Abstract

Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) causes an economically significant disease of chickens worldwide. Very virulent IBDV (vvIBDV) strains have emerged and induce as much as 60% mortality. The molecular basis for vvIBDV pathogenicity is not understood, and the relative contributions of the two genome segments, A and B, to this phenomenon are not known. Isolate 94432 has been shown previously to be genetically related to vvIBDVs but exhibits atypical antigenicity and does not cause mortality. Here the full-length genome of 94432 was determined, and a reverse genetics system was established. The molecular clone was rescued and exhibited the same antigenicity and reduced pathogenicity as isolate 94432. Genetically modified viruses derived from 94432, whose vvIBDV consensus nucleotide sequence was restored in segment A and/or B, were produced, and their pathogenicity was assessed in specific-pathogen-free chickens. We found that a valine (position 321) that modifies the most exposed part of the capsid protein VP2 critically modified the antigenicity and partially reduced the pathogenicity of 94432. However, a threonine (position 276) located in the finger domain of the virus polymerase (VP1) contributed even more significantly to attenuation. This threonine is partially exposed in a hydrophobic groove on the VP1 surface, suggesting possible interactions between VP1 and another, as yet unidentified molecule at this amino acid position. The restored vvIBDV-like pathogenicity was associated with increased replication and lesions in the thymus and spleen. These results demonstrate that both genome segments influence vvIBDV pathogenicity and may provide new targets for the attenuation of vvIBDVs.

INTRODUCTION

Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) of chickens (Gallus gallus) is one of the most economically significant viruses of poultry worldwide. Serotype 1 IBDV strains infect B lymphocytes in the bursae of Fabricius (BF) of young chickens, inducing infectious bursal disease (IBD) which causes immunosuppression and sometimes mortality (1). Since 1987, very virulent IBDV (vvIBDV) strains have emerged and spread worldwide (2). Clinical signs caused by vvIBDV infection occur from 2 days postinfection (DPI) and typically include ruffled feathers, severe prostration, diarrhea, dehydration, and as much as 60% mortality (1). Intense inflammatory damage is caused in the BF as a result of the activation of T lymphocytes (3) and mast cells (4). This results macroscopically in bursal hypertrophy with edema and hemorrhages and microscopically in severe inflammation and depletion of the lymphoid follicles in the BF during the first 4 DPI, followed by atrophy of the organ (5). Different types of vaccines have been developed to prevent IBD, but no efficient method of treating the disease exists yet (6).

IBDV is a member of the family Birnaviridae, genus Avibirnavirus (7). The virus has a bisegmented double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) genome. Genome segment A (3.2 kbp) encodes a precursor polyprotein that is autocatalytically cleaved into proteins pVP2 (which subsequently matures into VP2), VP4, and VP3 (8). VP2 is the capsid protein and carries the major immunogenic determinants (9, 10). Its 3-dimensional structure has been described previously (11). VP4 is the virus protease (12, 13), responsible for the cleavage of the polyprotein. VP3 is a ribonucleoprotein and scaffolding protein (14–18). In a preceding, much shorter, and partially overlapping open reading frame (ORF), segment A also encodes the nonstructural protein VP5 (19), which is involved in virus release (20) and apoptosis (21, 22). Genomic segment B (2.8 kbp) encodes the virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) VP1 (23, 24). Its crystal structure and activation mechanism have been described previously (25). VP1 exists in the virus particle both as a free protein and as a genome-linked protein (26); it interacts with the viral genome (26, 27) and the carboxy-terminal region of VP3 (18, 28).

The antigenicity and pathogenicity of IBDV strains differ extensively. Although some progress has been made in understanding the molecular biology of IBDV, especially since a reverse genetics system has been available (29), the molecular basis for the increased pathogenicity of vvIBDV is still not fully understood.

Reverse genetics studies have shown that genome segment A provides the main basis for the bursal tropism of serotype 1 IBDV (30) and for IBDV pathogenicity. Indeed, the VP2-encoding region of a typical vvIBDV, expressed in the genetic context of a mildly virulent cell culture-adapted IBDV recipient strain, conferred the ability to induce severe bursal lesions (31). In addition, the alteration of VP2 amino acids (aa) 253, 279, and/or 284 of a vvIBDV strain by reverse genetics conferred adaptation to chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEF) (32–34). The resulting viruses proved to be attenuated for chickens (34, 35), but reversion mutations were observed upon passage in chickens and could restore virulence (36).

VP2 is, however, unlikely to be the only factor for virulence: laboratory-engineered reassortant viruses derived from vvIBDV exhibited delayed replication in the bursa (37) or failed to induce morbidity and mortality (31) unless they also had a typical vvIBDV-related segment B. This observation is consistent with the phylogeny-based hypothesis that both genome segments may be involved in the emergence of vvIBDV (38, 39). Recently, this hypothesis was substantiated by the isolation of three naturally occurring segment B-reassorted vvIBDV isolates, all with reduced pathogenicity in chickens (40, 41). Another recent experimental study based on reverse genetics demonstrated that several domains of the IBDV polymerase may contribute to virulence (42). Taken together, these findings suggest that mechanisms involving both segment A- and segment B-encoded proteins may be responsible for vvIBDV pathogenicity.

IBDV strain 94432 was originally identified as having both genome segments phylogenetically related to vvIBDVs (41, 43) and exhibiting atypical antigenicity (44), most probably based on one amino acid change in the variable antigenic domain of VP2 (43). In this paper we confirm unpublished previous observations that 94432 replicates extensively in the BF but induces only mild clinical signs and does not cause mortality, thus exhibiting a clear discrepancy between its vvIBDV-related genotype and its mildly pathogenic phenotype. Furthermore, we used reverse genetics as described by Mundt and Vakharia (29) to produce a molecular clone of 94432 with the same phenotype as its parent strain. By use of site-directed mutagenesis, the vvIBDV consensus nucleotide sequence was restored in different regions of 94432 genome segments A and/or B. The recombinant viruses were rescued and were tested for virulence under standardized experimental conditions. This in vivo study identified two amino acid changes critical for the reduced pathogenicity of isolate 94432, one at position 321 in the PHI loop of the VP2 projection domain (11) and the other at amino acid position 276 in VP1, located in the “finger” subdomain (25, 45). These findings experimentally demonstrate that both genome segments A and B contribute to vvIBDV virulence, and they may provide new targets for vvIBDV attenuation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All experiments were performed in agreement with national regulations on animal welfare and animal experiments, according to authorizations no. 22-4 and B-22-745-1 by the Prefecture des Cotes-d'Armor, France. The rescue and in vivo characterization of recombinant IBDVs (see below) were performed according to authorization no. 3569 CA-I by the French Commission for Genetically Modified Organisms. Experimental protocols for specific-pathogen-free (SPF) chickens were approved by the ethical committee of our institution (ComEth Afssa/ENVA/UPEC) under references 10-0007 and 10-0024.

Viruses and titrations.

The origins of strains 94432 (43, 46), F52/70 (47), BD3 (48), and 89163 (49) have been reported previously. Virus suspensions were prepared from the BF of inoculated chickens as described previously (49). Virus suspensions were titrated in 10-day-old SPF hen eggs (Anses-Ploufragan) (10-fold dilutions; 0.1 ml per egg; chorioallantoic membrane route; 7 eggs per dilution). Titers are expressed in median embryo infectious doses (EID50) (50).

Cells and chickens.

Transfection experiments were performed with CEF derived from SPF hen eggs (Anses-Ploufragan). All animal experiments were performed with 6-week-old SPF White Leghorn chickens (Anses-Ploufragan) housed in filtered-air, negative-pressure isolation units.

Sequencing of full-length segments A and B of IBDV strain 94432.

Viral RNA was extracted from infected BF as described previously (43). The complete nucleotide sequences of segments A and B were determined by sequencing of overlapping reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) products as described previously (41) and by rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (5′ RACE; Invitrogen) (42, 51).

Construction of full-length cDNA clones of 94432 segments A and B.

cDNA copies of segments A and B were produced by RT using sense primers complementary to the 3′ ends of their noncoding strands. (All primer sequences used in this study are available upon request.) The two sense primers contained 5′ extensions carrying the T7 promoter and a restriction site required for subsequent cloning of the PCR products. The resulting cDNAs were amplified by PCR using the same sense and antisense primers (sequence determined by 5′ RACE in 94432, with a 5′ extension containing the restriction sites required for subsequent cloning and linearization). The purified PCR products were cloned into the pUC18 vector. The resulting plasmids, designated pA94 and pB94 for segments A and B, respectively, were transformed into Escherichia coli, purified, and sequenced on both strands as described above. The sequences of pA94 and pB94 were corrected by site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) until they perfectly matched those of the BF-propagated 94432 virus.

Construction of recombinant IBDV segments A and B by site-directed mutagenesis.

