Abstract

Clinical studies with immunotherapies for cancer, including adoptive cell transfers of T cells, have shown promising results. It is now widely believed that recruitment of CD4+ helper T cells to the tumor would be favorable, as CD4+ cells play a pivotal role in cytokine secretion as well as promoting the survival, proliferation, and effector functions of tumor-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Genetically engineered high-affinity T-cell receptors (TCRs) can be introduced into CD4+ helper T cells to redirect them to recognize MHC-class I-restricted antigens, but it is not clear what affinity of the TCR will be optimal in this approach. Here, we show that CD4+ T cells expressing a high-affinity TCR (nanomolar K d value) against a class I tumor antigen mediated more effective tumor treatment than the wild-type affinity TCR (micromolar K d value). High-affinity TCRs in CD4+ cells resulted in enhanced survival and long-term persistence of effector memory T cells in a melanoma tumor model. The results suggest that TCRs with nanomolar affinity could be advantageous for tumor targeting when expressed in CD4+ T cells.

Keywords: TCR, Adoptive T-cell therapy, Tumor targeting, Cancer immunotherapy, Melanoma

Introduction

It has been suggested that combined recruitment of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells to tumors can improve responses and generate long-term memory [1–3]. Infiltration of CD4+ T cells can provide a cytokine milieu favorable to inducing proliferation, survival, and effector function of CD8+ T cells within tumors as well as induce the activation of the innate immune system [4–8]. Additionally, CD4+ cells are capable of mediating cytotoxic activity, directly eradicating melanoma tumors, and can indirectly elicit tumor inhibition through IFN-γ-dependent effects on host cells [9–12]. CD4+ T cell activities at the site of a tumor could also provide an inflammatory environment that is favorable to the induction of human T-cell responses [13, 14].

A major problem with the recruitment of CD4+ T cells is that most tumors do not express class II MHC, thereby preventing direct recognition and activities associated with CD4+ T cells. To overcome this challenge, TCRs have been engineered with higher affinity for a class I tumor antigen, avoiding the requirement for CD8 co-receptors, and thereby mediating CD4+ T-cell activities [15–20].

Efforts to introduce αβ TCR genes into T cells activated ex vivo for cancer therapy have generated considerable excitement [21–26]. In the well-studied system that targets melanoma antigen MART-1/HLA-A2, two different TCRs have been used clinically, DMF4 and second-generation DMF5 [21, 22, 27]. Despite promising results with these TCRs, it is not yet clear whether even DMF5 represents an optimal TCR. For example, both DMF4 and DMF5 have relatively low affinities, with K d values of 170 and 40 μM, respectively [28], and while DMF5 promotes activity of CD4+ T cells, it is not clear whether the magnitude of this activity is optimal. In addition, it is not known whether TCRs with different affinities against class I MHC will mediate lineage commitment of different CD4+ subsets.

Experiments in vitro suggest that optimal co-receptor independent activation, for directing CD4+ T-cell activity by a class I pepMHC-specific TCR, occurs at higher affinities, in the range of 0.5–3 μM [18, 20]. However, affinities of most anti-tumor TCRs have not been measured, largely due to problems with the expression of soluble TCRs and the normally very low affinity of TCRs for their cognate pepMHC antigens. In addition, recent evidence suggests that the behavior of T cells in vivo may not be completely predictable by activities in vitro [29, 30]. The activity of TCR-transduced CD4+ T cells in vivo, with well-characterized TCRs, requires study.

To examine the role of TCR affinity in adoptive T-cell therapies, we took advantage of the well-studied 2C TCR, specific for class I MHC Kb bound to foreign peptide SIYRYYGL (SIY, K d = 30 μM), and its high-affinity TCR variant called m33 (K d = 30 nM) [31]. Our recent results showed that CD8+ T cells with the m33 TCR were deleted in vivo, whereas CD4+ T cells with the m33 TCR persisted, and were capable of mediating an anti-tumor response [30]. Here, we show that the higher affinity TCR m33 was superior to the lower affinity 2C TCR in mediating effective destruction of B16 melanomas by CD4+ T cells. While the 2C-transduced CD4+ T cells mediated an effect against antigen-bearing tumors, antigen-loss variants were responsible for reoccurrence in every case. The m33-transduced CD4+ T cells not only mediated a stronger response, as measured by delayed tumor growth and/or elimination of antigen-loss variants, but some mice also generated a long-term response. Furthermore, CD4+ T cells in these mice persisted, and they mediated an antigen-specific memory response against the B16-SIY melanomas. These results indicate that there are benefits to using TCRs with affinities that are higher than current TCRs (e.g., DMF5) in adoptive CD4+ T-cell therapies.

Materials and methods

Mice and tumor cell lines

Experiments were performed with C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 Rag1 −/− mice, 2–5 months of age, purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were maintained as colonies and housed in the animal facilities at the University of Illinois. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Illinois. Murine melanoma B16-F10 cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassa, VA, USA). B16-SIY was derived from B16-F10 cells engineered to express green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a fusion protein with SIYRYYGL (SIY) [54, 55]. Cell lines were cultured in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 5 mM HEPES, 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1.3 mM l-glutamine, 50 μM 2-ME, penicillin, and streptomycin at 37 °C and 5 % CO2.

Interferon gamma treatment and flow cytometry of melanoma cells

Melanoma cells were cultured at a density of 7 × 105 cells per well (6-well plate), with or without 10 ng/mL interferon gamma (IFN-γ, eBioscience) for 24 h. Cells were stained with anti-Kb (B8.24.3 monoclonal antibody) or soluble biotinylated single-chain TCR m67 to detect SIY peptide bound to H2-Kb on the surface of tumor cells [32]. After 1 h, cells were washed, and streptavidin–allophycocyanin (Invitrogen) was added for 30 min. Cells were analyzed on an Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer.

51Chromium T-cell killing assay

Target cells labeled with 51Cr (150 μL of 2 mCi/mL) were incubated with mock, 2C WT- or m33 TCR-transduced CD4+ T cells at 5:1 and 20:1 effector to target (E/T) ratios for 4 h. Supernatants were assayed using a Beckman gamma counter; specific lysis was calculated using the formula: [(sample chromium counts − spontaneous chromium release)/(maximum chromium counts − spontaneous chromium release)] × 100. Chromium release from B16-SIY melanoma cells incubated with mock CD4+ T cells was used to calculate percent specific B16-SIY cell lysis.

Melanoma tumor model and T-cell transfer

B16-F10 or B16-SIY melanoma cells were harvested and washed twice with Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Cellgro Mediatech Inc). Shaved mice received 1–1.5 × 106 tumor cells subcutaneously into the right flank (unilateral tumor) or right and left flank (bilateral tumors) of Rag1 −/− mice under isoflurane (Baxter) inhalation anesthesia. For adoptive T-cell transfer, an average of 7 × 106 mock- and TCR-transduced CD4+ or CD8+ T cells harvested from 24-well plates and washed twice with HBSS were injected in the tail vein of mice either 5 or 10 days (established tumor model) following tumor inoculation. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor length and width with a caliper every 2 days. Tumor volume was estimated as (length × (width)2)/2.

Preparation of melanoma tumors ex vivo

For isolation of single-cell suspensions to detect antigen-loss variants, implanted B16-SIY melanoma tumors were harvested, sectioned, and incubated with 300 Collagenase Digestion U/mL (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 mg/mL Dispase (Roche) for 40 min at 37 °C. After incubation, 0.002 MU/mL DNase (Calbiochem) was added for further dissociation using gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell suspensions were pipetted through 100 μm filters and centrifuged at 300 × g for 10 min. Single-cell suspensions were cultured for 6–7 days, treated with IFN-γ, and stained with TCR m67.

