Abstract

Background

There is little information on the role of bisphosphonates and bone mineral density (BMD) measurements for the follow-up and management of bone loss and fractures in long-term kidney transplant recipients.

Methods

To address this question, we retrospectively studied 554 patients who had two BMD measurements after the first year posttransplant and compared outcomes in patients treated, or not with bisphosphonates between the two BMD assessments. Kaplan-Meier survival and stepwise Cox regression analyses were performed to examine fracture-free survival rates and the risk-factors associated with fractures.

Results

The average time (±SE) between transplant and the first BMD was 1.2±0.05 years. The time interval between the two BMD measurements was 2.5±0.05 years. There were 239 and 315 patients in the no-bisphosphonate and bisphosphonate groups, respectively. Treatment was associated with significant preservation of bone loss at the femoral neck (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.21-2.06, P=0.0007). However, there was no association between bone loss at the femoral neck and fractures regardless of bisphosphonate therapy. Stepwise Cox regression analyses showed that type-1 diabetes, baseline femoral neck T-score, interleukin-2 receptor blockade, and proteinuria (HR 2.02, 0.69, 0.4, 1.23 respectively, P<0.01), but not bisphosphonates, were associated with the risk of fracture.

Conclusions

Bisphosphonates may prevent bone loss in long-term kidney transplant recipients. However, these data suggest a limited role for the initiation of therapy after the first posttransplant year to prevent fractures.

Keywords: Bisphosphonates, Kidney transplantation, Osteoporosis, Osteopenia, Dexa scan

Mineral bone disease is a common finding in long-term (>1 year) kidney transplant recipients. It results from risk-factors commonly associated with a longstanding history of pretransplant chronic kidney disease (CKD), including diabetes, secondary hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism, metabolic acidosis, and poor nutrition and early post-transplant insults including steroids, hypophosphatemia, and persistent hyperparathyroidism (1-4). Both decreased bone mineral density (BMD) and increased fracture rates have been commonly described in the late posttransplant period (1-4). The rate of posttransplant bone loss is significantly greater in the initial 6 to 12 months, primarily because of high-dose steroids (5, 6). However, even with a decrease in steroid dose after the first 6 months, the annual rate of bone loss is approximately 1% (7). Fracture rates, already high in the dialysis population, rise further after transplantation (4, 8). It is therefore important to define transplant-specific risk factors and treatment strategies to address bone disease and fractures in kidney transplant recipients.

Bisphosphonates are antiresorptive agents commonly used in the treatment of posttransplant bone disease (9). They have a high affinity for bone tissue and are rapidly absorbed onto the bone surface, inhibiting osteoclast activity and resulting in cell death. Although there is evidence that these drugs slow the rate of bone loss in kidney transplant recipients (3, 9-11), there is no data demonstrating a preventive effect on fractures (1, 7, 9). Yet bisphosphonates are commonly used in the late posttransplant period including in patients with suboptimal kidney allograft function. They are not inexpensive and may have significant adverse effects including glomerular injury (12, 13), jaw necrosis (14), esophageal irritation (15, 16), and adynamic bone disease (11). We aimed to determine whether bisphosphonate therapy prevents bone loss and fractures after the first posttransplant year, and examined demographic and biochemical risk factors for fractures in this context.

METHODS

Patient Selection and Data Collection

The University of Wisconsin Division of Transplant Surgery maintains a database of all transplant recipients and their follow-up. Because this study was designed to examine the effects of bisphosphonates on BMD and fractures after the first posttransplant year, we retrospectively evaluated all kidney transplant recipients from the database who had at least two BMD measurements after the first year of transplant, which covered the period of 1998-2006. Data were collected regarding patient’s baseline characteristics and laboratory values at the time of the first and second BMDs (BMD1 and BMD2, respectively). These included age, sex, race, body mass index (BMI), cause of end-stage kidney disease including diabetes mellitus (DM) type 1, DM2, hypertension, glomerular disease, hereditary or interstitial, type of transplant (kidney-pancreas [KP], living donor, or deceased donor), number of rejection episodes, times retransplanted, bone fractures (number and type), length of pretransplant dialysis, serum creatinine (Scr), urine protein to creatinine ratio (UPC), serum calcium (Ca), phosphorus, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT), biointact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), bicarbonate, and albumin. We also obtained records of all immunosuppressive medications including alemtuzumab (Campath), basiliximab, antithymocyte globulin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, sirolimus, prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and medications used to treat bone disease (calcium, ergocalciferol, active vitamin D, calcitonin, and bisphosphonates). All analyses were performed with the approval of the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Institutional Review Board.