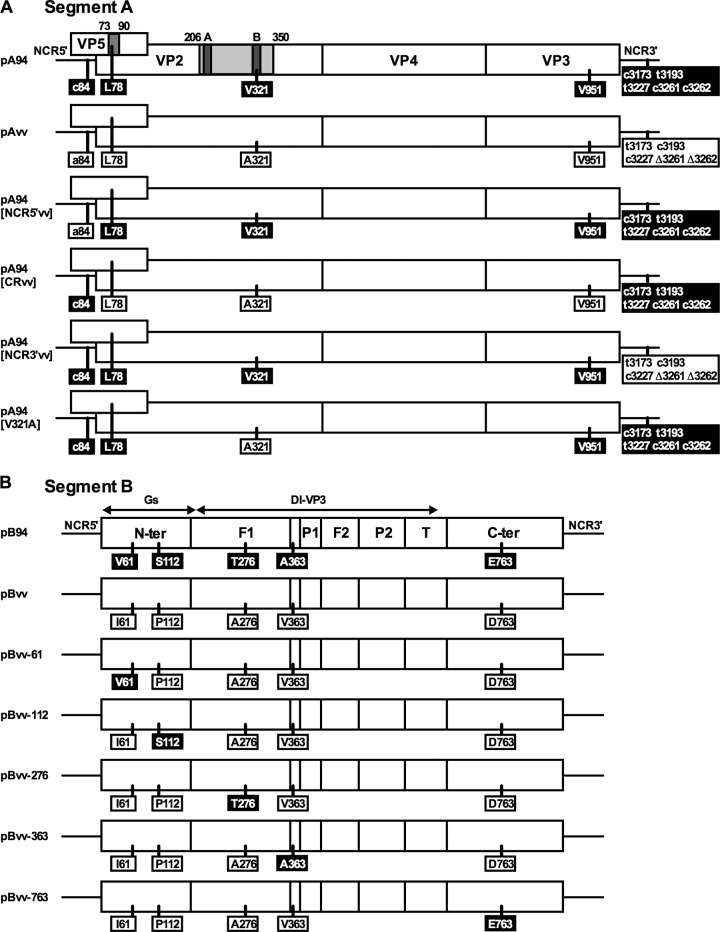

Table 1 presents the locations of genetic changes in segments A and B of 94432 compared with the noncoding regions (NCRs) of vvIBDV strain D6948 or the consensus coding region of vvIBDV strains D6948, HK46, BD3, and UK661 (accession numbers as shown in Table 1 footnote). Changes introduced into pA94 by site-directed mutagenesis resulted in five new constructs (Fig. 1A), with the vvIBDV genotype restored in either (i) the entire genome segment A (9 mutations; plasmid pAvv), (ii) the 5′ NCR only (1 mutation; plasmid pA94[NCR5′vv]), (iii) the coding region (CR) only (3 mutations; plasmid pA94[CRvv]), (iv) the 3′ NCR only (5 mutations; plasmid pA94[NCR3′vv]), or (v) the VP2 protein only (1 mutation; plasmid pA94[V321A]). Likewise, changes introduced into pB94 resulted in a “vvIBDV-like” B plasmid (pB94vv) and in five mutated derivatives of plasmid pB94vv, each retaining 1 aa typical of 94432. These plasmids were identified as pBvv-61, pBvv-112, pBvv-276, pBvv-363, and pBvv-763, depending on which of the 94432-like amino acids was retained (aa 61, 112, 276, 363, or 763) (Fig. 1B). The complete sequences of all plasmids were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing in both directions.

Table 1.

Nucleotide and amino acid differences between 94432 and very virulent or attenuated IBDV strainsa

| nt or aa position | nt or aa in: |

Gene or region | Note | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vvIBDVs | 94432 | Attenuated strains | |||

| Segment A | |||||

| 84 | a | c | a | 5′ NCR | |

| 78 | F | L | I | VP5 | Located in the predicted transmembrane domain; L78 also found in vvIBDV strain UK661 |

| 321 | A | V | A | pVP2 | Located in the antigenic domain. Two antigenically variant North American strains exhibit E321. An atypical vvIBDV strain with extensive antigenic changes exhibits T321. |

| 951 | I | V | I | VP3 | V951 also found in vvIBDV strain UK661 |

| 3173 | u | c | u | 3′ NCR | |

| 3193 | c | u | c | ||

| 3227 | c | u | c | ||

| 3261 | c | u | |||

| 3262b | c | ||||

| Segment B | |||||

| 61 | I | V | V | VP1 coding region | Located in the self-guanylylation domain; S112 also found in the attenuated strain Cu-1 |

| 112 | P | S | P | ||

| 276 | A | T | A | Located in the domain of interaction with VP3; mutations unique to 94432 | |

| 363 | V | A | V | ||

| 763 | D | E | D | Mutation unique to 94432 | |

Nucleotide (lowercase letters) or amino acid (capital letters) differences in the noncoding or coding regions, respectively, of segments A and B of 94432, compared with the NCRs of the well-defined strain D6948 (the reference vvIBDV strain) or with the consensus coding region of typical vvIBDV strains D6948, HK46, BD3, and UK661 (accession no. AF240686 and AF240687, AF092943 and AF092944, AF362776 and AF362770, and X92760, and X92761, respectively). For each nucleotide or amino acid position where 94432 differs from the vvIBDV consensus, the nucleotides or amino acids present in segments A and B of attenuated cell culture-adapted IBDV strains P2, CEF94, and CT (accession no. X84034 and X84035, AF194428 and AF194429, and AJ310185 and AJ310186, respectively) are also indicated.

The presence of nt 3262 in segment A of 94432 was confirmed by 5′ RACE in 7 sequenced clones.

Fig 1.

Organization of IBDV segments A and B and construction of recombinant A and B segments derived from pA94 and pB94. Segments A and B of 94432 cloned into the pUC18 plasmid under the control of the T7 promoter were designated pA94 and pB94, respectively. The positions and identities of 94432 nucleotides (NCRs) or amino acids (coding region) that differentiate 94432 segments A and B from those of typical vvIBDVs are given in filled boxes below each segment map. (A) Segment A. The small ORF codes for VP5, the transmembrane domain (aa 73 to 90) of which is shaded. The large ORF codes for VP2, VP4, and VP3. The hypervariable domain of VP2 (aa 206 to 350) (light shading) contains two major hydrophilic domains (domains A and B) (dark shading). Changes introduced into pA94 resulted in five constructs. The positions and identities of the vvIBDV nucleotide(s) and/or amino acid(s) introduced are given in open boxes below each segment map. (B) Segment B. The first double-headed arrow shows the region where the self-guanylylation site (Gs) of IBDV RdRp is predicted to be positioned (72). The second double-headed arrow indicates the domain of VP1 interacting with VP3 (DI-VP3) (18). The 3-dimensional structure of the IBDV RdRp allowed us to determine that the polypeptide chain can be divided into an N-terminal domain (N-ter); the central polymerase domain, which contains the “finger” (F1 and F2), “palm” (P1 and P2), and “thumb” (T) subdomains; and a C-terminal domain (C-ter) (25, 45). Changes introduced into pB94 by site-directed mutagenesis resulted in a “vvIBDV-like” B plasmid (pBvv) and in five mutated derivatives of plasmid pBvv, each retaining 1 aa typical of 94432. The positions and identities of the vvIBDV amino acids introduced are given in open boxes below each segment map.

Rescue of infectious recombinant IBDVs.

In vitro synthesis of cRNA from the linearized plasmids, subsequent transfection of CEF with capped cRNAs, and rescue in chickens of infectious IBDV from the transfected cells were all performed as described previously (42). Table 2 presents the genetic makeup of the rescued recombinant viruses. The sequence of each rescued IBDV was checked for conformity with the expected construction by nucleotide sequencing.

Table 2.

Rescued viruses and summaries of the protocols of the five animal experimentsa

| Animal expt | Plasmid: |

Virus | No. of groups (chickens per group) | Age of chickens (wks) | Days of sampling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used for segment A | Used for segment B | |||||

| 1 | pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 | 3 (25) | 6 | 1, 4, 21 |

| — | — | BD3 | ||||

| — | — | 89163 | ||||

| 2 | pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 | 6 (20) | 6 | 4, 24 |

| — | — | 94432 | ||||

| pAvv | pB94 | AvvB94 | ||||

| pA94[NCR5′vv] | pB94 | A94[NCR5′vv]B94 | ||||

| pA94[CRvv] | pB94 | A94[CRvv]B94 | ||||

| pA94[NCR3′vv] | pB94 | A94[NCR3′vv]B94 | ||||

| 3 | pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 | 3 (20) | 6 | 1, 4, 21 |

| pAvv | pB94 | AvvB94 | ||||

| pA94[V321A] | pB94 | A94[V321A]B94 | ||||

| 4 | pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 | 3 (20) | 6 | 1, 4, 21 |

| pA94 | pB94 | A94Bvv | ||||

| pA94 | pBvv | AvvBvv | ||||

| 5 | pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 | 7 (25) | 6 | 1, 4, 21 |

| pAvv | pBvv | AvvBvv | ||||

| pAvv | pBvv-61 | AvvBvv-61 | ||||

| pAvv | pBvv-112 | AvvBvv-112 | ||||

| pAvv | pBvv-276 | AvvBvv-276 | ||||

| pAvv | pBvv-363 | AvvBvv-363 | ||||

| pAvv | pBvv-763 | AvvBvv-763 | ||||

| pA94 | pB94 | mc94432 rev | ||||

—, no plasmid used; field isolate.

Comparison of IBDV antigenic profiles.

The parent virus 94432 and its molecular copy mc94432 were characterized antigenically by using an antigen capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (AC-ELISA) as described previously. This test is based on a panel of eight IBDV-specific neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (Mabs) that detected at least six epitopes located in the VP2 hypervariable domain (43, 46, 52).

Animal experiments.

Five animal experiments were designed (Table 2) in order (i) to compare the pathogenicity of mc94432 with those of two representative vvIBDV strains and the parental virus 94432, (ii) to evaluate the importance of different regions of segment A in the reduced pathogenicity of 94432, (iii) to determine which amino acid(s) encoded by segment A is responsible for reduced pathogenicity, (iv) to evaluate the importance of segment B, or (v) to determine which amino acid(s) encoded by segment B is responsible for reduced pathogenicity. Table 2 shows which viruses were included in the individual experiments.

Briefly, at day 1, 6-week-old SPF chickens were weighed and were divided into groups of comparable sex and weight, 20 to 25 birds each. Individual chickens were identified by colored rings on their legs. The blood of at least 5 chickens per group was sampled to confirm seronegativity for IBDV. On the same day, each bird was inoculated intranasally with 105 EID50 of the challenge virus. All groups receiving infectious virus were housed in negative-pressure filtered-air isolators. All experiments included a mock-inoculated control group of comparable size, receiving phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) only and kept in a positive-pressure isolator.

