Abstract

Our previous study had reported on the interaction of rotavirus NSP1 with cellular phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) during activation of the PI3K pathway (P. Bagchi et al., J. Virol. 84:6834–6845, 2010). In this study, we have analyzed the molecular mechanism behind this interaction. Results showed that this interaction is direct and that both α and β isomers of the PI3K regulatory subunit p85 and full-length NSP1 are important for this interaction, which results in efficient activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway during rotavirus infection.

TEXT

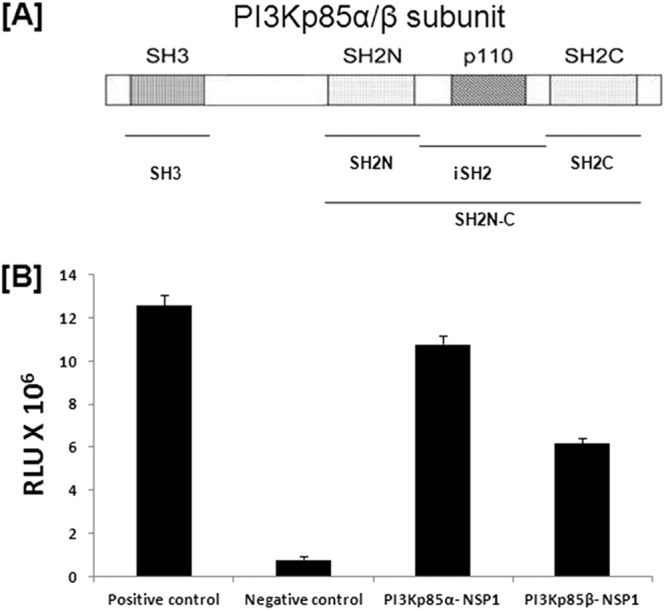

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) regulate an array of protein kinase signaling cascades that, in turn, control diverse cellular processes like cell survival, metabolism, proliferation, and inflammation/immunity. Class IA PI3Ks are dimeric enzymes consisting of a p110 catalytic subunit attached to a smaller, noncatalytic, regulatory subunit (typically p85). The p85 regulatory subunit contains an N-terminal SH3 (Src homology 3) domain, a BH (B-cell receptor homology) domain flanked by proline-rich sequences, and two SH2 (Src homology 2) domains (Fig. 1A). The two SH2 domains are on either side of the p110-binding inter-SH2 (iSH2) domain, which facilitates interaction between the p85 and p110 subunits. Both SH2 domains as well as the SH3 domain are responsible for the binding of the p85/p110 heterodimer with receptor tyrosine kinases. The p85/p110 heterodimer assembly does not itself result in marked enzyme activation. Generally, binding of the phosphotyrosine sites of activator proteins with SH2 or SH3 domains of p85 causes a conformational change in the heterodimer leading to enzyme activation (1).

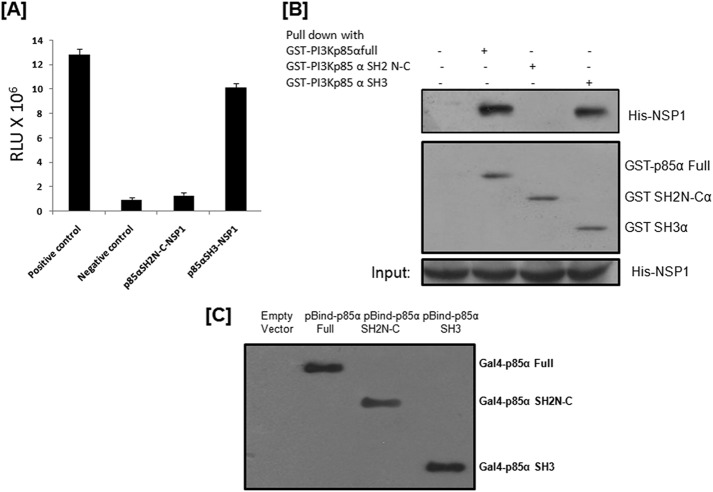

Fig 1.

