Abstract

Purpose

To determine the immediate changes in intraocular pressure (IOP) after laser peripheral iridotomy in primary angle-closure suspects.

Design

Prospective, randomized controlled trial (split-body design).

Participants

Seven hundred thirty-four Chinese people 50 to 70 years of age.

Methods

Primary angle-closure suspects underwent iridotomy using a neodymium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet laser in 1 randomly selected eye, with the fellow eye serving as a control. Intraocular pressure was measured using Goldmann applanation tonometry before treatment and 1 hour and 2 weeks after treatment. Total energy used and complications were recorded. Risk factors for IOP rise after laser peripheral iridotomy were investigated.

Main Outcome Measures

Intraocular pressure.

Results

The proportion of treated eyes with an IOP spike (an elevation of ≥8 mmHg more than baseline) at 1 hour and 2 weeks after treatment was 9.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.7–12.0) and 0.82% (95% CI, 0.2–1.5), respectively. Only 4 (0.54%) of 734 eyes (95% CI, 0.01–1.08) had an immediate posttreatment IOP of 30 mmHg or more and needed medical intervention. The average IOP 1 hour after treatment was 17.5±4.7 mmHg in the treated eyes, as compared with 15.2±2.6 mmHg in controls. At 2 weeks after treatment, these values were 15.6±3.4 mmHg in treated eyes and 15.1±2.7 mmHg in controls (P<0.001). No significant difference was detected in the baseline IOP of the treated and untreated eyes. Logistic regression showed that the incidence of IOP spike was associated with greater laser energy used and shallower central anterior chamber.

Conclusions

Laser peripheral iridotomy in primary angle-closure suspects resulted in significant IOP rise in 9.8% and 0.82% of cases at 1 hour and 2 weeks, respectively. Eyes in which more laser energy and a higher number of laser pulses were used and those with shallower central anterior chambers were at increased risk for IOP spikes at 1 hour after laser peripheral iridotomy.

It has been predicted that by the year 2020, 80 million people will have glaucoma, and approximately 11 million of them will be blind in both eyes. Half of this blindness will be the result of primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG).1 There are an estimated 28.2 million primary angle-closure suspects (PACS) in China alone who are considered to be at high risk of having PACG.2 Although laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) is accepted widely as one of the first-line interventions for acute and chronic PACG,3-6 as well as the treatment of choice for fellow eyes of a person having an acute angle closure attack in 1 eye,7,8 there is no direct, robust evidence demonstrating that LPI prevents acute angle closure or the development of chronic angle-closure glaucoma in asymptomatic eyes with narrow angles.

To adopt a procedure as a prophylactic treatment in a population-wide setting for asymptomatic people requires strong evidence that the benefits outweigh the harm.9 Although LPI generally is considered safe, almost no long-term data have been reported on patients treated with prophylactic LPI, and short-term complications are known to occur. Laser peripheral iridotomy can cause an acute and (usually) transient posttreatment rise in intraocular pressure (IOP) in some patients.10,11 Although previous studies indicate that the incidence of IOP spikes is reduced greatly in eyes pretreated with ocular hypotensive agents,10,12,13 the frequency and severity of IOP elevation after prophylactic LPI remains uncertain, particularly in Chinese eyes, which typically have thicker irises and thus require higher levels of energy to perforate. This study investigated the immediate impact of LPI on IOP in Chinese eyes with narrow angles, but no evidence of peripheral anterior synechia, elevated IOP, or glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Possible risk factors for IOP spikes occurring after LPI also were explored.

