Abstract

To fully understand the modes of action of multi-protein complexes, it is essential to determine their overall global architecture and the specific relationships between domains and subunits. The transcription factor AbrB is a functional homotetramer consisting of two domains per monomer. Obtaining the high-resolution structure of tetrameric AbrB has been extremely challenging due to the independent character of these domains. To facilitate the structure determination process, we solved the NMR structures of both domains independently and utilized gas-phase cleavable chemical crosslinking and LC/MSn analysis to correctly position the domains within the full tetrameric AbrB protein structure.

Keywords: NMR, solution structure, chemical crosslinking, domain orientation, AbrB, gas-phase cleavable

Introduction

To fully understand the modes of action of multi-protein complexes, it is essential to determine their overall global architecture and the specific relationships between domains and subunits. Certainly, X-ray crystallographic studies can provide such information, but only when suitable crystals are available. In many cases, independently moving domains may make crystallization difficult [1]. Using NMR to provide such information is not always practical. Often, protein domains are separated by long distances, making NOE driven NMR investigations problematic. Both classical NOE experiments and isotope-filtered/edited NOE experiments are limited to rather short distance restraints (5–6Å) [2]. Techniques such as paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) and Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) have been developed to provide long-range distance information. However, these methods often require difficult and deleterious modifications to be made to the protein to obtain the distance restraints [3, 4]. An appealing alternative approach comes in the form of chemical crosslinking coupled with mass spectrometry. Chemical crosslinking can be performed under physiological conditions with modest amounts of crosslinking reagents that do not alter protein structure [5, 6], which makes it a viable approach to complement high-resolution structures and offers insight into spatial orientation [7–9].

Chemical crosslinking covalently attaches the side chains of specific residues (in most cases lysines) throughout the protein and defines maximal inter-residue distances that can be used as constraints in modeling. A particularly useful crosslinking agent is the collision-induced dissociative crosslinker disuccinimidyl-succinamyl-aspartyl-proline (SuDP), which incorporates a gas-phase labile aspartyl-protyl amide bond in the linker region [7]. SuDP crosslinks lysine residues with a maximum inter-residue distance of 23.9Å, the maximal distance of Cα to Cα between the two crosslinked lysines. During LC/MSn analysis, the D-P bond of the crosslinked peptide (M1-SuDP-M2) is preferentially cleaved in MS2 and allows the identification of each released peptide (M1-SuD and P-M2) by MS3 sequencing [7–9]. In this study, we show the value of SuDP chemical crosslinking to correctly orient the independent N- and C-terminal domains of the transition state regulator protein AbrB. In this case, NMR NOE distance restraints were unable to provide any useful information, and the extra constraints provided by the crosslinking enabled the complete structure of the protein to be solved.

AbrB is a transcription factor that has homologues in a variety of organisms [10]. Its primary role is to regulate processes needed for both growth and survival during times of bacterial decision making. AbrB consists of 94 residues and is a functional homotetramer, consisting of two domains per monomer [11, 12]. The DNA-binding N-terminal domain (AbrBN) has a looped-hinge helix fold and forms a homodimer with another AbrBN monomer [13–15, 18]. The C-terminal domain (AbrBC) forms a homodimer with another AbrBC monomer, but is not involved directly in binding DNA. Obtaining the high-resolution structure of tetrameric AbrB has been extremely challenging due to the independent character of these domains. To facilitate the structure determination process, we solved the NMR structures of both AbrBN and AbrBC independently (pdb code 1Z0R and unpublished data, respectively)[18]. However, because of their disconnected nature, we have been unable to orient each domain with respect to one another using NOE approaches. As described below, SuDP chemical crosslinking and subsequent LC/MSn analysis were used to correctly position the domains within the full tetrameric AbrB protein structure.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The SuDP reagent was synthesized as previously described [7–9, 17]. Sequencing-grade modified trypsin was purchased from Promega (www.promega.com). Acetonitrile (HPLC grade) and formic acid (ACS reagent grade) were from Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com). Water was distilled and purified using a High-Q 103S water purification system (www.high-q.com). All other reagents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich-Fluka (www.sigmaaldrich.com) unless otherwise stated.

