Abstract

The Wisconsin Twin Research Program comprises multiple longitudinal studies that utilize a panel recruited from statewide birth records for the years 1989 through 2004. Our research foci are the etiology and developmental course of early emotions, temperament, childhood anxiety and impulsivity, autism, sensory over-responsivity, and related topics. A signature feature of this research program is the breadth and depth of assessment during key periods of development. The assessments include extensive home and laboratory-based behavioral batteries, recorded sibling and caregiver interactions, structured psychiatric interviews with caregivers and adolescents, observer ratings of child behavior, child self-report, cognitive testing, neuroendocrine measures, medical records, dermatoglyphics, genotyping, and neuroimaging. Across the various studies, testing occasions occurred between 3 months and 18 years of age. Data collection for some aspects of the research program has concluded and, for other aspects, longitudinal follow-ups are in progress.

Keywords: twins, longitudinal, emotions, temperament, child psychopathology, autism, sensory

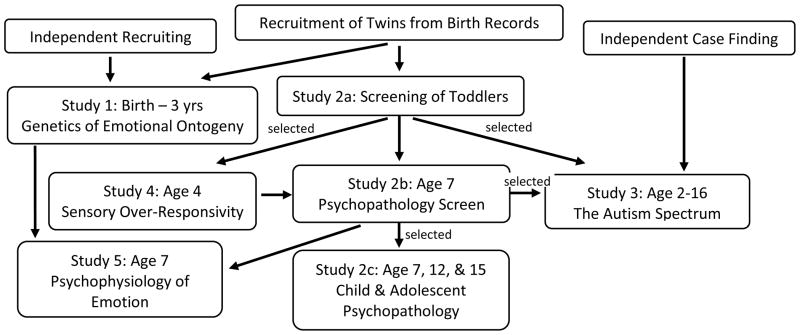

The Wisconsin Twin Research Program partnered with the Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services, State Section of Vital Records, in the early 1990s to develop a panel of all twins born in the state of Wisconsin, United States (Goldsmith et al., 2007; Lemery-Chalfant et al., 2006). The initial goal of this partnership was to harness the strength of a population-based sample to address public health questions concerning the nature and sources of emotional individuality and risk for anxiety and behavioral disorders. With the support of twins and their families, five research projects have been conducted; these projects span the periods of human development from infancy through late adolescence (see Figure 1). The research is primarily conducted at the Waisman Center at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, http://www.waisman.wisc.edu/twinresearch/. The Waisman Center is a multidisciplinary center with research, training, clinical, and outreach programs. Operationally, the Wisconsin Twin Research Program is part of the Social and Affective Sciences Group in the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center; some parts of the program are conducted at the Department of Psychology, also at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Fig. 1. Wisconsin Twin Research Design.

Note. Parent and sibling data were collected in studies 1–4.

The project is directed by Hill Goldsmith and co-directed by Kathryn Lemery-Chalfant, (now at Arizona State University). The project involves several key collaborators: (1) scientists affiliated with the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior, directed by Richard Davidson and including Andrew Alexander; (2) scientists and staff associated with the longitudinal Wisconsin Study of Families and Work, which is directed by Marilyn Essex and which shares many assessments with the twin panel; (3) neuroendocrinology specialists, notably Ned Kalin and Elizabeth Shirtcliff (now at the University of New Orleans); and (4) many graduate students and postdoctoral fellows.

A wide range of research methodologies are employed, including extensive home and laboratory-based behavioral batteries, video-recorded sibling and caregiver interactions, structured psychiatric interviews with caregivers and adolescents, observer ratings of child behavior, child self-report, cognitive testing, neuroendocrine measures, medical records, dermatoglyphics, genotyping, and neuroimaging. Key variables are assessed from a multi-method perspective, including some combination of the child’s self-ratings, ratings from one or both parents, observational ratings from two child examiners, behavioral performance scores from two or more emotion-eliciting tasks, diagnostic interviews, and co-twin ratings. Moreover, extensive behavioral, diagnostic, hormonal, and genetic data are collected on both twins, two parents, and siblings (regardless of genetic relationship).

