Abstract

The co-occurrence of environmental factors is common in complex human diseases and, as such, understanding the molecular responses involved is essential to determine risk and susceptibility to disease. We have investigated the key biological pathways that define susceptibility for pulmonary infection during obesity in diet-induced obese (DIO) and regular weight (RW) C57BL/6 mice exposed to inhaled lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS induced a strong inflammatory response in all mice as indicated by elevated cell counts of macrophages and neutrophils and levels of proinflammatory cytokines (MDC, MIP-1γ, IL-12, RANTES) in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Additionally, DIO mice exhibited 50% greater macrophage cell counts, but decreased levels of the cytokines, IL-6, TARC, TNF-α, and VEGF relative to RW mice. Microarray analysis of lung tissue showed over half of the LPS-induced expression in DIO mice consisted of genes unique for obese mice, suggesting that obesity reprograms how the lung responds to subsequent insult. In particular, we found that obese animals exposed to LPS have gene signatures showing increased inflammatory and oxidative stress response and decreased antioxidant capacity compared to RW. Because signaling pathways for these responses can be common to various sources of environmentally induced lung damage, we further identified biomarkers that are indicative of specific toxicant exposure by comparing gene signatures after LPS exposure to those from a parallel study with cigarette smoke. These data show obesity may increase sensitivity to further insult and that co-occurrence of environmental stressors result in complex biosignatures that are not predicted from analysis of individual exposures.

Keywords: lipopolysaccharide, LPS, obesity, lung, inflammation, genomics 1

Introduction

The systemic effects of obesity are associated with increased risks for a wide array of health problems, especially those involving inflammation, among which are insulin resistance, diabetes, fatty liver disease, airway disease, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease and increased susceptibility to infection (Hotamisligil, 2006; Amar et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007; Karlsson et al., 2010). While metabolic disorders especially affect the liver and adipose, chronic systemic inflammation from obesity also affects non-metabolic organs as evidenced by recent studies implicating diet-induced obesity in intestinal inflammation and transcriptional signaling associated with colorectal cancer (Liu et al., 2011; Pendyala et al., 2011). Other studies support a role for obesity in lung function and inflammation in response to particulate exposure, asthma, bacterial infection or influenza that, in most cases, increases susceptibility to infection or disease (Amar et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2007; Calixto et al., 2010; Gotz et al., 2011; Pekkarinen et al., 2012). In view of the strong integration between inflammatory responses and metabolic regulation, as well as the increased incidence of obesity in the U.S. population, understanding the mechanisms of these risk factors is essential for effective therapeutic strategies and early detection of pulmonary disease. In particular, understanding molecular responses of the lung, where the first encounter with inhaled agents occurs, will be critical to combating lung disease or infection, which is a leading cause of death worldwide (Jubber, 2004; Karlsson and Beck, 2010; Mancuso, 2010; Lecube et al., 2011). Chronic exposure of experimental animals to LPS induces inflammation and other pulmonary lesions commonly seen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Korsgren et al., 2012). LPS is also a well characterized constituent in cigarette smoke (Hasday et al., 1999) and urban, agricultural and house dust (Burch et al., 2010; Allen et al., 2011; Sheehan et al., 2012), all of which result in daily or repeated exposures and further support the need to understand the unique consequences of co-exposures from infectious agents (e.g. endotoxin) and obesity in the lung.

The low grade chronic inflammation present in obesity has been proposed to underlie an exacerbated inflammatory response initiated by infection, but a mechanistic understanding of the specific interactions between obesity, which is targeted to white adipose tissue, and infection in the lung is not understood. Inflammation is a hallmark feature of obese adipose tissues originating from the hypertrophy of adipocytes, which release cytokines that recruit and activate macrophages, leading in turn, to the further release of TNF-α, IL-6, acute phase reactants, C-reactive protein, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines (Hotamisligil, 2006; Karlsson and Beck, 2010). Adipocytes also release into the circulation hormone-like adipocytokines that influence glucose homeostasis, communicate lipid energy status, and possess both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties. The levels of pro-inflammatory adipocytokines are increased with obesity, while levels of anti-inflammatory adipocytokines are decreased. Moreover, increased levels of circulating free fatty acids that result from overloaded adipocytes may also contribute to establishing systemic inflammation through their binding to the Toll-like receptor 4 in other tissues.

A direct link between the low-grade chronic inflammation of obesity and pathology has been established in humans and animal models. The mechanistic link involves the endoplasmic reticulum stress activation of the transcription factor NF-κB in adipose tissue, which leads to development of insulin resistance and diabetes (Solinas and Karin, 2010). Insulin resistance has been experimentally induced in mouse skeletal muscle by endotoxin induction of NF-κB and its product, nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). Nitric oxide, which forms the highly reactive peroxynitrite by spontaneous combination with superoxide, was shown to result in tyrosine nitration of the Insulin Receptor Substrate-1 which, in turn, diminished insulin-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation and activation (Pilon et al., 2010). Similar effects of NF-κB-driven formation of peroxynitrite or other reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be relevant to the initiation of pulmonary pathologies and suggests convergent pathways of LPS exposure and obesity (Furukawa et al., 2004; Arkan et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2005; Hotamisligil, 2006; Houstis et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2008; Monteiro and Azevedo, 2010). These genes and pathways are known to be regulated in multiple lung cell types, including epithelial, endothelial, and immune alveolar macrophages (Wright et al., 2010; Viackova et al., 2011; Ali and Sultana, 2012; Guo et al., 2012). Consequently, obesity and pulmonary infectious challenges each represent complex conditions that encompass many tissue-specific molecular and cellular events that include both inflammatory and non-inflammatory processes.

Therefore, to evaluate the effect of obesity on lung inflammation, we performed a comprehensive analysis of traditional inflammatory markers and global transcriptomics of the murine lung after repeated exposures to LPS; thereby, comparing high fat diet-induced obese mice with their normal weight counterparts and integrating data from both cellular and molecular events. We find that obesity does not induce a simple exacerbation of inflammatory responses in the lung, but acts to reprogram the transcriptional response to LPS which consists of a substantial set of unique genes and pathways regulated in obese mice. A further comparison was made of the gene changes of this study with those from a parallel analysis of smoke exposure which suggests candidate biomarkers of both specific and general pulmonary exposure responses in the context of obesity.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Animal studies were performed in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Control, i.e., non-obese or regular weight (RW) and diet-induced obese (DIO) male C57BL/6 mice at 13 weeks of age were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed individually in polycarbonate solid-bottom cages on stainless-steel racks bedded with ALPHA-dri™ cellulose bedding (Shepherd Specialty Papers, Watertown, TN). Animals were acclimated to the AALAS-accredited animal facility as well as to the nose-only restraint tubes for one week prior to the initiation of exposures. The animal rooms maintained temperature and relative humidity in the target range of 22 ± 2 °C and 35 to 70% humidity, respectively, and a twelve-hour light cycle with lights starting at 0600 hr. Feed and water (delivered via automatic watering system) were provided ad libitum, except when mice were placed in exposure tubes. All animals were observed twice daily for mortality and morbidity with detailed clinical observations prior to the first exposure and the scheduled necropsy. Health screens were performed on four sentinel mice to monitor common rodent pathogens.

Experimental design

Groups of RW and DIO C57BL/6 mice (15-weeks old at start of exposures) were exposed to either filtered air (sham controls, SC) or 0.5 μg/L LPS by nose-only inhalation exposure for total of 4 days over a 10-day period as follows: 1 day on exposure, 1 day off exposure, 1 day on exposure, 3 days off exposure, 1 day on exposure, 1 day off exposure, 1 day on exposure, with necropsies occurring on the day following the last exposure (Day 11). The LPS exposure used in this study was based upon preliminary data from mice exposed to 0.5 μg/L LPS for a single 1 hr exposure to confirm that the target exposure concentration induced notable pulmonary responses, including elevated neutrophil infiltration and cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, without mortality. Similar exposures were performed with mainstream cigarette smoke (MS) by nose-only inhalation exposure for 5 hr/day over a 10-day period as previously described (Titon et al, 2012).

For this study, RW mice are defined as those mice fed a regular diet consisting of pelleted PMI® 5002 Certified Rodent Diet (PMI 5002 Rodent Diet®, Richmond, IN; ~5kcal% fat) throughout the study. DIO mice were fed a high calorie/high fat diet consisting of pelleted D12492 Rodent Diet (Research Diets Inc., New Brunswick, NJ; 60kal% fat) throughout the study starting at six weeks of age for a total of nine weeks prior to the start of the 4-day LPS exposure study. The high fat diet resulted in increased body weight of DIO mice compared with RW mice over the same time period (Table 1). The diet-induced obesity mouse was developed by Jackson Laboratory (http://jaxmice.jax.org/diomice/index.html) as a model for pre-diabetic type 2 diabetes and recent studies show that C57BL/6 mice fed a 60% high fat diet for 8 weeks have significantly increased body weights and elevated blood insulin and impaired glucose tolerance (Omar et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Body weight (in grams; mean ± SE; n=16 per group).

| RW Mice | DIO Mice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Day | sham control | LPS | sham control | LPS |

| Day 1 | 28.6 ± 0.3 | 28.6 ± 0.2 | 35.4 ± 0.6a | 35.3 ± 0.6b |

| Necropsy† | 27.9 ± 0.3 | 27.5 ± 0.2 | 35.0 ± 0.7a | 34.1 ± 0.6b |

Necropsy on day 11

p<0.05 RW-SC versus DIO-SC group

p<0.05 RW-LPS versus DIO-LPS group

A total of 16 mice/diet/exposure group were stratified by body weight prior to the initiation of exposure into two 8-mice cohorts for the purpose of collecting parallel biological samples for specific analyses. Group A was used to harvest lung tissue for gene expression studies. A separate Group B was used for BAL fluid cytology and cytokine analysis, due to the potential impact of BAL fluid collection on lung tissue analyses. On the day following the last exposure, mice from Group A were euthanized with pentobarbital and exsanguinated. The lungs from each mouse were collected with half (left lung) refrigerated in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) overnight, prior to being removed from fixative and stored at -80°C, and the remainder (right lung) flash frozen and stored at -80°C for future proteomic analyses. Mice from Group B were euthanized with an IP injection of pentobarbital followed by exsanguination via brachial arteries.

