Abstract

Background

Mountain ecosystems all over the world support a high biological diversity and provide home and services to some 12% of the global human population, who use their traditional ecological knowledge to utilise local natural resources. The Himalayas are the world's youngest, highest and largest mountain range and support a high plant biodiversity. In this remote mountainous region of the Himalaya, people depend upon local plant resources to supply a range of goods and services, including grazing for livestock and medicinal supplies for themselves. Due to their remote location, harsh climate, rough terrain and topography, many areas within this region still remain poorly known for its floristic diversity, plant species distribution and vegetation ecosystem service.

Methods

The Naran valley in the north-western Pakistan is among such valleys and occupies a distinctive geographical location on the edge of the Western Himalaya range, close to the Hindu Kush range to the west and the Karakorum Mountains to the north. It is also located on climatic and geological divides, which further add to its botanical interest. In the present project 120 informants were interviewed at 12 main localities along the 60 km long valley. This paper focuses on assessment of medicinal plant species valued by local communities using their traditional knowledge.

Results

Results revealed that 101 species belonging to 52 families (51.5% of the total plants) were used for 97 prominent therapeutic purposes. The largest number of ailments cured with medicinal plants were associated with the digestive system (32.76% responses) followed by those associated with the respiratory and urinary systems (13.72% and 9.13% respectively). The ailments associated with the blood circulatory and reproductive systems and the skin were 7.37%, 7.04% and 7.03%, respectively. The results also indicate that whole plants were used in 54% of recipes followed by rhizomes (21%), fruits (9.5%) and roots (5.5%).

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate the range of ecosystem services that are provided by the vegetation and assess how utilisation of plants will impact on future resource sustainability. The study not only contributes to an improved understanding of traditional ethno-ecological knowledge amongst the peoples of the Western Himalaya but also identifies priorities at species and habitat level for local and regional plant conservation strategies.

Keywords: Biodiversity conservation, Ecosystem services, Medicinal plants, Vegetation

Introduction

The benefits obtained by humans from nature are termed as Ecosystem Services [1,2]. Natural ecosystems provide human societies with vital supporting services, such as air and water purification, climate regulation, waste decomposition, soil fertility & regeneration and continuation of biodiversity. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2003) and few other studies of ecosystem services have classified these services into four broad categories – provisioning, regulating, supporting and cultural [3-8]. These services are produced by complex interactions between the biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems. All kinds of ecosystem services, whether provisioning, regulating, supporting or cultural, are closely allied to plant biodiversity [9,10]. All sort of these services ultimately contribute to agricultural, socio economic and industrial activities [11-13]. Plant biodiversity on slope surfaces of the mountains regulates supply of good quality water and prevents soil erosion and floods. It also enhances soil formation, fertility, nutrient and other biogeochemical cycling. Provisioning services provided by plant biodiversity are in the form of food, grazing land and fodder for their livestock, fuel wood, timber wood, and medicinal products. Culturally, people utilize plants in number of ways like aesthetics, religion, education, naming etc.

People extensively utilize the predominant herbaceous flora of mountainous ecosystems by keeping cattle and multipurpose collection, both of which cause over-exploitation of the vegetation and risks to the continuation of plant biodiversity. In order to develop appropriate systems for the sustainable use of plant resources, it is crucial to understand how traditional uses of plants influence biodiversity in these ecosystems. A plant that possesses therapeutic properties or exerts beneficial pharmacological effects on the human or animal body is generally designated as “medicinal plant”. It has also been recognized that these plants naturally synthesize and accumulate some secondary metabolites, like alkaloids, glycosides, tannins, volatile oils, minerals and vitamins, possess medicinal properties [14,15]. A number of medicinal plants possess some special characteristics that make them special in those mountainous regions of the Himalayas and adjacent ranges [16,17]. Medicinal plants constitute an important natural wealth of that region and ultimately at national level. They play a significant role in providing primary health care services to rural people [18]. They serve as healing agents as well as important raw materials for the manufacturing of traditional and modern medicine [19]. Similarly a substantial amount of foreign exchange can be earned through exporting medicinal plants to other countries. In this way indigenous medicinal plants play significant role of an economy of a country. This paper therefore, sought to, not only studies the natural vegetation of the Naran Valley, but also to the indigenous people of the valley in an assessment and identification of the plant species of therapeutic uses.

Study area

The Naran Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistanis is about 60 km long valley and can be located at 34° 54.26’N to 35° 08.76’ N latitude and 73° 38.90’ E to 74° 01.30’ E longitude; elevation between 2450 to 4100 m above mean sea level. The entire area is formed by high spurs of mountains on either side of the River Kunhar which flows in a northeast to southwest direction down the valley to the town of Naran. Geographically, the valley is located on the extreme western boundary of the Himalayan range, after which the Hindu Kush range of mountains starts to the west of the River Indus. Geologically, the valley is situated on the margin of the Indian Plate where it is still colliding against the Eurasian plate (Figure 1). Floristically, the valley has been recognised as an important part of the Western Himalayan province [20], while climatically, it has a dry temperate climate with distinct seasonal variations.

Figure 1.

Physiographic map (produced through Arch GIS) of the Naran Valley; elevation zones, location of its main settlements (A-L), the River Kunhar, originating lake (the Lake Lulusar) and the tributary streams. (Elevation data obtained from the ASTER GDEM, a product of METI and NASA).

Methodology for ethnobotanical data collection and analyses

An ethno-ecological study was carried out to explore how the local people interact with natural plant biodiversity. Interviews using questionnaires were organized during summer (May-September) 2010. Data was collected in two phases i.e., field survey and questionnaire survey.

a) Observations of local people during first fieldwork (summer, 2009) about the utilization of plant biodiversity for various purposes were used for the questionnaire preparation. A mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection was adopted in preparing a questionnaire for collecting indigenous knowledge about plant species. Local names of plants were listed along with the botanical names of the recorded 198 plant species [21,22]. Plant species photographed during the first field campaign were shown to the interviewees where and when it was felt necessary.

b) Each of the main 12 localities (A-L) in the project area (at an interval of about 5 km each), where vegetation transects had been taken, were revisited (Figure 1). Meetings were arranged with village heads or councillors and permission as well as guidance was obtained. Ethnic groups including the Gujars, Syeds, Swati and Kashmiri inhabit the valley. The most important among these are the Gujars (descendents of the Indian Arians) who are famous for their unique culture, way of life, rituals and bravery. The Gujars are concentrated in the upper parts of most valleys in Pakistan where they cultivate rain-fed slopes, and are generally more aware of traditional knowledge, of plant use and local ecology. A local community member of these tribes was taken as a guide who knew the norms and traditions of that indigenous society [23,24]. Ten houses at each of the 12 main localities of the Valley (a total of 120) were selected randomly for the interviews, using a random number table. Each village was visited from one side; a coin was tossed in front of each 5th house and if it fall head side up, then an interview was requested from that family [24,25]. If willing, one member in the household was interviewed about their uses of plants, preferences, therapeutic application and plant part that were used. Informants were asked about their general uses of plant species, e.g. as food, fodder, grazing, timber, fuel, aesthetic, medicinal and others. Respondent were then asked about their species preference if they utilised a species for several purposes – food, fodder, grazing, fuel, timber or medicinal purposes. As there was much preference for medicinal uses of plants and hence informants were further asked for details about the plant part(s) that were used, the diseases it cured and the recipe of use.