Recruitment

Wisconsin is located in the north central United States. About 68% of the population of the state of Wisconsin lives inside metropolitan areas (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) although only one city has a population over 250,000. Residents of Wisconsin are predominantly of German (42.7%), Irish (10.9%), Polish (9.3%), and Norwegian (8.5%) ancestry (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). The population is largely Wisconsin native (95.8%). Although the state is known for agriculture, Wisconsin consistently ranked second in the United States for percent employment in manufacturing industries (17.2% in 2008) during the data collection period. Approximately 44% of families reside in small towns and villages (<10,000 population) or in rural areas. Zygosity was classified via parent rated questionnaire, review of placental pathology reports, consensus ratings by observation, and genotyping ambiguous cases. Additional characterization of the state population and twin panel was provided in earlier papers (Goldsmith et al., 2007) (Lemery-Chalfant et al., 2006). In brief, the entire Wisconsin twin panel is 50.5% female. Detailed characterization of twin birthweight and birth related events is provided elsewhere (Wagner et al., 2009; Keuler et al., 2011). Ethnic representation of twins is broadly representative of children born in the state with approximately 86% of the full twin panel reported by parents as non-Hispanic white. Socio-economic characterization of a longitudinal sample recruited over time is complex. Generally, participants represent a broad range of socioeconomic backgrounds with some restrictions at both lower and upper income levels. A practical requirement for participation biases the sample somewhat toward family stability and higher educational attainment. Recruitment and enrollment of twins ended in 2008.

The number of twin pairs contacted annually in Wisconsin from 1989 to 2004 are presented in Table 1 along with sample sizes at each testing occasion for the larger studies. The initial study, called the Genetics of Emotional Ontogeny (GEO), included a target sample within driving distance of Madison, Wisconsin and a satellite site at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee that recruited an all-minority subsample.

Table 1.

Wisconsin twin birth and twin pairs tested at each occasion by birth cohort

| Birth cohort | WI twin births (approx) | GEO 0 – 3yrs | 2yr screen | Child and adolescent psychopathology

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7yr screen | 7–8yr | 12–13yra | 14–15yra | ||||

| 1989 | 783 | -- | 27 | 19 | 10 | -- | -- |

| 1990 | 756 | -- | 29 | 19 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 1991 | 735 | 6 | 79 | 105 | 27 | 23 | 25 |

| 1992 | 813 | 16 | 186 | 219 | 114 | 89 | 92 |

| 1993 | 764 | 27 | 144 | 166 | 129 | 69 | 82 |

| 1994 | 813 | 42 | 113 | 153 | 52 | 74 | 82 |

| 1995/96b | -- | 38/30 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 1997 | 780 | 55 | 378 | 229 | 125 | 112 | 104 |

| 1998 | 831 | 103 | 335 | 270 | 109 | 94 | 77 |

| 1999 | 883 | 72 | 310 | 245 | 119 | 61 | 49 |

| 2000 | 940 | 83 | 309 | 270 | 139 | -- | -- |

| 2001 | 912 | 86 | 295 | 278 | 136 | -- | -- |

| 2002 | 913 | 119 | 329 | 24 | 20 | -- | -- |

| 2003 | 1,004 | 106 | 302 | 6 | 3 | -- | -- |

| 2004 | 1,005 | 1 | 425 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

|

| |||||||

| Total N: | 11,932 | 784 | 3,261 | 2,004 | 990 | 524 | 514 |

Note.

Testing in progress.

Birth records were unavailable to the project for these years.

A late adolescent follow-up of the child and adolescent psychopathology sample includes an fMRI component with monozygotic twins who have a history of chronic anxiety. A follow up of GEO participants at age 7–8 years included psychophysiology, n = 235. Multiple testing occasions were conducted with an autistic twin sample, n = 136.

