Abstract

We differentiated mouse bone marrow cells in the presence of recombinant macrophage colony stimulating (rM-CSF) factor for 14 days during the flight of space shuttle Space Transportation System (STS)-126. We tested the hypothesis that the receptor expression for M-CSF, c-Fms was reduced. We used flow cytometry to assess molecules on cells that were preserved during flight to define the differentiation state of the developing bone marrow macrophages; including CD11b, CD31, CD44, Ly6C, Ly6G, F4/80, Mac2, c-Fos as well as c-Fms. In addition, RNA was preserved during the flight and was used to perform a gene microarray. We found that there were significant differences in the number of macrophages that developed in space compared to controls maintained on Earth. We found that there were significant changes in the distribution of cells that expressed CD11b, CD31, F4/80, Mac2, Ly6C and c-Fos. However, there were no changes in c-Fms expression and no consistent pattern of advanced or retarded differentiation during space flight. We also found a pattern of transcript levels that would be consistent with a relatively normal differentiation outcome but increased proliferation by the bone marrow macrophages that were assayed after 14 days of space flight. There also was a surprising pattern of space flight influence on genes of the coagulation pathway. These data confirm that a space flight can have an impact on the in vitro development of macrophages from mouse bone marrow cells.

Keywords: Gene expression, Differentiation, Macrophage colony stimulating factors, STS-126

1. Introduction

Although the value of the space shuttle has been controversial (Charles, 2011), one of the accomplishments of the space-shuttle era has been to establish that there are profound physiological changes during space flight (Chapes, 2004; Charles, 2011; Fagette et al., 1999; Harris et al., 2000; Ronca and Alberts, 2000; Stowe et al., 2003; Suda, 1998). In particular, we have evidence that space flight suppresses hematopoietic differentiation of macrophages and other blood cells (Ichiki et al., 1996; Sonnenfeld et al., 1992; Sonnenfeld et al., 1990; Vacek et al., 1983). Space flight has been found to decrease blood monocytes in circulation (Taylor et al., 1986), induce monocytes lacking insulin growth factor receptors (Meehan et al., 1992), and it changes leukocyte subpopulations in the bone marrow and spleen (Baqai et al., 2009; Gridley et al., 2009; Ortega et al., 2009; Pecaut et al., 2003). Decreases in the expression of the GM-CSF receptor may explain some of the in vivo physiological changes in macrophages that have been observed (Kaur et al., 2005).

Space flight experiments with rodents also have revealed a diminution in the percentage and number of early blast cells (CFU-GM) in bone marrow (Sonnenfeld et al., 1990, 1992). There were also increases in the number of CD34+ cells in the bone marrow of mice assessed after the flight of STS-108 (Pecaut et al., 2003). Skeletal unloading, using antiorthostatic suspension, simulates some of the physiological changes associated with space flight (Chapes et al., 1993; Morey-Holton and Globus, 1998, 2002) also diminishes the number of macrophage progenitor cells in the bone marrow and affects hematopoiesis (Armstrong et al., 1993, 1994, 1995a; Dunn et al., 1983, 1985; Sonnenfeld et al., 1992). Therefore, there are important health issues that might arise from space flight impacts on hematopoiesis.

Space flight affects cells by inducing broad physiological changes and/or it can have direct gravitational impacts on the cells themselves (Todd, 1989). We previously addressed the direct impact of space flight on macrophage differentiation at the cellular level on three different space shuttle flights (Space Transportation System (STS)-57, 60 and 62). There was increased mouse bone marrow macrophage proliferation and inhibited differentiation based on changes in expression of MHCII and Mac2 surface molecules (Armstrong et al., 1995b). Because these studies were done at less than optimal physiological temperatures (22.5–27.0 °C), there were some questions about the impact of these conditions on the outcome.

During the flight of the space shuttle Endeavour, STS-126, we had an opportunity to re-examine macrophage growth and differentiation from stem cells at optimal physiological temperatures (37 °C). This experiment allowed us to assess bone marrow differentiation in vitro in the absence of the complex in vivo environment. In particular, we tested the hypothesis that changes in the receptor for macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) may have been responsible for the effects of space flight on bone marrow macrophage differentiation. We also had an opportunity to assess global changes in transcript levels to provide insights about biochemical processes that may have been perturbed during the differentiation process.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies

Fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated- (FITC-) anti Ly6C (Clone AL-21), FITC-anti IgM (Clone RA-22), Phycoerythrin conjugated- (PE-) anti CD31 (Clone MEC13.3), PE- anti IgG2a (Clone R35-95), PE- anti CD44 (Clone IM7), PE- anti IgG2b (Clone A95-1), Allophycocyanin conjugated- (APC-) anti CD3 (Clone 145-2C11), and APC- anti IgG1 were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Jose California, CA). Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated-(AF647)– anti Mac2 (Clone eBioM3/38), AF647- anti IgG2a (Clone eBR2a), PE- anti CD11b (Clone M1-70), PE- anti IgG2b (Clone eB149/0H5), PE- anti Ly6G (Clone RB6-8C5), PE- anti IgG2b (Clone eB149/0H5), APC- anti F4/80 (Clone BM8), and APC- anti IgG2a (Clone eBR2a) were purchased from eBioscience Inc. (San Diego, CA). Purifiedanti c-Fms (Clone 20), purified – anti IgG, PE- anti IgG, PE- anti c-Fos (Clone 4) and PE- anti IgG2b (Clone not categorized) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA).

2.2. Bone marrow cells and assay set up

Bone marrow cells were harvested from humeri, femora, and tibiae of adult C57BL/6 mice (>8-week old; n = 21) originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred in the animal facility at Kansas State University (KSU) (Armstrong et al., 1993). All animal experiments were approved by Kansas State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, the bones were recovered and cleaned of all nonosseous tissue. The marrow cavity was flushed with a sterile PBS solution. The red blood cells were lysed by incubating in ammonium chloride lysis buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, and 0.1 mM Na2EDTA, pH 7.3) for 5 min at 4 °C. Pooled cells were centrifuged (300 × g, 5 min) and washed two times with Dulbecco’s Modified Minimal Essentials Medium (Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT) containing 1% fetal bovine serum, 1% Nu serum (BD, Bedford, MA), Glutamine plus (2 mM, Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), 0.1 M HEPES and 10% Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Grand Island, N.Y.)(DMEM2). Primary bone marrow cells were suspended in DMEM2 supplemented with recombinant mouse macrophage colony stimulating factor (rmM-CSF; 1.5 ug/ml, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in preparation for culture in Fluid Processing Apparatus hardware (FPAs; Fig. 1B) (Armstrong et al., 1995b; Hoehn et al., 2004; Luttges, 1992; Wilson et al., 2007). Briefly, FPAs are 11.70 cm long and 1.35 cm diameter (1.31 mm glass thickness) glass barrels. The FPAs have a bypass which allows for the transfer of media from one chamber to another. The FPAs were siliconized with Rain-X (Blue Coral-Slick 50, Ltd; Cleveland, OH) and fitted with a previously siliconized rubber septum, 1.2 cm from the distal end of the barrel. Bacti-caps (16-mm diam.; Oxford Labware, St. Louis, MO) were placed on the proximal end of the FPAs before sterilization.

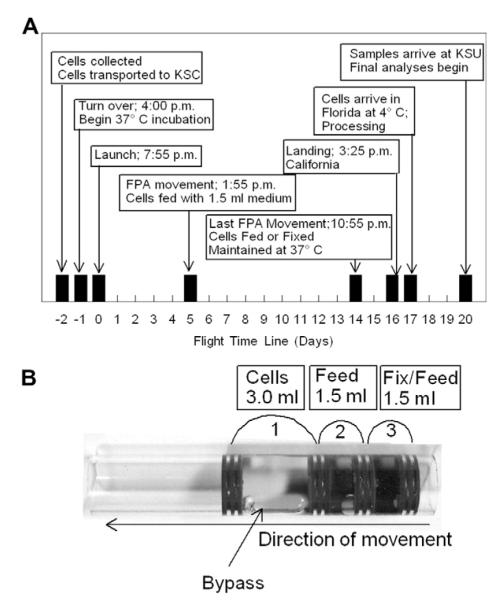

Fig. 1.

A. Time-line of activities for bone marrow macrophage differentiation on STS-126. B. Fluid Processing Apparatus (FPA). 3.0 ml of cells were placed in a chamber 1 separated by two rubber septa. The FPA is engineered with a bypass so that when the internal assembly of septa and biological samples are pushed to the left the medium in the second chamber will mix with the material in chamber 1 and septa 2 and 3 will compress. Septa 3 and 4 also compress with additional movement to mix the contents of chamber 3 with the contents previously mixed.