LPS and aerosol exposure system

A single lot of LPS, Serotype 055:B5 E. coli (3,000,000 EU/mg, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO: catalog # L2880) was used for all LPS exposures and for preparation of analytical LPS standards. The exposure system consisted of a Collison multi-jet nebulizer (BGI Inc., Waltham, MA) placed in a heated water bath at the front of an aerosol delivery system. Compressed air aspirated LPS solution within the nebulizer creating the aerosol. Upon dilution with high-efficiency particulate and Purafil-filtered humidified air to achieve the desired exposure concentration, LPS aerosol was directed to the inlet of a nose-only exposure carousel. LPS in the exposure carousel was measured by collecting filters at the nose port after 1 hr exposure. A minimum of 4 filter samples were collected using Whatman EPM 2000 47-mm glass fiber filter (Whatman Inc., Florham Park, NJ) from the nose ports using calibrated flow samplers to provide constant sampling flow rates of 0.5 L/min. Duplicate filters were collected from the sham control unit to ensure that no background LPS aerosol was detectable.

In addition, aerosol concentration and variability were monitored on-line by observing the output display of a condensation particle counter aerosol monitor (CPC) (Model 3022A, TSI Incorporated, St. Paul, MN) as a qualitative reference. The LPS target exposure concentration was set at 0.5 μg LPS/L air. The sampling period began approximately at the start of exposure and was terminated at the end of the 1-hr exposure period. Mean aerosol LPS exposure was calculated from the mass collected on the filter and the total volume of air drawn through the filter, which was determined by the sample time and flow rate. The LPS exposure concentration at the noseport was controlled by adjusting the LPS concentration in the stock solution. The stock solution was prepared by weighing a known mass of LPS into pyrogen-free polystyrene bottles and diluting with a known volume of endotoxin-free water (LAL Reagent Water, Associates of Cape Cod, East Falmouth, MA). LPS solution was analyzed by the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) kinetic assay, using the same LPS standards prepared for the LAL filter analysis.

The particle size distribution of LPS aerosol was measured using a Mercer-style cascade impactor (InTox Products, Moriarty, NM) with the cut-off range of 0.2-2.5 μm. The system also included monitors for exposure unit temperature, relative humidity, inlet airflow, exhaust airflow, and containment cabinet flow. All data were automatically recorded by the Battelle Exposure Data Acquisition and Control (BEDAC) System.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and cytology

BAL was performed on isolated lungs from Group B animals by cannulating the trachea and washing the lungs with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2) in a series of 6 washes. The first 2 lavage washes and the final 4 washes were pooled separately and centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation the BAL fluid supernatant from the first 2 washes was retained for ELISA protein analysis.

Cell pellets from all 6 washes for each animal were used for cytological evaluations (viability, cell count, and cell differentials). Fifty μL of this cell suspension was incubated with an equal volume of trypan blue for 3 min prior to cell counting using a hemocytometer. Viability, which was assessed using the same cell populations, was determined by absence of trypan blue stain within a cell.

Cell differentials were determined from 100 μL of lavage cell suspension mixed with 20 μL of 20% (w/v) bovine serum albumin and cytocentrifuged for 5 min at 200 rpm. The resulting precipitant was placed on a microscope slide, air dried and stained with Romanowsky-type aqueous stains. Three hundred nucleated white blood cells were counted to determine the number of alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils in LPS or sham-treated RW and DIO mice. Statistical significance was calculated by 2-factor ANOVA with a Tukey's adjusted p-value for all pairwise comparisons.

ELISA microarray analysis

Levels of specific cytokines and chemokines in BAL fluid from Group B animals were determined using a custom enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) microarray platform, as previously described (Gonzalez et al., 2008; Seurynck-Servoss et al., 2008). Briefly, individual sandwich ELISAs were developed for 18 mouse proteins (as described in Table 3), which were selected based on literature information of their involvement in lung disease and inflammation. Capture antibodies, biotinylated detection antibodies and antigens for the sandwich ELISAs were purchased as a lyophilized powder from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and antibodies had previously been demonstrated to work as pairs in sandwich ELISAs. Custom ELISA microarray chips were prepared and processed essentially as described previously (Woodbury et al., 2002; Varnum et al., 2003; Seurynck-Servoss et al., 2008). Prior to analysis, BAL fluid was diluted 1.1-fold and 11-fold using a casein-buffered saline solution such that the final solution for both dilutions contained 0.1% casein. Each dilution was analyzed in triplicate on three separate ELISA microarray chips. Since each glass slide contained 16 identical ELISA microarray chips, the three technical replicates for each sample were placed in different positions on different slides to avoid potential slide-related bias in signal intensity. Sample positioning was also blocked based on treatment group so that 4 samples from each of the 4 treatment groups were analyzed on each 16-chip slide. Standard curves were generated and sample antigen concentrations were calculated using the Protein Microarray Analysis Tool (ProMAT), a custom freeware program that we developed specifically for this purpose (White et al., 2006). BAL fluid concentrations for each protein were evaluated via a 2-factor (obesity and LPS exposure) analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with Tukey's multiple corrections test for all pairwise comparisons. This analysis was performed in MatLab® 2010a using standard functions available in the Statistics Toolbox. In addition, a strict Bonferroni multiple test correction was used to correct for the 18 ANOVA comparisons as noted (Table 3).

Table 3.

BAL fluid ELISA protein measurements (mean ± SE; n=8 per group).

| RW Mice | DIO Mice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement† (pg/mL) | sham control | LPS | sham control | LPS |

| G-CSF | 0.86 ± 0.10 | 19.6 ± 2.06a* | 0.82 ± 0.08 | 13.3 ± 2.03a,b* |

| Eotaxin (CCL11) | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 1.82 ± 0.23c | 1.26 ± 0.37 |

| IL-12 | 132 ± 24 | 1650 ± 267a* | 140 ± 30 | 961 ± 242a* |

| IL-6 | 1.54 ± 0.10 | 2.87 ± 0.17a* | 1.56 ± 0.09 | 2.06 ± 0.21a,b* |

| MDC (CCL22) | 8.8 ± 1.2 | 19.0 ± 1.9a* | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 16.3 ± 0.9a* |

| MIP-1α (CCL3) | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 7.4 ± 0.8a | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 5.7 ± 0.9a |

| MIP-1β (CCL4) | 63 ± 6 | 66 ± 4a | 45 ± 5 | 76 ± 5a |

| MIP-1γ (CCL9) | 46 ± 9 | 1174 ± 13a* | 58 ± 4 | 1020 ± 55a* |

| MIP-2 (CXCL2) | 14.5 ± 2.1 | 16.4 ± 4.5a | 10.6 ± 1.0 | 16.9 ± 1.9a |

| RANTES (CCL5) | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 13.0 ± 0.8a* | 10.6 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.5a* |

| TARC (CCL17) | 63 ± 8 | 134 ± 17a* | 60 ± 4 | 84 ± 5a,b* |

| TNF-α | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 0.4a | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 6.6 ± 0.2 |

| VEGF | 24 ± 2 | 23 ± 2 | 24 ± 2 | 16 ± 2a,b* |

p<0.05 versus respective sham control group

p<0.05 for DIO-LPS versus RW-LPS group

p<0.05 in DIO mice versus RW-SC group

passed 5% Bonferroni threshold

Additional proteins were not significant with treatment include amphiregulin, IL-1α, KC (keratinocyte chemokine), MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) and MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase-2)

Protein (abbreviations): granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF); eotaxin (CCL11); interleukins IL-6 and IL-12; macrophage-derived cytokine (MDC; CCL22); macrophage inflammatory proteins (MIP) MIP-lα (CCL3), MIP-1β (CCL4), MIP-1γ (CCL9) and MIP-2 (CXCL2); small inducible cytokine A5 (RANTES; CCL5); thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC; CCL17); tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α); and vascular endothelial growth factor AA (VEGF).