Assessment of pathogenicity during the acute phase of the disease was based on (i) the intensity of clinical signs observed until 10 days postinfection (DPI), (ii) mortality rates, (iii) IBDV-induced bursal atrophy (as measured by the bursa-to-body weight [b/B] ratio), (iv) the severity of histological lesions (see below) in the BF (as well as in the thymus and spleen in experiments 2, 3, 4, and 5) at 1, 4, and 21 or 24 DPI, (v) serological responses at the ends of the experiments, and (vi) the virus load in the lymphoid organs sampled throughout the experiments. In addition, in experiments 4 and 5, bursal mastocytes were quantified by immunostaining at 4 DPI (see below).

Clinical signs were quantified using a newly developed symptomatic index (42). Briefly, scores on this index range from 0 to 3 with increasing severity, as follows: 0, “lack of signs”; 1, “typical IBD signs (ruffled feathers) conspicuous in quiet bird only, the bird stimulated by a sudden change in environment (light, noise, or vicinity of experiment observer) appears normal, motility is not reduced”; 2, “typical IBD signs conspicuous even when bird is stimulated, dehydration is apparent, motility may be slightly reduced”; 3, “typical severe IBD signs with prostration or death.” In all experiments, the mean symptomatic index (MSI) scores of the surviving chickens were calculated daily from 1 to 10 DPI. To ensure consistency in the evaluation of the symptomatic index, each score was determined independently by two previously trained observers. The results of the two observers were compared, and a consensus score was determined.

Histological examinations.

Histological examinations were performed by M. Lagadic (Maisons-Alfort, France). Histopathological damage in the BF was quantified by the bursal lesion score (BLS) according to Skeeles' scale (53), with five degrees, as follows: 0, no lesions; 1, mild (scattered cell depletion in a few follicles); 2, moderate (one-third to one-half of the follicles have atrophy or depletion of cells); 3, diffuse (atrophy of all follicles); 4, acute inflammation and acute necrosis typical of IBD. Thymic lesions were quantified based on two criteria: “lymphoid necrosis” and “depletion of lymphoid cells.” Spleen lesions were quantified similarly based on five criteria: “lymphoid necrosis,” “hyperplasia of macrophagic sheaths,” “sero-fibrinous exudate,” “necrosis of macrophages,” and “vacuolization of macrophages.” The score for each criterion ranged from 0 to 4 with increasing severity, so that thymus and spleen examinations resulted in compound thymic or spleen lesion scores (TLS or SLS, respectively) ranging from 0 to 8 or 0 to 20, respectively.

Mast cell immunostaining.

Mast cell examinations were performed by A. Fautrel (INSERM U620, H2P2 histopathology platform IFR140, Rennes, France). Changes in mast cell numbers in the BF were quantified at 4 DPI by staining using rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) that bind mast cell receptor CD117/c-kit. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and were embedded in paraffin. Serial 4-μm sections were prepared. Mast cells were stained with rabbit anti-human CD117 (dilution, 1/400; 30 min; 37°C) and biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (dilution, 1/700; 30 min; 37°C) antibodies. Immunostaining was revealed by a DABMap kit (Ventana, Illkirch, France). Finally, hematoxylin-erythrosin-saffron was applied to identify the nuclei and cytoplasm of cells. The number of mast cells was analyzed in at least 10 fields of stroma view per BF by using a Nikon 80i microscope coupled to a QICAM Qimaging camera fitted into a microscope. Mast cells were counted after image treatment with ImageJ 1.38X software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

IBDV neutralization test.

Virus neutralization (VN) tests were performed in CEF by using 100 median tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of IBDV strain CT (serotype 1) per well, as described previously (44). The VN titer was expressed as the log2 of the last serum dilution resulting in 100% neutralization of the cytopathogenic effect. VN titers higher than 3.3 were considered positive.

IBDV quantitation using qRT-PCR.

In experiments 2 and 3, a TaqMan-based quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) for IBDV segment A was implemented. A separate RT step allowed us to target the negative strand of the virus RNA, present in mature IBDV particles only. (This avoided subsequent quantitation of the positive-stranded transcript copies.) The virus load was expressed in EID50, calculated from the qRT-PCR values by using a standard curve prepared from serial 10-fold dilutions of an aliquoted and repeatedly egg-titrated reference suspension of mc94432.

In experiments 4 and 5, a tagged TaqMan-based qRT-PCR specific for the negative B strands of recombinant viruses was used. Briefly, the strand-specific qRT-PCR used a low concentration of a chimeric primer (including a virus-specific 3′ tail and an unrelated 5′ extension) at the reverse transcription step. cDNAs were then purified, and a set of specific primers and probe was used for quantitative PCR. The upper PCR primer and the probe were specific for the IBDV sequence, whereas the lower PCR primer had the same sequence as the 5′ extension of the chimeric RT primer (54).

Molecular identification of IBDV shed by inoculated birds.

The identities of IBDV strains in the BF of inoculated birds were confirmed either by partial sequencing of genome segments A and B in regions allowing the unambiguous identification of the recombinant viruses or by full-length sequencing of the segment A and B coding regions (mc94432-inoculated birds in experiment 5).

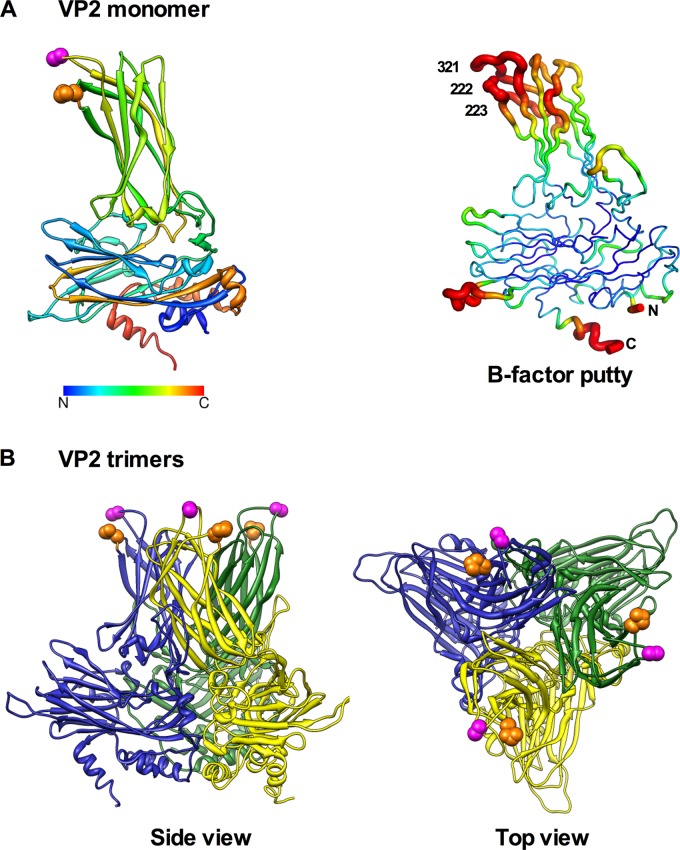

VP1 and VP2 structure images and VP1 aa 276 pocket prediction and crystal contact analysis.

Images of the structures of VP1 and VP2 were generated with the UCSF Chimera molecular modeling system, alpha version 1.3, and Protein Data Bank (PDB) files 2PGG and 1WCD, respectively. In Fig. 2A (right), the VP2 monomer is shown in a putty representation, generated by PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.3; Schrödinger, LLC), where color and width are proportional to the crystallographic temperature values. The crystal structure of VP1 was submitted to the CASTp server for prediction of pockets (55), and crystal contacts were analyzed with the CCP4 ACT program (56).

Fig 2.

Location of amino acid 321 in the VP2 crystal structure. (A) (Left) Amino acid 321 (magenta), located in the exposed hydrophilic peak B of the hypervariable domain, is shown in the crystal structure of the VP2 monomer (11) along with aa 222 and 223 (orange), which were identified as belonging to the Mab4 epitope (43, 44). Note that the variation in the number of spheres for a given amino acid is representative of the complexity of its side chain. (Right) The VP2 monomer is shown in a putty representation, where color and width are proportional to the crystallographic temperature values. The colors range from dark blue, corresponding to a B-factor minimum of 34, to red, corresponding to a B-factor maximum of 99. Amino acid 321 is indicated, along with aa 222 and 223. The amino and carboxy termini are labeled N and C, respectively. (B) Locations of aa 321, 222, and 223 in the VP2 trimers.

Molecular dynamics and analysis.

Birnavirus VP2 was used in its native form and with an A321V substitution for determination of the crystal structure (11) (PDB identification [ID] 1WCD) and was explicitly solvated with TIP3P water molecules and Na+ and Cl− counterions by using the VMD program (version 1.9.1) (57). Molecular dynamics simulations were performed under isobaric-isothermal conditions with periodic boundary conditions by using the NAMD program (version 2.7) (58) on the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (biowulf.nih.gov). Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle-Mesh Ewald summation. The CHARMM27 force field (59) was used with CHARMM atom types and charges. Prior to the start of the simulation, in silico minimization was performed using a conjugate gradient method, followed by slow warming to 310 K in 10 K increments. Each increment ran for 5 ps in order to equilibrate the system at a given temperature. Langevin dynamics were used to maintain the temperature, and a modified Nosé-Hoover Langevin piston was used to control the pressure. Once the 310 K target temperature was reached, each system was equilibrated for an additional 50 ps. Trial runs were conducted at 310 K for 5 ns, with data collected every ns. For all simulations, a 2-fs integration time step was used. Snapshots were output every 100 ps for further analysis. The counts of the pairwise hydrogen bonds and neighboring contacts from LigPlot (60) were averaged over these 200 snapshots, and standard deviations were calculated.

