Abstract

Introduction

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a novel and effective surgical intervention for refractory Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Methods

We review the current literature to identify the clinical correlates associated with STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania in PD patients.

Results

Ventromedial electrode placement has been most consistently implicated in the induction of STN DBS-induced mania. There is some evidence of symptom amelioration when electrode placement is switched to a more dorsolateral contact. Additional clinical correlates may include unipolar stimulation, higher voltage (>3 V), male patients and/or early onset PD.

Conclusion

STN DBS-induced psychiatric adverse events emphasize the need for comprehensive psychiatric presurgical evaluation and follow-up in PD patients. Animal studies and prospective clinical research, combined with advanced neuroimaging techniques, are needed to identify clinical correlates and underlying neurobiological mechanism(s) of STN DBS-induced mania. Such working models would serve to further our understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of mania and contribute valuable new insight towards development of future DBS mood stabilization therapies.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, mania, subthalamic nucleus (STN), deep brain stimulation (DBS)

INTRODUCTION

Parkinson’s disease (PD) affects as many as 1 million people in the United States alone, with approximately 40,000 Americans diagnosed with the disease annually. The hallmark neuropathology of the disease is loss of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons and intracytoplasmic Lewy bodies in the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus (1). The disease has a high degree of morbidity and is associated with significant use of nursing home services, antidepressant and antipsychotic treatment, and overall reduced survival time as compared to people without PD (2).

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an FDA-approved surgical treatment for management of advanced PD. In comparison to medication management, DBS significantly improves motor symptoms and quality of life (3–5). Subthalamic nucleus (STN) is used more commonly as the anatomic target for DBS, although, a 24-month randomized blinded trial comparing STN and globus pallidus internus (GPi) stimulation showed similar motor function improvement (6). However, there were several secondary outcomes suggesting differential impact on mood based on anatomic targets. At study endpoint, the STN group, in comparison to GPi, had statistically significant higher score (p=0.02) on the Beck Depression Inventory (STN =12.5 ± 8.5 vs. GPi = 9.8± 7.3). Subscales quantifying mood and emotional well being on PD rating scales including United Parkinson’s disease rating scale (UPDRS) and Parkinson’s disease questionnaire (PDQ-39) showed similar differences STN vs GPi (6). In contrast, a recent 7-month double-blind randomized study comparing cognition and mood as primary outcome in STN and GPi groups (COMPARE Trial) reported no significant differences in mood and cognition outcomes between the two groups (7) in the optimal stimulation condition.

In a review of 82 studies that included almost 1400 PD patients, STN DBS has been associated with new onset psychiatric adverse events including depression (8%), hypomania/mania (4%), anxiety (2%), and attempted suicide (0.4%) (8); while the sample is large, definitive conclusions are limited given the lack of standardized assessment of psychiatric diagnosis and/or adverse events. Given the baseline estimate of PD comorbidity with psychiatric disorders (9) including depression (25%), psychotic syndromes (12.7%), sleep disturbances (49%), and anxiety (20 %) plus the additional risk associated with STN DBS, there is great need to understand the clinical correlates associated with STN DBS-induced psychiatric adverse events (PAE’s). Given a recent report of voltage-dependent mania associated with STN DBS in a PD patient (10), this literature review is focused on identifying underlying neurobiological mechanisms and clinical correlates of STN DBS-induced mania.

METHODS

A structured Medline (Pubmed) search was performed through December 2010 with key words including: subthalamic nucleus (STN), Parkinson’s disease (PD), deep brain stimulation (DBS), mania, hypomania, and mood elevation. Seven published case reports (11–15), two case series (16,17) and one retrospective cohort study (18) with well-documented demographics, stimulation parameters, and details of psychiatric symptoms to confirm STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania were identified (total n=17 patients). Levodopa equivalent daily dose (LEDD) was computed based on the following formula: total l-dopa=(regular L-dopa dose × 1) + (L-dopa controlled release × 0.75) + (pramipexole dose × 67) + (ropinirole dose × 16.67) + (pergolide dose × 100) + (bromocriptine dose × 10), + [(L-dopa + L-dopa controlled release × 0.75) × 0.25 if taking tolcapone (regardless of tolcapone dose)] (19).