Analysis of lymphocyte cell surface phenotypes

Single-cell suspensions from lymph nodes or spleens were dual-stained with AlexaFluor647-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD4 Ab (Clone RM4-5, BD Pharmingen) in combination with either PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD62L Ab (Clone MEL-14, BD Pharmingen), AlexaFluor488-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD127 Ab (Clone SB/199, BD Pharmingen), or PE-conjugated mouse anti-mouse Vβ8.1/8.2 Ab (Clone MR5-2, BD Pharmingen). For isotype controls, cells were stained with PE-conjugated rat IgG2a, AlexaFluor488-conjugated rat IgG2b, or PE-conjugated mouse IgG2a. After washing, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Accuri C6).

TCR-gene retroviral transduction of primary murine T cells

Platinum-E (Plat-E) retroviral packaging cells were transfected with 2C TCR or m33 TCR genes cloned into the pMP71 vector (from myeloproliferative sarcoma virus, MPSV) as described [30]. Viral supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection, filtered with a 0.45 μm syringe filter, and 50 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 added per 6 mL of viral supernatant. For transductions, CD8+ or CD4+ T splenocytes from C57BL/6 mice were negatively selected by magnetic sorting using the Mouse CD8α+ or CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit II (MACS Miltenyi Biotec, Germany), and activated by incubation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 mouse T-activator Dynabeads (Invitrogen) and 30 U of recombinant mouse IL-2 (Roche, Germany) for 24 h. Prior to transduction, Dynabeads were magnetically removed from activated CD8+ or CD4+ T cells, and cells were transferred into a 24-well plate coated with Retronectin at 15 μg/mL (Takara, Japan). In each well, 106 T cells in 1 mL of T-cell media were mixed with 1 mL sterile viral supernatant and 60U of recombinant murine IL-2. Plates were centrifuged at 2,000 rpm at 30 °C for 1 h.

Statistical analyses

GraphPad Prism software was used for all statistical analyses. Percent specific lysis was analyzed by t-test and comparison of survival curves by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test. Tumor volume measurements were compared using a one-way analysis of variance followed by comparisons of individual treatments using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Transduced CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were compared with their respective mock transductants. For tumor volume at 26 days, a planned comparison of wild-type 2C CD4+ and m33 CD4+ was analyzed by a t-test. Individual p values are given in figure captions.

Results

IFN-γ treatment is required for detectable surface expression of SIY/Kb complexes on B16-SIY melanoma cells

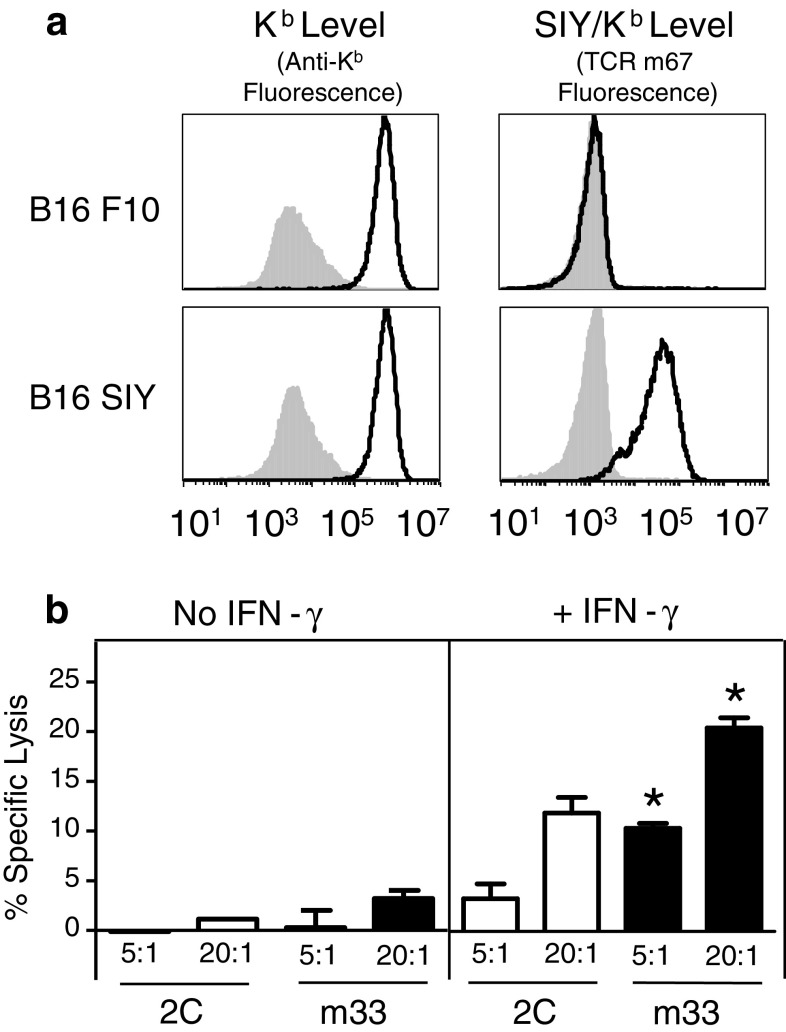

Our recent study showed that the MC57-SIY tumor could be rejected by CD4+ T cells transduced with the high-affinity TCR called m33 [30]. We have shown that this tumor expresses constitutively high levels of SIY/Kb (SIYRYYGL), as measured with a soluble high-affinity TCR called m67 [32]. To explore a tumor system with lower antigen presentation levels, we elected to use the B16 melanoma model, as the SIY-transfected B16 cells did not express SIY/Kb at constitutive levels detectable by the m67 TCR (i.e., B16-SIY expressed less than 1,000 SIY/Kb molecules per cell) (Fig. 1a). To determine whether detectable levels of SIY/Kb could be induced by the treatment with IFN-γ, we cultured B16 F10 (the parental cell line) and B16-SIY cells overnight with 10 ng/mL IFN-γ. Higher surface expression levels of Kb were observed on both cell lines, but induction of SIY/Kb expression was observed only with B16-SIY. These findings demonstrate that although B16-SIY cells have low constitutive levels of SIY/Kb, increased levels can be induced by IFN-γ treatment, as might be achieved in an inflammatory setting in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Following interferon gamma (IFN-γ) treatment, the high-affinity TCR mediates more efficient killing of B16-SIY melanoma cells than the wild-type TCR. a Surface expression of MHC class I Kb and SIY/Kb on B16 F10 parental and B16-SIY melanoma cells, with (black line histograms) and without (shaded histograms) IFN-γ treatment in vitro, as detected with an anti-Kb antibody and the high-affinity single-chain TCR reagent m67. b 2C-transduced and m33-transduced CD4+ T cells can effectively kill IFN-γ pre-treated B16-SIY melanoma cells in vitro. Chromium release was measured from untreated or IFN-γ pre-treated 51Chromium-labeled B16-SIY target cells, which had been incubated with 2C TCR- or m33 TCR-transduced CD4+T cells at 5:1 or 20:1 E:T ratios, in triplicates. *p < 0.01 versus specific lysis of IFN-γ pre-treated B16-SIY with 2C TCR

Lysis of IFN-γ-treated B16-SIY cells by 2C- and m33-transduced CD4+ T cells

Recent evidence suggests that CD4+ T cells can directly kill tumor cells [11, 12]. Accordingly, we evaluated the ability of untreated and IFN-γ-treated B16-SIY cells to be lysed by 2C or m33 TCRs transduced into activated CD4+ polyclonal T cells (Fig. 1b). Untreated B16-SIY melanoma cells were killed poorly by both 2C- and m33-transduced CD4+ T cells, whereas IFN-γ treatment resulted in B16-SIY lysis by both effector cells. Significantly enhanced killing was observed with the high-affinity m33 TCR-transduced T cells at both E/T cell ratios tested. These observations suggest that IFN-γ stimulation at the site of a B16-SIY tumor will be important to raise the surface levels of the SIY/Kb for effective killing. Other studies have shown a critical role for IFN-γ in tumor destruction [33, 34]. These results also show that m33-transduced CD4+ T cells may provide enhanced recognition and activation, probably due to its higher affinity and ability to mediate signaling in a CD8-independent mode.

