Abstract

Background

Few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of massage for back pain.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of two types of massage for chronic back pain.

Design

Single-blind parallel group randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Integrated health care delivery system in Seattle area.

Patients

401 persons 20 to 65 years of age with non-specific chronic low back pain.

Interventions

Ten treatments over 10 weeks of Structural Massage (intended to identify and alleviate musculoskeletal contributors to pain through focused soft-tissue manipulation) (n=132) or Relaxation Massage (intended to decrease pain and dysfunction by inducing relaxation) (n=136). Treatments provided by 27 experienced licensed massage therapists. Comparison group received continued usual care (n=133). Study presented as comparison of usual care with two types of massage.

Measurements

Primary outcomes were the Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) and the Symptom Bothersomeness scale measured at 10 weeks. Outcomes also measured after 26 and 52 weeks.

Results

At 10 weeks, the massage groups had similar functional outcomes that were superior to those for usual care. The adjusted mean RDQ scores were 2.9 and 2.4 points lower for the relaxation and structural massage groups, respectively, compared to usual care (95% CIs: [1.8, 4.0] and [1.4, 3.5]). Adjusted mean symptom bothersomeness scores were 1.7 points and 1.4 points lower with relaxation and structural massage, respectively, versus usual care (95% CIs: [1.2, 2.2] and [0.8, 1.9]). The beneficial effects of relaxation massage on function (but not on symptom reduction) persisted at 52 weeks, but were small.

Limitations

Restricted to single site; therapists and patients not blinded to treatment.

Conclusions

This study confirms the results of smaller trials that massage is an effective treatment for chronic back pain with benefits lasting at least 6 months, and also finds no evidence of a clinically-meaningful difference in the effectiveness of two distinct types of massage.

Primary Funding Source

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Massage has become one of the most popular complementary and alternative medical therapies for back pain [1]. Furthermore, back and neck pain represent over one third [2] of the more than 100 million annual visits to massage therapists [3]. In the U.S., massage incorporates various soft-tissue techniques and sometimes techniques aimed at changing how patients perceive and use their bodies. Virtually all massage schools teach Swedish massage techniques aimed at relaxation, but only a minority of therapists take courses in techniques for treating back pain.

Recent reviews found limited evidence massage is an effective treatment for chronic back pain [4, 5]. No studies compared the effectiveness of widely available relaxation massage with structural massage, which focuses on correcting soft tissue abnormalities.

Study aims were to determine if relaxation massage reduces pain and improves function in patients with chronic low back pain, and compare the effectiveness of relaxation massage and structural massage.

METHODS

Design Overview

This study was approved by the Group Health institutional review board. Participants gave written informed consent. Study details are described elsewhere [6].

Setting and Participants

Between August 2006 and April 2008 we invited participation through advertisements in our health plan’s magazine and mailings to plan members 20 to 65 years old with outpatient visit diagnoses suggesting non-specific chronic low back pain. Invitation letters were mailed 3 to 12 months after these visits. Study staff phoned respondents to determine eligibility--- low back pain lasting at least three months without 2 or more pain-free weeks and pain bothersomeness rated at least 3 on a 0 to 10 scale. Those eligible were administered a baseline questionnaire and randomized to treatment. Exclusion criteria were: 1) specific causes of back pain (e.g., cancer, fractures, spinal stenosis), 2) complicated back problems (e.g., sciatica, prior back surgery in past 3 years, medicolegal issues), 3) conditions making treatment difficult (e.g., paralysis, psychoses), 4) conditions that might confound treatment effects or interpretation of results (e.g., severe fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis), 5) inability to speak English, 6) massage within past year, or 7) plans to visit provider for back pain.

Randomization and Interventions

Randomization, blocked on therapist, was done using a concealed and protected centrally-generated variable-sized block design created by the biostatistician. One third of participants were randomized to each arm: Usual Care, Relaxation Massage, and Structural Massage. Therapists were not blinded to type of massage they provided. Participants knew if they received massage but were blinded to type.

Study Treatments

Massage was provided by 27 licensed therapists with at least 5 years experience, comfort following protocols, and experience in the permitted techniques. Therapists received 1.5 days of protocol training [6]. Treatment fidelity was promoted by monitoring treatment forms completed by therapists at each visit coupled with corrective feedback and a mid-study meeting.

Both massage techniques were provided in therapists’ offices at no cost. Both massage protocols prescribed 10 weekly treatments, with first visits lasting 75 to 90 minutes and follow-up visits 50 to 60 minutes. We defined adherence as completion of at least 8 visits. At each visit, therapists could recommend up to three home exercises from a pre-defined list of seven exercises, six of which were common to both treatments [6].

Relaxation Massage, intended to induce a generalized sense of relaxation, permitted effleurage, petrissage, circular friction, vibration, rocking and jostling, and holding. Therapists were given time parameters for each body region, including 7-20 minutes on back and buttocks [6]. Therapists could provide a 2.5-minute relaxation exercise CD as home exercise to enhance and prolong treatment benefits.

