With the focus this year on Part D and with a number of biologic breakthroughs not yet on the market, payers only tinkered with their biopharma management strategies in ’06. New plan designs move more products to the pharmacy benefit and make greater use of HSAs.

Abstract

With an anticipated spate of new products still on the horizon and the need to focus now on Medicare’s new drug benefit, health plans and employers are more likely to tweak than overhaul biologics coverage in 2006. Key trends include higher cost sharing with employees and a continued effort to move biotech drugs from the medical to the pharmacy benefit.

Like a tropical depression far out at sea, employers are keeping an eye on the potential financial impact of biologic therapies on health benefit plans. But they don’t expect that storm to hit land for perhaps a few years. Instead, attention this year will continue to focus on the rollout of Medicare’s prescription drug benefit. “Few plans have had the management bandwidth to focus on anything but Medicare Part D,” says Thomas Baker, vice president for strategy and analytics practice at the San Francisco-based Zitter Group. That means efforts to reconfigure biologics coverage “will be in a holding pattern for a while.”

Randy Vogenberg, RPh, PhD, agrees that Medicare Part D has preempted health plans’ focus on specialty drugs. “There wasn’t a lot of thought or strategy developed for specialty drugs in 2005,” says Vogenberg, national practice leader and senior vice president at Aon Consulting’s life sciences division. “The main question was how to manage Medicare in 2006.”

Another reason why managing biologics isn’t fully capturing payers’ attention is that the dollars involved aren’t yet big enough. “For the most part, payers’ response to specialty drug management has been reactive,” says Vogenberg. “The bottom-line fact for employers is that spending on specialty pharmaceuticals is just now getting to about 5 percent of overall health benefits. To put specialty drugs on their radar screen, the spend would have to grow to 10 or 15 percent, which it probably will in another two to three years.”

Employers, however, are continuing to move biologics from the medical to the pharmacy benefit, which provides more accurate accounting of drug costs. And contracting with specialty pharmacies continues to gain popularity. Research by the Zitter Group found that by last spring, 81.4 percent of managed care plans had contracted with a specialty pharmacy provider, up from 74 percent in fall 2004.

NO OVERHAUL — YET

Observers expect more tweaking of plan design — higher copayments and deductibles based on product tiering, for example. Combining co-insurance with higher copayments for specialty drugs seems to be the favored strategy this year.

“You will see the $5–$10–$20 structure disappear and more of the $15–$30–$60 structure in 2006,” says Bradford L. Kirkman-Liff, DrPH, professor at the School of Health Administration and Policy of Arizona State University’s W. P. Carey School of Business.

For years, commercial health plans have talked about moving beyond such standard benefit designs and integrating the value of a given therapy into coverage schemes, though only a handful have actually traveled that road. Humana is now more than a year into its Rx-Impact benefit design plan — something it calls a return-on-investment management approach to all prescription drugs.

RxImpact groups specialty and traditional therapies by their abilities to prevent a serious medical episode. “Employers need to think about this as an investment,” says William Fleming, PharmD, Humana’s vice president of pharmacy and clinical integration.

Under RxImpact, so-called group A drugs — including drugs for asthma, depression, and juvenile diabetes — are those considered likely to reduce hospitalizations, ER visits, and home health services.

Group B drugs, for such conditions as hypertension, high cholesterol, and cancer, have a longer-term effect. “Take cholesterol drugs, for example,” says Fleming. “If you are diagnosed with heart disease today and start taking the drug, a heart attack is probably several years down the road or may not happen at all.” Medications in group C, which include arthritis and allergy drugs, improve daily functioning but have no return-on-investment tradeoff for the health plan, while group D drugs, include such products as those for acne or weight loss, which often have been excluded from pharmacy coverage.

“An example of where I think there is a good return on investment is the Group A drug Lovenox,” Fleming says of the injectable anticoagulant enoxaparin. “The data are clear. You can use it on an outpatient basis, or if you are in the hospital, we can get you out early. It costs $1,000 for a 10-day supply. Yet, the cost of hospitalization is more than $1,000 a day, plus the cost of the medication.”

