Abstract

Experiences with perceived discrimination (e.g., perceptions of being treated unfairly due to race or ethnicity) are expected to impact negatively youths’ prosocial development. However, resilience often occurs in light of such experiences through cultural factors. The current longitudinal study examined the influence of perceived discrimination on the emergence of Mexican American adolescents’ later prosocial tendencies, and examined the mediating role of Mexican American values (e.g., familism, respect, and religiosity). Participants included 749 adolescents (49 % female) interviewed at 5th, 7th, and 10th grade. Results of the current study suggested that, although perceived discrimination was associated negatively with some types of prosocial tendencies (e.g., compliant, emotional, and dire) and related positively to public prosocial helping, the associations were mediated by youths’ Mexican American values. Directions for future research are presented and practical implications for promoting adolescents’ resilience are discussed.

Keywords: Adolescents, Discrimination, Prosocial tendencies, Mexican American values

A Brief Overview of the Associations Between Perceived Discrimination, Cultural Values, and Mexican American Youths’ Prosocial Tendencies

Developmental increases in cognitive awareness about the self may lead adolescents to be relatively more sensitive to the evaluations of others (e.g., Rankin et al. 2004; Sebastian et al. 2008). Hence, negative social experiences related to ethnicity, such as perceived discrimination (e.g., perceptions of differential treatment based on one’s race or ethnicity), may challenge developmental tasks that are critical for adolescents, such as the development of prosocial tendencies (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and behaviors oriented towards the benefit of others). Indeed, existing work has demonstrated that perceived discrimination has negative effects on other aspects of healthy development (e.g., Pascoe and Richman 2009; Romero and Roberts 2003; Umaña-Taylor and Updegraff 2007). However, some studies have found that discrimination does not always result in negative outcomes for Mexican American adolescents (e.g., Berkel et al. 2010; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2012). In some cases, experiencing discrimination may prompt Mexican American youth to further explore their cultural heritage (Tajfel and Turner 1986), an individual characteristic that is linked to better psychological adjustment (e.g., Berkel et al. 2010; Delgado et al. 2011). It is, therefore, important to understand the processes involved in developmental competencies (rather than deficits) to understand how resilience transpires (García Coll et al. 1996). Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine the direct associations between perceived discrimination and one particular area of developmental competence, prosocial tendencies, as well as the potential role of ethnically related cultural values as a mediator in these associations.

Prosocial Development and Mexican American Youth

Prosocial behaviors, defined as behaviors that are intended to benefit others, are an important aspect of adolescents’ positive development (Eisenberg et al. 1991; Carlo and Randall 2002). Normative developmental transitions (e.g., increased cognitive abilities, biological changes, and increases in roles and social expectations) in adolescence present new opportunities for prosocial behaviors to be further expressed (Carlo et al. 1999). For example, adolescents may engage in a number of prosocial behaviors ranging from compliant forms, such as helping teachers in the classroom, to public forms, such as volunteering in their communities (Carlo and Randall 2002; Sherrod and Lauckhardt 2009). Previous research suggests that endorsement of prosocial behaviors increases from childhood to adolescence and from adolescence into adulthood (Eisenberg et al. 2005, 2009). Furthermore, adolescents spend more time out of the home in other social contexts, such as in schools and out-of-school time activities, which enable them to practice behaviors intended to help others outside of the family unit (e.g., neighbors). On the other hand, adolescents also are more likely to encounter ethnic discrimination in social contexts outside of the home (Greene et al. 2006), and in turn, perceived discrimination may pose a threat to adolescents’ prosocial development.

Previous studies have found that distinct types of prosocial tendencies may exist. For example, factor analytic work by Carlo and colleagues (e.g., Carlo et al. 2010; Carlo and Randall 2002) found six types of prosocial tendencies: compliant (i.e., intentions to help when asked), anonymous (i.e., willingness to help without others knowing), dire (i.e., intentions to assist in emergency situations), emotional (i.e., helping in emotionally charged situations), altruistic (i.e., intentions to help with no expectation of reward), and public (i.e., intentions to help when others are watching). Previous work assessing the different types of prosocial tendencies has indicated that they may be related differentially to each other, and that each type of helping may be induced by different motivations (for a full review, see Carlo and Randall 2002). For example, altruistic helping, defined as helping motivated by concern for others’ needs, initiated by empathy and the ability to take another person’s perspective (Eisenberg et al. 1991), is different from the motivation underlying public helping, inspired by expectations of recognition or reward. Similarly, compliant helping, or helping in response to a verbal request, may be related to temperament (e.g., lack of assertiveness; Eisenberg et al. 1991; Eisenberg and Fabes 1998), while emotional helping is associated with awareness of others’ needs in emotionally charged situations (Carlo and Randall 2002). Given the distinctiveness of types of prosocial behaviors, the current study examined the impact of perceived discrimination on the six types described above.

Of particular relevance to Mexican American adolescents, cultural factors are related specifically to the development of prosocial tendencies (e.g., Armenta et al. 2011). Cultural socialization is the process through which families instill cultural pride in their youth through activities, such as participation in cultural events and teaching youth about their groups’ heritage and cultural practices (Hughes 2003; Rodriguez et al. 2009), and studies show that cultural socialization and the maintenance of heritage culture is a common practice for many Mexican American families (Bernal et al. 1993; Halgunseth et al. 2006; Umaña-Taylor and Fine 2004). Among Mexican American youth, scholars have shown that connection to their country of origin is associated with positive developmental outcomes, including fewer internalizing and externalizing behaviors and increased prosocial tendencies (e.g., Armenta et al. 2011; Calderón-Tena et al. 2011; Gonzales et al. 2008).

Early work by Knight et al. (1993) found that Mexican American parents’ cultural socialization was related to more cooperative behaviors in Mexican American children. Calderón-Tena et al. (2011) found that family cultural orientations (familism values) were related positively to prosocial tendencies among Mexican American adolescents. Moreover, a study by Schwartz et al. (2007) found that orientation towards Hispanic/Latino culture (e.g., listening to Spanish music and associating mostly with Hispanic/Latino people) was related positively to Latino early adolescents’ prosocial behaviors. Finally, Armenta et al. (2011) found that Mexican American youths’ familism values were associated positively with their compliant, emotional, dire, and anonymous helping, but was not related to altruism or public helping.

