Abstract

Magnetoelectric multiferroics are materials that have coupled magnetic and electric dipole orders, which can bring novel physical phenomena and offer possibilities for new device functions. In this report, single-crystalline Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts which are isostructural with the high-temperature superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ are successfully grown by a hydrothermal method. The regular stacking of the rock salt slabs and the BiFeO3-like perovskite blocks along the c axis of the crystal makes the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts have a natural magnetoelectric–dielectric superlattice structure. The most striking result is that the bulk material made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts is of multiferroicity near room temperature accompanied with a structure anomaly. When an external magnetic field is applied, the electric polarization is greatly suppressed, and correspondingly, a large negative magnetocapacitance coefficient is observed around 270 K possibly due to the magnetoelectric coupling effect. Our result provides contributions to the development of single phase multiferroics.

The layered ferroelectric–dielectric (FE–DE) superlattices currently attract a considerable attention due to potential technological applications and novel fundamental physics1. The performance of a ferroelectric layer can be significantly improved by combining with a dielectric layer in a carefully tailored lattice2, and a polarization can be induced in a sufficiently polarizable dielectric layer via electrostatic coupling1,3. Some of the FE–DE superlattice-structured thin films have been successfully constructed experimentally, such as PbTiO3–SrTiO3, BaTiO3–SrTiO3, and BiFeO3–SrTiO3 superlattices3,4,5. In particular, for the BiFeO3–SrTiO3 superlattice, the conventional ferroelectric layers are replaced by multiferroic BiFeO3 layers to form a magnetoelectric–dielectric (ME–DE) superlattice structure, thus a magnetic order parameter can be imported into the system, which may open a new route for achieving magnetoelectrically tunable logic devices6,7,8. However, high-quality multilayer superlattice thin films are in general difficult to be synthesized due to not only a complex fabrication procedure but also the degeneration of the ferroelectric properties5,9. Therefore, it should be more interesting if one can design and grow a natural layered compound with the analogous ME–DE superlattice. In this case, an intrinsic magnetoelectric effect would stand out more obviously because of the naturally improved interfaces between ME and DE layers. In fact, there have been a few ferroelectric Aurivillius compounds, approximately having the natural FE–DE layered structure, for example, SrBi2Ta2O9 (SBT), presenting a superior fatigue resistance and being widely used in ferroelectric random access memories (FeRAM)10. Moreover, a room temperature multiferroic behavior is achieved in Aurivillius-structured Bi5Fe0.5Co0.5Ti3O15 ceramics by substituting magnetic transition metal ions11, implying a quasi–ME–DE superlattice may be formed.

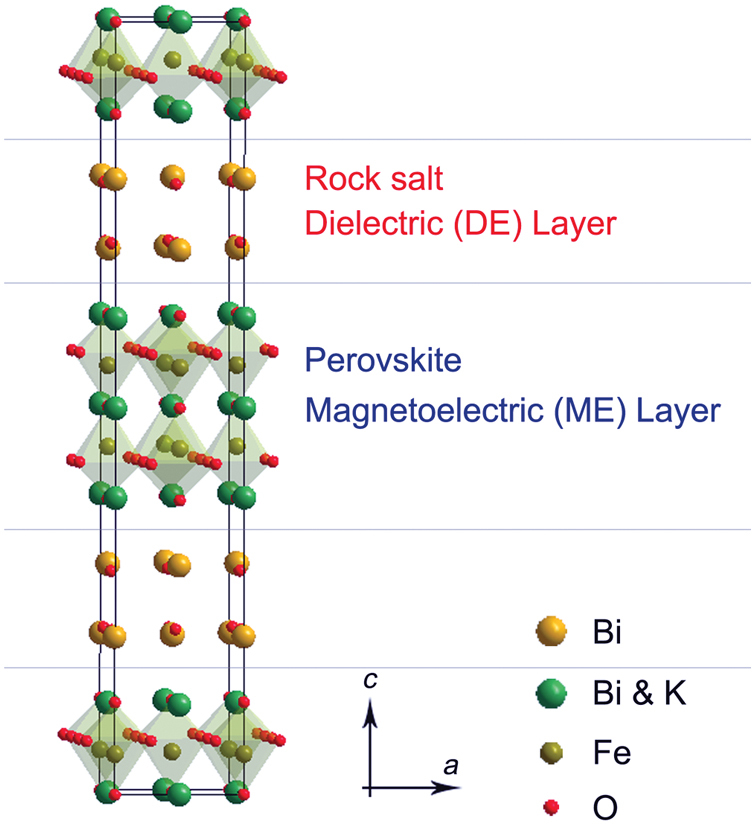

In the light of the above, the abundant bismuthal oxides with a layered structure can be a good candidate class as the point of breakthrough. It is known that the high-temperature superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ (Bi2212) is a representative layered compound with a “…– perovskite layer – rock salt layer – perovskite layer – rock salt layer – …” regular alternating arrangement along the c axis of the crystal12. The insulating rock salt [Bi2O2]2+ slab can be regarded as a good dielectric layer, thus on condition that the conductivity perovskite blocks in Bi2212 are replaced by multiferroic ones, a ME–DE superlattice would come true and it should be very useful for understanding the intrinsic multiferroic properties of a single phase material13,14.