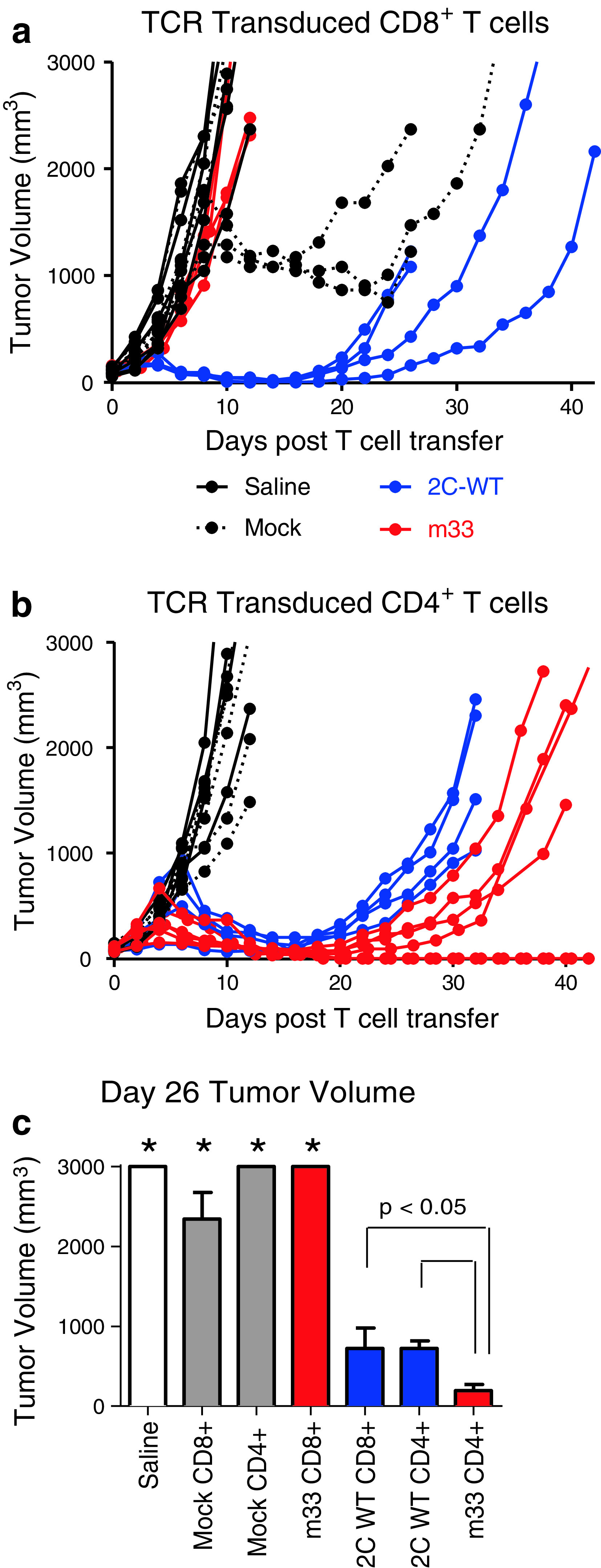

Antigen-specific destruction of B16 melanoma tumors is mediated most effectively by CD4+ T cells transduced with high-affinity m33 TCR

To compare the effectiveness of 2C- and m33-transduced T cells in vivo, we used the B16-SIY cancer cells (1 × 106) as a transplanted, subcutaneous tumor model in Rag1 −/− mice. Five days after tumor transplantation, when the tumors were palpable (~ 100 mm3), adoptive T-cell transfer was performed. Purified primary T cells from C57BL/6 splenocytes were activated ex vivo with anti-CD3-/anti-CD28-coated beads and IL-2. The purified CD8+ or CD4+ T-cell populations were mock transduced, transduced with wild-type affinity 2C TCR (K d = 30 μM) or transduced with the high-affinity m33 TCR (K d = 30 nM). The levels of 2C and m33 TCRs on the transduced populations were similar, as judged by staining with an anti-Vβ8 antibody (data not shown). The efficiency of T-cell transduction in the experiments ranged from 34 to 59 %, as judged by the fraction of T cells positive above the mock-transduced controls.

Mice treated with saline or m33-transduced CD8+ T cells showed uniformly rapid tumor growth (Fig. 2a) likely due to the disappearance of m33 CD8+ T cells [30]. After several days of rapid growth, mock-transduced CD8+ T cells were able to delay tumor growth in several mice. This result was SIY-dependent as the parental line B16 F10 was not controlled by CD8+ T cells (data not shown). These results are consistent with the emergence of some CD8+ T cells in the polyclonal population that recognize SIY/Kb [2, 35]. However, this tumor control was distinctly less effective than 2C-transduced CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2a). The 2C-transduced CD8+ T-cell population mediated rapid reduction in tumor growth but could not prevent relapse.

Fig. 2.

B16-SIY tumor growth delay after treatment with T cells transduced with wild-type affinity 2C TCR or high-affinity m33 TCR. a, b Rag1 −/− mice were implanted with unilateral subcutaneous B16-SIY tumors. Five days later, when tumors were approximately 100 mm3, mice were treated with adoptively transferred CD8+ (a) or CD4+ (b) transduced T cells. Tumors were measured every 2 days after T-cell transfer. Experiments were performed at least twice. Total number of mice for CD8+ T-cell treatments were saline = 6, mock = 6, 2C = 4, m33 = 4. Total number of mice for CD4+ T-cell treatments were saline = 4, mock = 6, 2C = 4, m33 = 6. c Tumor volumes at day 26 post-T-cell transfer were averaged and plotted for each T-cell condition. Tumors treated with CD4+ T cells transduced with m33 were significantly smaller than tumors treated with CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with 2C (*p < 0.05). Tumor volumes from saline, mock CD8+, mock CD4+, and m33 CD8+-treated mice are included as a comparative reference (*)

Mock-transduced CD4+ T cells, unlike mock-transduced CD8+ cells, did not show the same ability to delay growth of B16-SIY tumors (Fig. 2b); this is consistent with the notion that CD8+ T cells, but not CD4+ T cells, express among their native repertoire, TCRs with class I-restricted tumor-antigen specificity. Interestingly, both the 2C- and m33-transduced CD4+ populations were capable of significant tumor control (Fig. 2b), despite 2C TCR’s relatively low affinity. However, m33 CD4+ T cells were more effective at delaying progression of B16-SIY tumors, and two of the mice showed no tumor recurrence even after 60 days. This suggests the importance of TCR affinity in redirected CD4+ effector T cells. To directly compare the adoptive T-cell populations, cohorts were analyzed for average tumor size at a single time point (day 26). This analysis (Fig. 2c) highlighted that high-affinity m33 CD4+ T cells were the most effective at controlling tumor growth.

