Abstract

Aims: To assess the effectiveness and acceptability of a brief community-based educational program on changing the drinking pattern of alcohol in a rural community. Methods: A longitudinal cohort study was carried out in two rural villages in Sri Lanka. One randomly selected village received a community education program that utilized street dramas, poster campaigns, leaflets and individual and group discussions. The control village had no intervention during this period. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) was used to measure the drinking pattern before and at 6 and 24 months after the intervention in males over 18 years of age in both villages. The recall and the impact of various components of the intervention were assessed at 24 months post-intervention. Results: The intervention was associated with the development of an active community action group in the village and a significant reduction in illicit alcohol outlets. The drama component of the intervention had the highest level of recall and preference. Comparing the control and intervention villages, there were no significant difference between baseline drinking patterns and the AUDIT. There was a significant reduction in the AUDIT scores in the intervention village compared with the control at 6 and 24 months (P < 0.0001). Conclusions: A community-based education program had high acceptance and produces a reduction in alcohol use that was sustained for 2 years.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol consumption is a significant social and medical problem in rural Sri Lanka and in many parts of rural Asia. Alcohol-related cirrhosis and accidents are well documented in Sri Lankan hospital practice (Dissanayake and Navaratne, 1999; De Silva et al., 2008), as are high rates of alcohol-related injury, especially alcohol-related road traffic accidents (Hettige, 1993; Samarasinghe, 2006). In 2005, Census and Statistics Department in Sri Lanka reported a cirrhosis mortality rate of 33.4 per 100,000 males, among the highest in the world, which compares with 14.1 in the UK and 28.14 in France (Leon and McCambridge, 2006). Alcohol use is strongly linked with suicide attempts in Sri Lanka and the high incidence of deliberate self-harm (van der Hoek and Konradsen, 2005; Eddleston et al., 2006; Gunnell et al., 2007; Abeyasinghe and Gunnell, 2008). In terms of social and cultural deleterious impacts, alcohol is a major cause of domestic violence within families (Ramachandran, et al., 1986; Subramaniam and Sivayogan, 2001) and there is also a strong and complex relationship between poverty and alcohol use (Hettige, 1993; Gunasekera and Perera, 1997; Abeyasinghe, 2002; Samarasinghe, 2006).

In Sri Lanka, the per capita annual consumption of legally produced alcohol rose from 1.8 to 7.37 l between 1980 and 2003 (Social Conditions of Sri Lanka, 2010). The significance of the problem in Sri Lanka was actively acknowledged by the policy legislated in 2007 to reduce alcohol and tobacco use. This policy has not had the desired effect as the legal alcohol sales have increased after 4 years (Abeyasinghe, 2011). Estimates based on the legal alcohol significantly underestimate true consumption, as these estimates do not account for illegally produced alcohol (Rehm et al., 2009): in Sri Lankan rural and poor urban areas, the predominant alcohol consumed is illicitly produced ‘kassipu’, which is cheaper because it avoids the tax and is unregulated. The consumption of kassipu also has additional, well-reported risks identified such as inadvertent production of highly toxic methanol and deliberate adulteration with various pesticides (Dias, 2010). With the exception of plantation workers and some fishing communities, alcohol use in Sri Lanka almost exclusively occurs in men, predominately in a pattern of binge drinking (Abeyasinghe, 2002).

To date most of the evidence for cost-effective interventions only exists in well-regulated high-income countries (Ezzati et al., 2002; Anderson et al., 2009; Beaglehole and Bonita, 2009; Rehm et al., 2009). Current legislative approaches to alcohol control in Sri Lanka are overseen by the National Alcohol Authority and include restriction of licensed sales of taxed alcohol to adults over 21 years of age, restriction of sales on certain religious holidays, banning of any advertising, sports sponsorship and no free distribution of alcohol at events. However, these approaches to restrict harm are largely circumvented by the high community use of illicit alcohol. Thus community-based public health interventions are required to complement existing regulation to reduce alcohol-related harm in the community (Holder, 2005). While NGOs report some success in reducing alcohol use and harms in highly restricted Sri Lankan communities such as among plantation workers (http://www.adicsrilanka.org), these interventions are rarely evaluated with a sufficient methodological rigueur and there is no evaluated work done in less regulated rural communities that are typical in Asia.