Gene expression and pathway analysis

Whole genome microarray analysis was performed in lung tissues from Group A animals using Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430A 2.0 chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA; 22,690 probesets). Total RNA was collected using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA integrity and purity was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 3 μg of total RNA in the presence of an oligo-dT primer containing a T7 RNA polymerase promoter, and an in vitro transcription reaction was performed in the presence of a mixture of biotin-labeled ribonucleotides to produce biotinylated cRNA from the cDNA template, according to manufacturer's protocols (Affymetrix One-Cycle Target Labeling Kit). Biotin-labeled cRNA (15 μg) was fragmented to a size range between 50-200 bases for array hybridization. After hybridization, the arrays were washed, stained with streptavidin-phycoerythrin, and scanned at a resolution of 2.5 microns using an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000. Quality control parameters were assessed throughout the experimental process to measure the efficiency of transcription, integrity of hybridization, and consistency of qualitative calls. The synthesis of the cDNA and cRNA, and the fragmentation of cRNA were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Spike-in control transcripts also were monitored to verify hybridization integrity.

Raw intensity data were quantile normalized by Robust Multi-Array Analysis (RMA) summarization (Bolstad et al., 2003), transformed to its diet-specific sham control (Bolstad et al., 2003) and subjected to ANOVA (Kerr et al., 2000) with Tukey's multiple corrections test and 5% false discovery rate calculation (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) using GeneSpring v.11 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA). For data transformation, the background is defined as the diet phenotype (DIO or RW) for each treatment group. Z-scores were used to compare expression patterns between DIO and RW mice exposed to LPS. Unsupervised bidirectional hierarchical clustering of microarray data was performed using Euclidean distance metric and centroid linkage clustering to group treatments and gene expression patterns by similarity. The clustering algorithms, heat map visualizations and centroid calculations were performed with Multi-Experiment Viewer (Saeed et al., 2003) software based on log2 expression ratio values or z-score values. Principal components analysis was performed on treatment groups with GeneSpring v.11 (Silicon Genetics) using non-transformed normalized intensity values. Functional enrichment statistics and network analysis were determined with Metacore (GeneGo, St. Joseph, MI) to identify the most significant biological processes affected by LPS and DIO. The statistical scores in MetaCore are calculated using a hypergeometric distribution where the p-value represents the probability of a particular mapping arising by chance for experimental data compared to the background, which were all genes on the Affymetrix platform. Integration of data between LPS and smoke transcriptional studies was performed in Bioinformatics Resource Manager v2.3 using the merge data tools (Shah et al., 2007).

Quantitative RT-PCR analyses

Real time quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to verify gene expression changes measured by Affymetrix microarray analysis. Complementary DNA was synthesized from total RNA via reverse transcription with oligo-dT priming (ImProm-II Kit, Promega, Madison, WI). Pairs of oligodeoxynucleotide PCR primers were designed to amplify cDNA encoding the target genes using the Universal Probe Library Assay Design Center (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Whenever possible, primer pairs spanned introns to eliminate amplification of contaminating genomic DNA. PCR reactions were carried out using FastStart DNA MasterPLUS SYBR Green I reagents (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions in a Roche Lightcycler II (Roche Applied Science). Cycle parameters were: denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 55°C for 5 s, and elongation at 72°C for 10 s for 45 cycles. Melting curve analyses were performed from 60°C to 95 °C in 0.5°C increments. All qRT-PCR data were normalized to the level of cyclophilin A (product of the mouse Ppia gene) transcript levels and are reported as mean (± standard error) relative to controls from duplicate analyses. Statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA with Tukey's multiple corrections test and were considered significant if p<0.05.

Results

Obesity was induced and maintained in C57BL/6 mice with a high calorie/high fat diet regime, which resulted in average weight gains of 24% for the DIO mice relative to the mice fed a regular chow (RW) (Table 1). Both RW and DIO mice were exposed to 0.5 μg/L LPS by nasal inhalation for 1 hr/day 4 times during 10 days of the study. Neither group of mice experienced significant weight loss over the period of exposure ruling out the possibility of stress to the animals by the repeated handling and LPS exposures. BAL and lung tissue samples for analysis were collected 24 h after the final LPS exposure in order to capture persistent changes rather than acute responses from the last exposure.

Obesity modulates, but does not induce pulmonary inflammation

Pulmonary inflammation was evaluated by the levels of both cellular and molecular inflammatory markers using cytology and ELISA protein microarray in BAL fluid from RW and DIO mice after LPS or sham exposure. We find that LPS exposure elicits a distinct pulmonary inflammatory response in both RW and DIO mice as shown by marked increases in the number of inflammatory cells, i.e., neutrophils, pulmonary alveolar macrophages, and lymphocytes (Table 2). In contrast, eosinophils, which mediate allergic hyperreactivity, show no significant (p<0.05) change in cell number, consistent with the role of LPS as an inflammatory stimulus rather than an allergen. The lack of significant changes in cell counts comparing RW with DIO untreated mice indicates the absence of an underlying cellular inflammation in obesity under the current study design. However, obesity intensifies some aspects of the LPS inflammatory response of mice, as evidenced by a significantly (p<0.05) greater elevation observed in macrophage numbers in DIO mice relative to those of RW mice. Neither LPS-induced increases in neutrophils nor lymphocytes are further increased in DIO as compared with RW mice.

Table 2.

BAL fluid cytology measurements (mean ± SE; n=8 per group B).

| RW Mice | DIO Mice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement (#/μL) | sham control | LPS | sham control | LPS |

| PAMc | 412.2 ± 39.2 | 820.9 ± 73.3a | 392.0 ± 32.7 | 1279.4 ± 141.2a,b |

| PMNd | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 858.3 ± 138.5a | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 951.1 ± 66.5a |

| LYMPHe | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 25.3 ± 6.1a | 0.9 ± 0.5 | 32.0 ± 5.9a |

| EOSINf | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

p<0.05 versus respective sham control group

p<0.05 RW-LPS versus DIO-LPS group

PAM, pulmonary alveolar macrophages

PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils)

LYMPH, lymphocytes

EOSIN, eosinophils

To evaluate inflammatory signaling in the lung, we measured the levels of 18 mouse proteins, largely cytokines and chemokines, which are known to be involved in lung disease and inflammation using a custom sandwich ELISA protein microarray platform. We find that LPS exposure results in significant (p<0.05) elevation of multiple inflammatory cytokines in BAL fluid from both RW and DIO mice; these include: G-CSF (granulocyte-colony stimulating factor), the interleukins, IL-6 and IL-12, MDC (macrophage-derived chemokine), RANTES (regulated upon activation normal T-cell expressed), TARC (thymus and activation-regulated chemokine) and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP) members, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-1γ, and MIP-2 (Table 3). All of these proteins have been previously demonstrated to be part of an endotoxin-induced inflammatory response in the lung (Meng et al., 2006). However, 5 of 18 proteins assayed (amphiregulin, IL-1α, KC (keratinocyte chemokine), MCP-1 (monocyte chemotactic protein-1) and MMP-2 (matrix metalloproteinase-2)) exhibited no apparent response to LPS exposure or obesity and TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor-alpha) displayed only modest elevations, consistent with the early and transient expression (within 4-6 h) of these proteins (Moffatt et al., 2002; Lotter et al., 2006; De Filippo et al., 2008; Wijagkanalan et al., 2008; van Zoelen et al., 2011).

No intrinsic effect of obesity was observed when comparing sham controls of RW with DIO mice, with the exception of eotaxin which, although not elevated by LPS exposure, was moderately increased (p<0.05) in untreated DIO mice in agreement with a prior study reporting elevated levels of eotaxin in both serum and adipose tissue of C57B/6 mice fed a high fat diet (Vasudevan et al., 2006). In view of eotaxin's role both as a potent chemoattractant of eosinophils and in induction of eosinophil-mediated bronchial inflammation, its obesity-related increases in the lung, although not sufficient to activate eosinophils in the current study, may contribute to the greater severity of asthma in obese human subjects (Mancuso, 2010).

Whereas the obese state exhibits no additional molecular markers of inflammation, the LPS response in DIO mice is altered in comparison to that of RW mice (Table 3). For example, elevations in G-CSF, IL-6 and TARC levels occur to a lesser extent in obese mice as compared with RW mice (p<0.05), suggesting an impaired innate immune response or a delay in expression. Similarly, levels of VEGF, which were not altered by LPS in RW mice, showed significant (p<0.05) reduction after LPS exposure in DIO mice. Taken together, these results suggest that obesity alone does not initiate pulmonary inflammation as measured by standard cellular and secreted protein inflammatory markers, but rather provides an altered biochemical setting in the lung in which an inflammatory stimulus produces an altered response.

Obese animals show a unique gene response to endotoxin

To obtain a more comprehensive view of the altered environment and early pulmonary events that form the basis for different endotoxin responses in obese animals, we measured the transcriptional responses in lung tissue of RW and DIO mice after LPS or sham exposure. These data represent a tissue level response in lung reflective of all cell types (lung and infiltrating immune cells) present in the tissue at the time of sampling. Gene expression profiles were assessed with Affymetrix 430A 2.0 microarrays, which provide full coverage of the mouse genome. Complete results in the form of supplemental raw data files are available online through GEO ID: GSE38092. Gene expression values for all subsequent analyses are presented as fold-change (Log2) for each treatment (RW-LPS or DIO-LPS) compared to its diet-specific sham control (RW-SC or DIO-SC) unless otherwise stated.

