Abstract

The present work demonstrates that Cy5.5 conjugated Fe3O4/SiO2 core/shell nanoparticles could allow us to control movement of human natural killer cells (NK-92MI) by an external magnetic field. Required concentration of the nanoparticles for the cell manipulation is as low as ~20 μg Fe/mL. However, the relative ratio of the nanoparticles loaded NK-92MI cells infiltrated into the target tumor site is enhanced by 17-fold by applying magnetic field and their killing activity is still maintained as same as the NK-92MI cells without the nanoparticles. This approach allows us to open alternative clinical treatment with reduced toxicity of the nanoparticles and enhanced infiltration of immunology to the target site.

Keywords: Fe3O4/SiO2 core/shell nanoparticles, Multifunctional nanoparticles, Magnetic field guided cell control, Natural killer cells, Tumor killing activity

1. Introduction

A variety of solid nanoparticles, such as metals, metal oxides and semiconductors nanoparticles, possess unique chemical and physical properties and have been widely utilized for biomedical applications, such as molecular imaging probes and nanomedicine [1–5]. However, many problems including chemical toxicity, biodegradability, and excretive clearance still remain to be solved before their clinical translation [6–8]. According to H. S. Choi et. al., for example, CdSe quantum dots with a hydrodynamic diameter above 5.5 nm cannot perfectly be eliminated by renal filtration, which leads to their prolonged retention time in the blood circulation [6]. Therefore, numerous nanoparticles with few tens nm in size maybeeasily accumulate in the non-targeted organs such as liver, spleen, kidneys, and lung, although we could well design the surface of the nanoparticles for specific targeting through various biomodification procedures [9–11]. This fact plus the potential toxic degradation components of the nanoparticles seriously limits the ability to advance nanoparticles to clinical applications [6–8]. Compared to nanoparticles, cells used for therapy like immunological cells have minimum cytotoxicity problems [12]. Especially, natural killer (NK) cells are well known a type of lymphocyte and play a central role in the tumor elimination from our body. However, it is often difficult to control the trafficking of these cells to target sites. The reason for this is not clear but may involved direct immune evasion strategies employed by cancer cells [13]. Nevertheless, clinical studies have demonstrated that increased tumor infiltration by NK cells correlate with improved prognosis and suggest that enhancement of NK cell infiltration could be a useful anti-tumor strategy [14]. The cell sorting method based on magnetic nanoparticles could be a promising alternative approach to resolve two main problems associated with the nanoparticles and cell based therapy. Because required concentration of the nanoparticles to control the cell could be very low and the cells incorporated with magnetic nanoparticles could then be isolated and attracted under the external magnetic field [15–19]. Whereas this technique has been used to not only enrich and detect circulating tumor cells in the blood stream but also delivery stem cells in injury site, its use for magnetic guided in-vivo delivery of immunological cells has been rarely reported so far. [17,18,20]

In this study, we demonstrate that magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles can control the movement of human natural killer (NK-92MI) cells using an external magnetic field. NK cells comprise a population of lymphocytes important in the recognition and killing of certain tumor targets [21,22]. Therefore, NK cells can be considered as one of the most ideal platforms for tumor therapy without a side effect compared to anticancer drug and radiation therapy. Here, we show in-vivo manipulation of the NK cells to the target site through the cell sorting method based on the magnetic nanoparticles with low concentrations, which were coated by silica layer and then conjugated with fluorescence organic dye for the in-vivo evaluation via fluorescence microscopy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles

Oleic acid coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles with 13 ± 2.5 nm in size were supplied from the Ocean NanoTech LLC. Concentration of the supplied Fe3O4 nanoparticles was determined as 22.9 Fe mg/mL by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis. Silica coating on the hydrophobic Fe3O4 nanoparticles was accomplished by modified reverse microemulsion procedure [23–26]. In a typical synthesis, 10, 20, 60, and 300 μL of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles were dispersed into 60 mL of cyclohexane, respectively. Triton-X100 (1.12 μL) as a nonionic surfactant, NH4OH (30wt% 152.8 μL), 1-octanol (400 μL), and tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS 200 μL) were then added into each of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles dispersed cyclohexane solution. When ammonia aqueous solution was injected into the cyclohexane solution, the solution was changed to turbid. Addition of 1-octanol led to clear the resulting solution that indicates successful building up of a reverse microemulsion [23–26]. The reaction mixtures were continuously stirred for 3 days at 600 rpm. The final product was dispersed into 60 mL of anhydrous EtOH after washing with ethanol through centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min. The final concentration of the Fe3O4/SiO2 core/shell nanoparticles was determined by ICP analysis.