Prosocial development is an important dimension of Mexican American youths’ positive normative development that has received increasing attention recently (e.g., Calderón-Tena et al. 2011; Carlo et al. 2011; Knight and Carlo 2012), as scholars have called for more research on positive developmental processes associated with ethnicity (e.g., García Coll et al. 1996; Quintana et al. 2006). Perceived discrimination, unfortunately, is another common feature of the life experiences of Mexican American youth and this negative experience may pose a threat to this aspect of positive development.

Discrimination and its Impact on Prosocial Development

Perceived discrimination has been defined as the “subjective experience of being treated unfairly relative to others in everyday experiences” (Flores et al. 2008, p. 402), and is a type of social stress experienced commonly by ethnic minorities. Previous studies have found that the probability of experiencing discrimination increases in adolescence as ethnic minority youth spend more time in social contexts outside of the home (e.g., Fisher et al. 2000; Sellers et al. 2006). For these reasons, scholars have called for more studies that examine the effects of discrimination on psychosocial adjustment among adolescents in particular (e.g., Edwards and Romero 2008; Williams et al. 2008). While several studies have found that perceived discrimination is related negatively to other aspects of positive development among Mexican American adolescents, such as lower self-esteem and academic achievement (e.g., Berkel et al. 2010; Delgado et al. 2011; Umaña-Taylor and Updegraff 2007), no studies to date have examined the impact of perceived discrimination on adolescents’ prosocial tendencies. However, there are theoretical reasons and related empirical evidence to suggest that perceived discrimination may influence prosocial tendencies, and that this influence may vary for different types of prosocial tendencies.

Perceived discrimination can be considered a type of social exclusion (Major and O’Brien 2005). Richman and Leary (2009) have argued that social exclusion fosters feelings of rejection and that individuals may react to feelings of rejection in many ways, including increased need for social connection, engaging in antisocial behaviors to protect one’s sense of self, or withdrawing from social situations to avoid further rejection. Furthermore, experimental studies have found that feelings associated with social exclusion are linked negatively to helping behaviors (e.g., DeWall and Baumeister 2006). For example, studies have shown that the threat of being alone is associated with less empathy (De-Wall and Baumeister 2006) and fewer instances of helping behaviors, such as helping an experimenter pick up a pencil or collaborating with a fellow student (Twenge et al. 2007). For these reasons, perceived discrimination, as a type of social exclusion, may be associated negatively with types of prosocial tendencies (such as altruistic, emotional, and dire helping) that are induced by empathy or perspective taking. Similarly, adolescents may be less likely to engage in prosocial tendencies that require approval seeking if they perceive the social context to be discriminatory against them. On the other hand, further research suggests that when people feel that they are being treated unfairly due to group membership (e.g., race, ethnicity, and gender) they may be more inclined to help in ways that help their ethnic group, such as through engagement in social justice activities, or actions that make the group look more favorable in society (O’Leary and Romero 2011; Richman and Leary 2009). Thus, experiencing perceived discrimination may be related positively to adolescents’ public helping. While the aforementioned studies provide some theoretical evidence for how perceived discrimination may relate to prosocial tendencies, to our knowledge this is the first study to test these hypotheses in a longitudinal study of adolescents with six types of prosocial tendencies.

Mexican American Values as a Mediator

A number of researchers (e.g., Berkel et al. 2010; Gonzales et al. 2008) have suggested that the internalization of Mexican American values may serve a protective function to reduce the impact of minority status risk factors, such as perceived discrimination, on a variety of development outcomes. In these cases, cultural variables mediated the relationship between stressors and adolescent adjustment operating as risk reducers by dampening the negative effects of stressors (Roosa et al. 1997). In addition, cultural mediators also may contribute to compensating positive effects that can help mitigate the negative effect of risk factors on healthy development. For example, Berkel et al. (2010) found that although perceived discrimination had negative effects on internalizing symptoms, externalizing behaviors, and academic outcomes, it also fostered the internalization of Mexican American values which in turn had a compensatory (i.e., positive) effect on these outcomes.

Mexican American values, marked by notions of familism, respect for elders, and religiosity, are particularly important to Mexican American families (Knight et al. 1993), and have been identified as a cultural resource that promotes resilience in Mexican American youth (e.g., Gonzales et al. 2008). Studies have found repeatedly that teaching youth about cultural traditions and heritage is an important practice among Mexican origin families (e.g., Bernal et al. 1993; Halgunseth et al. 2006; Umaña-Taylor and Fine 2004), and that connection to cultural heritage is linked to better developmental outcomes for Mexican American youth. The literature also indicates that Mexican American values share important associations with youths’ prosocial development (e.g., Knight and Carlo 2012). For example, the adherence to traditional Mexican American values (e.g., familism, respect for parents and elders) embeds youth in prosocial communities that foster behaviors that are socially acceptable. Previous studies have found that these values are related positively to youths’ prosocial tendencies (e.g., Calderón-Tena et al. 2011; Carlo et al. 2011; Knight and Carlo 2012). Indeed, Knight and Carlo (2012) have suggested that the internalization of Mexican American values may foster a dispositional orientation to be prosocial among youth.

Current Study

In the current study, we expected that higher perceived discrimination would be associated with fewer instances of most types of prosocial tendencies among Mexican American adolescents, especially prosocial tendencies (e.g., altruistic, emotional, and dire) that are motivated by empathy and perspective taking. However, we expected that perceived discrimination would be associated with higher instances of helping that may be motivated by intentions to help one’s ethnic group (e.g., public). We also expected that higher perceived discrimination would be associated with higher levels of Mexican American values, which in turn, would be associated with higher levels of prosocial tendencies. Hence, we hypothesized that the relationship between perceived discrimination and prosocial tendencies would be at least partially mediated by Mexican American values.

In addition, prior research suggests that Mexican American males and females differ in both their experiences with perceived discrimination (Pérez et al. 2008; Umaña-Taylor and Updegraff 2007) and the expression of various prosocial tendencies (Fabes et al. 1999; McGinley et al. 2010). Furthermore, previous studies have found that the strength of Mexican American values varies by youths’ nativity (e.g., Gonzales et al. 2008). Therefore, we tested whether or not gender and youths’ country of origin (US-born and Mexicoborn) moderated the relationships of adolescents’ perceived discrimination, prosocial tendencies, and Mexican American values. Although previous research has found mean level differences by gender and nativity among the variables of interest in the current study, we did not expect the overall processes (i.e., the associations among these variables) to differ across gender and nativity.

