Abstract

Conventional asymmetric PCR is inefficient and difficult to optimize because limiting the concentration of one primer lowers its melting temperature below the reaction annealing temperature. Linear-After-The-Exponential (LATE)–PCR describes a new paradigm for primer design that renders assays as efficient as symmetric PCR assays, regardless of primer ratio. LATE-PCR generates single-stranded products with predictable kinetics for many cycles beyond the exponential phase. LATE-PCR also introduces new probe design criteria that uncouple hybridization probe detection from primer annealing and extension, increase probe reliability, improve allele discrimination, and increase signal strength by 80–250% relative to symmetric PCR. These improvements in PCR are particularly useful for real-time quantitative analysis of target numbers in small samples. LATE-PCR is adaptable to high throughput applications in fields such as clinical diagnostics, biodefense, forensics, and DNA sequencing. We showcase LATE-PCR via amplification of the cystic fibrosis CFΔ508 allele and the Tay-Sachs disease TSD 1278 allele from single heterozygous cells.

Crucial decisions in preimplantation genetic diagnosis, infectious diseases, bioterrorism, forensics, and cancer research increasingly depend on detection of specific DNA targets, even down to alleles of single-copy genes in single cells (1, 2). Conventional real-time PCR permits rapid and quantitative identification of unique DNA targets, but reactions typically slow down and plateau stochastically because reannealing of the template strands gradually outcompetes primer and probe binding to the template strands (3, 4).

Asymmetric PCR potentially circumvents the problem of amplicon strand reannealing by using unequal primer concentrations (5). Depletion of the limiting primer during the exponential amplification results in the linear synthesis of the strand extended from the excess primer. Although asymmetric PCR generates brighter signals than symmetric PCR does (6), it is seldom used because it exhibits overall efficiencies of 60–70%, in contrast to symmetric PCR, which is typically 90% or more efficient (7, 8). Asymmetric PCR also requires extensive optimization to identify the proper primer ratios, the amounts of starting material, and the number of amplification cycles that can generate reasonable amounts of product for individual template-target combinations.

This article describes a rational strategy for designing efficient, sensitive, and versatile asymmetric amplification reactions. We call this method LATE-PCR, for Linear-After-The-Exponential–PCR. LATE-PCR implements innovations in primer design based on the primer-target hybridization equilibriums that govern amplification reactions. As a result, LATE-PCR exhibits similar efficiency to symmetric PCR while promoting accumulation of single-stranded products with predictable kinetics for many cycles beyond the exponential phase, enabling the use of primers over a wide range of concentration ratios, improving signal strength by 80–250%, and permitting routine quantitative detection of even single molecules. LATE-PCR also introduces innovations in thermal cycling that uncouple primer annealing from probe detection and reduce the constraints on the design of allele-discriminating probes.

We showcase the principles and benefits of this new method of PCR through analysis of two disease-causing single-copy genes in single lymphoblasts. Tay-Sachs disease (TSD) is a lethal neurodegenerative disorder of early childhood caused by mutations in the α-subunit of the β-N-acetylhexosaminidase (HEXA) gene (9). Approximately 79% of Ashkenazi Jews who are carriers contain an insertion of 4 nucleotides (GATC) in HEXA exon 11 (TSD 1278 HEXA allele; ref. 10). Cystic fibrosis (CF) is caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene that encodes a chloride channel (11). Approximately 70% of the CF mutations among Caucasians are caused by a 3-bp deletion that removes a phenyl-alanine at position 508 of the protein (the CFTR ΔF508 allele).

Materials and Methods

Cells. Lymphoblasts heterozygous for the TSD 1278 HEXA and the CFΔ508 alleles were from the Coriell Cell Repositories (Camden, NJ; cell lines GM11852 and GM08337) and were prepared for single-cell PCR as described (12, 13).