Although some earlier studies recruited twins nearby the project’s laboratories, here we explain recruitment of the main, statewide sample. New birth cohorts were recruited every six months, approximately six months after the youngest twin pair in the cohort was born. The Wisconsin Department of Health and Family Services, State Section of Vital Records, screened for records of early deaths and provided the names and addresses of surviving twin pairs. Per our agreement with the State, we contacted families initially by mail with a letter, response interest form, and postage paid envelope. Six weeks after the initial recruitment letter, a second letter and response form was sent to families who had not responded with a $1.00 bill to remind and encourage parents to reply. Extensive internet searches of public records were conducted to find updated addresses for letters that were returned to us. By agreement with the State, attempts to recruit families were limited in scope. Of nearly 7,000 confirmed contacts, 87% responded favorably. Contact was maintained with a biannual newsletter, a website specifically tailored to research participants, a toll-free number, and magnets and pens featuring our contact information that were sent with a thank you card after research participation. The first assessment occasion for this statewide sample occurred when the twins were approximately two years of age and consisted of a 30 minute telephone interview and 30 minute questionnaire packet for two parents when possible. The second assessment occasion was scheduled for all families when the twins were approximately seven years of age and consisted of a 45 minute telephone interview concerned with health and mood and behavior symptoms.

Based on the age 2 and age 7 assessments of the full sample, we recruited families for different studies. One such study focused on autism and risk for autism and a much larger study covered a wide range of child and adolescent psychopathology. Thus far, all have included longitudinal components.

Below we summarize the five principal projects that have been undertaken using the twin panel. We begin with an overview of the assessment batteries for each project, and then we describe one recent illustrative result from each project.

Genetics of emotional ontogeny

The initial study, called the Genetics of Emotional Ontogeny (GEO), tracked emotional development in typically developing children from infancy until preschool (see Figure 1). As previously described (Goldsmith et al., 2007), 784 twin pairs were recruited from the greater Madison, Wisconsin, area through a variety of methods including state birth records, mothers of twins clubs, television publicity, birth announcements in newspapers, doctors’ offices, online searches, and referrals from participants (see Table 1). A satellite site at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee aimed to supplement the study with an all-minority subsample. Assessments were conducted at 3, 6, 9, 12, 19, 22, 25, 28, and 36 months of age. Assessment phases included extensive observational assessment of temperament and developmental milestones, psychophysiological measures, and parent-report measures to tap developmental trajectories of fear, anger, sadness, interest, contentment, and exuberance (Table 2). This specialized dataset offered a window into the early developmental processes and biological underpinnings of emotional individuality that contribute to mental health status later in childhood.

Table 2.

Principal instruments for the genetics of emotional ontogeny study

| Instrument | Child Age (mo) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child temperament and affective measures | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 18–30 | 36 |

| Infant Irritability Scale | T | |||||

| Rothbart or Goldsmith temperament questionnaires | T | T | T | T | T | |

| Age appropriate versions of the Laboratory-Temperament Assessment Battery | T | T | T | |||

| Behavioral tasks tapping social emotions | T | |||||

| Videotaped interaction & assays of positive affect and positive interactions | T | |||||

|

Non-affective domains of development

| ||||||

| Maternal Diaries | T | T | T | |||

| Psychophysiology measures | T | T | ||||

| Visual Expectation Paradigm | T | T | ||||

| Handedness assessment | T | T | ||||

| Assays of locomotor development | T | T | T | |||

| MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventory | T | T | ||||

| Pediatric Update Form | T | |||||

| Self awareness measures | T | |||||

|

Parent Personality and Symptoms

| ||||||

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale | T | |||||

| Positive and Negative Affect Scales | T | T | T | T | ||

| Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire | T | |||||

|

Family Stress, Parenting, Relationships

| ||||||

| Video-recorded feeding & bathing sessions | T | |||||

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment | T | T | ||||

| Child Rearing Practices Report | T | T | ||||

| NCAST task | T | T | ||||

| Family Expressiveness Questionnaire | T | T | T | |||

| Parenting Stress Inventory | T | T | T | |||

| Sibling Conflict Questionnaire | T | |||||

| Parental dyadic interaction measures | T | |||||

|

Prenatal and Neonatal

| ||||||

| Palm & finger print asymmetries | ||||||

| Neonatal Morbidity Scale | ||||||

| Obstetrical & Neonatal Complications Scales | ||||||

Note. At some ages only relevant portions of instruments were used. Zygosity was classified via parent rated questionnaire, review of placental pathology reports, consensus ratings by observation, and genotyping ambiguous cases.