Questionnaire data was initially analyzed for basic categorization of the respondents’ gender, age groups and literacy ratio etc. This data was additionally analyzed for use preferences, plants parts used, recipes and treatment categorization with slight changes to the methodology adopted by [26-28].

Results

Preliminary information about the respondents

The questionnaire respondents represented a diverse array of people including farmers, women, literate, illiterate, young and elders. Among the 120 informants, 87 were male and 33 were female. The largest proportion of the respondents was of elderly, above 40 years old (81.6%) (Table 1). More than half of the respondents were illiterate (51.7%), whilst, most of those with an education had merely primary which reflect the unavailability of educational institution in the area (30%) (Table 1). These very basic results also reflect the reality that indigenous knowledge is well established but seems to be decreasing in the younger generation.

Table 1.

Age group and literacy level frequencies of the interviewed people in the region

| Age group | No. of Individuals | Percentage | Literacy Level | No. of Individuals | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14-30 |

6 |

5.0 |

Illiterate |

62 |

51.7 |

| 31-40 |

16 |

13.3 |

Primary |

36 |

30.0 |

| 41-50 |

41 |

34.2 |

Middle |

11 |

9.2 |

| 51-60 |

43 |

35.8 |

Secondary |

10 |

8.3 |

| 61-70 + | 14 | 11.7 | University | 1 | 0.8 |

Preference analysis

Many of the recorded species (83%) provide a number of provisioning services and hence the respondents were asked what preference they gave for a specific service category. The results of preference analysis showed the highest priority of local people for medicinal use of plant species (56.9% responses) followed by grazing and food (13.1% and 10.8% respectively) (Figure 2). The high priority given to medicinal use illustrates the high level of traditional knowledge about plants in the community and the lack of basic health facilities. It can also be attributed to the high market value of medicinal species.

Figure 2.

Preferences mentioned by the informants for the species having more than one local use.

As people of the region preferred the plants for therapeutic purposes and hence detailed analyses were carried out on medicinal services.

Ethnomedicinal plant resources

People in the valley use 101 species belonging to 51 families (51% of the total plants) for medicinal purposes (55.4% of the used species). Lamiaceae, with 9 species, was the most represented medicinal family followed by Polygonaceae and Rosaceae with 8 species each.

Important medicinal plant species

Each medicinal species found in the region is noteworthy but a few of them got much importance in the local health care system e.g., Dioscorea deltoidea is locally used in urinary tract problems, as tonic and anthelmintic. Local hakeems (experts in traditional medicine) use Podophyllum hexandrum) in digestive troubles and treating cancer. Powdered bark of Berberis pseudoumbellata is locally utilized for the treatment of fever, backache, jaundice and urinary tract infection whilst its fruit is valued as a tonic. Orchid species i.e., Cypripedium cordigerum and Dactylorhiza hatagirea are considered as aphrodisiacs and as nerve tonics. Other noteworthy medicinal species are Cedrus deodara and Aesculus indica. Oils extracted from Cedrus deodara are used in skin diseases while powder of the dried fruit nuts of Aesculus indica are used in colic and also as worm expeller. Among other species, Aconitum heterophyllum, Aconitum violaceum, Ephedra gerardiana, Eremurus himalaicus, Hypericum perforatum, Indigofera heterantha, Geranium wallichianum, Iris hookeriana, Nepeta laevigata, Origanum vulgare, Paeonia emodi, Rheum austral, Thymus linearis and Ulmus wallichiana are also of great importance in the traditional health care. For detailed use of each species see Table 2.

Table 2.

Plant species with their local names, part used and traditional medicinal uses

| S. N | Botanical Name | Family Name | Altitude (m) | Locality | Local Name | Part used | Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Achillea millefolium L. |

Asteraceae |

2840 |

Bans |

Birangesif/Jarri |

Whole plant |

Less concentrated decoction mixed with milk is taken in stomach disorders and diarrhoea. |

| 2 |

Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. |

Ranunculaceae |

3250 |

Besal |

Patris/Sarba vala |

Rhizome |

Pills of rhizome powder coated in local butter are used as aphrodisiac and general body tonic. |

| 3 |

Aconitum violaceum Jacq. ex Stapf |

Ranunculaceae |

3310 |

Serrian |

Atees/Zahar |

Paired roots |

Powders are used in sciatica and as pain killer. |

| 4 |

Actaea spicata L. |

Rosaceae |

3130 |

Lalazar |

Beenakae |

Root, berries |

Berries are used as sedative; Extract is applied externally for the treatment of joint pains. |

| 5 |

Adiantum venustum D. Don |

Adiantaceae |

3020 |

Upper Batakundi |

Sumbal |

Whole plant |

Infusion is taken orally for lungs disorders. |

| 6 |

Aesculus indica (Wall. ex Camb) Hook. |

Hippocastanceae |

2460 |

Damdama |

Bankhore/Javaz |

Fruit |

Powder of the dried fruit is used in indigestion. |

| 7 |

Allium humile Kunth. |

Alliaceae |

3570 |

Lalazar Peak |

Jangali piaz |

Whole plant |

Fresh plant is taken as salad for gastrointestinal disorders and UTI. |

| 8 |

Angelica glauca Edgew. |

Apiaceae |

3410 |

Lalazar |

Chora chora |

Dried roots |

Powdered roots are taken with milk for gastrointestinal disorders. |

| 9 |

Artemisia absinthium L |

Asteraceae |

2800 |

Lalazar |

Chahu/Tarkha |

Flowering tops |

Crushed powders are used to enhance digestion as well as worm problems. |

| 10 |

Artemisia vulgaris L. |

Asteraceae |

2630 |

Batakundi R. Station |

Chahu/Javkey |

young shoots |

Extract of its young shoots is used to regulate monthly cycle. |

| 11 |

Asparagus racemosus Willd. |

Asparagaceae |

2770 |

Barrawae |

Nanoor/Shalgvatey |

Root & stem |

Paste of powder is applied for wounds healing (Antiseptic); powders are taken orally to stimulates sexual desire and treat dysentery. |