As for drug-coverage levels, that is “a value discussion” that depends on the type of business, says Fleming. Employers that keep employees for 25 to 30 years produce retirees. “My advice to them is to cover all Group B drugs until it hurts. Make the allowance model there as high as you possibly can, because the return on investment is in the future with retirees. On the flip side, if your employees come and go, my advice is to cover the Group A drugs until it hurts.”

Humana, which sees its approach as key to controlling specialty costs, expects to have a good sense of its performance by the end of 2006. “We probably are a year away from generating a report with enough power, sample size, and fiscal validity to draw conclusions,” says Fleming. “But early indications are that it’s doing what we want it to do.”

“Specialty drugs will begin to end as a separate category,” says Bradford L. Kirkman-Liff, DrPH, of Arizona State University’s W. P. Carey School of Business. “More drugs will be excluded by health plans as tiering changes, and all patients — including oncology patients — will have to pay more of their drug costs.”

PHOTOGRAPH BY DAVID SCHMIDT

Other forward-looking plans are taking aggressive steps to manage specialty costs while trying to gauge the benefits of biologic therapies.

WellPoint, for instance, launched PrecisionRx Specialty Solutions, a full-service specialty pharmacy, last year. Citing increasing specialty utilization and expenditures (WellPoint says its average monthly cost for a biotech drug is $1,300–$1,400, compared with $45–$50 for traditional drug therapies), WellPoint concurrently formed an office of medical policy and technology assessment to “review for medical necessity” the use of specialty pharmaceuticals.

Similarly, Independent Health, in Buffalo, has established a specialty drug subcommittee. “We put our sharpest pharmacists and physicians around the table to review the products, like we do with all new drugs, and then our full P&T committee reviews them,” says John Rodgers, vice president of pharmacy services.

“Our specialty pharmacy performs the clinical reviews for injectables,” says Rodgers. “It can approve requests, but denials come back through the plan. In addition to getting better unit cost, some of the administrative burden is offset.”

Independent also is raising copayment levels, “which puts costs more into a patient’s decision process,” Rodgers says.

“None of this is wildly innovative. It’s just applying lessons from PBM experience to specialty drugs.”

BETTER COST TRACKING

In moving more drugs from the medical to the pharmacy benefit, health plans are following an example set by Medicare, says Vogenberg. “CMS has done that with oncology and will expand that approach because of Part D. The trend has been to move anything that has an NDC code to the pharmacy side so it’s managed on a cost basis.”

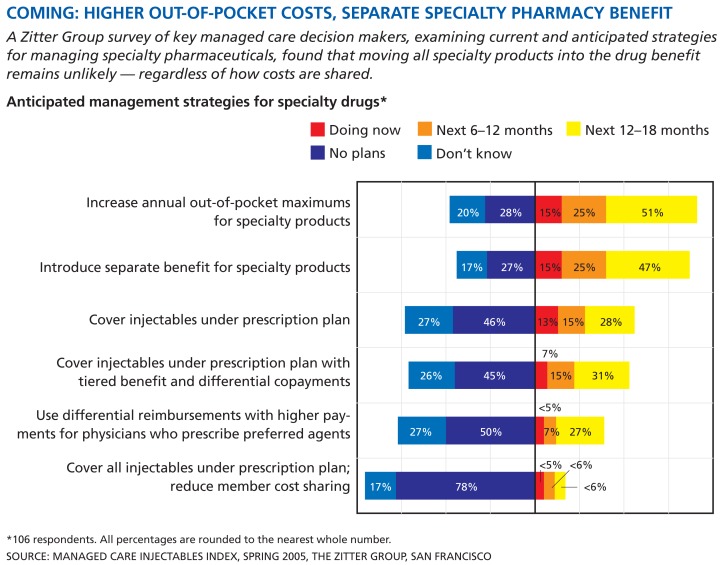

COMING: HIGHER OUT-OF-POCKET COSTS, SEPARATE SPECIALTY PHARMACY BENEFIT

A Zitter Group survey of key managed care decision makers, examining current and anticipated strategies for managing specialty pharmaceuticals, found that moving all specialty products into the drug benefit remains unlikely — regardless of how costs are shared.