Molecular Beacons. The TSD 1278 HEXA high-melting temperature (Tm) molecular beacon has been described (4). The TSD 1278 HEXA and the CFΔ508 low-Tm molecular beacons were 5′FAM-CGCGACGTATATCTATCCTATGGCTCGCG-Dabcyl 3′ and 5′ TET-CGCGCTAAAATATCATTGGTGTTTCCTAAGCGCG-Dabcyl 3′. Allele discrimination was tested by using the TSD 1421 low-Tm and high-Tm molecular beacons 5′FAM-CGTGCGCTCTGGTAAGGGTTTGCACG-Dabcyl 3′ and 5′FAM-GCGACGGCTCTGGTAAGGGTTTTCGGCGTCGC-Dabcyl 3′ against their matched and 1-bp mismatched targets 5′-TCCCCCCCGAAAACCCTTACCAGAGCCTGGGG-3′ and 5′-TCCCCCCCGAAAACCCTTAGCAGAGCCTGGGG-3′. Molecular beacons and oligonucleotide targets and primers were purchased from Research Genetics (Huntsville, AL) and Biosearch Technologies (Novato, CA). Melting curves for allele discrimination were done according to the method of Tyagi and Kramer (14) by using 3 mM MgCl2.

In the case of molecular beacons, low-Tm probes have Tm 5°C or more below the limiting primer Tm in the asymmetric reaction (i.e., have shorter loops, typically <20 nucleotides, and shorter stems, typically 5–6 base pairs, compared with high-Tm probes that typically have loops of >20 nucleotides and stems of 6–7 base pairs). Molecular beacon Tm was measured empirically from melting curves.

Primers and Tm Calculations. Table 1 shows the TSD 1278 HEXA primer sequences. The excess CFΔ508 primer used in Fig. 2 was 5′-CTTTGATGACGCTTCTGTATCTA-3′, and the limiting CFΔ508 primers were 5′-GATTATGCCTGGCACCAT-3′, 5′-GGATTATGCCTGGCACCAT-3′, or 5′-CCTGGATTATGCCTGGCACCAT-3′ to achieve (TmL – TmX) values of –3.0, –1.4, and 4.0, respectively (added nucleotides are underlined). TmL and TmX stand for the melting temperatures of the limiting primer and the excess primer, respectively. Product specificity was confirmed as reported (4). The primer concentration-adjusted Tm was based on the nearest-neighbor formula (15) by using 70 nM and half the primer concentration as inputs for monovalent cation and primer concentrations, respectively (16). This formula underestimates primer Tm in Mg2+-containing PCR buffers but provides valuable comparisons for designing amplification reactions.

Table 1. TSD 1278 HEXA primers.

| Method | Primer | Sequence | Concentration, nM | Tm*, °C | ΔTm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symmetric PCR | TSD1 | 5′-CCTTCTCTCTGCCCCCTGGT-3′ | 1,000 | 64.8 | 0 |

| TSD2 | 5′-GCCAGGGGTTCCACTACGTAGA-3′ | 1,000 | 64.3 | ||

| Conventional asymmetric PCR | TSD1 | 5′-CCTTCTCTCTGCCCCCTGGT-3′ | 25 | 58.9 | -5 |

| TSD2 | 5′-GCCAGGGGTTCCACTACGTAGA-3′ | 1,000 | 64.3 | ||

| LATE-PCR† | Modified TD1 | 5′-GCCCTTCTCTCTGCCCCCTGGT-3′ | 25 | 64.0 | 0

|

| TSD2 | 5′-GCCAGGGGTTCCACTACGTAGA-3′ | 1,000 | 64.3 |

Concentration-adjusted Tm calculated according to the nearest-neighbor formula.

Nucleotides underlined and in bold were added to match Tm values.

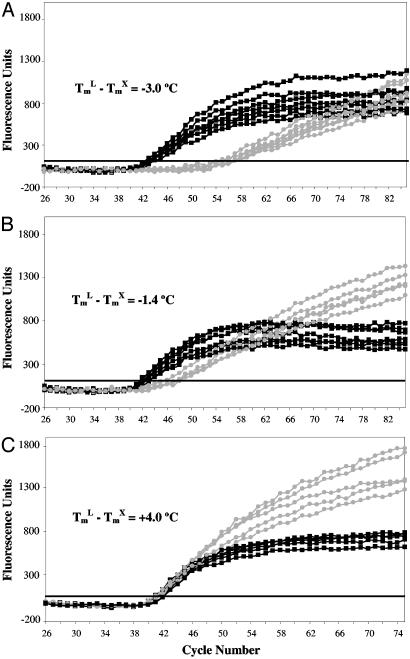

Fig. 2.