RESULTS

The clinical correlates associated with STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania can be subcategorized into electrode placement, stimulation parameters (unipolar vs. bipolar stimulation and voltage), and neurosurgical (i.e. lesioning effect), neurological (age at onset of PD, LEDD change), and demographic factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Correlates of STN DBS-induced Hypomania/ Mania

| Author | Age(y)/ Sex |

PD illness |

Psychiatric History |

LEDD † Change |

Left (Lt) EC/Voltage |

Right (Rt) EC/Voltage |

Mania ‡ assessment |

Factors associated with manic resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kulisevsky et al, n= 3 |

Mean= 50/M |

Mean 9 yrs |

None | 43% ▼ | 0(−), 1(+); 2 V |

0(−), 1(+); 2V |

Mania d=1 (mean YMRS score - 35) |

Stimulation of dorsal contacts in all three cases |

| Mandat et al, n=2 |

Mean= 59/M |

Mean 16 yrs |

None | 75% ▼ | n=1: 5(−); 1.8V monopolar; n=2: 5(−) 6(−); 3 V |

n=1: 0(−); 2V; n=2:1(−); 1.7 V |

Hypomania, mean d=45 |

n=1: Rt 1.8V, 1(−), 2(+) Lt. 5 (−) 6(+);bipolar n=2: Rt 2 V, 2 (−), 3 (−); Lt. 2 V, 6(−), 7(−) |

| Romito et al, n=2 |

Mean 47/M |

Mean 13 yrs |

n=1: Major depression n=2: none |

100 % ▼ | 0 | 1 | Mania, n=1: d*=2 n=2: d=3 (DSM-IV criteria) |

Spontaneous resolution in 3–6 months |

| Raucher- Chene et al, n=1 |

60/M | 8 yrs | Major depressive episode at age 56 |

NS | 2; 3 V | 5; 3V | Hypomania, d=4 | Shifting the electrodes to contacts 3 (Lt) and 6 (Rt); ineffective Valproate trial |

| Herzog, et al, n=1 |

65/F | 14 yrs | Family History of BPAD* |

26% ▼ | NS; 2.2 V, monopolar |

NS; 2.6 V | Mania, d=7 (BRMAS score- Pre-op: 6/44, Post-op:25/44) |

Clozapine and Carbamazepine |

| Funkiewei z et al, n=1 |

43/M | 17 yrs | Moderate depression |

100% ▼ | NS | NS | Hypomania, d=90 | NS |

| Tsai et al, n=1 |

50/M | 10 yrs | Major depression | 33% ▼ | 1(−), 3.4 V, monopolar |

NS | Mania, d= 90 | Lt Bipolar mode (contact 1- and 3+), decreased voltage (3.4 to> 3V); Quetiapine |

| Coenen et al, n=1 |

66/M | NS | Pramipexole induced sexual disinhibition |

NS | 5(−); 2 V; monopolar |

2; 2 V; monopolar |

Hypomania, d=10 | Bipolar mode, lower amplitude and more superficial contact settings (ECs 3 & 6) |

| Ulla et al, n=5 |

Mean= 62 (2F,3M ) |

8.8 yrs | None | 63% ▼ | 4; 3.09 V | 0,1; 3.09 V | Mania, d=1 (BRMAS mean score= 7.8) |

Manic symptoms resolved with euthymic contacts- (Lt): 5,7 & (Rt): 1,2,3 |

LEDD - Levodopa equivalent daily dose

YMRS - Young Mania Rating Scale

d - days to onset of hypomania/mania after DBS implant

d* - prior to turning stimulator on

BRMAS - Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale

NS - Not specified

DSM-IV - Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, IV edition;

BPAD* - Bipolar Affective Disorder

Fourteen out of seventeen (82%) patients developed STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania with ventromedial STN electrode placement (12–18). This pattern was reproducible (i.e. induction of manic symptoms with ventral stimulation and resolution of manic symptoms with switch to dorsolateral simulation) in five patients (17). Where reported, manic symptoms appeared to resolve in 12/14 (86%) patients after switching from ventromedial to dorsolateral STN; this occurred with an electrode configuration switch alone in 9/12 (75%) patients or in combination with changes in stimulation parameters (i.e. voltage and stimulation mode) in 3/12 (25%) patients.

In two case reports (13, 18), both voltage >3V and monopolar stimulation mode were associated with STN DBS-induced mania. Monopolar stimulation produces a current that runs in multiple parallel paths. This kind of stimulation may influence a larger volume of tissue especially when the current density is relatively high. Bipolar stimulation produces a more concentrated electric field around the electrode pair (20). Both increased voltage and unipolar stimulation can potentially result in enhanced current spread throughout the local tissue (relative to lower voltage or bipolar stimulation) and thus would be expected to influence a greater proportion of STN and nearby cells (21). Lowering voltage along with switching to bipolar stimulation mode has been associated with manic symptom resolution (13, 18).