2.2. Conjugation of fluorescence organic dye with Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles

Amine functional groups were introduced on the surface of the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles by trimethoxysilylpropyl modified polyethyleneimine (Gelest, MW = 1500-1800, 50% in isopropanol) through silane coupling reaction. Cy5.5-NHS ester was then covalently bonded to the PEI-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles. The resulting multifunctional nanoparticles with magnetic and fluorescence properties were purified by washing procedure with water solvent through centrifugation and then were utilized for in vitro and in vivo experiments via fluorescence microscopy and near infrared fluorescence imaging.

2.3. Human natural killer cell culture

Human activated NK cells, NK-92MI, were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). NK-92MI cells were cultured in the modified minimum essential Eagle’s medium (α-MEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-gulutamine, 2 mM nonessential amino acid (NEAA, Invitrogen), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 25% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen). NK-92MI cells were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C in log phase growth.

2.4. In-vivo monitoring movement of magnetic nanoparticle-labeled NK cells with the external magnetic field

The NK-92MI cells (1 × 105 cells/well) were seeded in a 96-well plate and centrifuged for 5 min at a low speed (1000 rpm). Cy5.5-labeled Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles (20 μg/mL) were added to each well and the plate was placed on a magnetic plate for 30 min in a CO2 incubator. After exposure of cells to the magnetic field, cells were collected into 15 mL tube and washed with media 3 times. Nanoparticles loaded NK cells (1 × 106 cells) were injected into tumor (GFP labeled RPMI8226 human B cell lymphoma) bearing NSG (immuno-deficient) mice. At the same time, Neodymium magnet (340 G/mm) was put adjacent to the tumor site and near infrared fluorescent images of labeled NK cells were captured every 30 s with the IVIS imaging systems.

2.5. In-vitro cytotoxicity assay of nanoparticle-labeled NK cells

RPMI8226 cells, which are well known as target for the NK cells, were loaded with calcein to serve as the NK target cells. One microliter of 10 mM calcein-AM solution (Invitrogen, C1430) was added to 106 target cells in 2 mL RPMI-1640/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 60 min. Target cells were then washed twice with RPMI-1640/10% FBS and resuspended in the same medium. Effector cells, the NK-92MI and nanoparticle-infected NK-92MI (5 and 20 μg Fe/ml) cells were mixed with 105 target cells at variable effector : target (E : T) ratios in a final volume of 200 μL using 96-well round plate. For enrichment of nanoparticle-infected NK-92MI cells, same number of NK cells (1 × 106) was tugged with external magnetic field and washed with media and then used as the effector cells for cytotoxicity assay. Each E : T ratio was tested in triplicate. After cell mixing, cell suspensions were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min and then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 4 h. The spontaneous release of calcein was determined by incubating loaded target cells in medium alone and maximal release was determined by adding 0.1% Triton-X to lyse all the target cells. After completion of incubation, plate was centrifuged at 300 g for 5 min, and 100 μL supernatant from each sample was transferred to a 96-well plate (Optiplate™ 96F, Perkin Elmer, Fremont, CA) and fluorescence was measured on a fluorometer (SpectraMax M3 Microplate Reader, Molecular Devices) at an excitation wavelength of 494 nm and emission wavelength of 517 nm. The median value for each triplicate was used in the calculation of cytotoxicity. Cytotoxicity, measured as percent specific release of calcein, was calculated using the following formula:

To analyze the percentage of lysed target cells by the NK-92MI cells, the nanoparticle-infected NK-92MI cells were mixed with GFP-labeled RPMI8226 cells at 3:7 ratios and incubated for 4 h. The percentage of GFP-positive RPMI8226 target cells was determined by flow cytometry.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of materials