In one recent example of this work, we identified normative and atypical developmental trajectories of fear development between the 6 and 36 month assessments (Brooker et al., 2012). Maternal and paternal ratings of infants’ social fear at 6, 12, 22, and 36 months of age were used to classify children according to latent trajectories of change in stranger fear over time. Four distinct profiles of stranger fear development emerged: slow increases in stranger fear, steep increases in stranger fear, stable high levels of fear, and initially high but decreasing levels of stranger fear between 6 and 36 months of age. Profiles of stranger fear, which were moderately heritable, predicted observed fearfulness during laboratory assessments at 6 and 12 months of age. Moreover, stable, high levels of fear from 6 to 36 months of age uniquely predicted greater levels of behavioral inhibition at age 3 years, a purported marker of anxiety risk in young children.

In addition to identifying outcomes related to individual differences in early fear development, we identified mechanisms in early development that differentiated infant trajectories of stranger fear. For example, muted respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA) suppression during a social challenge and high levels of maternal stress reactivity and negative affect were associated with high, stable levels of stranger fear during infancy (Brooker et al, under review).

Child and adolescent psychopathology

The child and adolescent psychopathology project began with a community-based sample of all twins born in Wisconsin and included five testing occasions between toddlerhood and adolescence (see Figure 1). We broadly characterized child symptoms and a variety of risk factors. The measurement design included multiple methods and informants, prenatal and neonatal variables recorded from medical records, dermatoglyphics, multiple neuroendocrine measures including basal cortisol on all family members, reactive cortisol measures, testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) at age 12–13, extensive home-based behavioral observations and measures of cognitive affective style, general cognitive performance measures, genotyping, measures of family stress and parenting, attributional style, peer measures, and child physical health (see Table 3). The project began with a behavioral screening of all toddlers born in Wisconsin. All families were contacted again for an age 7 behavioral screen that included the Health and Behavior Questionnaire symptom and impairment scales (Armstrong et al., 2003) Subsequent work targeted a subset of this community sample that was enriched for symptoms. If either twin was reported as higher than 1.5 standard deviation units on at least one of eight symptoms scales, the pair was selected for follow-up. If either twin was reported below the mean on all eight symptom scales, the pair was also selected for potential follow-up. The first follow-up occurred approximately 6–10 months after the age 7 screening. Families were recontacted at approximately ages 12 and 14 for follow-ups.

Table 3.

Instruments for the study of child and adolescent psychopathology

| Instrument | Child Age (yr) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child & Adolescent Psychopathology | 2 | 7 | 12 | 14 |

| Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assess (ITSEA) | T | |||

| Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI) | T | |||

| Child Depression Inventory (CDI) | T | T | ||

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DISC-IV) | T | T | ||

| Health & Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ) | T | T | T | |

| Obsessions & Compulsions Measure (OCD) | T | T | ||

| Observer ratings of DSM-IV symptoms and impairment | T | T | ||

| Sensory Responsivity Inventory (SRS) | T | |||

| Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) | T | T | ||

| Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) | T | T | ||

| Adult Sensory Profile | T | |||

| DISC Predictive Scales (DPS) | T | |||

|

Child Temperament

| ||||

| Revised Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ) | T | |||

| Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ) | T | |||

| Observer ratings of reactivity and regulation | T | T | ||

| Positive & Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | T | T | ||

| Child Temperament Assessment Battery (C-TAB) | T | |||

| Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ-R) | T | |||

| BIS/BAS Scales (BIS/BAS) | T | |||

|

Cognition

| ||||

| MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (short form) | T | |||

| Block Design subtest of the WISC-III | T | T | ||

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary-Revised (PPVT) | T | T | ||

