Abstract

The POU domain transcription factors Oct-1 and Oct-2 interact with the octamer element, a motif conserved within Ig promoters and enhancers, and mediate transcription from the Ig loci. Inactivation of Oct-2 by gene targeting results in normal B cell development and Ig transcription. To study the role of Oct-1 in these processes, the lymphoid compartment of RAG-1–/– animals was reconstituted with Oct-1-deficient fetal liver hematopoietic cells. Recipient mice develop B cells with levels of surface Ig expression comparable with wild type, although at slightly reduced numbers. These B cells transcribe Ig normally, respond to antigenic stimulation, undergo class switching, and use a normal repertoire of light chain variable segments. However, recipient mice show slight reductions in serum IgM and IgA. Thus, the Oct-1 protein is dispensable for B cell development and Ig transcription.

B cell development consists of an ordered program of transcriptional events, leading ultimately to the rearrangement and expression of Ig molecules (1). Although the Ig heavy and light chain enhancers contain binding sites for numerous different classes of transcription factors, variable region promoters seem to be less complex and prominently contain a motif termed the octamer element (5′-ATGCAAAT-3′) (2–6). The canonical octamer or its reverse complement is conserved in the majority of Ig heavy and light chain variable region promoters (7). This sequence is also present in the intronic and 3′ enhancers of the Ig heavy chain locus.

The importance of the octamer element in mediating Ig transcription has been demonstrated by using transgenic mice: a point mutation in the octamer reduces the expression of an Ig-transgene by over 20-fold (8). Several studies have indicated that, when attached to a heterologous promoter, the octamer element can confer B cell specificity (6, 9). Octamer or octamer-like sequences have been implicated in the regulation of a number of lymphoid-specific genes such as CD20, CD21, CD36, IL-2, IL-4, and Pax-5 (10–18). However, octamer elements are also important in the regulation of ubiquitously expressed genes such as U1, U2, and U6 small nuclear RNA and histone H2B (19–22).

The POU proteins Oct-1 and Oct-2 were identified as protein activities that selectively interact with the octamer sequence (22–28). The DNA-binding POU domain consists of two subdomains (the POU-specific and POU-homeodomain) tethered by a short linker sequence (29–31). The DNA-binding domains of Oct-1 and Oct-2 are highly homologous, and both proteins bind octamer DNA with equal affinity in vitro (32). Oct-1 is widely expressed whereas Oct-2 expression is restricted to the lymphoid and neuronal compartments (33, 34). Because of its expression pattern, Oct-2 was thought to be an important regulator of Ig expression. However, B cell development in Oct-2–/– animals is normal. Analysis of Oct-2–/– fetal liver revealed the presence of pre-B cells with rearranged Ig genes in numbers similar to that of wild-type littermates. The transcription rates of several genes, including Igμ and Igκ, were also normal in the fetal liver pre-B cells (35). Although early B cell development was largely unaffected, stimulation of Oct-2–/– splenic B cells with the T cell-independent polyclonal antigen lipopolysaccharide failed to induce proliferation, consistent with a defect in antigen-dependent terminal B cell development (35, 36). Adoptive transfer experiments also demonstrated a complete lack of peritoneal B-1 cells (37). These results have been corroborated by somatic gene targeting of Oct-2 in WEHI-231 cells, a mature B cell line expressing surface Ig. In this system, no change in the activity of either a transfected Ig promoter or a heterologous promoter containing an octamer element was detected. However, when concatemerized octamer elements were fused with a promoter to mimic enhancer activity, transcription was decreased in Oct-2–/– cells (38). Another study using altered specificity mutants indicated that Oct-2 acts at the 3′ enhancer of the IgH locus in mature B cells (39).

To explain the B cell specificity of the Ig locus, a model involving the interaction of Oct-1 and Oct-2 with tissue-specific coactivators was proposed. The discovery of OCA-B/Bob-1/OBF-1, a B cell-specific cofactor that interacts with both Oct-1 and Oct-2 (40–42), provided a possible explanation for the B cell-restricted activity of the octamer element. OCA-B is largely B cell restricted but can be induced in T cells with phorbol-esters and ionomycin (43). However, targeted disruption of OCA-B did not result in a significant perturbation in B cell development. OCA-B-deficient mice are viable and fertile and have normal B cell numbers in the bone marrow and slightly reduced B cell numbers in the spleen. They also display markedly reduced levels of secondary Ig isotypes, suggesting a defect in class switching. Most strikingly, these animals show a complete lack of germinal centers (44, 45). Even in the absence of both Oct-2 and OCA-B, B cells with normal levels of surface Ig can be generated (46).