Rotavirus NSP1 directly interacts with the regulatory subunit of PI3K (p85). (A) Graphical representation of the PI3K p85α/β subunit, which contains one SH3 domain, two SH2 domains, and a p110 subunit binding region between two SH2 domains. (B) The mammalian two-hybrid assay showed direct interaction of RV NSP1 with α and β isomers of the p85 subunit. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector constructs. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI). The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5). RLU, relative luciferase units.

The mechanism of interaction between viral and host cellular proteins is important for selecting probable drug targets. Activation or inactivation of the host protein by viral protein could be due to a direct interaction between two proteins or could be indirect in that the viral protein may interact with some other upstream host protein of the signaling cascade, which in turn modulates the target host protein. Various mechanisms by which viruses activate the PI3K/Akt pathway have been reported (2–7). For example, influenza virus NS1 protein directly interacts with PI3K and activates the PI3K/Akt pathway (8, 9) whereas high-risk human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) encodes a putative integral membrane protein, E5, which stimulates activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) through dimerization and autophosphorylation, and this subsequently results in the upregulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (10, 11).

Our previous study had shown that rotavirus (RV) nonstructural protein 1 (NSP1) interacts with PI3K (12) to activate the PI3K pathway. However, the exact molecular mechanism of the interaction was not defined. In this study, we have tried to analyze whether the PI3K-NSP1 interaction is direct or is a result of multiprotein assembly. The NSP1 gene sequence of rotavirus (RV) strain SA11 (accession number DQ838599.2) was used for cloning throughout the study. Generally, two isomers of PI3K regulatory subunits (p85α and p85β) are involved in direct interaction with viral proteins to activate the PI3K/Akt pathway. Some viruses like influenza virus are reported to interact with p85β, while a virus like bursal disease virus interacts with p85α to activate the PI3K pathway (8, 9, 13).

Rotavirus NSP1 directly interacts with the regulatory subunit of PI3K (p85).

A mammalian two-hybrid assay using the CheckMate mammalian two-hybrid system (Promega, WI) was done to study the direct interaction of rotavirus NSP1 with p85α or p85β. At first, NSP1 was cloned in the pACT vector whereas p85α and p85β were cloned in the pBIND vector. Either pBIND-p85α or pBIND-p85β was cotransfected with pACT-NSP1 and pG5luc to carry out the mammalian two-hybrid assay. Our data showed a 10- to 11-fold increase in luciferase units during interaction of NSP1 with the p85α subunit and a 5- to 6-fold increase in luciferase units during NSP1-p85β interaction, both compared to the negative control (Fig. 1B). This result suggested that rotavirus NSP1 can directly interact with both p85α and p85β, though interaction efficiency varies. Similar results were obtained with NSP1 of another wild-type RV strain, A5-13, suggesting that this interaction is rotavirus strain independent (data not shown).

The SH3 domain of p85α and the region from the N-terminal to the C-terminal SH2 domain of p85β are involved in direct interaction of PI3K with NSP1.

As both the α and β subunits of p85 were found to directly interact with NSP1 (Fig. 1B), we next tried to analyze the exact domain or region required for this interaction. Initially, the p85α-NSP1 interaction was assessed by cloning the SH3 domain and the region spanning the SH2N to SH2C domain (SH2N-C) (Fig. 1A) of p85α individually in the pBIND vector, followed by cotransfecting either of them with pACT-NSP1 and pG5luc to perform the mammalian two-hybrid assay. The assay showed a 10- to 11-fold increase in luciferase units during the p85α SH3 domain-NSP1 interaction compared to the negative control, while we found no direct interaction between the SH2N-C domain of p85α and NSP1 (Fig. 2A). For additional confirmation, the glutathione S-transferase (GST) pulldown assay was done according to the manufacturer's protocol (GST pulldown assay kit; Thermo Scientific, IL). At first, GST-tagged full-length p85α, p85α SH2N-C, or p85α SH3 was induced in bacterial cells (Escherichia coli C41), captured by glutathione beads, and incubated with in vitro-translated (in vitro transcription-translation kit; Promega, WI) His-tagged NSP1, followed by pulldown using the GST pulldown assay kit. Immunoblotting of precipitate confirmed that the SH3 domain in p85α directly interacts with RV NSP1 (Fig. 2B).