This study reports the findings of a pilot study that examined the acceptance and effectiveness of a multi-component community-based alcohol educational program in a rural Sri Lankan village.

METHODS

Ethical considerations

The research was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. The village agreed to alcohol education interventions. Consent was taken from individuals for interviews. Attendance and subsequent advice at the baseline medical clinic was free.

Design

The two rural villages are separated by a distance of 15 km and of comparable size, population and socio-economic backgrounds were selected. These villages were in separate local government divisions of the central province of Sri Lanka. The villages were selected based upon the information elicited from interviews with police officers, government servants and community leaders of the two divisions, showing that these two villages had a higher prevalence of illicit distilleries and higher consumption of alcohol than other villages in the divisions.

One village was subsequently randomly selected (by flipping a coin) to receive a multi-component educational intervention program and the other village served as the control.

Study population

Before the study formally started, the first author with the villages' permission lived in both villages for 5 months and participated in village life to develop a relationship with the villagers, to understand their needs and to facilitate the follow-up. All males within the age range of 18–80 years residing in the villages were included as subjects of the study on alcohol consumption. However, males who were temporary residents or who worked outside of the village were excluded from the study at baseline due to anticipated difficulties in the follow-up (Fig. 1). Most males have left secondary school by the age of 19 and the legal age for alcohol consumption is 21 years. At the follow-up, additional focus groups and interviews were held with 23 adult women and four community leaders in the intervention village.

Fig. 1.

The description of male study population exclusions and lost to study the follow-up described by their baseline audit status.

Intervention

The main objective of this intervention program was to educate the community about low-risk drinking (less than the equivalent of three standard drinks/day) and to highlight the benefits of restricting amounts of drinking.

The intervention village received a community education program on the basis of possible consequences for individuals, families and society from alcohol misuse and emphasized the positive gains that could accrue from reducing consumption. The concept of a unit of alcohol and how it was relevant to the types of alcohol being locally consumed was introduced to the community. The multi-component education program was delivered over a 3-month period and comprised a series of traditionally based street dramas in conjunction with poster campaigns, leaflets and brief individual and group discussions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Timing of the planned community interventions

| Intervention sequence | |

|---|---|

| Time 0 | Poster Campaign 1 |

| Week 1 | Drama |

| Week 3 | Poster Campaign 2 & Pamphlet |

| Week 5 | Drama |

| Week 9 | Drama |

| Week 13 | Drama |

At week 10 and week 15, the villagers spontaneously created and performed their own drama production.

From week three–nine the researcher conducted brief interventions (between 15 and 45 min) with all dependent drinkers emphasizing a reduction in intake or switch to licensed alcohol.

Street drama

The creation, preparation and a performance for the street drama were by the Department of Fine Arts under the supervision of the Department of the Psychiatry, the University of Peradeniya. These four separate dramas presented information showing the negative consequences for an individual, family and society as the result of drinking alcohol and how these could be reversed and positive results could be obtained by moderating-drinking. While the drama is popular in Sri Lanka, drama-based education had not been used in this context before. To maximize the likelihood of high community attendance, the dramas were performed on government holidays and in the evening when most of the village was home. Each performance was preceded by the actors moving through the village dancing, singing and leading the community to the village communal area. Drama performances in the village were recorded on video for thematic analysis and CD copies were produced and subsequently distributed in the village.

Poster campaign

A poster campaign was delivered in the colloquial language that highlighted how negative consequences to the human body, economy and society could be overcome by moderating one's drinking. The poster design and font were done in a locally familiar style that is used for important community events such as festivals. These posters were placed in commonly frequented areas of the villages.

Leaflet

The leaflet focused upon alcohol-drinking patterns, its consequences and when people should seek medical advice. It defined alcohol dependence as a disease and emphasized safe levels of alcohol consumption and avoidance of high-concentration alcoholic beverages such as kasippu. Leaflets were hand delivered to each household.