According to this point of view, we design a multiferroic compound via replacing all the Sr and Ca ions by Bi ions and all the Cu ions by Fe ions on the basis of the structure of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ. As a result, the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts with perovskite layers similar to the well-known multiferroic BiFeO3 blocks are obtained, and thus a prospective ME–DE superlattice is achieved. The most important results are that not only weak ferromagnetism and ferroelectricity are observed, but also a huge negative magnetocapacitance effect occurs near room temperature in the bulks made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts. The ferroelectric polarization of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts can be suppressed by magnetic fields via magnetoelectric coupling. It is notable that the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ compound cannot be synthesized by a conventional solid state reaction method (see Supplementary Information), and it only can be grown within a nanoscale through a hydrothermal method so far.

Results

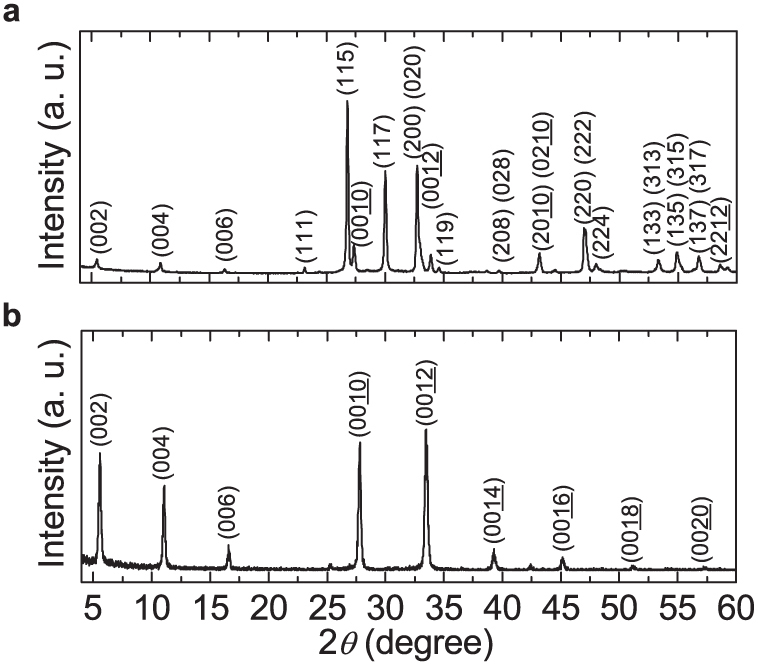

Figure 1 shows X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts. For the data in Fig. 1a, the nanobelts have been fully ground to reduce the preferred orientation from the belt-like shape. The diffraction patterns are similar to that of the Bi2212 as well as its isostructural compound Bi2+xSr3−xFe2O9+δ (BSFO, JCPDS card No. 86-0286)15,16, and the lattice parameters are about a = 5.470 Å, b = 5.468 Å, c = 32.592 Å (space group Fmmm) for the average structure. Meanwhile, if the as-synthesized nanobelts are laid flat on a substrate with no grind, the intensity of the (00l) diffraction patterns increases markedly, and the diffraction patterns of the other directions almost disappear as shown in Fig. 1b. These results demonstrate that the samples may have a good single-crystalline structure with the c axis perpendicular to the surface plane of the nanobelts. In addition, the structure of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts is long-term stable at room temperature, but when heated to about 720 K, the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts will be decomposed mainly to BiFeO3 and Bi2O3(KBiO2)x, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Figure 1. X-ray diffraction patterns of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at room temperature.

(a) The nanobelts were adequately ground with no preferred orientation. (b) The nanobelts were laid as flat as possible on a substrate without any grind.