The bone marrow cells were loaded into the primary chamber of 48 FPAs (1 × 107 cells per 3 ml DMEM2 supplemented with rmM-CSF). A second chamber was formed by sliding a sterile, siliconized septum parallel to the first septum. Excess air was evacuated through a 26GA needle. DMEM2 supplemented rmM-CSF was loaded into the second chamber of all 48 FPAs. A third chamber was formed by adding an additional septum similarly to the second. Thirty-two FPAs were loaded with 8% formalin. Eight FPAs were loaded with 6.0 M guanidinium isothiocyanate (GITC) (Woods and Chapes, 1994) and 8 FPAs were loaded with DMEM2 plus rmM-CSF (returned as viable cultures). The third chambers were sealed with septa as described above. The FPAs were transported (day-2 of spaceflight, Fig. 1A) at 4 °C to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Space Life Sciences Laboratory Facility (SLSL) at Kennedy Space Center (KSC). The FPAs were loaded into 6 Group Activation Packs (GAPs) (Hoehn, Klaus, 2004), 8 FPAs/GAP. GAPs were placed into the Commercial Generic Bioprocessing Apparatus (CGBA) (Hoehn et al., 2004; Woods and Chapes, 1994)) at 37 °C to start incubation. Parallel temperature and activation profile conditions were maintained on GAPs kept at the SLSL. The incubation was started before the launch of space shuttle (Endeavour) flight Space Transportation System (STS)-126 (day -1 of spaceflight,Fig. 1A). On day 6 of cell differentiation (day 5 of spaceflight, Fig. 1), 1.5 ml of DMEM2 supplemented with rmM-CSF was added to the cell suspension by mixing chambers 1 and 2 of the FPAs through the bypass (Hoehn et al., 2004). On day 15 of cell differentiation (day 14 of spaceflight) the content of the FPAs third chamber was mixed with the cell suspension in the previously merged chambers. STS-126 landing occurred in California 17 days after the start of 37 °C cell culture incubation (day 16 of spaceflight). Samples were placed at 4 °C and transported to SLSL in Florida. The FPAs were unloaded from GAPs, inspected, and the cells in medium were collected from 8 FPAs and viable cells (trypan blue exclusion) were counted on a hemacytometer. Cell-free media were collected from these FPA and were frozen and sent to KSU. Glucose content was measured in each sample using a digital glucometer (Home Diagnostics, Inc., Ft. Lauderdale, FL). FPAs prepared to fix cells in formalin or GITC were transported to KSU at 4 °C and were processed 19 days after the cells were place at 37 °C to begin differentiation. Total cell counts were done on formalin-fixed cells.

2.3. Flow cytometry

At KSU, bone marrow cells fixed in formalin were washed in Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS) and counted and cell concentrations were adjusted to 1 × 107 cells per ml. Phenotypic analysis of bone marrow-derived cells was performed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting as has been described previously by our group (Ortega et al., 2009; Potts et al., 2008). Five hundred thousand bone marrow cells were blocked with PBS:goat serum (50:50; 50 μl) at 4 °C for 0.5 h. AF647- anti Mac2 or anti IgG2a (0.5 μg), FITC- anti Ly6C or anti IgM (0.5 μg), PE- anti CD11b or anti IgG2b (0.1 μg) , APC- anti CD31 or anti IgG2a (0.5 μg), APC- anti CD3 or anti IgG1 (1 μg), PE- anti Ly6G or anti IgG2b (0.1 μg), APC- anti F4/80 or anti IgG2a (1.4 μg), PE- anti CD44 or anti IgG2b (1 μg), purified- anti c-Fms or anti IgG (0.25 μg), and PE- anti c-Fos or anti IgG2b (3.8 μg) were added to the cell suspensions and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. In some instances, multiplexing of antibodies with compatible flurochromes was done (e.g. c-Fos and CD31 or Ly6C and CD31). The cells were then washed twice in HBSS and resuspended in HBSS containing 1% formalin. Cells were analyzed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickson. Rockville, MD) and a minimum of 20,000 events were collected for each sample.

2.4. Microarray analysis

At KSU, bone marrow cells preserved in GITC were combined in pools of 2 FPAs per sample to provide four independent flight and four ground samples for assessment. RNA was phenol extracted and purified in the aqueous phase using phase-lock tubes (5-prime, Gaithersburg, MD) centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min. RNA was ethanol precipitated and DNase treated (Qiagen RNeasy). Frozen RNA was sent to the University of Kansas microarray facility at the University of Kansas Medical Center (Kansas City, KS). At the facility, RNA concentrations and qualities were analyzed with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and RNA 6000 pico assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Based on RNA quality, the four best RNA samples were selected (Flight A 21.2 ng, RNA Integrity Value (RIN), 3; Flight D 25 ng, RIN, 3; Ground B 12.5 ng, RIN, 3; Ground D 24.1 ng, RIN, 3). All available RNA was concentrated and processed for target labeling using the 2x IVT labeling protocol. Briefly, the two round RNA amplification and labeling procedure was performed using the Affymetrix Small Sample Labeling Protocol vII (2xIVT) as follows: 50 ng of total RNA was primed with T7-oligo(dT) promoter primer (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and reverse transcribed using SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase vII kit (Invitrogen). The first round of RNA amplification was performed on the cDNA using the MEGAScript T7 Invitro-Transciption kit (Ambion). Amplified RNA (aRNA) was reverse transcribed using random primers and SuperScript Reverse Transcriptase vII kit. The second round RNA amplification and biotin labeling was conducted using the GeneChip 3′ IVT labeling kit (Affymetrix). Biotin labeled aRNA was fragmented and hybridized to the GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0, 3′ expression array (Affymetrix) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Array washing and staining was conducted using the GeneChip Fluidics Station 450 followed by a 1x scan with the GeneChip 3000 Scanner 7G with Autoloader. GeneChip processing and data collection was performed using GeneChip Operating System v1.4 (GCOS). Probe intensities were consistent amongst the 4 samples and correlation coefficients among the samples were all greater than 0.95.

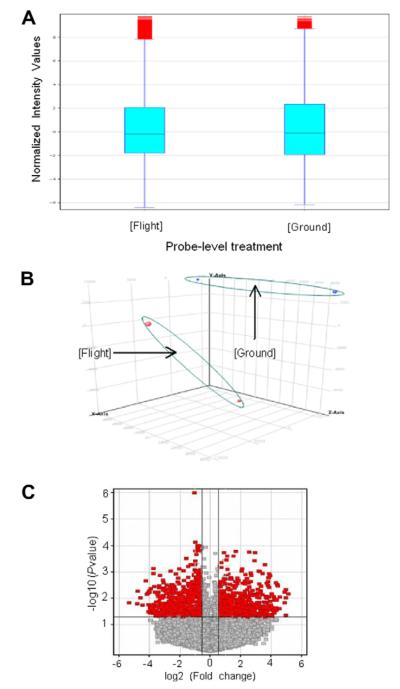

Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 CHP files were imported into GeneSpring GX11 and were transformed to log2 based to create a Flight vs. Ground data comparison. We performed gene-level analysis with Advanced Workflow with GeneSpring software. A 50 percentile shift normalization algorithm (Yang et al., 2002) was applied to the samples. The correlation coefficients within each treatment group were between 0.9759831 and 0.9926981. The box plot (Fig. 2A) of Flight and Ground groups shows some extreme values above the maximum value in both data sets. From the Principal Component Analysis plot (Fig. 2B), we confirmed some sample-to-sample variation but there were additional variable differences between Flight and Ground treatments. ANOVA without Multiple Testing Correction was applied and 1678 significant genes out of 28,972 total genes were selected at a p-value < 0.05 with up or down gene-level fold changes greater than 1.5 (Fig. 2C)(Dudoit et al., 2002). To reduce the Type I Error, we performed ANOVA again with the Benjamini Hochberg FDR of Multiple Testing Correction method with cut-off 0.05 on 1678 genes (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995). We obtained 1678 genes with corrected p-values between 0.00165 and 0.04998.

Fig. 2.

Analyses of data from microarray. (A) The box plot of gene expression Flight and Ground control groups. (B) Principal component analysis of Flight and Ground treatments. (C) Volcano plot of Flight sample transcript levels that are significantly different from Ground control samples. Dark dots represent genes that have >1.5 fold-change (x-axis) as well as high statistical significance cut off with a p-value < 0.05 (y-axis). The gray dots represent genes that are not significantly different.

The data sets that were uploaded into Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) 9.0 software were: 1678 significant genes with corrected p values < 0.05 and fold changes > 1.5; 28,972 “all” genes from the Affymetrix array, and 137 genes which were related to cell growth and proliferation. All input data sets consisted of three data columns, “Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array probe ID, p-value, and Fold Change”. While running a “Core Analysis” to the dataset, the “Filters and General Settings” were set up for the analysis. “Direct” and “Indirect Relationships” were included as interactions and “endogenous chemicals (metabolites)” in the network analysis, all the data sources were selected, and “Mouse” as the species. The IPA result panel included: “Summary, Networks, Functions, Canonical Pathways, Lists, My Pathways, Molecules, Network Explorer, and Overlapping Networks”. We focused on “Networks, Functions, and Canonical Pathways”.

Microarray data and the sample-quality data are publicly accessible by creating an account and logging into www.bioinformatics.kumc.edu/mdms/login.php. Thereafter the “Share Data with Users/Groups” link may be used, followed by “Browse through the shares”. The raw data and analyzed data sets may be accessed using the “Bone Marrow Macrophage Array”.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated by Student’s t-test or by Chi-Square (χ2) test (Statmost, Detaxiom Software Inc, Los Angeles, CA). P-values of <0.05 were selected to indicate significance. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (Sd) of the replicate number.