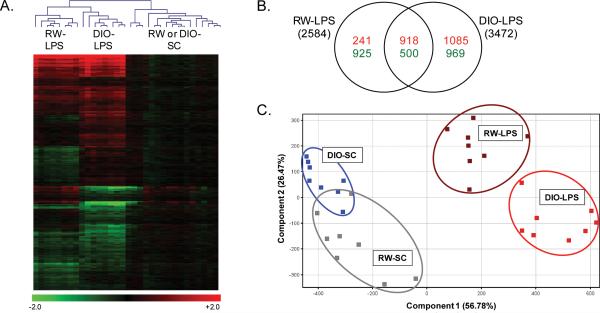

We find that a total of 4,893 genes were significantly (p<0.01) regulated by LPS in this study, including 2,584 unique genes differentially expressed in RW-LPS mice as compared with RW-SC mice and 3,472 differentially expressed genes in DIO-LPS mice as compared with DIO-SC mice. Changes in gene expression ranged from >80-fold up-regulated to >10-fold down-regulated. Bidirectional hierarchical clustering of the entire significant dataset correctly classified all sample replicates (n=8) by treatment group (Figure 1A). The clustering heatmap illustrates both the strong response by LPS in mouse lung compared with sham control and the distinct differences in gene signatures between RW and DIO mice after LPS exposure. As illustrated by the Venn diagram (Figure 1B), each group exhibits a unique set of differentially expressed genes in addition to a significant overlap of shared gene changes. Moreover, the number of genes down-regulated by LPS is similar between RW and DIO mice, but almost twice as many significant genes were up-regulated by LPS in obese mice compared with regular weight mice (2,003 versus 1,159 genes, respectively).

Figure 1. Transcriptional Response of RW and DIO mice to LPS.

Bidirectional hierarchical clustering by Euclidean distance and principal component analysis (PCA) of gene expression in lung tissues (N=8) from regular weight (RW) and diet-induced obese (DIO) mice exposed to LPS or sham control (SC). (A) 4,893 genes were significantly regulated (p<0.01, 5% FDR) across the study in RW mice exposed to LPS (RW-LPS) or DIO mice exposed to LPS (DIO-LPS) compared with the diet-specific sham control. (B) Venn diagram of genes up- (red) or down- regulated (green) by LPS in RW and DIO mice. (C) PCA clustering of 4,893 significant genes on condition using non-transformed normalized intensity values. For panel A, values are log2 fold change for all treatments compared with the diet-specific sham control; red, green, and black represent up-regulated, down-regulated and unchanged genes, respectively. For panel C, values are z-score transformations across the DIO-LPS and RW-LPS groups; each point represents data for a single animal.

The differences between each treatment group by LPS exposure and diet phenotype can be visualized by principal components analysis of the 4,893 differentially expressed gene set (Figure 1C). As illustrated by the scatterplot where each point represents an individual animal, each treatment group was clearly defined and the majority of the variance was accounted for by two components, i.e., principal component 1 (56.7% variance), describing the effect of LPS exposure compared with sham control treatments, and principal component 2 (26.5% variance), describing the separation between DIO and RW phenotypes. Most notable is the wide separation of the LPS-exposed groups from the untreated groups. Further, the slight overlap in RW and DIO control groups contrasts with the wider separation of RW and DIO groups after LPS exposure. Taken together, this overview of the gene expression profiles highlights the significant transcriptional response of mouse lung to a mild short-term, repeated exposure to LPS. The clear shift in LPS response in obese mice reflects the differential expression of an extensive and unique set of genes in addition to a common inflammatory response shared with non-obese mice.

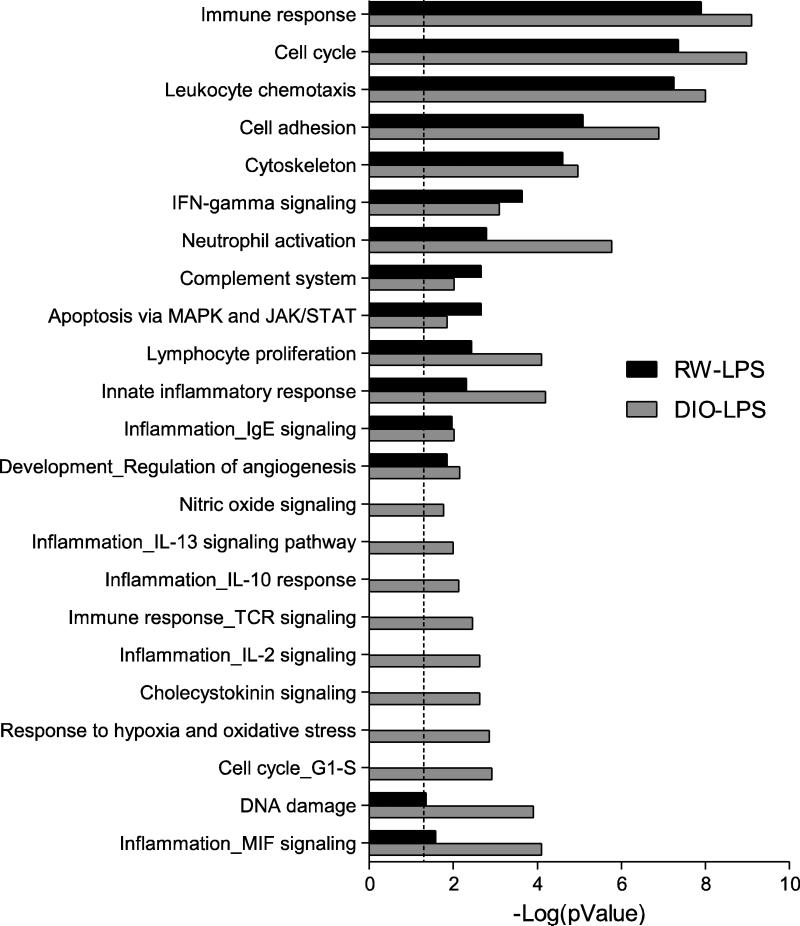

We further investigated the biological processes that were associated with the LPS transcriptional responses in RW and DIO mice, performing statistical enrichment of biological process networks for the differentially expressed genes using GeneGo MetaCore analysis software. The results show significant (p<0.05) enrichment of 24 processes that fall into two categories (Figure 2). One group consists of processes that are common to both DIO and RW mice after LPS exposure and thus independent of diet phenotype; most of these processes show greater enrichments in obese animals. The second group of enriched processes was comprised of genes unique to obese mice exposed to LPS, which include several additional inflammatory signaling networks, as well as processes for response to hypoxia and oxidative stress, cholecystokinin signaling, and iNOS signaling. In particular, the significant over representation of genes associated with iNOS signaling in the DIO-LPS group (provided as Supplementary Figure S1), involves up-regulation of several primary mediators of this process, i.e., Jak2, Mapk14 (p38 MAP kinase), Tnfa and Nfkb. The Nfkb transcription factor provides a central node of interaction in this network and suggests generation of nitric oxide and formation of peroxynitrite in LPS-exposed obese animals. However, it has also been proposed that iNOS-generated nitric oxide in the lung primarily plays a role in resolving LPS-induced airway inflammation by inhibition of NF-κB via S-nitrosylation of its p65 subunit and the concomitant arrest of the multiple pro-inflammatory gene products of this transcription factor (Marshall et al., 2009; Kelleher et al., 2011). The fate of nitric oxide in the balance between peroxynitrite and S-nitrosylation will depend on the redox state of the tissues.

Figure 2. Comparison of LPS-induced gene processes in lung from RW and DIO mice.

Functional enrichment of gene processes by LPS exposure in lung of regular weight (RW) and diet-induced obese (DIO) mice using MetaCore network processes (GeneGo). The RW-LPS group (black bars) represent enrichment of functions for the 2,584 genes differentially regulated (p<0.01) in LPS-exposed RW mice compared with RW-SC. The DIO-LPS group (gray bars) represent enrichment of functions for the 3,472 genes differentially regulated (p<0.01) in LPS-exposed DIO mice compared with DIO-SC mice. The dashed line indicates the threshold for significance (p<0.05). Each category contains a minimum of 15 genes.

The presence of the cholecystokinin signaling in DIO-LPS mice may represent additional participation of an antioxidant response as cholecystokinin is a negative regulator of LPS-induced ROS generation in pulmonary interstitial macrophages (Meng et al., 2002). Several anti-inflammatory processes are uniquely represented in the LPS exposed obese mouse lung; for example, IL-10 and IL-13 signaling pathways act to suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine production in T-cells, monocytes and macrophages (Lentsch et al., 1999; Opal and DePalo, 2000; Frommhold et al., 2011). Taken together, these gene changes suggest a more extensive inflammatory and immune response to endotoxin in obese mice, which includes both pro-inflammatory pathways as well as those regulatory gene products that enable inflammatory resolution as well as prevent the overproduction of ROS.