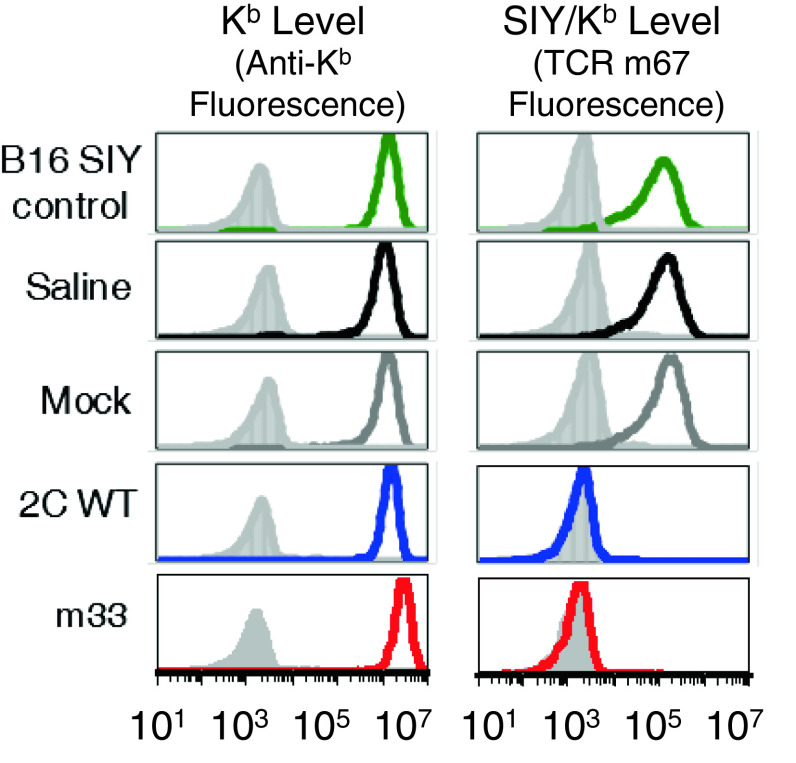

Recurrence of B16-SIY tumors is a result of selection of antigen-loss variants

Despite the tumor destruction and survival benefit observed with TCR-transduced T cells, most of the B16-SIY tumors ultimately escaped immune attack and recurred. To examine why tumor progression eventually occurred, tumors were excised, cultured, and analyzed for antigen-loss variants (ALVs) using the high-affinity TCR m67 as a specific probe. All tumor samples isolated from saline-treated or mock-transduced CD4+ T cell-treated mice expressed uniform levels of Kb and SIY/Kb, similar to that of the cultured B16-SIY cell line (Fig. 3). In contrast, all tumor samples isolated from mice with tumor regression, and then progression, after adoptive cell therapies with 2C WT- or m33-transduced T cells retained high Kb surface expression but lost SIY/Kb expression. Thus, as was often the case in previous studies (e.g., ref [36]), ALVs accounted for the inability to completely eradicate tumors. Interestingly, given the delayed progression of tumors treated with m33 CD4+ populations (and complete eradication in two mice), these T cells appear to have provided enhanced destruction, or delayed growth of ALVs, perhaps through the recognition of cross-presented SIY/Kb on stroma [2].

Fig. 3.

Phenotype of tumors after treatment with transduced T cells. Rag1 −/− mice were implanted with unilateral subcutaneous B16-SIY tumors. Five days later, mice were treated with adoptively transferred CD8+ or CD4+ T cells transduced with wild-type affinity 2C TCR or high-affinity m33 TCR. a Recurring B16-SIY tumors that were initially rejected by 2C WT or m33 T CD4+ T cells were extracted and dissociated, cultured in vitro, and after incubating with IFN-γ (colored histograms) or without IFN-γ (shaded histograms), tumor cells were stained for class I MHC Kb and SIY/Kb. Tumors from mice treated with saline or mock-transduced T cells, which reached criteria for euthanasia within 2 weeks, were also harvested, dissociated, cultured in vitro, and incubated with interferon gamma. All of the tumor cells retained Kb surface expression, but only recurring tumors treated with 2C WT-or m33-transduced CD4+ T cells lost expression of SIY/Kb. Staining is representative of all tumors examined: a total of 25 separate tumors, 16 recurring tumors and 9 primary outgrowth tumors, were analyzed

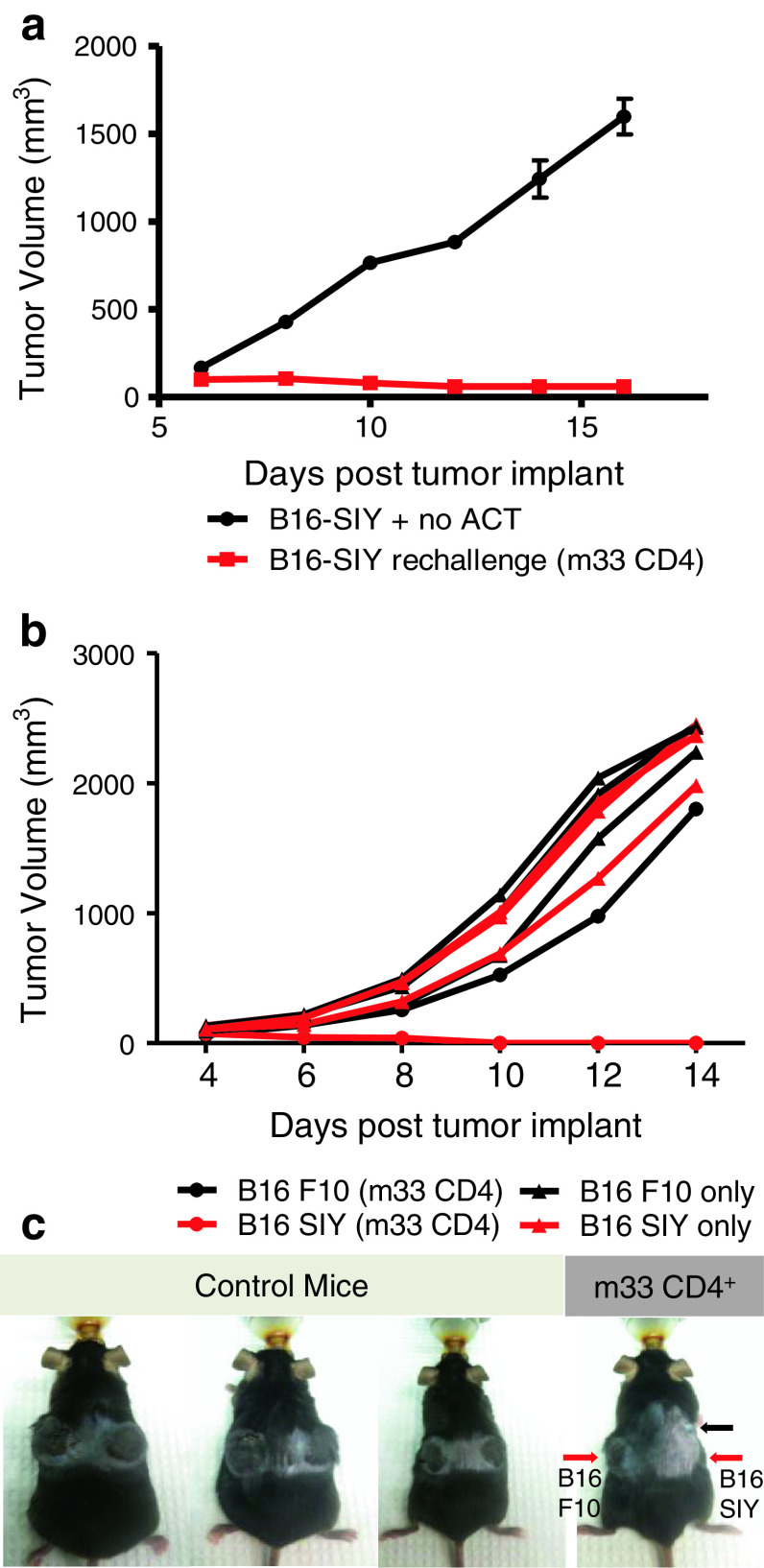

m33 CD4+ T cell-treated long-term survivor mice exhibit persistence of SIY-specific effector memory T cells

Adoptive transfer of m33 CD4+ T cells, but not 2C CD4+ T cells, led to rejection of B16-SIY tumors in some mice. This provided an opportunity to investigate in vivo T-cell persistence and prolonged immune response against B16 melanoma cells. A long-term survivor mouse completely rejected a B16-SIY cancer cell inoculum after a single transfer of m33 CD4+ T cells 65 days earlier (Fig. 4a). Thus, even in the absence of additional T-cell transfer, tumor growth control was maintained over 2 weeks compared to rapidly growing melanoma tumors in untreated control mice. Prevention of tumor outgrowth indicates prolonged anti-tumor activity against B16-SIY cells.