Study Design

Patients on bisphosphonate therapy before BMD1 and those with Charcot fractures after BMD1 were excluded from the study to improve the homogeneity of the analyses, and better evaluate the potential effect of bisphosphonates on bone loss and fractures. Outcomes were defined by the incidence of bone loss or fractures. Bone loss was determined by comparing femoral neck T-scores at BMD1 (H1) and BMD2 (H2), and lumbar spine (LS) T-scores at BMD1 and BMD2 (LS1 and LS2, respectively). Fractures were primarily self-reported and counted if they occurred during the interval between BMD1 and BMD2. Radiographic studies were therefore not available for all fractures. Data collected from the database were used to calculate further variables for the analysis. The serum creatinine measured by the kinetic alkaline picrate method was used to calculate the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (eGFR=175×standardized Scr-1.154×age-0.203×1.212 [if black]×0.742 [if female]).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using the Student’s t test and Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical data, respectively. Univariate Cox regression analyses were performed to determine independent covariates affecting fractures. These covariates included age, sex, race, BMI, cause of end-stage kidney disease, type of transplant, number of rejection episodes, times retransplanted, length of pretransplant dialysis, biochemical characteristics such as Scr, UPC, alkaline phosphatase, γ-GT and iPTH, immunosuppressive regimen (induction and maintenance) and drugs used for bone mineral metabolism including calcium, vitamin D and analogs, and bisphosphonates. Those variables that were statistically significant (P≤0.05) were then entered into stepwise multivariable Cox regression analyses. Variables were retained if P value was less than 0.05 and dismissed if P value was more than 0.1. Next, fracture-free and bone-loss-free survival rates were modeled using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The time interval was T1 (time of BMD1) and T2 (time of BMD2). Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2003, version 11.8012.6568 and MedCalc, version 9.3.0.0. A P value of less than or equal to 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

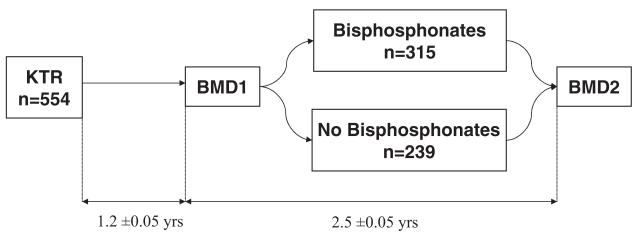

A total of 554 kidney transplant recipients underwent two consecutive BMD measurements after the first posttransplant year (Fig. 1). The average time (±SE) between transplant and the first BMD was 1.2±0.05 years and the time interval between the two BMD measurements was 2.5±0.05 years. Overall, patients were followed for 3.72±0.07 years after transplant. Three hundred fifteen patients were started on bisphosphonates after BMD1, whereas 239 patients did not receive any bisphosphonate therapy.

FIGURE 1.

Study design: bisphosphonate therapy after the first posttransplant year. KTR: kidney transplant recipients, BMD1: first bone mineral density, BMD2: second bone mineral density. Time interval (average±SE) displayed between the time of transplant and BMD1 and between BMD1 and BMD2.

Baseline Characteristics

Table 1 represents the baseline characteristics in the bisphosphonate and no bisphosphonate groups. There were more diabetic patients in the bisphosphonate group with a lower average BMI and greater time on dialysis. Patients in this group also received more transplants, vitamin D, and tacrolimus, but less basiliximab and cyclosporine. Biochemical characteristics at the time of the first BMD were not significantly different except for a higher alkaline phosphatase level in the bisphosphonate group.