Patients and Methods

Patients

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University and the Ethical Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center. The trial also received institutional approval from Johns Hopkins University Hospital and Moorfields Eye Hospital (via the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine). The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Study subjects were participants in a randomized, controlled clinical trial, the Zhongshan Angle Closure Prevention trial (trial registration information available at: http://www.controlled-trials.com/ISRCTN45213099; The International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number was issued on May 6, 2008; accessed July 26, 2011). All examinations and interventions were carried out in the Clinical Research Data Collection Center at Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, a tertiary specialized hospital in Guangzhou, China. The field procedures for this trial have been reported previously elsewhere.14 In brief, in the first round of recruitment, 10,083 Guangzhou citizens aged between 50 and 70 years of age participated in the screening survey from September 2008 through August 2010. Primary angle-closure suspects were identified as having 6 or more clock hours of angle circumference in which the posterior (usually pigmented) trabecular meshwork was not visible under static gonioscopy in both eyes in which elevated IOP (defined as more than 21 mmHg, the 97.5th percentile in people with normal fields), peripheral anterior synechiae, and glaucomatous neuropathy were absent. Subjects who had an IOP rise of more than 15 mmHg from baseline in the dark room prone provocative test were excluded.

Static gonioscopy was performed using a 1 mirror Goldmann-type gonioscopy lens (Single Mirror Gonioscope; Ocular Instruments, Bellevue, WA) with low ambient illumination and a 1-mm narrow beam. Care was taken to avoid the beam falling on the pupil to prevent alteration of the angle configuration. If trabecular meshwork could not be seen because of marked iris convexity, a so-called over-the-hill view was obtained by tilting the lens toward the trabecular meshwork. Care was taken to avoid excessive tilting, which could cause inadvertent corneal indentation. A dynamic examination was performed after increasing the length and width of the beam and increasing the brightness. The participant was asked to look toward the mirror of the gonioscope, bringing the adjacent rim of the gonioscope over the central cornea. Pressure was exerted on the rim of the gonioscope to indent the central cornea. If iridotrabecular contact was not reversed satisfactorily, a dynamic examination with a 4-mirror gonioscope (Ocular Sussman 4-Mirror Gonioscope; Ocular Instruments) was carried out to determine if peripheral anterior synechia were present. Peripheral anterior synechia were defined as acquired adhesions of the iris to the corneoscleral wall crossing the scleral spur for a width of 1 clock hour or more and resulting in tenting of the peripheral iris. The angle configuration was graded in all 4 quadrants according to the Shaffer grading system and also was recorded as the circumference in which the pigmented trabecular meshwork was not visible.

Laser Peripheral Iridotomy

Written informed consent was obtained after carefully explaining the potential side effects and benefits of LPI in detail. A computer-generated list of random numbers was used to select the eye to be treated by LPI. Each subject was assigned an entry number according to his or her sequence of entering the study. The entry number corresponded to a random number in the list, that is, the first participant enrolled was assigned the first number in the list, the second patient received the second number, and so forth. The random number was kept in a sealed envelope with the corresponding sequential number written on the cover and was opened by a masked research nurse before the laser treatment.

Laser peripheral iridotomy was performed using a neodymium: yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Nd:YAG) laser (Visulas YAG III; Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA). One drop of brimonidine 0.15% (Allergan, Irvine, CA) and pilocarpine 2% (Pharmacy of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Guangzhou, China) were instilled in the intervention eye 15 minutes before treatment to reduce IOP spikes and to thin the iris so that less energy was needed to penetrate the iris. Patients were treated in the peripheral supernasal or super-temporal region (within the range from 10 to 2 o’clock) in an area where the iris appeared thinnest (preferably in a crypt). The iridotomy was performed using the Nd:YAG laser, starting at an initial setting of 1.5 mJ. All iridotomies were performed using an Abraham lens (Ocular Abraham Iridectomy YAG Laser Lens; Ocular Instruments) to focus the laser beam and to minimize possible adverse events. If bleeding occurred during the procedure, digital pressure was applied to the contact lens to achieve hemostasis. The minimum size of an iridotomy was 200 μm (0.2 mm) in diameter, judged using the 0.2-mm spot on a slit lamp. The number of laser pulses and the total energy used were recorded.