Statistical analysis.

Percentages were compared using the Fisher exact test. Small series of quantitative values were compared using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test for one-way analysis of variance. Bonferroni's correction for multiple comparisons was implemented where relevant. All statistical analyses were performed using Systat software, version 9.0 (Systat Software, Inc., 1998).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The full-length nucleotide sequences of segments A and B of virus 94432 have been submitted to the EMBL database (accession no. AM167550 and AM167551, respectively).

RESULTS

Both genome segments of 94432 are related to their counterparts in vvIBDVs but exhibit specific nucleotide or amino acid changes.

Both genome segments A and B were completely sequenced and were compared, by using a previously reported phylogenetic approach (41), with their counterparts in very virulent or attenuated IBDV strains retrieved from data banks. Genome segments A and B of 94432 exhibit significant phylogenetic relationships with their counterparts in vvIBDVs (100% bootstrap value), irrespective of the calculation method (data not shown).

Table 1 summarizes the genetic differences observed between 94432 and typical vvIBDV or attenuated IBDV strains. In segment A, the 5′ and 3′ NCRs of 94432 exhibited one and five nucleotide differences, respectively, from typical vvIBDV strain D6948. The coding region contained three amino acid differences between 94432 and the vvIBDV consensus, in VP5 (aa 78), VP2 (aa 321), and VP3 (aa 951). Based on the structure of VP2, amino acid position 321 is located in a flexible region exposed at the virus surface, between the H and I β-strands (11) (Fig. 2), and may be involved in antigenicity (9). Interestingly, the amino acid changes observed at positions 78 and 951 in 94432 had also been reported previously for vvIBDV strain UK661 (61). In 94432 segment B, the 5′ and 3′ NCRs exhibited no nucleotides different from those for D6948 (Table 1), whereas the VP1sequence exhibited five amino acid differences (V61I, S112P, T276A, A363V, and E763D) from the vvIBDV consensus.

Taken together, these results suggested that the attenuated phenotype of 94432 was not likely to be due to reassortment or recombination events with attenuated strains.

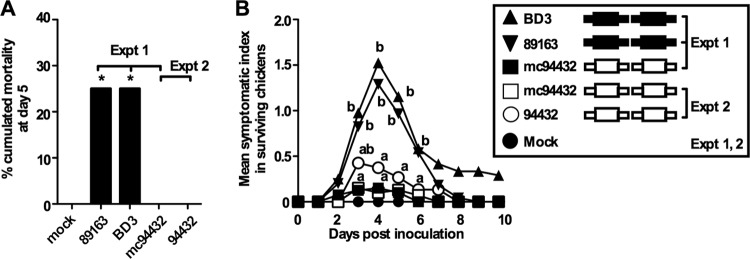

mc94432 and its parental strain, 94432, exhibit similar phenotypes.

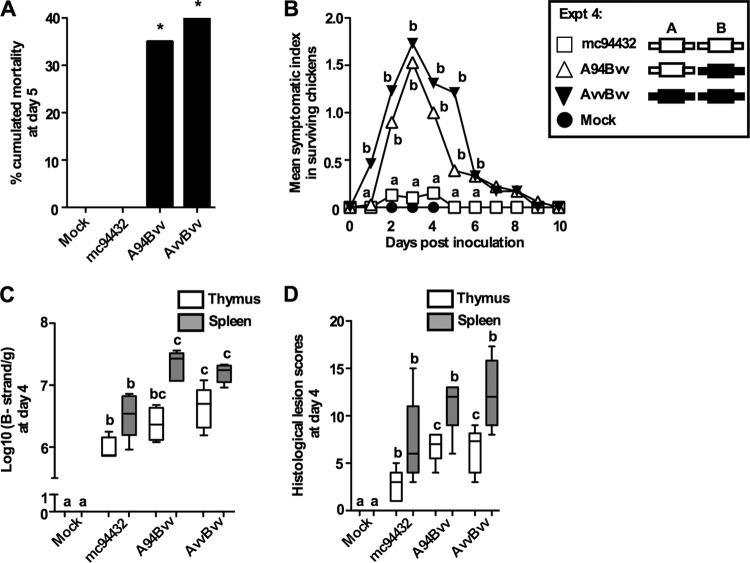

To determine the mutation(s) involved in the reduced pathogenicity of 94432, we developed a reverse genetics system for this virus and rescued its molecular clone mc94432. We first compared the phenotype of mc94432 with those of two typical vvIBDV strains, BD3 and 89163, and with that of its parental virus, 94432 (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

mc94432 is attenuated compared to typical vvIBDVs. The pathogenicity of mc94432 was first compared with those of typical vvIBDV strains BD3 and 89163 or with that of the parental strain, 94432. For the protocols of the animal experiments, see Table 2, experiments 1 and 2. (A) Percentages of cumulated mortality at 5 days postinfection. (B) Mean individual symptomatic index scores for surviving chickens from 1 to 10 days postinfection. Simplified representations of the recombinant segments A and B (based on those in Fig. 1) used to generate the indicated recombinant viruses are shown. Percentages of mortality were compared to that of the mock-infected group by using Fisher's exact test (*, P < 0.05). Multiple comparisons of symptomatic index scores were performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. Treatments sharing the same lowercase letter do not differ significantly at a confidence level (P) of ≤0.05.

Six-week-old SPF chickens were housed by groups of 20 to 25 under the same experimental conditions and were inoculated intranasally with a standard virus dose of 105 EID50. BD3 and 89163 each induced 25% mortality (Fig. 3A). This compared well with the 31% ± 8% mean mortality observed in seven repeated trials run under similar experimental conditions in our laboratory, with the 89163 virus used as a reference vvIBDV strain (data not shown). In sharp contrast, neither 94432 nor mc94432 induced any mortality (P ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, 94432 and mc94432 both induced mild signs in surviving chickens (maximum MSI scores for surviving chickens, 0.4 ± 0.7 and 0.2 ± 0.4, respectively, at day 3 postinoculation), whereas BD3 and 89163 both induced severe clinical signs (maximum MSI scores for surviving chickens, 1.5 ± 1.1 and 1.3 ± 1.2, respectively, at day 4 postinoculation) (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3B). These results confirmed that 94432 and mc94432 exhibited similar levels of pathogenicity, reduced from those of the typical vvIBDV strains.

The phenotypic similarity between 94432 and mc94432 was further confirmed by the fact that these two viruses induced very similar bursal atrophy, similar BLS at both 4 and 21 DPI, similar VN titers at 24 DPI, and similar virus titers at 4 DPI (data not shown). In addition, mc94432 exhibited the same atypical antigenic profile by AC-ELISA as the parental virus, 94432 (no binding of Mabs 3 and 4, minimal binding of Mab 5, and reduced binding of Mab 6 [Table 3]) (43).

Table 3.

Antigenic characterization of recombinant IBDV isolates by AC-ELISA

| IBDV strain | % AC-ELISA reactivitya of: |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mab 1 | Mab 3 | Mab 4 | Mab 5 | Mab 6 | Mab 7 | Mab 8 | Mab 9 | |

| F52/70 | 64b | 92 | 88 | 75 | 94 | 90 | 97 | 87 |

| 89163 | 47 | 2 | 10 | 48 | 90 | 89 | 55 | 66 |

| AvvB94 | 71 | 4 | 18 | 62 | 102 | 95 | 50 | 76 |

| A94[CRvv]B94 | 76 | 4 | 16 | 67 | 102 | 99 | 53 | 64 |

| r94A[V321A]B94 | 66 | 4 | 15 | 61 | 96 | 97 | 59 | 63 |

| 94432 | 70 | 3 | 0 | 12 | 20 | 97 | 78 | 42 |

| mc94432 | 61 | 2 | −1 | 7 | 16 | 87 | 67 | 43 |

| A94[NCR5′vv]B94 | 66 | 2 | −1 | 9 | 19 | 97 | 69 | 39 |

| A94[NCR3′vv]B94 | 79 | 3 | 1 | 13 | 23 | 98 | 73 | 49 |

Calculated as reported previously (43) by comparison with the binding efficiency of a reference polyclonal antibody (100% reactivity). A high percentage is correlated with efficient binding of the Mab to the captured virus. Reduced binding (between 15 and 25%) and lack of binding (<15%) of Mabs with the viruses tested are represented by boldface numbers or shading, respectively.

Mean percent reactivity in two repeated AC-ELISAs.

Taken together, these results convincingly support the assertion that mc94432 and the parental virus 94432 are attenuated and exhibit similar phenotypes.

Mutations in both segments A and B reduce 94432 pathogenicity.

To determine which genome segment of 94432 was responsible for the phenotype of this virus, we engineered several recombinant viruses (Fig. 1; Table 2).