Brief interventions

At baseline, a free medical clinic was held in each village on a public holiday to increase access. Partly as an incentive for the attendance blood was taken for liver function tests, creatinine and blood sugar, these results were supplied to the individuals’ normal health care provider. Individuals who were identified as high-risk drinkers received a brief intervention given by the attending doctor. Subsequently in the intervention village drinkers whose Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) score placed them in either the harmful or dependent category were offered a single brief intervention directed at harm minimization and safer drinking patterns by the first author.

Outcome measures

The quantitative analysis of drinking patterns used the World Health Organization developed and culturally validated AUDIT questionnaire as a screening instrument for hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption (Saunders et al., 1993; Conigrave et al., 1995a, b). Unblinded trained interviewers administered the AUDIT questionnaire in both the control and intervention villages at baseline and at 6 and 24 months after the intervention.

The AUDIT was administered at baseline as part of the free medical clinic that was run in each village. Men who were not available on that day were subsequently approached at a time convenient to them. All men over 18 were identified in the villages and interviewed at baseline with subsequent drops outs and exclusion described in Fig. 1. The follow-up of subjects at 6 and 24 months post intervention was undertaken by trained interviewers who made repeated visits to the village over a period of 2 months to complete the follow-up AUDIT scores. An average 20–25 min was allocated for administering the questionnaire for each person during the course of this study.

The additional follow-up at 24 months in the intervention village included: the quantitative recall of interventions measured by the questionnaire, community-response to and preference of interventions was explored using focus group discussions facilitated by post-graduate sociologists. Interviews were transcribed and subject to thematic analysis. The community response to alcohol use was measured by quantitative questionnaire-based interviews and focus group discussions at baseline and at the follow-up. Sources of alcohol supply in each village were ascertained during these interviews.

Analyses

Statistical analysis was done in Prism 5.03 for Mac GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA, www.graphpad.com. The primary analysis was of the study populations AUDIT score at baseline and then the differences in scores compared with the individual's baseline at 6 months and at 24 months with Mann–Whitney test. An analysis of covariance was done on the linear regression lines that plotted the change in individual's scores compared with their baseline scores. The differences in the proportion of subjects in each AUDIT category were calculated in OpenEpi and expressed as Mid-P exact. (Dean AG, Sullivan KM, Soe MM. OpenEpi: Open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version 2.3.1. www.OpenEpi.com, updated 2011/23/06, accessed 201207/16.)

RESULTS

Baseline comparisons showed similar demographics between the intervention and the control community (148 families comprising 121 men aged at least 18 years in the intervention community, compared with 130 families comprising 125 men aged at least 18 years in the control community). In both communities, 50% of males earned less than $150 per month and none earned more than $250 per month, and drinking patterns in both villages were similar (Table 2). At baseline, there were 155 males in the intervention village and 135 males in the control village. There were 34 exclusions in the intervention village and 10 in the control village, exclusions were either temporary residents or working outside the village (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Basic demographic data on study population

| Intervention village (%) | Control village (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Village size | ||

| Education level | 0.32 km2 | 0.36 km2 |

| No formal education | 4.13 | 2.4 |

| Grade 1–5 | 27.27 | 29.6 |

| Up to O/L | 56.19 | 60.8 |

| Up to A/L | 12.39 | 7.2 |

| Income level | ||

| Rs 0–4999 | 9.1 | 8.8 |

| Rs 5000–14,999 | 46.2 | 60.8 |

| Rs 15,000–24,999 | 41.3 | 34.4 |

| Rs ≥ 25,000 | 3.3 | 0.0 |

| Age level | ||

| 18–24 | 16.5 | 12 |

| 25–30 | 14.1 | 12 |

| 31–40 | 15.7 | 25.6 |

| 41–50 | 22.3 | 23.2 |

| 51–60 | 20.6 | 14.4 |

| 61–70 | 4.9 | 6.4 |

| 71–80 | 5.7 | 6.4 |

| Employment structure | ||

| Casual labor | 48.8 | 57.6 |

| Driving | 9.1 | 3.2 |

| Farming | 6.6 | 7.2 |

| Hair cutting | 5.0 | 0.8 |

| Carpenter/mason | 6.6 | 12.8 |

| Small business | 7.4 | 8.0 |

| Government employed | 8.3 | 4.0 |

| Unemployed | 8.3 | 6.4 |

There was a complete follow-up for AUDIT scores at 6 months; all the missing records were deaths. The 24-month follow-up had not been originally planned. When further funds had become available, the 24 months was conducted in a limited time frame that did not allow the complete follow-up of agricultural workers (missing follow-up: 9% intervention, 16% in control groups). The baseline AUDIT characteristics of those missed at follow-up are shown in Fig. 1.