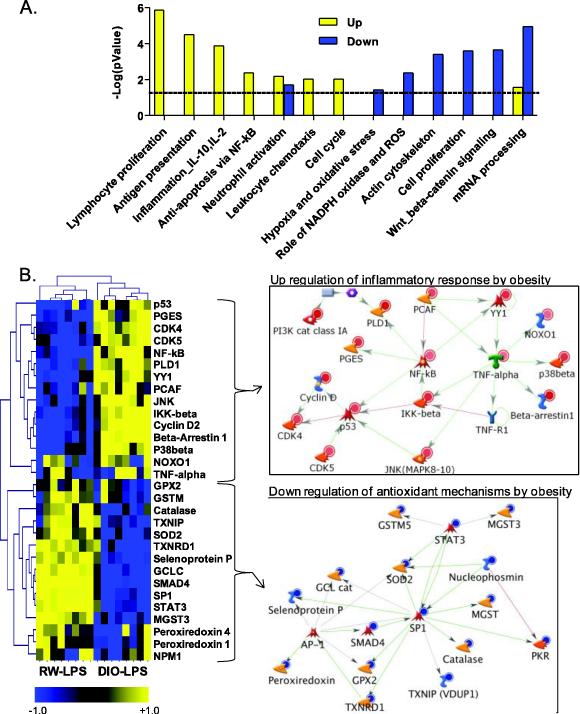

As a means to identify how the biological processes unique to the LPS response of obese mice were regulated, we restricted the MetaCore query to the 3,475 genes significantly different (p<0.01) in LPS-exposed DIO mice as compared with RW-LPS mice, thus excluding the 1,418 genes that represent the common LPS response shared with RW mice. We further separated this transcriptional signature into sub-lists based on direction of transcriptional regulation (up or down) for pathway-based enrichment. Overall, functional enrichment of the unique obesity response to LPS resulted in distinct biological processes for up- and down-regulated genes, including 2,142 and 1,333 genes, respectively, in obese mice after LPS exposure (Figure 3A). As expected, the biological processes in Figure 3A overlap with those listed for DIO-LPS animals in Figure 2, but provide additional information about the mechanism of the pulmonary endotoxin response in obese animals. Biological processes that were significantly (p<0.05) up-regulated include those important for inflammation and immune response whereas down-regulated processes (e.g., hypoxia and oxidative stress, NADPH oxidase and ROS, actin cytoskeleton, cell proliferation, Wnt/beta catenin signaling, and mRNA processing), suggest a greater susceptibility to high levels of ROS and impaired repair capabilities (Figure 3A). In particular, LPS induces a network of genes in the obese phenotype for inflammation that is associated with an inflammatory stress response mediated by Nfkb and Tnfa, which act as central nodes in the network with p53 acting as a secondary node (Figure 3B). Down-regulated genes in the combined network for oxidative stress and ROS include peroxiredoxin, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, superoxide dismutase and thioredoxin reductase, which are specifically involved in antioxidant mechanisms and detoxification of ROS (Figure 3B). While antioxidant genes were repressed by obesity, other genes associated with NAD(P)H oxidase were strongly up-regulated by LPS treatment, including Noxo1 (NAD(P)H oxidase organizer 1), which is a major source of reactive oxygen species (Yao et al., 2007). These data predict that obesity results in elevated inflammatory stress in the lung after LPS exposure, which is exacerbated by an impaired antioxidant capacity potentially leading to overproduction of ROS intermediates (superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, and NO-derived reactive species). Production of ROS intermediates may further lead to oxidative modification of cellular proteins. Thus, the systemic effects of obesity on the lung include the regulation of numerous genes that modify the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory processes as well as associated pro- and anti-oxidants.

Figure 3.

Obesity Gene Signature from functional enrichment and network analysis of significant targets in the obesity gene signature, which includes 3,475 differentially regulated (p<0.01) genes in lung of diet-induced obese (DIO) LPS-exposed mice compared with regular weight (RW) LPS-exposed mice. (A) Statistical enrichment of biological network processes (GenGo, MetaCore). Yellow bars represent functions for up-regulated genes and blue bars represent functions for down-regulated genes by obesity after LPS exposure. Dashed line indicates threshold for significance (p<0.05). Each category contains a minimum of 15 genes. (B) Heatmap and associated networks for genes within the inflammation and oxidative stress/ROS categories. Values in heatmap are z-score transformations across the DIO-LPS and RW-LPS groups. Yellow, blue, and black represents positive, negative and unchanged genes, respectively, for DIO-LPS compared to RW-LPS. Insets show the networks for genes up- or down-regulated by obesity. Red and blue circles indicate gene products that are increased or decreased, respectively. Legend for network objects is included in Supplementary Figure S1-B.

Potential Biomarkers of Exposure and Early Detection of Disease

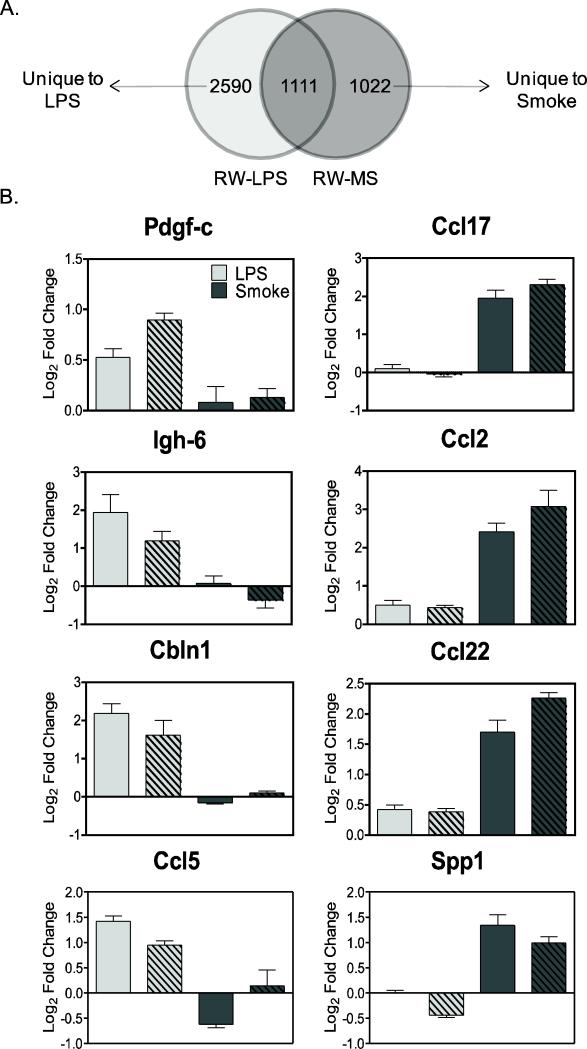

The ability to detect changes in functional gene networks in response to pulmonary toxicant exposure within the context of obesity offers the possibility to monitor individual responses to specific toxicants towards the goal of early detection of disease. To identify candidate biomarkers of response that are unique to exposure by a specific pulmonary toxicant, yet independent of a generalized inflammatory response, we compared gene expression profiles from RW and DIO mice after exposure to LPS (from this study) with those from a similar study of mice exposed to mainstream cigarette smoke (MS). The cigarette smoke study involved exposure of C57BL/6 mice to MS (250 ug/L WTPM) for 5 hr/day for 8 days over a 10-day period and resulted in significant (p<0.05) regulation of 2,133 genes in lung of RW-MS mice compared to sham control (GEO ID: GSE38093). Comparison of the smoke dataset to the 3,701 significant (p<0.05) differentially expressed genes in RW-LPS mice vs. RW-SC, resulted in two lists of genes unique to each type of pulmonary exposure (Figure 4A). Individual biomarkers from each gene list were identified to differentiate between cigarette smoke and LPS exposures based on the criteria that they were significant for only one treatment and were independent of the obese phenotype. For example, platelet derived growth factor C (Pdgfc), immunoglobulin heavy chain 6 (Igh6), cerebellin 1 precursor (Cbln1) and chemokine ligand 5 (Ccl5/Rantes) are significantly up-regulated by LPS independent of both obesity and smoke exposure, while smoke uniquely up-regulates chemokine ligand 17 (Ccl17/Tarc), chemokine ligand 2 (Ccl2/Mcp1), chemokine ligand 22 (Ccl22/Mdc) and osteopontin (Spp1; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Comparison of LPS and mainstream cigarette smoke (MS) gene signatures in lung of regular weight (RW) mice (N=8) by (A) cDNA microarray analysis resulted in 2,590 and 1,022 genes (p<0.05, 5% FDR) unique to LPS and MS treatments, respectively. (B) Individual transcriptional biomarkers that show exposure-specific response after treatment with LPS (Pdgf-c, Igh-6, Cbln1, Ccl5) and MS (Ccl17, Spp1, Ccl2, Ccl22) independent of DIO or RW phenotype were identified from the individual gene signatures. Values are expressed as fold change (log2; mean ± SE) compared to diet-specific sham controls (SC). Light gray bars represent LPS exposure; dark grey bars represent MS exposure; solid bars represent RW animals; hatched bars represent DIO animals.

Several of these markers have been confirmed at the protein level by protein ELISA measurements in mouse BAL fluid after LPS or smoke exposure. For example, the inflammatory cytokine RANTES was induced by LPS in both DIO and RW groups (but not smoke), while MCP-1 was induced by MS but not LPS (Table 3 and companion smoke paper). While TARC and MDC were significantly (p<0.05) up-regulated by both LPS and MS treatment, protein levels were much higher after MS exposure than LPS, approximately 5- to10-fold or 15-to-30-fold for TARC and MDC, respectively, consistent with the transcriptional data (Table 3; Figure 4B and companion smoke paper).

Significant (p<0.05) biological processes that are unique to LPS or MS exposure were identified in MetaCore (GeneGo) and filtered to only those processes that are independent for obese phenotype (Table 4). The data suggest that several processes relevant for cytoskeleton, cell adhesion, cholecystokinin signaling and the B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) pathway in immune response are unique to LPS exposure (but not smoke) while those important for inflammatory protein C signaling and protein folding are important to smoke exposure but not LPS.