Structural Massage, intended to identify and alleviate musculoskeletal contributors to back pain, allowed myofascial, neuromuscular, and other soft tissue techniques [6]. Myofascial techniques are intended to engage and release identified restrictions within myofascial tissues. Neuromuscular techniques are used to resolve soft tissue abnormalities by mobilizing restricted joints, lengthening constricted muscles and fascia, balancing agonist/antagonist muscles, and reducing hypertonicity. Areas of the body treated varied across patients and treatment sessions. Therapists could recommend a psoas stretch home exercise to enhance and prolong any benefits of structural massage.

Usual care participants received no special care but were paid $50. Actual care was determined from medical records and interviews.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Outcomes were measured at baseline and after 10, 26 and 52 weeks by interviewers masked to treatment. Pre-specified primary outcomes were back-related dysfunction and symptoms assessed at 10-weeks, immediately after treatment completion.

Dysfunction was measured using the modified Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ), a reliable, valid and sensitive measure with substantial construct validity [7, 8]. A between-group difference in improvement in mean values of at least 2.0 points on this 0 to 23 scale was considered clinically meaningful [8,9].

Participants were asked to rate the bothersomeness of their pain during the past week from 0 (“not at all”) to 10 (“extremely”). A between-group difference in improvement in mean values of at least 1.5 points was considered clinically meaningful [8,9].

Secondary outcomes included: 1) 26- and 52-week measures of the primary outcomes, 2) percentage of participants with pre-specified clinically meaningful reductions in dysfunction (3+ point decrease on the RDQ scale) and symptoms (2+ point decrease in symptom bothersomeness), 3) physical and mental health Short Form Health Survey 12 component summary scores [10], 4) self-reported medication use for back pain in prior week, 5) days spent in bed, home from work or school, or cutting down on usual activities due to back problem during past week [11], 6) global improvement in back-related dysfunction rated on a seven point scale from “completely gone” to “much worse”, 7) feelings if spent rest of life with back pain experienced in past week (7-point scale ranging from “delighted” to “terrible”), 8) satisfaction with back care using a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied), and 9) total costs of back pain-related visits, imaging studies, and medications during follow-up year from electronic medical records. Visits not covered by the health plan were identified from interviews.

Finally, participants were asked open-ended questions about adverse experiences on the 10-week interview and at each massage visit.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size and the detectable difference

Sample size calculations were conducted to ensure adequate power at 10-weeks to detect a clinically meaningful two point mean difference between the Structural Massage and Usual Care groups on the RDQ Scale, assuming the Structural Massage group would be one-point better than the Relaxation Massage group. Assuming 10% loss to follow-up and standard deviations from our pilot study of 92 participants (RDQ SD = 4.65 and Bothersomeness SD = 2.71), our target sample was 399 individuals (133 per group). This provided 85% power to detect a significant difference in the three treatment groups using an omnibus Wald test, and 91% power to detect a pairwise difference of two points on the RDQ, and for the bothersomeness outcome, >99% power for the difference among the three treatment groups and 99% power to detect a pairwise difference of 1.5 points.

Analysis

Analyses were conducted using the original randomized treatment assignment regardless of protocol adherence. Analyses were conducted using regression through generalized estimating equations [12] with an independent working correlation structure and robust standard error estimates taking into account multiple outcomes per participant. Follow-up times were treated as categorical variables using dummy variables for each treatment, each time point, and all two-way interactions between follow-up time and treatment. Adjusted models included baseline covariates that were either pre-specified, imbalanced at baseline (i.e. potential confounders) and/or associated with a primary outcome (i.e. precision variables)--age, group, sex, baseline RDQ and bothersomeness score, education level, body mass index, type of work, original cause of back pain, >7 days of reduced activities due to back pain and medication use in prior week. We pre-specified the adjusted analysis as the primary analysis. For continuous and binary outcome measures we applied linear and modified Poisson regression, respectively, with robust standard errors. Modified Poisson regression allows estimation of relative risks for non-rare outcomes using Poisson regression and corrects the misspecification of the variance using robust standard errors in a generalized estimating equation framework [13].

To control for multiple comparisons we utilized the least significant difference approach, evaluating pairwise treatment comparisons at a given time only if the overall omnibus test was statistically significant at the 0.05-level. Mean differences, 95% confidence intervals, and omnibus p-values for treatment group effect and pairwise significance are presented.

To assess effects of individual providers on the RDQ outcome, we fit an adjusted mixed effects model with a random intercept for each provider using only data from the two massage arms. The intra-class correlation coefficient was calculated to quantify degree of variability due to providers relative to overall variability of the outcome.

Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina)and used two-sided p-values.

Missing Data

The proportion of missing data for the primary outcome measures was 5% at 10, 7% at 26, and 9% at 52 weeks. We used Stata Statistical Software version 10.1 (StataCorp 2007, College Station, TX) [14] to perform multiple imputation by chained equations to account for missingness. We imputed both missing outcomes and baseline covariates. Estimates from each imputed dataset were combined following rules outlined by Rubin [15, 16]. Imputed analysis did not yield appreciable differences from the unadjusted and adjusted complete-case analyses (results not shown).