| 12 |

Berberis pseudoumbellata Parker |

Berberidaceae |

2900 |

Batakundi |

Sumbal/Kvarey |

Root, bark & fruit |

Powder of roots bark is used in fever, backache, jaundice, and UTI. Fruit is considered as tonic. |

| 13 |

Bergenia ciliata (Haw.) Sternb. |

Saxifragaceae |

2940 |

Upper Batakundi |

But pewa/Zakhme hayat |

Latex & Rhizome |

Latex is applied externally for gum diseases and decoction of rhizome is used in kidney stones. |

| 14 |

Bergenia strachyei (Hook. f. & Thoms) Engl |

Saxifragaceae |

3190 |

Such Peak |

But pewa/Zakhme hayat |

Rhizome, Latex |

Latex is applied externally for gum diseases; Decoction of rhizome is used in kidney stones and for contraction of tissues. |

| 15 |

Betula utilis D. Don |

Betulaceae |

3250 |

Such |

Braj |

Leaves, bark |

Tea made up of young leaves is used as diuretic and joints pain; rarely used for gall bladder stone. |

| 16 |

Bistorta affinis (D. Don) Green |

Polygonaceae |

3350 |

Lower Batakundi |

Anjabar |

Rhizome |

Powders prepared from rhizome taken with milk in fever, body pains & muscles contraction. |

| 17 |

Bistorta amplexicaulis (D. Don) |

Polygonaceae |

2680 |

Batakundi R. Station |

Masloon |

Rhizome |

Powder mixed with little salt is used for sore throat, swelling of mouth and tongue. |

| 18 |

Caltha alba Jack. ex Comb |

Ranunculaceae |

2960 |

Khora |

Baringu |

Roots & airial parts |

Roots infusion is used as mouth wash; young shoots and leaves are cooked as vegetable for and considered as digestive. |

| 19 |

Capsella bursa-pastoris (L.) Medic. |

Brassicaceae |

2540 |

Lower Batakundi |

Chambraka |

Aerial parts, seeds |

Aerial parts are cooked and used in diarrhoea; Seeds powder is taken with water to cure high blood pressure. |

| 20 |

Cedrus deodara (Roxb. ex Lamb.) G. Don |

Pinaceae |

2700 |

Naran |

Diar/Ranzrra |

oil |

Oil are extracted from wood through burning and used to cure skin disorders. |

| 21 |

Chenopodium album L. |

Chenopodiaceae |

2460 |

Naran |

Sarmay |

Leaves & shoots |

Leaves and shoots are cooked and taken to expel worms also to promote evacuation of bowels and urine. |

| 22 |

Clematis montana Buch.-Ham. ex DC |

Ranunculaceae |

2820 |

Lalazar |

Zelae |

Flowers & Fruits |

Flowers and fruits powder is taken for treating the diarrhoea & dysentery. |

| 23 |

Colchicum luteum Baker |

Colchicaceae |

3230 |

Bans |

Qaimat-guley/Suranjane talkh |

Dried corms |

Very small amount of powder is given by Hakims (specialist people) in local oils as aphrodisiac and in joint pains, spleen & liver diseases. |

| 24 |

Convolulus arvensis L. |

Convolulaceae |

2940 |

Upper Batakundi |

Sahar gulay |

Roots |

Powder is considered as purgative & used in evacuation of bowels. |

| 25 |

Corydalis govaniana Wall. |

Fumariaceae |

3310 |

Damdama |

Desi mamera |

Whole plant |

Juice o the plant is used as diuretic powders of flowers are used in treating eye diseases. |

| 26 |

Cotoneaster microphyllus Wall. ex Lindl |

Rosaceae |

2720 |

Dadar Nalah |

Mamanna/Kharava |

Leaves and shoots |

Tea prepared from leaves is used to stop bleeding and peep. |

| 27 |

Crataegus oxycantha L. |

Rosaceae |

2410 |

Naran |

Tampasa |

Fruits and flowers |

Fruit and flowers are considered as heart tonic. |

| 28 |

Cypripedium cordigerum D. Don |

Orchidaceae |

3050 |

Batakundi |

Shakalkal |

Rhizome |

Powders are used by experts relieve spasm and as nerve stimulant |

| 29 |

Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D. Don) Soo |

Orchidaceae |

2760 |

Saifalmaluk Nalah |

Salap |

Tubers |

Tubers powders are used by hakims as sex stimulant & nerve tonic. |

| 30 |

Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. |

Dioscoreaceae |

2820 |

Damdama |

Kirtha |

Tubers |

Tubers are crushed to powder form and uses as enhancer of excretion and worm expulsion; Also used in butter as tonic. |

| 31 |

Dryopteris juxtapostia Christ |

Pteridaceae |

2910 |

Upper Batakundi |

Kwanjay |

Young shoots |

Young shoots are cooked as pot herb and considered as digestive that help in evacuation of bowel more drastically. |

| 32 |

Ephedra gerardiana Wall. ex Stapf |

Ephedraceae |

2570 |

Batakundi R. Station |

Ephedra |

Whole plant |

Powder of the crushed plant and some time its tea is used for TB, asthma, astringent, relaxation of bronchial muscles. |

| 33 |

Equisetum arvense L. |

Equisetaceae |

2600 |

Batakundi R. Station |

Nari/Bandakey |

Aerial parts |

Powder prepare from aerial parts are used for bone strengthening, hairs and nail development and weakness caused by TB. |

| 34 |

Eremurus himalaicus Baker |

Asphodelaceae |

2700 |

Barrawae |

Sheela |

Young shoots |

Young shoots are cooked and used as digestive. |

| 35 |

Euphorbia wallichii Hook. f. |

Euphorbiaceae |

3250 |

Such |

Arghamala/Shangla |

Latex |

Latex is extracted and mixed with milk in small amount and used against worms, to accelerate defecation, promotes circulation and bowel evacuation. |

| 36 |

Euphrasia himalayica Wetts. |

Lamiaceae |

3170 |

Lalazar |

|

Whole Plant |

Local people cook and use it against cold, cough, sore throat |

| 37 |

Fragaria nubicola Lindl. ex Lacaita |

Rosaceae |

3200 |

Jalkhad |

Katalmewa |

Fruits |

Juice of it is considered as anti diarrhoeal, anti dysenteric. Also used in diabetes and sexual diseases. |

| 38 |

Fritillaria roylei Hook. f. |

Liliaceae |

2950 |

Dadar Nalah |

|

Bulb |

Powder of the dry bulb or in fresh form mixed with butter is used in UTI and to soften and soothe the skin. |