Comparison of symmetric and asymmetric reactions using CFΔ508 primers pairs differing in (TmL – TmX) values. Increases in (TmL – TmX) values increase amplification efficiency. Conventional asymmetric PCR primers (TmL – TmX) < 0 (A) yield inefficient amplification relative to symmetric control (1:1 primer ratio). Only primers fitting the LATE-PCR criterion (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0ata 1:10 ratio (C) yield amplification efficiencies (CT values) comparable to symmetric control.  , Asymmetric reactions; ▪, symmetric reactions.

, Asymmetric reactions; ▪, symmetric reactions.

LATE-PCR adjusts the sequence and/or length of the 5′ end of the limiting primer such that (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0. The excess primer concentration was 1,000 nM to promote efficient linear amplification, whereas the limiting primer concentration was set to 25–50 nM to generate a linear kinetic plot once the primer ran out at the threshold cycle (CT).

PCR Conditions. Single-cell samples were manipulated and prepared for PCR as described (12, 13). For the TSD 1278 HEXA primers, thermal cycling consisted of 95°C for 3 min; followed by 10 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 60°C for 10 sec, and 72°C for 20 sec; then 70 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 20 sec. and 72°C for 20 sec. LATE-PCR includes a postextension detection step at 45°C for 20 sec beginning at cycle 10. Detection of high-Tm and low-Tm molecular beacons was done during the 55°C step and the 45°C step, respectively. For the CFΔ508 primers, thermal cycling consisted of 95°C for 5 min; followed by 4 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 30 sec; then 21 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 55°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec; followed by 60 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 52°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec, with fluorescence acquisition at 52°C. Contamination control procedures for reagent preparation and sample handling were as described (12).

Results

The Logic of LATE-PCR. Conventional symmetric PCR uses equimolar concentrations of two primers with similar Tm. We discovered that traditional asymmetric PCR assays are inefficient and unpredictable, because they are designed by using symmetric primers, without taking into account the effect of the actual primer concentrations on primer Tm. Primer Tm is sometimes calculated by using the “%GC” (17) or the “2 (A+T) plus 4 (G+C)” (18) methods, which do not consider primer concentration. Alternatively, primer Tm is calculated by using a nearest-neighbor formula that includes a term for primer concentration (19) and thus is amenable to using actual, as opposed to nominal, concentrations. When symmetric PCR primers are used for asymmetric reactions, the nearest-neighbor formula reveals that the Tm of the limiting primer, TmL, is often several degrees below the Tm of excess primer, TmX: (TmL – TmX) < 0. Under these conditions, asymmetric reactions are inefficient (see below). LATE-PCR corrects this problem by adjusting the length and nucleotide composition of the excess and the limiting primers to ensure that (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0, based on concentration-adjusted Tm values (Table 1). The resulting LATE-PCR assays can be as efficient as symmetric PCR and have additional advantages.

In real-time symmetric PCR, product detection depends on probe-target hybridization during the annealing step, when the target strand is transiently single-stranded. The probe Tm must be higher than the primer Tm (20) to guarantee that it hybridizes to the target strand before the primer extends beyond its binding site (20). In contrast, LATE-PCR generates single-stranded amplicons and permits uncoupling of primer annealing from product detection. As a result, the Tm of the probe no longer needs to be higher than the Tm of either primer. Low-Tm probes are inherently more allele-discriminating, generate lower background, and can be used at saturating concentrations without interfering with the efficiency of amplification.