Genetic studies using OCA-B and Oct-2 mutant mice suggest a model whereby Oct-1 plays a key role in mediating B cell specificity at the Ig locus either by compensating for Oct-2 in its absence or by conferring a unique role independently of Oct-2. To further investigate this hypothesis and to understand the determinants governing Oct-1 and Oct-2 functional specificity in vivo, we created a loss-of-function model for Oct-1 using gene targeting (47). Here, we demonstrate that functional B cells with normal levels of surface Ig can be generated in adoptive transfer experiments using Oct-1-deficient fetal liver cells, suggesting that Oct-1 alone is dispensable for B cell development but may function redundantly with Oct-2.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Mouse Strains and Adoptive Transfer. The generation of a mouse Oct-1 targeted allele has been described (47). Heterozygous mutant mice were mated with B1-8 transgenic animals (48, 49). Oct-1–/+;B1-8 transheterozygous offspring were intercrossed to generate homozygous mutants carrying the B1-8 transgene. Fetal livers were harvested from embryonic day 12.5 embryos and genotyped as described (48). PCR primers for genotyping Oct-1–/– have been reported, and the primers used for B1-8 are as follows: 5′-ACGATTACTACGGTAGTAGCTAC-3′ and 5′-GGAAACTAGAACTACTCAAGCTA-3′. The presence of the B1-8 transgene resulted in a 1.3-kb fragment. After genotyping, 5- to 8-week-old RAG-1–/– recipient animals were sublethally irradiated with 400 rad by using a 137Cs source. At least 1 × 106 fetal liver cells were retroorbitally injected in 250 μl of Hanks' buffered saline. Recipients were maintained in autoclaved cages on water containing trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. The lymphoid compartment of the recipients was analyzed 12–16 weeks after transfer.

Generation of Abelson-Transformed Lines and Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assays. Abelson-transformed cell lines were derived by infecting 2 × 106 bone marrow cells from adoptively transferred recipient mice with Abelson virus in the presence of 4 μg/ml polybrene. The cells were cultured as described (50). Nuclear extract was prepared according to ref. 51. The electrophoretic mobility shift assay was performed as described (47).

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) Analyses. Single cell suspensions from bone marrow and spleen were prepared according to standard procedures. Enucleated red blood cells were lysed with PharmLyse (Pharmingen) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were subsequently incubated with α-CD32/CD16 (FcγII/III receptor, 2.4G2, Pharmingen) for 5 min before the addition of primary antibodies. The following antibodies were used according to the manufacturer's protocol: allophycocyanin-conjugated RA3-6B2 (α-B220) and 53-2.1 (α-Thy-1); FITC-conjugated S7 (α-CD43), 11-26c.2a (α-IgD), and 53-6.7 (α-CD8); phycoerythrin-conjugated GK1.5 (α-CD4) and 1B4B1 (α-IgM). All antibodies were obtained from Pharmingen with the exception of 1B4B1 (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Stained cells in 1 μg/ml propidium iodide were analyzed by using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) by gating on live cells. At least 20,000 events were collected per sample.

ELISA and Thymidine Incorporation Assays. Serum Ig concentrations were measured with the ELISA Clontyping System (Southern Biotechnology Associates). The plates were analyzed on an ELISA reader at 450 nm and compared with standards of known concentration (Southern Biotechnology Associates). Experiments were performed in triplicate. Two-tailed P values were determined by using the Student t test.

For the thymidine incorporation assay, B220+ cells were enriched from splenocytes by using α-B220 magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). Cells (105/ml) were plated in RPMI medium 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated FCS in the presence of 10 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (Sigma), 10 μg/ml α-CD40 (Pharmingen), and 50 ng/ml IL-4 (R & D Systems), or 1 μg/ml α-IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and IL-4. Cell proliferation was scored after 36 h by pulsing for 12 h with [methyl-3H]thymidine. Cells were harvested by using a Cell Harvester (PHD, Cambridge, MA) to determine [3H]thymidine incorporation.

Analyses of κ Light Chain V Region Usage. Pre-B cells (B220+IgM–CD43–) were pooled from 4–5 repopulated mice and isolated by using a MoFlo high-speed cell sorter (Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO). PCR amplification of κ V regions was performed by using a universal Vκ primer (52), and either a Jκ2orJκ5 downstream primer (53). PCR products were cloned into pCRII-TOPO (Invitrogen) and sequenced. For each genotype, Vκ segments from 100 independent transformants were identified by using igblast [National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)] and assigned by using the system of Thiebe et al. (54). A Fisher's exact test was applied by using statistical analysis software (matlab).