TABLE 1.

Baseline and bone characteristics

| Variable | No. bisphosphonate | Bisphosphonate | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 239 | 315 | |

| Age (yrs) | 46.9±0.2 | 45.9±0.7 | ns |

| Female, N (%) | 109 (46) | 125 (40) | ns |

| BMI | 27.2±0.3 | 25.5±0.2 | <0.001 |

| HD time pretransplant (mos) | 11.5± 1.0 | 18.6±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Rejections, N (%) | 67 (28) | 85 (27) | ns |

| Average transplant number | 1.08±0.02 | 1.19±0.02 | 0.005 |

| Cause ESRD | |||

| DM-1, N (%) | 41 (17) | 101 (32) | <0.001 |

| DM-2, N (%) | 28 (12) | 31 (9) | ns |

| Glomerulonephritis, N (%) | 61 (26) | 71 (23) | ns |

| Hereditary, N (%) | 45 (19) | 41 (13) | ns |

| HTN, N (%) | 21 (9) | 32 (10) | ns |

| Type of transplant | |||

| Deceased donor, N (%) | 98(41) | 143 (45) | ns |

| Kidney-pancreas, N (%) | 36 (15) | 77 (24) | 0.009 |

| Living donor, N (%) | 106 (44) | 95 (30) | ns |

| Bone Rx | |||

| Calcium, N (%) | 170 (71.1) | 220 (69.8) | ns |

| Vitamin D, N (%) | 35 (14.6) | 83 (26.3) | 0.001 |

| Active vitamin D, N (%) | 11 (4.6) | 39 (12.4) | 0.003 |

| Transplant drugs | |||

| Thymoglobulin, N (%) | 19 (8) | 37 (11.7) | ns |

| Alemtuzumab, N (%) | 35 (14.6) | 62 (19.7) | ns |

| Cyclosporine, N (%) | 117(49) | 126 (40) | 0.04 |

| IL-2 antagonist, N (%) | 159 (66.5) | 180 (57.1) | 0.03 |

| Mycophenolic acid, N (%) | 206 (86.2) | 270 (85.7) | ns |

| Prednisone, N (%) | 211 (88.3) | 293 (93) | ns |

| Sirolimus, N (%) | 17 (7.1) | 31 (9.8) | ns |

| Tacrolimus, N (%) | 91 (38) | 148 (47) | 0.04 |

| Chemistry at BMD-1 | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.01 ±0.02 | 4.01 ±0.02 | ns |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 99.8±2.5 | 121.5±3.6 | <0.001 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 24.4±0.2 | 24.2±0.2 | ns |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.6±0.03 | 9.7±0.03 | ns |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 52± 16.8 | 53.9±17.7 | ns |

| γ-GT (U/L) | 51.8±3.2 | 61.7±4.8 | ns |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.5±0.03 | 1.47±0.02 | ns |

| Urine P:C (g/g) | 0.36±0.03 | 0.39±0.05 | ns |

| Bone characteristics | |||

| Femoral neck T-score on BMD-1 | 1.0±0 | −1.9± 1 | <0.0001 |

| Lumbar spine T-score on BMD-1 | 1.3±0.5 | −1.4± 1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Femoral neck T-score on BMD-2 | -1.0±1.0 | −1.7± 1 | <0.0001 |

| Lumbar spine T-score on BMD-2 | 0± 1.4 | −1.0±1.3 | <0.0001 |

| Bone loss per 100 patient years (femoral neck) | −0.026 | 0.03 | <0.0001 |

| Bone loss per 100 patient years (LS) | −0.015 | 0.04 | 0.001 |

| Patients with fractures (%) | 16(7) | 56 (18) | 0.0002 |

| Fractures per 100 patient years | 3.67 | 9.96 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with fractures (%) after BMD-2 | 7 (3) | 16 (5) | 0.04 |

| Femoral neck fractures | 0 | 3 | ns |

| Vertebral fractures | 0 | 3 | ns |

| Other fractures | 16 | 50 | 0.003 |

ESRD, end-stage renal disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; IL, interleukin; BMD, bone mineral density; eGFR, estimated glomerulus filtration rate; y-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; LS, lumbar spine.