The clinical correlates associated with STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania in the immediate and early postoperative period may include localized edema, a partial lesioning effect due to STN DBS implant (11), as well as a possible add – on effect of STN DBS to the levodopa treatment (5,18,22). The mean duration of onset of hypomania/mania in 17 patients was found to be 17.8 ± 30.6 days.

Amongst the demographic and neurological correlates, 14/17 (82%) of patients with STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania were males (n=14, mean age= 55.6 ±10.6 years) with relatively early onset of PD (n=13, mean age at PD onset- 43.6 ±11.5 years) as compared to 3/17 (17%) female patients (n=3, mean age = 58.6 ± 6 years, mean age at PD onset= 48.3 ±2.5 years). A history of major depression or dopamine induced mood disorder has been reported in 4/17 (23%) cases.

DISCUSSION

Despite the increasing use of DBS as a therapeutic tool for PD, the precise mechanism of action of DBS is currently debated. Since the therapeutic effects of DBS are similar to those of a lesion, DBS has been thought to silence neurons at the site of stimulation. Reviewed extensively elsewhere (23,24) hypotheses concerning the mechanism of action of DBS have focused on a state of depolarization blockade at the stimulation site. This DBS-mediated neural network disruption has been hypothesized to result from preferential activation of GABAergic inhibitory neurons or high frequency stimulation-mediated jamming of normal neuronal communication (25–28). However, there is also evidence to suggest that DBS can elicit neurotransmitter release distal to the site of stimulation (29–31) and/or effect more enduring plasticity-mediated changes in network function (32).

STN DBS mechanism of action: Pre-clinical models

Bilateral STN DBS typically reduces the need for L-DOPA treatments and recovers striatal dopamine receptor function indicating that dopamine levels have increased (33,34). This suggests that clinically effective STN DBS mediates dopamine neurotransmission. In support of this, striatal dopamine release during STN DBS has been demonstrated in both intact and dopamine depleted pre-clinical animal models (31, 35–39). Furthermore, STN DBS-evoked dopamine efflux has recently been reported in a large animal (pig) model that faithfully replicates the human DBS neurosurgical procedure and stimulation paradigm (39). In this study, DBS-mediated striatal dopamine release was observed to be voltage dependent in that while maintaining constant frequency (120 Hz), increases in the voltage intensity from 3 to 7 V resulted in a progressive increase in striatal dopamine release. Animal studies have also suggested that dopamine synthesis may be upregulated by DBS (37,40).

Extrapolation of results from pre-clinical animal models directly to DBS-mediated effects in PD patients, however, must be done with some caution. Differences in the type of electrodes utilized, as well as the scale and anatomy of the rodent brain, somewhat limit translation of the findings. In particular, specific parameters applied to the DBS electrode and the precise location of active leads within the brain can profoundly influence the biological impact of high frequency stimulation on neuronal activity and neurotransmitter efflux (41,42).

Given the potential for dopamine dysregulation to contribute towards behavioral expression of mania in PD (43,44), observations of up-regulated dopamine receptor function in STN DBS patients, and preclinical data demonstrating STN DBS-elicited dopamine release in motor and limbic basal ganglia circuits (29,31), the potential for regional STN DBS to contribute to the occurrence of manic symptoms needs to be explored more fully. Towards this end, a recent preclinical primate study has demonstrated that reversible, regional dysfunction of the STN selectively induces movement disorders and radical changes in behavior in healthy animals. In particular, the induction of hyperactivity reliably occurred with inhibition of the anteromedial region of the STN (45).