Protein Expression and Purification

Full length Bacillus subtilis AbrB (residues 1–94) was expressed and purified as described previously [16]. Briefly, full length AbrB (residues 1–94) from B. subtilis was cloned into expression vector pET-28a (Novagen) with a Thrombin cleavable N-terminal histidine tag and transformed into BL21(DE3) cells (Genesee) for expression in LB media at 37°C. At OD600 of ~0.7 the temperature was reduced to 30°C and expression induced with 1mM IPTG. The cells were harvested by centrifugation 4 hours postinduction at 7,000g for 15 min. Cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM imidazole, 0.02% sodium azide at pH 7.9) and sonicated with resulting cell lysate clarified by centrifugation at 15,000g and the resulting supernatant was passed over Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen). The N-terminal histidine tag was removed from the purified protein by incubation with Thrombin and loaded onto a Q-Sepharose ion exchange column (GE Healthcare). Samples for crosslinking were dialyzed into working buffer (10 mM KH2PO415 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3) at pH 7.5 and concentrated to 0.5 mg/mL.

Crosslinking and proteolytic digestion of AbrB

AbrB was crosslinked and digested as previously described [7]. Briefly, protein samples were prepared in PBS buffer and crosslinked with SuDP using a final protein-to-crosslinker ratio of 1:100. The crosslinked proteins were digested with trypsin (protein-to-trypsin ratio of 1:50, w/w) overnight at 37°C.

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis

Crosslinked peptide samples were separated using an Easy-nLC system (www.thermoscientific.com) coupled online to an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (www.thermoscientific.com). Reversed-phase separation of the peptides from the protein digest was accomplished using a 75 µm i.d. × 25 cm column packed in-house with 3 µm 200 Å Magic C18AQ stationary phase (Michrom Bioresources Inc., www.michrom.com) coupled to a Acclaim PepMap 100 µm i.d. × 2 cm trap column (www.thermoscientific.com). The mobile phases consisted of (A) 0.1% formic acid in 2% acetonitrile and (B) 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. A total of 100nmol of peptide digest was loaded onto the reversed-phase trap column for each injection and then separated using a linear gradient of 1% B/min from 5% B to 40% B at a flow rate of 300 nl/min.

Two-step LC/MSn strategy and data analysis

LC/MSn data-dependent acquisition and data analysis were performed as previously described [9]. Briefly, an LC/MS2 experiment was acquired in the orbitrap under low-energy collision induced dissociation (CID) to favor the preferential cleavage of our gas-phase cleavable crosslinker SuDP. Subsequently, an LC/MS3 analysis targeting each of the released peptides from the inter-peptide crosslinks was performed based on the inclusion list generated from the LC/MS2 data via our in-house developed algorithm CXLinkS. The LC/MS3 data were analyzed as described previously [9] with the database containing the AbrB sequence.