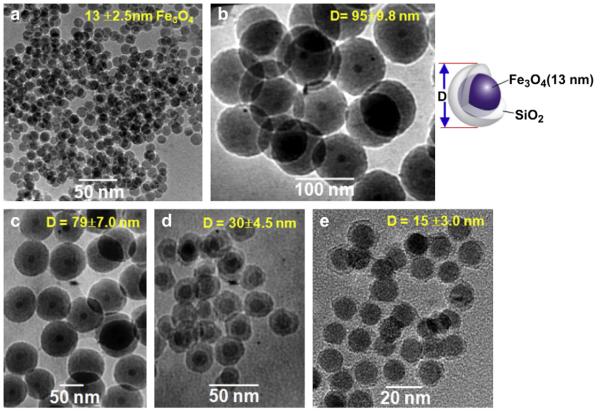

Fig.1 shows transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of bare Fe3O4 (13 ± 2.5 nm) and silica coated Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles. The silica thickness was fine controlled from 41.0 ± 7.3 to 1.0 ± 0.5 nm upon various reaction conditions as shown in Fig. 1(b)—(d). We find that concentration of the Fe3O4 is more important factor to control the silica thickness than other chemical species (e.g. water-to-surfactant ratio and TEOS). Namely, the SiO2 layer of 1.0 ± 0.5 nm was obtained from 300 μL (6.87 Fe mg) of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles whereas 41.0 ± 7.3 nm thickness of the SiO2 shell was achieved by adding the Fe3O4 nanoparticles of 10 μL (0.23 Fe mg) when the other conditions are the same. Such 1.0 nm thickness of the silica shell is a noticeable result because the average thickness of the silica layer prepared by the reverse microemulsion procedure has been reported as 10—70 nm [26,27]. After discovering Stöber method in 1968 [28], various core/shell nanostructures based on silica coating procedure have been developed upon increasing importance of multifunctional nanoparticles in the molecular imaging and nanomedicine. But silica coating has also led to a stability problem corresponding to the increased particle size and negative surface charge in water solvent with the neutral pH.[27,29,30]. Actually, Fig. S1(a) shows ζ potential results that surface charge of the Fe3O4/SiO2 dispersed into the water was systematically changed from −73.71 to −45.03 mV by decreasing silica thickness from 41.0 to 1.0 nm. Such the negative surface charge results in the oxygen anion of SiO2 surface under the solvent with neutral pH and thus could be enhanced in the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with the large thickness of the silica shell. Subsequently, the prepared Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with a diameter of 93 and 73 nm even precipitate out under only a few hours in water due to severe aggregation. However, the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with 1.0 nm silica thickness was mono-dispersed in solvent for few weeks without any aggregated form. As another disadvantage for the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with thick silica layer, interaction between the external magnetic field and core Fe3O4 could be weakened by increasing thickness of the silica shell due to a intrinsically diamagnetic property of SiO2. In fact, 1/T2 relaxivity of the core Fe3O4 was significantly reduced from 4500 to 360 m s−1 by increasing the silica thickness from 1.0 to 41.0 nm [31]. Therefore, a thin layer of silica coating is preferred for the biomedical application of the nanoparticles, and the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with 1.0 nm of the silica layer was further used to label the cells in this research.

Fig. 1.

TEM images of (a) bare Fe3O4 (13 nm) and Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with a silica thickness of (b) 41.0 ± 7.3 nm, (c) 32.8 ± 4.5 nm, (d) 10.2 ± 2.0 nm, and (e) 1.0 ± 0.5 nm.

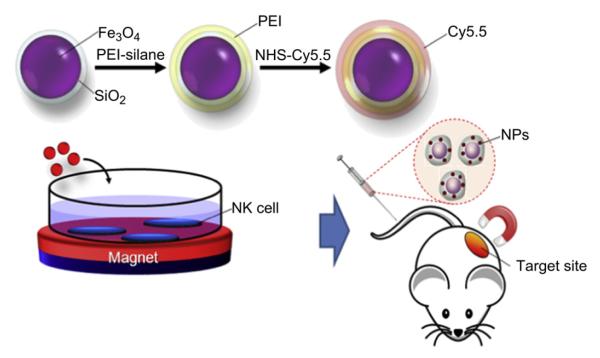

Scheme 1 represents the schematic illustration of preparation of the multifunctional nanoparticles, cellular uptake, and in-vivo experiment. In brief, the resulting Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with 1.0 nm of the silica layer were conjugated with trimethoxysilylpropyl modified polyethyleneimine (PEI) to increase the stability of the nanoparticles and to further modify the surface with amine functional groups, since the positive charge of the rich amines of the PEI could facilitate the cellular uptake of the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles [32,33]. From ζ potential results in Fig. S1(b), the surface charge of the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles was dramatically changed from negative to positive charge as +57.72 ~84.88 mV upon the silica shell thickness by conjugation with PEI. The difference of ζ potential charge between the bare Fe3O4/SiO2 and the PEI coated Fe3O4/SiO2 (PEI-Fe3O4/SiO2) was nearly constant as 130 mV regardless of changing silica thickness. This fact may imply that amine residues of the present PEI-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles are remained as the independently free form without electrostatic binding to each other. Because the ζ potential of the free PEI used in this study was approximately 130 mV. The resulting PEI-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles were remarkably stable under various hydrophilic solvents such as EtOH, water, and phosphate buffer saline (PBS). From the dynamic light scattering analysis, size of the PEI-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles in aqueous condition was determined as 38.4 ± 5.2 nm that differences in the size determined from TEM analysis comes from increasing hydrodynamic diameter via hydrophilic PEI chains in aqueous solution (Fig. S2). A fluorescence organic dye, Cy5.5-NHS ester, was then covalently coupled to the primary amine of the resulting PEI coated nanoparticles as shown in Scheme 1 [34,35]. Actually, cell tracking has been usually explored by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) system in the previous study thanks to the ability of the magnetic nanoparticles to shorten T2* relaxtion time [20]. However, high concentrations of the magnetic nanoparticles are typically needed to obtain the clear MR imaging that could seriously influence on viability and biological function of the cells through dissolving toxic Fe2+ species [36]. On the other hand, fluorescence microscopy is suitable for cell tracking even at a low concentration of fluorescence dye. Therefore magneto-fluorescent nanoparticles with dual modality allow us both cell control and their sensitive detection. Moreover, silica coating method could protect the core magnetic nanoparticles from external environment to further improve the biocompatibility of the resulting nanoparticles.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the nanoparticles preparation, cell uptake, and in-vivo experiment. The Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles are modified with PET-silane and fluorescent dyes. They are then incubated with NK cells. The nanoparticles loaded cells were injected into the mice through the tail vein and magnetically guided to deliver to the target site under an external magnetic field.