STN DBS mechanism of action: Clinical models

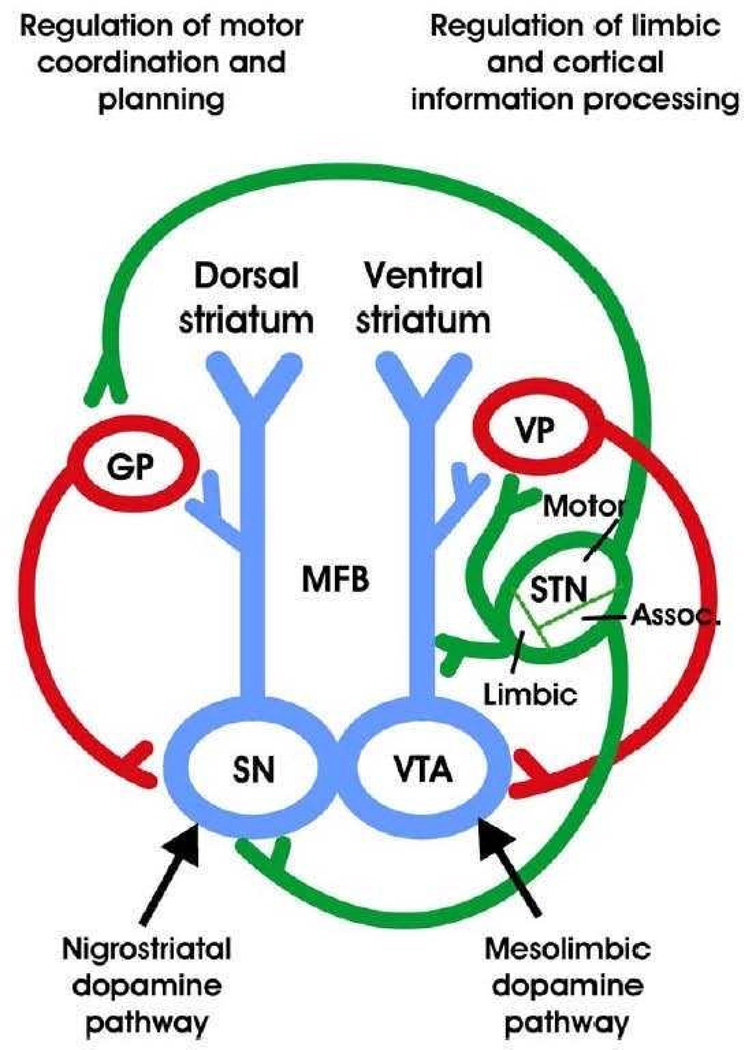

The subthalamic nucleus (STN) is subdivided into three territories: dorsolateral motor territory; ventromedial cognitive territory; and medial limbic territory. Each provides output to different target nuclei to regulate motor, cognitive and emotional functions. STN regulation of nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine activity helps to coordinate these functions and is likely implicated in both the therapeutic benefits and unwanted PAE’s associated with STN DBS.

Therapeutic effects of STN DBS in PD are optimized when the electrode is placed in the dorsolateral motor territory. Excitatory glutamatergic efferents project from the dorsolateral motor territory of the STN to the globus pallidus (GP). The GP in turn sends an inhibitory GABAergic projection to the dopamine cell bodies of the substantia nigra (SN). The SN is also innervated by an excitatory glutamatergic afferent from the ventromedial associative territory of the STN as depicted in Figure 1 (46). Thus, DBS activation of these projections could increase dopamine cell activity in the SN and dopamine release in the dorsal striatum to mediate motor function. Conversely, when the DBS electrode is positioned in the limbic territory, excitatory glutamatergic projections to dopaminergic axons of the median forebrain bundle (MFB) may be activated (15). The axons activated in this instance arise out of dopamine cell bodies in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and project to the ventral striatum to influence the processing of limbic and cortical information. A glutamatergic projection is also sent from the limbic STN to the ventral pallidum (VP), which in turn sends an inhibitory GABAergic projection to the VTA, activation of which would inhibit dopamine cells.

Figure 1.

The subthalamic nucleus (STN) is subdivided into 3 territories: dorsolateral motor territory; ventromedial associative territory; and medial limbic territory. Each provides output to different target nuclei to regulate motor, cognitive and emotional functions. STN regulation of nigrostriatal and mesolimbic dopamine activity plays an important role in coordination of these functions, and is likely relevant for management of both the therapeutic benefits and unwanted side effects elicited by STN-DBS. Blue = dopamine; green = glutamate; red = GABA.

Given that dysregulation of mesolimbic dopamine is implicated in the expression of manic symptomatology, further investigation of the effects of STN DBS on mesolimbic dopamine is much needed, as is determination of its role in STN DBS-induced hypomania.

A role for the STN in regulation of emotional responses and behavior is becoming clearer and several neuroimaging studies have reported DBS-induced specific changes at the level of cortical and subcortical associative and limbic regions (47–49). Such a potent influence on associative, limbic, and motor functions has not been observed with other targets like the GPi (50–53) or the thalamus (54,55). In addition, recent controlled data have suggested that PD patient status post DBS had differential emotional responses based on dorsal or ventral contact STN stimulation (56). Emotional reactivity from 20 PD patients with bilateral STN DBS was quantified by assessing emotional reaction to three different movie clips of different valence (neutral, sad, and amusing); ventral stimulation was associated with significantly increased ratings of positive affect as compared to dorsal stimulation. Not surprisingly, STN stimulation, particularly when contacts are located ventromedially to the intended motor territory, may result in adverse cognitive and neuropsychiatric outcomes including transient confusion, apathy, reduced verbal fluency, impaired attention, working memory, response inhibition, depression, anxiety, hypomania, hypersexuality, hallucinations, psychosis, and even suicide (46).