Intraocular Pressure Measurement

Intraocular pressure was measured by a research nurse, using Goldmann applanation tonometry, who was unaware of the treatment status of each eye. The research nurse was trained only in measuring IOP by Goldmann applanation tonometry and had no experience of slit-lamp examination. Goldmann applanation tonometry was repeated to establish the baseline IOP for the study before LPI. Results of 3 consecutive measurements were recorded at both the baseline and follow-up visits. The mean of the 3 measurement values was used for assessment. One hour after completion of the laser treatment, IOP was remeasured by Goldmann applanation tonometry. Individuals who had an IOP after LPI of more than 30 mmHg but less than 40 mmHg were given a second drop of brimonidine and a tablet of methazolamide 25 mg (if there was no contraindication) and were discharged with a prescription of methazolamide 25 mg 3 times daily for 2 days, at which time IOP was re-evaluated. If the IOP after LPI was more than 40 mmHg, the participant was kept in the research clinic for an additional hour after receiving the additional medications before a recheck of the IOP. If the IOP began to fall, the participant would be discharged and examined the following morning. If the IOP rose further, referral to a glaucoma specialist was made for further management. All treated subjects were discharged with dexamethasone 0.1% eye drops to be administered hourly for 24 hours then 4 times daily for 1 week after the procedure.

The current report of IOP variation after iridotomy is not the primary outcome of the trial, and therefore the sample size calculation was not taken into account for this purpose.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline ocular biometrics were compared between treated and untreated eyes using a paired t test for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. An IOP elevation of 8 mmHg or more after treatment may be clinically important, and therefore this cutoff value was used to identify patients who had an IOP spike after LPI. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with an IOP spike. Analysis was performed using Stata software version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

A total of 10 083 Chinese people between 50 and 70 years of age participated in the screening survey for the Zhongshan Angle Closure Prevention trial. Of the 938 identified as PACS, 734 people gave consent and were treated by LPI in 1 randomly selected eye, with the fellow eyes serving as controls. There were 609 females (82.9%). The mean age was 59.5±5.0 years (range, 50–70 years).

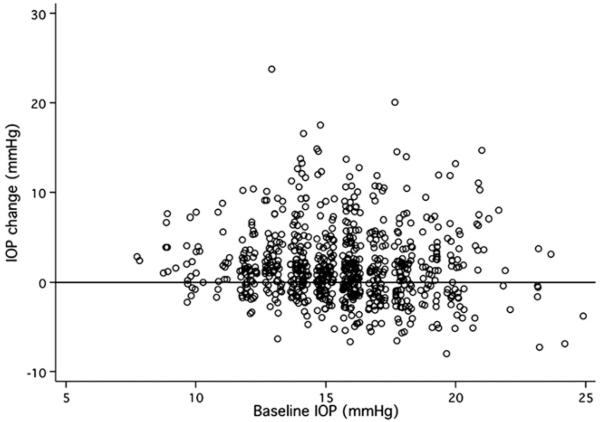

There were no significant differences between the treated and control eyes in baseline IOP, ocular biometrics, angle configuration, or IOP elevation in response to dark room prone provocative test (Table 1). At both 1 hour and 2 weeks after LPI, treated eyes had significantly higher IOP (Table 2). The proportion of IOP elevation of 8 mmHg or more and of 10 mmHg or more from baseline was 9.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.7–12.0) and 5.7% (95% CI, 4.0–7.4), respectively, at 1 hour after LPI (P<0.05, compared with control eyes at 1 hour), which dropped to 0.8% (95% CI, 0.2–1.5) and 0.3% (95% CI, –0.1 to 0.7) at 2 weeks after LPI in the treated eyes. Among the 734 subjects, only 4 (0.54%; 95% CI, 0.01–1.08) had IOP after LPI of 30 mmHg or more after 1 hour and were given 1 drop of brimonidine 0.15% (Allergan) and a tablet of methazolamide 25 mg (Fig 1). The IOP of all 4 subjects returned to normal 2 hours after medication administration. These subjects were discharged with a prescription of methazolamide 25 mg 3 times daily for 2 days, at which time the IOP was rechecked and had remained normal.

Table 1.