3.2. Nanoparticles transfection to NK cells and apoptosis assay

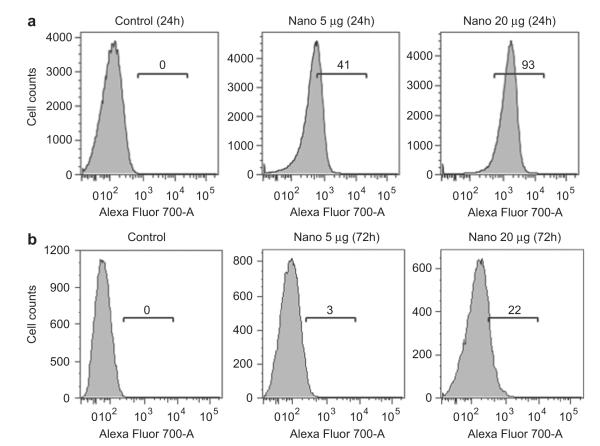

The final nanoparticles were magnetically transfected into the NK cells by an external magnetic field gradient of 159 gauss/mm, which was obtained from K&J Magnetics Inc., into the cell incubator for 30 min. The resulting NK cells were injected intravenously into GFP-labeled RPMI8226 human B cell lymphoma bearing NSG (immuno-deficient) xenograft nude mice and then were manipulated to the target tumor site by the external magnetic field. Fig. 2 (a) shows the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of the NK-92MI cells incubated with different concentrations of the Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles under the external magnetic field, where the magnet was applied for only 30 min and then removed during incubation for 24 h. After the incubation, the fraction of Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticle-transfected NK-92MI cells was 41% by the initial added concentration of 5 μg Fe/mL; this increased to 93.2% when 20 μg Fe/mL was used. Fluorescence intensity was also increased in the 20 μg Fe/mL group. According to this data, the increased concentration of Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles could give higher efficiency of transfection and also make single NK-92MI cell to uptake more nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 2(b), the ratio of the Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticle-positive NK-92MI cells was reduced to 22% after 72hrs incubation that the decreased concentration of the nanoparticles might have resulted from proliferation of or exocytosis by the NK-92MI cells.

Fig. 2.

FACS results of the NK cells magnetically transfected with 5 or 20 μg Fe/mL of the Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles after (a) 24 h and (b) 72hrs in which the external magnetic field gradient (159 gauss/mm) was applied only for 30 min and then removed from the NK-92MI cells. FACS data for the NK-92MI cells loaded with Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles after 72hrs incubation.

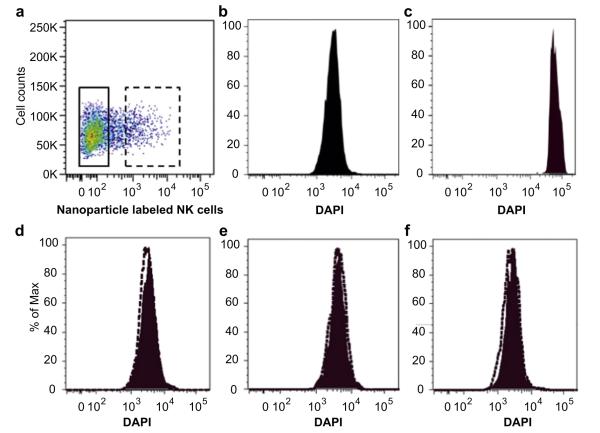

High concentration of Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles may cause apoptosis of NK-92MI cells after 3 days. To examine this hypothesis, we analyzed apoptotic cells after exposure cells with Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles through DAPI staining. As shown in Fig. 3, the NK-92MI cells loaded with concentration of a range from 5 to 20 μg Fe/mL have same FACS result with the nanoparticles free NK-92MI cells. It is indicating that even high concentrated nanoparticles of 20 μg Fe/mL could not induced apoptosis of the NK-92MI cells. Therefore, we used the Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles with an initial concentration of 20 μg Fe/mL for the following in-vivo experiment.

Fig. 3.

Apoptosis assays. (a) NK-92MI cells were transfected with nanoparticles and incubated in PBS containing 10 mg/mL of DAPI. (b) NK-92MI cells in complete media were used as negative control and (c) cells in serum-free culture condition were used as positive control. After transfection of (d) 5 μg, (e) 10 μg, (f) 20 μg nanoparticles, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACS Aria II cell sorter). Solid square is non-transfected NK-92MI cells. Dotted square is nanoparticle transfected cells.