Results

Oct-1-Deficient Abelson-Transformed Pre-B Cells Display Reduced Oct-1 Activity. Previously, a mouse model of Oct-1 deficiency was generated by homologous recombination, replacing the third exon of the Oct-1 genomic locus with a neomycin cassette (47). This work established that Oct-1-deficient embryos die during development, precluding an analysis of the immune system in adult mice.

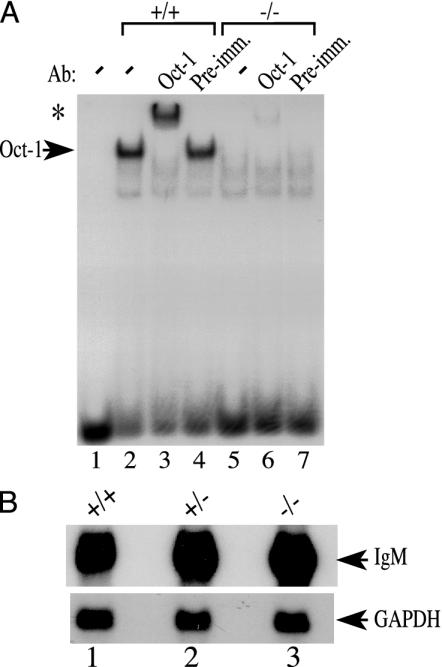

To circumvent this problem, adoptive transfer experiments were performed by using RAG-1-deficient mice as recipients. These animals lack the RAG-1 recombinase gene and cannot initiate VDJ rearrangement, making them devoid of B and T lymphocytes (55–57). Therefore, mature lymphocytes in these animals must be donor-derived. To determine whether the protein is reduced in Oct-1-deficient B cells, Abelson murine leukemia virus-transformed cell lines were generated from bone marrow pre-B cells derived from adoptively transferred mice. Oct-1 protein activity was assayed by using nuclear extracts derived from these immortalized pre-B cells and the electrophoretic mobility assay and nuclear extracts. Oct-1/DNA complex formation was undetectable in the Oct-1–/– nuclear extract preparation (Fig. 1, lane 5). No Oct-2 binding was obvious, presumably because Oct-2 levels are low in pre-B cells. The presence of Oct-1 in the observed protein–DNA complex was confirmed by supershift by using a monoclonal antibody recognizing a C-terminal epitope of the protein. Addition of the antibody resulted in the formation of a lower mobility protein–DNA complex (Fig. 1, lane 3). In contrast, no supershift was detected when preimmune serum was used (Fig. 1, lane 4). However, antibody supershift with Oct-1–/– nuclear extract revealed a slight amount of comigrating supershifted complex that was 35-fold lower in intensity compared with wild-type extract (Fig. 1, lane 6). The formation of both the Oct-1/DNA complex and the larger, supershifted complex depended critically on a canonical octamer element because a point mutation in the octamer element eliminated formation of the protein–DNA complex (data not shown). These data are in agreement with previous observations in primary murine embryonic fibroblasts in that there is an octamer-binding protein activity present in the wild-type nuclear extract that is specifically recognized by an α-Oct-1 antibody that is reduced at least 35-fold in Oct-1-deficient B cells (47).

Fig. 1.

(A) Electrophoretic mobility shift assay using Abelson murine leukemia virus-transfomed wild-type and Oct-1-deficient B cell extracts. Oct-1-DNA complexes formed with 5 μg of nuclear extract are shown by an arrow. Antibody-supershifted complexes are indicated by an asterisk. Preimmune serum (Pre-imm.) was used as a negative control. (B) Normal levels of Igμ transcripts in Oct-1 mutant cells. Northern blot is shown of RNA from splenic B cells stimulated with α-IgM and α-CD40. Ten micrograms of total RNA were loaded in each lane. GAPDH was used as a control.