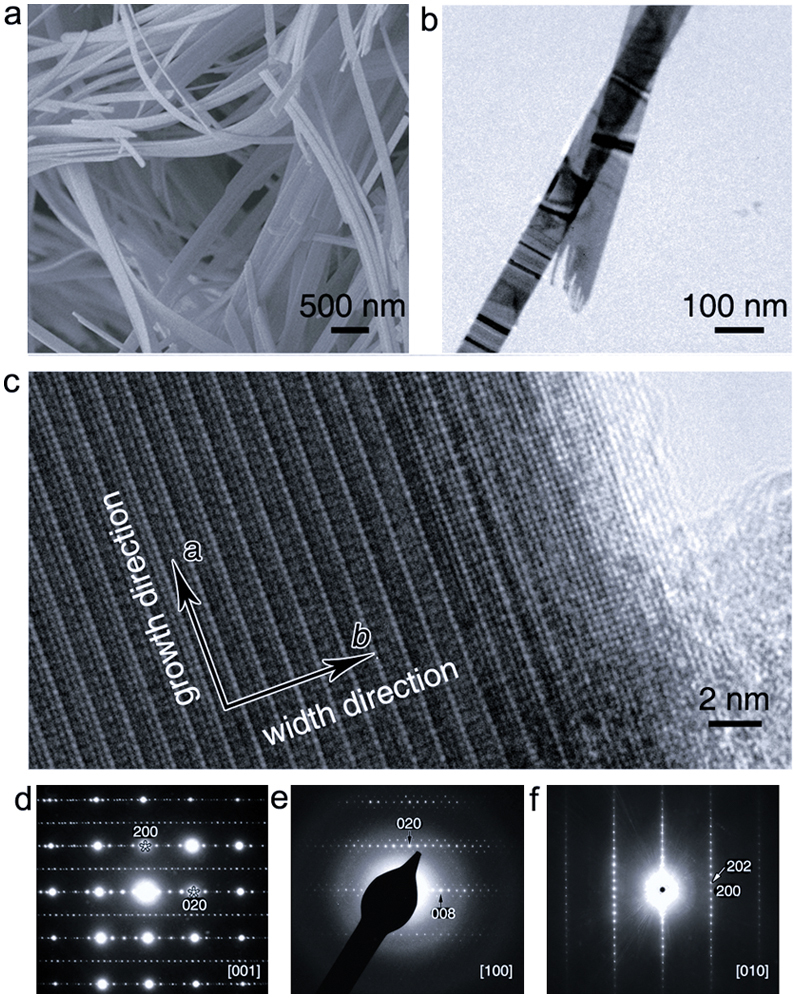

To further examine the structure, the microstructure of the sample is investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Figs. 2a and 2b show the overview images of the nanobelts, the lengths of the nanobelts vary from a few to several dozen micrometers and more morphology images can be seen in Supplementary Fig. S2. The energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) analyses on each single nanobelt reveal the presence of Bi, K and Fe with an average atomic ratio close to 4.2:0.8:2 (see Supplementary Fig. S3), and K ions are introduced to the lattice by self-assembly during the hydrothermal process, which may be helpful to keep the structure and chemical valences steady. Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. S4 show the high-resolution TEM images focusing on the surface plane of a nanobelt, it is noted that the nanobelts grow along [100] direction (a-axis) and have a commensurately modulated structure with 4 time periodicity of the subcell lattice parameter b, which can be also confirmed from the result of selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns along the [001] and [100] zone axes as displayed in Figs. 2d and 2e. From the satellite spots in Fig. 2e the modulation can finally be characterized by a wave vector q* = (0, 0.25, 1). Fig. 2f presents the SAED patterns of the [010] zone axis of a single nanobelt, in which the satellite spots are invisible due to the projection direction. It can be inferred the structural modulate wave make the <100> facets have higher surface energy than the <010> facets. Since the <001> facets have the lowest surface energy due to the large BiO interlayer distance10, thus a belt-like structure is forming. Taken together, a nanosized single crystal is obtained through our synthetic route, and their average structure constructed by analyzing the XRD, SAED patterns and high-resolution TEM images, is shown in Fig. 3 without considering the modulated structure, and the calculated XRD patterns based on this preliminary structure model using a Rietveld method are presented in Supplementary Fig. S5, which basically agrees with experimental points. Hence the structure of the nanobelts could be of the “… – perovskite layer – rock salt layer – perovskite layer – rock salt layer – …” configuration along the c axis of the crystal and one can find the perovskite layer is similar to the structure of BiFeO317,18, indicating a possibility for multiferroic characteristics.

Figure 2. Morphology characterizations of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts.

(a–c) Scanning electron microscopy (a), bright-field transmission electron microscopy (b), and [001] zone axis high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (c) images of the nanobelts. (d–f), [001] (d), [100] (e), and [010] (f) zone axes selected area electron diffraction patterns (SAED) of the nanobelts, and a commensurately modulated wave vector q* = (0, 0.25, 1) can be confirmed.

Figure 3. Average structure scheme of Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ.

The structure of the new compound is constructed through the analysis of characterization results, and is isostructural with the high-temperature superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ, which make it have a natural magnetoelectric–dielectric superlattice configuration along the c axis of the crystal.