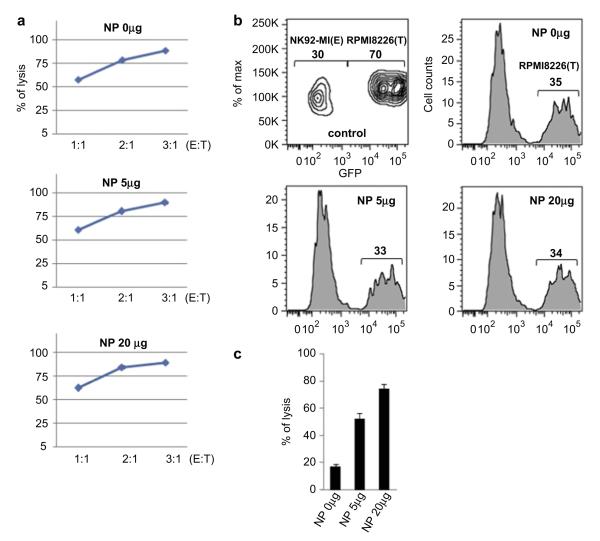

3.3. In-vitro killing activity of nanoparticles loaded NK cells and cytotoxicity assay

The next question is how about in vitro killing activity of the nanoparticles loaded NK-92MI cells? Actually, this is the most important and thus we studied on in vitro killing activity. Fig. 4 shows calcein release cytotoxocity assay of the nanoparticles loaded NK-92MI cells. RPMI8226 cells as targets (T) were stained with calcein and then we analyzed fluorescence intensity of the calcein released from the lysis of the target cells via attacking the NK cells as an effector (E) as shown in Fig. 4(a). Cytotoxic efficiency for the NK cells without the nanoparticle infection was increased upon increasing E:T ratio and the same results were obtained from the nanoparticles (5 μg and 20 μg Fe/mL) loaded NK-92MI cells. Fig. 4(b) shows lysis efficacy of the target cells (GFP-RPMI8226) after mixing with the three different NK-92MI cells loaded with three different doses of the nanoparticles (0, 5, and 20 μg Fe/mL). The relative ratios of the remaining target cells were decreased from 70% to 35, 33, and 34% due to the NK cell killing efficacy. It is indicating that the nanoparticles infected NK cells have almost the same killing activity with the control NK-92MI cells without the nanoparticles. One the other hand, the NK-92MI cells loaded with three different doses of the nanoparticles were magnetically collected and then we studied lysis efficacy of the resulting NK cells. As shown in Fig. 4(c), the transfected NK-92MI cells with the nanoparticles of 20 μg Fe/mL have the highest killing activity against to the target cells. Such result means that magnetic enrichment of the NK-92MI cells is proportionally enhanced by increasing concentration of the transfected nanoparticles. Based on the above results, we expect that the magnetically enriched NK-92MI cells could show good tumor treatment efficacy if enough NK cells are guided by a magnet to localize in the tumor.

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity assays. (a) NK-92MI cells (effector, E) were the transfected with nanoparticles (0, 5, and 20 μg Fe/mL) and then cytotoxicity was tested in calcein release assays using RPMI8226 cells (target, T) with different ratios of E. (b) Nanoparticles infected NK-92MI cells were mixed with GFP-labeled RPMI8226 cells at 3:7 ratio (control, without incubation) and the percentage of each cells was determined by flow cytometry after 4 h incubation. (c) The nanoparticles transfected NK-92MI cells were enriched by applying a magnetic field (159 gauss/mm) and then tested in calcein release cytotoxicity assays by using RPMI8226 cells as targets.

3.4. Tumor targeted NK cells delivery via applying magnetic field and in-vivo fluorescence imaging

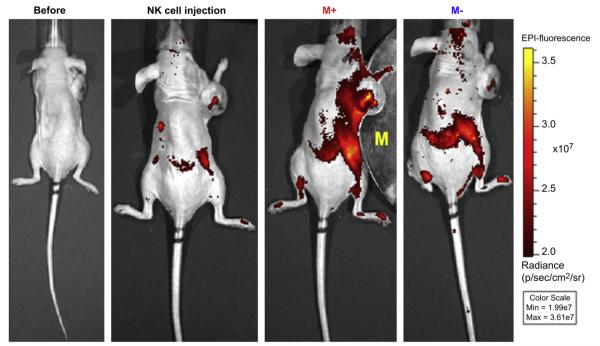

Magnetic guided delivery of the NK cells incorporated with Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles to the tumor site was evaluated by in-vivo near infrared fluorescence imaging. As shown in Fig. 5 (b), weak Cy5.5 fluorescence signal of NK cells were observed from the spleen and the necrosis region of the tumor at the time of injection of the nanoparticle loaded cells. After placing a magnet (340 gauss/mm) adjacent to the tumor, fluorescence intensity in the tumor and around the magnet were remarkably increased within 10 min as shown in Fig. 5(c), because of the amplified delivery of the number of the NK cells attracted by the external magnetic field. When the magnet was removed, fluorescence signal was quickly disappeared from the tumor site within few minutes due to the blood stream as shown in Fig. 5(d).