Table 4.

Exposure-specific biological processes that are independent of general inflammation associated with obesity

| Biological Processa | RW pValueb | DIO pValuec |

|---|---|---|

| Unique to LPS: |

||

| Anti-Apoptosis via MAPK and JAK/STAT | 0.031 | 0.002 |

| Cell adhesion_Amyloid proteins | 0.021 | 0.042 |

| Cell adhesion_Cadherins | 0.010 | 0.011 |

| Cell adhesion_Cell junctions | 0.029 | 0.000 |

| Cell cycle_Mitosis | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Cytoskeleton_Cytopl asmic microtubules | 0.023 | 0.000 |

| Cytoskeleton_Spindle microtubules | 0.000 | 0.014 |

| DNA damage_Checkpoint | 0.030 | 0.000 |

| Immune response_BCR pathway | 0.018 | 0.000 |

| Proteolysis_Ubiquitin-proteasomal proteolysis | 0.026 | 0.022 |

| Signal Transduction_Cholecystokinin signaling | 0.032 | 0.000 |

| Signal transduction_ESR1-nuclear pathway | 0.021 | 0.002 |

| Transcription_Chromatin modification | 0.042 | 0.024 |

| Translation_Translation initiation | 0.001 | 0.000 |

| Unique to Mainstream Cigarette Smoke (MS): |

||

| Inflammation_Protein C signaling | 0.045 | 0.019 |

| Proliferation_Negative regulation of cell proliferation | 0.018 | 0.005 |

| Protein folding_Response to unfolded proteins | 0.002 | 0.000 |

Biological processes identified as significantly (p<0.05) enriched in lung tissue after LPS or smoke exposure (independent of obesity) using Metacore (GeneGo) software

Pvalue for biological processes enriched from significant genes in regular weight (RW) animals

Pvalue for biological processes enriched from significant genes in diet-induced obese (DIO) animals

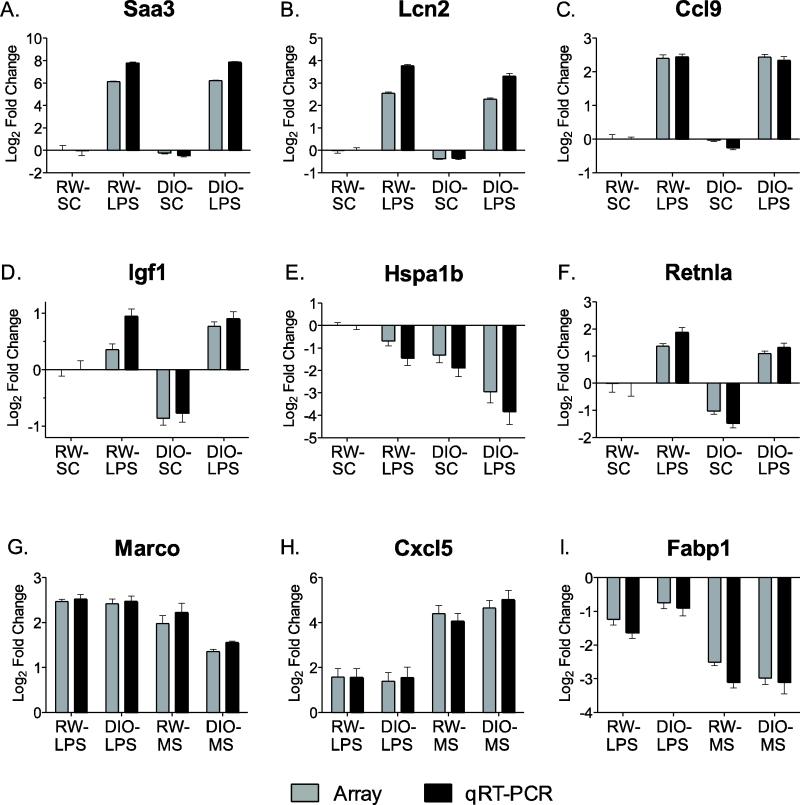

Quantitative RT-PCR confirmation

To confirm the microarray results, we conducted qRT-PCR measurements on a subset of genes that were selected based on their differential expression in response to exposure or diet phenotype (Figure 5 with full list and statistics available in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). This confirmation included genes that were differentially regulated by LPS exposure compared to DIO-SC or RW-SC and by the DIO phenotype compared to RW groups. We further confirmed genes that were differentially regulated between LPS and MS exposures. Overall, the qRT-PCR analysis confirmed the cDNA array data, both qualitatively and quantitatively, for individual genes and further validated the gene signatures that were identified based on differential response across treatment groups. For example, genes that were part of the LPS signature, including Saa3, Lcn2 and Ccl9 (Mip1g) were significantly (p<0.01) up-regulated in RW-LPS mice (Figure 5A-C). MIP-1γ protein was also induced by LPS in BAL fluid as measured by ELISA microarray (Table 3). Genes in the obesity signature were altered by the DIO phenotype and were significantly (p<0.01) different between DIO-LPS and RW-LPS or sham control mice, such as Igf1, Hspa1b and Retnla (Figure 5D-F). Genes that were significant for the LPS or MS exposure in mouse lung included Marco, Cxcl5 and Fabp1 (Figure 5G-I). Marco was up-regulated by both LPS and smoke, while Cxcl5 and Fabp1 were unique to smoke exposure.

Figure 5.

Comparison of gene expression in lung measured by cDNA microarray (gray bars) and real time qRT-PCR (black bars). Values are expressed as fold change (Log2; mean ± SD) compared to regular weight sham controls (RW-SC). Panels A-C, genes induced by LPS. Panels D-F, genes altered by diet-induced obesity (DIO). Panels G-I, comparison of genes regulated by LPS and mainstream cigarette smoke (MS) exposure independent of diet.

Discussion

The complex interactions between environmental factors and genetics are increasingly recognized for their role in disease etiology and progression. Obesity represents an often-ignored phenotypic dimension for gene-environment interaction studies that could potentially confound our interpretation of response unless it is addressed. In this study, we determined the impact of obesity in otherwise healthy mice on pulmonary inflammation after short-term, repeated exposures to inhaled endotoxin over a period of two weeks. This exposure model is relevant to that experienced in the human population from episodic exposures to low levels of LPS present in respirable dust and indoor air due to cigarette smoking (Nevalainen et al., 2002; Sebastian et al., 2006; Tuder et al., 2006), but not for chronic, long-term exposures. Similarly, the high fat diet-induced animal model of obesity used in this study is reflective of the typical mode of obesity present in humans although the short-term duration precludes assessment of the more profound, chronic effects of diet-induced obesity such as type 2 diabetes. Moreover, use of diet-induced obesity avoids the comorbidities and metabolic abnormalities of genetic animal models such as the leptin deficient, ob/ob or leptin receptor deficient, db/db mice (Mandel and Mahmoud, 1978; Chandra, 1980; Mancuso et al., 2002; Ikejima et al., 2005). Even after only 9 weeks of a high fat diet, these mice not only exhibited overt obesity with significant weight gains (Table 1), but also exhibited systemic effects of obesity on a peripheral organ, i.e., the lung. While obesity, in itself, produced no overt pulmonary inflammation as measured by classic cellular and cytokine markers in this study (Tables 2 and 3), obesity-related changes in the cellular and tissue environment were clearly articulated upon challenge with the bacterial endotoxin, LPS. The obesity-related increase observed in macrophage numbers suggests the potential for a greater susceptibility to chronic inflammation as is typical of COPD (Barnes, 2004; Lee et al., 2007; Korsgren et al., 2012). The obesity-related reductions in cytokines G-CSF, IL-6, TARC were in agreement with a similar blunted cytokine response previously measured in serum of obese mice after infection with P.gingivalis (Barnes, 2004; Amar et al., 2007). Other studies have also reported a delay in the immune response of obese models such that pro-inflammatory cytokines in BAL fluid are repressed early after influenza or allergen challenge followed by an elevation at later time points (Smith et al., 2007; Calixto et al., 2010). Collectively, these data show that obesity impairs the ability to mount an appropriate immune response, which could have consequences for a broad range of environmental exposures or diseases.

In addition to the altered cytokine and cellular inflammatory responses, gene expression profiling showed striking differences in transcriptional responses to endotoxin, where the majority of gene changes in LPS-exposed DIO mice were unique to obese animals and not observed in the response of normal weight mice (Figures 1 and 2). Pathway analysis indicated that endotoxin exposure in DIO mice induced regulation of networks of genes that are predicted to change the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory mechanisms and pro- and antioxidant processes (Figures 2, 3, and S1). Of particular relevance are the genes unique to the obesity response associated with iNOS-mediated inflammation and NAD(P)H oxidase signaling, including repression of antioxidant enzyme responses (Figure 3). As NAD(P)H oxidase plays a primary role in the abundant formation of superoxide during lung inflammation, simultaneous generation of nitric oxide would be predicted to result in peroxynitrite formation, with the resulting cellular and tissue damage, as reported in e.g., LPS-induced acute lung injury (Sharma et al., 2010). In this study, unique LPS processes, as compared with smoke-exposed lungs (Table 4), highlights the damaging aspects of LPS exposure, as for example, DNA damage, multiple proteolysis and proteasomal pathways, mitosis, transcription, and translation processes. One of the multiple targets of peroxynitrite is the superoxide dismutase isoform, SOD2, for which nitration of the active site, Tyr-34 inhibits its ability to detoxify superoxide, thus leading to additional formation of peroxynitrite (Pacher et al., 2007). On the other hand, nitric oxide has the potential to inhibit NAD(P)H oxidase through S-nitrosylation and further resolve pulmonary inflammation by S-nitrosylation and concomitant inhibition of NF- κB (Kelleher et al., 2011). Thus the functional consequences of many of the gene responses altering pro- and antioxidants in the lung may depend upon the balance of S-NO and peroxynitrite with respect to the fate of induced nitric oxide.