3. Results

3.1. Cell growth studies

In previous work, we found that macrophage growth was enhanced by space flight. However, the flight conditions necessitated that the cells differentiated at less than optimal physiological temperatures (Armstrong et al., 1995b). To determine if temperature would impact macrophage growth or differentiation during the STS-126 space flight, we determined cell proliferation in two ways. Viable cell numbers were determined at day 17 in the FPA set that was kept in medium throughout the entire mission and total cell numbers were counted in FPAs that were fixed in formalin at day 14 (Fig. 1) of the STS-126 mission. When we counted cells kept in medium for the entire mission (nonpreserved), we found that we had more viable cells in the flight FPAs (3.0 ± 0.6 × 107; mean ± Sd; n = 7) compared to the ground (1.7 ± 0.4 × 107; mean ± Sd; n = 4; t-test; p < 0.01). We also found more cells in the formalin-fixed flight FPAs (5.3 ± 0.6 × 106; mean ± Sd; n = 28) compared to cell numbers in the FPAs of the ground controls (4.4 ± 0.6 × 106; mean ± Sd; n = 32; t-test; p < 0.01). Although we could not determine the viability of the fixed cells using the trypan blue exclusion test, the increase in cell number from the time the cells were fixed on day 14 to recovery on at day 17 (Fig. 1A), suggests that the cells were viable at the time of fixation. There also was a similar amount of RNA collected per cell from each of the treatment groups; 4.1 × 10−6 ng/cell. Therefore, the fixed-cell estimates appear to be accurate and there appears to be more cell proliferation of the differentiated macrophages in space than on the ground. Flight cell numbers increased an average of 5.7 fold and ground cell numbers increased an average of 3.9 fold from day 14 to day 17. We also measured glucose utilization by the cells in the unfixed FPAs. We found significantly less (p < 0.05, t-test) glucose usage by flight cells (121 ± 4 mg/dl) compared to cells grown on the ground (159 ± 3 mg/dl). These data suggest that the cells required less energy to proliferate more in space.

3.2. Assessment of macrophage phenotype after space flight

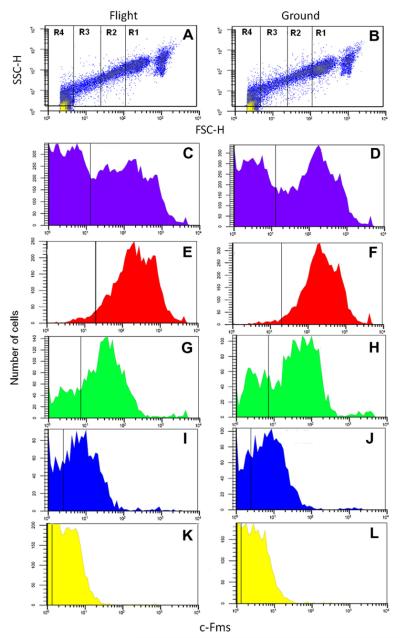

We found that there was a decrease in MHCII and Mac2 cell surface molecule expression on bone marrow cells differentiated into macrophages during space flight (Armstrong et al., 1995b). In those studies, cells were differentiated at temperatures ranging from 22.5 °C to 27.0 °C. We wanted to confirm that the space-flight differences were not due to the culture temperatures and we wanted to obtain a more comprehensive phenotypic analysis of the bone marrow-derived, M-CSF-dependent macrophages that emerged. We examined the phenotype of the cells using flow cytometry. We assigned 4 subpopulations of cells based on size (forward scatter, FSC-H) and granularity (side scatter, SSC-H) (Fig. 3A and B). Region (R) 1 identified the largest, most granular cells. R4 represented the smallest, least granular cells in the differentiated cell population. The macrophages in R1 and R2 had the highest expression level of c-Fms, and F4/80 macrophage markers compared to R3 and R4 (e.g. R1+R2 vs. R3+R4: c-Fms, 105.3% vs. 44.7%; F4/80, 6.4% vs. 0.1%;Table 1). Space flight did not affect these distributions (Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometric analysis of Flight (left column) and Ground control (right column) samples. (A and B) Representative plots of forward vs. side scatter to establish Regions 1–4 for further analysis. Histograms of total cells (C and D), Region 1 (E and F), Region 2 (G and H), Region 3 (I and J), Region 4 (K and L) for c-Fms expression.

Table 1.

Effect of spaceflight on M-CSF differentiated bone marrow-derived cell phenotypic markers.

| Cell marker | Subpopulation | Spaceflight | Ground control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ly6C* | Total cells | 5.8a | 9.2 |

| R1 | 20.0 | 24.7 | |

| R2 | 2.9 | 4.5 | |

| R3 | 0.5 | 7.1 | |

| R4 | 1.1 | 4.7 | |

| c-Fms | Total cells | 34.8 | 30.3 |

| R1 | 77.4 | 67.9 | |

| R2 | 56.2 | 37.4 | |

| R3 | 45.0 | 35.3 | |

| R4 | 10.5 | 9.4 | |

| CD11b* | Total cells | 0.1 | 6.7 |

| R1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | |

| R2 | 0 | 7.8 | |

| R3 | 0 | 57.3 | |

| R4 | 0 | 49.9 | |

| CD44 | Total cells | 45.4 | 45.7 |

| R1 | 62.7 | 67.0 | |

| R2 | 23.9 | 31.8 | |

| R3 | 16.3 | 16.8 | |

| R4 | 6.0 | 3.4 | |

| CD31 (PECAM) * | Total cells | 4.8 | 3.2 |

| R1 | 3.8 | 2.8 | |

| R2 | 14.2 | 4.1 | |

| R3 | 19.0 | 4.5 | |

| R4 | 13.3 | 15.1 | |

| Ly6G (Gr-1) | Total cells | 32.6 | 30.0 |

| R1 | 39.7 | 41.0 | |

| R2 | 11.5 | 8.4 | |

| R3 | 6.6 | 8.9 | |

| R4 | 4.3 | 8.4 | |

| CD3 | Total cells | 0.4 | 0 |

| R1 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| R2 | 2.2 | 0 | |

| R3 | 0.8 | 0 | |

| R4 | 1.5 | 0 | |

| F4/80* | Total cells | 5.0 | 2.7 |

| R1 | 11.6 | 3.7 | |

| R2 | 10.4 | 5.2 | |

| R3 | 1.4 | 0.1 | |

| R4 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| Mac2 * | Total cells | 5.5 | 4.5 |

| R1 | 8.5 | 0.5 | |

| R2 | 8.6 | 0 | |

| R3 | 6.2 | 0.4 | |

| R4 | 4.7 | 0.6 | |

| c-Fos * | Total cells | 2.5 | 3.3 |

| R1 | 3.7 | 4.0 | |

| R2 | 8.0 | 3.6 | |

| R3 | 10.6 | 0 | |

| R4 | 7.7 | 0 |

Numbers indicate % of cells above isotype control staining; 20,000 cells analyzed per sample. R1, region 1; R2, region 2; R3, region 3; R4, region 4.

Indicates flight sample is distributed differently from ground control as assessed by χ2 analysis.

When we compared the distribution of cells in R1-R4 between space flight samples and ground controls we had significant differences in the expression in Ly6C, CD11b, CD31, F4/80, Mac2 and c-Fos (p < 0.05, X2; Table 1). There was an overall decrease in Ly6C, CD11b, and c-Fos expression on cells differentiated in flight compared to those differentiated on the ground while there was an overall increase in CD31, F4/80 and Mac2 in flight cells compared to those differentiated on the ground (Table 1).

We anticipated that the developing cells would have a macrophage phenotype after 15 days because the bone marrow cells were differentiated in the presence of rmM-CSF (Metcalf, 1989). Therefore, we examined the cells for the concurrent expression of c-Fms and c-Fos with Mac2 and CD44, Ly6C and Ly6G (Gr-1) with F4/80 to help establish specific macrophage differentiation stages (Table 2). We found a significant increase in the overall expression of Mac2+c-Fms+ cells and Mac2+c-Fos+ cells differentiated in space compared to ground controls (p < 0.05) and a significant change in the distribution between the two treatment groups (p < 0.05, χ2 analysis; Table 2). However, we did not see a difference in the distribution of F4/80+CD44+ cells , F4/80+Ly6C+ cells or F4/80+Gr-1+ cells (Table 2) between space-flight samples and ground controls.

Table 2.

Effect of spaceflight on expression of double positive cell surface markers of differentiated bone marrow derived cells.

| Cell marker | Subpopulation a | Spaceflight b | Ground control b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mac2+, c-Fms+c | Total cells | 15.9 | 1.7 |

| R1 | 12.7 | 3.6 | |

| R2 | 27.0 | 0 | |

| R3 | 19.3 | 1.3 | |

| R4 | 12.3 | 1.3 | |

| Mac2+, c-Fos+c | Total cells | 6.8 | 0 |

| R1 | 8.4 | 0.1 | |

| R2 | 24.9 | 0 | |

| R3 | 13.4 | 0 | |

| R4 | 1.5 | 0 | |

| F4/80+, CD44+ | Total cells | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| R1 | 5.8 | 5.7 | |

| R2 | 3.8 | 0 | |

| R3 | 0.5 | 1.3 | |

| R4 | 0.7 | 0.1 | |

| F4/80+, Ly6C+ | Total cells | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| R1 | 0.4 | 5.0 | |

| R2 | 0.5 | 1.4 | |

| R3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | |

| R4 | 0.1 | 0.3 | |

| F4/80+, Gr1+ | Total cells | 0.5 | 0 |

| R1 | 0.8 | 3.2 | |

| R2 | 0.4 | 0.9 | |

| R3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| R4 | 0 | 0 |

Subpopulations established with forward vs. side scatter dot plots. R1, region 1; R2, region 2; R3 region 3; R4, region 4

Numbers indicate % cells above isotype control staining; 20,000 cells analyzed per sample.