Anticipated management strategies for specialty drugs*

*106 respondents. All percentages are rounded to the nearest whole number.

SOURCE: MANAGED CARE INJECTABLES INDEX, SPRING 2005, THE ZITTER GROUP, SAN FRANCISCO

Baker agrees. “The trend is toward more pharmacy classification. This is an area where we will see more offerings from specialty pharmacies and PBMs that include all drugs as part of a managed pharmacy benefit.”

Another aspect of moving biologics to the pharmacy benefit is improved patient compliance tracking, says Stephen Lash, PharmD, national managed care liaison at Genentech. “For example, health plans will find it easier to track injectable treatments, like Remicade [infliximab], on the pharmacy side because PBMs have created user-friendly programs designed to make measuring compliance easier.

“The medical benefit is often managed much like a finance function — the doctor bills the health plan, the health plan pays the bill— but systems like that are not designed to monitor patient compliance,” Lash says.

Compliance oversight and cost management are the primary reasons for moving specialty drugs to the pharmacy benefit, though not all medications are suitable for removal from the medical benefit.

“We take a rational approach to specialty pharmacy,” says Diana Kycia, Cigna’s assistant vice president of specialty pharmacy. “Our coverage policies recognize that administration [of medications] can take place in different settings.”

Cigna has defined a list of self-injectables covered exclusively under the pharmacy benefit, Kycia says, which includes drugs for hepatitis C, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis. “Point-of-service pharmacy claim adjudication allows for earlier identification of members who will benefit from clinical programs focused on conditions treated with specialty medications.” This, she says, effectively engages the patient more in his or her own treatment regimen.

Placing greater emphasis on self-injectables and other products that can be placed in the pharmacy benefit, however, also carries risk. “If [a drug] is not covered as part of a physician office visit but is covered under the pharmacy benefit, there’s always the risk of increased utilization,” says Kirkman-Liff. “Employers must be careful that if they increase the patient’s share of the cost, they don’t see a jump in utilization.”

Medicare Part D promises — some would say threatens — to shape the design of future health benefit plans, especially with respect to specialty drugs.

Benefit changes that contribute to higher utilization will catch the eye of purchasers. “Employers will always be nervous about any expansion in medication use that isn’t based on evidence, and we certainly are going to worry about cost and safety issues,” says Helen Darling, president of the National (formerly the Washington) Business Group on Health. Moreover, she thinks, greater use of self-injectables may necessitate additional management services. “Anybody who has been around a while tends to be skeptical about arguments that something is less expensive in the home, because often that is not true.”

The biggest issue relative to self-administration, Baker says, is that payers believe patients prefer it — a consistent finding in Zitter’s studies. Patients prefer not to go the physician to take a drug but to do it when and where it’s comfortable, he says. “It’s cheaper for the payer and more convenient for the patient — that’s a tough combination to crack.”

EYEING THE PART D MODEL

The emergence of biologics has coincided with the ascent of the consumer-directed health plan and its many variations, which will change employee-purchasing patterns, says Deloitte’s 2005 Consumer-Driven Health Care Survey. With a projected 8 percent increase in employer-sponsored healthcare costs this year, expect employers to shift more expense to employees.

“There is a trend to use health savings accounts,” says Kirkman-Liff. “The pharmacy benefit may include drugs that are not covered under the consumer-directed health plan but are covered under the patient’s HSA. Members may have to pay some of the cost of biologics out of their HSAs.”