Bone Loss and Fractures

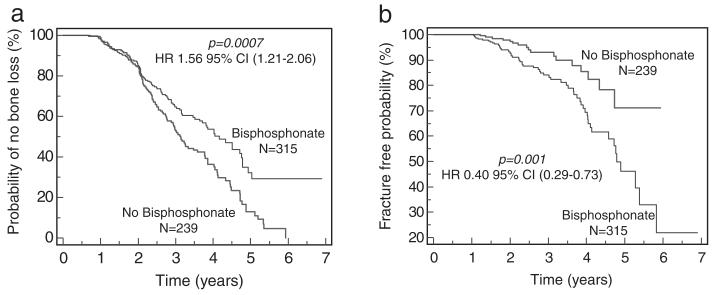

Not surprisingly, patients in the bisphosphonate group had lower average femoral neck and lumbar-spine T-score levels at baseline (Table 1). These levels remained significantly lower than the no-treatment group at follow-up (BMD2) despite lower rates of bone loss. There were significantly more patients with fractures in the treatment group (56 vs. 16, P=0.0002). Fractures remained more prevalent in the bisphosphonate group even after BMD2 (16 vs. 7, P=0.04) confirming that the increase in bone density observed between BMD1 and BMD2 did not prevent late fractures. Because bone loss and fractures are time-dependent variables, we looked at bone loss-free and fracture-free survival probabilities using Kaplan-Meier analyses (Fig. 2). These studies showed that bisphosphonate therapy was associated with significant preservation of bone loss at both the femoral neck (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.21-2.06, P=0.0007) and lumbar-spine (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.13-1.98, P=0.004, data not shown); yet, treatment was also associated with significantly decreased probability of fracture-free survival (HR 0.40 95% CI 0.29-0.73, P=0.001).

FIGURE 2.

Bisphosphonates were associated with lower bone loss and higher fracture rates. (a) Bisphosphonates were associated with lower rates of bone loss at the femoral neck. (b) Bisphosphonates were associated with increased fracture rates.

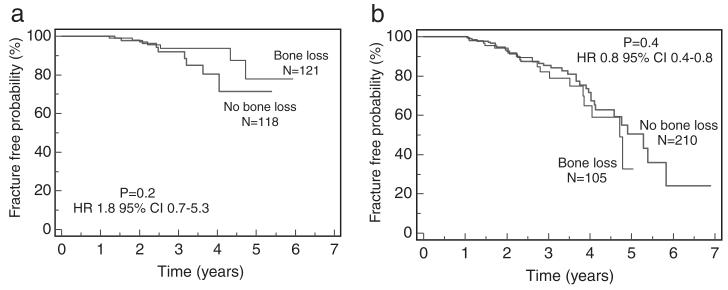

We next compared fracture-free survival rates in patients with or without bone loss and showed that there was no association between bone loss and fractures regardless of bisphosphonate therapy (Fig. 3). When we evaluated fracture rates according to the severity of baseline femoral neck BMD scores, we found that only patients with the diagnosis of osteoporosis (baseline femoral neck T-score <–2.5) had significantly decreased fracture rates if treated with bisphosphonates (HR 6.7 95% 6–6284, P=0.003). However, there were only three patients in the no-treatment group with a 95% CI that was large.

FIGURE 3.

There was no association between the rate of bone loss and fractures, regardless of bisphosphonate use. (a) No association between rate of bone loss and fractures in patients off bisphosphonates. (b) No association between rate of bone loss and fractures in patients on bisphosphonates.