Fig. 5.

In-vivo fluorescence images of the GFP-labeled RPMI8226 human B cell lymphoma xenograft (n = 3 for each group). (a) Before and (b) after injection (5 min) of the nanoparticle loaded NK-92MI cells, (c) after applied (for 10 min) and (d) removed a magnet (340 gauss/mm).

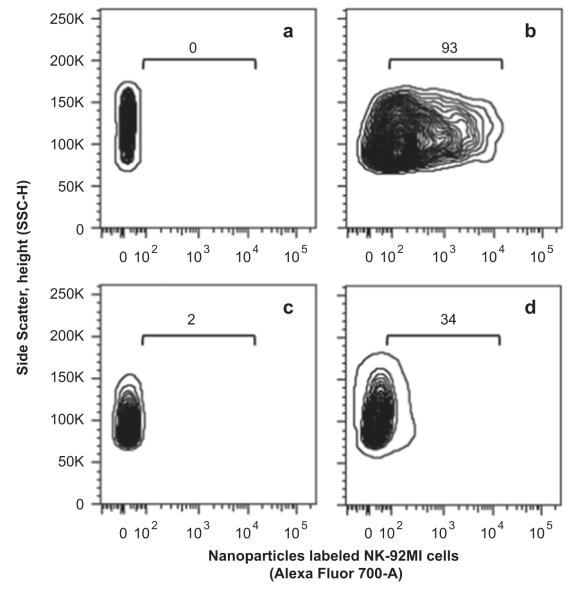

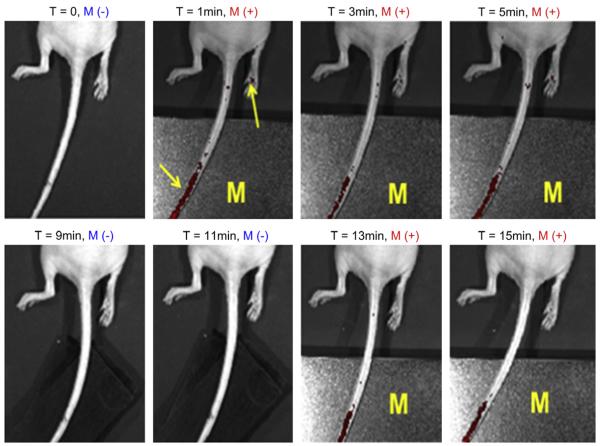

One issue needs to be noted here that the conventional magnet was used to guide the accumulation of the labeled NK cells in the subcutaneous tumor model in this research. Considering the movement of the magnetic nanoparticles labeled NK cells could be a one direction and inevitably accumulate to the skin of the animal, it would be very important to further evaluate of the labeled NK cells for targeting deep tumor tissues under the magnet and FACS analysis could give to us that information. FACS analysis of the harvested tumor tissues revealed that the quantity of the NK-92MI cells infiltrating into the tumor site increased from 2% to 34% by applying the magnetic field for 30 min as shown in Fig. 6 (c) and (d), where the NK-92MI cells incorporated with the 93% of Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles of 20 μg Fe/mL (initially added concentration) were injected into the GFP-labeled RPMI8226 human B cell lymphoma mice as shown in Fig. 6(a) and (b). Of note, the relative ratio of the NK-92MI cells infiltrated into the target tumor site was enhanced by 17-fold. According to the cell rolling theory, the endothelial cells near the tumor site express certain adhesive molecules (e.g. p-selectin) which facilitate the NK cells to roll and infiltrate into the tumor cells [37]. However, such adhesive force may not strong enough to achieve high accumulation of the NK cells into the deep tumor tissues. For the nanoparticles labeled NK cells, infiltration probability into the deep tumor site could be remarkably improved by increasing adhesion time of the NK cells to the tumor cells via applying a magnetic field. Therefore, such an enhancement of the relative FACS ratio could come from the NK cells accumulated in the deep tumor tissue. Fig. 7 shows the real time fluorescence images for a response of the nanoparticles loaded NK-92MI cells under the external magnetic field. It can be clearly seen that the NK cells were collected on the tail vein by the external magnet and vanished by blood stream after the magnet removal. This result indicates at withdrawing magnet we can freely control the NK cells to the predetermined site by using the magnetic nanoparticles and magnetic field.

Fig. 6.

Result of FACS analysis for the NK-92MI cells infiltrated into the tumor site with and without the external magnet (340 gauss/mm). Prepared NK-92MI cells (a) before and (b) after Cy5.5-Fe3O4/SiO2 magneto-transfection. (c) Tumor (GFP-labeled RPMI8226 human B cell lymphoma) infiltrated nanoparticle labeled NK-92MI cells (GFP-Cy5.5+) without magnet and (d) with magnet.