| 39 |

Galium aparine L. |

Rubiaceae |

3110 |

Damdama |

Goose grass |

Whole plant |

Its decoction is used in urinary tract infection. |

| 40 |

Gentiana kurro Royle |

Gentianaceae |

3290 |

Dabukan |

Linkath |

Root |

Powdered root is used in stomach-ache, as tonic and muscles contraction. |

| 41 |

Gentiana moorcroftiana (Wall. ex G. Don) Airy Shaw |

Gentianaceae |

3050 |

Khora |

Bhangara |

Rhizome |

Powder is used to stimulant appetite. |

| 42 |

Gentianodes argentia Omer, Ali & Qaiser |

Gentianaceae |

3300 |

Saifalmaluk mountain |

Linkathi |

Root |

Decoction is used in urinary problems. |

| 43 |

Geranium nepalense Sweet. |

Geraniaceae |

3000 |

Lalazar |

Lijaharri |

Whole plant |

Rhizome’s powder and decoction of aerial parts are used for the treatment of renal infections and as contraction of uterine muscles. |

| 44 |

Geranium wallichianum D. Don ex. Sweet |

Geraniaceae |

2920 |

Barrawae |

Lijaahari/Ratan jog/srazela |

Rhizome |

Boiled powder is used in high blood pressure, uterine diseases and stomach disorders. Also considered as tonic. |

| 45 |

Hyoscyamus niger L. |

Solanaceae |

2730 |

Upper Batakundi |

Khurasani ajwain |

Leaves/seeds |

Decoction extracted from boiled leaves in diluted form is used as sedative, and pain killer. Powders of the seeds are used to treat whooping cough. |

| 46 |

Hypericum perforatum L. |

Hypericaceae |

2540 |

Naran |

Balsana/Shin chae |

Whole plnt |

Tea prepared of young shoots is used in gastric disorders, respiratory and urinary difficulties. Roots powders are used in irregular menstruation. |

| 47 |

Impatiens bicolor Royle |

Balsaminaceae |

2700 |

Lower Batakundi |

Gule mehendi/Atraangey |

Whole plant |

Paste of leaves is used in joint pains. Extract of the plant is regarded as cooling agent and in speeding defecation. |

| 48 |

Indigofera heterantha Wall. ex Brand |

Papilionaceae |

2680 |

Saifulmaluk Nalah |

Kainthi/Ghvareja |

Whole plant |

Powder of the root bark and also is used in hepatitis, whooping cough. Its extract is used as dye for blackening of hairs. |

| 49 |

Inula grandiflora Willd. |

Asteraceae |

2870 |

Upper Batakundi |

Kuth |

Rhizome |

Both powdered and fresh rhizome is used in gastric disorders, in appetite and as diuretic |

| 50 |

Iris hookeriana Foster |

Iridaceae |

3340 |

Besal |

Gandechar |

Rhizome |

Minute amount of powder of dried rhizome is used as speeding defecation and urination and in gall bladder diseases. |

| 51 |

Juglans regia L. |

Juglandaceae |

2450 |

|

Akhor/Ghuz |

Fruits, bark |

Nuts are believed to use as brain tonic, bark in toothache. |

| 52 |

Juniperus communis L. |

Juniperaceae |

3550 |

Such |

Gugarr/Bhentri |

Berries |

Berry powder is considered as enhancer of urination, gas expulsion and stimulant. |

| 53 |

Juniperus excelsa M. Bieb |

Juniperaceae |

3460 |

Getidas |

Gugarr |

Fruits |

Fruits are used as urinary, venereal, uterine and digestive troubles as well as gleets. |

| 54 |

Leucas cephalotes (Roth) Spreng. |

Papilionaceae |

2880 |

Dabukan |

Gomma |

Whole plant |

Extraction of the plant is used to dispel fever and chills and also used in scabies, cough and cold. |

| 55 |

Malva neglecta Wall. |

Malvaceae |

2620 |

Serrian |

Sonchal/Panerak |

Whole plant |

As a local vegetable believed to relinquish bowel and treat dilated veins in swollen anal tissue. |

| 56 |

Mentha longifolia (L.) Hudson. |

Lamiaceae |

2480 |

Upper Batakundi |

Safid Podina |

Whole plant |

Fresh leaves and shoots and also its powder are used in sauces with belief of gas expeller and anti diarrhoeal. |

| 57 |

Mentha royleana Benth. |

Lamiaceae |

2590 |

Batakundi R. Station |

Podina |

Leaves |

Mixed in green teas and are used in vomiting, as cooling agent and gas expeller. |

| 58 |

Nepeta laevigata (D. Don) Hand.-Mazz. |

Lamiaceae |

2910 |

Dadar Nalah |

Deijalbhanga/Peesho butay |

Whole plant |

Powders of the dried plant are used to cure cold, fever and headache. |

| 59 |

Onosma bracteatum Wall. |

Boraginaceae |

2710 |

Jakhad |

Gowzoban |

Whole plant |

Powders are taken with water as heart stimulant while decoction is used as anti dandruff. |

| 60 |

Origanum vulgare L. |

Lamiaceae |

2800 |

Bans |

Jangali majorum |

Whole plant |

Powder mixed with milk is taken in stomach-ache, antispasmodic. Also taken with milk as antimicrobial and flavouring agent. |

| 61 |

Oxyria digyna (L.) Hill. |

Polygonaceae |

2940 |

Khora |

Tarwakay |

Aerial parts |

Young leaves and aerial parts are used as source of vitamin C. |

| 62 |

Oxytropis cachemiriana Camb. |

Papilionaceae |

3120 |

Batakundi |

|

Rhizome |

Rhizome of the plant is traditionally used as a tooth brush to prevent toothache. |

| 63 |

Paeonia emodi Wall. ex Royle |

Paeoniaceae |

2730 |

Naran |

Mamekh |

Seeds & tubers |

Paste prepared from seeds is used in rheumatism. Powdered rhizome is mixed with sweet dishes and used for the treatment of UTI and backache. |

| 64 |

Parnassia nubicola Wall. |

Parnassiaceae |

3110 |

Lalazar |

|

Whole plant |

Whole plant is cooked as a vegetable (pot herb) and is exercised in digestive disorders. |

| 65 |

Pimpinella diversifolia (Wall.) DC |

Apiaceae |

2800 |

Lower Batakundi |

Tarpakhi/Watani kaga |

Whole plant |

Dried plant is crushed to powdered form and used for gas and bowel expulsion. Also used for flavour. |

| 66 |

Pinus wallichiana Jackson |

Pinaceae |

2720 |

Lower Batakundi |

Sraf |

Resin, woods |

Resin is considered as diaphoretic, also applied to the cracked (wounded) heels. |

| 67 |

Plantago himalaica Pilger |

Plantaginaceae |

3230 |

Barrawae |

Jabae |

Leaves |

Paste prepare from fresh leaves is used in skin problems especially soured feet. |