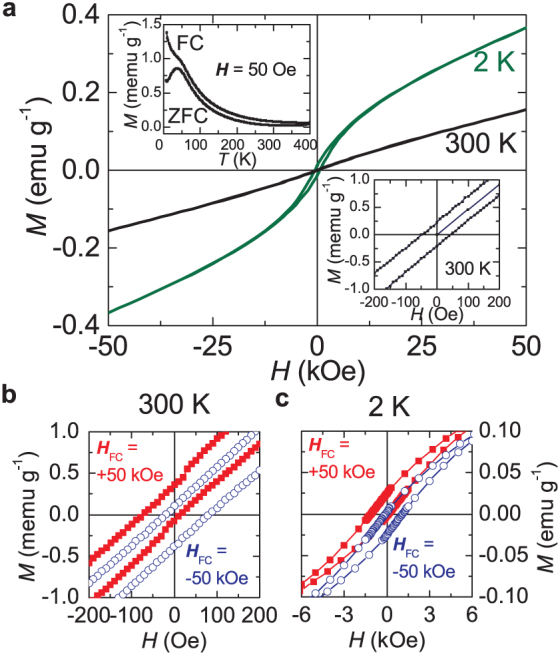

Figure 4a shows the magnetic hysteresis loops of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at 300 K and 2 K. At room temperature, the magnetization (M) – applied magnetic field (H) curve is almost linear between −50 kOe and +50 kOe with a small coercive magnetic field (HC) about 50 Oe. This implies the magnetic ground state of Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ may be antiferromagnetic accompanied with weakly ferromagnetically coupled spins possibly located at the surface of the nanobelts, bringing a weak ferromagnetism to the system19. At 2 K, a more obvious hysteresis loop with a HC of about 600 Oe indicates the ferromagnetism is enhanced at low temperatures. The top inset of Fig. 4a shows the temperature (T) dependencies of zero field cooled (ZFC) and field cooled (FC) magnetizations at 50 Oe for the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts. The ZFC curve shows a peak near Tp = 40 K and a separation from the FC curve below Tp, indicating the appearance of spin-glass-like behavior at low temperatures. It is notable that an exchange bias phenomenon is observed in Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at 300 K and 2 K when M–H curves are measured in the FC mode with the cooling fields HFC = ±50 kOe as shown in Figs. 4b and 4c, which could be explained by the exchange coupling between the inside antiferromagnetic spins and the surface ferromagnetic-like spins. The disordered magnetic structure at the surface of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts is responsible for the spin-glass-like behavior at low temperature. It should be mentioned that the nanorization can greatly affect the magnetization behavior of the magnetic materials in a variety of ways20,21, and in addition a small amount of iron oxide impurities, which even if cannot be detected by XRD, could also give rise to a weak ferromagnetism as well as exchange bias22,23. Therefore, the weak-ferromagnetic phenomenon in Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts needs further investigation.

Figure 4. Magnetic properties of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts.

(a), the M–H curves of the nanobelts at 300 K and 2 K. The top inset shows the temperature dependencies of ZFC and FC magnetizations at 50 Oe, and the bottom inset represents an enlarged view of the M–H curve at 300 K. (b–c), exchange bias effect in Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at 300 K (b) and 2 K (c), respectively. The M−H curves are measured in a field cooling model with the cooling fields HFC = +50 kOe (red solid square) and −50 kOe (blue open circle), respectively.