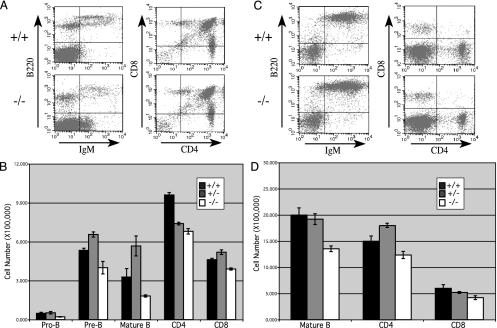

Oct-1 Is Dispensable for B Cell Development and Ig Expression. Fetal liver cells from wild-type and Oct-1-deficient embryos were injected into irradiated RAG-1 mice. The lymphoid compartments of the recipients were analyzed by flow cytometry 12–16 weeks postinjection. Bone marrow cells were stained with the pan-B cell marker B220 and a combination of stage-specific antibodies. Pro- and pre-B cells were identified by their lack of surface IgM and CD43+ and CD43– staining, respectively. Mature B cells coexpress surface IgM and IgD. The proportion of these cell types was not dramatically altered between wild-type and mutant mice (Fig. 2A). However, when quantified relative to total cell number, there was a reproducible reduction in B cell numbers for all stages of development (Fig. 2B). This reduction was specific for the B cell lineage because the T cell percentage and numbers remained the same. Splenic B cells were also analyzed by FACS. As with the bone marrow, the percentage of B cells remained similar (Fig. 2C), but a global decrease in the total number of cells was observed (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results suggest that Oct-1 is not required for B cell development and surface Ig expression but could be important for efficient B cell generation.

Fig. 2.

B cell development in Oct-1-deficient hematopoietic precursors. (A) Bone marrow cells from transferred recipients were stained with antibodies against B220, IgM, and CD43. T cells were stained with antibodies specific for Thy-1, CD4, and CD8. Shown are IgM vs. B220 stains for B cells and CD4 vs. CD8 stains of T cells. For upper right quadrants, percentages are as follows: IgM vs. B220, 8.1% for +/+ and 3.1% for –/–; CD4 vs. CD8, 85.5% for +/+ and 82.8% for –/–. (B) Quantification of B cell subsets: pro-B cells, B220+IgM–CD43+; pre-B cells, B220+IgM–CD43–; mature B cells, B220+IgM+IgD+. To obtain cell number for each group, the percentage of each subset was extrapolated from the FACS plot and multiplied by the total number of cells in each preparation. For each value, data were collected from at least three repopulated mice. SDs are indicated by error bars. (C) Spleen cells were stained for B220, IgM, and IgD or for Thy-1, CD4, and CD8. B220 and CD4 vs. CD8 are shown. For upper right quadrants, percentages were 61.8% for +/+ and 62.4% for –/–. (D) Total numbers of mature B cells in the spleen, determined as in B. Mature B cells, B220+IgM+IgD+.

For B cells in both bone marrow and spleen, the levels of Ig expression seemed to be the same in the presence and absence of Oct-1, and the mean and maximal surface staining was the same in each case (Figs. 2 A and C). To verify that the levels of messenger RNA were also the same, Northern blot analysis was performed by using RNA purified from splenic B cells that were stimulated with anti-IgM and anti-CD40 antibodies and a probe corresponding to the μ heavy chain constant region. When normalized to the GAPDH control, the degree of μ mRNA expression was the same in each case (Fig. 1B).

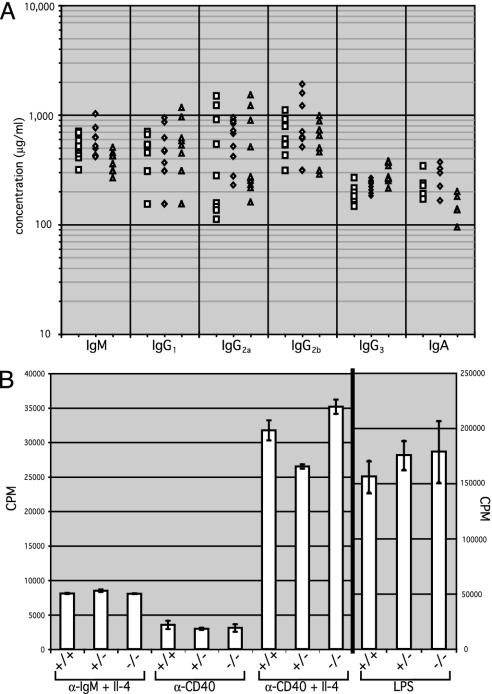

The concentration of serum Ig isotypes was measured in recipient mice by using ELISA (Fig. 3A). IgM and IgA showed a moderate but selective decrease of ≈2-fold relative to wild type and heterozygotes (P = 0.0034 for IgM) whereas the IgG isotypes showed no change (P = 0.4824 for IgG1). This finding is consistent with the slight decrease in total numbers of surface Ig-expressing mature B cells, rather than a selective defect in class switching.