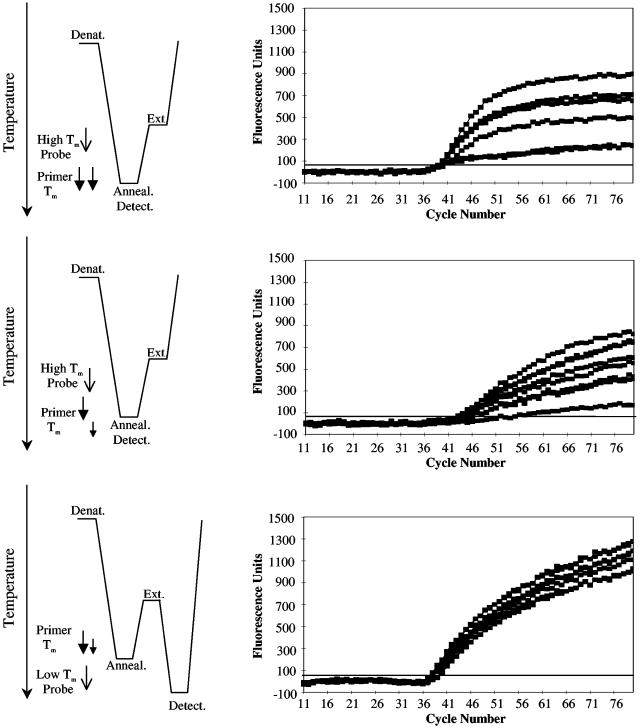

Comparison of Symmetric PCR, Conventional Asymmetric PCR, and LATE-PCR. Fig. 1 compares fully optimized symmetric, asymmetric, and LATE-PCR assays initiated from single cells heterozygous for the TSD 1278 HEXA allele. The symmetric reactions used equimolar concentrations of primers with similar Tm (see Table 1) and were monitored with a hybridization probe against the mutant allele having a probe Tm above the primer Tm (hereafter referred to as a “high-Tm” probe; Fig. 1 A). The mean CT of these reactions was 39.7 ± 1.2. The CT is the thermal cycle at which the signal first exceeds the fluorescence detection threshold (21). Signal accumulation in symmetric reactions plateaued at approximately cycle 50 and exhibited relatively low and variable fluorescence levels with a mean value of 632 ± 275 at cycle 80, F80 value (Fig. 1 A). Asymmetric PCR assays using the same primers at a 1:40 ratio did not plateau even after 80 cycles but reached detection 5.5 cycles later (mean CT, 45.2 ± 1.3) and had a signal strength (mean F80, 602 ± 280) similar to the symmetric reactions (Fig. 1B). Table 1 shows that the reduced concentration of the limiting primer lowers its Tm and generates a value for (TmL – TmX) = –5°C.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of symmetric PCR (A), standard asymmetric PCR (B), and LATE-PCR (C). (Left) The thermal profile and relative primer and hybridization probe Tm for different amplification methods. Arrow size and length reflect differences in primer concentration, and the lower tip of each arrow indicates the melting temperature, Tm, of each primer. Symmetric (A) and conventional asymmetric (B) PCR use hybridization probes whose loop Tm is above the primer Tm but below the extension temperature (high-Tm probes). LATE-PCR (C) introduces low-Tm probes whose loop Tm is 5°C to 10°C below TmL of the limiting primer, and a low-temperature detection step either before or after the extension temperature. (Right) The amplification kinetics of replicate reactions for different amplification methods. Symmetric PCR (A) plateaus around cycle 50 and exhibits highly variable kinetics with a large end-point range. In contrast, conventional asymmetric PCR (B) exhibits delayed linear kinetics and low end-point signals. Only LATE-PCR (C) exhibits efficient linear kinetics for >80 cycles.

In contrast, LATE-PCR assays had a mean CT of 39 ± 0.8, similar to that of symmetric PCR (Fig. 1C). The fluorescent signal continued to increase linearly and reached a mean value of 1,180 ± 102 at F80, 87% higher than that of the symmetric reactions. These improvements in amplification efficiency and signal strength were achieved by adjusting the length of the limiting primer such that (TmL – TmX) = 0°C at the same 1:40 ratio (Table 1) and by using a “low-Tm” probe that hybridized at a separate detection step introduced into the thermal profile after the extension step. The independent contributions of these improvements in primer design and probe design to the efficiency and sensitivity of LATE-PCR assays are described in detail below.

Validation of LATE-PCR Primer Design. LATE-PCR assays become more efficient as the Tm of the limiting primer increases relative to the Tm of the excess primer: (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0. Fig. 2 illustrates this point for three pairs of CF gene primers whose (TmL – TmX values range from –3°C to 4°C. As (TmL – TmX) approaches and then exceeds 0, the mean CT value of these three sets of assays decreases, and LATE-PCR assays become as efficient as symmetric PCR. The mean F75 values of the resulting signals also increase by 81% to 116% relative to the symmetric assays.