Ocular Biometrics of the Treated and Untreated Eyes (N = 734)

| Characteristic | Treated Eyes | Untreated Eyes |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline IOP (mmHg) | 15.6 (2.7) | 15.6 (2.7) |

| Axial length (mm)* | 22.50 (0.71) | 22.50 (0.72) |

| Lens thickness (mm)* | 4.87 (0.33) | 4.88 (0.32) |

| Central ACD (mm)* | 2.54 (0.22) | 2.55 (0.22) |

| Limbal ACD (%)† | 21.95 (7.83) | 21.95 (8.18) |

| No. of quadrants in which PTM was not visible |

3.54 (0.64) | 3.51 (0.68) |

| DRPPT (mmHg)‡ | 4.3 (2.9) | 4.2 (2.9) |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; DRPPT = dark room prone provocative test; IOP = intraocular pressure; PTM = posterior trabecular meshwork. All P>0.05.

Measured by A-scan.

Measured by van Herick grading, percentage of peripheral corneal thickness.

Intraocular pressure elevation after DRPPT test.

Table 2.

Intraocular Pressure at 1 Hour and 2 Weeks after Laser Peripheral Iridotomy

| Treated Eyes* |

Untreated Eyes |

P Value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 hr after LPI (n = 734) | |||

| IOP after LPI (mmHg) | 17.5 (4.7) | 15.2 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Change in IOP (mmHg) | 1.9 (4.1) | −0.4 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| IOP rise (≥5 mmHg), n (%) | 152 (20.7) | 13 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| IOP rise (≥8 mmHg), n (%) | 72 (9.8) | 3 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| IOP rise (≥10mmHg), n (%) | 42 (5.7) | 1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| 2 wks after LPI (n = 730) | |||

| IOP after LPI (mmHg) | 15.6 (3.4) | 15.1 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Change in IOP (mmHg) | 0.0 (3.0) | −0.5 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| IOP rise (≥5 mmHg), n (%) | 41 (5.6) | 10 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| IOP rise (≥8 mmHg), n (%) | 6 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.014 |

| IOP rise (≥10mmHg), n (%) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.157 |

IOP = intraocular pressure; LPI = laser peripheral iridotomy.

Brimonidine 0.15% and pilocarpine 2% were instilled before LPI in the treated eyes.

Figure 1.

Scatterplot showing the distribution of intraocular pressure (IOP) changes and their association with the baseline IOP.

Of the 734 treated eyes with IOP data available at 1 hour after LPI, an IOP spike (rise, ≥8 mmHg) occurred in 72 eyes. In univariate analysis, the eyes that demonstrated an IOP spike had significantly shallower anterior chamber (P = 0.012) and more quadrants of the anterior chamber angle with a Shaffer score of 1 or less (P = 0.049). The total laser energy used was significantly higher in eyes with IOP spike than those without (P<0.001; Table 3). Furthermore, eyes with an IOP spike after LPI needed significantly more shots of laser to achieve patent iridotomies (58.1±47.5 shots in eyes with IOP spike vs. 46.0±33.7 shots in eyes without). A patent iridotomy was acquired in all but 8 subjects by a single session of laser treatment. The proportion of cases requiring repeated LPI was slightly higher in eyes with IOP spike (2 of 72 eyes with IOP spike [2.8%] vs. 6 of 662 eyes without IOP spike [0.9%]), although the difference was not statistically significant. Logistic regression analysis also showed that the incidence of IOP spikes was associated with higher laser energy used and shallower central anterior chamber. Neither the number of quadrants of angle in which the posterior trabecular meshwork was not visible nor the presence of a greater circumference of angle with a Shaffer score of 2 or less were associated with IOP spikes (Table 4). Finally, the incidence of bleeding was higher in eyes with IOP spike after LPI than those without (40.3% vs. 30.7%), although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.057).

Table 3.