Fig. 3.

(A) Serum concentrations of Ig isotypes in nonimmunized adoptive transfer recipients were measured by ELISA with isotype-specific antibodies. Each symbol represents one mouse. Squares, wild-type; diamonds, Oct-1 heterozygotes; triangles, Oct-1 homozygous mutant animals. (B) Activation and proliferation of Oct-1-deficient B cells as measured by thymidine incorporation assay. Data represent an average of five experiments. Error bars denote SDs. Conditions are described in Materials and Methods.

Normal Proliferation in Vitro of Oct-1-Deficient B Cells. To test whether Oct-1-deficient B cells can proliferate in response to antigenic stimuli, B220+ splenic B cells were purified and stimulated with either T cell-dependent or T cell-independent antigens. Although Oct-2-deficient B cells fail to respond to the T cell-independent polyclonal stimulator lipopolysaccharide, Oct-1-deficient B cells proliferated comparably to wild-type B cells under all conditions tested (Fig. 3B). Therefore, in contrast to Oct-2–/– B cells, Oct-1-deficient B cells demonstrate normal proliferative capacity in vitro when stimulated with either T cell-dependent or T cell-independent antigens.

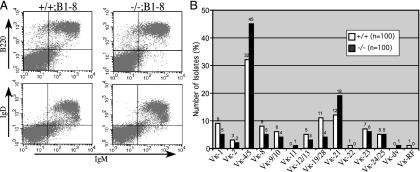

Oct-1-Deficient B Cells Develop Normally in Mice That Express a Single Heavy Chain Specificity. Oct-1–/+ mice were crossed to the B1-8 strain, which harbors a rearranged VDJ transgene targeted into the heavy chain locus and generates a single heavy chain specificity due to allelic exclusion (49). The B1-8 (also known as 186.2) promoter belongs to the J558 class and contains consensus octamer and heptamer elements. Oct-1–/+;B1-8 mice were intercrossed to generate Oct-1–/–;B1-8 embryos. Analysis of the splenic B cell profile of the adoptive transfer recipients did not reveal any significant difference between wild-type and Oct-1-deficient mice except for a slight decrease in B cell number (Fig. 4A). The mean and maximum levels of surface Ig expression between the two populations remained the same, suggesting that there is no difference in transcription efficiency. In addition, no differences were observed in the profiles of bone marrow or peripheral blood (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

(A) Surface phenotype of Oct-1–/–;B1-8 B cells. Splenocytes from recipient mice were stained for B220, IgM, and IgD. For upper right quadrants, percentages are as follows: IgM vs. B220, 29.2% for +/+ and 31.6% for –/–; IgM vs. IgD, 27.2% for +/+ and 30.5% for –/–. (B) Vκ family usage of B cells purified from the bone marrow of RAG-1 mice adoptively transferred with Oct-1+/+ or Oct-1–/– mutant fetal liver cells. Total number of isolates is shown at the top each column.

Normal Light Chain Variable Segment Utilization in Oct-1 Mutant Mice. If, in the absence of Oct-1 most V region promoters are impaired but some retain activity and allow normal B cell development and Ig expression, then there would be significant changes in the utilization of V region gene segments. To test the usage of the κ light chain variable region segments, Vκ family utilization was examined in pre-B cells (B220+IgM–CD43–) from the bone marrow of RAG-1-recipient mice repopulated with either wild-type or Oct-1 mutant fetal liver cells. These cells were chosen because presumably they have not undergone selection by peripheral antigens. Rearranged VκJκ segments were amplified by using a universal Vκ PCR primer (52) and a primer downstream of either Jκ2orJκ5, generating an equivalent banding pattern for all genotypes (data not shown). Amplified gene segments were identified by comparison with the germ-line V region database by using igblast (NCBI) and were assigned into one of the Vκ families by using the system of Thiebe et al. (54).

Assignment of 100 independent clones from wild-type and Oct-1 mutant B cells resulted in a spectrum of Vκ gene usage consistent with published accounts, with Vκ4/5 as the dominant family (Fig. 4B). Application of the Fisher exact test resulted in a statistically nonsignificant P value of 0.3, indicating that the differences in Vκ gene segment utilization between wild-type and Oct-1 mutant B cells, if any, are few and minor.