Method

Participants

Data for the current study were derived from the first three waves (Time 1–3; 5th, 7th, and 10th grade) of an ongoing longitudinal study investigating the role of culture and context in the lives of Mexican American families (Roosa et al. 2008). Participants were 749 Mexican American adolescents who were selected from rosters of schools that served ethnically and linguistically diverse communities in a large southwestern metropolitan area. In total, Mexican American families from 47 schools in 18 public school districts, the Catholic Diocese, and alternative schools in the Southwest region of the United States participated. Eligible families met the following criteria: (a) they had a fifth grader attending a sampled school; (b) both mother and child agreed to participate; (c) the mother was the child’s biological mother, lived with the child, and self-identified as Mexican or Mexican American; (d) the child’s biological father was also reported to be of Mexican origin; (e) the child was not severely learning disabled; and (e) no step-father or mother’s boyfriend was living with the child (unless the boyfriend was the biological father of the target child). Family incomes at Time 1 ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $95,000, with the average family reporting an income of $30,000–$35,000. In terms of language, 30.2 % of mothers, 23.2 % of fathers, and 82.5 % of adolescents were interviewed in English. The mean age of youth (49 % female) at T1 was 10.4, and the majority of adolescents were born in the US (70 %).

Procedure

Youth participated in in-home Computer Assisted Personal Interviews, scheduled at the family’s convenience. Interviews were about 2.5 h long. Each interviewer received at least 40 h of training, which included information on the project’s goals, characteristics of the target population, professional conduct, and the critical role they would play in collecting the data. Interviewers read each survey question and possible response aloud in participants’ preferred language to reduce problems related to variations in literacy levels. Youth were compensated for their time at all three waves of data collection.

Measures

Perceived Discrimination

Perceived discrimination was measured as a mean composite of nine items designed to assess discrimination experiences from peers and teachers, and items reflected both personal experiences of discrimination and public regard. Because no measure of discrimination for Mexican Americans was available at the time of this study’s development, items were adapted from two measures that had been validated for other groups (i.e., Racism in the Workplace Scale; Hughes and Dodge 1997; Schedule of Racist Events; Landrine and Klonoff 1996). Sample items included, “How often have kids at school called you names because you are Mexican American?” and “How often have you had to work harder in school than White kids to get the same praise or the same grades from your teachers because you are Mexican American?” Responses were scored on a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 = not at all true to 5 = very true. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure at Time 1 was .74.

Mexican American Cultural Values

The Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (MACVS; Knight et al. 2010) captures five dimensions of Mexican American cultural values: supportive and emotional familism (six items, e.g., “parents should teach their children that the family always comes first”); obligation familism (five items, e.g., “if a relative is having a hard time financially, one should help them out if possible”); referent familism (five items, e.g., “a person should always think about their family when making important decisions”); respect (eight items, e.g., “children should always be polite when speaking to any adult”); and religiosity (seven items, e.g., “parents should teach their children to pray”). Knight et al. (2010) demonstrated that these dimensions are substantially correlated and fit a higher order latent construct. For this study, the fit indices for the latent construct of Mexican American Cultural Values using these five dimensions provided a good fit in a confirmatory factor analysis at Time 1 [χ2 (5) = 4.44, p = 0.49, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00, and SRMR = .01] and Time 2 [χ2 (5) = 19.94, p <.05, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = .07, and SRMR = .02].

Prosocial Tendencies

To examine different types of prosocial behaviors, the Prosocial Tendencies Measure (PTM; Carlo and Randall 2002) was first administered at Time 3 (10th grade). The measure assesses 6 prosocial tendencies: compliant (2 items; α = .64, sample item: “When people ask me to help, I don’t hesitate”); emotional (4 items; α = .86, sample item: “Emotional situations make me want to help others in need”); dire (3 items; α = .76, sample item: “I tend to help people who are in a real crisis or need”); anonymous (5 items: α = .76, sample item, “I prefer to donate money without anyone knowing”); altruism (4 items; α = .75, sample item: “I feel that if I help someone, they should help me in the future”; note: all altruistic items were reverse coded), and public (4 items; α = .75, sample item: “I can help others best when people are watching me”). On a 5-point scale items range from 1 = does not describe me at all to 5 = describes me greatly. Prior research has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (including ethnic measurement equivalence) for Mexican Americans (e.g., Armenta et al. 2011; Carlo et al. 2010).

Analytic Plan

The longitudinal model was evaluated using structural equation modeling (SEM) in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén and Muthén 2010). Missing data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation (Arbuckle 1996; Schafer and Graham 2002). Although all variables were observed at the student level, students were clustered within 47 schools. However, the intraclass correlations (ICCs) for each variable in the model ranged from .00 to .03, suggesting that cluster effects within school was ignorable (i.e., no more that 3 % of the variance in any variable was attributable to school clustering).

To examine study hypotheses, we first examined the direct effects of T1 perceived discrimination on T3 prosocial tendencies (i.e., compliant, emotional, dire, anonymous, altruistic, and public). We then examined the direct effects of T1 perceived discrimination on T2 Mexican American values, controlling Mexican American values at T1. Mexican American values was modeled as a latent variable at T1 and T2 because this construct is comprised of five dimensions that are correlated substantially (Berkel et al. 2010; Knight et al. 2010), and our hypotheses were based on literature about Mexican cultural values generally rather than any single dimension of these values. We then examined how T2 Mexican American values related to T3 prosocial tendencies. As noted above, the prosocial tendencies measure was only available at T3. Finally, we conducted mediation analyses to examine potential indirect effects between discrimination and prosocial tendencies through its direct association with Mexican American values.