RESULTS

Study Recruitment and Follow-up

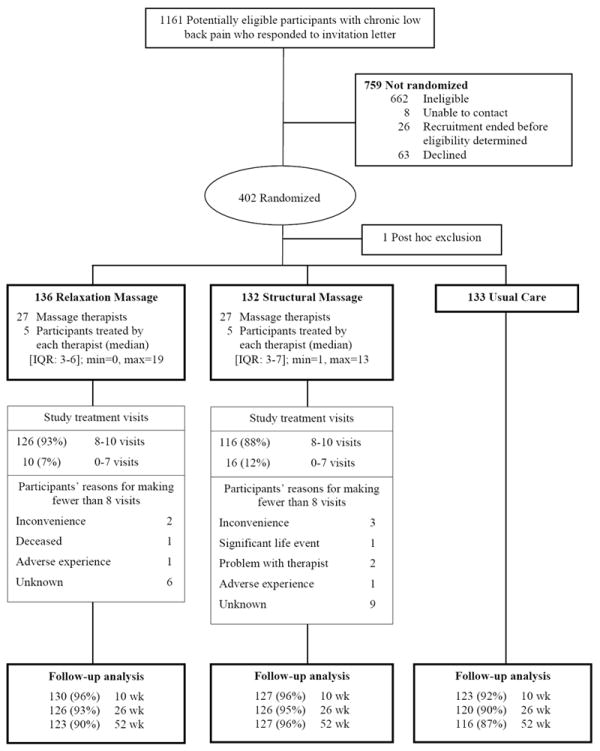

We mailed 9,127 invitations and evaluated 1161 responses; 402 (35%) were eligible and randomized (Figure 1). Main ineligibility reasons were massage in previous year (22%), less than 3 months of back pain (20%), sciatica (14%), medical contraindications (12%), and planned visits for back pain (10%). One participant with an abdominal aortic aneurysm was excluded post-randomization. Analyses included 401 participants randomized to Relaxation Massage (n=136), Structural Massage (n=132), or Usual Care (n=133). Follow-up was 95% at 10 weeks, 93% at 26 weeks, and 91% at 52 weeks. Interviewers reported treatment group (massage or Usual Care) had been revealed to them by fewer than 10% of participants.

Figure 1.

Study Participant Flow Diagram.

Baseline Characteristics

Participants were mostly middle aged, female, and white; 51% were college graduates (Table 1). Mean scores of 10.8 on the RDQ and 5.7 for symptom bothersomeness indicated moderately severe back problems. Participants assigned to Relaxation Massage had greater dysfunction (RDQ score over 1 point higher) but there were no other clinically or statistically significant between-group baseline differences.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 401 Participants with Chronic Low Back Pain (LBP) by Treatment Group

| Treatment Group

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Massage | Relaxation Massage | Usual Care | |

| Participant Characteristics | n = 132 | n = 136 | n=133 |

| Female, % | 66 | 65 | 62 |

| White, % | 86 | 87 | 86 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 46 (12) | 47 (11) | 48 (11) |

| Body Mass Index, mean (SD) | 29 (7) | 28 (6) | 29 (6) |

| Married, % | 74 | 71 | 74 |

| Education: Completed at least some college, % | 51 | 53 | 49 |

| Annual household income <$45,000 (%) | 31 | 26 | 30 |

| Physical demands of job | |||

| Not employed, % | 13 | 21 | 17 |

| Work is mainly sedentary, % | 37 | 36 | 42 |

| Work requires lifting up to 20 lbs, % | 21 | 13 | 17 |

| Work requires lifting >20 lbs, % | 29 | 29 | 23 |

| SF-12 physical health scale score, mean (SD) | 40 (9) | 38 (8) | 39 (8) |

| SF-12 mental health scale score, mean (SD) | 50 (9) | 50 (10) | 50 (9) |

| Back Pain Characteristics | |||

| Original cause of LBP not known, % | 23 | 13 | 14 |

| LBP for at least 1 y, % | 77 | 72 | 78 |

| LBP d in past 6 mo, mean (SD) | 133 (51) | 128 (50) | 131 (55) |

| Pain below knee, % | 11 | 15 | 19 |

| RDQ score (0-23 scale), mean (SD) | 10.1 (5.0) | 11.6 (5.0) | 10.5 (5.3) |

| LBP bothersomeness in past wk (0-10 scale), mean (SD) | 5.6 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.8) | 5.8 (1.6) |

| Any medication use in past wk for LBP, % | 68 | 70 | 74 |

| non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, % | 50 | 57 | 55 |

| non-narcotic analgesics, % | 16 | 15 | 20 |

| narcotic analgesics, % | 17 | 17 | 13 |

| sedatives, % | 9 | 11 | 13 |

| Cut activity, ≥7 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | 22 | 35 | 29 |

| Kept in bed ≥1 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | 20 | 22 | 26 |