Indicates flight sample is distributed differently from ground control as assessed by χ2 analysis.

3.3. Microarray analysis

To address possible mechanisms of how spaceflight affects macrophage proliferation and differentiation, we compared the transcriptional profile of bone marrow cells differentiated during space flight compared to cells differentiated on Earth. After 14 days of differentiation during space flight, the macrophages were preserved in GITC and RNA was hybridized to the Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 array as described in the Materials and Methods. We found that 607 genes had gene transcript levels >1.5 fold higher for flight samples than ground controls. In contrast, we found that 1071 genes had gene transcript levels >1.5 fold lower than ground controls (p < 0.05). The genes were sorted into biological function categories using IPA software (Table 3). These included genes involved in Carbohydrate metabolism, Cellular development, Hematopoiesis, Cellullar growth and proliferation, Lipid metabolism and many other functions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Biologic function classification of bone marrow derived macrophages gene regulation due to spaceflight.

| Biological function categoriesa | Lower p-valueb (×10−6) |

Upper p-valueb (×10−6) |

Number of genes |

Number of genes upregulatedc |

Number of genes downregulatedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory response | 0.34 | 46 300 | 100 | 32 | 68 |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | 46.8 | 44 300 | 44 | 6 | 38 |

| Molecular transport | 56.7 | 44 300 | 82 | 19 | 63 |

| Small molecule biochemistry | 56.7 | 44 300 | 102 | 21 | 81 |

| Cell death | 64.5 | 47 300 | 81 | 21 | 60 |

| Hematological system development and function |

87.9 | 47 700 | 118 | 38 | 80 |

| Hematopoiesis | 87.9 | 47 900 | 76 | 23 | 53 |

| Organismal development | 87.9 | 43 200 | 72 | 22 | 50 |

| Tissue development | 87.9 | 46 300 | 108 | 37 | 71 |

| Cellular compromise | 212 | 46 100 | 43 | 14 | 29 |

| Cardiovascular system development and function |

239 | 43 200 | 79 | 25 | 54 |

| Cellular development | 245 | 47 900 | 141 | 39 | 103 |

| Cellular growth and proliferation | 378 | 47 300 | 137 | 45 | 92 |

| Humoral immune response | 378 | 39 600 | 43 | 11 | 32 |

| Organismal survival | 385 | 7710 | 56 | 18 | 38 |

| Developmental disorder | 591 | 21 300 | 17 | 1 | 16 |

| Genetic disorder | 591 | 21 300 | 34 | 8 | 26 |

| Metabolic disease | 591 | 23 200 | 16 | 1 | 15 |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction | 654 | 46 100 | 60 | 17 | 43 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 671 | 28 000 | 20 | 6 | 14 |

| Inflammatory disease | 671 | 35 700 | 17 | 7 | 10 |

| Cellular movement | 701 | 47 700 | 96 | 27 | 69 |

| Immune cell trafficking | 701 | 47 700 | 65 | 18 | 47 |

| Embryonic development | 824 | 37 600 | 39 | 9 | 30 |

| Lipid metabolism | 824 | 44 300 | 72 | 12 | 60 |

| Cell cycle | 949 | 42 500 | 23 | 8 | 15 |

| Antimicrobial response | 959 | 21 400 | 12 | 3 | 9 |

| Hematological disease | 1170 | 34 800 | 32 | 11 | 21 |

| Organ development | 1240 | 39 600 | 46 | 14 | 32 |

| Cellular assembly and organization | 1410 | 42 500 | 66 | 22 | 44 |

| Cellular function and maintenance | 1410 | 47 800 | 95 | 25 | 70 |

| Tissue morphology | 1850 | 39 600 | 110 | 36 | 74 |

| Organismal injury and abnormalities | 2000 | 44 300 | 35 | 9 | 26 |

| Antigen presentation | 2260 | 46 300 | 36 | 9 | 27 |

| Cell-mediated immune response | 2260 | 21 800 | 24 | 6 | 18 |

| Lymphoid tissue structure and development | 2260 | 46 300 | 54 | 10 | 44 |

| Cell morphology | 3960 | 35 700 | 33 | 7 | 26 |

| Connective tissue development and function | 3960 | 39 600 | 41 | 10 | 31 |

| Connective tissue disorders | 3960 | 34 800 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Digestive system development and function | 3960 | 11 400 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Drug metabolism | 3960 | 34 800 | 9 | 2 | 7 |

| Endocrine system development and function | 3960 | 11 400 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Hepatic system development and function | 3960 | 11 400 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Hypersensitivity response | 3960 | 41 800 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Nervous system development and function | 3960 | 44 300 | 23 | 8 | 15 |

| Neurological disease | 3960 | 28 700 | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Nucleic acid metabolism | 3960 | 34 800 | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Organ morphology | 3960 | 44 300 | 40 | 10 | 30 |

| Skeletal and muscular disorders | 3960 | 21 800 | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| Skeletal and muscular system development and function |

3960 | 34 800 | 34 | 14 | 20 |

| Cancer | 4310 | 47 900 | 68 | 20 | 48 |

| Respiratory disease | 4770 | 44 300 | 12 | 4 | 8 |

| Visual system development and function | 5140 | 39 600 | 12 | 2 | 10 |

| Free radical scavenging | 7060 | 46 300 | 19 | 5 | 14 |

| Dermatological diseases and conditions | 7190 | 43 900 | 21 | 8 | 13 |

| Immunological disease | 7190 | 34 800 | 23 | 7 | 16 |

| Reproductive system development and function |

7780 | 44 300 | 18 | 7 | 11 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8570 | 47 900 | 33 | 8 | 25 |

| Endocrine system disorders | 9400 | 47 900 | 14 | 1 | 13 |

| Organismal functions | 10 000 | 32 900 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Hair and skin development and function | 11 400 | 11 400 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Hepatic system disease | 11 400 | 11 400 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Reproductive system disease | 11 400 | 28 000 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Infectious disease | 12 300 | 35 700 | 22 | 6 | 16 |

| Protein synthesis | 12 400 | 21 800 | 18 | 2 | 16 |

| Cell signaling | 15 700 | 33 500 | 10 | 1 | 9 |

| Amino acid metabolism | 21 400 | 33 700 | 11 | 4 | 7 |

| Gene expression | 21 500 | 21 500 | 54 | 24 | 30 |

| Auditory disease | 21 800 | 28 700 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Ophthalmic disease | 21 800 | 21 800 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Protein trafficking | 21 800 | 21 800 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Nutritional disease | 33 500 | 33 500 | 9 | 2 | 7 |

| Post-translational modification | 33 500 | 33 500 | 9 | 1 | 8 |

| Behavior | 33 700 | 33 700 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| DNA replication, recombination, and repair | 34 800 | 42 500 | 9 | 6 | 3 |

| Renal and urological system development and function |

34 800 | 34 800 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Vitamin and mineral metabolism | 34 800 | 34 800 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

Total number of unique genes with transcript levels at significantly higher concentration than ground control samples (FDR value at 0.05 and 1.5 fold change). The input for the IPA analysis was upregulated genes 607 and downregulated genes 1071 genes.

Gene expression data and IPA analysis was subjected to FDR (Benjamini-Holchberg) correction. P-value ranges reflect the chance genes have been randomly assigned to a specific biological function category using IPA software.

Genes may have been assigned to more than one category based on biological function classification. The unique upregulated genes were 130 and downregulated genes were 267 which were classified in the biological functional categories.

Since the cells were stimulated with rmM-CSF, we were particularly interested in transcriptional regulation of genes that are involved in cell division and development (Assigned to the Cell Death, Hematopoiesis, Cellular Development, Cellular Growth and Proliferation categories in Table 3). Using IPA software (www.ingenuity.com), we found 607 unique genes that had significantly higher transcript levels and 1071 unique genes that had significantly lower transcript levels during space flight compared to ground controls within the Cell Death, Cellular Growth and Proliferation, Cellular Development and Hematopoiesis subsets (Table 3). These genes were further classified based on gene ontology (GO) annotations (Supplement 1). In particular, the genes with down regulated transcripts encoded enzymes (Lfng, LFNG O-fucosylpeptide 3-beta-N acetylglucosaminyltransferase; Lipe, lipase, hormone-sensitive; Mettl8, methyltransferase like 8; and Adcy7 adenylate cyclase 7), growth factors (Pgf, placental growth factor; Igf1, insulin-like growth factor 1 (somatomedin C); Angpt1, angiopoietin 1; and Nrg2, neuregulin 2), Transcription factor binding (Meox2, mesenchyme homeobox 2; Mylb1, v-myb myeloblastosis viral oncogene homolog (avian)-like 1; Nab1, NGFI-A binding protein 1 or EGR1 binding protein 1). The genes that had significantly up regulated transcripts encoded cytokines (Ccl5; chemokine ligand 5), enzymes (Ido1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1; Nlgn1, neuroligin 1; Hs6st2, heparin sulfate 6-O-sulfotransferase 2); G-protein coupled receptors (Agtr1b, angiotensin II receptor; Bdkrb2, bradykinin receptor B2) transporters (Slc7a5, soute carrier family 7; Hba-a1, hemoglobin, alpha 1, Lrp2, low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 2). Molecules assigned to “other” molecule function were further classified according to MGI GO assignments (Supplement 1).