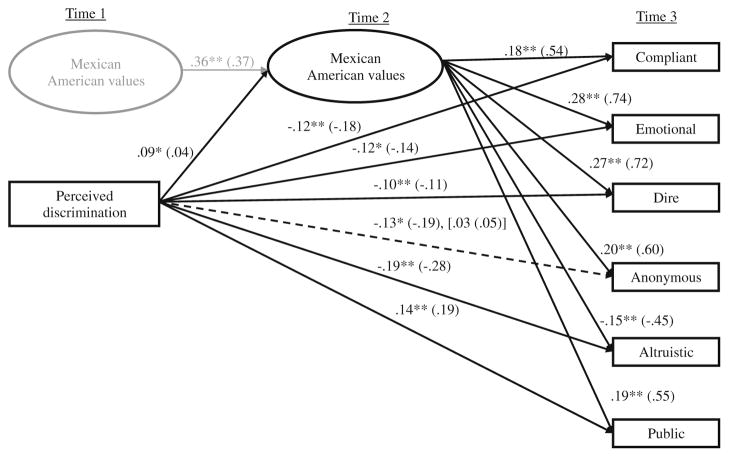

Multiple group analyses were used to test whether the mediation model varied across gender and adolescent nativity (e.g., US-born vs. Mexico-born). T1 and T2 Mexican American values were treated as latent constructs, while all other variables were treated as observed variables. The fit of the hypothesized SEM (see Fig. 1) was evaluated based on multiple fit indices because no single indicator is unbiased in all analytic conditions. Good (acceptable) model fit is reflected by Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA) less than .05 (.08), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) less than .05 (.08) (Hu and Bentler 1999; Kline 2005), and CFI values of 0.95 (0.90) or higher (Hoyle 1995; Kline 2005; Ullman 1996).

Fig. 1.

The relation of perceived discrimination to prosocial tendencies mediated by Mexican American values. All path coefficients are standardized (unstandardized path coefficients are reported in parentheses). The control variable is presented in solid grey. Significant paths are presented with a solid black line and the path that varies for males and females is presented with a dashed black line. The varying path estimates for males are presented in brackets. * p <.05, ** p <.01

Our test of the hypothesized model involved a number of steps: (a) an initial model was tested that allowed all estimated paths to vary across the two groups (e.g., males and females, US-born and Mexico-born) (i.e., fully free model); (b) a second model was conducted that tested for invariance in the estimated paths by constraining the paths to be equal across groups; (c) the fully free model was compared to the fully constrained (i.e., invariant) model using the Chi square difference test to determine if there were significant differences between the three groups, and follow-up tests (if needed) were conducted to determine paths that needed to be freely estimated across groups; (d) models were compared using the χ2 difference test. As there are no widely accepted alternatives to the χ2 change (Δχ2) test for comparing the fit of alternative models (Cheung and Rensvold 2002), especially when focusing on structural associations (Little et al. 2007), we used the Δχ2 test to compare the fit of nested models. If the Δχ2 test was significant, RMSEA and SRMR values were examined as additional indicators of model fit. Lower RMSEA and SRMR values indicate better fit with scores closer to zero indicating perfect fit (Hu and Bentler 1999). Mediation analyses were tested using the bias-corrected empirical bootstrap method recommended by MacKinnon et al. (2004) to construct confidence intervals that estimate indirect effects. Confidence intervals that do not contain a zero indicated significant mediation.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations of the observed study variables are presented in Table 1. Discrimination was associated positively with Mexican American values and public prosocial tendencies, whereas it was associated negatively with compliant, emotional, and altruistic tendencies. Mexican American values (T2) were related negatively to altruistic behaviors, whereas they were related positively to each of the other prosocial behaviors. Compliant, emotional, dire, anonymous, and public behaviors were all related positively to one another. Emotional, dire, anonymous, and public behaviors were associated negatively with altruistic behaviors. Means and standard deviations for the variables of interest by gender and nativity are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among study variables with means and standard deviations

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Discrimination T1 | – | ||||||||

| 2. Mexican American Values T1 | .05 | – | |||||||

| 3. Mexican American Values T2 | .10** | .32** | – | ||||||

| 4. Compliant T3 | −.10* | .14** | .15** | – | |||||

| 5. Emotional T3 | −.09* | .15** | .26** | .60** | – | ||||

| 6. Dire T3 | −.06 | .17** | .23** | .62** | .76** | – | |||

| 7. Anonymous T3 | −.04 | .10* | .18** | .42** | .48** | .51** | – | ||

| 8. Altruistic T3 | −.20** | .03 | −.16** | −.02 | −.13** | −.13** | −.19** | – | |

| 9. Public T3 | .15** | .06 | .18** | .20** | .20** | .31** | .22** | −.53** | – |

| Mean | 1.80 | 4.50 | 4.36 | 3.69 | 3.81 | 3.86 | 3.00 | 3.57 | 2.89 |

| SD | .62 | .33 | .33 | .92 | .78 | .79 | .90 | .90 | .89 |

p <.05,

p <.01

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of key variables by gender and nativity

| Gender

|

Nativity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female M (SD) | Male M (SD) | Mexico born M (SD) | US born M (SD) | |

| Discrimination T1 | 1.78 (.63) | 1.83 (.61) | 2.00 (.67)a | 1.72 (.58)b |

| Mexican American values T1 | 4.54 (.34) | 4.49 (.32) | 4.53 (.32) | 4.51 (.34) |

| Mexican American values T2 | 4.34 (.39) | 4.37 (.38) | 4.39 (.38) | 4.35 (.39) |

| Compliant T3 | 3.93 (.72) | 3.70 (.82) | 3.73 (.80)a | 3.84 (.77)b |

| Emotional T3 | 3.91 (.76)a | 3.80 (.81)b | 3.84 (.79) | 3.86 (.78) |

| Dire T3 | 3.75 (.95) | 3.62 (.88) | 3.52 (.95) | 3.75 (.90) |

| Anonymous T3 | 3.00 (.92) | 3.02 (.88) | 2.88 (.91)a | 3.06 (.89)b |

| Altruistic T3 | 3.78 (.85)a | 3.36 (.89)b | 3.59 (.87) | 3.56 (.91) |

| Public T3 | 2.73 (.93)a | 3.02 (.82)b | 2.84 (.84) | 2.89 (.91) |

Letters denote significant mean level differences at p <.05. Superscripts within a group’s column that differ from one another within the same row represent significant mean level differences between groups

Test of Direct Effects

Results of the SEM analysis indicated that the fit of the model was good [χ2 (97) = 328.4, p <.001; CFI = 0.95; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.04; Fig. 1]. T1 discrimination was related positively to T2 Mexican American values (β = .09, p <.05) and T3 public (β = .14, p <.01) prosocial tendencies, whereas T1 discrimination was linked negatively to T3 compliant (β = −.12, p <.01), T3 emotional (β = −.12, p <.05), dire (β = −.10, p <.01), and T3 altruistic (β = −.19, p <.001) prosocial tendencies. T2 Mexican American values predicted positively T3 compliant (β = .18, p <.001), T3 emotional (β = .28, p <.001), T3 dire (β = .27, p <.001), T3 anonymous (β = .20, p <.001) and T3 public (β = .19, p <.001) prosocial behaviors, whereas it predicted negatively T3 altruistic (β = −.15, p <.001) prosocial tendencies.