Fig. 4.

Long-term survivor mice demonstrate persistent antigen-specific immune response against B16-SIY tumor re-challenge. a Long-term survivor adoptively transferred with m33 CD4+ T cells 65 days earlier, and control Rag1 −/− mice (n = 3) were implanted with unilateral subcutaneous B16-SIY tumors, and tumor measurements were recorded every 2 days. The tumor volume of mice without previous adoptive T-cell treatment progressively increased, while the long-term survivor completely rejected the B16-SIY challenge. (b, c) Rag1 −/− mice with bilateral subcutaneous B16 F10 parental and B16-SIY tumors were monitored, and tumor measurements recorded every 2 days. The long-term survivor treated with m33 CD4+ T cells 49 days prior to tumor re-challenge showed B16 F10 parental tumor growth while selectively rejecting B16-SIY (b), whereas B16 F10 parental and B16-SIY tumors steadily grew in all mice without previous T-cell therapy. c Images of Rag1 −/− mice 12 days post-subcutaneous tumor implant of B16 F10 on the left flank and B16-SIY on the right flank. Control mice did not receive adoptive T-cell therapy. Both B16 F10 and B16-SIY tumors developed in all mice, except in the long-term survivor mouse previously treated with m33 CD4+ T cells (red arrows at point of B16 F10 and B16-SIY tumor injection). A small relapsing tumor was observed rostral to the tumor cell re-challenge site (black arrow); the origin of this is unclear

To assess whether the immune response against B16-SIY tumor re-challenge was antigen specific, another long-term survivor mouse was bilaterally implanted with B16 F10 and B16-SIY at 49 days post-m33 CD4+ T-cell transfer. This long-term survivor showed uncontrolled B16 F10 tumor growth while selectively rejecting B16-SIY cells. Both B16 F10 and B16-SIY tumors grew rapidly in all untreated control mice (Fig. 4b, c). Lack of an anti-tumor response against the parental line B16 F10 suggests that SIY-specific immunity was generated against B16-SIY melanoma cells.

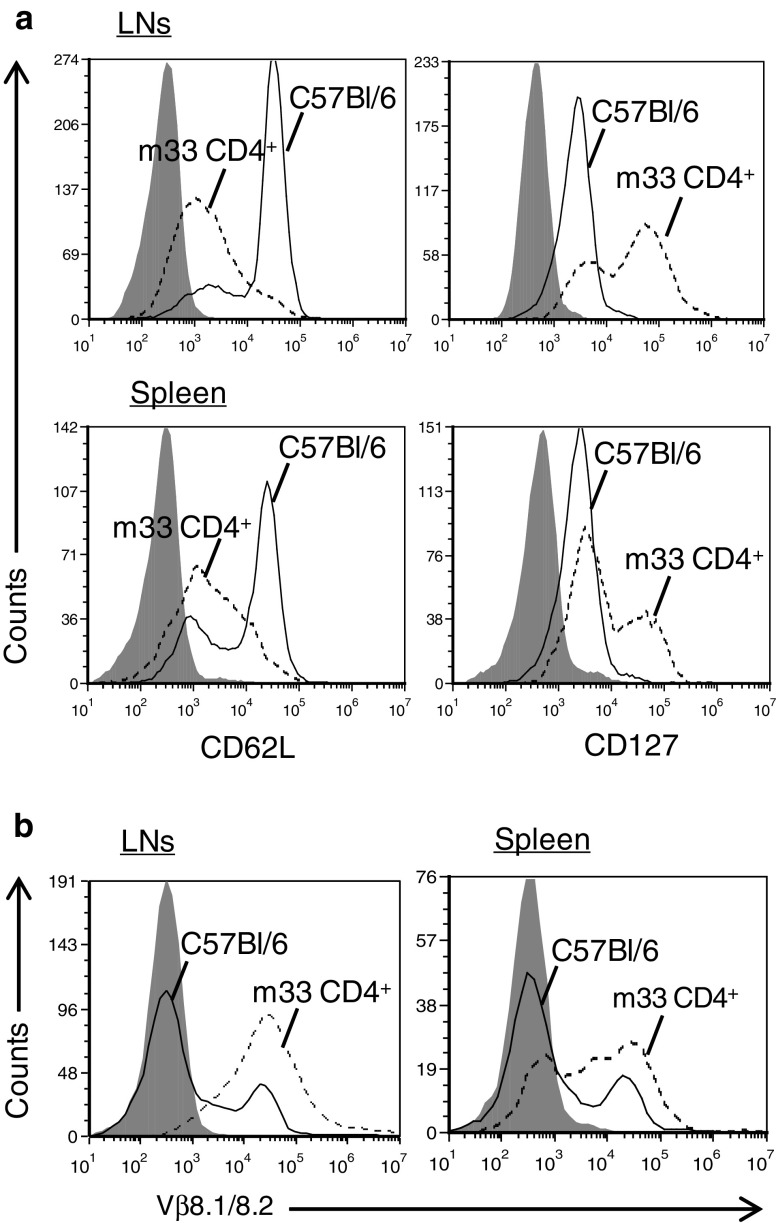

Lymph nodes (LNs) and spleens were harvested from long-term survivor mice for phenotypic characterization of T cells by flow cytometry. Analysis of the lymphoid tissue revealed long-term persistence of CD4+ T cells over 80 days after m33 CD4+ T-cell transfer (Fig. 5a). These CD4+ cells were predominantly CD127high and CD62Llow, a phenotype associated with peripheral effector memory T cells [37–39]. Additionally, we confirmed that the transduced m33 TCR was expressed by Vβ8 staining of the CD4+ cells (Fig. 5b). Thus, persistence of the m33, Vβ8+ effector memory T cells correlated with the results observed following tumor re-challenge. Together, these findings demonstrate that primary CD4+ T cells transduced with high-affinity TCRs can persist in vivo and exert effective anti-tumor protective immunity against B16-SIY melanoma, despite the presence of ALVs among the original tumor population.

Fig. 5.

Adoptive cell therapy with m33 CD4+ T cells leads to long-term persistence of effector memory cells. Phenotypic characterization of lymph nodes (LNs) and spleens harvested from long-term survivor following tumor B16-SIY tumor re-challenge (87 days post-ACT with m33 CD4+ T cells) and C57BL/6 untreated control mice. Flow cytometry profiles are gated on viable, CD4+ cells. a Flow cytometric analysis of CD4+ T cells from LNs (top row) and spleen (bottom row) stained for CD62L and CD127 expression and b T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ8 surface expression. Shadowed histograms represent isotype control staining, solid lines represent C57BL/6 isolated T cells, and dotted lines represent cells isolated from m33 CD4+ T cell-treated long-term survivor

T-cell therapy with CD4+ cells expressing high-affinity m33 TCR lead to enhanced survival of mice with large, established tumors

In our initial studies, tumor-bearing mice were adoptively transferred TCR-transduced T cells 5 days following tumor implant, when tumors measured approximately 100 mm3. We sought to investigate the anti-tumor effectiveness of TCR-transduced cells against more established tumors. Experimental studies with larger and more established tumors provide an improved clinical cancer model in aspects of cellular heterogeneity and tumor vasculature [40, 41]. In this tumor model, cell transfer of T cells was performed 10 days post-tumor implant, when tumors averaged 500 mm3 in size (1 cm in diameter). T-cell therapy with both 2C and m33 CD4+ T-cell populations resulted in enhanced survival despite increased tumor burden at time of T-cell treatment (Fig. 6a). Tumors initially continued to grow for several days after adoptive transfer of T cells. However, within 12 days post-T-cell transfer, tumor size was markedly decreased in both treatment groups compared to mock CD4+-treated mice, which succumb to their tumor within 18 days post-transfer of T cells (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