The very structure of Medicare Part D may be a precursor to just that sort of thing. The form Part D eventually takes promises — some would say threatens — to shape the design of future health benefit plans, especially where specialty drugs are concerned. So far, payers are using existing systems, policies, and plan design, at least for the rest of 2006, Baker says. Because the Part D design with the doughnut hole1 is a relatively thin benefit — thinner than most commercial offerings — Baker expects to see more Medicare-type designs in the commercial sector. “There will be more privatization of risk, higher cost sharing, much less access to care dollars, and higher deductibles.”

Trends in Pharmacy Reimbursement: A Discussion With Zitter Group’s Thomas Baker.

The Zitter Group recently published its Zitter 2005 Managed Care Injectables Index, a quantitative Web-based survey with 106 managed care decision makers from large and important regional and independent managed care plans. Thomas Baker, the San Francisco consulting firm’s vice president of strategy and analytics practice, discussed the survey results with Senior Editor Katherine T. Adams.

BIOTECHNOLOGY HEALTHCARE: A key finding of your survey is that specialty-management savings from reduced reimbursements, specialty contracts, and self-administration are nearing exhaustion and cost sharing is trending upward. But interest in carved-out designs has risen significantly. Is this where specialty pharmacy is headed in 2006?

BAKER: Easy savings are essentially exhausted, so payers have to look at other avenues. Previously, they just clamped down on payments to physicians. In 2006, out-of-pocket costs may increase modestly. Interestingly, there will be more demand on manufacturers for price concessions in the form of contracted price reductions. As much as MCOs complain about the cost of specialty products, the reality is that the actual per-member per-month cost is small compared to hospitalizations, or even money spent on rofecoxib [Vioxx] or sildenafil [Viagra]. Our newest survey indicates that interest in carve-outs is decreasing.

BH: Along with slowing premium growth, influencing patient choice is a major objective for 2006. How will MCOs influence which products patients choose?

BAKER: MCOs want patients to at least ask if there’s a cheaper option. They want the patient to do another round of conventional therapy — to choose a nonspecialty or nonbiologic product first.

BH: How do health savings accounts and consumer-directed health plans play into patient choice? Research by you and others show a decline in patient compliance and in coverage over time.

BAKER: Our recent focus group with MCOs asked that question. There’s some hope that health savings accounts are going to be a great boon. In reality and for the most part, enrollees are younger, healthier people. The major question remains unanswered: How can an organization manage its risk pool if young, healthy people pay less into that pool and sicker people don’t want to expose themselves to the HSA, but still want traditional coverage? Their premiums and out-of-pocket costs are going to go up. It’s not a particularly good model for patients who need a specialty drug therapy.

BH: Your statistics reveal a tension between health plans and providers in terms of physician reimbursement, with physicians actively resisting. With health plans saying they want to encourage self-administration and to use community infusion centers and hospital outpatient centers, how will reimbursements change?

BAKER: It depends on the provider group — and, obviously, oncologists are the biggest stumbling block here. Most payers plan to follow Medicare’s lead, and most organizations now expect to adopt average-sales price-based reimbursement by the end of 2006. This will have a significant effect on choice and access to care for oncology products. Other specialists, with the exception of hematologists and rheumatologists, tend to be less reliant on drug revenue. I expect that groups like rheumatologists and oncologists will react more aggressively to forestall reimbursement reductions, as has been the case. But as Medicare Part D goes online, you’ll see more commercial payers topping Medicare payment rates. The threats these specialists have used, such as “We’re not taking any more patients,” or “We’re going to send your patients to hospitals,” haven’t worked. That’s partly because payers realize that they were paying those specialists so much, that they’ll be no worse off, and possibly better off, sending patients somewhere else.

BH: Patient compliance and monitoring services may cause costs to rise over time, because most specialty pharmacy providers can’t provide that kind of service cost-effectively — or can they?

BAKER: The challenge is that many vendors have said they can, that it’s still cheaper than buy and bill. That may be true. No one knows for sure. Payers have not awakened to the fact that compliance with specialty products is not significantly better than with any small-molecule product. Once they do, and they realize that the cost implications of that are negative, they probably will want to do more around compliance monitoring.