Fig. 7.

Time resolved in-vivo fluorescence images for manipulation of the nanoparticles loaded NK-92MI cells upon the magnetic field. Where M represents the magnet and M(−)/M(−) means applying/withdrawing the magnet (565 gauss/mm).

We tried to maintain the magnet on the tumor site to achieve the tumor shrinkage after the use of the nanoparticles loaded NK cells injection and external magnet but it was very hard to attach the magnet on tumor skin of very active live mice for a long time. However, we believe that the magnetically enriched NK cells could be well working on the tumor site because its killing activity was well maintained as shown in Fig. 4. In the near future, we will try again as bigger animal model such as rabbit, dog, and pig.

4. Conclusions

We can freely control movement of the NK-92MI cells incubated with the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles by driving the magnetic field. Typically, relative ratio of the NK-92MI cells infiltrating into the tumor site was increased by 17-fold through the magnetic field-induced moving control method. Especially, concentration of the nanoparticles to manipulate the NK cells was only 20 μg Fe/mL which is remarkably lower than few hundred μg Fe/mL and few mg Fe/mL scale for the conventional in-vitro and in-vivo experiments to evaluate MRI monitoring, drug delivering, and magnetic hyperthermia therapy [31], [35], [38], [39] This result allows us to explore a new approach to the cell based therapy. With further improvement in the magnetic field control technology and using the MRI system, it is expected that accurate transmission of the immunological cells to the 3-dimensional target site without surgical treatment. One of the most prosmising advantages in our approach is that it may significantly diminish the problems associated with chemical toxicity due to significantly low concentration of the nanoparticles. This approach could greatly facilitate future biomedical applications of the nanoparticles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by NCI/NIH R21 CA121842, NIH R41 CA137960, NCI Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence Grant U54 CA119367, R33HL089027, R01EB009689. E. —S. Jang thanks research fund (2011-0024700) of the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MEST).

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary material Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.041.