| Missed work or school ≥1 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | 18 | 21 | 20 |

| Very satisfied with LBP care, % | 14 | 9 | 15 |

| Expect at least moderate improvement in LBP in 1 y, % | 36 | 33 | 31 |

| Back exercises for ≥3 d in past wk, % | 52 | 51 | 50 |

| Active exercises for ≥3 d in past wk, % | 65 | 56 | 59 |

| Massage Experience and Expectation | |||

| Prior visits to massage therapists | |||

| 0 visits, % | 26 | 32 | 31 |

| 1-9 visits, % | 43 | 38 | 44 |

| 10+ visits, % | 31 | 30 | 25 |

| Previous back or neck massage, % | 46 | 39 | 34 |

| Expected helpfulness of massage for LBP (0-10 scale), mean (SD) | 7.1 (2.0) | 7.0 (1.9) | 6.8 (2.2) |

Abbreviations: LBP, low back pain; RDQ, Roland Disability Questionnaire; SF-12, Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 12 Health Survey.

Less than 2% of data were missing for all variables except income (4%) and expected helpfulness of massage (5%-6%).

Study Treatments

Treatment adherence was 93% in the Relaxation Massage and 88% in the Structural Massage groups. Therapist recommendations for the 6 home exercise options available to both treatments were similar (Table 3). For Relaxation Massage participants, therapists recommended the relaxation CD at 41% of first visits. For Structural Massage participants, therapists recommended the psoas stretch exercise at 8% of first visits. Therapists rated participants’ mean level of adherence to self-care recommendations (mostly stretching exercises) in both groups as 7.0 on a 0 to 10 scale. After the first visit, therapists had similar expectations of the helpfulness for participants of Relaxation (mean 6.5) and Structural Massage (7.2) (scale 0 to 10).

Table 3.

Home Practices Assigned by Massage Therapists at the First and Penultimate Visits by Treatment Group

| First Visit | Penultimate Visit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Relaxation Massage (N=133) | Structural Massage (N=131) | Relaxation Massage (N=129) | Structural Massage (N=119) | |

|

| ||||

| Home Practice Assignment | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Low Back Resting Position | 31 (23) | 31 (24) | 31 (24) | 30 (25) |

| Morning Stretch in Bed | 38 (29) | 43 (33) | 58 (45) | 49 (41) |

| Cat-Cow Stretch | 23 (17) | 25 (19) | 51 (40) | 42 (35) |

| Lateral Bend | 8 (6) | 12 (9) | 36 (28) | 38 (32) |

| Walking to Help Lower Back | 22 (17) | 35 (27) | 50 (39) | 49 (41) |

| Golf Ball Roll for Plantar Fascia | 21 (16) | 18 (14) | 18 (14) | 21 (18) |

| Conscious Relaxation (Relaxation Massage only) | 55 (41) | -- | 27 (21) | -- |

| Psoas Stretch (Structural Massage only) | -- | 10 (8) | -- | 30 (25) |

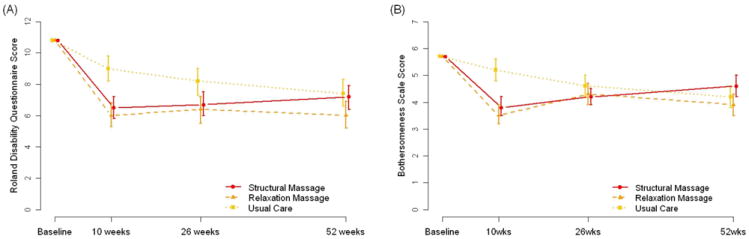

Primary Outcomes

All groups showed improved function and decreased symptoms at 10 weeks (Figure 2, Table 2). However, improvement was greater in the massage groups than in the Usual Care group. Participants in the Relaxation Massage group improved by 2.9 (95% CI: 1.8, 4.0) more points on the RDQ scale than those in the Usual Care group; those in the Structural Massage group improved by 2.5 (95% CI: 1.4, 3.5) more points (p<0.001 for both adjusted estimates). The differences in function between the two types of massage were small (adjusted difference 0.5 points (95% CI: -0.5, 1.5; P=0.35)). Similar results were found for symptom bothersomeness.

Figure 2.

Mean Roland Disability Questionnaire score (A) and symptom bothersomeness scores (B) and 95% confidence intervals by treatment group and time since randomization. Estimates are computed with GEE models with covariates set to the overall sample mean.

Table 2.