Angle Status, Procedure, and Complications in Treated Eyes with and without Intraocular Pressure Spike

| Characteristics | With Intraocular Pressure Spike (n = 72) |

Without Intraocular Pressure Spike (n = 662) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central anterior chamber depth (mm) | 2.49 (0.20) | 2.55 (0.22) | 0.012 |

| Average Shaffer score ≤ 2 before LPI, no. (%) |

67 (93.1) | 609 (92.0) | 0.751 |

| Quadrants in which PTM is not visible before LPI, mean (SD) |

3.49 (0.67) | 3.55 (0.64) | 0.477 |

| Change in no. of quadrants in which PTM is not visible, mean (SD) |

−2.71 (1.22) | −2.60 (1.26) | 0.498 |

| Total amount of laser energy used (mJ), mean (SD) |

205.8 (185.2) | 146.0 (118.5) | <0.001 |

| No. of laser shots applied, mean (SD) | 58.1 (47.5) | 46.0 (33.7) | 0.039 |

| No. of eyes requiring repeated laser treatment, n (%) |

2 (2.8) | 8 (0.9) | 0.349 |

| Complications, n (%) | 30 (41.7) | 203 (30.7) | 0.057 |

| Bleeding | 29 (40.3) | 203 (30.7) | |

| Corneal burn | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) |

LPI = laser peripheral iridotomy; PTM = posterior trabecular meshwork; SD = standard deviation. Intraocular pressure spike is defined as intraocular pressure elevation ≥8 mmHg 1 hour after LPI.

Table 4.

Risk Factors for Intraocular Pressure Elevation ≥8 mmHg 1 Hour after Laser Peripheral Iridotomy

| Univariate Model |

Multivariate Model* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odds Ratio

(95% Confidence Interval) |

P Value |

Odds Ratio

(95% Confidence Interval) |

P Value | |

| Age (per 10 yrs older) | 0.96 (0.59–1.56) | 0.883 | 0.94 (0.57–1.53) | 0.793 |

| Female | 0.84 (0.45–1.57) | 0.590 | 0.83 (0.44–1.56) | 0.563 |

| Baseline IOP (mmHg) | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 0.851 | 0.99 (0.91–1.09) | 0.860 |

| Total amount of laser energy used (per 100 mJ) |

1.31 (1.13–1.51) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.14–1.53) | <0.001 |

| No. of laser shots applied (per 10 shots) |

1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.008 | 1.08 (1.02–1.14) | 0.009 |

| Baseline no. of quadrants in which PTM was not visible |

||||

| 3 vs. 2 | 0.92 (0.37–2.26) | 0.854 | 0.94 (0.38–2.31) | 0.887 |

| 4 vs. 2 | 0.78 (0.33–1.82) | 0.568 | 0.80 (0.34–1.87) | 0.601 |

| Average Shaffer ≤2 before LPI | 1.16 (0.45–3.02) | 0.751 | 1.18 (0.46–3.07) | 0.728 |

| Central ACD (mm)† | 0.26 (0.08–0.81) | 0.021 | 0.25 (0.08–0.80) | 0.019 |

ACD = anterior chamber depth; IOP = intraocular pressure; LPI = laser peripheral iridotomy; PTM = posterior trabecular meshwork.

Adjusted for age, gender, and baseline IOP.

Measured by A-scan.

Discussion

This study, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, is the largest to date to investigate prospectively the immediate IOP changes after LPI and risk factors for IOP spikes induced by LPI in a cohort of PACGs recruited from the community. A previous retrospective chart review study comprised 289 eyes, of which 148 were eyes with narrow or occludable angles.10 The present study drew on data from 734 randomly selected PACS eyes, all of which were monitored in a standardized, prospective fashion.