| 68 |

Plantago lanceolata L. |

Plantaginaceae |

2950 |

Upper Batakundi |

Ispeghol/Jabae |

Leave/ seeds |

Decoction of boiled leaves is used in respiratory problems. Seeds are taken with milk to ease digestion. |

| 69 |

Plantago major L. |

Plantaginaceae |

3000 |

Dabukan |

Ipeghol/Jabae |

Root, seeds, leaves |

Leaves are cooked and taken orally to cure seasonal fevers. Chopped leaves are used as poultice to cure wounds. Seeds are considered as tonic. Root decoction & infusion is taken as anti dysenteric and leaves decoction in breathing problems. |

| 70 |

Podophllum hexandrum Royle |

Podophyllaceae |

3080 |

Khora |

Kakorra/Gangorra/ |

Rhizome & Fruits |

A poisonous plant but expert healers use it in a minute amount in mixture with other plants. Its fruit is used to ease bowel movement whilst rhizome is used in the treatment of cancer. |

| 71 |

Polygonum aviculare L. |

Polygonaceae |

2940 |

Damdama |

Bandakey |

Whole plant |

Aerial parts of the plant are cooked as pot herb and considered as purgative and emetic |

| 72 |

Polygonum plebeium R. Br |

Polygonaceae |

3440 |

Such |

Baramol/Noorealam |

Root |

Root is boiled and mixed with butter locally for stimulate mammary glands; It is also considered to soothes and protects the alimentary canal. |

| 73 |

Potentilla anserina L. |

Rosaceae |

2820 |

Lalazar |

Spangji |

Whole plant |

Whole plant is used as anti-diarrhoeal and also in intestinal infections |

| 74 |

Primula denticulata Smith |

Primulaceae |

3220 |

Serrian |

Mamera |

Rhizome |

Powdered rhizome mixed with honey is used to cure various eyes disorders. |

| 75 |

Prunella vulgaris L. |

Lamiaceae |

2910 |

Upper Batakundi |

Ustakhdus |

Whole plant |

Whole plant both in fresh and dry form is used to relieve respiratory difficulties, in treating joint pains and easing gastric spasm. |

| 76 |

Prunus cerasoides D. Don |

Rosaceae |

2670 |

Such |

Alubaloo |

Bark, fruit |

Decoction of the bark is taken in biting and fruit as nerve tonic |

| 77 |

Rheum austral D. Don |

Polygonaceae |

3450 |

Saifalmaluk |

Chotial |

Rhizome & shoots |

Leaves and shoots are used as salad for to normalize irregular heart beating, respiratory problems, sore eyes and body strength. Rhizome is cooked and used as wound healing agent and to relive urinary tract disorders. |

| 78 |

Rhododendron hypenanthum Balf.f |

Oleaceae |

3610 |

Lalazar peak |

Tazak Tusum/Gul namer |

Leaves |

Fresh leaves of it are used in spices as flavouring agent. |

| 79 |

Ribes alpestre Decne |

Grassullariaceae |

2720 |

Batakundi R. Station |

|

Berries |

Berry fruits are considered as heart tonic. |

| 80 |

Rosa webbiana Wall. ex Royle |

Rosaceae |

2900 |

Besal |

Jangali Gulab |

Flowerss, bark |

Processed flowers (Arq) are used in respiratory problems while bark is used in wounds healing as well as flavour. |

| 81 |

Rubus sanctus Schreber |

Rosaceae |

3000 |

Khora |

Alish |

Whole plant |

Fruit is laxative and dysentery; Infusion of leaves and young shoots is used in whooping cough. |

| 82 |

Rumex dentatus L. |

Polygonaceae |

2540 |

Lalazar |

Shalkhey |

Roots & leaves |

Root powder is considered to overcome dryness and scaling of the skin. |

| 83 |

Rumex nepalensis Sprenge |

Polygonaceae |

2670 |

Lower Batakundi |

Ambavati |

Roots & leaves |

Leaves are used as substitute of Rheum austral whilst its root is believed to ease bowel evacuation. |

| 84 |

Salvia lanata Roxb. |

Lamiaceae |

2870 |

Such |

Kiyan |

Whole plant |

Aerial parts are used as vegetable and its root powders are considered to ease bowel evacuation; also used in cough & cold. |

| 85 |

Salvia moorcroftiana Wallich ex Benth |

Lamiaceae |

2910 |

Damdama |

Kalizarri |

Leaves, seeds, roots |

Fresh leaves are put in hot ash for a while and then used as poultice for abscesses. Cooked leaves are used in dysentery and colic. |

| 86 |

Sambucus weightiana Wall. ex Wight & Arn |

Sambucaceae |

2460 |

Barrawae |

Mushkiara |

Whole plant |

Decoction and powder is used to relieve respiratory difficulties and inflammatory skin conditions. |

| 87 |

Saussurea albescens Hook. f. & Thoms |

Asteraceae |

3000 |

Serrian |

Kuth |

Roots |

Roots are cooked in local butters and used as tonic, also use in treatment of stomach as well as pain, and skin diseases. |

| 88 |

Silene vulgaris Garck |

Caryophyllaceae |

2780 |

Dabukan |

Barra takla |

Whole plant |

Juice of it is used as digestive, in eye diseases, and is also vaporized to kill or repel pests. |

| 89 |

Swertia ciliata (D. Don ex G. Don) B. L. Burtt |

Gentianaceae |

2850 |

Bans |

Chirita |

Whole plant |

Powders are used in irregularity or infrequency of passing faeces as well as stomach burn. |

| 90 |

Sysimbrium irio L. |

Brassicaceae |

2940 |

Jalkhad |

Khubkalan |

Leaves & seeds |

Seeds are used in throat & chest infection & ease breathing; Paste of leaves is applied to cure sunburn & enhance skin beauty |

| 91 |

Taraxacum officinale Weber |

Asteraceae |

2720 |

Naran |

Hand/Gulsag/Booda boodae |

Roots |

Roots decoction is taken to ease urination and other kidney disorders whilst powders are taken as tonic. |

| 92 |

Thymus linearis Benth. |

Lamiaceae |

3240 |

Besal |

Bazori/Sperkae/Ban ajwain |

Whole plant |

Plant is used to make tea, drink, juice to cure stomach & liver complaints; Powder of aerial parts is used in cough. |