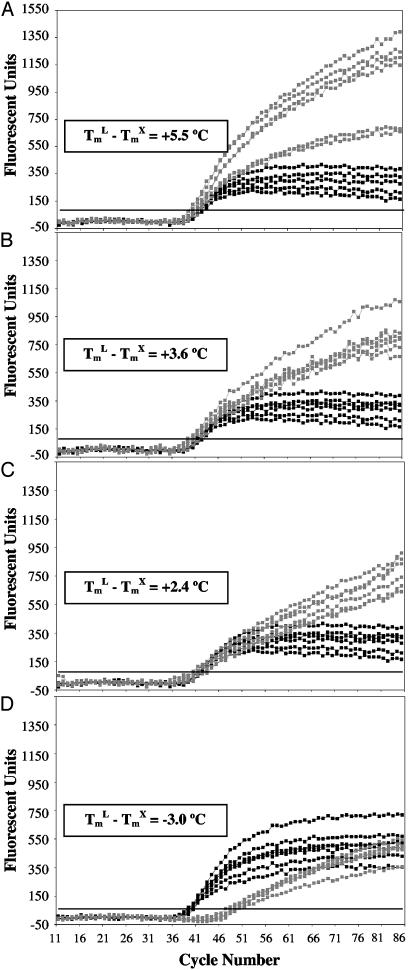

LATE-PCR Provides Greater Flexibility in the Design and Use of Primers. Judged from their CT values, LATE-PCR assays over a wide range of primer ratios are just as efficient as symmetric PCR assays when (TmL – TmX) is ≥0 (Fig. 3 A–C). In contrast, asymmetric reactions using symmetric PCR primers at a ratio of 1:100 were inefficient and exhibit delayed CT values because (TmL – TmX) < 0 (Fig. 3D). Thus, LATE-PCR makes it easier to design pairs of primers that support efficient amplification regardless of the ratios at which they are used.

Fig. 3.

Flexible use of primer ratios in LATE-PCR. LATE-PCR primers at 1:10 (A), 1:40 (B), and 1:100 (C) ratios wherein (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0 have similar amplification efficiencies. In contrast, conventional symmetric PCR primers at a 1:100 ratio (D), wherein (TmL – TmX) < 0 are inefficient. Primer ratios were created by holding the concentration of the excess primer constant and then decreasing the concentration of the limiting primer.  , Asymmetric reactions; ▪, symmetric reactions.

, Asymmetric reactions; ▪, symmetric reactions.

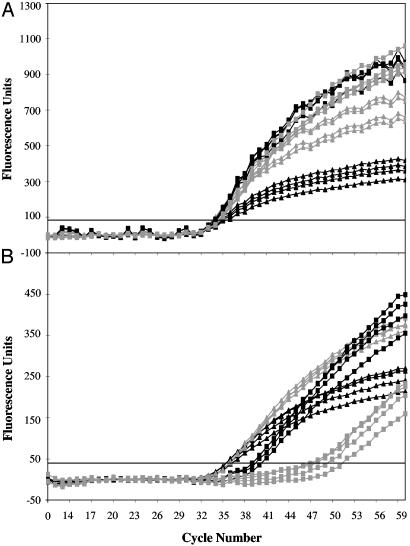

LATE-PCR also Allows Greater Flexibility in the Use of Probes. Low-Tm probes allow unimpeded annealing and extension of the limiting primer on the excess primer strand during exponential amplification phase and therefore can be used at concentrations high enough to saturate all accumulated single-stranded products (2–4 μM) without altering reaction kinetics, provided that the concentration-dependent probe Tm remains below the limiting primer Tm. These properties of low-Tm probes are demonstrated in Fig. 4A. At both 2.4 μM and 4.0 μM probe concentrations, the fluorescent signal reached a level 250% above that of the 0.6 μM probe concentration. In contrast, Fig. 4B shows that increasing the concentration of a high-Tm probe to 2.4 μM delayed detection of a signal by 3.6 cycles, and increasing it to 4.0 μM delayed the signal by 13.5 cycles.

Fig. 4.

Saturating low-Tm probe concentrations increase sensitivity without affecting amplification efficiency. Low-Tm molecular beacons (A) and high-Tm molecular beacons (B) were used at increasing concentrations of 0.6 μM (▴), 1.2 μM (▵), 2.4 μM (▪), or 4.0 μM (□) for amplicon detection. Low-Tm probes maintain the CT values and display maximum sensitivity at saturating concentrations. In contrast, increasing the concentration of the high-Tm probes delays CT values and decreases sensitivity.