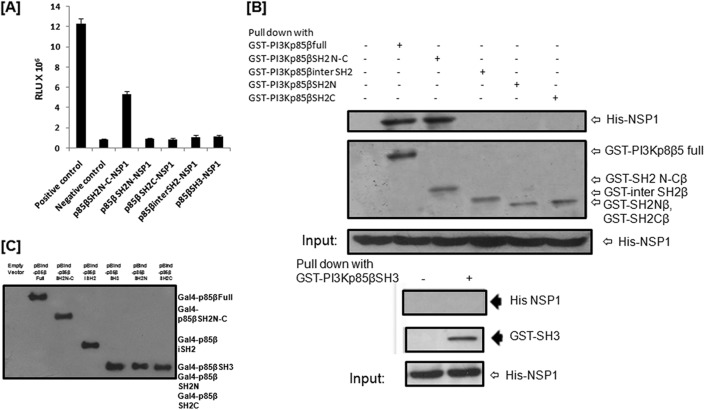

Fig 2.

The SH3 domain of p85α is involved in the direct interaction of PI3K with RV NSP1. (A) The mammalian two-hybrid assay showed direct interaction of RV NSP1 with the SH3 domain of the p85α subunit. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector constructs. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI). The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5). (B) GST-tagged full-length p85α, p85α SH3, and p85α SH2N-C were overexpressed, pulled down by glutathione beads, and then incubated with in vitro-translated His-tagged SA11 NSP1. Samples were Western blotted with monoclonal anti-His antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), which validated the SA11 NSP1-p85α SH3 interaction. The blot was also reprobed with anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) to verify the expression of GST-tagged proteins. (C) Western blot data showed expression levels of full-length p85α, p85α SH3, and p85α SH2N-C in a mammalian two-hybrid assay vector using GAL4 (DNA binding domain) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA).

In the case of p85β-NSP1 interaction, mammalian two-hybrid data revealed that the SH3 domain of p85β does not interact with NSP1, while a 5- to 5.5-fold increase in luciferase activity was observed in the p85β SH2N-C–NSP1 interaction compared to the negative control (Fig. 3A). To locate the domain within the SH2N-C region, SH2N, SH2C, and the intermediate region (iSH2) (Fig. 1A) were cloned individually in the pBIND vector. The mammalian two-hybrid assay revealed that NSP1 does not directly interact with SH2N, SH2C, or iSH2 regions of p85β individually (Fig. 3A). This result suggests that the total region from the N-terminal to the C-terminal SH2 domain of p85β is important for direct interaction with NSP1. Our mammalian two-hybrid assay data were further confirmed by GST pulldown assay (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

The region from the N-terminal to the C-terminal SH2 domain of p85β is involved in the direct interaction of PI3K with RV NSP1. (A) The mammalian two-hybrid assay showed direct interaction of RV NSP1 with the region from the N-terminal to the C-terminal SH2 domain of p85β. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector constructs. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI). The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5). (B) GST-tagged full-length p85β, p85β SH3, p85β SH2N-C, p85β SH2N, p85β SH2C, and p85β inter-SH2 were overexpressed, pulled down by glutathione beads, and then incubated with in vitro-translated His-tagged SA11 NSP1. Then, samples were Western blotted with monoclonal anti-His antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA), which validated the SA11 NSP1-p85β SH2N-C interaction. The blot was also reprobed with anti-GST antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) to verify the expression of GST-tagged proteins. (C) Western blot data showed expression levels of all p85β constructs in the mammalian two-hybrid vector using GAL4 (DNA binding domain) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA).