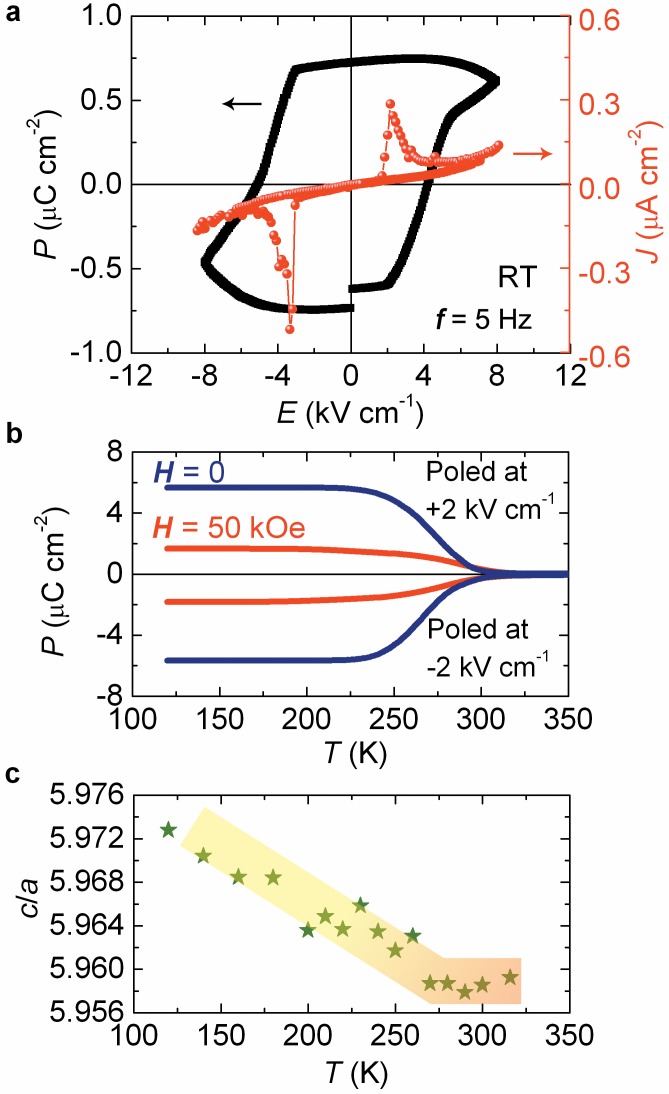

One of the most important results is that an evident ferroelectric behavior for the bulks made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts is obtained at room temperature as characterized by polarization hysteresis in Fig. 5a. A remanent polarization (P) of about 0.7 μC cm−2 and a coercive electric field (Ec) of about 4 kV cm−1 at room temperature can be clearly observed. The current switching peaks in the electric field (E) dependent charge current density (J) curve further confirm the ferroelectricity. As the structure of the perovskite block is close to that of BiFeO3, the ferroelectricity of the new compound might have a similar physical mechanism, that the “lone pairs” of the Bi ions in the perovskite blocks might give rise to an off-center distortion24,25. In Fig. 5b the temperature profiles of the electric polarization calculated by the pyroelectric current measurements show a broadening transition about from 320 K to 220 K with a steep around 270 K. The polarization can be switched with opposite poling electric fields, and the saturated polarization reaches 5.65 μC cm−2 at 120 K. Correspondingly, as shown in Fig. 5c, the temperature profile of teragonality c/a of the structure has a slope change at 270 K, and below 270 K the value of c/a increases evidently with the decreasing temperature, indicating ferroelectric distortion with an elongation of the c axis26. From Fig. 5c together with the SEM images of the cross-section of a Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ bulk shown in the Supplementary Fig. S6 where there are a certain amount of nanobelts with c-axes perpendicular to the pressure surface, we consider that the polarization behaviors of the nanobelts with c-axes perpendicular to the pressure surface will dominate polarization loop shape, and thus a near-square loop shape is obtained. Furthermore, it is very interesting that the ferroelectric polarization is distinctly suppressed under a magnetic field of 50 kOe (see Fig. 5b), indicating a possible strong magnetoelectric coupling in this system.

Figure 5. Ferroelectric properties of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts.

(a) P–E and J–E loops of the bulks made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at 300 K. (b) Temperature dependence of electric polarization in zero (blue line) and 50 kOe (red line) magnetic fields, and the value of the polarization was acquired by integrating the pyroelectric current. For the measurements the nanobelts were pressed into a bulk with a cuboid shape (2 × 2 × 0.5 mm3) under a pressure of 20 MPa at room temperature. (c) Temperature dependent c/a measurements for the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts, the yellow wide line is guide to eyes.

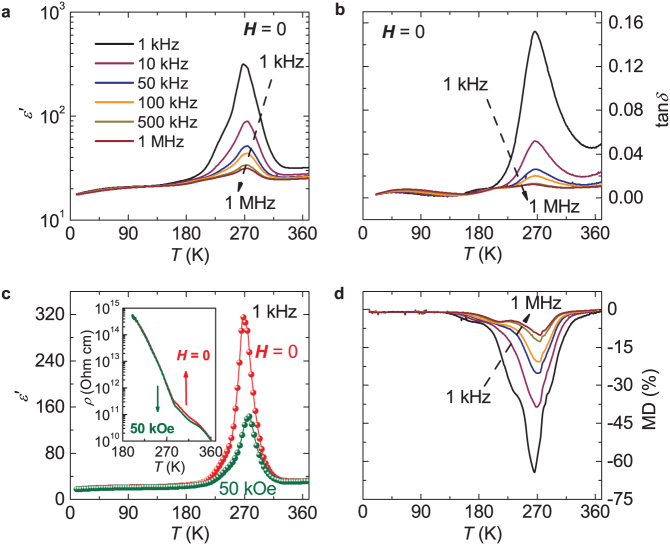

Figures 6a–b show the temperature dependencies of dielectric constant (ε′) and dielectric loss (tanδ) of the bulks made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts, respectively. The most remarkable feature is that the peak position near 270 K in each ε′–T curves is frequency independent, but the peak height ε′(270 K) decrease sharply with the increasing frequencies. It is known that a ferroelectric phase transition can make the dielectric constant divergent, so the peaks of the ε′–T curves may be further evidence for the ferroelectric transition of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts. M. Dawber et al. have reported that in their PbTiO3–SrTiO3 superlattice system the ferroelectric transition temperature decreases with decreasing FE layer volume fraction, and the Curie point of PbTiO3–SrTiO3 superlattice can be tuned from 1000 K to 300 K3. Suppose the ferroelectricity of the nanobelts originates from the BiFeO3-like perovskite layers, the insertion of the rock salt [Bi2O2]2+ layers may tune the ferroelectric Curie temperature to near room temperature, and make the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts be a high k-dielectric capacitor material with the operating temperature near room temperature, and keep the dielectric loss to be also quite low (see Fig. 6b). On the other hand, the K ions in the crystal lattices may also affect the ferroelectric Curie point as well as the polarization. Similar to the P–T curves (see Fig. 5b), the peaks of the ε′–T curves (see Fig. 6a) are very broadening with a temperature range from 200 K to 320 K, which may be due to the heterogeneity of the local structure of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts. When a magnetic field of 50 kOe is applied as shown in Fig. 6c, the dielectric hump is greatly suppressed but the peak temperature remains almost unchanged, revealing a magnetic manipulation of dielectric properties around the ferroelectric transition region. Fig. 6d shows the temperature dependence of the magnetodieletric effect (MD) which is defined as