Post intervention changes occurred in three domains

Community response to alcohol use

In the intervention village (but not the control), a community action group had spontaneously formed by the time of the 6-month follow-up and remained active at 24 months. By direct action and lobbying local police, the group had closed down two of the three illicit alcohol outlets within the first 6 months and all outlets by 24 months. (Table 3) They had also destroyed any stores of illicit alcohol that they found in the jungle. This was reflected in a significant reduction in illicit alcohol consumption in the intervention village and an overall reduction in the amount of alcohol consumed. Interviews at 24 months revealed a shift to legal alcohol; typically, this was bought from a town back to the village where a bottle was resold in smaller portions.

Table 3.

Drinking pattern in the intervention and control villages.

| Intervention village* |

Control village |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE (n = 121) | 6 months (n = 117) | 24 months (n = 103) | PRE (n = 125) | 6 months (n = 124) | 24 months (n = 99) | |

| Level of drinking AUDIT* | ||||||

| Low-risk (0–7) | 33.1 (40) P = 0.97 | 53.8 (63) P = 0.0002 | 46.6 (48) P = 0.0005 | 32.8 (41) | 29.8 (37) | 23.5 (23) |

| Hazardous (8–15) | 29.8 (36) P = 0.98 | 26.5 (31) P = 0.06 | 38.8 (40) P = 0.8 | 29.6 (37) | 37.9 (47) | 40.8 (40) |

| Harmful (16–19) | 21.5 (26) P = 0.98 | 12.0 (14) P = 0.09 | 8.7 (9) P = 0.003 | 21.6 (27) | 20.2 (25) | 24.5 (24) |

| Dependent >20 | 15.7 (19) P = 0.95 | 7.7 (9) P = 0.26 | 5.8 (6) P = 0.2 | 16.0 (20) | 12.1 (15) | 11.2 (11) |

| Drinking frequency | ||||||

| No alcohol | 17.4 (21) | 26.5 (31) | 22.3 (23) | 18.4 (23) | 15.3 (19) | 14.1 (14) |

| Monthly or less | 15.7 (19) | 36.8 (43) | 35.0 (36) | 30.4 (38) | 29.8 (37) | 24.2 (24) |

| 2–4 times/month | 29.8 (36) | 23.1 (27) | 25.2 (26) | 16.0 (20) | 25.8 (32) | 29.3 (29) |

| 2–3 times a week | 10.7 (13) | 12.0 (14) | 16.5 (17) | 15.2 (19) | 15.3 (19) | 21.2 (21) |

| ≥4 times a week | 26.4 (32) | 1.7 (2) | 1.0 (1) | 20.0 (25) | 13.7 (17) | 11.1 (11) |

| Drinking volume | ||||||

| No alcohol | 17.4 (21) | 26.5 (31) | 22.3 (23) | 18.4 (23) | (15.3) 19 | (14.1) 14 |

| 1–4 units | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14.6 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 or 6 units | 12.4 (15) | 18.8 (22) | 30.1 (31) | 7.2 (9) | 8.1 (10) | 8.1 (8) |

| 7–9 units | 24.8 (30) | 31.6 (37) | 16.5 (17) | 29.6 (37) | 33.1 (41) | 35.4 (35) |

| ≥10 units | 45.5 (55) | 23.1 (27) | 16.5 (17) | 44.8 (56) | 43.5 (54) | 42.4 (42) |

| Type of alcohol | ||||||

| Kasippu | 50.4 (61) | 11.1 (13) | 0 | 57.6 (72) | 52.4 (65) | 32.3 (32) |

| Arrack | 24.0 (29) | 50.4 (59) | 59.2 (61) | 20.0 (25) | 26.6 (33) | 33.3 (33) |

| Beer | 7.4 (9) | 11.1 (13) | 18.4 (19) | 4.0 (5) | 5.6 (7) | 5.1 (5) |

| Toddy | 0.8 (1) | 0.9 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 15.2 (15) |

| Nil | 17.4 (21) | 26.5 (31) | 22.3 (23) | 18.4 (23) | 19 (15.3) | 14.1 (14) |

*P-values are calculated for comparison of intervention with control village.