STN DBS-induced mania: underlying neurobiology and clinical correlates

Application of DBS to the ventromedial STN, particularly with high voltages and/or unipolar stimulation mode, can potentially stimulate adjacent neural structures including the substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area and lateral hypothalamus (14). STN DBS has also been associated with potential stimulation of more formal neural circuits including orbito-frontal basal ganglia (12), midbrain-orbitofrontal brain regions, anterior cingulate striato-pallido-thalamo-cortical circuits, or fibers from the ventral tegmentum area to the limbic striatum, causing symptoms typical of mania (57–59). Based on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), STN DBS-induced reversible acute hypomania might be elicited by inadvertent and unilateral co-activation of putative limbic STN tributaries to the medial forebrain bundle (MFB), a recently identified pathway connecting the medial STN to reward circuitry (13).

A recent study focusing on contact-dependent reproducible hypomania in five PD patients demonstrates the role of subcortical structures, specifically substantia nigra, in the genesis of STN DBS-induced hypomania. Three dimensional anatomical reconstruction with multimodal imaging (preoperative stereotactic MRI, postoperative CT scan, O15 PET scan) of ‘euthymic’ and ‘manic’ contacts revealed that 9/10 ‘manic’ contacts were located in ventral substantia nigra with right anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex activation(17).

The observation of bilateral globus pallidus DBS induced mania in a patient with no previous psychiatric history (60) suggests that there may be other stimulation sites outside of STN that have potential to cause this psychiatric adverse event. Due to the much less reported burden of PAE’s associated with GPi stimulation; it may be an intuitive target choice for DBS stimulation in patients at risk of developing DBS-induced PAE’s. However, this data is limited and higher rate of suicide in a 10-year meta-analysis has been reported with GPi stimulation (61).

The literature, reviewed to date, would suggest that STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania seems to be most consistently associated with ventromedial STN electrode placement. The reproducibility of mania with ventral stimulation, resolution of manic symptoms with dorsal stimulation in 86% of cases (a change which also shifts the stimulated site laterally given the typical DBS lead trajectory) and persisting manic symptoms despite significant reduction in LEDD further confirms this association. In terms of stimulation parameters, higher stimulation voltage (>3V) and/or unipolar stimulation mode have been associated with STN DBS-induced mania. The voltage-dependent nature of STN DBS-induced mania (10) replicates recently reported voltage dependent dopamine efflux in a large animal model of DBS (39).

Males and/or those with early onset PD may be at significant risk of developing treatment emergent adverse events to a number of PD treatment interventions. In a multi-centre study on suicide outcomes following STN DBS for Parkinson’s disease (62), younger age and early onset PD were significantly associated with STN DBS treatment emergent suicide attempts. Furthermore, in a cross sectional evaluation of patients evaluated in a Movement Disorders Clinic, men were more likely to develop dopamine agonist induced impulse controls disorders (63). These findings may suggest that males and/or early onset PD may represent the PD population to be at the most risk to develop dopamine agonist, whether medication or DBS induced, psychiatric adverse events such as mania and suicidality, whether medication or DBS induced.

Somewhat surprising, a past psychiatric history of depression or dopamine-induced mood disorder was only present in 4/17 (23%) of reported cases. It may be possible that STN DBS may have unmasked symptoms of pre-existing psychiatric illness that were not identified in baseline assessment (64). Patients with preoperative cognitive deficits and affective disorders seem to be at risk of behavioral problems after STN DBS surgery (65, 66). A recent small study of 14 PD patients undergoing STN DBS suggested that baseline motor impairment was associated with post-surgical hypomania symptoms (67) as it has already been suggested that sudden improvement in motor function after DBS surgery may have a profound effect on mood (68).

LIMITATIONS

We acknowledge that the psychiatric side effects after STN DBS surgery are published mostly in case report format; their frequency might be overestimated (22,69,70). But it might equally well be the case that frequency of such side effects is underestimated as these side effects are not subjected to systematic assessment. The precise mechanism(s) of action of STN DBS-induced hypomania/mania is currently not well understood. Our findings/proposed mechanisms may still be preliminary and speculative, and this needs further systematic research.