Mean Roland Disability Questionnaire and symptom bothersomeness scores and pairwise comparisons by treatment group and time since randomization

| Mean (95% CI)

|

Between-Group Differences

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes | Structural Massage | Relaxation Massage | Usual Care | Omnibus p-value‡ | Structural-Usual Care | Relaxation-Usual Care | Structural-Relaxation |

|

Adjusted analysis§

| |||||||

| Roland Disability Questionnaire | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 6.5 (5.8, 7.2) | 6 (5.3, 6.8) | 9 (8.2, 9.8) | <0.001 | -2.5 (-3.5, -1.4) | -2.9 (-4, -1.8) | 0.5 (-0.5, 1.5) |

| 26 weeks | 6.7 (6, 7.5) | 6.4 (5.5, 7.2) | 8.2 (7.3, 9) | 0.007 | -1.4 (-2.6, -0.3) | -1.8 (-3, -0.6) | 0.4 (-0.8, 1.5) |

| 52 weeks | 7.2 (6.4, 7.9) | 6 (5.2, 6.9) | 7.4 (6.6, 8.3) | 0.049 | -0.3 (-1.4, 0.9) | -1.4 (-2.6, -0.2) | 1.1 (0.02, 2.2) |

| Bothersomeness | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 3.8 (3.5, 4.2) | 3.5 (3.2, 3.9) | 5.2 (4.8, 5.6) | <.001 | -1.4 (-1.9, -0.8) | -1.7 (-2.2, -1.2) | 0.3 (-0.2, 0.8) |

| 26 weeks | 4.2 (3.9, 4.5) | 4.3 (3.9, 4.7) | 4.6 (4.2, 5) | 0.31 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 4.6 (4.2, 5) | 3.9 (3.5, 4.3) | 4.2 (3.8, 4.6) | 0.097 | -- | -- | -- |

Wald p-value.

Estimates adjusted for baseline value of outcome, age group, sex, baseline Roland Disability Questionnaire and bothersomeness score, education, body mass index, physical work demands, original cause of pain, days cut down on usual activities and medication use.

Note: Between group comparisons were only calculated if the omnibus p-value was <0.05 following the Least Significant Difference approach to control for multiple comparisons.

Effects decreased after the 10-week treatment period (Figure 2) although differences in functional improvement among the groups remained statistically significant at both 26 weeks and 52 weeks (Table 2). At 26 weeks, participants in the Usual Care group continued to function less well than those in the Relaxation Massage group (by 1.8 RDQ points, 95% CI: 0.6 to 3.0) and Structural Massage group (by 1.4 RDQ points, 95% CI: 0.3, 2.6). There were no clinically or statistically significant differences between types of massage. At 52 weeks Relaxation Massage was modestly more effective than Structural Massage (by 1.1 RDQ points, 95% CI: 0.02, 2.2). For symptoms, there were no significant differences among the 3 groups at 26 or 52 weeks.

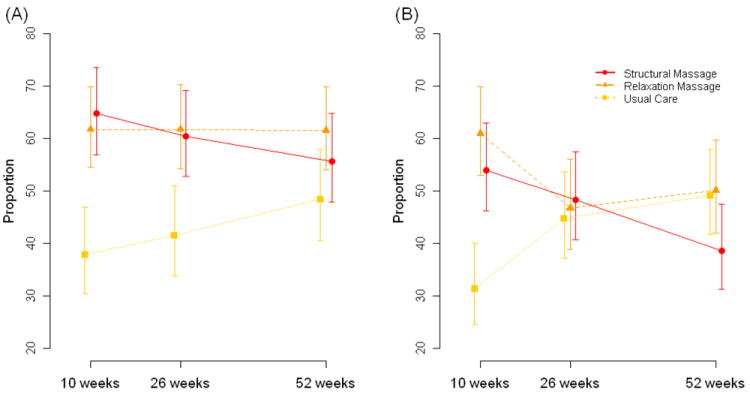

Similar results were found when primary outcomes were measured as percentage of participants improving by a clinically meaningful amount. At 10 weeks, 62%-65% of participants experienced clinically meaningful improvement in the massage groups compared with only 38% in the Usual Care group (adjusted overall P<0.001) (Figure 3). The benefits of massage diminished over time and were not statistically significant at 52-weeks. Massage recipients were more likely than those in the Usual Care group to experience clinically meaningful reductions in symptom bothersomeness at 10 weeks.

Figure 3.

Participants with improvement. Percentage of participants improving by at least 3 points on the Roland Disability Questionaire scale (A) and by at least 2 points on the symptom bothersomeness scale (B) by treatment group and time since randomization. Estimates are computed with GEE models using adjustments as described for primary and secondary outcomes with covariates set to the overall sample mean.

Secondary Outcomes

At 10 weeks, there were statistically significant differences among the groups for activity limitations (days in bed, reduced activity, days off work), patient global rating of improvement, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, satisfaction with current level of back pain, satisfaction with back pain care, and mental health (Short Form Health Survey 12) (Table 4). The two massage treatments had similar effects that were generally superior to Usual Care. Most notably, 36%-39% of participants receiving massage, versus only 4% receiving Usual Care, claimed their back pain was much better or gone. Massage did not affect narcotic analgesic use. Massage benefits persisted at 52 weeks for days of reduced activity, global improvement, and satisfaction.