Test of Mediator

Several modest significant mediation effects were found for five of the six pathways to prosocial tendencies (direct, indirect, and total effects are reported in Table 3). Specifically, the test of the mediated effects using bias corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (MacKinnon et al. 2002) were significant for T3 compliant (Indirect effect = .015, 95 % CIs = .006, .049), T3 emotional (Indirect effect = .025, 95 % CIs = .005, .061), T3 dire (Indirect effect = .024, 95 % CIs = .006, .061), T3 anonymous (Indirect effect = .017, 95 % CIs = .004, .052), and T3 public (Indirect effect = .016, 95 % CIs = .003, .051) prosocial tendencies. This is an indication of inconsistent mediation such that although T1 perceived discrimination was linked directly and negatively to most T3 prosocial tendencies, it was related positively to adolescents’ T2 Mexican American values, which were related positively to T3 prosocial tendencies.

Table 3.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of perceived discrimination and Mexican American values on adolescents’ prosocial tendencies

| Predictor | Mexican American values (T2) | Prosocial tendencies (T3)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliant | Emotional | Dire | Anonymous | Altruistic | Public | ||

| Mexican American values (T1) | |||||||

| Direct effect | .36** | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Indirect effects | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total effects | .36** (.32**) | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mexican American values (T2) | |||||||

| Direct effect | n/a | .18** | .28** | .27** | .20** | −.15** | .19** |

| Indirect effects | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total effects | .18** (.15**) | .28** (.26**) | .27** (.23**) | .20** (.18**) | −.15** (−.16**) | .19** (.18**) | |

| Perceived discrimination (T1) | |||||||

| Direct effects | .09* | −.12** | −.12* | −.10** | −.06 | −.19** | .14** |

| Indirect effect | n/a | .02* | .03* | .03* | .02* | −.03 | .02* |

| Total effects | .09* (.10**) | −.10* (−.10*) | −.09* (−.09*) | −.07 (−.06) | −.04 (−.04) | .21*** (−.20**) | .15*** (.15**) |

The reported indirect effects are through either single or multiple mediator variables specified in the model. Correlations are shown in parentheses.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01

Moderation by Gender

We tested whether the path estimates in the longitudinal mediation model differed by adolescent gender by using multiple group SEM analyses to first estimate a fully unconstrained model in which all paths were allowed to vary across gender, and then a model in which all paths were constrained to be equal. We utilized the Chi square difference test to evaluate whether there were significant differences between the unconstrained model and constrained model. The practical fit indices for the unconstrained model were: χ2 (210) = 469.77, p <.05, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .08. The practical fit indices for the constrained model were: χ2 (224) = 496.23, p <.05, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .08. The Chi square difference test for the comparison across genders was significant [Δχ2 (14) = 26.46, p <.05], even though the practical fit indices were not different, suggesting that some small paths differences across genders. The modification indices of the fully constrained model suggested that the path from perceived discrimination to anonymous prosocial tendencies should be freed. Therefore, a partially constrained model was tested that constrained all of the path coefficients across gender except that from perceived discrimination to anonymous prosocial tendencies. The fit indices for the partially constrained model were: χ2 (223) = 490.80, p <.05, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = .06, and SRMR = .08. In comparing the partially constrained model to the fully unconstrained model, the Chi square difference was not significant [Δχ2 (13) = 21.03, ns] suggesting that only the path from perceived discrimination to anonymous prosocial tendencies was significantly different for males and females; mainly, perceived discrimination was related negatively to anonymous helping for girls, and this association was not significant for boys. Therefore, the partially constrained model was selected as the best model due to parsimony. Hence, the path model depicted in Fig. 1 was the same for males and females, with the exception of this one path coefficient.

Moderation by Nativity

We tested whether the path estimates in the mediation model differed by adolescent nativity (born in the Unites States versus born in Mexico) by using multiple group SEM analyses to first estimate a fully unconstrained model in which all paths were allowed to vary across nativity, and then a model in which all paths were constrained to be equal. We utilized the Chi square difference test to evaluate whether the unconstrained and constrained models fit the data differently. The practical fit indices for the unconstrained model were: χ2 (210) = 446.17, p <.05, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = .06 and SRMS = .05. The practical fit indices for the constrained model were: χ2 (224) = 451.93, p <.05, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = .05 and SRMS = .06. The Chi square difference test for the comparison across nativity was not significant [Δχ2 (14) = 5.76, ns], the practical fit indices associated with the constrained and unconstrained models were not substantially different, and none of the path estimates across nativity groups appeared to be meaningfully different. Hence, the path model depicted in Fig. 1 was not moderated meaningfully by the adolescents’ nativity.

Discussion

Experiencing discrimination may be common in Mexican American youths’ lives, especially in southwest regions of the United States where reports of hate crimes towards Latinos have been on the rise (Federal Bureau of Investigation 2010). Some youth may react to discrimination in problematic ways, such as through substance use (Vega and Gill 1998) or through internalizing and externalizing behaviors (e.g., Sellers et al. 2003; Stevenson 1997; Wong et al. 2003). However, other youth may react to stressful ethnic experiences, such as perceived discrimination, in ways that provide resistance to, or resilience in light of, those stressors (Ginwright 2007). Therefore, the current study examined the direct and indirect effects of perceived discrimination, on the development of prosocial tendencies among Mexican American adolescents. Furthermore, we tested the hypothesis that Mexican American values would serve as a mediator between perceived discrimination and six types of prosocial tendencies.

Perceived Discrimination and Prosocial Tendencies

Adding support to social exclusion theory (e.g., DeWall and Baumeister 2006; Richman and Leary 2009; Twenge et al. 2007), we found negative associations between perceived discrimination reported by Mexican American youth and most types of prosocial tendencies. It appeared that perceived discrimination was associated with reduced intentions to help in compliant, emotional, dire, and altruistic circumstances. This may be due to that fact that helping others is taxing to one’s sense of self when one perceives that others are discriminatory. The fact that perceived discrimination was related to public helping negatively is also consistent with previous theory (Richman and Leary 2009), suggesting that when people experience discrimination, they may be more likely to engage in behaviors that make their group look more favorable in the public eye. On the other hand, it is also possible that adolescents’ public helping is a precursor to adult engagement in issues of social justice (O’Leary and Romero 2011). Therefore, one direction for future research is to examine associations between experiences with discrimination and engagement in different types of public helping, such as advocacy or civic involvement.