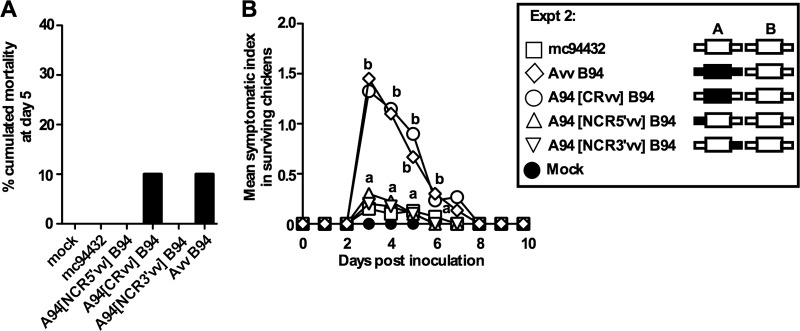

We first studied segment A mutations. Four viruses (Fig. 1A; Table 2, experiment 2) were rescued. Each contained the wild-type segment B of 94432, combined with a segment A into which mutations had been introduced, so that one or more of the 5′ NCR, the coding region, and the 3′ NCR would match the typical vvIBDV sequence. The in vivo pathogenicity of these newly generated viruses was compared to that of mc94432 by using the standardized experimental protocol described above. Only viruses containing a segment A with a vvIBDV-like coding region (A94[CRvv]B94 and AvvB94) induced mortality (10% in the two challenged groups [Fig. 4A]). A clear difference in severity was also apparent at the peak of clinical expression (3 DPI), when the MSI scores reached 1.5 ± 0.8 and 1.3 ± 0.8 for the groups challenged with AvvB94 and A94[CRvv]B94, respectively, but only 0.2 ± 0.4 to 0.3 ± 0.6 for the groups challenged with the other viruses (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Apart from the ability to induce mortality and severe clinical signs, the different recombinant viruses behaved extremely similarly in vivo, regardless of the parameters investigated (the virus titers in BF at 4 DPI, the BLS at 4 and 21 DPI, bursal atrophy, and the VN titers were not significantly different [data not shown]). Only A94[NCR5′vv]B94 replicated in the BF to a titer somewhat (0.5 log10) less but significantly lower than those of the other viruses (data not shown). These results showed that mutations in the coding region of segment A affect the pathogenicity of 94432.

Fig 4.

Segment A of 94432 is partially responsible for the reduced pathogenicity of this virus. The contribution of segment A to the reduced pathogenicity of 94432 was evaluated. For the protocol and genetic makeup of the viruses used in this animal experiment, see Table 2, experiment 2, and Fig. 1A. (A) Percentage of cumulated mortality at 5 days postinfection. (B) Mean individual symptomatic index scores from 1 to 10 days postinfection. Statistical analysis was performed as described for Fig. 3, and statistical differences are represented as in Fig. 3.

Interestingly, AvvB94 and A94[CRvv]B94 both induced less mortality (Fig. 4A) than expected for a typical vvIBDV (Fig. 3A) (2). This suggested that segment A was only partly involved and that mutations in segment B also contributed to the reduced pathogenicity of 94432. We investigated this issue by generating two viruses containing a vvIBDV-like segment B, in association with segment A of 94432 (A94Bvv) or with a vvIBDV-like segment A (AvvBvv) (Fig. 1B; Table 2, experiment 4). The pathogenicity of these two viruses was compared with that of mc94432 (Fig. 5A to D). Mortality was observed with A94Bvv and AvvBvv (33 and 40%, respectively), while no mortality was observed in the mc94432- and mock-inoculated control groups (P ≤ 0.05). In addition, A94Bvv and AvvBvv induced IBD signs with similar intensities (peak at 3 DPI; MSI scores, 1.5 ± 1.3 and 1.7 ± 1.1, respectively [Fig. 5B]), which also compared well with what had been observed previously for typical vvIBDV (Fig. 3B). In contrast, and as expected, mc94432 induced IBD signs of significantly lower intensity (maximum MSI score at 4 DPI, 0.2 ± 0.2) (P ≤ 0.05), which did not differ significantly from those observed in the mock-inoculated control group (Fig. 5B).

Fig 5.

Segment B of 94432 is mainly responsible for the reduced pathogenicity of this virus. The contribution of segment B to the reduced pathogenicity of mc94432 was evaluated. For the protocol and genetic makeup of the viruses used in this animal experiment, see Table 2, experiment 4, and Fig. 1B. (A) Percentage of cumulated mortality at 5 days postinfection, compared to that of the mock-infected group by using Fisher's exact test (*, P < 0.05). (B) Mean individual symptomatic index scores from 1 to 10 days postinfection. (C) Quantification of negative B strands in the thymus and spleen at 4 days postinfection (n, 4 to 5 chickens per group). (D) Histological lesion scores in the thymus and spleen at 4 days postinfection (n, 5 chickens per group). The box plots show the median flanked by the upper and lower quartiles. The outer bars show the range of values. Statistical analysis was performed as described for Fig. 3, and statistical differences are represented as in Fig. 3.

Remarkably, the increased pathogenicity of A94Bvv and AvvBvv, compared with that of mc94432 in experiment 4, was associated with the production by the former viruses of amounts of B strands in the thymus (AvvBvv) or spleen (A94Bvv and AvvBvv) slightly—but sometimes significantly—larger (P ≤ 0.05) than those for mc94432 (Fig. 5C). This increased pathogenicity was also associated with the induction by recombinant viruses A94Bvv and AvvBvv of significantly more histological damage in the thymus than that with mc94432 (mean TLS at 4 DPI, 6.8, 6.3, and 2.6, respectively; P ≤ 0.05 [Fig. 5D]). The same trend was also observed in the spleen, with mc94432 inducing mean SLS lower than those of A94Bvv and AvvBvv; however, the variability of SLS was higher, and the differences did not reach significance (Fig. 5D).

Taken together, these results showed that mutations in both segments A and B of 94432 contribute to the reduced pathogenicity of this virus. However, mutations in segment B have a greater impact.

The valine residue at VP2 position 321 contributes to reducing the pathogenicity of 94432.

We next wanted to determine which mutation(s) in the coding region of segment A of 94432 could affect pathogenicity. Because mutations L78 and V951 are also found in UK661, a typical vvIBDV strain (Table 1), it seemed unlikely that these mutations would contribute to reducing the pathogenicity of 94432. We therefore investigated the third mutation, introducing a valine at VP2 position 321. We rescued one recombinant virus containing segments A and B of 94432, but we replaced the V in position 321 of VP2 with an A, as found in a typical vvIBDV (A94[V321A]B94 [Fig. 1A; Table 2, experiment 3]). As anticipated from previous antigenic studies, A94[V321A]B94, AvvB94, and A94[CRvv]B94 all exhibited antigenic profiles typical of vvIBDVs, with no binding of Mab 3, minimal binding of Mab 4, and strong binding of Mabs 5 and 6 (Table 3), thus confirming experimentally that VP2 position 321 is critical to IBDV antigenicity.

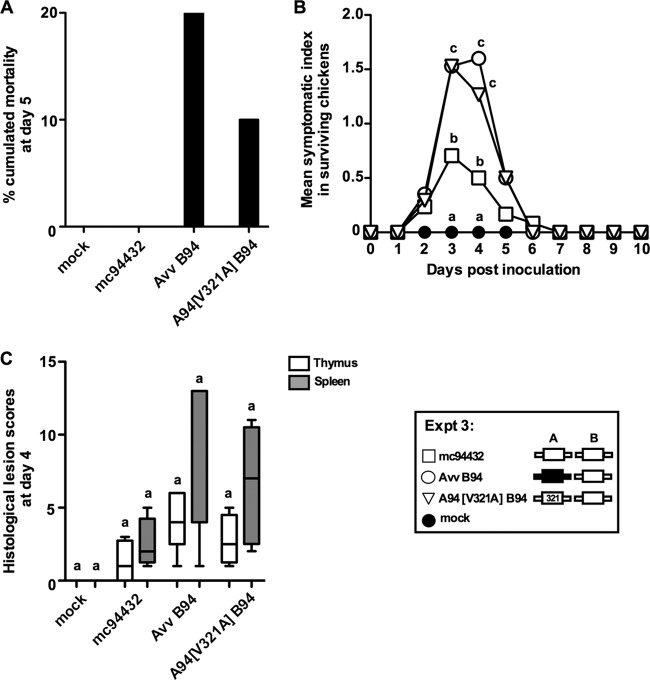

We next compared the pathogenicity of A94[V321A]B94 with those of AvvB94 and mc94432 (Fig. 6). AvvB94 and A94[V321A]B94 induced 20 and 10% mortality, respectively (although there was no statistically significant difference from controls), and typical severe IBD signs following the same time course (P, ≤0.05 for comparison with mc94432 and mock infection at 3 and 4 DPI). Interestingly, histological lesion scores in the spleen and thymus tended again to increase with the severity of the signs; however, this observation did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 6C). The responses to the different recombinant viruses were otherwise all similar, as measured by the BLS at 4 DPI; virus production in the BF, spleen, and thymus at 4 DPI; bursal atrophy; and the VN titer (data not shown). No significant differences were noticed at 1 DPI (data not shown).

Fig 6.

The valine residue at VP2 position 321 of segment A contributes to reducing the pathogenicity of 94432. The pathogenicities of mc94432, AvvB94, and A94[V321A]B94 were evaluated in SPF chickens. For the protocol and genetic makeup of the viruses used in this animal experiment, see Table 2, experiment 3, and Fig. 1A. (A) Percentage of cumulated mortality at 5 days postinfection. (B) Mean individual symptomatic index scores for surviving chickens from 1 to 10 days postinfection. See Materials and Methods for the method of calculation. (C) Histological lesion scores in the thymus and spleen at 4 days postinfection (n, 4 to 5 chickens per group). Statistical analysis was performed as for Fig. 3 and 5. Data are presented, and statistical differences are represented, as in Fig. 3 and 5.

Taken together these results showed that a valine residue at VP2 position 321 affects both the antigenicity and the pathogenicity of 94432.

The threonine residue at VP1 position 276 of segment B also contributes to the reduced pathogenicity of 94432.