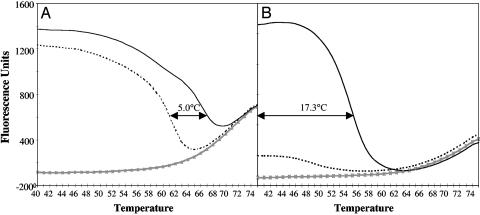

Low-Tm probes also have greater allele-discriminating capacity than high-Tm probes do. This feature stems from the fact that the length of the low-Tm probe-target hybrid is shorter, and thus a single base pair mismatch has a greater destabilizing effect (22–24). Fig. 5 compares melting profiles of high-Tm and low-Tm probes to perfectly matched and mismatched targets. In the case of the high-Tm probe, the window of discrimination is 5°C (Fig. 5A), whereas the low-Tm probe has a window of discrimination of at least 17°C (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Low-Tm molecular beacons improve allele discrimination over a wider range of detection temperatures compared with high-Tm probes. Melting curves of high-Tm (A) and low-Tm (B) molecular beacons specific for the wild-type TSD 1421 HEXA allele bound to various targets illustrate the increased allele-discrimination capacity of low-Tm molecular beacons. -×-×-, No target; ———, correct target; ······, 1-nt mismatched target. Arrows indicate the temperature discrimination window between matched and mismatched targets.

Discussion

LATE-PCR provides a rational approach to generating single-stranded DNA products based on knowledge of the primer-target hybridization equilibriums that drive asymmetric reactions. As a result, LATE-PCR exhibits similar efficiency to symmetric PCR and enables the use of primers over a wide range of concentration ratios. These improvements are made possible by adjusting the length and nucleotide composition of the limiting and excess primer to assure that (TmL – TmX) ≥ 0. Additional benefits are achieved by modifying the thermal cycles to uncouple primer annealing and product detection, which in turn permits the use of low-Tm probes that improve allele discrimination and increase signal strength severalfold.

Under LATE-PCR conditions, the initial exponential phase of the reaction generates double-stranded amplicons until the limiting primer concentration falls abruptly and the reaction switches to synthesis of only excess primer strands. In the case of real-time LATE-PCR, the amount of limiting primer is deliberately chosen such that the exponential phase of the reaction switches to the linear phase shortly after the reaction reaches detectability, i.e., the CT value. LATE-PCR therefore maintains the quantitative nature of real-time symmetric PCR assays, which is based on the CT values of the exponential phase of the reaction. Upon switching, the number of excess primer strands accumulated per cycle is proportional to the number of limiting primer strands present at the time of the switch. The subsequent linear phase of the reaction also proceeds efficiently because the relationship between TmX and the Tm of the amplicon strands, TmA, is adjusted to maximize the yield of single-stranded products in the reaction. Optimal single-strand synthesis occurs when (TmA – TmX) ≈ 13°C (data not shown).

In LATE-PCR, detection of accumulating excess primer strand is best accomplished with a nonhydrolyzable probe that targets this strand. Probes that target the limiting primer strand and are hydrolyzed by TaqDNA polymerase during extension of the excess primer (25) are not well suited for LATE-PCR, because reannealing of the limiting primer strand to the accumulating excess primer strands tends to outcompete hybridization of the probe. In addition, hydrolyzable probes must have a higher Tm than that of the primers (25) and therefore cannot take advantage of the low-Tm probe format.

LATE-PCR makes it possible to introduce a detection step distinct from the annealing step. The temperature of the detection, therefore, can be lowered to permit the use of low-Tm probes having greater allele-discrimination capacity and improved signal-to-noise ratios. Because the Tm of a low-Tm probe is well below the extension temperature of the reaction, saturating concentrations (2–4 μM) can be used to detect all of the single-stranded molecules produced. These advances improve signal strength severalfold compared with conventional probes used in symmetric and asymmetric reactions. In light of these changes, conventional probes can now be regarded as high-Tm probes.