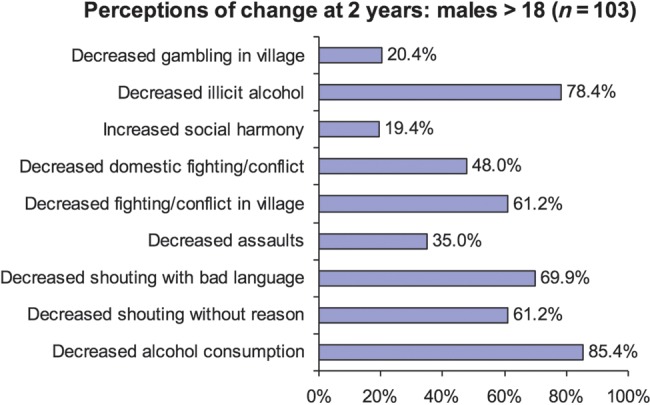

Males in the intervention village perceived that there was less alcohol consumption in their community, less illicitly produced alcohol was available and decreased shouting and bad language, shouting without a reason, and fighting or conflict in the community (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mens' perceptions of changes in behavior within the intervention village.

Community response to the interventions

The recall of the intervention was very high for the baseline medical clinic (93%), street drama (85%) and poster (75%), whereas the leaflets (43%) and brief intervention (52%) were less well-recalled. The preferred intervention by the community was the street drama with 75% approval with the other interventions being <15%. This preference was reflected in that the villagers initiated two additional dramas during the intervention period (weeks 10 and 15), their own street drama was based around the original intervention themes. The village was supplied with a DVD of the original performances at the end of the intervention programme; this DVD was watched by 52% of the villagers within the follow-up period.

Quantitative analysis of drinking patterns

At baseline, the predominant and comparable drinking pattern in both villages was binge drinking (periodic drinking to intoxication) with >50% of villagers consuming illicit alcohol (Table 3). There was no difference between the intervention and control village in the population baseline AUDIT scores (Fig. 2) or in the proportions of population in each AUDIT category.

Fig. 2.

The comparison of baseline median AUDIT scores with interquartile ranges in both the intervention and control villages. There is no statistical difference, P = 0.95 (Mann–Whitney).

There was a significant reduction in AUDIT scores in the intervention versus control communities P < 0.001 (Mann–Whitney) at both 6 and 24 months (Fig. 3), which was associated with the intervention village having a significantly higher proportion of subjects being in the low-risk AUDIT category at 6 and 24 months (Table 3). It can be seen from the plots of the extent of change in an individual's score against their baseline AUDIT score (Fig. 4) that this shift occurred across all audit categories and was significantly greater in the intervention village P < 0.0001 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Box plot of the differences in individuals' AUDIT scores from baseline at 6 and 24 months. Plotted as median, IQR and range.

Fig. 4.

Linear regression plot of the change in an individual's AUDIT score against their baseline score.

The intervention village demonstrated a sustained reduction in alcohol use with less-frequent drinking and lower volumes of alcohol consumed per occasion at 6 and 24 months (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This community-based intervention was associated with evidence of high community acceptance and this was associated significant sustained change in drinking pattern in the intervention village. Achieving such a high-level of the community involvement appeared to be a major a driver of most of the changes seen in the intervention village such that future studies exploring this approach should assume a high intracluster correlation coefficient.

The street drama had both high-recall and the community preference. This was distinguished from other components of the intervention by high levels of community participation as an audience and then subsequently as participants. The early initiation of locally produced drama was a strong indication of the cultural acceptance of this intervention and is supported by the subsequent viewing of video by village members. Equally surprising and undoubtedly significant was the spontaneous formation of a community action group. Women had a significant role in the community action group. The formation of such a group was not a part of the educational intervention message but may have been stimulated by the creation of community-based events. The community group advocacy for the subsequent closure of illicit alcohol distribution was associated with a shift to drinking smaller quantities of legal alcohol. This shift to legal alcohol consumption effectively brings the alcohol consumption back into the influence of the existing regulatory and taxation framework. The brief intervention delivered at the time of the medical clinic did not appear to have any appreciable effect in the control village. In the intervention village, other intervention components may have had an additive or synergistic effect despite the lower recall or preference.