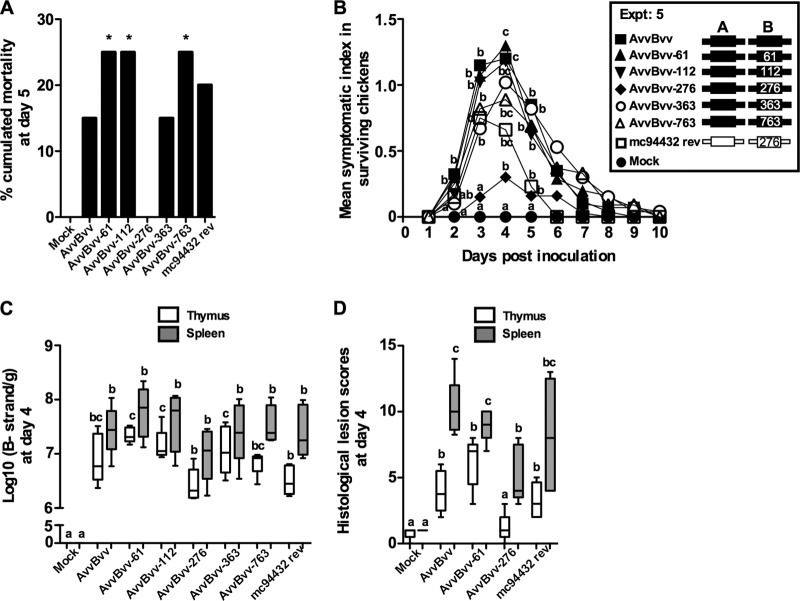

We next determined which mutation(s) in segment B of 94432 could contribute to modified pathogenicity. Five new recombinant viruses were rescued (Fig. 1B; Table 2, experiment 5). They all contained vvIBDV-like sequences in both segments A and B, but each retained 1 aa typical of 94432 in segment B (at position 61, 112, 276, 363, or 763).

All genetically modified viruses except AvvBvv-276 induced some mortality (Fig. 7A): AvvBvv-61, AvvBvv-112, and AvvBvv-763 induced 25% mortality (P, ≤0.05 for comparison with the AvvBvv-276- and mock-inoculated control groups). Clinical signs (Fig. 7B) peaked at 4 DPI. AvvBvv-276 proved significantly less pathogenic (MSI score, 0.3 ± 0.4) than AvvBvv and AvvBvv-61 (P ≤ 0.05), which did not differ significantly from AvvBvv-112, AvvBvv-363, and AvvBvv-763, with MSI scores ranging from 0.9 ± 1.0 to 1.3 ± 1.2 at 4 DPI.

Fig 7.

The threonine residue at VP1 position 276 of segment B mainly contributes to the reduced pathogenicity of 94432. The pathogenicities of mc94432, AvvBvv, AvvBvv-61, AvvBvv-112, AvvBvv-276, AvvBvv-363, and AvvBvv-763 were assessed in SPF chickens. For the protocol and genetic makeup of the viruses used in this animal experiment, see Table 2, experiment 5, and Fig. 1B. (A) Percentage of cumulated mortality at 5 days postinfection. (B) Mean individual symptomatic index scores for surviving chickens from 1 to 10 days postinfection. (C) Quantification of negative B strands in the thymus and spleen at 4 days postinfection (n, 4 to 5 chickens per group). (D) Histological lesion scores in the thymus and spleen at 4 days postinfection (n, 5 chickens per group). Statistical analysis was performed as for Fig. 3 and 5. Data are presented, and statistical differences are represented, as in Fig. 3 and 5.

Regarding the virus load at 4 DPI, no significant difference could be observed in the BF or in the spleen. However, in the thymus, AvvBvv-276 yielded significantly fewer B strands (6.43 log10) than did AvvBvv-61, AvvBvv-112, or AvvBvv-363 (7.07 to 7.35 log10) (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 7C). Consistently, there were significantly fewer thymic lesions at 4 DPI in the mock- and AvvBvv-276-inoculated groups (mean TLS, 0.8 and 1.2, respectively) than in the groups receiving AvvBvv or AvvBvv-61 (mean TLS, 4.0 and 6.2, respectively) (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 7D). The intensities of splenic lesions were also significantly lower with AvvBvv-276 (mean SLS, 5.2) than with AvvBvv or AvvBvv-61 (mean SLS, 10.3 or 9.0, respectively) (P ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 7D).

In agreement with the absence of significant differences in the bursal virus load at 4 DPI, there was also no significant difference in BLSs or mast cell counts at 4 DPI, or in b/B ratios at 21 DPI (data not shown).

A spontaneously occurring reversion in mc94432 confirms the attenuating role of VP1 position 276.

In contrast to the observations with mc94432 in our earlier experiments (0% mortality), the mc94432 challenge in experiment 5 induced 20% mortality (Fig. 7A), and the chickens inoculated with this virus exhibited typical IBD signs that peaked at 3 DPI (MSI score, 0.8 ± 1.1 [Fig. 7B]). This mortality rate did not differ significantly from that of the group that had received AvvBvv (15% mortality; MSI score at 3 DPI, 1.2 ± 0.9). By some criteria measured in experiment 5 after inoculation with mc94432, this virus resembled the less-pathogenic viruses (e.g., mc94432 replicated significantly less in the thymus at 4 DPI than AvvBvv-61 or AvvBvv-112 [P ≤ 0.05] [Fig. 7C]), but by others it resembled a more-pathogenic virus (e.g., mc94432 induced significantly more histological changes in the thymus than AvvBvv-276 [P ≤ 0.05] [Fig. 7D]).

To clarify the unusual pathogenicity of mc94432 in experiment 5, IBDV was isolated from the BF of all chickens that succumbed to mc94432 inoculation. The full-length coding regions of both segments A and B were sequenced and compared with the previously determined sequences of mc94432. This procedure revealed a single T276→A amino acid change at VP1 position 276 in segment B, which restored a vvIBDV-like amino acid. The same amino acid change was detected in the BF of all the other dead chickens of the same group. This emerging virus was a true revertant, since the corresponding plasmid (segment B of mc94432 with a single vvIBDV-like position, position 276) had never been generated. This situation was clearly different from that of all other inoculated groups in the same experiment, where the shed viruses indeed had the same sequence as the inoculated viruses (i.e., no spontaneous mutation had occurred).

DISCUSSION

IBDV isolate 94432 was known from partial sequences to be phylogenetically related to vvIBDVs (41, 62). This study confirms by full-genome analysis that it indeed is. The study further confirms our unpublished previous results showing that 94432 is surprisingly attenuated for a vvIBDV-related strain (no mortality and limited morbidity [Fig. 3A and B]). In the present study, we additionally investigated the relative contributions of both genome segments, A and B, to the unusual 94432 phenotype.

We found that VP2 amino acid mutation V321A was partly responsible for the low pathogenicity of 94432. However, the precise mechanism by which the V321A amino acid change might increase pathogenicity remains to be established. A321 is also present in classical virulent IBDV strains, such as F52/70 or CU-1wt, or in cell culture-adapted attenuated viruses (Table 1), all of which are less pathogenic than vvIBDV and induce minimal lesions in extrabursal organs. Hence, A321 in itself does not determine the pathogenic phenotype but is likely involved in interactions that allow other amino acids to contribute to pathogenicity. Alternatively, V321 may disrupt some interactions that are critical for the pathogenic phenotype or may create new ones that impair pathogenicity. The 3-dimensional structure of VP2 predicts that position 321 is located in one of the most flexible loops of the crystal structure (Fig. 2), connecting two of the β-strands (H and I) that build up the projection domain P, exposed at the virus surface (11). In short molecular dynamics simulations using the crystal structure of VP2 (11) in the native (A321) and variant (V321) forms, we observed significant differences in the conformation of the PHI loop relative to the PBC loop (data not shown). V321 is found to fold into the PBC loop. The PHI loop, centered on G319, opens away from the remainder of the PBC loop, allowing residues Y220, S315, and V256 to change their interactions.

How these modified interactions may influence pathogenicity is unclear. The possibility that position 321 is involved in interactions with an IBDV receptor cannot be ruled out. The sequence Ile-Asp-Ala (IDA) (aa 234 to 236) within the VP2 P domain was identified as a sequence matching the XDY triplet used by α4β1 integrin to bind fibronectin (63). Since the mutation at position 321 affects the structural area around aa 222 and 223, this amino acid could also influence interactions with fibronectin, due to the proximity to the IDA triplet. However, since most of the recombinant viruses studied here replicated to similar extents in the BF irrespective of their VP2 sequences, the hypothesis that differences in pathogenicity such as those observed here stem from different interactions with the IBDV receptor seems somewhat remote. Interestingly, vvIBDV strain 99323, which exhibits the A321T change, proved as pathogenic as French vvIBDV reference isolate 89163 under the same experimental conditions as those used here (52). Comparison of the molecular structures of the V and T residues suggests a critical role for the methyl group found at the γ position in the V321 residue, which would result in low pathogenicity, whereas a hydroxyl group, such as that found at the γ position in the T321 residue, would not.

The antigenic consequences of the VP2 structural changes predicted are more readily clarified. Indeed, the present results confirm experimentally that VP2 position 321 modulates the binding to the epitopes probed by Mabs 4, 5, and 6 (Table 3). The binding of Mab 4 had been shown previously to be affected by changes occurring in amino acid positions 222 and 223 of the PBC loop (43, 44). Hence, the antigenic changes observed here are consistent with the structural predictions that changes at position 321 (PHI loop) will induce some changes in interactions with the PBC loop. The amino acids predicted to exhibit modified interactions are Y220, belonging to major hydrophilic peak A, and V256, located close to minor hydrophilic peak B, both located in VP2 regions suspected to have strong antigenic significance (10). Remarkably, position 321 is mutated from A to E in the U.S. variant IBDV GLS-5, which is also extensively antigenically modified (43). In addition, in 99323, a vvIBDV strain that is also extensively antigenically modified (52), position 220 is changed from Y to F and position 321 from A to T (52), an observation that further substantiates the possible interactions between residues 220 and 321.