Univariate and Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses

In univariate analyses, the following variables were associated with a significant increase in fracture risk (Table 2): presence of DM-1, low femoral neck, and LS T-score on baseline BMD, bisphosphonate therapy, no interleukin (IL)-2 antagonist therapy, low serum calcium, high alkaline phosphatase, γ-GT, and UPC levels. In stepwise Cox regression multivariable analyses, only five covariates including DM-1, baseline Femoral neck T-score, IL-2 receptor block-ade, γ-GT and UPC levels were retained as significant factors associated with the risk of fracture (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cox regression analyses

| Univariate |

Multivariable |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI |

| DM-1 | <0.001 | 2.50 | 1.57–3.99 | 0.01 | 2.02 | 1.1822–3.4846 |

| Femoral neck BMD1 | <0.001 | 0.64 | 0.53–0.78 | 0.0009 | 0.69 | 0.5657–0.8628 |

| Lumbar-spine BMD1 | 0.015 | 0.82 | 0.69–0.96 | — | — | — |

| Bisphosphonates | 0.001 | 2.84 | 1.58–5.08 | — | — | — |

| IL-2 antagonist | 0.017 | 0.56 | 0.35–0.90 | 0.0003 | 0.40 | 0.2464–0.6591 |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | — | — | — |

| Serum calcium | 0.010 | 0.57 | 0.37–0.87 | — | — | — |

| γ-GT | <0.001 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.01 | <0.0001 | 1.005 | 1.0034–1.0076 |

| UPC | 0.005 | 1.24 | 1.07–1.44 | 0.01 | 1.23 | 1.0487–1.4508 |

DM, diabetes mellitus; BMD, bone mineral density; γ-GT, gamma-glutamyl transferase; IL, interleukin.

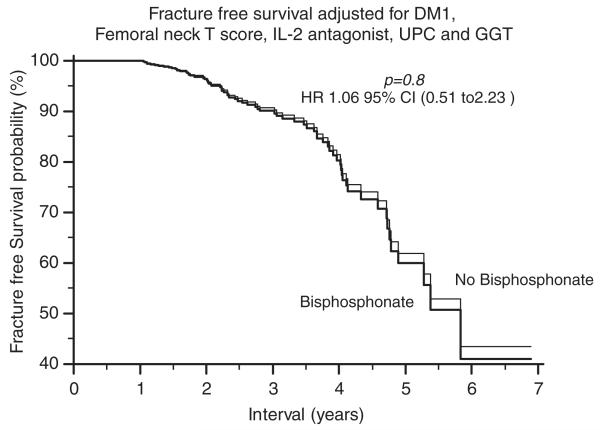

We then compared fracture-free survival probabilities between the bisphosphonate and no-bisphosphonate groups and included all the above five variables. Interestingly, the difference in unadjusted analyses (Fig. 2b), disappeared in multivariable analyses (Fig. 4), suggesting that bisphosphonate therapy did not have a significant effect on fracture rates in long-term kidney transplant recipients.

FIGURE 4.

Adjusted fracture-free survival probabilities.

Age, gender, BMI, time on dialysis before transplant, number of rejections, number of transplants, transplant type (live, deceased, KP), immunosuppression other than IL-2 receptor blockade, calcium or vitamin D supplementation, eGFR, serum creatinine, iPTH, bicarbonate, and albumin levels were not associated with fractures in uni- or multivariable analyses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective study of long-term kidney transplant recipients, bisphosphonate therapy was associated with the improvement in BMD but no decrease in fractures. Sub-group analyses showed a potential benefit for fracture rates in patients with osteoporosis (femoral neck T-score <−2.5), although the sample size in the untreated group was small. Interestingly, bone loss between the two BMD measurements was not associated with the risk of fracture regardless of bisphosphonate therapy. Multivariable analyses showed that DM-1, baseline femoral neck T-score, IL-2 receptor blockade, γ-GT levels, and proteinuria were significant risk-factors associated with fractures. Overall, these observations suggest a limited role for the broad use of bisphosphonates in the late posttransplant period. Furthermore, the lack of relationship between BMD loss and fractures highlights the difficulties to accurately assess the progression of post-transplant bone disease.