The Mediating Role of Mexican American Values

It is not surprising that experiencing perceived discrimination was associated with a stronger endorsement of Mexican American values. Studies show that experiences with discrimination prompt youth to explore and come to a clear understanding of what it means to be a member of an ethnic group (e.g., Greene et al. 2006). As part of this process of examining and strengthening one’s affiliation with one’s ethnic group, it is likely that adolescents develop a stronger connection to their cultural heritage and customs. Perhaps youth who believe that society discriminates against their ethnic group will cling more closely to their community and thereby endorse Mexican American values more strongly. However, we believe that the benefits of Mexican American values for prosocial tendencies extend beyond merely protecting youth from risk (e.g., Branscombe et al. 1999). It has been argued from a developmental perspective that affiliation with one’s ethnic group precedes the search for meaning around one’s ethnicity, which in turn directly leads to the formation of youths’ prosocial development (Knight et al. 1993).

In the current study, Mexican American values emerged as one mechanism through which youths’ positive development may be fostered in light of ethnic-related stress. Specifically, associations between perceived discrimination and most prosocial tendencies were mediated by youths’ Mexican American values. Namely, results suggested that perceived discrimination at Time 1 contributed to an increase in Mexican American values at Time 2, which, in turn had a compensatory relationship with most of the prosocial tendencies. In most cases, the direction of the relation between Mexican American values and prosocial behaviors was opposite that of the relationship between discrimination and these tendencies; altruistic and public prosocial tendencies were exceptions.

Development scholars who study prosocial behaviors have noted that specific forms of prosocial behaviors can be motivated to either promote the welfare of others or to promote one’s own welfare (Batson 1998; Carlo 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2006). The emphases on the family group and interdependence may help to preserve prosocial tendencies that benefit others (such as those in compliant, dire, emotional, and anonymous situations) in the face of adversity from discrimination experiences. It has been further suggested that cultural values provide Mexican American youth with a dispositional prosocial orientation that may begin with exhibiting helping behaviors within the family context in childhood but that provide a basis for extending helping behaviors beyond the family to peers and community among adolescents (Knight and Carlo 2012). While these assumptions are theoretically based, the current study highlights one avenue for future research, that is, to investigate the role of ingroup and outgroup affiliations as they relate to Mexican American adolescents’ prosocial development and helping behaviors.

The positive association between perceived discrimination and public helping was strengthened by the positive links between Mexican American values and public helping. Mexican American individuals who experience discrimination and who endorse traditional cultural values may be more likely to express public helping as a means of gaining approval from others, and in turn promoting their own welfare (Carlo and Randall 2002). Similarly, the negative relationship between perceived discrimination and altruistic behaviors was strengthened by a negative relationship between Mexican American values and these tendencies. The fact that there was no mediating effect on altruistic prosocial tendencies may be consistent with previous research that suggests that altruistic tendencies often are expressed by individuals with specific personal characteristics, such as high levels of sympathy or strongly internalized principles, rather than connection to specific cultural values (Carlo 2006; Eisenberg et al. 2006).

In the current study, we have investigated one factor that affects Mexican American youths’ positive development (i.e., perceived discrimination), in order to understand how risk and resilience (prosocial tendencies through Mexican American values) transpires among this population of youth. However, we posit that it is important to understand other factors that inform Mexican American youths’ cultural values as well. For example, families provide one social context through which adolescents’ cultural heritage is promoted (Parke and Buriel 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al. 2009); however, peers and youth development programs are additional social contexts that are important for adolescent development and they have received little attention in the literature regarding cultural socialization.

Moderation by Gender and Nativity

Finally, the processes relating discrimination with prosocial behaviors functioned the same for males and females generally, with the exception of the direct associations between perceived discrimination and anonymous helping (negative association for girls, not significant for boys). Anonymous helping, such as assisting when one’s identity is unknown to the recipient, may be important to Mexican American families because studies suggest that this type of helping demonstrates other culturally endorsed values, such as humility and collectivism (Oyserman et al. 2002; Suizzo 2007). In addition, gender socialization (e.g., teaching girls to be accommodating and obedient; Jolicoeur and Madden 2002) is a common practice in some Mexican American families (Raffaelli and Ontain 2004). It is possible that perceived discrimination has more of an impact on girls’ anonymous helping because of their expectations to be helpful in different social situations. On the other hand, boys’ anonymous helping may not be as threatened severely by perceived discrimination because of differential expectations to help strangers. However, given that this is first study of its kind to examine the associations between discrimination and different types of prosocial tendencies in a longitudinal study of adolescents, further research is needed to determine if these gender differences replicate.

Regarding nativity, the processes functioned the same for US-born and Mexico-born adolescents. Therefore, although youth born in the United States compared those born in Mexico may vary on individual characteristics (e.g., perceived discrimination was higher among US-born adolescents compared to Mexico-born adolescents and compliant helping was higher among Mexico-born adolescents compared to US-born adolescents), the process through which Mexican American values mediated the effect of perceived discrimination on prosocial tendencies was the same. In response to the call for research that investigates how resilience is promoted among Mexican American youth (e.g., García Coll et al. 1996; Quintana et al. 2006), the current study has highlighted the protective role of Mexican American values for Mexican American males and females and youth varying in country of origin.