Taken together, our results with segment A suggest that conformational changes affecting position 321 may have important effects in trans, by altering local conformation, which may in turn affect the interactions of VP2 involving these loops, with consequences for both pathogenicity and antigenicity. This would have to be confirmed by a complementary and reciprocal study introducing the single A321V change into another vvIBDV genetic background.

Although VP2 position 321 contributes to the attenuated phenotype of strain 94432, our findings demonstrate that segment B and the viral polymerase are primarily responsible for this reduced pathogenicity. Indeed, AvvBvv and A94Bvv were as pathogenic as wild-type vvIBDVs under similar experimental conditions (Fig. 5A and B). The literature regarding the role of a vvIBDV-like VP1 in pathogenicity is somewhat conflicting. In one study, a recombinant virus with segment A derived from the cell culture-adapted strain CEF94 and segment B derived from the vvIBDV strain D6948 failed to induce mortality (31). However, in another study, two natural reassortant strains with similar genetic makeups induced 20 to 30% mortality (64, 65). The current study demonstrates that both genomic segments of 94432, both of which are phylogenetically related to those of vvIBDVs, do contribute to pathogenicity. This primary contribution of VP1 to the pathogenicity of vvIBDV is consistent with the findings of a chronophylogenetic study suggesting that vvIBDV expansion was almost concomitant with the emergence of the typical vvIBDV-like segment B (38).

The present study further suggests a critical role for VP1 residue 276 in both the pathogenicity of vvIBDV strains (which have an alanine at position 276) and the attenuated phenotype of 94432 (which has a threonine at position 276). Indeed, no mortality and significantly reduced morbidity were observed with AvvBvv-276, which was also more closely related to 94432 than any other virus with regard to the other pathogenicity criteria (Fig. 7). The implication of position 276 in the reduced pathogenicity of 94432 was also fortuitously confirmed in experiment 5, when a pathogenic revertant derived from mc94432 emerged spontaneously. Full-length sequencing of this revertant demonstrated that the only amino acid change associated with its increased pathogenicity was T276→A, the reciprocal change of the attenuating mutation studied in AvvBvv-276. However, in spite of these convincing results, alanine 276 cannot be considered an absolute marker of pathogenicity, since it is also present in attenuated cell culture-adapted IBDV strains P2, CEF94, and CT.

VP1 position 276 is located in the α6 helix of the “finger” subdomain of VP1 (45). To our knowledge, position 276 has not been identified in previous studies as having a significant structural or functional role. Position 276 lies at the nadir of a partially exposed, predominantly hydrophobic groove on the surface of VP1. This observation was confirmed quantitatively by analysis with CASTp, which ranked a predicted pocket including and surrounding position 276 fourth among 96 predicted pockets (data not shown). This pocket was found to be partially occupied by a loop spanning residues 292 to 297 of a symmetry-related VP1 monomer in the crystal structure. What structural consequences the changes at position 276 may have, and how these changes may influence pathogenicity (for instance, by disrupting some interactions that are normally required for expression of the vvIBDV phenotype), is not known yet. Only one segment B sequence of an attenuated vvIBDV (IBDVmd) is available from data banks. It reveals two genetic changes, at VP1 positions 96 and 161, from its vvIBDV parent strain (IBDVks) (66). An alanine at position 276 is also present in these particular strains and thus is not a prerequisite for vvIBDV attenuation. However, positions 96 and 276 are brought into close proximity by protein folding (25, 45). Hence, the same VP1 domain might have been affected by different mutations in IBDVks and in the pathogenic vvIBDV parent of 94432. Further insights might come from comparative studies between related polymerases: infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV) has valine (V265), which is isosteric with threonine, at the homologous position (67). Three positions surrounding Val265 in the IPNV crystal structures exhibit hydrophobic amino acids smaller than those in IBDV VP1. It is possible that these smaller amino acids maintain the backbone conformation in this region by accommodating the additional methyl groups of a valine (compared to an alanine) at position 276. Taken together, these observations suggest the possibility that the introduction of a hydroxyl group by the alanine-to-threonine alteration at position 276 may change intermolecular interactions between this VP1 hydrophobic pocket and another, as yet unidentified molecule. The potential effect of the T276A substitution on intra- and intermolecular interactions will need to be evaluated in additional studies.

Finally, the present study also highlights an interesting aspect of the pathogenesis of acute IBD. It is indeed striking that apart from mortality and the severity of clinical signs, the only parameter to be significantly modified for most of the pathogenic viruses (Avv B94, A94[CRvv]B94, A94[V321A]B94, A94Bvv, AvvBvv, and AvvBvv-61) was the ability to induce histological lesions in extrabursal lymphoid organs, such as the spleen and the thymus (Fig. 5C and D, 6C, and 7C and D). This observation is consistent with previous reports showing that vvIBDVs cause extensive histological damage in nonbursal lymphoid organs (68–71). It has been suggested that an immunopathological mechanism may play a role in vivo in the development of IBD-induced lesions (71). Whether such a mechanism could explain more-severe lesions in extrabursal organs is not known.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that both genome segments are important for vvIBDV pathogenicity and provide new targets for their attenuation using reverse genetics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rudiger Raue for help with the development of IBDV reverse genetics in our laboratory and Gaelle Rivallan, Marylin Queguiner, and Yannick Morin for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by research grant 2002-7 from the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety (Anses), by COST Action 839 “Immunosuppressive Viral Diseases of Chickens,” and by the Conseil General des Cotes d'Armor.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 December 2012

REFERENCES

- 1. Lasher HN, Shane SM. 1994. Infectious bursal disease. World's Poult. Sci. J. 50:133–166 [Google Scholar]