Analysis of the effect of space flight on the M-CSF signaling pathway revealed that gene transcripts encoding for the proteins Csf1r, Etv3, Fos, Rbl-1, Gata1, Gata2, Myc, Runx1, and E2f4 were downregulated greater than 1.5 fold in cells grown in space compared to ground controls. Alternatively, gene transcripts encoding proteins Egr1, Hoxb4 and Myb were higher in cells grown in space compared to cells maintained on Earth (Table 4). However, there were only significant differences (p < 0.05) in transcripts fold change for the genes Csf1r, E2f4, Rbl1, Egr1, Hoxb4, Gata2, Myc and Runx1.

Table 4.

M-CSF pathway of bone marrow derived macrophages gene regulation due to spaceflight.

| Gene symbol | Entrez gene ID | Gene name | p-Valuea | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Csf1r | 12978 | Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor | 0.04* | −1.6 |

| Hras1 | 15461 | Harvey rat sarcoma virus oncogene 1 | 0.24 | −1.3 |

| Ets1 | 23871 | E26 avian leukemia oncogene 1,5′ domain | 0.59 | 1.3 |

| Ets2 | 23872 | E26 avian leukemia oncogene 2,3′ domain | 0.79 | 1.1 |

| Etv3 | 27049 | ETS-domain transcriptional repressor, METS, Pe1 | 0.32 | −2.0 |

| Ddx20 | 53975 | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 20, Dp103. | 0.83 | −1.1 |

| Jun | 16476 | Jun oncogene | 0.62 | 1.3 |

| Fos | 14281 | FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene | 0.14 | −1.9 |

| Sin3 | 20467 | Transcriptional regulator, SIN3B (yeast) | 0.89 | −1.0 |

| Hdac2 | 15182 | Histone deacetylase 2 | 0.92 | 1.0 |

| Ncord2 | 20602 | Nuclear receptor co-repressor 2 | 0.37 | −1.2 |

| E2f4 | 104394 | E2F transcription factor 4 | 0.04* | −1.6 |

| Rbl-1 | 19650 | Retinoblastoma-like 1 (p107) | 0.02* | -4.4 |

| Rbl-2 | 19651 | Retinoblastoma-like 2 | 0.35 | −1.4 |

| Hoxb7 | 15415 | Homeobox B7 | 0.08 | 1.1 |

| Egr1 | 13653 | Early growth response 1 | 0.03 | 2.1 |

| Irf1 | 16362 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 | 0.79 | −1.0 |

| Chrac1 | 93696 | Chromatin accessibility complex 1 | 0.50 | −1.1 |

| Hoxb4 | 15412 | Homeobox B4 | 0.01 | 1.7 |

| Hoxb3 | 15410 | homeobox B3 | 0.03 | 1.2 |

| Cebpa | 12606 | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), alpha | 0.10 | −1.0 |

| Cebpb | 12608 | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta | 0.09 | 1.1 |

| Cebpg | 12611 | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), gamma | 0.69 | −1.1 |

| Gata1 | 14460 | GATA binding protein 1 | 0.37 | −1.5 |

| Gata2 | 14461 | GATA binding protein 2 | 0.04* | −2.1 |

| Scly | 50880 | Selenocysteine lyase | 0.38 | 1.1 |

| Myb | 17863 | Myeloblastosis oncogene | 0.19 | 1.8 |

| Myc | 17869 | Myelocytomatosis oncogene | 0.05 | −1.7 |

| Runx1 | 12394 | Runt re1ated transcription factor 1 | 0.04* | −1.6 |

| Tnf | 21926 | Tumor necrosis factor | 0.66 | −1.1 |

| Stat3 | 20848 | signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 | 0.64 | −1.1 |

| Sfpi1 | 20375 | SFFV proviral integration 1 | 0.56 | 1.1 |

| Zbtb16 | 235320 | Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16 | 0.21 | 1.2 |

Gene expression data and IPA analysis was subjected to FDR (Benjamini–Holchberg) correction with a cut-off value at 0.05.

Indicates genes below the cut off.

We also classified the gene microarray data into global canonical pathways and we selected pathways which were associated with genes whose transcription was significantly affected by the space flight. Canonical pathways were ranked based on the –log(p value) scores (p < 0.05). We found that the coagulation system (Table 5), Fc-gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and growth hormone signaling were pathways containing genes which had transcript levels that were significantly lower in flight samples compared to ground controls (1.5 fold change, p < 0.05; Supplement 2). The coagulation system had the highest – log(p value) score of any canonical pathway in this analysis. There were 6 genes which had significantly lower transcript levels in spaceflight samples compared to ground controls (p < 0.05; Table 5). In addition, 8 genes showed a trend where transcript levels were lower than ground controls even though they were not statistically different. The insulin receptor signaling pathway also had a high –log(p value) score amongst canonical signaling pathways identified by the IPA analysis. Six genes had significantly lower transcript levels in comparison to ground controls (p < 0.05;Table 6). When we examined other signaling pathways that are relevant to macrophage function (Oda et al., 2004; Raza et al., 2008), we found that several other macrophage signaling pathways also had genes that had lower transcript levels in space flight samples compared to ground controls (p < 0.05). These included Fcc receptor mediated phagocytosis in macrophages and monocytes, mTOR, CCR5 signaling, p38 map kinase, and FLT3 signaling in hematopoietic progenitor cells (Supplement 2).

Table 5.

Transcriptional changes in coagulation system components.

| Fold change | p-Valuea | Coagulation components and regulatorsb |

|---|---|---|

| −1.1 | NS | Factor II, Prothrombin: C |

| −1.8 | 0.04 | Factor III, Thromboplastin (Tissue Factor): E |

| 1.8 | NS | Factor V, Labile factor (accelerator globulin, accelerin): C |

| −1.9 | NS | Factor VII, Serum (or tissue) prothrombin: E |

| −2.5 | NS | Factor VIII, Anti-hemophilic factor A: I |

| −2.7 | 0.04 | Factor IX, Christmas factor: |

| −1.5 | NS | Factor X, Stuart Power factor: C |

| 1.5 | NS | Factor XI, Plasma thromboplastin antecedent (PTA): I |

| −4.6 | NS | Factor XII, Hageman factor (contact factor): I |

| −1.8 | NS | Factor XIII, Fibrin-stabilizing factor: C |

| −2.9 | NS | Protein C: I and C |

| −2.3 | 0.04 | Protein S: I and C |

| −2.1 | NS | Thrombomodulin: I and C |

| −5.0 | 0.04 | Kallekrein B1: I |

| −2.4 | 0.04 | Tissue factor pathway inhibitor: E |

| −6.5 | 0.04 | Plasmin: F |

| −1.5 | NS | Von Willebrand factor: I and E |

| −1.5 | NS | Plasminogen activator, urokinase: F |

Gene expression data and IPA analysis was subjected to FDR (Benjamini–Holchberg) correction. No significant difference (NS), FDR value at 0.05.

Components involved in intrinsic (I), extrinsic (E), or common (C) coagulation pathways or in fibrinolysis (F).

Table 6.

Insulin receptor signaling pathway of bone marrow derived macrophages gene regulation due to spaceflight.

| Gene symbol | Entrez gene ID | Gene name | p-Valuea | Fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insr | 16337 | Insulin receptor | 0.044* | −2.01 |

| Cbl | 12402 | Casitas B-lineage lymphoma | 0.008* | −1.90 |

| Rhoq | 104215 | Ras homolog gene family, member Q | 0.008 | −1.35 |

| Tsc2 | 22084 | tuberous sclerosis 2 | 0.044* | −2.50 |

| Rapgef1 | 107746 | Rap guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 1 | 0.045* | −1.61 |

| Pten | 19211 | Phosphatase and tensin homolog | 0.045* | −1.83 |

| Lipe | 16890 | Lipase, hormone sensitive | 0.041* | −3.61 |

| Nck1 | 17973 | Non-catalytic region of tyrosine kinase adaptor protein 1 | 0.048* | −1.70 |

| Gab1 | 14388 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 2-associated protein 1 | 0.048* | −2.53 |

| Ptpn11 | 19247 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11 | 0.076 | −1.44 |

| Foxo4 | 54601 | Forkhead box O4 | 0.101 | −3.22 |

| Sgk1 | 20393 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 | 0.127 | −1.99 |

| Socs3 | 12702 | Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | 0.138 | 2.41 |

| Stx4a | 20909 | Syntaxin 4A (placental) | 0.139 | 1.09 |

| Mtor | 56717 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin (serine/threonine kinase) | 0.155 | −1.31 |

| Rptor | 74370 | Regulatory associated protein of MTOR, complex 1 | 0.174 | −1.66 |

| Eif4ebp1 | 13685 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 | 0.185 | −1.25 |

| Raf1 | 110157 | v-Raf-leukemia viral oncogene 1 | 0.191 | 1.67 |

| Irs1 | 16367 | Insulin receptor substrate 1 | 0.198 | −1.55 |

| Mapk8 | 26419 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 8 | 0.257 | −1.47 |

| Ptpn1 | 19246 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 1 | 0.289 | −1.26 |

| Foxo3 | 56484 | Forkhead box O3 | 0.298 | 1.28 |

| Ptprf | 19268 | Protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, F | 0.340 | 2.08 |

| Pde3b | 18576 | Phosphodiesterase 3B, cGMP-inhibited | 0.357 | 1.32 |

| Stxbp4 | 20913 | Syntaxin binding protein 4 | 0.409 | −1.59 |

| Slc2a4 | 20528 | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 4 | 0.445 | 1.81 |