ACT with CD4+ T cells transduced with high-affinity m33 TCR results in enhanced survival in an established melanoma tumor model. a Survival of Rag1 −/− mice with B16-SIY subcutaneous tumors and ACT with transduced CD4+ T cells 10 days post-tumor implant, when tumors averaged 500 mm3 in size. Saline and mock CD4+-treated mice (solid black and dashed black lines, respectively) reached criteria for euthanasia within 16 days, and 2C WT CD4+-treated mice (blue line) survived up to 32 days post-T-cell transfer (median survival: saline 8 days, mock CD4+ 11 days, 2C WT CD4+ 26 days), while mice treated with high-affinity m33 TCR-transduced T cells (red line) survived significantly longer with a median survival of 36 days (*p < 0.05 compared to all other groups). Total number of mice per experimental group: saline = 5, mock = 2, 2C WT CD4 = 5, and m33 CD4 = 5. b Representative images of B16-SIY subcutaneous tumors 12 and 18 days post-ACT with TCR-transduced CD4+ T cells. c Ex vivo phenotype of TCR-transduced T cell-treated tumors. Melanoma tumors that recur following ACT with 2C WT CD4+ or m33 CD4+ T cells, were stained, following incubation with (colored histograms) or without (shaded histograms) IFN-γ, with anti-Kb and anti-SIY/Kb reagents. Recurring tumors lost SIY antigen expression while retaining class I MHC Kb surface expression

Importantly, again in the model with more established tumors, high-affinity m33 TCR-transduced cells yielded significantly better survival than wild-type 2C TCR-transduced T-cell treatment (Fig. 6a) and even led to a dramatic tumor shrinkage in one mouse from close to criteria for euthanasia with a tumor size of 2,500 mm3 to no measurable mass lasting a period of 6 days. Although tumor size was greatly reduced, all tumors eventually recurred. Ex vivo phenotype of recurring tumors again confirmed that tumor outgrowth was a result of ALVs, which retained the expression of Kb but lost surface expression of SIY/Kb complexes (Fig. 6c).

Discussion

The experimental design described here, with a model tumor antigen (SIY), addresses the question whether there is an optimal affinity for TCRs that can redirect the activities of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against a class I antigen on tumors. Our salient findings are that (1) lower, wild-type affinity TCR within the range found in normal CD8+ T cells (K d of 30 μM) was capable of mediating effective CD8+ T-cell responses in the transduced T-cell system, in-line with many previous studies that used transgenic 2C CD8+ T cells, (2) TCR-transduced CD4+ T cells exhibited both direct killing of the class I-positive tumors in vitro and effective control of tumors in vivo, and (3) an in vitro engineered TCR, m33, with high (nanomolar) affinity mediated more effective tumor targeting by CD4+ T cells than the wild-type 2C TCR.

Compared to results with CD8+ T cells, there was improved tumor-targeting efficacy using CD4+ T cells transduced with the high-affinity TCR. Accordingly, CD4+ cells expressing the m33 TCR (K d of 30 nM) exhibited significant improvements in tumor destruction and longer survival in comparison to wild-type affinity 2C TCR. Impressively, this included treatment of larger, established tumors of up to 2,500 mm3 in one case. By analogy, the second-generation MART-1-specific TCR called DMF5 (K d = 40 μM) was chosen because it exhibited greater activity than the TCR DMF4 in CD4+ T cells in various assays in vitro [22, 27, 42]. The improved efficacy of CD4+ T cells may be associated with the production of cytokines such as IFN-γ, which clearly has a dramatic effect on the expression of the SIY/Kb antigen. These results are in-line with recent observations by Gajewski et al. [43], where IFN-γ-mediated effector function of CD4+ cells was associated with B16 melanoma tumor growth control and reduced tumor vasculature. Earlier studies using the B16-OVA system, and CD8+ OT-1 TCR transgenic T cells, had shown an effect of IFN-γ on host cells, in addition to a direct effect of B16-tumors [44]. Thus, the enhanced effect of CD4+ T cells in our study could also be due to indirect IFN-γ-dependent mechanisms [9–12].

Most previous studies with tumor-reactive T cells have described their TCRs in the context of high or low “avidity”; this is in part because the actual monomeric binding constants (K d values) of TCRs are rarely measured. In the context of many studies with T cells, the term “avidity” has generally referred to the notion that one T cell yielded more effective activity (“higher avidity”) against the same antigen compared to another clone (“lower avidity”). It is useful to consider the 2C system in this context. The 2C TCR showed some activity in CD4+ T cells, and by this criterion, it would be considered “high avidity” in comparison to a SIY-specific TCR that showed no activity in CD4+ T cells. However, 2C TCR is clearly less active in CD4+ T cells than the m33 TCR. Thus, the term high avidity is a relative term, requiring comparison of multiple different TCRs against the same antigenic peptide. We suggest that TCRs derived from typical TILs or ex vivo generated T cells (wild-type TCRs) may not yield the affinities that can mediate more effective activities, as shown here for m33. These affinities may only be achieved by directed evolution in vitro (as with m33) or by other strategies that select for TCRs that bind to class I MHC ligands in the absence of the CD8 co-receptor. Nevertheless, it is clear that driving the affinity too high (e.g., picomolar) may also yield self-peptide reactivities even in the CD4+ T-cell population [18], and thus, there will be an optimal range of affinities.

Tumor-specific CD4+ T cells have been demonstrated to have a direct role in mediating tumor regression. In a clinical study, one patient experienced complete tumor remission following infusion of melanoma antigen-specific CD4+ T cells [45]. The possible limitations to the use of TCR-gene modified CD4+ cells for ACT include the downregulation of MHC-class I levels, and the possible need for CD8 co-receptor to recognize lower levels of antigen. Antigen-loss variants (ALVs) are also a major problem associated with adoptive T-cell therapies that target a single antigen [36]. In particular with melanoma, T-cell therapy exerts a strong selective pressure on tumor cells resulting in the emergence of ALVs in experimental mice as well as clinically [46, 47]. To some extent at least, higher affinity TCRs may mitigate each of these issues. However, it remains to be seen whether the affinity of TCRs against class I MHC that drive particular CD4+ T-cell subsets (TH1, TH2, TH17, Treg or memory versus effector) will differ. These studies can now be approached with 2C, m33, and our collection of affinity variants of these TCRs [20].

It is worth considering why some previous studies have described the complete elimination of tumors, including ALVs, in mice that received TCR transgenic T cells, as opposed to TCR-transduced T cells. In the most directly related study with the 2C system, it was shown that large, established MC57-SIY-hi tumors could be completely eliminated by transfer of 2C TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells [48]. However, MC57-SIY-lo tumors could not be completely eliminated, due to ALVs and reduced levels of stroma cross-presentation [32, 48, 49]. Other studies, with MC57-gp33-hi and MC57-gp33-lo tumors found similar results using P14 TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells [50]. Thus, antigen levels clearly are one factor in determining whether ALVs can be destroyed, and in this respect, the B16-SIY tumors express no detectable levels of SIY/Kb unless they are induced with IFN-γ. In contrast, the MC57 tumors constitutively express detectable levels the SIY/Kb antigen [32].

In addition to antigen levels, there are other factors that could contribute to the outgrowth of ALVs as observed in previous reports and in the present study. There is considerable variability in the number of tumor cells used in the different studies and the timing of adoptive T-cell transfers, even in the B16 melanoma models. Other studies have injected 5 × 104 or 105 B16 tumor cells [44, 47, 50], whereas the mice in our study received 106 B16-SIY tumor cells. Other studies transferred T cells 1–7 days following tumor injection [44, 47, 50], while our study injected T cells either 5 or 10 days after B16-SIY injection. Given the rapid growth rate of B16 tumors, clearly, the size of the tumor at time of T-cell treatment will be related to the likelihood of ALV outgrowth.