Inhalation of LPS results in both pulmonary and systemic inflammation through activation of innate immunity as an essential part of host defense (Martin and Frevert, 2005). Our report that repeated short-term exposures to LPS results in strong elevation of pulmonary macrophages, neutrophils and pro-inflammatory cytokines is in good agreement with previous reports (Lee et al., 2007). Furthermore, the LPS transcriptional response we observed is similar to that of earlier studies showing up-regulation of inflammatory and acute phase response genes, including serum amyloid A 3 (Saa3), macrophage receptor with collagenous structure (Marco), lymphocyte antigen 6 complex (Ly6i), and down regulation of heat shock response (Hspa1b) (Meng et al., 2006).

LPS is a component of the gram-negative bacteria cell wall that is capable of inducing superoxide as a defense mechanism produced by NADPH oxidase (Nox family) in macrophages andneutrophils. All LPS-treated animals in this study exhibited a strong induction of Noxo1 (NADPH oxidase organizer 1), which activates NADPH oxidase (NOX1), a major source of reactive oxygen species that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of COPD (Banfi et al., 2003; Rahman, 2005; Meng et al., 2006). Due to the similarities in the pathogenesis of COPD and pulmonary infection, we suggest that data from these studies can also be interpreted for understanding the inflammatory, morphological and functional deficits associated with infection-related COPD observed in humans.

Because signaling pathways for oxidative stress and inflammation can be common to various sources of environmentally induced lung damage, we have identified biomarkers that are indicative of specific toxicant exposure and are not common to chronic systemic inflammation associated with obesity. Previous studies have demonstrated that LPS produces a pattern of inflammatory and immune response that is distinguishable from exposure to cigarette smoke (Meng et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007). Results from the present study, which show that these transcriptional patterns are largely influenced by obesity for both LPS and cigarette smoke exposure, have directed our comparison of pathway and gene markers that are unique to toxicant only and not additionally modified by the obese phenotype. Biomarkers, such as Ccl17, Ccl2, Ccl22, Spp1, protein C signaling and response to unfolded proteins pathway, are unique for smoke exposure in lung and did not overlap with either LPS exposure or obesity. Alternatively, other biomarker genes and pathways, such as Pdgfc, Igh6, Cbnl1, Ccl5, cell adhesion and cytoskeleton pathways, are unique for LPS treatment. Some of these biomarkers are supported at the protein level from ELISA measurements and may help to define key biological pathways that define susceptibility to environmental stress from LPS and cigarette smoke without the confounding biosignature of obesity. These individual and biological process-level biomarkers will also be used to direct analysis of plasma and lung proteomics in the identification of unique biomarkers of exposure to pulmonary toxicants, which is an ongoing project in our laboratory. Other studies have observed consistent gene expression signatures and conservation of biomarkers between lung and less-invasive samples obtained from nasal and buccal epithelium after smoke exposure (Sridhar et al., 2008).

Our study demonstrates that pre-existing conditions that result in systemic inflammation may alter the immune response to respiratory infection and, potentially, to other respiratory diseases or exposures. These studies, which evaluate short-term exposure to complex environmental stressors, demonstrate the need for additional chronic exposures and dose-response studies to further determine whether the changes observed were adaptive short-term responses or sustained processes which could lead to altered disease susceptibility. Additionally, the co-occurrence of lung toxicants and/or disease may result in outcomes that are not predicted from the additive effects of individual stressors. The fact that co-occurrence of environmental factors is common in complex human disease also makes it difficult to decipher the individual roles of each causative factor. Multiple contributing environmental factors can also result in exacerbation of lung diseases, such as COPD, that result in decreased lung function (e.g. with age) or hospitalization in acute situations (Fabbri et al., 2008; Perera et al., 2012). Patients with a history of frequent exacerbations were found to have elevated bronchial airway inflammatory markers (Bhowmik et al., 2000) suggesting that multiple environmental factors resulting in pulmonary inflammation, including obesity, smoking or infection, contribute to COPD exacerbations.

Conclusion

We report for the first time global transcriptional profiling of lung tissue in an experimental model of diet-induced obesity challenged by endotoxin exposure, demonstrating early systemic involvement of the lung in the obese state, which is articulated through endotoxin challenge. The substantial transcriptional changes in obese mice detail an altered balance between anti- and pro-inflammatory and oxidant processes that result in increased susceptibility to lung infection and inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Obesity modulates inflammatory markers in BAL fluid after LPS exposure.

Obese animals have a unique transcriptional signature in lung after LPS exposure.

Obesity elevates inflammatory stress and reduces antioxidant capacity in the lung.

Toxicant-specific biomarkers predict exposure independent of systemic inflammation.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by cooperative agreement U54/ES016015 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Pacific Northwest National Laboratory is a multiprogram national laboratory operated by Battelle for the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract DEAC05-76RL01830.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations: ANOVA-analysis of variance; BAL-bronchoalveolar lavage; DIO-diet-induced obesity; ELISA-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LAL-limulus amebocyte lysate; LPS-lipopolysaccharide; MS-mainstream cigarette smoke; qRT-PCR-quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; ROS-reactive oxygen species; RW-regular weight; SC-sham control