References

- [1].Gao J, Chen K, Miao Z, Ren G, Chen X, Gambhir SS, et al. Affibody-based nanoprobes for HER2-expressing cell and tumor imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jokerst JV, Miao Z, Zavaleta C, Cheng Z, Gambhir SS. Affibody-functionalized gold—silica nanoparticles for Raman molecular imaging of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Small. 2011;7:625–33. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Smith BR, Cheng Z, De A, Rosenberg J, Gambhir SS. Dynamic visualization of RGD-quantum dot binding to tumor neovasculature and extravasation in multiple living mouse models using intravital microscopy. Small. 2010;6:2222–9. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Huang J, Bu L, Xie J, Chen K, Cheng Z, Chen X. Effects of nanoparticle size on cellular uptake and liver MRI with polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated iron oxide nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2010;4:7151–60. doi: 10.1021/nn101643u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gao J, Chen K, Xie R, Xie J, Lee S, Cheng Z, et al. Ultrasmall near-infrared noncadmium quantum dots for in vivo tumor imaging. Small. 2010;6:256–61. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Ipe BI, et al. Renal clearance of quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1165–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bhabra G, Sood A, Fisher B, Cartwright L, Saunders M, Evans WH, et al. Nanoparticles can cause DNA damage across a cellular barrier. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:876–83. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mahmoudi M, Azadmanesh K, Shokrgozar MA, Journeay WS, Laurent S. Protein-nanoparticle interactions: opportunities and challenges. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5610–37. doi: 10.1021/cr100440g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Schipper ML, Lyer G, Koh AL, Cheng Z, Ebenstein Y, Aharoni A, et al. Particle size, surface coating, and PEGylation influence the biodistribution of quantum dots in living mice. Small. 2009;5:126–34. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Huang J, Xie J, Chen K, Bu L, Lee S, Cheng Z, et al. HSA coated MnO nanoparticles with prominent MRI contrast for tumor imaging. Chem Commun. 2010;46:6684–6. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01041c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Orr MT, Lanier LL. Natural killer cell education and tolerance. Cell. 2010;142:847–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Höglund P, Brodin P. Current perspectives of natural killer cell education by MHC class I molecules. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:724–34. doi: 10.1038/nri2835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Groh V, Wu J, Yee C, Spies T. Tumour-derived soluble MIC ligands impair expression of NKG2D and T-cell activation. Nature. 2002;419:734–48. doi: 10.1038/nature01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ishigami S, Natsugoe S, Tokuda K, Nakajo A, Che X, Iwashige H, et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral natural killer cells in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:577–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Yoon TJ, Yu KN, Kim E, Kim JS, Kim BG, Yun SH, et al. Specific targeting, cell sorting, and bioimaging with smart magnetic silica core—shell nanomaterials. Small. 2006;2:209–15. doi: 10.1002/smll.200500360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Amendola V, Meneghetti M, Granozzi G, Agnoli S, Polizzi S, Riello P, et al. Topdown synthesis of multifunctional iron oxide nanoparticles for macrophage labelling and manipulation. J Mater Chem. 2011;21:3803–13. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Galanzha EI, Shashkov EV, Kelly T, Kim JW, Yang L, Zharov VP. In vivo magnetic enrichment and multiplex photoacoustic detection of circulating tumour cells. Nat Nanotechnol. 2009;4:855–60. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Riegler J, Allain B, Cook RJ, Lythgoe MF, Pankhurs QA. Magnetically assisted delivery of cells using a magnetic resonance imaging system. J Phys D: Appl Phys; 2011;44:055001. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pan Y, Long MJC, Li X, Shi J, Hedstrom L, Xu B. Glutathione (GSH)-decorated magnetic nanoparticles for binding glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusion protein and manipulating live cells. Chem Sci. 2011;2:945–8. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Riegler J, Wells JA, Kyrtatos PG, Price AN, Pankhurst QA, Lythgoe MF. Targeted magnetic delivery and tracking of cells using a magnetic resonance imaging system. Biomaterials. 2010;31:5366–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 2008;112:461–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fujisaki H, Kakuda H, Shimasaki N, Imai C, Ma J, Lockey T, et al. Expansion of highly cytotoxic human natural killer cells for cancer cell therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4010–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mahmoudi M, Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Boutry S, Simchi A, Journeay WS, et al. Effect of nanoparticles on the cell life cycle. Chem Rev. 2011;111:253–80. doi: 10.1021/cr1001832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yi DK, Lee SS, Papaefthymiou GC, Ying JY. Synthesis and applications of magnetic nanocomposite catalysts. Chem Mater. 2006;18:614–9. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang Y, Jing L, Yu X, Yan D, Gao M. Coating aqueous quantum dots with silica via reverse microemulsion method: toward size-controllable and robust fluorescent nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2007;19:4123–8. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Koole R, Schooneveld MM, Hilhort J, Donegá CM, Hart DC, Blaaderen A, et al. On the incorporation mechanism of hydrophobic quantum dots in silica spheres by a reverse microemulsion method. Chem Mater. 2008;20:2503–12. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kim J, Kim HS, Lee N, Kim T, Kim H, Yu T, et al. Multifunctional uniform nanoparticles composed of a magnetite nanocrystal core and a mesoporous silica shell for magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging and for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8438–41. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Stöber W, Fink A, Bohn E. Controlled growth of monodisperse silica spheres in the micron size range. J Colloid Int Sci. 1968;26:62–9. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lu F, Wu SH, Hung Y, Mou CY. Size effect on cell uptake in well-suspended, uniform mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:1408–13. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bagwe BP, Hilliard LR, Tan W. Surface modification of silica nanoparticles to reduce aggregation and nonspecific binding. Langmuir. 2006;22:4357–62. doi: 10.1021/la052797j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cha EJ, Jang ES, Sun IC, Lee IJ, Ko JH, Kim YI. Development of MRI/NIRF ‘activatable’ multimodal imaging probe based on iron oxide nanoparticles. J Control Release. 2011;155:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kievit FM, Veiseh O, Bhattarai N, Fang C, Gunn JW, Lee D, et al. PEI-PEG-chitosancopolymer-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for safe gene delivery: synthesis, complexation, and transfection. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19:2244–51. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200801844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Arsianti M, Lim M, Marquis CP, Amal R. Assembly of polyethylenimine-based magnetic iron oxide vectors: insights into gene delivery. Langmuir. 2010;26:7314–26. doi: 10.1021/la9041919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lee S, Cha EJ, Park K, Lee SY, Hong JK, Sun IC, et al. A near-infrared-fluorescence-quenched gold-nanoparticle imaging probe for in vivo drug screening and protease activity determination. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;120:2846–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Cho YS, Yoon TJ, Jang ES, Hong KS, Lee SY, Kim OR, et al. Cetuximab-conjugated magneto-fluorescent silica nanoparticles for in vivo colon cancer targeting and imaging. Cancer Lett. 2010;299:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nel AE, Mädler L, Velegol D, Xia T, Hoek EMV, Somasundaran P, et al. Understanding biophysicochemical interactions at the nano—bio interface. Nat Mater. 2009;8:543–57. doi: 10.1038/nmat2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].McEver RP, Zhu C. Rolling cell adhesion. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:363–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Lee JH, Huh YM, Jun YW, Jang JT, Song HT, Kim S, et al. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nat Med. 2007;13:95–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lee JH, Jang JT, Choi JS, Moon SH, Noh SH, Kim JW, et al. Exchange-coupled magnetic nanoparticles for efficient heat induction. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6:418–22. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.