Finally, the T-cell population(s) used for treatment will also impact the ability to control tumor growth and ALV destruction. A previous study showed that a B16-gp33 tumor was effectively controlled, without ALVs, by P14 TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells, but not by P14 TCR-transduced T cells [50]. These effects could be related to slightly lower transduced TCR levels (compared to transgenic T cells), due to mispairing with endogenous TCR chains [51]. Higher affinity TCRs require fewer molecules per T cell in order to mediate activity, and they can do so at lower antigen levels [52], which could in part explain why m33 exhibits improved activity compared to 2C. It should also be noted that in our studies, the recipient T cells are polyclonal CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from C57Bl/6 mice, not activated TCR transgenic T cells (e.g., OT-1) [30, 50]. Furthermore, recipient T cells in our study have undergone in vitro activation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 antibody-coated beads, whereas most transgenic T cells studies used T cells activated with the cognate peptide [44, 47, 50]. It is unclear whether different methods of activation lead to different levels of function (e.g., cytokine release, persistence, activation-induced cell death) that might impact efficacy. Polyclonal T cells may also contain subpopulations of regulatory cells [53] that contribute ultimately to effects on tumor control.

In summary, there are many complex factors that need to be examined to fully understand what optimal T-cell format will be for clinical adoptive T-cell therapies. We provide evidence that CD4+ T-cell therapy with high-affinity TCR resulted in tumor rejection; in some cases, the rejection resulted in long-term survivor mice exhibiting SIY-specific tumor responses against B16-SIY tumor re-challenge. We also observed CD62Llow and CD127high TCR-transduced effector memory T cells. In a well-established tumor model with tumors measuring on average 1 cm in diameter, m33-expressing CD4+ cells displayed strong anti-tumor effects. Adoptive transfer of m33 CD4+ cells in this model displayed significant tumor destruction and improved survival compared to 2C CD4+ treatment. High-affinity TCR-transduced CD4+ cells not only provide antigen-specific effective immune responses in vivo but they also persist long-term after tumor regression. Together, these findings provide evidence of the advantages of using TCRs with high affinity, especially the possibility of redirecting both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells to target the same MHC-class I-restricted tumor antigens. This is especially interesting in the light of the need for having both CD8 and CD4 antigens on the same cell [2].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tom Gajewski for generously providing the B16-SIY murine melanoma cell line. We also thank Melanie Studzinski, Sydney Sherman, and Natalia Wolosowicz for experimental support. This work was supported by a grant from the Melanoma Research Alliance (to D. M. K.), by NIH grant CA097296 (to D. M. K. and H. S.), and funds from an anonymous donor (to EJR). BE was supported by a Research Fellowship of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft; J. D. S. was supported by the Samuel and Ruth Engelberg/Irvington Institute Fellowship of the Cancer Research Institute.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Carolina M. Soto, Jennifer D. Stone and Adam S. Chervin contributed equally.