Limitations, Directions for Future Research, and Conclusion

Though this research had several strengths, including being the first to use longitudinal data to test the associations between perceived discrimination and prosocial tendencies, there were several limitations that should be noted. The association between T1 perceived discrimination and T2 Mexican American values may have appeared relatively small; however, it should be noted that this association was identified accounting for developmental change in Mexican American values over a two-year period (from 5th and 7th grade). Furthermore, the current study examined the prospective effects of adolescents’ perceived discrimination in 5th grade on Mexican American values in 7th grade. Another limitation to note is that longitudinal data on adolescents’ prosocial tendencies were not available at T1 or T2 (i.e., the prosocial measure was first introduced at T3 and therefore, we were not able to control for prior levels of prosocial behaviors). Given that earlier data on prosocial tendencies were not yet available for the current study, we were unable to address the possibility of reverse directionality. Therefore, future longitudinal studies would benefit from examining the development of prosocial tendencies in tandem with experiencing discriminatory events to determine how discrimination may influence the development of prosocial tendencies over time. Third, as the current study focused on the role of Mexican American values as a mediator among a sample of Mexican American adolescents in a Southwest region of the United States, the results of the current study may not generalize to other Latino populations or individuals from other geographic locations. Therefore, one direction for future research is to examine how this process functions for youth in schools and neighborhoods that vary by racial and ethnic demographics. Moreover, the data in the current study were derived from self-report and survey-based measures. Future studies may want to consider the inclusion of multiple reporters (e.g., parents and teachers), measures of social desirability, or observational data in assessing the development of adolescents’ prosocial behaviors.

Our findings have implications for practice, policy, and culturally informed prevention programs. Results from the current study indicated that perceived discrimination experienced in late childhood (5th grade) was associated negatively with prosocial tendencies in middle adolescence (10th grade). However, we have highlighted the protective function of Mexican American values for this population of youth. Therefore, prevention and positive youth development programs may want to consider cultivating Mexican American youths’ cultural values as part of their curriculum for prosocial development. Regarding policy, our measure of perceived discrimination captured interactions with teachers and peers suggesting that schools are one social context where Mexican American youth experience discrimination. This is consistent with previous research on discrimination in schools (Greene et al. 2006; Wang and Huguley 2012), and suggests that schools may want to further develop or implement policies and training around cultural sensitivity and unity in the school context to help reduce youths’ experiences with discrimination.

To summarize, the current study advances theory on adolescents’ resilience and prosocial development by examining how perceived discrimination may influence adolescents’ intentions to help in various social situations. The current study lends support for Mexican American values as an important person characteristic present in the lives of Mexican American youth that may promote resilience. Understanding the role of perceived discrimination and youths’ cultural orientation is an important task for assessing diverse youths’ positive development. In addition, it may be important for researchers, educators, and practitioners to consider the culturally based strengths of youth as the United States becomes more diverse.

Acknowledgments

The current study was funded by NIH Grant MH68920 (Culture, context, and Mexican American mental health; Proyecto: La Familia [The Family Project]). Writing of this report was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health Training Grant (T32 MH018387; PI: Chassin). We thank Marisela Torres and Jaimee Virgo, the interviewers, the Community Advisory Board, and the La Familia Team for their participation in this study. We also appreciatively acknowledge the youth and families who participated in this research.

AB conceived of the current study, participated in its design and coordination, performed statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. MO participated in the current study design and performed statistical analyses. GK participated in the current study design and provided scientific knowledge on theory and statistical analysis, and contributed to the design of Proyecto: La Familia. GC provided scientific knowledge on theory for the manuscript. AUT contributed to the design of Proyecto: La Familia, provided scientific feedback and helped to draft the manuscript. MR is the Principal Investigator of Proyecto: La Familia, provided scientific feedback and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Biographies

Aerika S. Brittian Ph.D. is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She received a doctoral degree in 2010 from Tufts University. Her research interests include investigating risk and protective factors among ethnic minority youth and families, and making recommendations for culturally informed practice and prevention. Her current line of research investigates how experiences with ethnic discrimination relate to African American and Latino youths’ psychological and psychosocial outcomes, and both the person-centered (ethnic-racial identity, coping) and contextual-level factors (ethnic socialization, cultural values) that alter youths’ developmental trajectories.

Megan O’Donnell is a doctoral candidate in the Family and Human Development program at Arizona State University (ASU). She currently teaches statistics at ASU; her research interests include cultural-related stressors, coping, and acculturation processes in Latino adolescents.

George P. Knight Ph.D. is a Professor in the Department of Psychology at Arizona State University. He received a doctoral degree from the University of California at Riverside. His research interests have focused on the role of culture in prosocial development, acculturation and enculturation processes, the development of ethnic identity, and measurement equivalence in cross-ethnic and developmental research.

Gustavo Carlo Ph.D. is the Millsap Professor of Diversity in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of Missouri-Columbia. He received a doctoral degree in 1994 from Arizona State University. His research interests include prosocial and moral development among children and adolescents, temperament, family correlates, social cognitions and emotions, culture-related variables associated with such development, and positive health and adjustment among Latino families and youth.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor Ph.D. is a Professor in the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. She received her PhD in 2001 from the University of Missouri-Columbia. She uses an ecological approach to inform her research, taking into account how individuals and families influence and are influenced by their surrounding ecologies. Her research focuses on ethnic identity formation during adolescence, parent-adolescent relationships, and cultural risk and protective factors. With regard to ethnic identity formation, she is exploring the different components that define one’s ethnic identity, as well as the factors that influence these components. Her research seeks to uncover how adolescents develop their identities, the roles that significant socialization agents and contexts play in this process, and how ethnic identity is associated with important variables (e.g., family relationships, academic success, psychological functioning).

Mark W. Roosa Ph.D. is a Professor in the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. He received a doctoral degree in 1980 from Michigan State University. His research interests include etiological processes that place children at risk or protect children from risk and the additive and interactive roles of culture and context in influencing child outcomes.

Contributor Information

Aerika S. Brittian, Email: brittian@uic.edu, Department of Educational Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago, 1040 W. Harrison St. (mc 147), Chicago, IL 60607, USA

Megan O’Donnell, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA.

George P. Knight, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Gustavo Carlo, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO 64110, USA.