| Digit Span subtest (WISC-III) | T | |||

| Behavioral Inhibition System Assessment | T | |||

| Emotion facilitation/lexical decision | T | |||

| Go/no-go Passive Avoidance Task | T | |||

| Picture-Word Stroop | T | |||

| Color-Work Stroop | T | |||

|

Attributional Style

| ||||

| Children’s Attributional Styles Questionnaire-Revised (CASQ-R) | T | |||

| Children’s Rejection Sensitivity Questionnaire (CRSQ) | T | |||

| Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ); | T | |||

| Hostile Attributions | T | |||

|

Biological measures

| ||||

| Multi-day basal cortisol for all family members, 3x/day over 3 days | T | T | ||

| Reactive cortisol for twins, 3x over a 4 hour in-home assessment | T | |||

| Genotyping twins, both parents, and siblings | T | |||

| DHEA and testosterone assays, other puberty measures | T | |||

| Palm & finger print asymmetries | T | |||

| Neonatal Morbidity Scale (NMS) | T | |||

| Obstetrical & Neonatal Complications Scales | T | |||

|

Family Personality and Symptom measures

| ||||

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for parents | T | T | ||

| Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) for parents | T | T | ||

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) for parents | T | T | ||

| Health & Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ) for nontwin siblings | T | T | ||

| Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) for parents | T | T | ||

|

Family Stress & Parenting

| ||||

| Child Rearing Practices Report (CRPR) | T | T | T | |

| Confusion, Hubbub, & Order Scale (CHAOS) | T | T | ||

| Differential Treatment (SIDE) | T | T | ||

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS) | T | T | ||

| Family Assessment Device (FAD) | T | |||

| Family Conflict Scale (FCS) | T | T | ||

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) | T | T | ||

| Life Experiences Survey (LES) | T | T | ||

| Living Environment Observation Scale (HOME) | T | T | ||

| Parenting Stress Index (PSI) | T | T | T | |

| Behavioral Management Self Assessment (BMSA) | T | T | ||

| Discipline Measure | T | T | ||

| Parent/Twin Triadic Interactions (coded from videotape) | T | |||

| Religiosity Questionnaire | T | |||

| Twin Inventory of Relationships and Experiences (TIRE) | T | T | ||

| Parental Monitoring | T | |||

|

Peer and Contexts

| ||||

| Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI) | T | |||

| Health & Behavior Questionnaire Peer and Prosocial Scales (HBQ) | T | T | T | |

| Sibling Relationship Questionnaire (SRQ) | T | T | ||

| Twin Dyadic Interactions (coded from videotape) | T | |||

| Network of Relationships Inventory (NRI) | T | |||

| School Success Inventory | T | |||

Note. Zygosity was assessed independently evaluated with parent rated questionnaire, observer ratings, review of placental pathology reports, and genotyping. Magnetic resonance imaging is included in a late adolescent follow up of MZ twin pairs with a history of chronic anxiety.

A set of findings concerning biological stress indexed by cortisol demonstrated that genetic and environmental factors differentially affect cortisol levels across the day (Van Hulle et al., 2012). Morning cortisol level and morning-to-afternoon slope were modestly heritable (h2 = .31), while afternoon and evening cortisol level and afternoon-to-evening slope were largely influenced by shared family environment (c2 ranged .50 to .70) (Van Hulle et al., 2012). In addition, familial environmental influences on afternoon cortisol were shared by parents and offspring (Schreiber et al., 2006) Basal cortisol profile, a combination of morning level and diurnal slope, predicted behavior problems in boys. Boys with a dysregulated HPA axis, as evidenced by cortisol that started and remained high across the day or cortisol that continued to decline into the afternoon and evening, had a higher number of depressive symptoms compared to boys with a typical diurnal profile (Van Hulle et al., 2012).