| 93 |

Trifolium repens L. |

Papilionaceae |

2610 |

Dabukan |

Chapatra |

Whole plant |

Fresh plant is used as worms expulsion (Cattles poison) |

| 94 |

Trillidium govanianum (Wall. ex D. Don) Kunth |

Trilliaceae |

3370 |

Saifalmaluk Lake |

Tandhi jarri |

Roots |

Powdered plant is used as body and sexual tonic. |

| 95 |

Tussilago farfara L. |

Asteraceae |

2990 |

Batakundi Hills |

Funjiwam |

Whole plant |

Aerial parts are cooked and used in respiratory infections. |

| 96 |

Ulmus wallichiana Planch. |

Ulmaceae |

2580 |

Damdama Nalah |

Kahey |

Bark |

Considered highly medicinal for digestive tract diseases. |

| 97 |

Valeriana pyrolifolia Decne |

Valerianaceae |

3460 |

Lalazar Peak |

Mushkbala/Shangeetae |

Rhizome |

Powdered rhizome is used to treat spasm and habitual constipation. |

| 98 |

Verbascum thapsus L. |

Scrophulariaceae |

2980 |

Naran |

Kharghvag/Jangali tamakoo |

Whole plant |

Root’s powder is considered as aphrodisiac; leaves, paste is used in skin problems; leaves are also smoked to induce sedation by reducing irritability or excitement. |

| 99 |

Viburnum cotinifolium D. Don |

Caprifoliaceae |

2630 |

Naran |

Taliana |

Fruits |

Fruits are taken for reducing uterine irritability and stopping bleeding usually by female |

| 100 |

Viburnum grandiflorum Wall. ex DC. |

Caprifoliaceae |

2680 |

Naran |

Guch |

Fruits |

Fruits are used to ease gastric spasms and uterine irritability. |

| 101 | Viola canescens Wall. ex Roxb. | Violaceae | 3020 | Jalkhad | Gule banafsha | Whole plant | Young shoots are used to promote circulation, dispels fever and chills, relieves muscle tension whilst decoction & infusion is used in sore throat. |

Plants’ parts used and their preparation

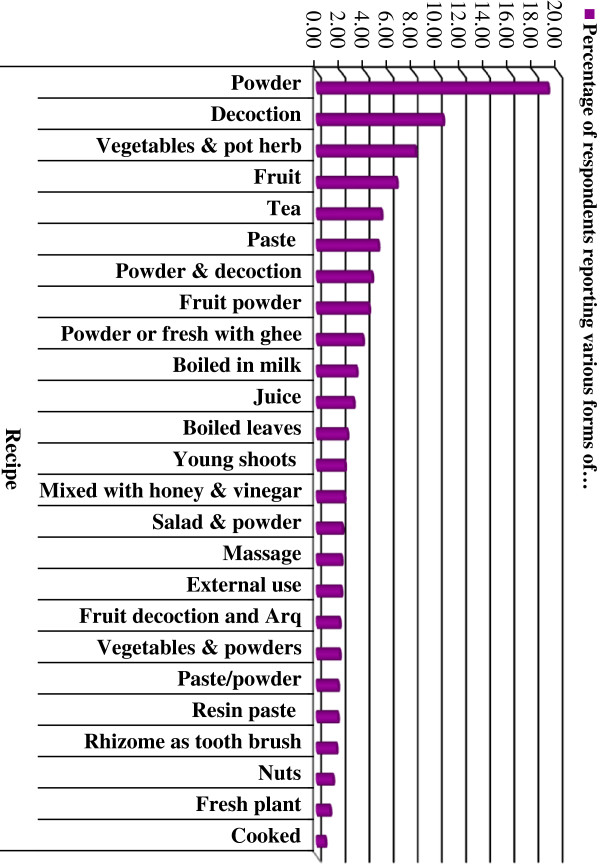

The interview results indicate that whole plants are used in 54% of treatments followed by rhizomes (21%), fruits (9.5%) and roots (5.5%). Bark, flowers and seeds were used less frequently. Most of the plants used are hemi-cryptophytes and geophytes and fewer are woody (phanerophytes and chamaephytes) or therophytes (Figure 3). Whole plants or plant parts are utilized in various forms in traditional herbal recipes. In the majority of recipes, they are in the form of powder (19%) followed by decoction + infusion (10.5%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Parts of plant used for medicinal purposes.

Figure 4.

Recipes for medicinal plants reported by interviewees (%).

Therapeutic uses

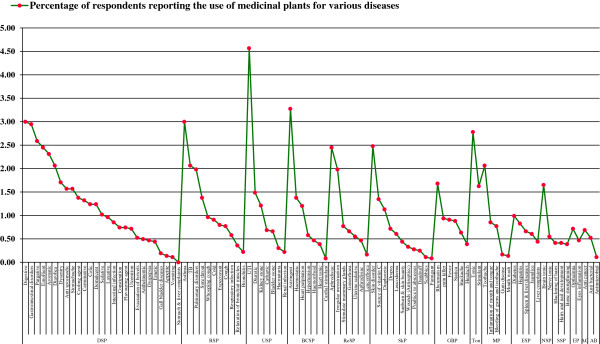

The results of the questionnaires analysis reveal 97 prominent remedial uses of medicinal plants, which were divided into 15 major categories based on the ailment of a specific human system, being treated with. The largest number of ailments cured with medicinal plants are associated with the digestive system (32.76% responses) followed by those associated with the respiratory and urinary systems (13.72% and 9.13% respectively). The percentage of ailments associated with the blood circulatory and reproductive systems and the skin were 7.37%, 7.04% and 7.03%, respectively. In terms of a single problem of a specific system, the urinary tract infection (UTI) was mentioned on top; treated with medicinal plants followed by asthma and gastric problems. The other diseases related with general body, endocrine system, nervous system, mouth and eyes etc. were considered each by 5% or less than 5% respondents. Figure 5 and 6 visualise the results of the specific diseases of the human system cured with medicinal plants as mentioned by interviewees, whilst a detailed summary of the species along with a list of the specific diseases is presented in Table 2.

Figure 5.

Medicinal use categories mentioned by respondents for the treatment of different categories of disease or other ailments.

Figure 6.

Medicinal plant uses for treating different diseases & ailments. DSP = Digestive System’s Problems; RSP = Respiratory System’s Problems; USP = Urinary System’s Problems; BCSP = Blood Circulatory System’s Problems; ReSP = Reproductive System’s Problems; SkP = Skin Problems; GBP = General Body Problems; Ton = Tonic; MP = Mouth Problems; ESP = Endocrine System Problems; NSP = Nervous System’s Problem; SSP = Skeleton System’s problems; EP = Eyes problems; AC = Anti Cancer AB = Antibacterial.