CONCLUSION

STN DBS-induced mania and other adverse events emphasize the need for comprehensive pre-surgery psychiatric evaluation and close follow-up after implantation. Given the significant psychiatric morbidity and mortality associated with STN DBS surgery in PD patients, there is need for pre-clinical animal studies and prospective cohort/ longitudinal studies, combined with advanced neuroimaging techniques, to specifically establish psychiatric, neurological and neurosurgical correlates and elucidate the neurobiological mechanism(s) associated with STN DBS-induced mania. Such working models would serve to further our understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of mania and contribute valuable new insight towards development of future DBS mood stabilization therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Ms. Cindy Stoppel for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES

Mark A. Frye M.D. 2010

Grant Support

Pfizer, National Alliance for Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Mayo Foundation

Consultant

Dainippon Sumittomo Pharma, Merck, Sepracor

CME supported Activity

Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis

Speakers’ Bureau

NONE

Financial Interest / Stock ownership / Royalities

NONE

Dr. Kendall H. Lee 2010

Patents pending concerning DBS technology and has received industry support from St. Jude Neuromodulation division.

This work was supported by NIH (K08 NS 52232 award) and Mayo Foundation (2008–2010 Research Early Career Development Award for Clinician Scientists) to KHL.

Julie A. Fields, PhD 2010

Consultant

Medtronic, Inc.