| Vamp2 | 22318 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 | 0.450 | 1.24 |

| Tsc1 | 64930 | Tuberous sclerosis 1 | 0.461 | −1.43 |

| Pdpk1 | 18607 | 3-Phosphoinositide dependent protein kinase 1 | 0.520 | −1.30 |

| Eif4e | 13684 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E | 0.555 | −1.33 |

| Bad | 12015 | BCL2-associated agonist of cell death | 0.558 | 1.20 |

| Grb2 | 14784 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 2 | 0.672 | −1.10 |

| Fyn | 14360 | Fyn proto-oncogene | 0.704 | −1.13 |

| Shcl | 20416 | Src homology 2 domain-containing transforming protein C1 | 0.756 | 1.15 |

| Acly | 104112 | ATP citrate lyase | 0.889 | −1.04 |

| Grb10 | 14783 | Growth factor receptor bound protein 10 | 0.917 | −1.08 |

| Trip10 | 106628 | Thyroid hormone receptor interactor 10 | 0.960 | 1.02 |

| Akt1 | 11651 | Thymoma viral proto-oncogene 1 | 0.432 | −1.64 |

| Mapk1 | 26413 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 | 0.422 | −1.65 |

| Foxo1 | 56458 | Forkhead box O1 | 0.381 | −1.15 |

| Gsk3b | 56637 | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | 0.105 | −1.57 |

| Gys1 | 14936 | Glycogen synthase 1, muscle | 0.834 | 1.13 |

| Irs1 | 16367 | Insulin receptor substrate 1 | 0.198 | −1.54 |

| Jak1 | 16451 | Janus kinase 1 | 0.075 | −1.62 |

| Map2k1 | 26395 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 | 0.236 | −1.75 |

| Rps6kb1 | 72508 | Ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 1 | 0.220 | −1.72 |

| Pik3r1 | 18708 | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, regulatory subunit, polypeptide 1 (p85 alpha) | 0.051 | −1.84 |

| Prkaca | 18747 | Protein kinase, cAMP dependent, catalytic, alpha | 0.657 | 1.05 |

| Prkcz | 18762 | Protein kinase C, zeta | 0.772 | −1.22 |

| Ppp1cc | 19047 | Protein phosphatase 1, catalytic subunit, gamma isoform | 0.096 | −1.15 |

| Rasa1 | 218397 | RAS p21 protein activator 1 | 0.239 | −1.57 |

| Inpp5d | 16331 | Inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase D | 0.149 | −1.27 |

| Kcnj8 | 16523 | Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 8 | 0.298 | 1.36 |

Gene expression data and IPA analysis were subjected to FDR (Benjamini–Holchberg) correction.

Indicates genes below the 0.05 cut off.

4. Discussion

We reexamined the impact of space flight on macrophage growth and development during the space flight of STS-126 to test whether changes in the expression of the receptor for M-CSF were affected by space flight. We found that bone marrow-derived macrophages proliferated faster during space flight compared to ground controls to reaffirm previous findings (Armstrong et al., 1995b) even though there were significant temperature differences between these experiments and those older experiments. The data also support observations that show that bacteria (Benoit and Klaus, 2007), plant (Matia et al., 2010) and mammalian cells (Slentz et al., 2001; Tobin et al., 2001) grow faster in space or clinorotation. The increased proliferation was not associated with a concomitant increase in glucose use to mediate that growth and supports the hypothesis that cells do not have to work as hard to grow in space. However, not all cell types respond in this same manner during space flight. Osteoblasts grew less and used less glucose than comparable ground controls on STS-56 (Hughes-Fulford and Lewis, 1996) and U937 cells depleted glucose rapidly when grown in space hardware (Hatton et al., 1999). Therefore, glucose utilization during growth may be cell-type specific.

Our primary hypothesis was that the changes in growth and differentiation during space flight were due to decreased expression of the receptor for M-CSF (c-Fms); the growth factor used to induce the differentiation of macrophages from bone marrow stem cells. We found that the transcript level of Csfr was lower in space flight samples compared to ground controls. However, when we examined the level of c-Fms molecules on the surface of the cells by flow cytometry, we found an increase in the receptor. This conundrum could be explained by increased protein translation efficiency during space flight. Factors such as protein concentration affect translational efficiency (Morgan et al., 1971), and the lack of convection in space could affect local concentrations of M-CSF as well as other cytokines. Signal transduction can also be altered by space flight (Akiyama et al., 1999; Cogoli, 1997; De Groot et al., 1991, Hatton, Gaubert, 1999, Nickerson et al., 2000; Schwarzenberg, 1999) and the efficiency of protein synthesis can be altered by cytokines and growth factors and their coordinating pathways (Hornberger and Esser, 2004). However, Etheridge et al. found that the components that control the RNAi process that regulate translation and the inhibitory effects of RNAi were unaffected by space flight (Etheridge et al., 2011). Therefore, questioning the efficiency of translation may not be appropriate. Alternatively, the discrepancy between the transcript level and protein level could have resulted from when we measured these processes. Csfr transcripts are stabilized during macrophage differentiation (Stone et al., 1990) and c-Fms plasma membrane levels are generally stable and dependent on the concentration of M-CSF present (Rettenmier et al., 1987). Therefore, the macrophages in our space culture FPAs may have had more c-Fms molecules present because there was less rmM-CSF remaining in those FPAs. Unfortunately, we did not assay for M-CSF in the cultures from this experiment. We found very low levels of all the cytokines we did perform assays for (GM-CSF, IL-1, TNF, IL-6, data not shown). By 15 days of culture, the supernatants were generally devoid of labile cytokines. We also did not have enough RNA left over after the gene array to validate the Csfr transcript concentrations. We note, however, that Runx1 transcript levels were also significantly lower in the space-flown cells. There is a strong correlation in expression between Csfr and Runx1, (Himes et al., 2005) which helps to increase our confidence in these data. Nevertheless, additional work will be needed to resolve this issue.

The increased number Mac2+c-Fms+ cells and the generally increased expression of F4/80 on the macrophages differentiated in space suggests that there is a more differentiated population of cells present after space flight. F4/80 (Caminschi et al., 2001; Hume et al., 2002) and Mac2 (Dong and Hughes, 1997; Ho and Springer, 1982) are macrophage-specific markers that tend to increase as macrophages mature (Leenen et al., 1990, 1994). A decrease in Ly6C in the total, R1 and R2 populations in the cells we identified would also support this conclusion since Ly6C identifies myeloid cells at an intermediate stages of differentiation (Leenen et al., 1994). However, other data related to the differentiation state of the macrophages in our space cultures were not consistent with this conclusion. We did not see a decrease in the Ly6G or CD31 expression on the macrophages flown in space. Ly6G is expressed on macrophages early in differentiation, granulocytes and other cells (Ammon et al., 2000; Ferret-Bernard et al., 2004; Leenen et al., 1990) and CD31 is expressed on macrophages early in differentiation and decreases as they mature (de Bruijn et al., 1994; de Bruijn et al., 1998; Watt et al., 1993). We also did not see an increase in CD11b or in the F4/80+Ly6C− or the F4/80+Ly6G− populations. These latter two populations should have increased as macrophages became more differentiated. Therefore, it might be more appropriate to say that the macrophages that develop in space are different from those that develop on the Earth even though we can not necessarily characterize them as more or less differentiated from each other. This conclusion would not contradict data from STS-57, STS-60 and STS-62 (Armstrong et al., 1995b). Moreover, when we assessed the relative levels of transcripts of transcription factors (Sfpi1, Egr1, Myc, Stat3, Tnf, Hoxb7, Cebpb, Runx1, Chrac1, Egr1, Irf1, Jun, and Fos) that are necessary for the differentiation of M-CFU into macrophages (Valledor et al., 1998), we found that most of these were not significantly up or down regulated (>1.5 fold) in the space-flight samples compared to ground controls. This suggests that space flight was not affecting the differentiation of the macrophages.

There were significant changes in transcript levels of 1678 genes in macrophages that develop in space compared to those that develop on Earth. These data suggest that space flight has an effect on M-CSF-stimulated macrophages in vitro. The array of gene transcripts that were altered suggests that there were global impacts on the cells; not just on specific molecular signaling pathways. Nevertheless, when we examined pathways particularly relevant to bone marrow macrophage growth and differentiation, i.e. the M-CSF signaling pathway, there were transcript changes that were consistent with increased cellular proliferation. For example, the down regulation of Rbl-1 (encodes p107) in the M-CSF pathway in the flight cells is consistent with the increased proliferation of myeloid cells in p107 knockout mice (LeCouter et al., 1998). Similarly, the significant down regulation of E2f4 would also be consistent with increased proliferation. E2f4 regulates the cell cycle and inhibits cell proliferation (Attwooll et al., 2004). Mutations in E2f4 lead to hematological cancers (Komatsu et al., 2000) because of its role in regulating cell fate (Enos et al., 2008). Furthermore, if one examines the transcript levels of transcription factors that are activated during the differentiation of stem cells into M-CFU macrophage progenitors (Valledor, Borras, 1998), only Hoxb3 and Hoxb4 were up regulated and only Hoxb4 was significant (>1.5 fold increase; p < 0.05). Hoxb3 and Hoxb4 are necessary for myeloid cell proliferation (Bjornsson et al., 2003; Sauvageau et al., 1997) but are not needed for lineage commitment (Bjornsson et al., 2003). In contrast, two of the three transcription factors that are significantly down regulated during early macrophage differentiation in space flight samples (Gata2 and Runx1) are either not needed for macrophage terminal differentiation (Gata2) (Tsai and Orkin, 1997) or serve as an inhibitor of proliferation (Runx1) (Himes et al., 2005). Interestingly, Myc was also down regulated and macrophage proliferation is also driven by c-Myc protein (Wickstrom et al., 1988; Yu et al., 2005). This inconsistency might be because c-Myc is needed early in macrophage proliferative response during differentiation (Valledor et al., 1998) and we were already 15 days into the differentiation process. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that transcripts of other key inducers of proliferation such as cyclophilin A (Ppia) and cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk2) also trended lower in space-flight samples (Ppia, −1.11 fold change; Cdk2, −1.26 fold change) and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (Cdkn1a), an inhibitor of cellular proliferation trended with higher transcript levels in space-flight cells (Cdkn2a, −1.32 fold change). It appears that the proliferative phase was in the process of changing by the 15th day of culture.