- 2. van den Berg TP. 2000. Acute infectious bursal disease in poultry: a review. Avian Pathol. 29:175–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rauw F, Lambrecht B, van den Berg T. 2007. Pivotal role of ChIFNγ in the pathogenesis and immunosuppression of infectious bursal disease. Avian Pathol. 36:367–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang D, Liu Y, She R, Xu J, Liu L, Xiong J, Yang Y, Sun Q, Peng K. 2009. Reduced mucosal injury of SPF chickens by mast cell stabilization after infection with very virulent infectious bursal disease virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 131:229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hassan MK, Al-Natour MQ, Ward LA, Saif YM. 1996. Pathogenicity, attenuation, and immunogenicity of infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Dis. 40:567–571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muller H, Mundt E, Eterradossi N, Islam MR. 2012. Current status of vaccines against infectious bursal disease. Avian Pathol. 41:133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Delmas B, Kibenge FSB, Leong JC, Mundt E, Vakharia VN, Wu JL. 2004. Birnaviridae, p 561–569 In Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. (ed), Virus taxonomy. Eighth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 8. Muller H, Becht H. 1982. Biosynthesis of virus-specific proteins in cells infected with infectious bursal disease virus and their significance as structural elements for infectious virus and incomplete particles. J. Virol. 44:384–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Letzel T, Coulibaly F, Rey FA, Delmas B, Jagt E, van Loon AA, Mundt E. 2007. Molecular and structural bases for the antigenicity of VP2 of infectious bursal disease virus. J. Virol. 81:12827–12835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schnitzler D, Bernstein F, Muller H, Becht H. 1993. The genetic basis for the antigenicity of the VP2 protein of the infectious bursal disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Part 8):1563–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coulibaly F, Chevalier C, Gutsche I, Pous J, Navaza J, Bressanelli S, Delmas B, Rey FA. 2005. The birnavirus crystal structure reveals structural relationships among icosahedral viruses. Cell 120:761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Birghan C, Mundt E, Gorbalenya AE. 2000. A non-canonical Lon proteinase lacking the ATPase domain employs the Ser-Lys catalytic dyad to exercise broad control over the life cycle of a double-stranded RNA virus. EMBO J. 19:114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lejal N, Da Costa B, Huet JC, Delmas B. 2000. Role of Ser-652 and Lys-692 in the protease activity of infectious bursal disease virus VP4 and identification of its substrate cleavage sites. J. Gen. Virol. 81:983–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casanas A, Navarro A, Ferrer-Orta C, Gonzalez D, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2008. Structural insights into the multifunctional protein VP3 of birnaviruses. Structure 16:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kibenge FS, Dhillon AS, Russell RG. 1988. Biochemistry and immunology of infectious bursal disease virus. J. Gen. Virol. 69(Part 8):1757–1775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kochan G, Gonzalez D, Rodriguez JF. 2003. Characterization of the RNA-binding activity of VP3, a major structural protein of infectious bursal disease virus. Arch. Virol. 148:723–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luque D, Rivas G, Alfonso C, Carrascosa JL, Rodriguez JF, Caston JR. 2009. Infectious bursal disease virus is an icosahedral polyploid dsRNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:2148–2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tacken MG, Peeters BP, Thomas AA, Rottier PJ, Boot HJ. 2002. Infectious bursal disease virus capsid protein VP3 interacts both with VP1, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, and with viral double-stranded RNA. J. Virol. 76:11301–11311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mundt E, Beyer J, Muller H. 1995. Identification of a novel viral protein in infectious bursal disease virus-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 76(Part 2):437–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lombardo E, Maraver A, Espinosa I, Fernandez-Arias A, Rodriguez JF. 2000. VP5, the nonstructural polypeptide of infectious bursal disease virus, accumulates within the host plasma membrane and induces cell lysis. Virology 277:345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu M, Vakharia VN. 2006. Nonstructural protein of infectious bursal disease virus inhibits apoptosis at the early stage of virus infection. J. Virol. 80:3369–3377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yao K, Vakharia VN. 2001. Induction of apoptosis in vitro by the 17-kDa nonstructural protein of infectious bursal disease virus: possible role in viral pathogenesis. Virology 285:50–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Macreadie IG, Azad AA. 1993. Expression and RNA dependent RNA polymerase activity of birnavirus VP1 protein in bacteria and yeast. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 30:1169–1178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. von Einem UI, Gorbalenya AE, Schirrmeier H, Behrens SE, Letzel T, Mundt E. 2004. VP1 of infectious bursal disease virus is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. J. Gen. Virol. 85:2221–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garriga D, Navarro A, Querol-Audi J, Abaitua F, Rodriguez JF, Verdaguer N. 2007. Activation mechanism of a noncanonical RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:20540–20545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muller H, Nitschke R. 1987. The two segments of the infectious bursal disease virus genome are circularized by a 90,000-Da protein. Virology 159:174–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Irigoyen N, Garriga D, Navarro A, Verdaguer N, Rodriguez JF, Caston JR. 2009. Autoproteolytic activity derived from the infectious bursal disease virus capsid protein. J. Biol. Chem. 284:8064–8072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chevalier C, Lepault J, Da Costa B, Delmas B. 2004. The last C-terminal residue of VP3, glutamic acid 257, controls capsid assembly of infectious bursal disease virus. J. Virol. 78:3296–3303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mundt E, Vakharia VN. 1996. Synthetic transcripts of double-stranded Birnavirus genome are infectious. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:11131–11136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zierenberg K, Raue R, Nieper H, Islam MR, Eterradossi N, Toquin D, Muller H. 2004. Generation of serotype 1/serotype 2 reassortant viruses of the infectious bursal disease virus and their investigation in vitro and in vivo. Virus Res. 105:23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boot HJ, ter Huurne AA, Hoekman AJ, Peeters BP, Gielkens AL. 2000. Rescue of very virulent and mosaic infectious bursal disease virus from cloned cDNA: VP2 is not the sole determinant of the very virulent phenotype. J. Virol. 74:6701–6711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lim BL, Cao Y, Yu T, Mo CW. 1999. Adaptation of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus to chicken embryonic fibroblasts by site-directed mutagenesis of residues 279 and 284 of viral coat protein VP2. J. Virol. 73:2854–2862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mundt E. 1999. Tissue culture infectivity of different strains of infectious bursal disease virus is determined by distinct amino acids in VP2. J. Gen. Virol. 80(Part 8):2067–2076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qi X, Gao H, Gao Y, Qin L, Wang Y, Gao L, Wang X. 2009. Naturally occurring mutations at residues 253 and 284 in VP2 contribute to the cell tropism and virulence of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus. Antiviral Res. 84:225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Loon AA, de Haas N, Zeyda I, Mundt E. 2002. Alteration of amino acids in VP2 of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus results in tissue culture adaptation and attenuation in chickens. J. Gen. Virol. 83:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Raue R, Islam MR, Islam MN, Islam KM, Badhy SC, Das PM, Muller H. 2004. Reversion of molecularly engineered, partially attenuated, very virulent infectious bursal disease virus during infection of commercial chickens. Avian Pathol. 33:181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boot HJ, Hoekman AJ, Gielkens AL. 2005. The enhanced virulence of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus is partly determined by its B-segment. Arch. Virol. 150:137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hon CC, Lam TY, Drummond A, Rambaut A, Lee YF, Yip CW, Zeng F, Lam PY, Ng PT, Leung FC. 2006. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a correlation between the expansion of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus and reassortment of its genome segment B. J. Virol. 80:8503–8509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Islam MR, Zierenberg K, Muller H. 2001. The genome segment B encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase protein VP1 of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) is phylogenetically distinct from that of all other IBDV strains. Arch. Virol. 146:2481–2492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jackwood DJ, Sommer-Wagner SE, Crossley BM, Stoute ST, Woolcock PR, Charlton BR. 2011. Identification and pathogenicity of a natural reassortant between a very virulent serotype 1 infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) and a serotype 2 IBDV. Virology 420:98–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Le Nouen C, Rivallan G, Toquin D, Darlu P, Morin Y, Beven V, de Boisseson C, Cazaban C, Comte S, Gardin Y, Eterradossi N. 2006. Very virulent infectious bursal disease virus: reduced pathogenicity in a rare natural segment-B-reassorted isolate. J. Gen. Virol. 87:209–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Le Nouën C, Toquin D, Muller H, Raue R, Kean KM, Langlois P, Cherbonnel M, Eterradossi N. 2012. Different domains of the RNA polymerase of infectious bursal disease virus contribute to virulence. PLoS One 7:e28064 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0028064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Eterradossi N, Arnauld C, Toquin D, Rivallan G. 1998. Critical amino acid changes in VP2 variable domain are associated with typical and atypical antigenicity in very virulent infectious bursal disease viruses. Arch. Virol. 143:1627–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Eterradossi N, Toquin D, Rivallan G, Guittet M. 1997. Modified activity of a VP2-located neutralizing epitope on various vaccine, pathogenic and hypervirulent strains of infectious bursal disease virus. Arch. Virol. 142:255–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pan J, Vakharia VN, Tao YJ. 2007. The structure of a birnavirus polymerase reveals a distinct active site topology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7385–7390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Eterradossi N, Rivallan G, Toquin D, Guittet M. 1997. Limited antigenic variation among recent infectious bursal disease virus isolates from France. Arch. Virol. 142:2079–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bygrave AC, Faragher JT. 1970. Mortality associated with Gumboro disease. Vet. Rec. 86:758–759 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Islam MR, Zierenberg K, Eterradossi N, Toquin D, Rivallan G, Muller H. 2001. Molecular and antigenic characterization of Bangladeshi isolates of infectious bursal disease virus demonstrate their similarities with recent European, Asian and African very virulent strains. J. Vet. Med. B Infect. Dis. Vet. Public Health 48:211–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Eterradossi N, Picault JP, Drouin P, Guittet M, L'Hospitalier R, Bennejean G. 1992. Pathogenicity and preliminary antigenic characterization of six infectious bursal disease virus strains isolated in France from acute outbreaks. Zentralbl. Veterinarmed. B 39:683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Reed LJ, Muench H. 1938. A simple method of estimation of fifty per cent end-points. Am. J. Hyg. 27:493–497 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mundt E, Muller H. 1995. Complete nucleotide sequences of 5′- and 3′-noncoding regions of both genome segments of different strains of infectious bursal disease virus. Virology 209:10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eterradossi N, Gauthier C, Reda I, Comte S, Rivallan G, Toquin D, de Boisseson C, Lamande J, Jestin V, Morin Y, Cazaban C, Borne PM. 2004. Extensive antigenic changes in an atypical isolate of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus and experimental clinical control of this virus with an antigenically classical live vaccine. Avian Pathol. 33:423–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Skeeles JK, Luckert PD, Fletcher OJ, Leonard DJ. 1979. Immunization studies with a cell culture adapted infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Dis. 23:456–465 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Escaffre O, Queguiner M, Eterradossi N. 2010. Development and validation of four real-time quantitative RT-PCRs specific for the positive or negative strands of a bisegmented dsRNA viral genome. J. Virol. Methods 170:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, Liang J. 2006. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W116–W118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 67:235–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. 1996. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14:33–38, 27–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. 2005. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26:1781–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Brooks BR, Brooks CL, III, Mackerell AD, Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartels C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Kuczera K, Lazaridis T, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. 2009. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 30:1545–1614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. 1995. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 8:127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Brown MD, Skinner MA. 1996. Coding sequences of both genome segments of a European ‘very virulent’ infectious bursal disease virus. Virus Res. 40:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Eterradossi N, Arnauld C, Tekaia F, Toquin D, Le Coq H, Rivallan G, Guittet M, Domenech J, van den Berg TP, Skinner MA. 1999. Antigenic and genetic relationships between European very virulent infectious bursal disease viruses and an early West African isolate. Avian Pathol. 28:36–46 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Delgui L, Ona A, Gutierrez S, Luque D, Navarro A, Caston JR, Rodriguez JF. 2009. The capsid protein of infectious bursal disease virus contains a functional α4 β1 integrin ligand motif. Virology 386:360–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wei Y, Li J, Zheng J, Xu H, Li L, Yu L. 2006. Genetic reassortment of infectious bursal disease virus in nature. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 350:277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wei Y, Yu X, Zheng J, Chu W, Xu H, Yu L. 2008. Reassortant infectious bursal disease virus isolated in China. Virus Res. 131:279–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lazarus D, Pasmanik-Chor M, Gutter B, Gallili G, Barbakov M, Krispel S, Pitcovski J. 2008. Attenuation of very virulent infectious bursal disease virus and comparison of full sequences of virulent and attenuated strains. Avian Pathol. 37:151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Graham SC, Sarin LP, Bahar MW, Myers RA, Stuart DI, Bamford DH, Grimes JM. 2011. The N-terminus of the RNA polymerase from infectious pancreatic necrosis virus is the determinant of genome attachment. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002085 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rautenschlein S, Yeh HY, Sharma JM. 2003. Comparative immunopathogenesis of mild, intermediate, and virulent strains of classic infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Dis. 47:66–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tanimura N, Tsukamoto K, Nakamura K, Narita M, Maeda M. 1995. Association between pathogenicity of infectious bursal disease virus and viral antigen distribution detected by immunohistochemistry. Avian Dis. 39:9–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tsukamoto K, Tanimura N, Mase M, Imai K. 1995. Comparison of virus replication efficiency in lymphoid tissues among three infectious bursal disease virus strains. Avian Dis. 39:844–852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Williams AE, Davison TF. 2005. Enhanced immunopathology induced by very virulent infectious bursal disease virus. Avian Pathol. 34:4–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pan J, Lin L, Tao YJ. 2009. Self-guanylylation of birnavirus VP1 does not require an intact polymerase activity site. Virology 395:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]