References

- 1.Morris EC, Tsallios A, Bendle GM, Xue SA, Stauss HJ. A critical role of T cell antigen receptor-transduced MHC class I-restricted helper T cells in tumor protection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(22):7934–7939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500357102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schietinger A, Philip M, Liu RB, Schreiber K, Schreiber H. Bystander killing of cancer requires the cooperation of CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells during the effector phase. J Exp Med. 2010;207(11):2469–2477. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bos R, Sherman LA. CD4+ T-cell help in the tumor milieu is required for recruitment and cytolytic function of CD8+ T lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70(21):8368–8377. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188(12):2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surman DR, Dudley ME, Overwijk WW, Restifo NP. Cutting edge: CD4+ T cell control of CD8+ T cell reactivity to a model tumor antigen. J Immunol. 2000;164(2):562–565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antony PA, Piccirillo CA, Akpinarli A, Finkelstein SE, Speiss PJ, Surman DR, Palmer DC, Chan CC, Klebanoff CA, Overwijk WW, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. CD8+ T cell immunity against a tumor/self-antigen is augmented by CD4+ T helper cells and hindered by naturally occurring T regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2591–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novy P, Quigley M, Huang X, Yang Y. CD4 T cells are required for CD8 T cell survival during both primary and memory recall responses. J Immunol. 2007;179(12):8243–8251. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang LX, Shu S, Disis ML, Plautz GE. Adoptive transfer of tumor-primed, in vitro-activated, CD4+ T effector cells (TEs) combined with CD8+ TEs provides intratumoral TE proliferation and synergistic antitumor response. Blood. 2007;109(11):4865–4876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-045245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin Z, Blankenstein T. CD4+ T cell–mediated tumor rejection involves inhibition of angiogenesis that is dependent on IFN gamma receptor expression by nonhematopoietic cells. Immunity. 2000;12(6):677–686. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen PA, Peng L, Plautz GE, Kim JA, Weng DE, Shu S. CD4+ T cells in adoptive immunotherapy and the indirect mechanism of tumor rejection. Crit Rev Immunol. 2000;20(1):17–56. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.v20.i1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quezada SA, Simpson TR, Peggs KS, Merghoub T, Vider J, Fan X, Blasberg R, Yagita H, Muranski P, Antony PA, Restifo NP, Allison JP. Tumor-reactive CD4(+) T cells develop cytotoxic activity and eradicate large established melanoma after transfer into lymphopenic hosts. J Exp Med. 2010;207(3):637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Y, Akpinarli A, Maris C, Hipkiss EL, Lane M, Kwon EK, Muranski P, Restifo NP, Antony PA. Naive tumor-specific CD4(+) T cells differentiated in vivo eradicate established melanoma. J Exp Med. 2010;207(3):651–667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuertes MB, Kacha AK, Kline J, Woo SR, Kranz DM, Murphy KM, Gajewski TF. Host type I IFN signals are required for antitumor CD8+ T cell responses through CD8{alpha}+ dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(10):2005–2016. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harlin H, Meng Y, Peterson AC, Zha Y, Tretiakova M, Slingluff C, McKee M, Gajewski TF. Chemokine expression in melanoma metastases associated with CD8+ T-cell recruitment. Cancer Res. 2009;69(7):3077–3085. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holler PD, Holman PO, Shusta EV, O’Herrin S, Wittrup KD, Kranz DM. In vitro evolution of a T cell receptor with high affinity for peptide/MHC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(10):5387–5392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080078297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holler PD, Kranz DM. Quantitative analysis of the contribution of TCR/pepMHC affinity and CD8 to T cell activation. Immunity. 2003;18:255–264. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Moysey R, Molloy PE, Vuidepot AL, Mahon T, Baston E, Dunn S, Liddy N, Jacob J, Jakobsen BK, Boulter JM. Directed evolution of human T-cell receptors with picomolar affinities by phage display. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(3):349–354. doi: 10.1038/nbt1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Bennett AD, Zheng Z, Wang QJ, Robbins PF, Yu LY, Li Y, Molloy PE, Dunn SM, Jakobsen BK, Rosenberg SA, Morgan RA. High-affinity TCRs generated by phage display provide CD4+ T cells with the ability to recognize and kill tumor cell lines. J Immunol. 2007;179(9):5845–5854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.9.5845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robbins PF, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Zhao Y, Wargo JA, Zheng Z, Xu H, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Johnson LA, Bennett AD, Dunn SM, Mahon TM, Jakobsen BK, Rosenberg SA. Single and dual amino acid substitutions in TCR CDRs can enhance antigen-specific T cell functions. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6116–6131. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chervin AS, Stone JD, Holler PD, Bai A, Chen J, Eisen HN, Kranz DM. The impact of TCR-binding properties and antigen presentation format on T cell responsiveness. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):1166–1178. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Hughes MS, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Royal RE, Topalian SL, Kammula US, Restifo NP, Zheng Z, Nahvi A, de Vries CR, Rogers-Freezer LJ, Mavroukakis SA, Rosenberg SA. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314(5796):126–129. doi: 10.1126/science.1129003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson LA, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Cassard L, Yang JC, Hughes MS, Kammula US, Royal RE, Sherry RM, Wunderlich JR, Lee CC, Restifo NP, Schwarz SL, Cogdill AP, Bishop RJ, Kim H, Brewer CC, Rudy SF, VanWaes C, Davis JL, Mathur A, Ripley RT, Nathan DA, Laurencot CM, Rosenberg SA. Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood. 2009;114(3):535–546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gattinoni L, Powell DJ, Jr, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive immunotherapy for cancer: building on success. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(5):383–393. doi: 10.1038/nri1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammertoens T, Blankenstein T. Making and circumventing tolerance to cancer. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(9):2345–2353. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitt TM, Ragnarsson GB, Greenberg PD. T cell receptor gene therapy for cancer. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20(11):1240–1248. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Nahvi AV, Helman LJ, Mackall CL, Kammula US, Hughes MS, Restifo NP, Raffeld M, Lee CC, Levy CL, Li YF, El-Gamil M, Schwarz SL, Laurencot C, Rosenberg SA. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY-ESO-1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(7):917–924. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson LA, Heemskerk B, Powell DJ, Jr, Cohen CJ, Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA. Gene transfer of tumor-reactive TCR confers both high avidity and tumor reactivity to nonreactive peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2006;177(9):6548–6559. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borbulevych OY, Santhanagopolan SM, Hossain M, Baker BM. TCRs used in cancer gene therapy cross-react with MART-1/Melan-A tumor antigens via distinct mechanisms. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2453–2463. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corse E, Gottschalk RA, Krogsgaard M, Allison JP. Attenuated T cell responses to a high-potency ligand in vivo. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(9):1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engels B, Chervin AS, Sant AJ, Kranz DM, Schreiber H. Long-term persistence of CD4(+) but rapid disappearance of CD8(+) T cells expressing an MHC class I-restricted TCR of nanomolar affinity. Mol Ther. 2012;20(3):652–660. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holler PD, Chlewicki LK, Kranz DM. TCRs with high affinity for foreign pMHC show self-reactivity. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(1):55–62. doi: 10.1038/ni863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang B, Bowerman NA, Salama JK, Schmidt H, Spiotto MT, Schietinger A, Yu P, Fu YX, Weichselbaum RR, Rowley DA, Kranz DM, Schreiber H. Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(1):49–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumberg D, Monach PA, Wanderling S, Philip M, Toledano AY, Schreiber RD, Schreiber H. CD4(+) T cells eliminate MHC class II-negative cancer cells in vivo by indirect effects of IFN-gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(15):8633–8638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang B, Karrison T, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. IFN-gamma- and TNF-dependent bystander eradication of antigen-loss variants in established mouse cancers. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(4):1398–1404. doi: 10.1172/JCI33522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DuPage M, Cheung AF, Mazumdar C, Winslow MM, Bronson R, Schmidt LM, Crowley D, Chen J, Jacks T. Endogenous T cell responses to antigens expressed in lung adenocarcinomas delay malignant tumor progression. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):72–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Witte MA, Jorritsma A, Kaiser A, van den Boom MD, Dokter M, Bendle GM, Haanen JB, Schumacher TN. Requirements for effective antitumor responses of TCR transduced T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181(7):5128–5136. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.5128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huster KM, Busch V, Schiemann M, Linkemann K, Kerksiek KM, Wagner H, Busch DH. Selective expression of IL-7 receptor on memory T cells identifies early CD40L-dependent generation of distinct CD8+ memory T cell subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(15):5610–5615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308054101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powell DJ, Jr, Dudley ME, Robbins PF, Rosenberg SA. Transition of late-stage effector T cells to CD27+ CD28+ tumor-reactive effector memory T cells in humans after adoptive cell transfer therapy. Blood. 2005;105(1):241–250. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bachmann MF, Wolint P, Schwarz K, Jager P, Oxenius A. Functional properties and lineage relationship of CD8+ T cell subsets identified by expression of IL-7 receptor alpha and CD62L. J Immunol. 2005;175(7):4686–4696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wen FT, Thisted RA, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. A systematic analysis of experimental immunotherapies on tumors differing in size and duration of growth. OncoImmunology. 2012;1(2):172–178. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.2.18311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Finkelstein SE, Heimann DM, Klebanoff CA, Antony PA, Gattinoni L, Hinrichs CS, Hwang LN, Palmer DC, Spiess PJ, Surman DR, Wrzesiniski C, Yu Z, Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Bedside to bench and back again: how animal models are guiding the development of new immunotherapies for cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76(2):333–337. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0304120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borbulevych OY, Insaidoo FK, Baxter TK, Powell DJ, Jr, Johnson LA, Restifo NP, Baker BM. Structures of MART-126/27-35 Peptide/HLA-A2 complexes reveal a remarkable disconnect between antigen structural homology and T cell recognition. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(5):1123–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kline J, Zhang L, Battaglia L, Cohen KS, Gajewski TF. Cellular and molecular requirements for rejection of B16 melanoma in the setting of regulatory T cell depletion and homeostatic proliferation. J Immunol. 2012;188(6):2630–2642. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuler T, Blankenstein T. Cutting edge: CD8+ effector T cells reject tumors by direct antigen recognition but indirect action on host cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(9):4427–4431. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hunder NN, Wallen H, Cao J, Hendricks DW, Reilly JZ, Rodmyre R, Jungbluth A, Gnjatic S, Thompson JA, Yee C. Treatment of metastatic melanoma with autologous CD4+ T cells against NY-ESO-1. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(25):2698–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, Sherry RM, Topalian SL, Restifo NP, Royal RE, Kammula U, White DE, Mavroukakis SA, Rogers LJ, Gracia GJ, Jones SA, Mangiameli DP, Pelletier MM, Gea-Banacloche J, Robinson MR, Berman DM, Filie AC, Abati A, Rosenberg SA. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346–2357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaluza KM, Thompson JM, Kottke TJ, Flynn Gilmer HC, Knutson DL, Vile RG. Adoptive T cell therapy promotes the emergence of genomically altered tumor escape variants. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(4):844–854. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spiotto MT, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Bystander elimination of antigen loss variants in established tumors. Nat Med. 2004;10(3):294–298. doi: 10.1038/nm999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang B, Zhang Y, Bowerman NA, Schietinger A, Fu YX, Kranz DM, Rowley DA, Schreiber H. Equilibrium between host and cancer caused by effector T cells killing tumor stroma. Cancer Res. 2008;68(5):1563–1571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinhold M, Sommermeyer D, Uckert W, Blankenstein T. Dual T cell receptor expressing CD8+ T cells with tumor- and self-specificity can inhibit tumor growth without causing severe autoimmunity. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5534–5542. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bendle GM, Linnemann C, Hooijkaas AI, Bies L, de Witte MA, Jorritsma A, Kaiser AD, Pouw N, Debets R, Kieback E, Uckert W, Song JY, Haanen JB, Schumacher TN. Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat Med. 2010;16(5):565–570. doi: 10.1038/nm.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schodin BA, Tsomides TJ, Kranz DM. Correlation between the number of T cell receptors required for T cell activation and TCR-ligand affinity. Immunity. 1996;5:137–146. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80490-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brusko TM, Koya RC, Zhu S, Lee MR, Putnam AL, McClymont SA, Nishimura MI, Han S, Chang LJ, Atkinson MA, Ribas A, Bluestone JA. Human antigen-specific regulatory T cells generated by T cell receptor gene transfer. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spiotto MT, Yu P, Rowley DA, Nishimura MI, Meredith SC, Gajewski TF, Fu YX, Schreiber H. Increasing tumor antigen expression overcomes “ignorance” to solid tumors via crosspresentation by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Immunity. 2002;17(6):737–747. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blank C, Brown I, Peterson AC, Spiotto M, Iwai Y, Honjo T, Gajewski TF. PD-L1/B7H-1 inhibits the effector phase of tumor rejection by T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(3):1140–1145. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]