Both N- and C-terminal regions of NSP1 can directly and individually interact with p85α, but full-length NSP1 is important for efficient interaction with p85β.

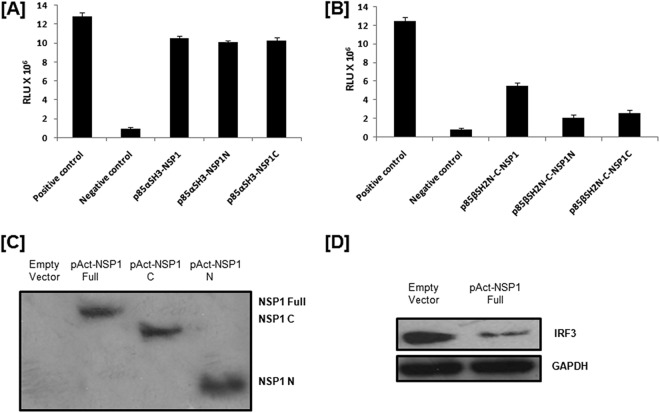

Since NSP1 binding regions within the p85 subunit of PI3K were identified, the next question was to identify the domain of NSP1 which is necessary for this interaction. Rotavirus NSP1 is not a conserved protein, and there are no known strain-independent universal SH2 or SH3 binding domains. Based on the deduced structure of NSP1, NSP1 was broadly divided into two regions, i.e., the more conserved N-terminal region (1 to 100 amino acids) (C-X2-C-X8-C-X2-C-X3-H-X-C-X2-C-X-5-C), a putative zinc finger motif comprising the cysteine-rich domain (NSP1N) (14), and the variable C-terminal region of NSP1 (NSP1C). We cloned NSP1N and NSP1C in the pACT vector to study p85α SH3-NSP1N and p85α SH3-NSP1C interactions by the mammalian two-hybrid assay, which revealed that NSP1 full length (NSP1FL), NSP1N, and NSP1C can directly and individually interact with p85α SH3 with the same efficiency (10- to 10.5-fold increase in luciferase units compared to the negative control) (Fig. 4A). However, when the interaction of the NSP1N and NSP1C region with p85β SH2N-C was analyzed, a 55 to 60% reduction in luciferase activity was observed compared to the NSP1FL–p85β-SH2N-C interaction (Fig. 4B). Thus, overall results suggest that full-length rotavirus NSP1 is required for interaction with the p85β isomer, whereas the N-terminal region or C-terminal region of NSP1 is sufficient for interaction with the p85α isomer of the PI3K p85 subunit. Similar results were obtained with NSP1 of another wild-type RV strain, A5-13 (data not shown). Expression levels of all constructs for the mammalian two-hybrid assay were verified by Western blotting (Fig. 2C, 3C, and 4C). The functionality of full-length NSP1 in the mammalian two-hybrid vector was checked by its IRF3 degradation ability (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4.

Both N- and C-terminal regions of RV NSP1 can directly interact with p85α, but for efficient interaction with p85β, full-length RV NSP1 is needed. (A) The mammalian two-hybrid assay showed direct interaction of both N- and C-terminal RV NSP1 with the SH3 domain of the p85α subunit. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector constructs. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI). The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5). (B) The mammalian two-hybrid assay showed the importance of full-length RV NSP1 in direct interaction with the SH2N-C region of the p85β subunit. HEK293 cells were cotransfected with the indicated vector constructs. At 36 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and luciferase activity was measured with a dual-luciferase assay kit (Promega, WI). The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5). (C) Western blot data showed expression levels of full-length and truncated NSP1 constructs in the mammalian two-hybrid vector using polyclonal peptide antibody raised against both N-terminal and C-terminal parts of NSP1 (Thermo Scientific, IL). (D) Western blot data showed the functionality of full-length NSP1 in the mammalian two-hybrid vector by its IRF3 (Cell Signaling Inc., Danvers, MA) degradation ability. The blot was reprobed to analyze glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression (Cell Signaling Inc., Danvers, MA) as a loading control.