Discussion

A mouse model of Oct-1 deficiency was generated by using a targeting strategy in which exon 3 of Oct-1 was replaced with a neomycin resistance cassette in the antisense transcriptional orientation (47). Although skipping of this exon leads to a frameshift mutation and truncation of the Oct-1 polypeptide before the DNA binding domain, some residual Oct-1 DNA-binding activity (2–3%) was observed in murine embryonic fibroblasts and B cells derived from these mice, and therefore the Oct-1 mutation should be considered a severely hypomorphic allele. Oct-1 homozygous mutant mice die before birth, possibly from erythropoietic defects (47). We present here an analysis of Oct-1 function during lymphoid development by using adoptive transfer to RAG-1 recipients. We find that Oct-1 is not required for B cell development and Ig gene transcription in vivo. B cell numbers in the bone marrow and spleen, as well as serum IgM and IgA, were slightly lower than wild-type controls, and cultured B cells were fully capable of responding to both T cell-dependent and -independent antigens. Overall, the results suggest that Oct-1 has no independent role in B cell development and Ig transcription.

In both the Ig heavy and light chain loci, the V region gene segments and their promoters are present in tandem arrays on the chromosome. RAG-mediated recombination selects one of these promoters for rearrangement to a Jκ segment in the case of the light chain, or a DH and JH segment in the case of the heavy chain. Because of these features, it was possible that the loss of Oct-1 impacted most of the variable gene segments, but that one or more segments remained sufficiently active to retain their recombination potency and produce full levels of Ig. One way to test this possibility is to reduce the genomic complexity of the multiple VH promoters to a single specificity. The B1-8 mouse model (48, 49) harbors a pre-recombined VDJ heavy chain knocked into the IgH locus and produces heavy chain polypeptides of a single specificity driven by a promoter that contains consensus octamer and heptamer motifs. By using this model, no significant differences in either the proportion of B cells produced or the level of Ig expression were observed. To further determine whether a subgroup of V gene segments were being selectively expressed in the Oct-1-deficient cells, the diversity of the light chain usage was also analyzed. All major classes of V segment gene families were used at approximately the same levels. These results contrast with recent studies of the B cell-specific coactivator OCA-B in which significant differences in the Vκ repertoire were observed (58).

Although Oct-1 deficiency does not result in any B cell-specific defects, previous work established an important role for Oct-2 during the terminal antigen-dependent phase of B cell maturation, particularly in antigen-dependent proliferation (35, 36). Genetic ablation of OCA-B also results in late-stage B cell developmental defects (44, 45). Therefore, Oct-2 and OCA-B seem to play a role in B cell maturation. By contrast, Oct-1 either plays no role in these processes or is redundant with Oct-2 and OCA-B.

These findings are somewhat inconsistent with previous biochemical and transient transfection experiments, which had suggested an important function for Oct-1 in the regulation of Ig expression. Previous work had indicated that Oct-1 and Oct-2 activate transcription equally in vitro (32). Other studies using cell lines and transfections indicated that Oct-2 operates through the Ig enhancer regions, implicating another factor such as Oct-1 at the VH and Vκ octamer elements (38, 39). The strong conservation in the octamer elements in this promoter points toward three possible scenarios. (i) The octamer sequence is conserved because of its interactions with Oct-2, which is primarily responsible for transcriptional activation from the octamer element in both the promoters and enhancers. In the absence of Oct-2, Oct-1 can partially substitute, providing enough activity for B cell development and initial Ig expression but not for later stage B cell activation. In this case, Oct-1 and Oct-2 would operate redundantly at the VH promoters in B cells. (ii) Neither Oct-2 nor Oct-1 is required for V region promoter activity in B cells. VH and Vκ promoter activity would not be compromised in the absence of these factors, possibly because of other promoter elements such as E boxes, pyrimidine-rich, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein, and Ets transcription factor-binding sites, and newly defined downstream promoter elements (59–63). In this case, Oct-2 would have a major role in late-stage B cell biology through its interactions with Ig enhancer elements. (iii) Neither Oct-2 nor Oct-1 is required for Ig activity, and the requirement for Oct-2 in late-stage B cell activation is mediated through sites other than those in the Ig loci. As a means of distinguishing among these scenarios, in the latter two, an Oct-1–/–; Oct-2–/– double mutant phenotype would be no more severe with regard to Ig expression and B cell development than the Oct-2–/– single mutant.