Footnotes

Presented in part at American Neuropsychiatric Association Meeting Tampa, Florida, March 18th 2010. SJT supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lauterbach EC. The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson’s disease. Minerva Medica. 2005;96:155–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parashos SA, Maraganore DM, O’Brien PC, et al. Medical services utilization and prognosis in Parkinson disease: a population-based study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2002;77:918–925. doi: 10.4065/77.9.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weaver FMP, Follett KMDP, Stern MMD, et al. Bilateral Deep Brain Stimulation vs Best Medical Therapy for Patients With Advanced Parkinson Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2009;301:63–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witt K, Daniels C, Reiff J, et al. Neuropsychological and psychiatric changes after deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, multicentre study. The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7:605–614. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70114-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krack P, Batir A, Van Blercom N, et al. Five-year follow-up of bilateral stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:1925–1934. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Follett KA, Weaver FM, Stern M, et al. Pallidal versus Subthalamic Deep-Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2077–2091. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907083. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okun MS, Fernandez HH, Wu SS, et al. Cognition and mood in Parkinson’s disease in subthalamic nucleus versus globus pallidus interna deep brain stimulation: the COMPARE trial. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(5):586–595. doi: 10.1002/ana.21596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temel Y, Kessels A, Tan S, et al. Behavioural changes after bilateral subthalamic stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2006;12:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riedel O, Klotsche J, Spottke A, et al. Frequency of dementia, depression, and other neuropsychiatric symptoms in 1,449 outpatients with Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5465-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra A, Tye S, Kendall L, et al. Voltage-Dependent Mania Status-Post Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson’s disease; A case report. Biological Psychiatry. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.035. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romito LM, Raja M, Daniele A, et al. Transient mania with hypersexuality after surgery for high frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2002;17:1371–1374. doi: 10.1002/mds.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herzog J, Reiff J, Krack P, et al. Manic episode with psychotic symptoms induced by subthalamic nucleus stimulation in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2003;18:1382–1384. doi: 10.1002/mds.10530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coenen VA, Honey CR, Hurwitz T, et al. Medial forebrain bundle stimulation as a pathophysiological mechanism for hypomania in subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:1106–1114. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000345631.54446.06. discussion 1114–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandat TS, Hurwitz T, Honey CR, et al. Hypomania as an adverse effect of subthalamic nucleus stimulation: report of two cases. Acta Neurochirurgica. 2006;148:895–897. doi: 10.1007/s00701-006-0795-4. discussion 898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raucher-Chene D, Charrel C-L, de Maindreville AD, et al. Manic episode with psychotic symptoms in a patient with Parkinson’s disease treated by subthalamic nucleus stimulation: improvement on switching the target. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2008;273:116–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kulisevsky J, Berthier ML, Gironell A, et al. Mania following deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2002;59:1421–1424. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.9.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ulla M, Thobois S, Llorca PM, et al. Contact dependent reproducible hypomania induced by deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: clinical, anatomical and functional imaging study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010 Nov 3; doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.199323. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai S-TMD, Lin S-HMD, Lin S-ZMDPD, et al. Neuropsychological effects after chronic subthalamic stimulation and topography of the nucleus in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:E1024–E1030. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000303198.95296.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hobson DEMDF, Lang AEMDF, Martin WRWMDF, et al. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Sudden-Onset Sleep in Parkinson Disease: A Survey by the Canadian Movement Disorders Group. JAMA. 2002;287:455–463. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.4.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temel Y, Visser-Vandewalle V, van der Wolf M, et al. Monopolar versus bipolar high frequency stimulation in the rat subthalamic nucleus: differences in histological damage. Neuroscience Letters. 2004;367:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McIntyre CC, Mori S, Sherman DL, et al. Electric field and stimulating influence generated by deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2004;115:589–595. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funkiewiez A, Ardouin C, Krack P, et al. Acute psychotropic effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation and levodopa in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2003;18:524–530. doi: 10.1002/mds.10441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopell BH, Greenberg BD. Anatomy and physiology of the basal ganglia: implications for DBS in psychiatry. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:408–422. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tye SJ, Frye MA, Lee KH. Disrupting disordered neurocircuitry: treating refractory psychiatric illness with neuromodulation. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2009;84:522–532. doi: 10.4065/84.6.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benazzouz A, Piallat B, Pollak P, et al. Responses of substantia nigra pars reticulata and globus pallidus complex to high frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in rats: electrophysiological data. Neuroscience Letters. 1995;189:77–80. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia L, D’Alessandro G, Bioulac B, et al. High-frequency stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: more or less? Trends in Neurosciences. 2005;28:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lozano AM, Dostrovsky J, Chen R, et al. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: disrupting the disruption. Lancet Neurology. 2002;1:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magarinos-Ascone C, Pazo JH, Macadar O, et al. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus silences subthalamic neurons: a possible cellular mechanism in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroscience. 2002;115:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee KH, Blaha CD, Harris BT, et al. Dopamine efflux in the rat striatum evoked by electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus: potential mechanism of action in Parkinson’s disease. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;23:1005–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCracken CB, Grace AA. High-frequency deep brain stimulation of the nucleus accumbens region suppresses neuronal activity and selectively modulates afferent drive in rat orbitofrontal cortex in vivo. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:12601–12610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3750-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winter C, Lemke C, Sohr R, et al. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus modulates neurotransmission in limbic brain regions of the rat. Experimental Brain Research. 2008;185:497–507. doi: 10.1007/s00221-007-1171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang-Hong L, Jin-Yan W, Ge G, Jing-Yu C, et al. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus restores neural and behavioral functions during reaction time task in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2009;9999 doi: 10.1002/jnr.22313. NA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blahak C, Bazner H, Capelle H-H, et al. Rapid response of parkinsonian tremor to STN-DBS changes: direct modulation of oscillatory basal ganglia activity? Movement Disorders. 2009;24:1221–1225. doi: 10.1002/mds.22536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hesse S, Strecker K, Winkler D, et al. Effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation on striatal dopaminergic transmission in patients with Parkinson’s disease within one-year follow-up. Journal of Neurology. 2008;255:1059–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0849-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruet NM, Windels FM, Bertrand AB, et al. High Frequency Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus Increases the Extracellular Contents of Striatal Dopamine in Normal and Partially Dopaminergic Denervated Rats. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 2001;60:15–24. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meissner W, Harnack D, Paul G, et al. Deep brain stimulation of subthalamic neurons increases striatal dopamine metabolism and induces contralateral circling in freely moving 6-hydroxydopamine-lesioned rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2002;328:105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meissner W, Harnack D, Reese R, et al. High-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus enhances striatal dopamine release and metabolism in rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2003;85:601–609. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meissner W, Reum T, Paul G, et al. Striatal dopaminergic metabolism is increased by deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in 6-hydroxydopamine lesioned rats. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;303:165–168. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01758-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shon Y-M, Lee KH, Goerss SJ, et al. High frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus evokes striatal dopamine release in a large animal model of human DBS neurosurgery. Neuroscience Letters. 2010;475:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reese R, Winter C, Nadjar A, Harnack D, Morgenstern R, Kupsch A, et al. Subthalamic stimulation increases striatal tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation. Neuroreport. 2008;19:179–182. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f417b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maks CB, Butson CR, Walter BL, et al. Deep brain stimulation activation volumes and their association with neurophysiological mapping and therapeutic outcomes. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2009;80:659–666. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.126219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miocinovic S, Lempka SF, Russo GS, et al. Experimental and theoretical characterization of the voltage distribution generated by deep brain stimulation. Experimental Neurology. 2009;216:166–176. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berk M, Dodd S, Kauer-Sant’anna M, et al. Dopamine dysregulation syndrome: implications for a dopamine hypothesis of bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, Supplementum. 2007:41–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cousins DAa, Butts Kb, Young AHb. The role of dopamine in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders. 2009;11:787–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karachi C, Grabli D, Baup N, et al. Dysfunction of the subthalamic nucleus induces behavioral and movement disorders in monkeys. Movement Disorders. 2009;24:1183–1192. doi: 10.1002/mds.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benarroch EEMD. Subthalamic nucleus and its connections: Anatomic substrate for the network effects of deep brain stimulation. Neurology. 2008;70:1991–1995. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000313022.39329.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilker R, Voges J, Weisenbach S, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation restores glucose metabolism in associative and limbic cortices and in cerebellum: evidence from a FDG-PET study in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2004;24:7–16. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000092831.44769.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroeder U, Kuehler A, Haslinger B, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation affects striato-anterior cingulate cortex circuit in a response conflict task: a PET study. Brain. 2002;125:1995–2004. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ulrike S, Andreas K, Klaus WL, et al. Subthalamic nucleus stimulation affects a frontotemporal network: A PET study. Annals of Neurology. 2003;54:445–450. doi: 10.1002/ana.10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghika J, Villemure J-G, Fankhauser H, et al. Efficiency and safety of bilateral contemporaneous pallidal stimulation (deep brain stimulation) in levodopa-responsive patients with Parkinson’s disease with severe motor fluctuations: a 2-year follow-up review. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1998;89:713–718. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.89.5.0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iacono RP, Shima F, Lonser RR, et al. The results, indications, and physiology of posteroventral pallidotomy for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:1118–1125. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199506000-00008. discussion 1125–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vingerhoets G, van der Linden C, Lannoo E, et al. Cognitive outcome after unilateral pallidal stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1999;66:297–304. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.3.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Visser-Vandewalle V, Temel Y, van der Linden C, et al. Deep brain stimulation in movement disorders. The applications reconsidered. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 2004;104:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Benabid AL, Benazzouz A, Hoffmann D, et al. Long-term electrical inhibition of deep brain targets in movement disorders. Movement Disorders. 1998;13(Suppl 3):119–125. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pollak P, Fraix V, Krack P, et al. Treatment results: Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S75–S83. doi: 10.1002/mds.10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenhouse I, Gould M, Houser J, et al. Dissociating emotion from motor effects of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2011 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cummings JL, Mendez MF. Secondary mania with focal cerebrovascular lesions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;141:1084–1087. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.9.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kulisevsky J, Avila A, Berthier ML. Bipolar affective disorder and unilateral parkinsonism after a brainstem infarction. Movement Disorders. 1995;10:799–802. doi: 10.1002/mds.870100618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kulisevsky J, Berthier ML, Pujol J. Hemiballismus and secondary mania following a right thalamic infarction. Neurology. 1993;43:1422–1424. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.7.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miyawaki E, Perlmutter JS, Troster AI, et al. The behavioral complications of pallidal stimulation: a case report. Brain & Cognition. 2000;42:417–434. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1999.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Appleby B, Duggan P, Regenberg A, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with deep brain stimulation: A meta-analysis of ten years’ experience. Movement Disorders. 2007;22:1722–1728. doi: 10.1002/mds.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Voon V, Krack P, Lang AE, et al. A multicentre study on suicide outcomes following subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 10):2720–2728. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hassan A. Frequency and type of impulse control disorders occurring in Parkinson’s disease patients treated with dopamine agonists in a 2 year retrospective study (Abstract). Presented at 14th International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders; June 2010; Buenos Aires. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lilleeng B, Dietrichs E. Unmasking psychiatric symptoms after STN deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2008;117(Supplement):41–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar R, Lozano AM, Kim YJ, et al. Double-blind evaluation of subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:850–855. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.3.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rodriguez MC, Guridi OJ, Alvarez L, et al. The subthalamic nucleus and tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 1998;13(3):111–118. doi: 10.1002/mds.870131320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schneider F, Reske M, Finkelmeyer A, et al. Predicting acute affective symptoms after deep brain stimulation surgery in Parkinson’s disease. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2010;88(6):367–373. doi: 10.1159/000319046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berney A, Vingerhoets F, Perrin A, et al. Effect on mood of subthalamic DBS for Parkinson’s disease: a consecutive series of 24 patients. Neurology. 2002;59:1427–1429. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000032756.14298.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Funkiewiez A, Ardouin C, Caputo E, et al. Long term effects of bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation on cognitive function, mood, and behaviour in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2004;75:834–839. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2002.009803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Houeto JL, Mesnage V, Mallet L, et al. Behavioural disorders, Parkinson’s disease and subthalamic stimulation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2002;72:701–707. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]