Bisphosphonates have beneficial effects in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis where they reduce the number of fractures and increase BMD at both trabecular and cortical sites (17, 18). However, there is no information whether these drugs prevent fractures in long-term (after the first year) kidney transplant recipients (1). In fact, as most transplant recipients have a low-turnover bone disease, inhibition of osteoclasts with bisphosphonates might further reduce osteoblast activity and promote osteoid synthesis. Only three randomized control trials evaluated the effects of bisphosphonates on BMD in the late posttransplant period (5, 19, 20). Grotz et al. (19) randomly assigned 46 patients with osteopenia or osteoporosis (BMD ≤1.5 SD below normal) to daily oral clodronate (800 mg), intranasal calcitonin (200 IU) for 2 weeks every 3 months and control. Every patient was supplemented with 500 mg of calcium per day. Bone mineral density was measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) at the lumbar spine and femoral neck before and after the 12-month treatment period. Bone mineral density at the lumbar spine was increased by 4.6% in the clodronate group (n=15, P=0.005), by 3.2% in the calcitonin group (n=16, P=0.034), and by 1.8% in the control group (n=15, P=0.265). However, the differences in BMD changes among the groups were not statistically significant (19). In another study, 40 patients were randomized into two groups for 12 months: alendronate (10 mg/day), calcitriol (0.5 μg/day), and calcium carbonate (500 mg/day) compared with calcitriol (0.5 μg/day), and calcium carbonate (500 mg/day) alone without bisphosphonate therapy (20). Calcitriol and calcium treatment alone stabilized bone loss but bone density of the spine (+5.0±4.4%), femoral neck (+4.5±4.9%), and total femur (+3.9±2.8%) increased significantly in the alendronate-treated patients only. It was concluded that the association of the three drugs was advantageous to control the complex abnormalities of skeletal metabolism encountered in long-term kidney transplant subjects. Finally, Jeffery et al. (5) randomized 117 long-term kidney transplant recipients with a reduced BMD (T score ≤-1) to treatment with alendronate and calcium (n=60) versus calcitriol and calcium (n=57). There was no significant BMD loss during 2.7 years of followup. The average lumbar spine and femoral neck BMD increased significantly with both alendronate and calcitriol treatment suggesting that 1 year of treatment with alendronate or calcitriol, both with calcium supplementation, resulted in significant increases in BMD at the lumbar spine and femur. In aggregate, these studies showed that the use of bisphosphonates, in combination with calcium and vitamin D may result in the prevention of bone loss in long-term kidney transplant recipients. However, there was no information on the effects of these drugs on fractures. The failure to demonstrate a reduction of fracture rate may result from in-adequate statistical power of the above studies or a genuine absence of a significant impact of bisphosphonates in this patient group (6, 9). Indeed native and transplant CKD differ importantly from each other (21, 22), and from the general population. Therefore, BMD that is only one of the determinants of bone strength may not appropriately characterize bone “quality” in these patients.

In our study, despite improvements in BMD, more patients experienced fractures while on bisphosphonates. Only patients with baseline osteoporosis at the femoral neck (T score <−2.5) seemed to have reduced fractures with antiresorptive therapy. Although these observations challenge both the wide-use of bisphosphonates and the use of follow-up DEXA measurements in long-term kidney transplant recipients, one needs to consider that posttransplant bone disease is a disorder far more complex than osteoporosis and osteopenia. Both preexisting bone disease (osteomalacia, adynamic bone disease, osteitis fibrosa, and mixed bone disease) and posttransplant factors including kidney allograft function, hyperparathyroidism, hypophosphatemia, and immunosuppression result in greater rates of bone loss and fractures compared with patients with native CKD (1). Therefore, x-ray based bone absorptiometry measurements may not be the most accurate assessment of posttransplant bone disease. In fact, although baseline femoral neck T-scores were an independent predictor of fractures in our study, the presence of low BMD as a risk factor for fracture in kidney transplant recipients remains controversial (1,8,23). For example, Grotz et al. (8) evaluated the relationship between DEXA measurements in 100 graft recipients (mean interval 63±53 months after transplantation) and the incidence of fractures and showed that fractures occurred in patients with both low and normal BMD. DEXA at the femoral neck or lumbar spine proved to be of limited or no value to predict fractures. In another study, changes in spinal, femoral neck, and total body BMD were assessed using DEXA measurements in kidney transplant recipients with a minimal follow-up of 5 years after transplantation (23). The investigators examined the correlation between DEXA values and fractures, and showed that more than one-third of fractures occurred in patients with no BMD criteria of osteoporosis, suggesting that BMD assessment does not discriminate patients at risk for fractures from those not at risk (23). In summary, BMD evaluates bone quantity and not bone quality and its predictive value for fractures in kidney transplant recipients is inconsistent given the complex nature of bone disease in this group of patients.