Discussion

Role of native plants in supporting human livelihoods and well being

Findings of this paper signify the relationship between the provisioning ecosystem services of vegetation and human well-being in the study area. The questionnaire analyses indicate that the people of the Naran Valley possess valuable knowledge of natural plant biodiversity and the services it can provide are immensely important to them. There was a variation in knowledge at individual level depending upon the relation between the person and the specific plants species or group which he/she prioritizes for certain uses which is reported in number of other studies also [29,30]. Nevertheless, this study has been able to demonstrate that plants are used to support a wide range of livelihood activities in the study area, and particularly as a source of traditional medicines. Furthermore, plant biodiversity of the region provide timber, fuel, medicines, food, fodder, grazing and others services to the indigenous communities. However extensive uses of natural vegetation in the past have decreased the provisioning services. Local residents especially the older generation prefer to live in the valley because of the existing provisioning ecosystem services and their traditional ethno-ecological knowledge. However, the new generation tend to leave those rural spaces in search of education, facilities and easy modern life [31].

Medicinal plant resources

The use of plants to cure diseases is as old as human history. Around 20% of the plant species of the world are estimated to be used in health care systems [32]. Medicinal plants play an important role in the traditional health care systems of this region also. A few of the species found in the region, i.e. Dioscorea deltoidea, Podophyllum hexandrum, Berberis pseudoumbellata, Cypripedium cordigerum and Dactylorhiza hatagirea, are listed on the CITES appendix II (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). One or more of these species were also reported in few other studies from other Himalayan and the Hindu Kush areas [17,33]. Some other medicinal species are endemic to the Himalayas and hence should also be given attention in order to ensure sustainable use e.g., Cedrus deodara and Aesculus indica, whilst some are rare in the region e.g., Aconitum heterophyllum, Aconitum violaceum, Ephedra gerardiana, Hypericum perforatum, Indigofera heterantha, Paeonia emodi, and Ulmus wallichiana. In addition to medicinal uses, these species provide other services like timber fuel and grazing etc. Numbers of the remote valleys in the Himalayas have not been studied specifically for the ecosystem services and plant medicinal uses though indigenous inhabitants of these areas have a long established system of health care and cure with available medicinal plant resources. The elder people have more accurate knowledge about the parts and recipes than the young which improve the effectiveness of medicinal plants. Similar trend was also reported by other ethnobotanists in the Southern Ethiopia and Hindu Kush region [34,35]. It is important to recognise that unsustainable collection of medicinal plants is one of the main causes of plant population decline. Increasing human population, extensive grazing, habitats losses, multipurpose collection and carelessness are the other factors. All such ecological as well as cultural matters need to be documented and addressed while designing management, preservation and conservation strategies. Results of this paper also demonstrate that most of the plants are either used as a whole or its parts like roots and rhizomes distinctively which are also alarming signals against the sustainable use of this highly valued plant biodiversity. In addition marketing of certain species indicate probable threats information about their conservation which also suggests that number of these economically important species can be domesticated and propagated in protected places for marketing purposes. Interestingly, most of the less abundant species and families are utilized frequently by the locals. For example, 31 small families with only 1 or 2 species are all used medicinally in the area. These findings not only prove that peoples utilize the plants according to their traditional knowledge and not their abundance but also indicate the rarity of such taxa in the near future.

Indigenous knowledge as a cultural asset

Rapid technological and economic development has brought ecological and social changes all over the world. Cultural changes even take place in remote rural societies due to their increasing interactions with modern urban cities. Subsequently, knowledge about the use of plant resources, as well as the plant wealth itself, is declining in a number of regions [36,37]. The present study also reveals a decrease in indigenous knowledge and changes in attitudes regarding health-giving flora among the younger generation. This phenomenon is confirmed from the study of [38] on the Pakistani migrants in Bradford UK. This and other similar studies, further communicate the extinction of traditional knowledge in modern societies. Indigenous people, although the possessor of traditional knowledge have no proper training in sustainable ways of plant collection, post collection care and processing and usually waste a considerable amount of medicinal plants. Such sort of unwise practices over a long time can cause a reduction in plant biodiversity in general and of plant species providing provisioning services in particular [39,40]. It is therefore, suggested to recruit ethno-ecologists and experts to train the local people for the sustainable utilization of medicinal plant resources. Some of the problems associated with medicinal plant resources can be overcome through research on domestic growth of medicinal plants and development of processing techniques among the people. In this recent millennium, present and number of other research studies suggest urgent call for the preservation of both long-established remedial knowledge and medicinal plant resources in the developing world, particularly in the Himalayas [17,41-44]. Furthermore, long-established knowledge about the medicinal values of plants has contributed a lot in the past in production and synthesis of synthetic drugs and market values. It has played and still plays a remarkable role in solving health related problems especially in undeveloped and remote parts of the world. A number of issues were identified during the present project. These include documentation of the traditional knowledge; intellectual property rights of the locals, trainings about the sustainable use of the available resources and use of the traditional knowledge for conservation which can be addressed in the future.

Competing interests

SMK involved in formulating study design, questionnaire, field work, data collection and compilation of 1st draft of this paper. SP, HA and DMH planned questionnaire and supervised the project. HS gathered relevant literature. ZU identified most of the plant species in the field. MA processed and preserved the herbarium specimens. All the authors have read and approved the final submission of the paper.

Authors’ contributions

The authors articulate that they have no competing interest.

Contributor Information

Shujaul M Khan, Email: shuja60@gmail.com.

Sue Page, Email: sep5@leicester.ac.uk.

Habib Ahmad, Email: drhahmad@gmail.com.

Hamayun Shaheen, Email: hamayunmaldial@yahoo.com.

Zahid Ullah, Email: zahidmatta@gmail.com.

Mushtaq Ahmad, Email: mushtaq@qau.edu.pk.

David M Harper, Email: david.m.harper@ntlworld.com.

Acknowledgements

Inhabitants of the Naran Valley are highly acknowledged for participation in interviews and sharing their ethnomedicinal knowledge.

References

- Butler CD, Oluoch-Kosura W. Linking future ecosystem services and future human well-being. Ecology and Society. 2006;11(1):30. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss1/art30/ [Google Scholar]

- Seppelt R, Dormann CF, Eppink FV, Lautenbach S, Schmidt S. A quantitative review of ecosystem service studies: Approaches, shortcomings and the road ahead. J Appl Ecol. 2011;48(3):630–636. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2010.01952.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) Ecosystems and human well-being: a framework for assessment Millennium ecosystem assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney HA, Cropper A, Reid W. The millennium ecosystem assessment: What is it all about? Trends Ecol Evol. 2004;19(5):221–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter SR, DeFries R, Dietz T, Mooney HA, Polasky S, Reid WV, Scholes RJ. Millennium ecosystem assessment: Research needs. Science. 2006;314(5797):257–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1131946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan SJ, Hayes SE, Yoskowitz D, Smith LM, Summers JK, Russell M, Benson WH. Accounting for natural resources and environmental sustainability: Linking ecosystem services to human well-being. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44(5):1530–1536. doi: 10.1021/es902597u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol Econ. 2002;41(3):393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J, Banzhaf S. What are ecosystem services? The need for standardized environmental accounting units. Ecol Econ. 2007;63(2–3):616–626. [Google Scholar]