Results and Discussion

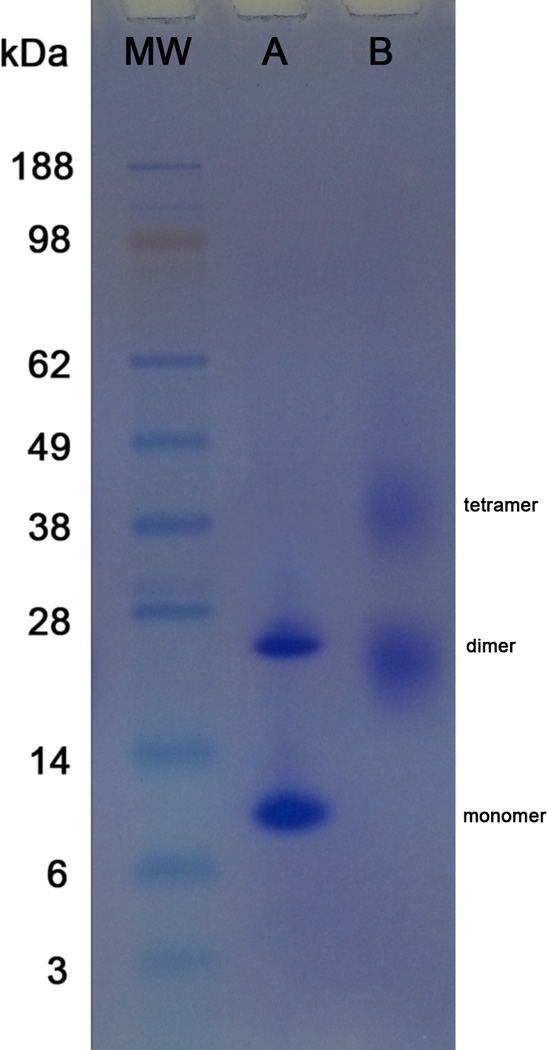

Successful AbrB crosslinking with 1:100 molar ratio of SuDP reagent were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and shown in Figure 1. Crosslinking (Lane B) resulted in two crosslinked bands compared to un-crosslinked AbrB (Lane A). While un-crosslinked AbrB has two bands consisting of monomer and dimer states (10.1 and 22 kDa, respectively), crosslinked AbrB is comprised of two bands at dimer and tetramer states (~22 and ~40 kDa, respectively). The smearing in the dimer and tetramer bands of crosslinked AbrB (Lane B) suggest highly crosslinked species with differences in molecular weight, protein shape, and net charge from the attachment of different numbers of crosslinkers.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE analysis of Lane A) un-crosslinked full length AbrB and Lane B) crosslinked AbrB with SuDP reagent at 1:100 molar ratio.