Generation of compound mutants of Oct-1 with Oct-2, OCA-B, and other factors thought to be important in the control Ig expression may provide additional insight into the role of these proteins in B cell development. We have previously reported that Oct-1 and Oct-2 exhibit a dosage-dependent effect in mediating embryonic survival (47). However, preliminary studies have also shown that although Oct-1+/–;Oct-2+/– transheterozygotes display reduced survival, they do not exhibit any detectable difference in B cell profile and function compared with wild-type littermates. Oct-1–/–;Oct-2+/– and Oct-1+/–;Oct-––/– fetal livers also show no marked B cell abnormalities in adoptive transfer experiments whereas double mutant embryos do not survive to embryonic day 11.5 (unpublished results). To determine the role of Oct-1 and Oct-2 together in B cell development, the activity of both proteins must be ablated in the immune system by using RNA interference or other means.

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Novobrantseva and Q. Ge for helpful discussion and technical advice; W. Leonard and members of the Sharp laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript; G. Paradis, M. Doire, and M. Jennings for assistance with FACS; D. Cook for DNA sequencing; P. Matthias for advice and reagents; and M. Siafaca for assistance. The Abelson virus was a gift from N. Rosenberg. The B1-8 transgenics were obtained from K. Rajewsky. V.E.H.W. was supported by a Howard Hughes Predoctoral Fellowship and the David Koch Graduate Fellowship. D.T. was supported by fellowships from the Irvington Institute for Immunological Research and The Medical Foundation, Charles A. King Trust. This work was funded by U.S. Public Health Service Grants PO1-CA42063 (to P.A.S.) and A140416 (to J.C.) and partially by Cancer Center (Core) Support Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviation: FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorter.