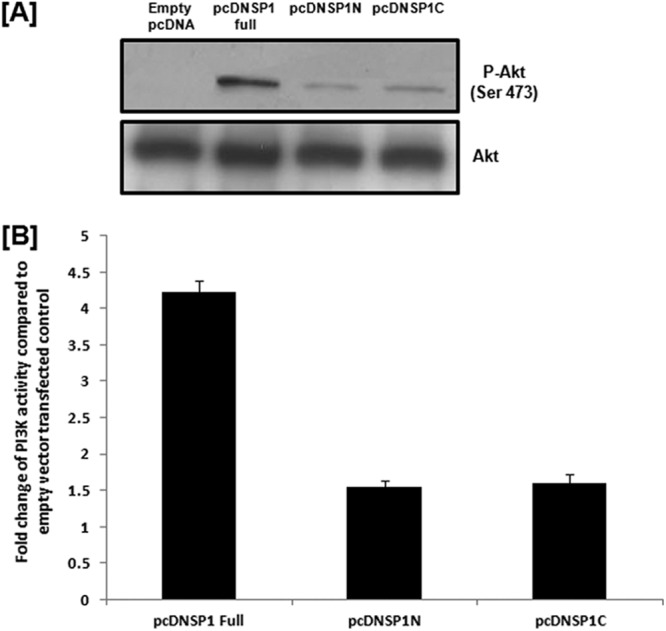

Full-length RV NSP1 is important for the efficient activity of PI3K.

We observed that both N-terminal and C-terminal regions of NSP1 could individually interact with p85α, but whether this interaction was sufficient to activate PI3K under cellular conditions was not clear. To assess this, we transfected HEK293 cells with either pcDNSP1, pcDNSP1N, pcDNSP1C, or the empty vector and analyzed the phosphorylation of Akt, which is a downstream effector of PI3K. The result showed that phosphorylation of Akt was significantly less in NSP1N- or NSP1C-transfected cells than in full-length-NSP1-transfected cells (Fig. 5A), confirming the importance of full-length NSP1 for efficient PI3K activation. The activity of PI3K was quantitated by using a PI3K activity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Millipore, MA) per the manufacturer's protocol. The PI3K activity assay revealed lower PI3K activity in pcDNSP1N- or pcDNSP1C-transfected cells than in pcDNSP1FL-transfected cells (∼3-fold) (Fig. 5B), corroborating Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 5A). This suggests that although the N-terminal or C-terminal domain of NSP1 can bind p85α, full-length NSP1 (NSP1FL) is required for efficient activation of PI3K.

Fig 5.

Full-length RV NSP1 is important for the efficient activity of PI3K. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with either empty pcDNA vector or pcDNSP1 full, pcDNSP1N, or pcDNSP1C, and at 36 h posttransfection, phosphorylation of Akt (Ser 473) was studied by Western blotting using anti-p-Akt (Ser 473) antibody (Cell Signaling Inc., Danvers, MA), which showed a larger amount of Akt phosphorylation in full-length-NSP1-transfected cells than in NSP1N- or NSP1C-transfected cells. The blot was reprobed to analyze total Akt expression (Cell Signaling Inc., Danvers, MA) as a loading control. (B) PI3K activity assay showed higher (about 3-fold) PI3K activity in full-length-NSP1-transfected cells than in pcDNSP1N- or pcDNSP1C-transfected cells at 36 hours posttransfection. The results here represent three independent experiments (P < 0.5).