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes: Adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals by treatment group and time since randomization

| Secondary outcomes | Structural | Relaxation | Usual Care | Omnibus p-value‡ | Structural Massage vs. Usual Care | Relaxation Massage vs. Usual Care | Structural vs. Relaxation Massage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Continuous Variables | Adjusted Mean (95% CI) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | |||||

| Short Form 12 Mental health scale score, mean (95% CI) | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 53.7 (52.5, 55) | 55.3 (54.2, 56.5) | 50.9 (49.5, 52.2) | <0.001 | 2.9 (1, 4.8) | 4.5 (2.7, 6.3) | -1.6 (-3.3, 0.1) |

| 52 weeks | 52.4 (50.9, 53.8) | 53.5 (52.2, 54.8) | 51.9 (50.2, 53.6) | 0.27 | -- | -- | -- |

| Short Form 12 Physical health scale score, mean (95% CI) | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 37.2 (36.4, 38) | 36.6 (35.7, 37.5) | 37.9 (37.1, 38.8) | 0.110 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 37.7 (36.8, 38.7) | 37.9 (37, 38.7) | 37.7 (36.8, 38.6) | 0.96 | -- | -- | -- |

|

| |||||||

| Binary Variables | Adjusted Percentage (95% CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Any medication use in past wk for LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 40.7% (33.9, 48.7) | 50% (42.8, 58.5) | 57.4% (50.3, 65.5) | 0.006 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1) |

| 26 weeks | 52.9% (45.9, 60.9) | 52.6% (45.2, 61.2) | 53.7% (46.6, 61.9) | 0.98 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 50.4% (43, 59.1) | 46.5% (39.2, 55.3) | 48.5% (41.3, 57) | 0.79 | -- | -- | -- |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication use in past wk for LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 28.2% (22.2, 35.9) | 30.4% (24.2, 38.2) | 40% (33.4, 48.1) | 0.027 | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) |

| 26 weeks | 34% (27.3, 42.2) | 33.2% (26.5, 41.6) | 37.1% (30.5, 45.2) | 0.69 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 34.3% (27.4, 42.9) | 25.4% (18.9, 34.3) | 29.7% (23.3, 37.9) | 0.26 | -- | -- | -- |

| Narcotic analgesic use in past wk for LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 4.6% (3, 7.3) | 5% (3, 8.5) | 5.8% (3.4, 9.9) | 0.69 | -- | -- | -- |

| 26 weeks | 5% (3.4, 7.5) | 4.6% (2.7, 8.1) | 5.2% (3.1, 8.7) | 0.93 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 4.8% (3.1, 7.3) | 4.9% (3.1, 7.9) | 4.9% (2.7, 8.7) | 0.99 | -- | -- | -- |

| Kept in bed ≥1 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 2.4% (1, 5.6) | 2.9% (1.7, 5.1) | 6.9% (4.6, 10.5) | 0.041 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.5) |

| 26 weeks | 8.1% (5.2, 12.6) | 4.3% (2.4, 7.8) | 5.7% (3.4, 9.7) | 0.153 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 7% (4.4, 11.2) | 4.7% (2.7, 8.1) | 5.5% (3.3, 9.1) | 0.50 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cut usual activities ≥7 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 2.8% (1.3, 6.1) | 3.6% (1.9, 6.7) | 9.2% (5.9, 14.5) | 0.001 | 0.3 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.8 (0.3, 2) |

| 26 weeks | 2.7% (1.3, 5.6) | 3.2% (1.7, 6.1) | 7.1% (4.3, 11.8) | 0.008 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.9 (0.3, 2.1) |

| 52 weeks | 3.1% (1.4, 6.9) | 5% (2.9, 8.8) | 8.3% (5.3, 13) | 0.041 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.9) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.6) |

| Missed work or school ≥1 d in last 4 wk due to LBP, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 2.9% (1.5, 5.8) | 5.1% (2.7, 9.5) | 8% (4.5, 14.4) | 0.018 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.7) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.2) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) |

| 26 weeks | 4.8% (2.6, 8.6) | 4.8% (2.2, 10.5) | 6.7% (3.4, 12.9) | 0.53 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 4.9% (2.5, 9.8) | 4.3% (2.4, 7.9) | 5.5% (2.9, 10.6) | 0.84 | -- | -- | -- |

| Patient global rating of improvement (much better or completely gone), % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 36.1% (28.8, 45.3) | 39.4% (31.8, 48.7) | 3.8% (1.6, 9) | <0.001 | 9.6 (3.9, 23.5) | 10.5 (4.3, 25.4) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) |

| 26 weeks | 27.4% (21, 35.7) | 29.4% (22.7, 38.2) | 10.9% (6.5, 18.1) | 0.002 | 2.5 (1.4, 4.5) | 2.7 (1.5, 4.8) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) |

| 52 weeks | 26.1% (19.8, 34.6) | 36.2% (29.1, 45) | 20.5% (14.5, 29) | 0.013 | 1.3 (0.8, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.2, 2.6) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) |

| Pleased or delighted if had current LBP for rest of life, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 15.1% (10.2, 22.5) | 20.6% (15, 28.3) | 7.1% (3.9, 12.7) | 0.007 | 2.1 (1.1, 4.3) | 2.9 (1.5, 5.7) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) |