The autism spectrum

The primary goals of this study are to quantify genetic contributions to autism spectrum conditions, assess the Broader Autism Phenotype in family members, and characterize co-occurring but non-diagnostic behavior problems, such motor dyspraxia. The studies of the autism spectrum began with all twins born in the state of Wisconsin who participated in a toddler assessment (see Figure 1). Published analyses first focused on autism screener scores, and the genetic variance associated with them (Stilp et al., 2010). In addition to autistic individuals identified via the screening based on birth records, another set of participants was referred through case finding. The primary strategy for case finding was to solicit eligible families through a newsletter mailing to approximately 7,000 families with twins born in Wisconsin, which, we believe, yielded a more representative group than using clinic referrals. Using these methods, 191 twin pairs were identified for follow up during the preschool period. The preschool assessment was administered to 129 twin pairs and included measures of physical similarities and differences, as well as autism screening items administered via a telephone interview with the primary caregiver (see Table 4). After considering families with at least one twin with an elevated level of autistic features (at least 66% of the given Autism Spectrum Disorder cutoffs for the Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino, 2002) and/or the Social Communication Questionnaire (Rutter et al., 2003) and inclusion and exclusion criteria, 80 twin pairs (62%) were selected for follow up and 73 were assessed in person with an extensive battery of assessments. Using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (Lord et al., 2001) and Social Communication Questionnaire for autism classification (96% agreement with existing community diagnoses), the final sample included 54 twin pairs (23 monozygotic) with at least one member qualifying for an Autism Spectrum designation. About three-quarters of monozygotic--but only about a third of dizygotic co-twins--were concordant for autism spectrum disorder on a probandwise basis.

Table 4.

Instruments for the study of the autism spectrum

| Instrument |

|---|

|

Toddler screening

|

| Composite of existing autism screeners |

| Short Sensory Profile |

| Revised Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ) |

| MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (short form) |

| Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assess (ITSEA) |

| Project designed measure of developmental milestones |

|

Preschool screening

|

| Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ) |

| Social Responsiveness Questionnaire (SRS) |

| Zygosity Questionnaire |

| Medical Questionnaire |

|

In-person follow up study, age 4–20

|

| • Child measures |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) |

| Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ) |

| Berkeley Puppet Interview (BPI) |

| Short Sensory Profile |

| Child Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ) |

| Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire (EATQ) |

| Observer ratings of reactivity and regulation |

| Speech tasks: Syllable Repetition Task, Lexical Stress Task, Emphatic Stress Task, Compound Word Task, Non-Word Repetition Task |

| Kaufman Speech Praxis Test for Children |

| Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals III/Pre-school |

| Test for Reception of Grammar 2 (TROG) |

| Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination-3: Praxis Test section |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 3 (PPVT) |

| Leiter International Performance Scales-Revised |

| • Parent and family measures |

| Center/Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale |

| Profile of Mood States |

| Dyadic Assessment Scale |

| Sensory Profile (of parents) |

| Family Relationship Index |

| COPE Inventory |

| Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) |

| • Miscellaneous |

| DNA, dermatoglyphics, digit (finger) lengths, diurnal cortisol |

| Intervention history-standardized measure for autism developed for the CPEA studies |

| Hospital/physician records of pregnancy, labor/delivery, and pediatric care |

The follow-up battery of assessments included the Short Sensory Profile (Dunn, 1999), a parent report measure with a standardized (based on norms) threshold score that indicates a probable or definite atypicality. Despite widespread recognition that an increase in sensory symptoms co-occurs with autism, studying patterning of sensory symptoms within autism families is rare. In our sample, over 90% of the autistic twins and about a third of non-autistic twins crossed the threshold of a probable or definite sensory difference (Goldsmith & Meyer, 2012). Non-autistic twins had fewer sensory symptoms than their autistic co-twins, but were elevated compared to typical samples, suggesting family aggregation. Monozygotic twins were substantially more concordant for categorical sensory atypicality (i.e., on the same side of the threshold score) than were dizygotic twins. Further, dizygotic twins were no more similar to one another in sensory symptoms than were individual twins to their non-twin siblings. This latter finding both supports the validity of the twin method for inferring genetic influences and suggests that the shared prenatal environment is not a major influence.