It is notable that the MD coefficient is about −20% at 300 K and −64% at 270 K for the frequency of 1 kHz, which is at least two orders of magnitude higher than those of BiFeO3 ceramics27. While for the temperature region below 100 K, the MD coefficient is almost frequency independent and only about −1%. The temperature dependence of dc resistivity ρ of the samples at zero magnetic field and 50 kOe is shown in the inset of the Fig. 6c. Although the resistance of the nanobelts decreases slightly in the temperature range from 280 K to 330 K under a field of 50 kOe, the MD effect in the nanobelts cannot be originated by a well-known Maxwell–Wagner capacitor configuration with considering the magnetoresistance (MR) effect28,29. Firstly, for a negative MR dominated by the grains of the bulk samples in such a scenario, it will generally cause a positive MD effect30, but the MD coefficient shown in Fig. 6d is always negative in our case. Secondly, in spite of a MR related to spin-polarized tunneling across grain boundaries or interfaces may induce a negative MD coefficient, the dielectric loss should increase with increasing magnetic fields28. On the contrary, the dielectric loss of the nanobelts is actually reduced under a magnetic field, see Supplementary Fig. S7. Moreover, the MD effect of the nanobelts exists for the whole temperature range measured as described in Fig. 6d, while the MR only occurs within the temperature range from 280 K to 330 K, further confirming that the magnetocapacitance observed cannot be explained in terms of the MR of the samples. Therefore, we attribute the MD phenomenon in Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts to a strong magnetoelectric coupling effect, and the external magnetic field has an inhibitory effect on the ferroelectricity. Unfortunately, the coupling mechanism is not clear to date. As there is no obvious magnetic transition in the nanobelts near 270 K, the spin helix scenario could be ruled out6,31,32,33,34. The result also suggests that magnetic fields can suppress both the ferroelectric and dielectric behaviors mainly near the ferroelectric transition temperature, and one can conclude that besides “lone pairs” of the Bi ions in the perovskite blocks, the magnetoelectric coupling in the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts may have an inherent connection with the ferroelectric origin. Furthermore, K ions might also have effect on the multiferroic, but the role is not very clear. Therefore, a deep theoretical investigation is needed to reveal the origin of the multiferroicity as well as the magnetoelectric coupling effect in this new found compound.

Figure 6. Magnetocapacitance effect in Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts.

(a–b) Temperature dependence of dielectric constant ε′ (a), and dielectric loss tanδ (b) of the bulks made of the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts at 1 kHz, 10 kHz, 50 kHz, 100 kHz, 500 kHz and 1 MHz measured in zero magnetic field. (c) Temperature dependence of ε′ at 1 kHz under zero (red points) and 50 kOe (olive points) magnetic fields, respectively. The inset of (c) shows the temperature profiles of dc resistivity ρ at zero (red line) and 50 kOe (olive line), respectively. (d) The corresponding temperature dependence of the magnetocapacitance effect of the samples.

Discussion

Indeed, the regular stacking of the BiFeO3-like perovskite layers and the rock salt [Bi2O2]2+ layers makes the Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts have a natural ME–DE alternation as expected, and both the magnetism and ferroelectricity of the nanobelts coexisit even at room temperature despite both the magnetic ground state and the origin of the ferroelectricity need further investigations. In addition, both the high-TC superconductivity and multiferroic found in the Bi2212-like isostructural compounds with different characteristic perovskite layers demonstrate that there exist rich physical connotations in such a system. Therefore, our synthetic route may also open a window for seeking more isostructural compounds with novel features and excellent performance.

In summary, the single crystal Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts were successfully grown by using a hydrothermal method via replacing all the Sr and Ca ions by Bi and K ions and all the Cu ions by Fe ions based on the Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ structure. The nanobelts have a natural ME–DE layers alternating arrangement along the c axis of the crystal, and the room-temperature multiferroic is achieved. These observations may be advantageous for the finding of new type magnetoelectric materials as well as tunable logic nano-device applications.