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ali F, Sultana S. Repeated short-term stress synergizes the ROS signalling through up regulation of NFkB and iNOS expression induced due to combined exposure of trichloroethylene and UVB rays. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;360:133–145. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J, Bartlett K, Graham M, Jackson P. Ambient concentrations of airborne endotoxin in two cities in the interior of British Columbia, Canada. J Environ Monit. 2011;13:631–640. doi: 10.1039/c0em00235f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amar S, Zhou Q, Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb Y, Leeman S. Diet-induced obesity in mice causes changes in immune responses and bone loss manifested by bacterial challenge. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20466–20471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710335105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkan MC, Hevener AL, Greten FR, Maeda S, Li ZW, Long JM, Wynshaw-Boris A, Poli G, Olefsky J, Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfi B, Clark RA, Steger K, Krause KH. Two novel proteins activate superoxide generation by the NADPH oxidase NOX1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3510–3513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ. Mediators of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2004;56:515–548. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate- a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmik A, Seemungal TA, Sapsford RJ, Wedzicha JA. Relation of sputum inflammatory markers to symptoms and lung function changes in COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2000;55:114–120. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch JB, Svendsen E, Siegel PD, Wagner SE, von Essen S, Keefe T, Mehaffy J, Martinez AS, Bradford M, Baker L, Cranmer B, Saito R, Tessari J, Linda P, Andersen C, Christensen O, Koehncke N, Reynolds SJ. Endotoxin exposure and inflammation markers among agricultural workers in Colorado and Nebraska. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2010;73:5–22. doi: 10.1080/15287390903248604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto MC, Lintomen L, Schenka A, Saad MJ, Zanesco A, Antunes E. Obesity enhances eosinophilic inflammation in a murine model of allergic asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:617–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra RK. Cell-mediated immunity in genetically obese C57BL/6J ob/ob) mice. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:13–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo K, Henderson RB, Laschinger M, Hogg N. Neutrophil chemokines KC and macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 are newly synthesized by tissue macrophages using distinct TLR signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2008;180:4308–4315. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri LM, Luppi F, Beghe B, Rabe KF. Complex chronic comorbidities of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:204–212. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frommhold D, Tschada J, Braach N, Buschmann K, Doerner A, Pflaum J, Stahl MS, Wang H, Koch L, Sperandio M, Bierhaus A, Isermann B, Poeschl J. Protein C concentrate controls leukocyte recruitment during inflammation and improves survival during endotoxemia after efficient in vivo activation. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2637–2650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa S, Fujita T, Shimabukuro M, Iwaki M, Yamada Y, Nakajima Y, Nakayama O, Makishima M, Matsuda M, Shimomura I. Increased oxidative stress in obesity and its impact on metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1752–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI21625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RM, Seurynck-Servoss SL, Crowley SA, Brown M, Omenn GS, Hayes DF, Zangar RC. Development and validation of sandwich ELISA microarrays with minimal assay interference. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:2406–2414. doi: 10.1021/pr700822t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotz AA, Rozman J, Rodel HG, Fuchs H, Gailus-Durner V, Hrabe de Angelis M, Klingenspor M, Stoeger T. Comparison of particle-exposure triggered pulmonary and systemic inflammation in mice fed with three different diets. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2011;8:30. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-8-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Ma N, Horibe Y, Kawanishi S, Murata M, Hiraku Y. Nitrative DNA damage induced by multi-walled carbon nanotube via endocytosis in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;260:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasday JD, Bascom R, Costa JJ, Fitzgerald T, Dubin W. Bacterial endotoxin is an active component of cigarette smoke. Chest. 1999;115:829–835. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature05485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houstis N, Rosen ED, Lander ES. Reactive oxygen species have a causal role in multiple forms of insulin resistance. Nature. 2006;440:944–948. doi: 10.1038/nature04634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikejima S, Sasaki S, Sashinami H, Mori F, Ogawa Y, Nakamura T, Abe Y, Wakabayashi K, Suda T, Nakane A. Impairment of host resistance to Listeria monocytogenes infection in liver of db/db and ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 2005;54:182–189. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jubber AS. Respiratory complications of obesity. Int J Clin Pract. 2004;58:573–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1368-5031.2004.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson EA, Beck MA. The burden of obesity on infectious disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:1412–1424. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson EA, Sheridan PA, Beck MA. Diet-induced obesity in mice reduces the maintenance of influenza-specific CD8+ memory T cells. J Nutr. 2010;140:1691–1697. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher ZT, Potts EN, Brahmajothi MV, Foster MW, Auten RL, Foster WM, Marshall HE. NOS2 regulation of LPS-induced airway inflammation via S-nitrosylation of NF-{kappa}B p65. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L327–333. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00463.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr MK, Martin M, Churchill GA. Analysis of variance for gene expression microarray data. J Comput Biol. 2000;7:819–837. doi: 10.1089/10665270050514954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsgren M, Linden M, Entwistle N, Cook J, Wollmer P, Andersson M, Larsson B, Greiff L. Inhalation of LPS induces inflammatory airway responses mimicking characteristics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32:71–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecube A, Sampol G, Munoz X, Ferrer R, Hernandez C, Simo R. TNF-alpha system and lung function impairment in obesity. Cytokine. 2011;54:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KM, Renne RA, Harbo SJ, Clark ML, Johnson RE, Gideon KM. 3-week inhalation exposure to cigarette smoke and/or lipopolysaccharide in AKR/J mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19:23–35. doi: 10.1080/08958370600985784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentsch AB, Czermak BJ, Jordan JA, Ward PA. Regulation of acute lung inflammatory injury by endogenous IL-13. J Immunol. 1999;162:1071–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Brooks RS, Ciappio ED, Kim SJ, Crott JW, Bennett G, Greenberg AS, Mason JB. Diet-induced obesity elevates colonic TNF-alpha in mice and is accompanied by an activation of Wnt signaling: a mechanism for obesity-associated colorectal cancer. J Nutr Biochem. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotter K, Hocherl K, Bucher M, Kees F. In vivo efficacy of telithromycin on cytokine and nitric oxide formation in lipopolysaccharide-induced acute systemic inflammation in mice. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:615–621. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso P. Obesity and lung inflammation. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:722–728. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00781.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso P, Gottschalk A, Phare SM, Peters-Golden M, Lukacs NW, Huffnagle GB. Leptin-deficient mice exhibit impaired host defense in Gram-negative pneumonia. J Immunol. 2002;168:4018–4024. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel MA, Mahmoud AA. Impairment of cell-mediated immunity in mutation diabetic mice (db/db). J Immunol. 1978;120:1375–1377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall HE, Potts EN, Kelleher ZT, Stamler JS, Foster WM, Auten RL. Protection from lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury by augmentation of airway S-nitrosothiols. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:11–18. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1186OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- Martin TR, Frevert CW. Innate immunity in the lungs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:403–411. doi: 10.1513/pats.200508-090JS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng AH, Ling YL, Zhang XP, Zhang JL. Anti-inflammatory effect of cholecystokinin and its signal transduction mechanism in endotoxic shock rat. World J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:712–717. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v8.i4.712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng QR, Gideon KM, Harbo SJ, Renne RA, Lee MK, Brys AM, Jones R. Gene expression profiling in lung tissues from mice exposed to cigarette smoke, lipopolysaccharide, or smoke plus lipopolysaccharide by inhalation. Inhal Toxicol. 2006;18:555–568. doi: 10.1080/08958370600686226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffatt JD, Jeffrey KL, Cocks TM. Protease-activated receptor-2 activating peptide SLIGRL inhibits bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into the airways of mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;26:680–684. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.26.6.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro R, Azevedo I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/289645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevalainen M, Raulo SM, Brazil TJ, Pirie RS, Sorsa T, McGorum BC, Maisi P. Inhalation of organic dusts and lipopolysaccharide increases gelatinolytic matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in the lungs of heaves horses. Equine Vet J. 2002;34:150–155. doi: 10.2746/042516402776767277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar B, Pacini G, Ahren B. Differential development of glucose intolerance and pancreatic islet adaptation in multiple diet induced obesity models. Nutrients. 2012;4:1367–1381. doi: 10.3390/nu4101367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opal SM, DePalo VA. Anti-inflammatory cytokines. Chest. 2000;117:1162–1172. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:315–424. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekkarinen E, Vanninen E, Lansimies E, Kokkarinen J, Timonen KL. Relation between body composition, abdominal obesity, and lung function. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2012;32:83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2011.01064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendyala S, Neff LM, Suarez-Farinas M, Holt PR. Diet-induced weight loss reduces colorectal inflammation: implications for colorectal carcinogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:234–242. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.002683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera PN, Armstrong EP, Sherrill DL, Skrepnek GH. Acute exacerbations of COPD in the United States: inpatient burden and predictors of costs and mortality. COPD. 2012;9:131–141. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2011.650239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon G, Charbonneau A, White PJ, Dallaire P, Perreault M, Kapur S, Marette A. Endotoxin mediated-iNOS induction causes insulin resistance via ONOO induced tyrosine nitration of IRS-1 in skeletal muscle. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15912. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I. Oxidative stress in pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2005;43:167–188. doi: 10.1385/CBB:43:1:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N, Braisted J, Klapa M, Currier T, Thiagarajan M, Sturn A, Snuffin M, Rezantsev A, Popov D, Ryltsov A, Kostukovich E, Borisovsky I, Liu Z, Vinsavich A, Trush V, Quackenbush J. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian A, Pehrson C, Larsson L. Elevated concentrations of endotoxin in indoor air due to cigarette smoking. J Environ Monit. 2006;8:519–522. doi: 10.1039/b600706f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seurynck-Servoss SL, Baird CL, Miller KD, Pefaur NB, Gonzalez RM, Apiyo DO, Engelmann HE, Srivastava S, Kagan J, Rodland KD, Zangar RC. Immobilization strategies for single-chain antibody microarrays. Proteomics. 2008;8:2199–2210. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AR, Singhal M, Klicker KR, Stephan EG, Wiley HS, Waters KM. Enabling high-throughput data management for systems biology: the Bioinformatics Resource Manager. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:906–909. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kumar S, Wiseman DA, Kallarackal S, Ponnala S, Elgaish M, Tian J, Fineman JR, Black SM. Perinatal changes in superoxide generation in the ovine lung: Alterations associated with increased pulmonary blood flow. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;53:38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan WJ, Hoffman EB, Fu C, Baxi SN, Bailey A, King EM, Chapman MD, Lane JP, Gaffin JM, Permaul P, Gold DR, Phipatanakul W. Endotoxin exposure in inner-city schools and homes of children with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AG, Sheridan PA, Harp JB, Beck MA. Diet-induced obese mice have increased mortality and altered immune responses when infected with influenza virus. J Nutr. 2007;137:1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas G, Karin M. JNK1 and IKKbeta: molecular links between obesity and metabolic dysfunction. FASEB J. 2010;24:2596–2611. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-151340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar S, Schembri F, Zeskind J, Shah V, Gustafson AM, Steiling K, Liu G, Dumas YM, Zhang X, Brody JS, Lenburg ME, Spira A. Smoking-induced gene expression changes in the bronchial airway are reflected in nasal and buccal epithelium. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titon SC, Karin NJ, Webb-Robertson BJM, Waters KM, Mikheev V, Lee KM, Corley RA, Pounds JG, Bigelow DJ. Impaired transcriptional response in the murine heart to cigarette smoke in the setting of high fat diet and obesity. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 2012 doi: 10.1021/tx400078b. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Arap W, Pasqualini R, Petrache I. State of the art. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:503–510. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-054MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zoelen MA, Verstege MI, Draing C, de Beer R, van't Veer C, Florquin S, Bresser P, van der Zee JS, te Velde AA, von Aulock S, van der Poll T. Endogenous MCP-1 promotes lung inflammation induced by LPS and LTA. Mol Immunol. 2011;48:1468–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum SM, Covington CC, Woodbury RL, Petritis K, Kangas LJ, Abdullah MS, Pounds JG, Smith RD, Zangar RC. Proteomic characterization of nipple aspirate fluid: identification of potential biomarkers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;80:87–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1024479106887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan AR, Wu H, Xydakis AM, Jones PH, Smith EO, Sweeney JF, Corry DB, Ballantyne CM. Eotaxin and obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:256–261. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viackova D, Pekarova M, Crhak T, Bucsaiova M, Matiasovic J, Lojek A, Kubala L. Redox-sensitive regulation of macrophage-inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in vitro does not correlate with the failure of apocynin to prevent lung inflammation induced by endotoxin. Immunobiology. 2011;216:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM, Daly DS, Varnum SM, Anderson KK, Bollinger N, Zangar RC. ProMAT: protein microarray analysis tool. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1278–1279. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]