Sensory over-responsivity

The study of sensory over-responsivity (SOR) extended beyond autism. This work began with the community-based sample of all twins born in Wisconsin and included four testing occasions between toddlerhood and early adolescence (see Figure 1). The focus of this study was characterization of auditory and tactile SOR, stability of SOR, and examination of a variety of clinical outcomes for individuals with early and chronic SOR. Data collection was entirely embedded in the toddler screen and later largely imbedded in the study of child and adolescent psychopathology (see Table 1). A separate list of SOR instruments is presented in Table 5. A subsample of 80 twin pairs with reported high SOR were studied in person at age 4 in an age-matched control design.

Table 5.

Instruments for the study of sensory over-responsivity

| Instrument | Child Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2yr | 7yr | 12yr | |

| Infant-Toddler Social & Emotional Assess (ITSEA) | T | ||

| Revised Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire (TBAQ) | T | ||

| Sensory Checklist | T | T | |

| Sensory Responsivity Inventory (SRS) | T | T | |

| Adult Sensory Profile | T | ||

Note. Additional measures of co-occurring physical health and behavior problems are collected and described in the child and adolescent psychopathology study. A subsample at age 4 included additional in-person sensory measures.

A sample of 970 individuals was used to investigate whether individuals who screened positive for SOR also experience other childhood behavior disorders. A majority (58.2%) of individuals who screened positive for SOR did not qualify for a diagnosis on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC; Schwab-Stone et al., 1996; Van Hulle et al., 2011) Moreover, a majority (68.3%) of individuals who qualified for a DISC diagnosis did not screen positive for SOR. Thus, evidence for some distinctiveness for SOR emerged. In a dimensional approach, multivariate twin models revealed that the modest covariation between SOR and DISC symptoms could be entirely accounted for by common underlying genetic effects. Although cases of SOR and childhood psychiatric diagnoses appear as categorically distinct, with some notable comorbidity, common genetic etiology is highly implicated.

Psychophysiology of emotion

The psychophysiology of emotion study was largely a follow-up study of the normative GEO sample (see Figure 1). Recruitment was based both on internal records of families who participated in the GEO study and supplemented by families who participated in the age 7 behavior screen. Assessments were completed with 235 twin pairs and included a laboratory visit with comprehensive psychophysiological assessments, including baseline and reactive measures of cortisol, DNA, electroencephalography (EEG), startle, heart rate, respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA), and pre-ejection period (PEP), In addition, we administered home observation-based assessments of temperament and parent-report questionnaires. The laboratory and home assessments were approximately two weeks apart.

One line of results focused on context-inappropriate anger, or anger elicitation in contexts that were designed to be positive in nature (e.g., playing a game with a balloon) (Locke et al., 2007) Although the expression of context-inappropriate anger was relatively rare overall, its presence in boys was associated with lower levels of morning cortisol and less variation (i.e., flatter slopes) in diurnal cortisol over the course of the day. This work was consistent with previous studies suggesting that context inappropriate anger and other symptoms of externalizing problems are linked to a blunted pattern of diurnal cortisol.

We have also studied the biological underpinnings of positive affect. Patterns of nonlinear change in EEG activity during positive-affect-eliciting tasks were associated with lateralized activity in the frontal lobes (Light et al., 2009). For example, children who expressed higher levels of positive affect also displayed greater left frontal activation (relative to right frontal activation). In contrast, children who displayed general contentment across the episode exhibited decreasing left frontal activation over time (or increasing right frontal activation). Additional work has also associated right frontal activation with empathic concern and suggested that dynamic patterns of lateralized activity in the frontal lobes could predict differences between two types of positive empathy (i.e., empathic happiness and empathic cheerfulness) (Light et al., 2009).

Future directions

This set of twin studies is well staged to address novel research questions. The U.S. NIMH Strategic Plan calls for a line of research to study mental health disorders from a dimensional approach with observable behavior and neurobiological measures. The design of the Wisconsin twin studies is consonant with this dimensional, psychobiological approach, and offers a developmental perspective on the issues. Moreover, the inclusion of individuals below the diagnostic threshold and unaffected co-twins may address other questions in the dialogue about dimensional properties of psychopathology. The broad characterization of the samples invites investigations of selected subsamples. For instance, use of a monozygotic twin difference approach to chronic anxiety with structural and functional neuroimaging is underway, as is a study of risk factors for adolescent obesity. A wide range of future studies may benefit from our rich phenotyping during early development. Interest in collaboration is encouraged.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH059785, R01-MH069793, R37-MH050560), the Wisconsin Center for Affective Science (P50-MH069315), a Conte Neuroscience Center (P50-MH084051), the Wallace Research Foundation, and the National Alliance for Autism Research. Infrastructure support was provided by the Waisman Center via a core grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD003352). We owe special gratitude to Wisconsin twins and their families for their research participation.