Now, it is possible that in the cellular environment, interaction with both isomers (α and β) is important for activation of PI3K. Our data showed that NSP1FL is necessary for interaction with p85β (Fig. 4B), resulting in weak activation of PI3K by NSP1 mutants (NSP1N and NSP1C) (Fig. 5A and B). Colocalization of PI3K with GFP-FL NSP1, GFP-NSP1N, and GFP-NSP1C further confirmed weak colocalization in the case of mutant NSP1 compared to NSP1FL (see Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

Thus, this study confirmed direct interaction of NSP1 with both α and β isomers of PI3K regulatory subunit p85 and revealed the importance of full-length RV NSP1 and both α and β isomers of PI3K p85 for interaction between NSP1 and PI3K under cellular conditions which result in efficient PI3K activation. Our results indicate a probable conformational change of cellular PI3K after direct interaction with full-length rotavirus NSP1 that may lead to efficient activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by financial assistance from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, and the Program of Funding Research Centers for Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases (Okayama University-NICED, India) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. P. Bagchi (SRF) and S. Nandi (SRF) are supported by fellowships from CSIR, Government of India, and M. K. Nayak was supported by the Dr. D. S. Kothari Postdoctoral Fellowship from UGC, Government of India.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 5 December 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02479-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Yu J, Wjasow C, Backer JM. 1998. Regulation of the p85/p110alpha phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase. Distinct roles for the n-terminal and c-terminal SH2 domains. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30199–30203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Autret A, Martin-Latil S, Brisac C, Mousson L, Colbère-Garapin F, Blondel B. 2008. Early phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway activation limits poliovirus-induced JNK-mediated cell death. J. Virol. 82:3796–3802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ehrhardt C, Ludwig S. 2009. A new player in a deadly game: influenza viruses and the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Cell. Microbiol. 11:863–887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ehrhardt C, Wolff T, Pleschka S, Planz O, Beermann W, Bode JG, Schmolke M, Ludwig S. 2007. Influenza A virus NS1 protein activates the PI3K/Akt pathway to mediate antiapoptotic signaling responses. J. Virol. 81:3058–3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esfandiarei M, Boroomand S, Suarez A, Si X, Rahmani M, McManus B. 2007. Coxsackievirus B3 activates nuclear factor kappa B transcription factor via a phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/protein kinase B-dependent pathway to improve host cell viability. Cell. Microbiol. 9:2358–2371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee CJ, Liao CL, Lin YL. 2005. Flavivirus activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling to block caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death at the early stage of virus infection. J. Virol. 79:8388–8399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soares JA, Leite FG, Andrade LG, Torres AA, De Sousa LP, Barcelos LS, Teixeira MM, Ferreira PC, Kroon EG, Souto-Padrón T, Bonjardim CA. 2009. Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway early during vaccinia and cowpox virus infection is required for both host survival and viral replication. J. Virol. 83:6883–6899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shin YK, Liu Q, Tikoo SK, Babiuk LA, Zhou Y. 2007. Influenza A virus NS1 protein activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway by direct interaction with the p85 subunit of PI3K. J. Gen. Virol. 88:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hale BG, Batty IH, Downes CP, Randall RE. 2008. Binding of influenza A virus NS1 protein to the inter-SH2 domain of p85 suggests a novel mechanism for phosphoinositide 3-kinase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 283:1372–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang B, Spandau DF, Roman A. 2002. E5 protein of human papillomavirus type 16 protects human foreskin keratinocytes from UV B-irradiation-induced apoptosis. J. Virol. 76:220–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. zur Hausen H. 2002. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:342–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bagchi P, Dutta D, Chattopadhyay S, Mukherjee A, Halder UC, Sarkar S, Kobayashi N, Komoto S, Taniguchi K, Chawla-Sarkar M. 2010. Rotavirus nonstructural protein 1 suppresses virus-induced cellular apoptosis to facilitate viral growth by activating the cell survival pathways during early stages of infection. J. Virol. 84:6834–6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wei L, Hou L, Zhu S, Wang J, Zhou J, Liu J. 2011. Infectious bursal disease virus activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway by interaction of VP5 protein with the p85α subunit of PI3K. Virology 417:211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hua J, Mansell EA, Patton JT. 1993. Comparative analysis of the rotavirus NS53 gene: conservation of basic and cysteine-rich regions in the protein and possible stem-loop structures in the RNA. Virology 196:372–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.