In the intervention village, there was a significant increase in AUDIT-defined low-risk drinking and a reduction in harmful and dependent drinking. The reduction in harmful and dependent drinking shifted subjects into the hazardous drinking strata (increased risk of harmful consequences for the drinker without having yet caused any alcohol-related harm) when compared with both baseline and the control village. In contrast the control village showed an increase in hazardous drinking, which was contributed to by a shift from low-risk drinking (Fig. 4). This occurred even in the presence of higher number of hazardous drinkers who were lost to follow-up in the control village. These findings are mirrored by decreased weekly frequency of drinking and unit consumption at the time of drinking seen in the intervention village. (Table 3) Regardless of the reasons for an increase of hazardous drinking, this particular strata requires further investigation as it may benefit from interventions that are more directed towards binge drinking. This education intervention did not specifically target hazardous drinking; it focused mainly on harmful drinking. Future research should target and evaluate interventions that address the different drinking patterns within the community.

Community-level interventions that generally combine individual and environmental change strategies have been shown to be successful and have the capacity to achieve significant reductions in alcohol consumption and harms, independently of regulatory change (Wagenaar et al., 2000; Wandersman and Florin, 2003). Such interventions have potential for relatively large benefits at a population level (Sorensen et al., 1998) and could be particularly important in contexts where much of the alcohol consumed is outside any regulatory framework.

One of the most surprising results was the reduction of proportion of alcohol-dependent subjects in the intervention village but not in the control village (Table 3). This is unlikely to be solely explained by direct alcohol education as we mainly targeted the harmful drinkers in the belief that they would be the ones to benefit the most. This change in dependent drinkers is likely to have been influenced by the powerful community forces that our intervention unleashed. The effectiveness of this community action was demonstrated by the complete disappearance of illegal Kasippu drinking and the increase of consumption of legal spirits and beer in the intervention village. To the best of our knowledge such an effect on alcohol dependence from the community action that has been sustained for 24 months described before.

In Sri Lanka, most health education programs with regard to smoking and drinking emphasize the negative outcomes of such behavior (loss framed). Within this context the intervention village was given a message regarding alcohol that was unique and untried in Sri Lanka before. The message was to cut-down on harmful and dependent patterns of drinking to gain physical, emotional, family and other benefits. This message was quite different from the ongoing message both communities were exposed to thorough Buddhist temples, media and the state: that of total elimination of drinking through abstinence. The ethics review raised concerns that our message of promoting moderate drinking would lead to more drinking in the village. However, the results indicate that such gain-framed message has led to overall reduction in drinking in the intervention village. The promotion of abstinence is arguably initially an unrealistic aim for a community with high-alcohol use and may hinder engagement with drinkers.

Alcohol is a leading cause of medical and social morbidity in Sri Lanka, and this is also true for many other parts of rural Asia. Significant reductions in alcohol use have been shown to have benefits in reducing harm to the health and social well-being as well as a reduction in poverty. As alcohol consumption is higher in more economically developed regions, it is likely that alcohol consumption in countries like Sri Lanka will continue to rise as they become more economically developed (WHO, 2004). Given the evidence for the effectiveness of early interventions in other areas of public health (Heymann, 2008), it is important to develop culturally appropriate effective intervention strategies.

There are a number of limitations to be considered in this study. The exact concentration of alcohol in ‘Kassipu’ is variable, typically 40% at the manufacture but often diluted; therefore, we assumed a concentration of 20% in our calculations for the AUDIT score. We chose villages where there was information that alcohol use was high: this may have provided an environment that was more amenable to the formation of a community action group than a village with lower alcohol prevalence. A major limitation of this pilot study is that with a significant cluster effect it is underpowered to definitely demonstrate a reduction in higher risk drinking. The first author was also well-known in both villages; this may not be easily replicable. Any influence that might have had on the follow-up responses seems unlikely to have been significantly stronger in one village than the other. The cluster effect in this example is very likely to be due to the community's engagement, which suggests that the intervention as a whole and drama in particular had high cultural acceptability. If this intervention is generalizable, it would have a great relevance for other marginalized communities in rural Asia. As the successful community intervention is dependent on social cohesion and leadership, future interventions need to explore strengthening existing intra-community networks. As much of the results were dependent upon this occurring, these results might not be generalized to less-cohesive communities. Further research is required to explore the generalizability of this study; it might also explore health outcomes related to reduction in alcohol use.