| 26 weeks | 9.7% (6.2, 15.4) | 15.9% (10.7, 23.6) | 11.9% (7.9, 18) | 0.25 | -- | -- | -- |

| 52 weeks | 13.1% (8.6, 19.7) | 21.2% (15.4, 29.1) | 18.7% (13.1, 26.6) | 0.179 | -- | -- | -- |

| Very satisfied with back pain care, % | |||||||

| 10 weeks | 41.4% (34, 50.4) | 43.2% (35.5, 52.4) | 6.2% (3.5, 11.1) | <0.001 | 6.7 (3.6, 12.3) | 7 (3.7, 12.9) | 1 (0.7, 1.3) |

| 26 weeks | 37.6% (30.8, 45.9) | 40.7% (33.2, 49.8) | 9.4% (5.8, 15.2) | <0.001 | 4 (2.4, 6.7) | 4.3 (2.6, 7.3) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) |

| 52 weeks | 29.6% (23.2, 37.7) | 37.4% (30.2, 46.4) | 12.3% (7.7, 19.6) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.4, 4.1) | 3 (1.8, 5.1) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) |

Abbreviation: LBP=Low Back Pain

Notes: 1) Between Group Comparisons were only calculated if the omnibus p-value was <0.05 following the Least Significant Difference approach to control for multiple comparisons.. 2) Relative risk estimates were calculated using modified Poisson Regression with robust standard errors adjusted for baseline value of outcome, age group, sex, baseline Roland Disability Questionnaire and bothersomeness scores, education, body mass index, physical work demands, original cause of pain, days cut down on usual activities and medication use.

Practitioner Effects

Analysis of massage therapist effect yielded an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.007, indicating little variability among therapists compared to the overall variability of the RDQ outcome.

Co-Interventions and Subsequent Use of Massage

At 10-weeks, 33% of the Usual Care group reported visiting a provider for back pain since randomization compared with 18%-20% for the massage groups. Eight percent of Usual Care participants reported a massage visit. Between 10 and 26 weeks, 13% of Usual Care, 21% of Relaxation Massage, and 8% of Structural Massage participants reported back-related massage visits. At 52 weeks, use of massage for back pain during the previous 6-months was 18%, 26%, and 22% for these same groups. Two participants receiving Usual Care and one receiving Structural Massage had back surgery.

Cost of Back-Related Health Care After Randomization

The massage treatments received by the average participant would have cost about $540 in the community. There is no evidence that these treatments reduced costs of back pain-related health care services during the one-year post-treatment period. Median costs were $25 (Range: 0 to 8,082), $ 78 (Range: 0 to 3,764), and $38 (Range: 0 to 1,443) in the Usual Care, Relaxation Massage and Structural Massage groups, respectively.

Adverse Effects

Five of 134 participants receiving Relaxation Massage and 9 of 131 participants receiving Structural Massage reported adverse events possibly related to massage, mostly increased pain. One serious event unrelated to treatment occurred.

DISCUSSION

Although more specialized forms of massage have been found effective for chronic back pain, this may be the first large trial evaluating relaxation massage for this problem. This study found that a course of relaxation massage, using techniques commonly taught in massage schools and widely used in practice, had effects similar to those of a more specialized technique. Specifically, at weeks 10 and 26, adjusted 95% CI’s did not include mean differences in improvement between massage groups large enough to be considered clinically relevant (i.e. 2-point and 1.5-point differences for the RDQ and bothersomeness measures, respectively [8, 9]). Relaxation massage was also found more effective than usual care in improving function and decreasing pain.

Beneficial effects of both types of massage were evident immediately after the 10-week treatment period and remained statistically and clinically significant for function at the 26-week follow-up. The one-year benefits of massage were of questionable clinical significance. We found no evidence of differential effectiveness among the therapists. Both relaxation and structural massage had very low rates of adverse effects.

The most recent review evaluating the effect of massage on non-specific back pain identified 13 trials published before May 2008 [5]. As of February, 2011, two additional trials [17, 18] were identified in MEDLINE. Only the four [19-22] trials conducted in North America evaluated techniques similar to the structural massage treatment in our trial, and all found positive results. None of the previous trials evaluated relaxation massage techniques commonly taught in massage schools and widely practiced in North America.

The mechanisms explaining the beneficial effects of relaxation and structural massage remain unclear. These distinct forms of massage may trigger similar physiological effects (e.g., via local stimulation of tissue and/or through a generalized central nervous system response), or may operate through different mechanisms (e.g., structural massage may foster beneficial changes in the treated soft-tissues, while relaxation massage may operate through the central nervous system). It is also possible that improvements in pain and function are due to “non-specific effects” such as time spent in a relaxing environment, being touched, receiving care from a caring therapist, being given self-care advice, or increased body awareness [19]. A combination of these explanations is also possible.