The most interesting revelation of the IPA analysis of the transcriptional array of bone marrow macrophage differentiation in space was the broad impact of space flight on the coagulation pathway. Sixteen genes were down regulated in toto. Genes encoding proteins involved in both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways were affected; indicating a broad impact. Kimzey et al. suggested that there may be a “hypercoagulative condition” after the flight of the Skylab astronauts (Kimzey et al., 1975b). However, after closer examination of the data from Skylab missions (Kimzey, 1977; Kimzey et al., 1975a, 1975b, 1976), it appears that this hypothesis was based on observations of platelets and not coagulation-pathway proteins. If there are alterations in the ability of space travelers to coagulate blood, this could have ramifications on astronaut recovery from injury from bleeding, angiogenesis and inflammation. For example, fragments of plasminogen (encoded by Plg), which had significantly lower transcript concentrations in flight samples compared to ground controls, inhibit angiogenesis (O’Reilly et al., 1994) and are involved in regulating macrophage migration (Gong et al., 2008). Additional examination of these systems in vivo is justified.

5. Conclusion

We have confirmed that space flight has a significant impact on murine bone marrow macrophages in vitro. We see significant increases in cell proliferation and changes in the pattern of expression of cell-surface differentiation antigens. Differences in gene expression in 1678 genes in the differentiating macrophages during space flight are consistent with this observation. Importantly, these changes do not appear to be from decreases in the surface expression of the receptor for M-CSF. We recently found that there are changes in bone marrow subpopulations in mice after they are subjected to space flight (Ortega et al., 2009). The data from STS-126 indicates that there can also be direct gravitational effects on those bone marrow cells. The long-term effects of these changes have yet to be determined and should be the focus of appropriate studies on the International Space Station.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Alison Fedrow, Dr. Lea Dib, and Mr. Alejandro Estrada for their help in setting up these experiments at Kansas State University. We thank Dr. Louis Stodiek and the BioServe team at the University of Colorado and Dr. Kevin Sato of NASA Ames for their help in executing these experiments. This project has been supported by NASA grant NNX08BA91G, American Heart Association grant 0950036G, NIH grants AI55052, AI052206, AI088070, RR16475 and RR17686, the Terry C. Johnson Center for Basic Cancer Research and the Kansas Agriculture Experiment Station.

We thank the Kansas University Medical Center-Microarray Facility (KUMC-MF) for generating array data sets. The Microarray Facility is supported by the Kansas University-School of Medicine, KUMC Biotechnology Support Facility, the Smith Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center (HD02528), and the Kansas IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence (RR016475). This is Kansas Agriculture Experiment Station publication 12-034-J.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.asr.2012.02. 021.

References

- Akiyama H, Kanai S, Hirano M, et al. Expression of PDGF-beta receptor, EGF receptor, and receptor adaptor protein Shc in rat osteoblasts during spaceflight. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 1999;202:63–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1007097511914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammon C, Meyer SP, Schwarzfischer L, Krause SW, Andreesen R, Kreutz M. Comparative analysis of integrin expression on monocyte-derived macrophages and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Immunology. 2000;100:364–369. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00056.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JA, Balch S, Chapes SK. Interleukin-2 therapy reverses some immunosuppressive effects of skeletal unloading. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994;77:584–589. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JA, Kirby-Dobbels K, Chapes SK. The effects of rM-CSF and rIL-6 therapy on immunosuppressed antiorthostatically suspended mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 1995a;78:968–975. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.3.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JA, Nelson K, Simske S, Luttges M, Iandolo JJ, Chapes SK. Skeletal unloading causes organ specific changes in immune cell responses. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993;75:2734–2739. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong JW, Gerren RA, Chapes SK. The effect of space and parabolic flight on macrophage hematopoiesis and function. Experimental cell research. 1995b;216:160–168. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwooll C, Denchi EL, Helin K. The E2F family: specific functions and overlapping interests. The EMBO journal. 2004;23:4709–4716. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqai FP, Gridley DS, Slater JM, et al. Effects of spaceflight on innate immune function and antioxidant gene expression. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1935–1942. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91361.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Royal Statistical Soc. Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit MR, Klaus DM. Microgravity, bacteria, and the influence of motility. Advances in Space Research. 2007;39:1225–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson JM, Larsson N, Brun ACM, et al. Reduced Proliferative Capacity of Hematopoietic Stem Cells Deficient in Hoxb3 and Hoxb4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:3872–3883. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3872-3883.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caminschi I, Lucas KM, O’Keeffe MA, et al. Molecular cloning of F4/80-like-receptor, a seven-span membrane protein expressed differentially by dendritic cell and monocyte-macrophage subpopulations. J Immunol. 2001;167:3570–3576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.7.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapes SK. Lessons from Immune 1–3: what did we learn and what do we need to do in the future? J Gravit Physiol. 2004;11:P45–P48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapes SK, Mastro A, Sonnenfeld G, Berry W. Antiorthostatic suspension as a model for the effects of spaceflight on the immune system. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1993;54:227–235. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles D. The Highs and Lows of Shuttle Science. Science. 2011;333:30–33. doi: 10.1126/science.333.6038.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogoli A. Signal transduction in T lymphocytes in microgravity. Gravitational and Space Biology Bulletin. 1997;10:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn MF, Slieker WA, van der Loo JC, Voerman JS, van Ewijk W, Leenen PJ. Distinct mouse bone marrow macrophage precursors identified by differential expression of ER-MP12 and ER-MP20 antigens. European journal of immunology. 1994;24:2279–2284. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn MF, van Vianen W, Ploemacher RE, et al. Bone marrow cellular composition in Listeria monocytogenes infected mice detected using ER-MP12 and ER-MP20 antibodies: a flow cytometric alternative to differential counting. J. Immunol. Methods. 1998;217:27–39. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot R, Rijken P, Den Hertog J, et al. Nuclear responses to protein kinase C signal transduction are sensitive to gravity changes. Exp. Cell Res. 1991;197:87–90. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90483-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Hughes RC. Macrophage surface glycoproteins binding to galectin-3 (Mac-2-antigen) Glycoconjugate journal. 1997;14:267–274. doi: 10.1023/a:1018554124545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudoit S, Yang YH, Callow MJ, Speed TP. Statisticl methods for identifying differentially expressed genes in replicated cDNA microarray experiments. Statistica Sinica. 2002;12:111–139. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Johnson P, Lange R. Hematopoiesis in antiorthostatic, hypokinesic rats. The Physiologist. 1983;26:S133–4. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Johnson P, Lange R, Perez L, Nessel R. Regulation of hematopoiesis in rats exposed to antiorthostatic, hypokinetic/hypodynamia: I. Model description. Aviat. Space and Environ. Med. 1985;56:419–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enos ME, Bancos SA, Bushnell T, Crispe IN. E2F4 Modulates Differentiation and Gene Expression in Hematopoietic Progenitor Cells during Commitment to the Lymphoid Lineage. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;180:3699–3707. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etheridge T, Nemoto K, Hashizume T, et al. The Effectiveness of RNAi in Caenorhabditis elegans Is Maintained during Spaceflight. PloS one. 2011;6:e20459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagette S, Somody L, Bouzeghrane F, et al. Biochemical characteristics of beta-adrenoceptors in rats after an 18-day spaceflight (LMS-STS78) Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 1999;70:1025–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferret-Bernard S, Sai P, Bach JM. In vitro induction of inhibitory macrophage differentiation by granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, stem cell factor and interferon-gamma from lineage phenotypes-negative c-kit-positive murine hematopoietic progenitor cells. Immunol. Lett. 2004;91:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Hart E, Shchurin A, Hoover-Plow J. Inflammatory macrophage migration requires MMP-9 activation by plasminogen in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:3012–3024. doi: 10.1172/JCI32750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gridley DS, Slater JM, Luo-Owen X, et al. Spaceflight effects on T lymphocyte distribution, function and gene expression. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:194–202. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91126.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris SA, Zhang M, Kidder LS, Evans GL, Spelsberg TC, Turner RT. Effects of orbital spaceflight on human osteoblastic cell physiology and gene expression. Bone. 2000;26:325–331. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(00)00234-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton JP, Gaubert F, Lewis ML, et al. The kinetics of translocation and cellular quantity of protein kinase C in human leukocytes are modified during spaceflight. The FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 1999;13(Suppl):S23–S33. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.9001.s23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes SR, Cronau S, Mulford C, Hume DA. The Runx1 transcription factor controls CSF-1-dependent and -independent growth and survival of macrophages. Oncogene. 2005;24:5278–5286. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MK, Springer TA. Mac-2, a novel 32,000 Mr mouse macrophage subpopulation-specific antigen defined by monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 1982;128:1221–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn A, Klaus DM, Stodieck LS. A modular suite of hardware enabling spaceflight cell culture research. J Gravit Physiol. 2004;11:39–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger TA, Esser KA. Mechanotransduction and the regulation of protein synthesis in skeletal muscle. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2004;63:331–335. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Fulford M, Lewis ML. Effects of microgravity on osteoblast growth activation. Experimental cell research. 1996;224:103–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume DA, Ross IL, Himes SR, Sasmono RT, Wells CA, Ravasi T. The mononuclear phagocyte system revisited. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2002;72:621–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiki A, Gibson L, Jago T, et al. Effects of spaceflight on rat peripheral blood leukocytes and bone marrow progenitor cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;60:37–43. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur I, Simons ER, Castro VA, Ott CM, Pierson DL. Changes in monocyte functions of astronauts. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2005;19:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimzey S. In: Hematology and immunology studies. Johnston RS, Dietlin LF, editors. NASA SP-377, National Aeronauticsand Space Administration; Washington D.C.: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kimzey S, Fischer C, Johnson P, Ritzmann S, Mengel C. In: Hematology and immunology studies. Johnston RS, Dietlin LF, Berry CA, editors. NASA SP-368.National Aeronautics and Space Administration; Washington, D.C.: 1975a. [Google Scholar]