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

Mark W. Roosa, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

References

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Knight GP, Carlo G, Jacobson RP. The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;41:107–115. doi: 10.1002/ejsp. 742. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998. pp. 282–316. [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J-Y, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, et al. Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;20:893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.006 68.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal ME, Knight GP, Ocampo KA, Garza CA, Cota MK. Development of Mexican American identity. In: Bernal MA, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among hispanics and other minorities. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1993. pp. 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African-Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calderón-Tena CO, Knight GP, Carlo G. The socialization of prosocial behavior tendencies among Mexican American adolescents: The role of familism values. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:98–106. doi: 10.1037/a0021825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G. Care-based and altruistically based morality. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 551–579. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Fabes RA, Laible D, Kupanoff K. Early adolescence and prosocial/moral behavior II: The role of social and contextual influences. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:133–147. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Knight GP, McGinley M, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. The multidimensionality of prosocial behaviors and evidence of measurement equivalence in Mexican American and European American early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2010;30:334–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00 637.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, McGinley M, Hayes RC, Martinez MM. Empathy as a mediator of the relations between parent and peer attachment and prosocial and physically aggressive behaviors in Mexican American college students. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;29:337–357. doi: 10.1177/0265407511 431181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Randall BA. The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:31–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1014033032440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing MI. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:235–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Updegraff KA, Roosa MW, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Perceived discrimination and Mexican-origin youth adjustment: The moderating roles of mothers’ and fathers’ cultural orientations and values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall CN, Baumeister RF. Alone but feeling no pain: Effects of social exclusion on physical pain tolerance and pain threshold, affective forecasting, and interpersonal empathy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1–15. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards L, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent youth. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:24–39. doi: 10.1177/0739986307311431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller PA, Shell R, McNalley S, Shea C. Prosocial development in adolescence: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:849–857. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Guthrie IK, Murphy BC, Shepard SA. Age changes in prosocial responding and moralreasoning in adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2005;15:235–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Prosocial development. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 5. New York: John Wiley; 1998. pp. 701–778. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Spinrad TL. Prosocial development. In: Eisenberg N, editor. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Morris AS, McDaniels B, Spinrad TL. Moral cognitions and prosocial responding in adolescence. In: Steinberg I, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 229–265. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Carlo G, Kupanoff K, Laible D. Early adolescence and prosocial/moral behavior I: The role of individual processes. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Hate crimes statistics. 2010 Retrieved on December 5, 2011 from: http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/hate-crime/2010/narratives/hate-crime-2010-victims.

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. doi: 10.1023/A:1026455906512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores E, Tschann JM, Dimas JM, Bachen EA, Pasch LA, de Groat CL. Perceived discrimination, perceived stress, and mental and physical health among Mexican-origin adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:401–424. doi: 10.1177/0739986308323056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, Garcia HV, et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb018 34.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright S. Black youth activism and the role of critical social capital in Black community organizations. American Behavioral Scientist. 2007;51:403–418. doi: 10.1177/0002764207306 068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Germán M, Kim SY, George P, Fabrett FC, Millsap R, et al. Mexican American adolescents’ cultural orientation, externalizing behavior and academic engagement: The role of traditional cultural values. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:151–164. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9152-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-16 49.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L, Ispa J, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle R. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1023066418 688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Dodge MA. African American women in the workplace: Relationships between job conditions, racial bias at work, and perceived job quality. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1997;25:581–599. doi: 10.1023/A:1024630816168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolicoeur PM, Madden T. The good daughters: Acculturation and caregiving among Mexican American women. Journal of Aging Studies. 2002;16:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Carlo G. Prosocial development among Mexican American youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:258–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, Bernal ME. The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1993;15:291–309. doi: 10.1177/07399863930153001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Gonzales NA, Saenz DS, Bonds D, Germán M, Deardorff J, et al. The Mexican American cultural values scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30:444–481. doi: 10.1177/0272431609338178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. doi: 10.1177/00957984960222002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Card NA, Slegers D, Ledford E. Representing contextual factors in multiple-group MACS models. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley M, Carlo G, Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, Torres Stone RA, Iturbide MA. Stressed and helping: The relations among acculturative stress, gender, and prosocial tendencies in Mexican Americans. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;150:34–56. doi: 10.1080/00224540903365323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus (Version 6.00) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary AO, Romero AJ. Chicana/o students respond to Arizona’s anti-ethnic studies bill, SB 1108: Civic engagement, ethnic identity, and well-being. Aztlan: A Journal of Chicano Studies. 2011;36:9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman D, Coon HM, Kemmelmeier M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:3–72. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.128.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ecological and ethnic perspectives. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 429–504. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(4):531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among US Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Aboud FE, Chao RK, Contreras-Grau J, Cross WE, Jr, Hudley C, et al. Race, ethnicity, and culture in child development: Contemporary research and future directions. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1129–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624. 2006.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 2004;50:287–299. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.000001 8886.58945.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin JL, Lane DJ, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Adolescent self-consciousness: Longitudinal age changes and gender differences in two cohorts. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:1–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2004.014010 01.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Leary MR. Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review. 2009;116:365–383. doi: 10.1037/a0015250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez J, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Smith EP, Johnson DJ. Cultural processes in parenting and youth outcomes: Examining a model of racial-ethnic socialization and identity in diverse populations. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15:106–111. doi: 10.1037/a0015510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, Roberts RE. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33(11):2288–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01885.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Liu FF, Torres M, Gonzales NA, Knight GP, Saenz D. Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:293–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Wolchik SA, Sandler IN. Preventing the negative effects of common stressors: Current status and future directions. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 515–535. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. doi: 10.1037//1082-989X.7.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Zamboanga B, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behavior, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Burnett S, Blakemore S. Development of the self-concept during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:302–317. doi: 10.2307/1519781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, Lewis RL. Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in African American adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16:187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrod LR, Lauckhardt J. The development of citizenship. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. 3. Vol. 2. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 372–408. Contextual influences on adolescent development. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC., Jr Missed, dissed, and pissed: Making meaning of neighborhood risk, fear and anger management in urban Black youth. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health. 1997;3:37–52. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.3.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suizzo MA. Parents’ goals and values for children: Dimensions of independence and interdependence across four US ethnic groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2007;38:506–530. doi: 10.1177/0022022107302365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of intergroup relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Bartels JM. Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:56–66. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman J. Structural equation modeling. In: Tabachnick BG, Fideli LS, editors. Using multivariate statistics. 3. New York, NY: Harper Collins College Publishers; 1996. pp. 709–811. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining a model of ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the US. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. doi: 10.1177/0739986303262143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Wong JJ, Gonzales NA, Dumka LE. Ethnic identity and gender as moderators of the associations between discrimination and academic adjustment among Mexican-origin adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gill AG. A model for explaining drug use behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Drugs & Society. 1998;14:57–74. doi: 10.1300/J023v14n01_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Huguley JP. Parental racial socialization as a moderator of the effects of racial discrimination on educational success among African American adolescents. Child Development. 2012;83:1716–1731. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff AJ. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African-Americans adolescents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-64 94.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]