References

- 1.Henderson, A. & Calame, K. (1998) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 16, 163–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballard, D. W. & Bothwell, A. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 9626–9630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falkner, F. G. & Zachau, H. G. (1984) Nature 310, 71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mason, J. O., Williams, G. T. & Neuberger, M. S. (1985) Cell 41, 479–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parslow, T. G., Blair, D. L., Murphy, W. J. & Granner, D. K. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81, 2650–2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wirth, T., Staudt, L. & Baltimore, D. (1987) Nature 329, 174–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda, F., Ishii, K., Bourvagnet, P., Kuma, K., Hayashida, H., Miyata, T. & Honjo, T. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 188, 2151–2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenuwein, T. & Grosschedl, R. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 932–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreyfus, M., Doyen, N. & Rougeon, F. (1987) EMBO J. 6, 1685–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen, S. M., Martin, B. K., Tan, S. S. & Weis, J. H. (1992) J. Immunol. 148, 3610–3617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamps, M. P., Corcoran, L., LeBowitz, J. H. & Baltimore, D. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 5464–5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konig, H., Pfisterer, P., Corcoran, L. M. & Wirth, T. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1598–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmoud, M. S. & Kawano, M. M. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 228, 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeuffer, I., Klein-Hessling, S., Heinfling, A., Chuvpilo, S., Escher, C., Brabletz, T., Hentsch, B., Schwarzenbach, H., Matthias, P. & Serfling, E. (1994) J. Immunol. 153, 5572–5585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shore, P., Dietrich, W. & Corcoran, L. M. (2002) Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 1767–1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thevenin, C., Lucas, B. P., Kozlow, E. J. & Kehrl, J. H. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 5949–5956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, L. & Nabel, G. J. (1994) Cytokine 6, 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfisterer, P., Hess, J. & Wirth, T. (1997) Immunobiology 198, 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunderson, S. I., Murphy, J. T., Knuth, M. W., Steinberg, T. H., Dahlberg, J. H. & Burgess, R. R. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 17603–17610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy, J. T., Burgess, R. R., Dahlberg, J. E. & Lund, E. (1982) Cell 29, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sive, H. L., Heintz, N. & Roeder, R. G. (1986) Mol. Cell. Biol. 6, 3329–3340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sive, H. L. & Roeder, R. G. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 83, 6382–6386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staudt, L. M., Clerc, R. G., Singh, H., LeBowitz, J. H., Sharp, P. A. & Baltimore, D. (1988) Science 241, 577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staudt, L. M., Singh, H., Sen, R., Wirth, T., Sharp, P. A. & Baltimore, D. (1986) Nature 323, 640–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh, H., Sen, R., Baltimore, D. & Sharp, P. A. (1986) Nature 319, 154–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheidereit, C., Cromlish, J. A., Gerster, T., Kawakami, K., Balmaceda, C. G., Currie, R. A. & Roeder, R. G. (1988) Nature 336, 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clerc, R. G., Corcoran, L. M., LeBowitz, J. H., Baltimore, D. & Sharp, P. A. (1988) Genes Dev. 2, 1570–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pruijn, G. J., van Driel, W. & van der Vliet, P. C. (1986) Nature 322, 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturm, R. A. & Herr, W. (1988) Nature 336, 601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verrijzer, C. P., Alkema, M. J., van Weperen, W. W., Van Leeuwen, H. C., Strating, M. J. & van der Vliet, P. C. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 4993–5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ingraham, H. A., Albert, V. R., Chen, R. P., Crenshaw, E. B., 3rd, Elsholtz, H. P., He, X., Kapiloff, M. S., Mangalam, H. J., Swanson, L. W., Treacy, M. N., et al. (1990) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 52, 773–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeBowitz, J. H., Kobayashi, T., Staudt, L., Baltimore, D. & Sharp, P. A. (1988) Genes Dev. 2, 1227–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoykova, A. S., Sterrer, S., Erselius, J. R., Hatzopoulos, A. K. & Gruss, P. (1992) Neuron 8, 541–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muller, M. M., Ruppert, S., Schaffner, W. & Matthias, P. (1988) Nature 336, 544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corcoran, L. M., Karvelas, M., Nossal, G. J., Ye, Z. S., Jacks, T. & Baltimore, D. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 570–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corcoran, L. M. & Karvelas, M. (1994) Immunity 1, 635–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humbert, P. O. & Corcoran, L. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 159, 5273–5284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feldhaus, A. L., Klug, C. A., Arvin, K. L. & Singh, H. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 2763–2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang, H. & Sharp, P. A. (1999) Immunity 11, 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gstaiger, M., Knoepfel, L., Georgiev, O., Schaffner, W. & Hovens, C. M. (1995) Nature 373, 360–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo, Y. & Roeder, R. G. (1995) Mol. Cell. Biol. 15, 4115–4124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strubin, M., Newell, J. W. & Matthias, P. (1995) Cell 80, 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zwilling, S., Dieckmann, A., Pfisterer, P., Angel, P. & Wirth, T. (1997) Science 277, 221–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim, U., Qin, X. F., Gong, S., Stevens, S., Luo, Y., Nussenzweig, M. & Roeder, R. G. (1996) Nature 383, 542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nielsen, P. J., Georgiev, O., Lorenz, B. & Schaffner, W. (1996) Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 3214–3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schubart, K., Massa, S., Schubart, D., Corcoran, L. M., Rolink, A. G. & Matthias, P. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, V. E. H., Schmidt, T., Chen, J., Sharp, P. A. & Tantin, D. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 1022–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taki, S., Meiering, M. & Rajewsky, K. (1993) Science 262, 1268–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sonoda, E., Pewzner-Jung, Y., Schwers, S., Taki, S., Jung, S., Eilat, D. & Rajewsky, K. (1997) Immunity 6, 225–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unnikrishnan, I., Radfar, A., Jenab-Wolcott, J. & Rosenberg, N. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4825–4831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dignam, J. D., Lebovitz, R. M. & Roeder, R. G. (1983) Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlissel, M. S. & Baltimore, D. (1989) Cell 58, 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen, J., Young, F., Bottaro, A., Stewart, V., Smith, R. K. & Alt, F. W. (1993) EMBO J. 12, 4635–4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thiebe, R., Schable, K. F., Bensch, A., Brensing-Kuppers, J., Heim, V., Kirschbaum, T., Mitlohner, H., Ohnrich, M., Pourrajabi, S., Roschenthaler, F., et al. (1999) Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 2072–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shinkai, Y., Koyasu, S., Nakayama, K., Murphy, K. M., Loh, D. Y., Reinherz, E. L. & Alt, F. W. (1993) Science 259, 822–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen, J., Lansford, R., Stewart, V., Young, F. & Alt, F. W. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 4528–4532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mombaerts, P., Iacomini, J., Johnson, R. S., Herrup, K., Tonegawa, S. & Papaioannou, V. E. (1992) Cell 68, 869–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Casellas, R., Jankovic, M., Meyer, G., Gazumyan, A., Luo, Y., Roeder, R. & Nussenzweig, M. (2002) Cell 110, 575–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooper, C., Johnson, D., Roman, C., Avitahl, N., Tucker, P. & Calame, K. (1992) J. Immunol. 149, 3225–3231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eaton, S. & Calame, K. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 7634–7638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hatada, E. N., Chen-Kiang, S. & Scheidereit, C. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 174–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwarzenbach, H., Newell, J. W. & Matthias, P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 898–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tantin, D., Tussie-Luna, M.-I., Roy, A. L. & Sharp, P. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]