CONCLUSION

A brief community-based positively framed alcohol education program had high community acceptance. The evidence of effectiveness in this pilot project needs to be confirmed by a more extensive trial before recommending the approach is adopted routinely.

Funding

This study was supported by the South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, which is funded by the Wellcome Trust/National Health and Medical Research Council International Collaborative Research Grant GR071669MA. The study sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the Wellcome Trust.

Conflict of interest statement. The Authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Abeyasinghe R. Illicit Alcohol. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyasinghe R. Towards an evidence based alcohol policy. Sri Lanka J Psychiat. 2011;2:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyasinghe R, Gunnell D. Psychological autopsy study of suicide in three rural and semi-rural districts of Sri Lanka. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43:280–5. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0307-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet. 2009;373:2234–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaglehole R, Bonita R. Alcohol: a global health priority. Lancet. 2009;373:2173–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB. The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Alcohol use disorder identification test. Addiction. 1995a;90:1349–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901013496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigrave KM, Saunders JB, Reznik RB. Predictive capacity of the AUDIT questionnaire for alcohol-related harm. Addiction. 1995b;90:1479–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901114796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva P, Jayawardana P, Pathmeswaran A. Concurrent validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:49–50. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias RS. Paraquat used as a catalyst to increase the percentage of alcohol distillated in illicit brewing industry of Sri Lanka. J Brew Distil. 2010;1:22–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayake P, Navaratne NM. 24% of male deaths alcohol related. Ceylon Med J. 1999;44:40–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Sudarshan K, Senthilkumaran M, et al. Patterns of hospital transfer for self-poisoned patients in rural Sri Lanka: Implications for estimating the incidence of self-poisoning in the developing world. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84:276–82. doi: 10.2471/blt.05.025379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, et al. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360:1347–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera R, Perera MRC. Assessing the Impact of Drug Use on Programmes for Alleviating Poverty: Survey report. Sober Sri Lanka: Colombo; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D, Fernando R, Hewagama M, et al. The impact of pesticide regulations on suicide in Sri Lanka. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1235–42. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettige S. Alcoholism, poverty and health in rural Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J Agrari Stud. 1993;8:27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann DL. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. 19th edn. Washington: American Public Health Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Holder H. The public policy importance of the northern territory's living with alcohol program, 1992–2002. Addiction. 2005;100:1571–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon DA, McCambridge J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950 to 2002: an analysis of routine data. Lancet. 2006;367:52–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67924-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran S, Lahie YKM, Herath CA, et al. Recent aspects of alcoholism in Sri Lanka—an increasing health hazard. Alcohol Alcohol. 1986;21:397–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarasinghe D. Sri Lanka: alcohol now and then. Addiction. 2006;101:26–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, et al. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-ii. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Social Conditions of Sri Lanka. Department of Census and Statistics Sri Lanka. http://www.statistics.gov.lk/social/social%20conditions.pdf. 20 December 2010, date last retrieved.

- Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, et al. Implications of the results of community intervention trials. Ann Rev Pub Hlth. 1998;19:379–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam P, Sivayogan S. The prevalence and pattern of wife beating in the Trincomalee district in eastern Sri Lanka. SE Asian J Trop Med. 2001;32:186–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoek W, Konradsen F. Risk factors for acute pesticide poisoning in Sri Lanka. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:589–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Murray DM, Gehan JP, et al. Communities mobilizing for change on alcohol: outcomes from a randomized community trial. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:85–94. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandersman A, Florin P. Community interventions and effective prevention. Am Psychol. 2003;58:441–8. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global status report on alcohol 2004. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2004. [Google Scholar]