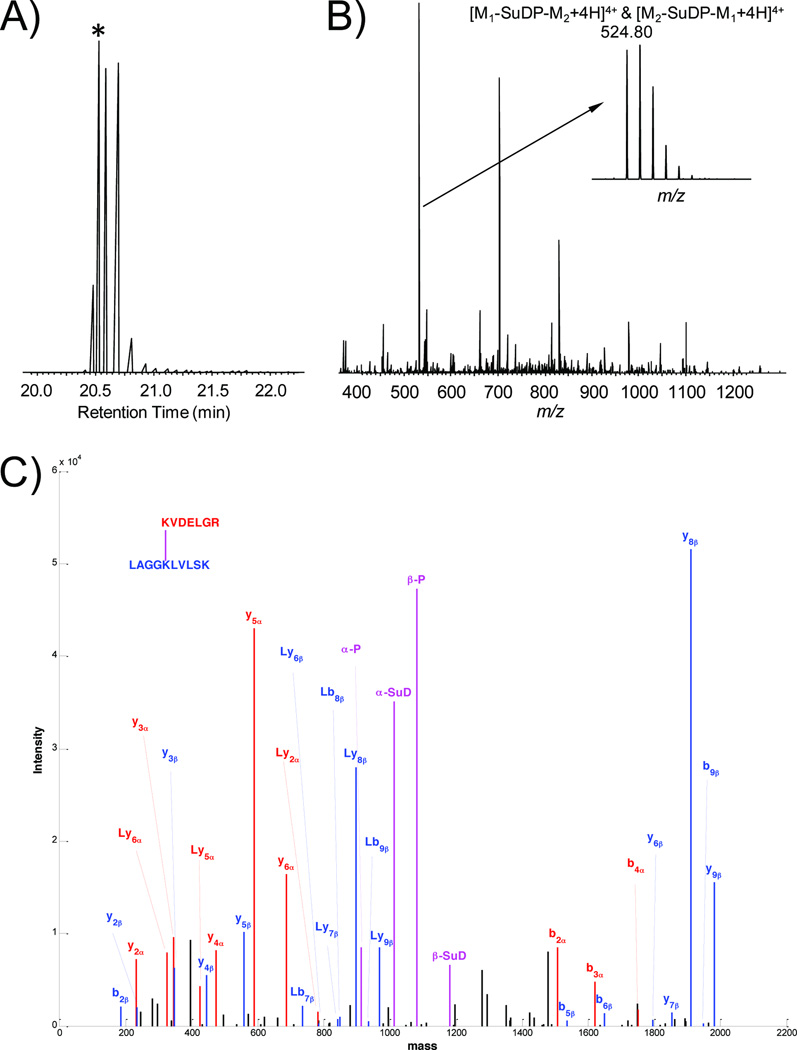

A list of inter-domain crosslinks is presented in Table 1 and an example of an inter-peptide crosslink is provided in Figure 2. In total, twenty two crosslinked species were observed, including (i) nine crosslinks in a single AbrBN homodimer (combined intra- and inter-domain crosslinks), (ii) three crosslinks in a single AbrBC homodimer (combined intra- and inter-domain crosslinks) and (iii) ten inter-domain crosslinks spanning from AbrBN to AbrBC. Of the ten AbrBN to AbrBC crosslinks seven were used in organizing the domains with measured distances of 10Å-22.1Å (Table 1). The remaining three crosslinks (K2-K71, K49-K71, K49-K76) involve peptides of the highly unstructured region of AbrBN (K2) and the especially flexible domain linker (K49). Since those portions of the protein are very dynamic, these crosslinks could not be employed to reliably define distances.

Table 1.

Interdomain crosslinks of AbrB by SuDP labeling.

| Peptide 1 | Mass Calculated (Da) |

Mass Measured (Da) |

Peptide 2 | Mass Calculated (Da) |

Mass Measured (Da) |

Crosslink (Cα- Cα) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILLK*K | 613.4526 | 613.4543 | LAGGK*LVLSK | 984.6336 | 984.6361 | K46-K71 |

| K*VDELGR | 815.4501 | 815.4518 | LAGGK*LVLSK | 984.6331 | 983.6276 | K9-K71 |

| GSHMK*STGIVR | 1171.6131 | 815.4518 | LAGGK*LVLSK | 984.6331 | 984.6334 | K2-K71 |

| TLGIAEK*DALEIYVDDEK | 2021.0204 | 2020.0180 | LAGGK*LVLSK | 984.6331 | 984.6338 | K31-K71 |

| YK*PNM#TC^QVTGEVSDDNLKLAGGK | 2640.2522 | 2640.2711 | LAGGK*LVLSK | 984.6331 | 984.6341 | K49-K71 |

| YK*PNMTC^QVTGEVSDDNLKLAGGK | 2624.2574 | 2624.2712 | LVLSK*EGAEQIISEIQNQLQNLK | 2594.4278 | 2594.4534 | K49-K76 |

| TLGIAEK*DALEIYVDDEK | 2021.0204 | 2021.0312 | LVLSK*EGAEQIISEIQNQLQNLK | 2594.4278 | 2594.4534 | K31-K76 |

| IILK*K | 613.4526 | 613.4580 | YKPNMTC^QVTGEVSDDNLK*LAGGK | 2624.2574 | 2624.2593 | K46-K66 |

| K*VDELGR | 815.4501 | 815.4513 | YKPNMTC^QVTGEVSDDNLK*LAGGK | 2624.2573 | 2623.2565 | K9-K66 |

| K*VDELGR | 815.4501 | 815.4514 | LVLSK*EGAEQIISEIQNQLQNLK | 2594.4278 | 2594.4491 | K9-K76 |

Lysine involved in crosslinking

Carboxamidomethylation of Cys

Oxidation of Met

Figure 2.

LC/MSn analysis of an AbrB inter-peptide crosslink KVDELGR-LAGGKLVLSK. (A) The extracted chromatograph of the crosslink precursor m/z 524.80. The each peak maximum corresponds to the MS scan with the intervening time between them corresponding to the tandem MS scans. (B) The MS spectrum containing the crosslink precursor. The time point of the selected MS spectrum is indicated by the asterisk in panel (A). In this example, the crosslinked precursor is the most abundant ion in the spectrum, which is enlarged to illustrate its isotopic distribution. It is a +4 charged ion with a monoisotopic m/z value of 524.80, where M1 is KVDELGR (Peptide 1) and M2 is LAGGKLVLSK (Peptide 2) as listed in Table 1. (C) The MS2 product ion spectrum of crosslink precursor. The product ion spectrum is reconstructed based on the deconvoluted neutral monoisotopic masses generated by CXLinkS using the raw data and is manually inspected to verify the crosslink identification. The product ions from peptide alpha KVDELGR (M1), peptide beta LAGGKLVLSK and the crosslinker fragmentation are shown in red, blue and magenta, respectively. The letter L indicates the remaining portion of the cleaved crosslinker with respect to each peptide fragment ion. Each individual linked peptide (magenta) is subjected to LC/MS3 CID fragmentation for sequence identification (MS3 data not shown).