We also evaluated the association of other variables at the time of first BMD measurement with fractures. DM-1, γ-GT and proteinuria were positively associated with fractures whereas the use of IL-2 antagonists had a negative predictive value. The negative effects of DM on fractures in kidney transplant recipients were observed in two other studies (24, 25). First, in a retrospective analysis of 1572 kidney transplant recipients with 6.5±5.4 years of follow-up, fractures occurred in 300 patients (19.1%) and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses showed that kidney failure from DM-1 and DM-2 increased fracture risk by 2.08 and 1.92, respectively (24). In another study of long-term kidney transplant recipients, 117 fractures were observed during a follow-up extending to 33 years. In multivariate analyses, age and diabetic nephropathy were independent predictors of fracture risk (25). Limited information is available regarding posttransplant bone fractures and newer immunosuppressive drugs including IL-2 receptor blockers. Basiliximab as an induction immunosuppressive agent was associated with a 62% reduction in the risk of fractures in our study. We are not aware of any direct role of IL-2 receptor blockers on bone metabolism. One explanation could be that basiliximab was used in healthier patients at a lower risk of fractures. Indeed, fewer patients in the bisphosphonate group (more fractures) received IL-2 blockade. This same group had greater numbers of retransplants, type 1 diabetes, and combined KP transplants, suggestive of a greater overall corticosteroid exposure and mineral bone metabolism disease burden. The concept of plasmaγ-GT as a biomarker of bone disease and fracture is an interesting one. Animal studies recently showed that γ-GT overexpression in transgenic mice accelerated bone resorption and caused osteoporosis (26). Furthermore, elevated urinary γ-GT levels in mice were associated with increased bone turnover (27) and in vitro studies showed that γ-GT acts on osteoclast formation independent of its own enzymatic activity (28). Plasma γ-GT levels may therefore have a potential role as a marker of increased bone turnover and fractures in kidney transplant recipients. Finally, the correlation between proteinuria and bone fractures in kidney transplant recipients has not been reported. However, a recent study found that proteinuria and more specifically albuminuria, was a risk factor for fractures in nondiabetic women, suggesting a relationship between structural kidney disease and bone mineral metabolism in nontransplant patients (29).

Age, gender, BMI, time on dialysis before transplant, number of rejections, number of transplants, transplant type (live, deceased, KP), calcium or vitamin D supplementation, eGFR, serum creatinine, iPTH, bicarbonate, and albumin levels were not associated with fractures in uni/multivariable analyses (data not shown). Kidney transplant recipients present unique characteristics that separate them from patients with native CKD, mainly because of disease vintage resulting from past CKD and the immunosuppressive therapy (21, 22, 30). Therefore, some of these variables considered as common risk-factors for fractures in patients with native CKD may not be suitable to predict outcomes in kidney transplant recipients.