If prophylactic treatment for asymptomatic PACGs is to be recommended, it should be proven to have benefits that outweigh risks. In this series, only 4 (0.54%) of 734 eyes experience a clinically significant IOP elevation (defined as IOP after LPI of ≥30 mmHg and requiring medical treatment). This incidence of clinically significant IOP elevation after LPI was, as expected, greatly lower than noted in previous reports in which no pretreatment was used.13,15 Shani et al15 reported a series of 212 eyes treated by Nd:YAG laser without pretreatment with any pressure-lowering medication. Despite the lower energy applied (26.9±28 mJ) in the white eyes in their study, 21.2% of all cases had an IOP elevation of more than 10 mmHg and 2.8% had an IOP increase of more than 20 mmHg. However, compared with previous studies in which eyes were pretreated with ocular hypotensive agents,16,17 the incidence of IOP rise in this series was somewhat higher. In the current study, an IOP rise of 10 mmHg or more at 1 hour and 2 weeks after LPI occurred in 42 eyes (5.7%) and 2 eyes (0.27%), respectively. Lewis et al,10 studying a mostly white population, reported a rise of more than 10 mmHg approximately 1 hour after LPI in only 2 (0.69%) of 289 eyes. In a small series of Japanese subjects treated with LPI, the incidence of a more than 10 mmHg rise over baseline was 3.4% (1 of 29 eyes). Similar to the current study, the vast majority of the series by Lewis et al (287 of 289 eyes) and all eyes in the study by Kitazawa et al17 were treated by Nd:YAG laser iridotomy. The difference in the incidence of IOP spikes between the present study and that in Lewis et al’s report may result partly from the higher energy required to create an adequate iridotomy in Chinese eyes. Although the amount of laser energy used was not identified as a risk factor for LPI-induced IOP rise in the study by Lewis et al10 the amount of energy required in their series (mean energy varied from 41.0 mJ to 49.0 mJ in different diagnostic groups) was substantially less than in the current study (mean laser energy used was 205.8±185.2 mJ in eyes with IOP spike and 146.0±118.5 mJ in eyes without), and the number of cases of IOP elevation was so small that identifying energy used as a risk factor for an IOP spike would have been impossible.

Iridotomies created using pulsed Nd:YAG lasers use plasma formation and consequent photodisruption, instead of coagulation of proteins created by continuous wave lasers such as argon, diode, and frequency-doubled YAG machines. Use of Nd:YAG lasers results in relatively more bleeding and pigment dispersion,18 and the deposition of debris from blood and pigment in the juxtacanalicular trabecular meshwork11 may impede aqueous outflow and cause IOP elevation. In the present study, bleeding occurred more often in eyes experiencing IOP spikes, although this difference was not statistically significant (40.2% vs. 30.7%; P = 0.057). Based on the photodisruption mechanism of the Nd:YAG laser, more shots of laser applied in the procedure may release more pigment particles from the iris, which could challenge the aqueous outflow facility and could induce IOP elevation. This assumption was supported by the data. In the current study, eyes with IOP spike after LPI needed significantly more shots of laser to achieve patent iridotomies than those without (58.1±47.5 shots vs. 46.0±33.7 shots).

Unlike previous studies that failed to identify an association between the amount of energy used and IOP elevation after LPI,15,19-22 this study found a clear association between higher amount of total laser energy used and the incidence of IOP spike. Although this very well may be the result of the larger sample size studied, one additional explanation is that this study exclusively treated Asian eyes with thicker and more pigmented irides. More laser energy is needed in these eyes to ensure a patent iridotomy of adequate size. It is possible that there is a threshold required before the amount of laser energy used becomes a risk factor for IOP elevation after LPI. An IOP spike after LPI may be associated with both increased aqueous production mediated by prostaglandin release and decreased outflow facility resulting from debris, denatured proteins, or cells.23,24 Higher amounts of laser energy may induce a stronger prostaglandin-mediated inflammatory response, and thus cause more active aqueous production.

The effect of Nd:YAG laser is achieved through photodisruption, rather than photocoagulation, which results in a relatively higher incidence of bleeding as compared with Argon laser iridotomy.22 Despite the higher incidence of bleeding when performing LPI using Nd:YAG lasers, these devices simplify performing the procedure, and fewer cases treated by Nd:YAG LPI are in need of retreatment in the long term than those treated by argon LPI,22,25 making Nd:YAG laser more suitable for people who have difficulty in accessing medical care. Therefore, only the single laser was used in this study, as opposed to a sequential approach or one that used only argon. Bleeding can produce extra debris and blood cells that may challenge outflow facility further and may induce elevated IOP. In the current study, the incidence of bleeding was slightly higher in eyes with IOP spike after LPI than those without, although the difference was not proved to be statistically significant (40.3% vs. 30.7%; P = 0.057).