- Kimzey SL, Johnson PC, Ritzman SE, Mengel CE. Hematology and immunology studies: the second manned Skylab mission. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 1976;47:383–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimzey SL, Ritzmann SE, Mengel CE, Fischer CL. Skylab experiment results: hematology studies. Acta astronautica. 1975b;2:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0094-5765(75)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Takeuchi S, Ikezoe T, et al. Mutations of the E2F4 gene in hematological malignancies having microsatellite instability. Blood. 2000;95:1509–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeCouter JE, Kablar B, Hardy WR, et al. Strain-Dependent Myeloid Hyperplasia, Growth Deficiency, and Accelerated Cell Cycle in Mice Lacking the Rb-Related p107 Gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7455–7465. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenen PJ, de Bruijn MF, Voerman JS, Campbell PA, Van Ewijk W. Markers of mouse macrophage development detected by monoclonal antibodies. J. Immunol. Methods. 1994;174:5–19. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leenen PJ, Melis M, Slieker WA, Van Ewijk W. Murine macrophage precursor characterization. II. Monoclonal antibodies against macrophage precursor antigens. European journal of immunology. 1990;20:27–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttges MW. Recognizing and optimizing flight opportunities with hardware and life sciences limitations. Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 1992;95:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matia I, Gonzalez-Camacho F, Herranz R, et al. Plant cell proliferation and growth are altered by microgravity conditions in spaceflight. Journal of plant physiology. 2010;167:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan R, Neale L, Kraus E, et al. Alteration in human mononuclear leucocytes following space flight. Immunol. 1992;76:491–497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf D. The molecular contol of cell division, differentiation commitmant and maturation in haemopoietic cells. Nature. 1989;339:27–30. doi: 10.1038/339027a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey-Holton ER, Globus RK. Hindlimb unloading of growing rats: a model for predicting skeletal changes during space flight. Bone. 1998;22:83S–88S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey-Holton ER, Globus RK. Hindlimb unloading rodent model: Technical aspects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;92:1367–1377. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00969.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan HE, Jefferson LS, Wolpert EB, Rannels DE. Regulation of Protein Synthesis in Heart Muscle. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1971;246:2163–2170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson CA, Ott CM, Mister SJ, Morrow BJ, Burns-Keliher L, Pierson DL. Microgravity as a novel environmental signal affecting Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium virulence. Infection and immunity. 2000;68:3147–3152. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3147-3152.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly MS, Holmgren L, Shing Y, et al. Angiostatin: a novel angiogenesis inhibitor that mediates the suppression of metastases by a Lewis lung carcinoma. Cell. 1994;79:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda K, Kimura T, Matsuoka Y, Funahashi A, Muramatsu M, Kitano H. Molecular Interaction Map of a Macrophage. AfCS, Research Reports. 2004;2 [Google Scholar]

- Ortega MT, Pecaut MJ, Gridley DS, Stodieck LS, Ferguson VL, Chapes SK. Shifts in Bone Marrow Cell Phenotypes Caused by Space Flight. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:548–555. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91138.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecaut MJ, Nelson GA, Peters LL, et al. Genetic models in applied physiology: Selected contribution: Effects of spaceflight on immunity in the C57BL/6 mouse. I. Immune population distributions. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003;94:2085–2094. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01052.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BE, Hart ML, Snyder LL, Boyle D, Mosier DA, Chapes SK. Differentiation of C2D macrophage cells after adoptive transfer. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:243–252. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00328-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza S, Robertson K, Lacaze P, et al. A logic-based diagram of signalling pathways central to macrophage activation. BMC Systems Biology. 2008;2:36. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-2-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettenmier CW, Roussel MF, Ashmun RA, Ralph P, Price K, Sherr CJ. Synthesis of membrane-bound colony-stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and downmodulation of CSF-1 receptors in NIH 3T3 cellstransformed by cotransfection of the human CSF-1 and c-fms (CSF-1 receptor) genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1987;7:2378–2387. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.7.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronca AE, Alberts JR. Physiology of a microgravity environment selected contribution: effects of spaceflight during pregnancy on labor and birth at 1 G. J Appl Physiol. 89:849–54. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.849. discussion 8, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvageau G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Hough MR, et al. Overexpression of HOXB3 in hematopoietic cells causes defective lymphoid development and progressive myeloproliferation. Immunity. 1997;6:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzenberg M. Signal Transduction In T Lymphocytes – A Comparison of the Data From Space, the Free Fall Machine and the Random Positioning Machine. Adv. Space Res. 1999;24:793–798. doi: 10.1016/s0273-1177(99)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slentz DH, Truskey GA, Kraus WE. Effects of chronic exposure to simulated microgravity on skeletal muscle cell proliferation and differentiation. In vitro cellular & developmental biology. 2001;37:148–156. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2001)037<0148:EOCETS>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld G, Mandel A, Konstantinova I, et al. Space flight alters immune cell function and distribution. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992;73:191S–195S. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.2.S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenfeld G, Mandel AD, Konstantinova IV, et al. Effects of spaceflight on levels and activity of immune cells. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 1990;61:648–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R, Imamura K, Datta R, Sherman M, Kufe D. Inhibition of phorbol ester-induced monocytic differentiation and c-fms gene expression by dexamethasone: potential involvement of arachidonic acid metabolites. Blood. 1990;76:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe RP, Sams CF, Pierson DL. Effects of mission duration on neuroimmune responses in astronauts. Aviation, space, and environmental medicine. 2003;74:1281–1284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suda T. Lessons from the space experiment SL-J/FMPT/L7: the effect of microgravity on chicken embryogenesis and bone formation. Bone. 1998;22:73S–78S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G, Neale L, Dardano J. Immunological analyses of U. S. Space Shuttle crew members. Aviat Space Envir Md. 1986;57:213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin BW, Leeper-Woodford SK, Hashemi BB, Smith SM, Sams CF. Altered TNF-a, glucose, insulin, and amino acids in islets of Langerhans cultured in a microgravity model system. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2001;280:E92–E102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.1.E92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd P. Gravity-dependent phenomena at the scale of the single cell. ASGSB Bulletin. 1989;2:95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai FY, Orkin SH. Transcription factor GATA-2 is required for proliferation/survival of early hematopoietic cells and mast cell formation, but not for erythroid and myeloid terminal differentiation. Blood. 1997;89:3636–3643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacek A, Bartonickov A, Rotkovsk D, Michurina T, Damaratskaya E, Serova L. The effects of weightlessness and increased gravity on hemopoietic stem cells of rats and mice. The Physiologist. 1983;26:S131–S132. [Google Scholar]

- Valledor AF, Borras FE, Cullell-Young M, Celada A. Transcription factors that regulate monocyte/macrophage differentiation. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:405–417. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt SM, Williamson J, Genevier H, et al. The heparin binding PECAM-1 adhesion molecule is expressed by CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells with early myeloid and B-lymphoid cell phenotypes. Blood. 1993;82:2649–2663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom EL, Bacon TA, Gonzalez A, Freeman DL, Lyman GH, Wickstrom E. Human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cell proliferation and c-myc protein expression are inhibited by an antisense pentadecadeoxynucleotide targeted against c-myc mRNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1988;85:1028–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JW, Ott CM, Zu Bentrup KH, et al. Space flight alters bacterial gene expression and virulence and reveals a role for global regulator Hfq. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:16299–16304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707155104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods KM, Chapes SK. Abrogation of TNF-mediated cytotoxicity by space flight involves protein kinase-C. Exp. Cell Res. 1994;211:171–174. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, et al. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: a robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.4.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu RY, Wang X, Pixley FJ, et al. BCL-6 negatively regulates macrophage proliferation by suppressing autocrine IL-6 production. Blood. 2005;105:1777–1784. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.