Our study is limited by its retrospective single-center nature, the lack of centralized measurements of BMD, data on hormone replacement, testosterone, selective estrogen receptor modulators, fluoride or anabolic steroids, dose of corticosteroids, and the absence of a uniform approach to the treatment of posttransplant bone disease. Furthermore, we had no data on the standard biochemical markers of bone turnover. However, we provide the first and largest set of analyses on long-term kidney transplant recipients treated with bisphosphonates and the association of treatment with fractures. Bisphosphonates may be valuable in preventing bone loss. However, posttransplant bone disease is more complex that renal osteodystrophy in patients with CKD, and our data suggest that only patients with femoral neck osteoporosis may benefit from treatment and reduced fracture rates. Though these results need confirmation and given cost and side-effect considerations, cautious use of these drugs in the late posttransplant period is advised. New prospective, controlled trials are required to confirm the efficacy of these drugs on the incidence of fractures, particularly in long-term renal transplant patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant DK 067981-04 (A.D.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Weisinger JR, Carlini RG, Rojas E, et al. Bone disease after renal transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1300. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01510506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen A, Sambrook P, Shane E. Management of bone loss after organ transplantation. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1919. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham J. Pathogenesis and prevention of bone loss in patients who have kidney disease and receive long-term immunosuppression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:223. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham J. Posttransplantation bone disease. Transplantation. 2005;79:629. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000149698.79739.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffery JR, Leslie WD, Karpinski ME, et al. Prevalence and treatment of decreased bone density in renal transplant recipients: A randomized prospective trial of calcitriol versus alendronate. Transplantation. 2003;76:1498. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000092523.30277.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitterbauer C, Schwarz C, Haas M, et al. Effects of bisphosphonates on bone loss in the first year after renal transplantation—A meta-analysisof randomized controlled trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2275. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maalouf NM, Shane E. Osteoporosis after solid organ transplantation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2456. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grotz WH, Mundinger FA, Gugel B, et al. Bone fracture and osteodensitometry with dual energy x-ray absorptiometry in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1994;58:912. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199410270-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham J. Bisphosphonates in the renal patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1505. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cruz DN, Brickel HM, Wysolmerski JJ, et al. Treatment of osteoporosis and osteopenia in long-term renal transplant patients with alendronate. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:62. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coco M, Glicklich D, Faugere MC, et al. Prevention of bone loss in renal transplant recipients: A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous pamidronate. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2669. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000087092.53894.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pascual J, Torrealba J, Myers J, et al. Collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in a liver transplant recipient on alendronate. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1435. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munier A, Gras V, Andrejak M, et al. Zoledronic acid and renal toxicity: Data from French adverse effect reporting database. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1194. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw—Do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2278. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graham DY. What the gastroenterologist should know about the gastrointestinal safety profiles of bisphosphonates. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:1665. doi: 10.1023/a:1016495221567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strampel W, Emkey R, Civitelli R. Safety considerations with bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis. Drug Saf. 2007;30:755. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200730090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group. Lancet. 1996;348:1535. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotz WH, Rump LC, Niessen A, et al. Treatment of osteopenia and osteoporosis after kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:1004. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199810270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giannini S, D’Angelo A, Carraro G, et al. Alendronate prevents further bone loss in renal transplant recipients. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:2111. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.11.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Djamali A, Kendziorski C, Brazy PC, et al. Disease progression and outcomes in chronic kidney disease and renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1800. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kukla A, Adulla M, Pascual J, et al. CKD stage-to-stage progression in native and transplant kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:693. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durieux S, Mercadal L, Orcel P, et al. Bone mineral density and fracture prevalence in long-term kidney graft recipients. Transplantation. 2002;74:496. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Shaughnessy EA, Dahl DC, Smith CL, et al. Risk factors for fractures in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;74:362. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200208150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vautour LM, Melton LJ, III, Clarke BL, et al. Long-term fracture risk following renal transplantation: A population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:160. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1532-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiramatsu K, Asaba Y, Takeshita S, et al. Overexpression of gamma-glutamyltransferase in transgenic mice accelerates bone resorption and causes osteoporosis. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2708. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niida S, Kawahara M, Ishizuka Y, et al. Gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase stimulates receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand expression independent of its enzymatic activity and serves as a pathological bone-resorbing factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311905200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asaba Y, Hiramatsu K, Matsui Y, et al. Urinary gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) as a potential marker of bone resorption. Bone. 2006;39:1276. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorgensen L, Jenssen T, Ahmed L, et al. Albuminuria and risk of non-vertebral fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1379. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.13.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smavatkul C, Pascual J, Desai AG, et al. Disease progression and outcomes in type 1 diabetic kidney transplant recipients based on post-transplantation CKD staging. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:631. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]