The incidence of IOP spikes 1 hour after LPI also was associated with a shallower central anterior chamber depth. This association may be the result of a narrower angle configuration, but the present results do not support this conclusion. Measured either by Shaffer score or the number of quadrants in which the pigmented trabecular meshwork was not visible, no significant difference was found in the extent or degree of angle narrowing between eyes with or without IOP spike after LPI. Although eyes with more quadrants with a Shaffer score of 2 or less demonstrated IOP spikes, this finding was not statistically significant. Gonioscopy was not repeated 1 hour after the procedure, and therefore the degree of residual angle closure and the amount of immediate IOP elevation over the baseline at 1 hour after LPI cannot be addressed. Further analysis on the degree of IOP elevation and drainage angle width will be reconfirmed when the quantitative measurement based on anterior segment imaging data become available. Interestingly, as opposed to findings from previous studies,15,22 baseline IOP was not associated significantly with IOP spike in this study.

In the current study, the overall mean IOP in treated eyes was slightly higher at 1 hour after LPI as compared with the baseline level (17.5±4.7 mmHg vs. 15.6±2.7 mmHg) and decreased to 15.6±3.4 mmHg at 2 weeks after treatment. At both 1 hour and 2 weeks after LPI, the mean IOP in the treated eyes was only slightly higher than that in the control eyes, although the difference was statistically significant (17.5±4.7 mmHg vs. 15.1±2.6 mmHg at 1 hour after LPI [P<0.001]; 15.6±3.4 mmHg vs. 15.1±2.7 mmHg at 2 weeks after LPI [P<0.001]). Even so, this slight IOP elevation was not of clinical significance and was unlikely to incur any glaucomatous damage.

The results of this study must be seen in the context of its limitations. This study measured IOP only at 1 hour after LPI to determine the immediate change in IOP caused by the procedure and then again at 2 weeks. However, the peak of IOP elevation after LPI may not necessarily occur at 1 hour after the treatment, and it is not certain that additional IOP increases did not occur later the same day or at any point before 2 weeks after LPI. The proportion of females in the current study is higher than that of males. Although females may be overrepresented in the sample of this trial,26-28 which is commonly seen among similar studies, the current sample broadly may represent the typical gender distribution of people with or at risk of PACG. Previous population-based prevalence studies conducted in the same area as the current study by the authors29 and in south India30 have shown that the prevalence of PACS is nearly twice as high in females than in males. Prevalence studies of glaucoma in Eskimos26,27 even showed that females had angle-closure glaucoma almost 4 times as often as males.

