain injury. Adv Neuroimmunol. 1994;4:189–93. doi: 10.1016/s0960-5428(06)80256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoddart CA, Bales CA, Bare JC, et al. Validation of the SCID-hu Thy/Liv mouse model with four classes of licensed antiretrovirals. PLoS One. 2007;2:e655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poluektova L, Gorantla S, Faraci J, Birusingh K, Dou H, Gendelman HE. Neuroregulatory events follow adaptive immune-mediated elimination of HIV-1-infected macrophages: studies in a murine model of viral encephalitis. J Immunol. 2004;172:7610–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gorantla S, Makarov E, Finke-Dwyer J, et al. CD8+ cell depletion accelerates HIV-1 immunopathology in humanized mice. J Immunol. 2010;184:7082–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohbo K, Suda T, Hashiyama M, et al. Modulation of hematopoiesis in mice with a truncated mutant of the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain. Blood. 1996;87:956–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pino S, Brehm MA, Covassin-Barberis L, et al. Development of novel major histocompatibility complex class I and class II-deficient NOD-SCID IL2R gamma chain knockout mice for modeling human xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;602:105–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-058-8_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King MA, Covassin L, Brehm MA, et al. Human peripheral blood leucocyte non-obese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain gene mouse model of xenogeneic graft-versus-host-like disease and the role of host major histocompatibility complex. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;157:104–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Best BM, Letendre SL, Brigid E, et al. Low atazanavir concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid. AIDS. 2009;23:83–7. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328317a702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. AIDSinfo Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf. Accessed 2 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez-Cortes LF, Ruiz-Valderas R, Marin-Niebla A, Pascual-Carrasco R, Rodriguez-Diez M, Lucero-Munoz MJ. Therapeutic drug monitoring of efavirenz: trough levels cannot be estimated on the basis of earlier plasma determinations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:551–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosier DE. Distinct rate and patterns of human CD4+ T-cell depletion in hu-PBL-SCID mice infected with different isolates of the human immunodeficiency virus. J Clin Immunol. 1995;15:130S–3S. doi: 10.1007/BF01540903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, MacIsaac PD, Torbett BE, Levy JA. Rapid loss of CD4+ T cells in human-PBL-SCID mice by noncytopathic HIV isolates. Science. 1993;260:689–92. doi: 10.1126/science.8097595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorantla S, Santos K, Meyer V, et al. Human dendritic cells transduced with herpes simplex virus amplicons encoding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp120 elicit adaptive immune responses from human cells engrafted into NOD/SCID mice and confer partial protection against HIV-1 challenge. J Virol. 2005;79:2124–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2124-2132.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorantla S, Sneller H, Walters L, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathobiology studied in humanized BALB/c-Rag2-/-gammac-/- mice. J Virol. 2007;81:2700–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02010-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, et al. Rates of antiretroviral resistance among HIV-infected patients with and without a history of injection drug use. AIDS. 2005;19:1189–95. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000176219.48484.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilks CF, Crowley S, Ekpini R, et al. The WHO public-health approach to antiretroviral treatment against HIV in resource-limited settings. Lancet. 2006;368:505–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69158-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brinkhof MW, Pujades-Rodriguez M, Egger M. Mortality of patients lost to follow-up in antiretroviral treatment programmes in resource-limited settings: systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: recommendations for a public health approach, 2006 revision. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/artadultguidelines.pdf. Accessed 17 November 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huff-Rousselle M, Simooya O, Kabwe V, et al. Pharmacovigilance and new essential drugs in Africa: Zambia draws lessons from its own experiences and beyond. Glob Public Health. 2007;2:184–203. doi: 10.1080/17441690601063299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabanov AV, Gendelman HE. Nanomedicine in the diagnosis and therapy of neurodegenerative disorders. Prog Polym Sci. 2007;32:1054–82. doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gendelman HE, Kabanov A, Linder J. The promise and perils of CNS drug delivery: a video debate. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:58. doi: 10.1007/s11481-008-9103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.