LATE-PCR realizes the goals historically envisioned for asymmetric PCR by Gyllensten and Erlich (5). By eliminating the need for mechanical (26) or enzymatic separation and purification of single-stranded DNA (27), or the use of a separate linear amplification step (28), LATE-PCR is ideally suited for use as a prelude to DNA sequencing. In addition, the closed-tube format makes LATE-PCR amenable to automated recovery of product strands for use as probes for microarrays, single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis (SSCP) (29), single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) screening (30), and digital PCR (31).

Acknowledgments

This work was partially funded by Hamilton-Thorne Biosciences. We also gratefully acknowledge funding from Brandeis University for this research.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: LATE-PCR, Linear-After-The-Exponential–PCR; TSD, Tay-Sachs disease; CF, cystic fibrosis; HEXA, β-N-acetylhexosaminidase; Tm, melting temperature; TmL, limiting primer Tm; TmX, excess primer Tm; CT, threshold cycle.

References

- 1.Hahn, S., Zhong, X. Y., Troeger, C., Burgemeister, R., Gloning, K. & Holzgreve W. (2000) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57, 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, H. H., Gyllensten, U. B., Cui, X. F., Saiki, R. K., Erlich, H. A. & Arnheim, N. (1988) Nature 335, 414–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd, K. K. & Ruano, G. (1995) in PCR 2: A Practical Approach, ed. McPherson, M. J. (IRL, Oxford), pp. 1–21.

- 4.Rice, J. E., Sanchez, J. A., Pierce, K. E. & Wangh, L. J. (2002) Prenatal Diagn. 22, 1130–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gyllensten, U. B. & Erlich, H. A. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 7652–7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poddar, S. K. (2000) Mol. Cell. Probes 14, 25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCabe, P. C. (1999) in PCR Protocol: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds. Innis, M. A., Gelfand, D. H., Sninsky, J. J. & White, T. J. (Academic, New York), pp. 76–83.

- 8.Gyllensten, U. B. & Allen, M. (1993) Methods Enzymol. 218, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risch, N. (2001) Adv. Genet. 44, 233–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Triggs-Raine, B., Mahuran, D. J. & Gravel, R. A. (2001) Adv. Genet. 44, 199–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welsh, M. J., Tsui, L. P., Boat, T. F. & Beaudet, A. L. (1995) in The Metabolic and Molecular Basis of Inherited Disease, eds. Scriver, C. R., Beaudet, A. L., Sly, W. S. & Valle, D. (McGraw–Hill, New York), Vol. III, pp. 3799–3876. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce, K. E., Rice, J. E., Sanchez, J. A., Brenner, C. & Wangh, L. J. (2000) Mol. Hum. Reprod. 6, 1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce, K. E., Rice, J. E., Sanchez, J. A. & Wangh, L. J. (2002) Biotechniques 32, 1106–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tyagi, S. & Kramer, F. R. (1996) Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allawi, H. T. & SantaLucia, J. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 10581–10594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Novère, N. (2001) Bioinformatics 17, 1226–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howley, P. M., Israel, M. A., Law, M. F. & Martin, M. A. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 4876–4883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace, R. B., Shaffer, J., Murphy, R. F., Bonner, J., Hirose, T. & Itakura, K. (1979) Nucleic Acids Res. 10, 3543–3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SantaLucia, J. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay, I. M., Arden, K. E. & Nitsche, A. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1292–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higuchi, R., Fockler, C., Dollinger, G. & Watson, R. (1993) Biotechnology 11, 1026–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aboul-ela, F., Koh, D., Tinoco, I., Jr., & Martin, F. H. (1985) Nucleic Acids Res. 13, 4811–4824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tyagi, S., Bratu, D. P. & Kramer, F. R. (1998) Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afonina, I. A., Reed, M. W., Lusby, E., Shishkina, I. G. & Belousov, Y. S. (2002) Biotechniques 32, 940–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heid, C. A., Stevens, J., Livak, K. J. & Williams, P. M. (1996) Genome Res. 6, 986–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hultman, T., Stahl, S., Hornes, E. & Uhlén, M. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 4937–4946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higuchi, R. G. & Ochman, H. (1989) Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medori, R., Tritschler, H. J. & Gambetti, P. (1992) Biotechniques 12, 346–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi, K. (1991) PCR Methods Appl. 1, 34–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marras, S. A., Kramer, F. R. & Tyagi, S. (2003) Methods Mol. Biol. 212, 111–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vogelstein, B. & Kinzler, K. W. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9236–9241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]