Methods

The Bi4.2K0.8Fe2O9+δ nanobelts with ME–DE type layered structure were prepared by a surfactant-free hydrothermal synthesis method. All chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification. In a typical procedure, an aqueous solution of 5 mL was first prepared by dissolving 0.4 mmol Bi(NO3)3·5H2O, 0.19 mmol Fe(NO3)3·9H2O, and 1 mL nitric acid in distilled water. The mixture was dropped into KOH solution (15 mL) as slowly as possible under magnetic stirring and the final concentration of KOH was 12 M. The suspension solution was transferred to a stainless steel Teflon-lined autoclave of 25 mL capacity. The reaction was performed by heating the autoclave at 190°C for 90 min with a heating rate of 2°C min−1. After it was cooled to ambient temperature naturally, the final products were collected by centrifugation, washed several times with distilled water and ethanol, and dried at 120°C for 6 h in air before further characterizations.

The structure of the synthesized nanobelts was recorded with an X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. The microscopic structure and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) analysis were examined by scanning electron microscopy and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy.

The magnetic properties were determined with a commercial magnetometer. The P–E hysteresis loops were measured at 5 Hz using a standard ferroelectric tester. For the electric measurement, the nanobelts were fully pulverized in an agate mortar using absolute alcohol as the grinding aid, then the obtained powder were pelletized to a bulk with a tetragonal shape (2 × 2 × 0.5 mm3, the density is 5.4 mg mm−3 which is about 70% of the theoretical value) in a stainless steel mold at room temperature under a vertical pressure of 20 MPa and a pressure-holding time of 6 hours, then silver electrodes were deposited onto the opposite 2 × 2 mm2 pressure surfaces. The dielectric constant was measured using a LCR (inductance–capacitance–resistance) meter. The temperature dependence of electric polarization was obtained by measurements of pyroelectric current. The sample is cooled down from 400K to a given low temperature in an electric field of 2 kV cm−1, then the poling electric field was removed and the samples were short-circuited for 4 hours. Then, the samples were heated at a constant rate (3 K min−1), and the pyroelectric currents were measured. The pyroelectric currents and the dc resistivity of the samples were determined with an electrometer.

Author Contributions

X.G.L. conceived the project and designed the experiments. S.N.D. performed the syntheses and experimental measurements. Y.J.S., S.N.D. and J.Q.L. performed the characterizations and structural analysis. Y.P.Y. and Y.K.L. contributed to the ferroelectric measurements. S.N.D. and X.G.L. wrote the paper. All authors contributed through scientific discussions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The work at USTC was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the National Basic Research Program of China (Contract Nos. 2012CB922003, 2011CBA00102 and 2009CB929502). The work at IOP was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Contract No. 2012CB821404).