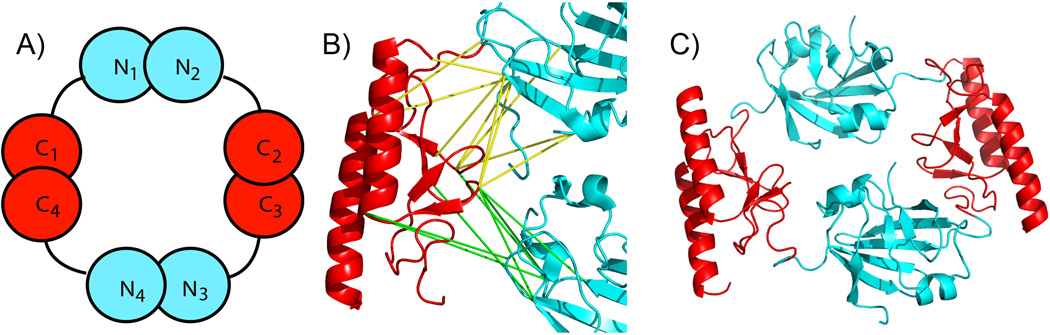

Usable restraints were used in PyMOL to model AbrB by manually positioning the AbrBC NMR structure relative to AbrBN based on the maximum distance constraint of 23.9Å using SuDP reagent (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrödinger, LLC). For each pair of crosslinked lysyl groups, there are eight possible crosslinks due to AbrB’s tetrameric nature. However, four of the eight crosslinks can be eliminated since there are two faces to the N-terminal domain, with the one, more distant face, exceeding the crosslinking distance. This is illustrated schematically in Fig. 3A. As shown, the C-terminal domain C1 can have crosslinks to residues in both N1 and N4 N-terminal domains, but crosslinks to N2 and N3 N-terminal domains would be disallowed. The remaining four allowed crosslinks are used to orient the AbrBC (red) to AbrBN (cyan) to satisfy the maximal distance constraints. The suite of crosslinks used between domains is shown in Fig. 3B and the subsequent fully assembled tetrameric AbrB structure is shown in Fig. 3C.

Figure 3.

A) AbrB tetramer with corresponding monomers and domains labeled. B) Cartoon representation of crosslinks formed by C-terminal lysine residues (red) to lysine residues of N-terminus (cyan) of AbrB by SuDP reagent where yellow and green lines represent crosslinks to neighboring N-termini. C) Assembled AbrB structure based on crosslinks detected in Table 1.

In summary, we have shown that chemical crosslinking in conjunction with mass spectrometry can be used to accurately elucidate domain organization in a protein where the individual, independent domain structures are known, but cannot easily be connected by other means (e.g. X-ray crystallography and NMR). The crosslinking data facilitated spatial placement of the N- and C-terminal domains of AbrB based on the maximal distance constraints using SuDP crosslinking reagent. The long-range distance constraints provided by this method successfully enabled us to obtain a model of full tetrameric AbrB.

Highlights.

The transition state regulator AbrB from Bacillus subtilis exists as a functional tetramer

Inherent dynamics makes AbrB extremely challenging to investigate from conventional methods

Chemical crosslinking and MS analysis to generate a model of full length AbrB from B. subtilis

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant NIH GM055769 (JC) and DOD DMRDP program (W81XWH-11-2-0115) (JC). Part of this work was supported by a Major Research Instrumentation grant from the National Science Foundation (DBI-1126244). We thank the research agencies of North Carolina State University and the North Carolina Agricultural Research Service for continued support of our bioanalytical mass spectrometry research.

Abbreviations

- SuDP

disuccinimidyl-succinamyl-aspartyl-proline

- PRE

paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- FRET

Förster resonance energy transfer

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- LC/MSn

multi-stage liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Andrew L. Olson, Email: alolson@ncsu.edu.