Thomas Baker

Lash, of Genentech, isn’t as sure how Part D will affect commercial health plans, although he points out that patients who require biologics will quickly push through the doughnut hole and will have catastrophic coverage thereon.

WILL PRICES FALL?

However benefit designs evolve, it’s clear that patients of all ages will bear a greater share of the cost of specialty drugs. Although the federal government has not attempted to regulate the price of biologic therapies, the absence of follow-on products means that as Part D meshes with commercial plans, the temptation to impose price controls will grow. “I think it’s going to be really hard for them not to,” cautions the NBGH’s Darling. “So it’s incumbent on the industry to be as careful as possible to avoid regulation by making certain that there is not inappropriate use of biologics.”

Segal’s 2006 Health Plan Cost Trend Survey projects that specialty drug spending will increase by 21.6 percent this year. This comes at a time when there are 260 biologics on the market and another 1,400 in development. Consider that in the context of the cost of some popular biologic therapies, such as Novartis’ imatinib mesylate (Gleevec), for chronic myeloid leukemia (yearly average, $37,000), and Biogen Idec’s interferon beta-1a (Avonex), for multiple sclerosis (average, $14,000).2

Will payers try to muscle prices for specialty drugs down? Possibly, says Kirkman-Liff. “There is consolidation in the health insurance industry. I think we will see more aggressive negotiation by insurers on price with manufacturers.”

Yet, with the lack of follow-on specialty drugs, employers don’t have much negotiating flexibility, says Vogenberg. Many specialty drugs, like Genentech’s bevacizumab (Avastin), are the standard of care. “It illustrates the problem we still have around a misalignment of incentives across the healthcare system. What’s good for an employer may be bad for the health plan and for the employee.”

Vogenberg doubts that price decreases, if any, will be significant. “The way the market and average sales prices move, [manufacturers] have no incentive to lower prices.”

“Some payers favor the use of blunt instruments like higher copayments, but does this really create leverage?” Lash asks. “If entire classes of treatment are subject to similar increases, then what’s the benefit to product discounts?” But Lash believes that blunt instruments — such as putting all specialty drugs in the third tier — exist because “not all payers have the expertise needed to sort out high-tech products using evidence-based medicine as a guide.”

After all, trying to understand how reengineered human proteins work to treat a disease or maintain quality of life necessitates a background, education, and expertise that employers and other payers don’t yet have. Add to that the fact that diagnostics is one of the fastest growing areas of medicine today, and that personalized or targeted medicine is looming on the horizon, and payers’ plates simply may be too full.

More payers probably will acquire specialty pharmacies this year, given that the larger payers can demand (and obtain) price concessions more easily. Having a specialty pharmacy will become practically a must. “The holdouts,” Baker says, “will be the oncologists and rheumatologists.”

LOOKING AHEAD

With the biologics pipeline predicted to explode by 2010, is there a bottom line here? “We’re just seeing the tip of the iceberg. The good news is nothing dramatic is going to happen right now,” says Vogenberg. “The bad news is that there will be a lot going on fast, and by the time many of these products get to market, they are going to be in a very different benefits world than they are in 2006.”

Footnotes

In 2006, the average premium is expected to be $37.37 per month, with a $250 deductible, according to the National Committee to Preserve Social Security and Medicare. The benefit is structured so that Medicare will provide a 75 percent copayment up to $2,250 in covered drug costs. The beneficiary then pays 25 percent. At that point, the Medicare benefit stops completely, and Part D enrollees will be fully responsible for the next $2,850 in covered drug costs — the so-called doughnut hole. Once the threshold of $5,100 in covered drug spending is reached, catastrophic coverage begins, and the beneficiary’s copayment drops to 5 percent for covered drug costs above that amount for the rest of the year. By the time a Part D enrollee reaches the $5,100 catastrophic threshold, he or she will have spent $3,600 in out-of-pocket costs for covered drugs, in addition to the expected $448 in premiums.

“How Drugs for Rare Diseases Became Lifeline for Companies.” The Wall Street Journal, Nov. 15, 2005.