Footnotes

This article has been accepted for publication and will appear in a revised form, subsequent to peer review and/or editorial input by Cambridge University Press/Australian Academic Press Ptv Ltd, in Twin Research and Human Genetics.

Contributor Information

Nicole L. Schmidt, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Carol Van Hulle, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Rebecca J. Brooker, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Lauren R. Meyer, University of Wisconsin–Madison

Kathryn Lemery-Chalfant, Arizona State University.

H. H. Goldsmith, University of Wisconsin–Madison

References

- Armstrong J, Goldstein L The MacArthur Working Group on Outcome Assessment. Manual for the MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire (HBQ 1.0) Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh.: MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Psychopathology and Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker R, Buss K, Lemery-Chalfant K, Aksan N, Davidson R, Goldsmith H. The development of stranger fear in infancy and toddlerhood: Normative development, individual differences, antecedents, and outcomes. 2012. Under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino J. The social responsiveness scale. Los Angeles CA: Western Psychological Services; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W. The Sensory Profile manual. San Antonio TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Meyer L. Sensory symptoms in autism families. International Meeting for Autism Research; Toronto, ON, Canada. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith H Hill, Lemery-Chalfant K, Schmidt NL, Arneson CL, Schmidt CK. Longitudinal analyses of affect, temperament, and childhood psychopathology. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2007;10:118–126. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keuler MM, Schmidt NL, Van Hulle C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Goldsmith HH. Sensory over-responsivity: prenatal risk factors and temperamental contributions. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2011;32:533–541. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182245c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemery-Chalfant K, Goldsmith HH, Schmidt NL, Arneson CL, Van Hulle CA. Wisconsin Twin Panel: Current directions and findings. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:1030–1037. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light SN, Coan JA, Frye C, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ. Dynamic variation in pleasure in children predicts nonlinear change in lateral frontal brain electrical activity. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:525–533. doi: 10.1037/a0014576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light SN, Coan JA, Zahn-Waxler C, Frye C, Goldsmith HH, Davidson RJ. Empathy is associated with dynamic change in prefrontal brain electrical activity during positive emotion in children. Child Development. 2009;80:1210–1231. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke RL, Davidson RJ, Kalin NH, Goldsmith HH. Children’s context inappropriate anger and salivary cortisol. Boston, MA: 2007. Mar, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S. Autism diagnostic observation schedule (ADOS) Los Angeles CA: Western Psychological Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social communication questionnaire. Los Angeles CA: Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber JE, Shirtcliff E, Van Hulle C, Lemery-Chalfant K, Klein MH, Kalin NH, Essex MJ, et al. Environmental influences on family similarity in afternoon cortisol levels: Twin and parent-offspring designs. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:1131–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab-Stone ME, Shaffer D, Dulcan MK. Criterion validity of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version 2.3 (DISC-2.3) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:878–888. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Census 2000 Summary File 3. 2000 Retrieved January 28, 2006, from http://factfinder.census.gov.

- Van Hulle CA, Shirtcliff EA, Lemery-Chalfant K, Goldsmith HH. Genetic and environmental influences on individual differences in cortisol level and circadian rhythm in middle childhood. Hormones and Behavior. 2012;62:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle C, Schmidt NL, Goldsmith HH. Is sensor over-responsivity distinguishable from childhood behavior problems? A phenotypic and genetic analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;53:64–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AI, Schmidt NL, Lemery-Chalfant K, Leavitt LA, Goldsmith HH. The limited effects of obstetrical and neonatal complications on conduct and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms in middle childhood. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30:217–225. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181a7ee98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]