Fan Liu, Email: fliu4@ncsu.edu.

Ashley T. Tucker, Email: attucker@ncsu.edu.

Michael B. Goshe, Email: michael_goshe@ncsu.edu.

John Cavanagh, Email: john_cavanagh@ncsu.edu.

References

- 1.Robinson CV, Sali A, Baumeister W. The molecular sociology of the cell. Nature. 2007;450:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nature06523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Ramelot TA, McCarrick RM, Ni S, Feldmann EA, Cort JR, Wang H, Ciccosanti C, Jiang M, Janjua H, Acton TB, Xiao R, Everett JK, Montelione GT, Kennedy MA. Combining NMR and EPR Methods for Homodimer Protein Structure Determination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11910–11913. doi: 10.1021/ja105080h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ha T. Single-Molecule Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer. Methods. 2001;25:78–86. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hubbell WL, Cafiso DS, Altenbach C. Identifying conformational changes with sitedirected spin labeling. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2000;7:735–739. doi: 10.1038/78956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rinner O, Seebacher J, Walzthoeni T, Mueller L, Beck M, Schmidt A, Mueller M, Aebersold R. Identification of cross-linked peptides from large sequence databases. Nat Meth. 2008;5:315–318. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinz A. Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein?protein interactions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2006;25:663–682. doi: 10.1002/mas.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderblom EJ, Bobay BG, Cavanagh J, Goshe MB. Tandem mass spectrometry acquisition approaches to enhance identification of protein-protein interactions using low-energy collision-induced dissociative chemical crosslinking reagents. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2007;21:3395–3408. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu F, Goshe MB. Combinatorial Electrostatic Collision-Induced Dissociative Chemical Cross-linking Reagents for Probing Protein Surface Topology. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:6215–6223. doi: 10.1021/ac101030w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu F, Wu C, Sweedler JV, Goshe MB. An enhanced protein crosslink identification strategy using CID-cleavable chemical crosslinkers and LC/MSn analysis. Proteomics. 2012;12:401–405. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strauch MA, Ballar P, Rowshan AJ, Zoller KL. The DNA-binding specificity of the Bacillus anthracis AbrB protein. Microbiology. 2005;151:1751–1759. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27803-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson LM, Vaughn JL, Strauch MA, Bobay BG, Thompson R, Naylor S, Cavanagh J. Macromolecular Assembly of the Transition State Regulator AbrB in Its Unbound and Complexed States Probed by Microelectrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2002;306:222–227. doi: 10.1006/abio.2002.5704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips ZEV, Strauch MA. Role of Cys54 in AbrB multimerization and DNA-binding activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2001;203:207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bobay BG, Benson L, Naylor S, Feeney B, Clark AC, Goshe MB, Strauch MA, Thompson R, Cavanagh J. Evaluation of the DNA Binding Tendencies of the Transition State Regulator AbrB. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16106–16118. doi: 10.1021/bi048399h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bobay BG, Andreeva A, Mueller GA, Cavanagh J, Murzin AG. Revised structure of the AbrB N-terminal domain unifies a diverse superfamily of putative DNA-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5669–5674. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coles M, Djuranovic S, Söding J, Frickey T, Koretke K, Truffault V, Martin J, Lupas AN. AbrB-like Transcription Factors Assume a Swapped Hairpin Fold that Is Evolutionarily Related to Double-Psi β Barrels. Structure. 2005;13:919–928. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson AL, Bobay B, Melander C, Cavanagh J. 1H-13C, and 15N resonance assignments and secondary structure prediction of the full-length transition state regulator AbrB from Bacillus anthracis . Biomolecular NMR Assignments. 2012;6:95–98. doi: 10.1007/s12104-011-9333-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soderblom EJ, Goshe MB. Collision-Induced Dissociative Chemical Cross-linking Reagents and Methodology: Applications to Protein Structural Characterization using Tandem Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:8059–8068. doi: 10.1021/ac0613840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sullivan DM, Bobay BG, Kojetin DJ, Thompson RJ, Rance M, Strauch MA, Cavanagh J. Insights into the Nature of DNA Binding of AbrB-like Transcription Factors. Structure. 2008;16:1702–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]