In summary, this study investigated the immediate IOP change and risk factors for IOP spikes after laser treatment in PACGs treated by prophylactic LPI. The incidence of clinically significant IOP elevation after LPI was low. More laser energy used and shallower central anterior chamber depth were found to be risk factors for IOP elevation of 8 mmHg or more beyond baseline after LPI.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Fight for Sight, London, United Kingdom; Sun Yat-sen University Clinical Research 5010 Project, Guangzhou, China; and Fundamental Research Funds of State Key Lab, Guangzhou, China. Dr. Foster receives support from The RD Crusaders Charitable Trust (via Fight for Sight), London, United Kingdom; and the NIHR (UK) grant to the National Biomedical Research Centre (Ophthalmology), London, United Kingdom.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster PJ, Johnson GJ. Glaucoma in China: how big is the problem? Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1277–82. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.11.1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laser peripheral iridotomy for pupillary-block glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(suppl):218–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Academy of Ophthalmology Laser peripheral iridotomy for pupillary-block glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1749–58. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(13)31434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aung T, Ang LP, Chan SP, Chew PT. Acute primary angle-closure: long-term intraocular pressure outcome in Asian eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:7–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00621-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen MJ, Cheng CY, Chou CK, et al. The long-term effect of Nd:YAG laser iridotomy on intraocular pressure in Taiwanese eyes with primary angle-closure glaucoma. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008;71:300–4. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70126-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang LP, Aung T, Chew PT. Acute primary angle closure in an Asian population: long-term outcome of the fellow eye after prophylactic laser peripheral iridotomy. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:2092–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman DS, Chew PT, Gazzard G, et al. Long-term outcomes in fellow eyes after acute primary angle closure in the contralateral eye. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1087–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson JM, Jungner YG. Principles and practice of mass screening for disease [in Spanish] Bol Oficina Sanit Panam. 1968;65:281–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis R, Perkins TW, Gangnon R, et al. The rarity of clinically significant rise in intraocular pressure after laser peripheral iridotomy with apraclonidine. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:2256–9. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)91225-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krupin T, Stone RA, Cohen BH, et al. Acute intraocular pressure response to argon laser iridotomy. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:922–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33934-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu PF, Hung PT. Effect of timolol on intraocular pressure elevation following argon laser iridotomy. J Ocul Pharmacol. 1987;3:249–55. doi: 10.1089/jop.1987.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen NS, Cheung P, Hui SP. Comparing brimonidine 0.2% to apraclonidine 1.0% in the prevention of intraocular pressure elevation and their pupillary effects following laser peripheral iridotomy. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:89–92. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Y, Friedman DS, He M, et al. Design and methodology of a randomized controlled trial of laser iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure in southern China: the Zhongshan Angle Closure Prevention trial. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2010;17:321–32. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2010.508353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shani L, David R, Tessler Z, et al. Intraocular pressure after neodymium:YAG laser treatments in the anterior segment. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1994;20:455–8. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robin AL. Intraocular pressure rise after iridotomy [letter] Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1117. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050200023016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitazawa Y, Taniguchi T, Sugiyama K. Use of apraclonidine to reduce acute intraocular pressure rise following Q-switched Nd:YAG laser iridotomy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1989;20:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho T, Fan R. Sequential argon-YAG laser iridotomies in dark irides. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:329–31. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.6.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brazier DJ. Neodymium-YAG laser iridotomy. J R Soc Med. 1986;79:658–60. doi: 10.1177/014107688607901115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flohr MJ, Robin AL, Kelley JS. Early complications following Q-switched neodymium:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:360–3. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slomovic AR, Parrish RK., II Acute elevations of intraocular pressure following Nd:YAG laser posterior capsulotomy. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:973–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)33930-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robin AL, Pollack IP. A comparison of neodymium:YAG and argon laser iridotomies. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1011–6. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schrems W, Eichelbronner O, Krieglstein GK. The immediate IOP response of Nd-YAG-laser iridotomy and its prophylactic treatability. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1984;62:673–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1984.tb05794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schrems W, van Dorp HP, Wendel M, Krieglstein GK. The effect of YAG laser iridotomy on the blood aqueous barrier in the rabbit. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1984;221:179–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02134261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klapper RM. Q-switched neodymium:YAG laser iridotomy. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1017–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alsbirk PH. Anterior chamber depth and primary angle-closure glaucoma. I. An epidemiologic study in Greenland Eskimos. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1975;53:89–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1975.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arkell SM, Lightman DA, Sommer A, et al. The prevalence of glaucoma among Eskimos of northwest Alaska. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:482–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060040052031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casson RJ, Newland HS, Muecke J, et al. Prevalence of glaucoma in rural Myanmar: the Meiktila Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:710–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.107573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He M, Foster PJ, Ge J, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of glaucoma in adult Chinese: a population-based study in Liwan District, Guangzhou. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:2782–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vijaya L, George R, Arvind H, et al. Prevalence of primary angle-closure disease in an urban south Indian population and comparison with a rural population: the Chennai Glaucoma Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:655–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]