This study has several limitations: 1) its restriction to participants with non-specific chronic low back pain in a single health care system serving a mostly White and well-off population, 2) exclusion of specific causes of back pain (e.g., disc herniations) which conceivably could benefit more from structurally focused massage, 3) possible therapist bias favoring structural massage, in which they had received specialized training--however, this seems unlikely since the results did not favor structural massage, 4) participants assigned to usual care (which often involved no additional treatment) may have been disappointed they did not get massage, possibly resulting in less positive outcome reports, 5) slight differences in exercises recommended in the two massage groups, and 6), study massage therapists may be atypical, having practiced at least 5 years and learned structural massage techniques. Uncertainties associated with these limitations make it difficult to determine the true magnitude of the benefits of massage observed in this trial. Major strengths include a large sample size, comparison of two massage techniques, inclusion of a control group, having the same therapists deliver both treatments, high treatment adherence and follow-up rates, and long-term follow-up.

Future research should explore the relative contributions of non-specific context effects and specific treatment effects on patient outcomes, whether different forms of massage produce benefits through the same or through different physiological pathways, whether less experienced therapists would produce similar results, whether fewer treatments could have achieved equivalent outcomes, and whether education and self-care recommendations contribute to the effectiveness of massage.

These results indicate that both relaxation and structural massage are reasonable treatment options for persons with chronic low back pain. Possible advantages of relaxation massage are that it is more readily accessible because it is based on techniques taught in virtually all massage schools and is slightly less expensive than more specialized forms of massage which require additional training.

Acknowledgments

The contributions of the following individuals to the successful completion of this project are gratefully acknowledged: Marissa Brooks, Alexis Williams Coatney, Erika Holden, Juanita Jackson, Christel Kratohvil, Mary Lyons, Melissa Parson, Dawn Schmidt, Diana Thompson, the 27 licensed massage therapist who provided the study treatments, the members of the Massage Therapy Research Consortium who helped develop the treatment protocols, and the managers and interviewers of the Group Health Research Institute Survey Program.

Role of the Funding Source

This trial was funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) (R01 AT 001927). It was approved by NCCAM’s Office of Clinical and Regulatory Affairs. NCCAM did not participate in the research.

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statement

Protocol: Available at www.trialsjournal.com/content/10/1/96

Statistical Code: Available to interested readers by contacting Dr. Cook at cook.aj@ghc.org

Data: Not available

Contributor Information

Daniel C. Cherkin, Email: Cherkin.d@ghc.org.

Karen J. Sherman, Email: Sherman.k@ghc.org.

Janet Kahn, Email: janet.kahn@uvm.edu.

Robert Wellman, Email: wellman.r@ghc.org.

Andrea J. Cook, Email: cook.aj@ghc.org.

Eric Johnson, Email: Johnson.ex@ghc.org.

Janet Erro, Email: erro.j@ghc.org.

Kristin Delaney, Email: Delaney.k@ghc.org.

Richard A. Deyo, Email: deyor@ohsu.edu.

References

- 1.Wolsko PM, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Kessler R, Phillips RS. Patterns and perceptions of care for treatment of back and neck pain: results of a national survey. Spine. 2003;28:292–7. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000042225.88095.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Sherman KJ, Hart LG, Street JH, Hrbek A, et al. Characteristics of visits to licensed acupuncturists, chiropractors, massage therapists, and naturopathic physicians. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:463–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eisenberg DM, David RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, Rompay MV, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Jr, Shekelle P, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:478–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T, Irvin E. Massage for low-back pain. An updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine. 2009;34:1669–1684. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ad7bd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Kahn J, Erro JH, Deyo RA, Haneuse SJ, et al. Effectiveness of focused structural massage and relaxation massage for chronic low back pain: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2009;10:96. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine. 2000;25:3100–3. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, Singer DE, Chapin A, Keller RB. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine. 1995;20:1899–1909. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:12–20. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of scale and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riess PW. Current estimates from the national health interview survey: United States, 1984. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; DHHS publication PHS 86-1584, 1986 (Vital and health statistics; series 10; no. 156) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Buuren SH, Boshuizen C, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 1999;18:681–694. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<681::aid-sim71>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li KH, Raghunathan TE, Rubin DB. Large sample significance levels from multiply imputed data using moment-based statistics and an f reference distribution. J Amer Statist Assoc. 1991;86:1065–73. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, Barlow W, Kaptchuk TJ, Street J, Deyo RA. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1081–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Krasnegor J, Theakston H. Lower back pain is reduced and range of motion increased after massage therapy. Int J Neurosci. 2001;106:131–45. doi: 10.3109/00207450109149744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preyde M. Effectiveness of massage therapy for subacute low-back pain: A randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2000;162:1815–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, et al. Lower back pain and sleep disturbance are reduced following massage therapy. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2007;11:141–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumnerddee W. Effectiveness comparison between Thai traditional massage and Chinese acupuncture for myofascial back pain in Thai military personnel: a preliminary report. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92(Suppl 1):S117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Little P, Lewith G, Webley F, Evans M, Beattie A, Middleton K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of Alexander technique lessons, exercise, and massage(ATEAM) for chronic and recurrent back pain. BMJ. 2008;337:a884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]