- Gamfeldt L, Hillebrand H, Jonsson PR. Multiple functions increase the importance of biodiversity for overall ecosystem functioning. Ecology. 2008;89(5):1223–1231. doi: 10.1890/06-2091.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira E, Queiroz C, Pereira HM, Vicente L. Ecosystem services and human well-being: A participatory study in a mountain community in Portugal. Ecology and Society. 2005;10(2):231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Zobel M, Öpik M, Moora M, Pärtel M. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: It is time for dispersal experiments. J Veg Sci. 2006;17(4):543–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1654-1103.2006.tb02477.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Page S, Ahmad H, Shaheen H, Harper DM. Vegetation dynamics in the Western Himalayas, diversity indices and climate change. Sci., Tech. and Dev. 2012;31(3):232–243. [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C. Managing ecosystem services: What do we need to know about their ecology? Ecol Lett. 2005;8(5):468–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Khan MA, Rashid U, Zafar M, Arshad M, Sultana S. Quality assurance of herbal drug valerian by chemotaxonomic markers. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8(6):1148–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Khan MA, Zafar M, Arshad M, Sultana S, Abbasi BH, Siraj-Ud D. Use of chemotaxonomic markers for misidentified medicinal plants used in traditional medicines. J Med Plant Res. 2010;4(13):1244–1252. [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Harper DM, Page S, Ahmad H. Residual value analyses of the medicinal flora of the Western Himalayas: the Naran Valley, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany. 2011;43:SI-97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad H, Khan SM, Ghafoor S, Ali N. Ethnobotanical study of upper siran. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2009;15(1):86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shinwari ZK, Gilani SS. Sustainable harvest of medicinal plants at Bulashbar Nullah, Astore (Northern Pakistan) J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84(2–3):289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh KN, Lal B. Ethnomedicines used against four common ailments by the tribal communities of Lahaul-Spiti in western Himalaya. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;115(1):147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SI, Qaiser M. A Phyto-Geographical analysis of the Phenerogames of Pakistan and Kashmir. Proc. R. Soc. Edinburgh. 1986;89:89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Harper DM, Page S, Ahmad H. Species and community diversity of vascular Flora along environmental gradient in Naran Valley: A multivariate approach through indicator species analysis. Pakistan J Bot. 2011;43(5):2337–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM. Plant communities and vegetation ecosystem services in the Naran Valley, Western Himalaya. University of Leicester; 2012. (PhD Thesis). [Google Scholar]

- Da Cunha LVFC, De Albuquerque UP. Quantitative ethnobotany in an Atlantic Forest fragment of Northeastern Brazil - Implications to conservation. Environ Monit Assess. 2006;114(1–3):1–25. doi: 10.1007/s10661-006-1074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GJ. Ethnobotany; A methods manual: WWF and IIED. London: Routledge: Earth scans Camden; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AB. Applied Ethnobotany; people, wild plant use and conservation: London and Sterling. London and Sterling, VA: Earth scan publication limited; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kassam K, Karamkhudoeva M, Ruelle M, Baumflek M. Medicinal plant use and health sovereignty: findings from the Tajik and Afghan Pamirs. Hum Ecol. 2011;38(6):817–829. doi: 10.1007/s10745-010-9356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MSH, Koike M. Towards exploration of plant-based ethno-medicinal knowledge of rural community: Basis for biodiversity conservation in Bangladesh. New Forests. 2010;40(2):243–260. doi: 10.1007/s11056-010-9197-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uprety Y, Poudel RC, Asselin H, Boon E. Plant biodiversity and ethnobotany inside the projected impact area of the Upper Seti Hydropower Project, Western Nepal. Environ Dev Sustainability. 2010;13(3):463–492. [Google Scholar]

- Quijas S, Schmid B, Balvanera P. Plant diversity enhances provision of ecosystem services: A new synthesis. Basic Appl Ecol. 2010;11(7):582–593. doi: 10.1016/j.baae.2010.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza R. Ecosystem services: multiple classification systems are needed. Biol Conserv. 2008;141(2):350–352. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2007.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giam X, Bradshaw CJA, Tan HTW, Sodhi NS. Future habitat loss and the conservation of plant biodiversity. Biol Conserv. 2010;143(7):1594–1602. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie JEM. IUCN Red List Of Threatened Species. A Global Species Assessment. 2004. IUCN-SSC http://www.fauna-dv.ru/publik/Baillie%20et%20al_2004_book.pdf.

- Khan SM, Ahmad H, Ramzan M, Jan MM. Ethno-medicinal plant resources of Shawar Valley. Pakistan J Bio Sci. 2007;10:1743–1746. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.1743.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balemie K, Kebebew F. Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Derashe and Kucha Districts, South Ethiopia. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine. 2006;2 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Zeb A, Ahmad H. Medicinal Plants and Mountains: Long-Established Knowledge in the Indigenous People of Hindu Kush. Germany: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bussmann RW, Sharon D. Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: Tracking two thousand years of healing culture. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine. 2006;2 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavaleta ES, Hulvey KB. Realistic species losses disproportionately reduce grassland resistance to biological invaders. Science. 2004;306(5699):1175–1177. doi: 10.1126/science.1102643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni A, Houlihan L, Ansari N, Hussain B, Aslam S. Medicinal perceptions of vegetables traditionally consumed by South-Asian migrants living in Bradford, Northern England. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;113(1):100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim SE, Cullen LC, Smith DJ, Pretty J. Ecological knowledge is lost in wealthier communities and countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(4):1004–1009. doi: 10.1021/es070837v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes AL, Brown AD, Grau HR, Grau A. Local knowledge and the use of plants in rural communities in the montane forests of northwestern Argentina. Mount Res Dev. 1997;17(3):263–271. doi: 10.2307/3673853. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SD, Walker DJ, Hall SA, Burke KC, Shah MT, Stockli L. Did the Kohistan-Ladakh island arc collide first with India? Bull Geol Soc Am. 2009;121(3–4):366–384. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen H, Ullah Z, Khan SM, Harper DM. Species composition and community structure of western Himalayan moist temperate forests in Kashmir. Forest Ecol Manag. 2012;278:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Page S, Ahmad H, Harper DM. Anthropogenic influences on the natural ecosystem of the Naran Valley in the Western Himalayas Pakistan. Pakistan J Bot. 2012;44(SI 2):231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Page S, Ahmad H, Harper DM. Identifying plant species and communities across environmental gradients in the Western Himalayas: Method development and conservation use. J Ecol Inform. 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2012.11.010.