References

- Bousquet E., Dawber M., Stucki N., Lichtensteiger C., Hermet P., Gariglio S., Triscone J. M. & Ghosez P. Improper ferroelectricity in perovskite oxide artificial superlattices. Nature 452, 732–734 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnders G. & Blank D. H. A. Materials science - Build your own superlattice. Nature 433, 369–370 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawber M., Stucki N., Lichtensteiger C., Gariglio S., Ghosez P. & Triscone J. M. Tailoring the properties of artificially layered ferroelectric superlattices. Adv. Mater. 19, 4153–4159 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Das R. R., Yuzyuk Y. I., Bhattacharya P., Gupta V. & Katiyar R. S. Folded acoustic phonons and soft mode dynamics in BaTiO3/SrTiO3 superlattices. Phys. Rev. B 69, 132302 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Ranjith R., Kundys B. & Prellier W. Periodicity dependence of the ferroelectric properties in BiFeO3/SrTiO3 multiferroic superlattices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 222904 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T., Goto T., Shintani H., Ishizaka K., Arima T. & Tokura Y. Magnetic control of ferroelectric polarization. Nature 426, 55–58 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. M., Li Z., Chen L. Q. & Nan C. W. High-density magnetoresistive random access memory operating at ultralow voltage at room temperature. Nature Communications 2, 553 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig M. Revival of the magnetoelectric effect. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 38, R123–R152 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S. J., Liu Y. T., Lee H. Y., Yu G. P. & Huang J. H. Growth of BiFeO3/SrTiO3 artificial superlattice structure by RF sputtering. J. Cryst. Growth 334, 90–95 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Dawber M., Rabe K. M. & Scott J. F. Physics of thin-film ferroelectric oxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1083 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Mao X. Y., Wang W., Chen X. B. & Lu Y. L. Multiferroic properties of layer-structured Bi5Fe0.5Co0.5Ti3O15 ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 082901 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Munzarova M. L. & Hoffmann R. Strong electronic consequences of intercalation in cuprate superconductors: The case of a trigonal planar AuI3 complex stabilized in the Bi2Sr2CaCu2Oy lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 5542–5549 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong S. W. & Mostovoy M. Multiferroics: a magnetic twist for ferroelectricity. Nat. Mater. 6, 13–20 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K. F., Liu J. M. & Ren Z. F. Multiferroicity: the coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 58, 321–448 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Le Page Y., McKinnon W. R., Tarascon J. M. & Barboux P. Origin of the incommensurate modulation of the 80-K superconductor Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8.21 derived from isostructural commensurate Bi10Sr15Fe10O46. Phys. Rev. B 40, 6810 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez O., Leligny H., Grebille D., Labbe P., Groult D. & Raveau B. X-ray investigation of the incommensurate modulated structure of Bi2+xSr3−xFe2O9+delta. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 7, 10003–10014 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Zeches R. J., Rossell M. D., Zhang J. X., Hatt A. J., He Q., Yang C. H., Kumar A., Wang C. H., Melville A., Adamo C., Sheng G., Chu Y. H., Ihlefeld J. F., Erni R., Ederer C., Gopalan V., Chen L. Q., Schlom D. G., Spaldin N. A., Martin L. W. & Ramesh R. A Strain-Driven Morphotropic Phase Boundary in BiFeO3. Science 326, 977–980 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. H., Luo Z. L., Huang C. W., Qi Y. J., Yang P., You L., Hu C. S., Wu T., Wang J. L., Gao C., Sritharan T. & Chen L. Low-Symmetry Monoclinic Phases and Polarization Rotation Path Mediated by Epitaxial Strain in Multiferroic BiFeO3 Thin Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 133–138 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Dong S. N., Yao Y. P., Hou Y., Liu Y. K., Tang Y. & Li X. G. Dynamic properties of spin cluster glass and the exchange bias effect in BiFeO3 nanocrystals. Nanotechnology 22, 385701 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T. J., Papaefthymiou G. C., Viescas A. J., Moodenbaugh A. R. & Wong S. S. Size-dependent magnetic properties of single-crystalline multiferroic BiFeO3 nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 7, 766–772 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. H., Ding J. F., Zhang G. Q., Hou Y., Yao Y. P. & Li X. G. Size-dependent exchange bias in La0.25Ca0.75MnO3 nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. B 78, 224408 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Lin Y. H., Zhang B. P., Wang Y. & Nan C. W. Controlled Fabrication of BiFeO3 Uniform Microcrystals and Their Magnetic and Photocatalytic Behaviors. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 2903–2908 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Shendruk T. N., Desautels R. D., Southern B. W. & van Lierop J. The effect of surface spin disorder on the magnetism of gamma-Fe2O3 nanoparticle dispersions. Nanotechnology 18, 455704 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Seshadri R. & Hill N. A. Visualizing the role of Bi 6s "Lone pairs" in the off-center distortion in ferromagnetic BiMnO3. Chem. Mater. 13, 2892–2899 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Neaton J. B., Zheng H., Nagarajan V., Ogale S. B., Liu B., Viehland D., Vaithyanathan V., Schlom D. G., Waghmare U. V., Spaldin N. A., Rabe K. M., Wuttig M. & Ramesh R. Epitaxial BiFeO3 multiferroic thin film heterostructures. Science 299, 1719–1722 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai H., Fujioka J., Fukuda T., Okuyama D., Hashizume D., Kagawa F., Nakao H., Murakami Y., Arima T., Baron A. Q. R., Taguchi Y. & Tokura Y. Displacement-Type Ferroelectricity with Off-Center Magnetic Ions in Perovskite Sr1−xBaxMnO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 137601 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamba S., Nuzhnyy D., Savinov M., Šebek J., Petzelt J., Prokleška J., Haumont R. & Kreisel J. Infrared and terahertz studies of polar phonons and magnetodielectric effect in multiferroic BiFeO3 ceramics. Phys. Rev. B 75, 024403 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Catalan G. Magnetocapacitance without magnetoelectric coupling. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 102902 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Catalan G. & Scott J. F. Magnetoelectrics - Is CdCr2S4 a multiferroic relaxor? Nature 448, E4–E5 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S. N., Hou Y., Yao Y. P., Yin Y. W., Ding D., Yu Q. X. & Li X. G. Magnetodielectric Effect and Tunable Dielectric Properties of LaMn1−xFexO3. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 93, 3814–3818 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga Y., Furukawa N., Sakai H., Taguchi Y., Arima T. H. & Tokura Y. Composite domain walls in a multiferroic perovskite ferrite. Nat. Mater. 8, 558–562 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokura Y. & Seki S. Multiferroics with Spiral Spin Orders. Adv. Mater. 22, 1554–1565 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa Y., Hiraoka Y., Honda T., Ishikura T., Nakamura H. & Kimura T. Low-field magnetoelectric effect at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 9, 797–802 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun S. H., Chai Y. S., Jeon B.-G., Kim H. J., Oh Y. S., Kim I., Kim H., Jeon B. J., Haam S. Y., Park J.-Y., Lee S. H., Chung J.-H., Park J.-H. & Kim K. H. Electric Field Control of Nonvolatile Four-State Magnetization at Room Temperature. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 177201 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information