Abstract

Statins are used to control elevated cholesterol or hypercholesterolemia, but have previously been reported to have antiviral properties.

Aims

To show efficacy of statins in various influenza virus mouse models.

Materials & methods

BALB/c mice were treated intraperitoneally or orally with several types of statins (simvastatin, lovastatin, mevastatin, pitavastatin, atorvastatin or rosuvastatin) at various concentrations before or after infection with either influenza A/Duck/ MN/1525/81 H5N1 virus, influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus, influenza A/ Victoria/3/75 H3N2 virus, influenza A/NWS/33 H1N1 virus or influenza A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus.

Results

The statins administered intraperitoneally or orally at any dose did not significantly enhance the total survivors relative to untreated controls. In addition, infected mice receiving any concentration of statin were not protected against weight loss due to the infection. None of the statins significantly increased the mean day of death relative to mice in the placebo treatment group. Furthermore, the statins had relatively few ameliorative effects on lung pathology or lung weights at day 3 and 6 after virus exposure, although mice treated with simvastatin did have improved lung function as measured by arterial saturated oxygen levels in one experiment.

Conclusion

Statins showed relatively little efficacy in any mouse model used by any parameter tested.

Keywords: anti-inflammatory, atorvastatin, BALB/c mouse, influenza virus, lovastatin, mevastatin, pitavastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin, statin

There is much concern about the impact of future influenza pandemics on the health of the world’s population [1–3], due, in part, to the recently reported outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza occurring in southeast Asia, the ability of the influenza viruses to transfer through bird populations to humans [4–6] and the 2009 pandemic caused by the H1N1pdm09 viruses [7]. Thus, much research is being carried out to develop effective anti-influenza drugs that are capable of being mass produced, which would enable the health systems of the world to cope with a massive, debilitating outbreak of influenza disease [8]. Several drugs have been approved for the treatment of influenza virus infection in the clinic, including the M2 ion channel inhibitors, amantadine and rimantadine, and the influenza virus neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors, oseltamivir and zanamivir [9]. However, some recent studies have indicated that avian influenza H5N1 viruses are resistant to amantadine and rimantadine [10], that zanamivir and oseltamivir are much less effective against the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus when experimental infections were induced in mice [11], and that oseltamivir has significantly reduced efficacy when it is used to treat mice infected with more virulent influenza A H5N1 viruses [12]. Other studies have shown that the H1N1pdm09 viruses are also resistant to amantadine [13,14] and to a lesser extent to the NA inhibitors [15,16]. Therefore, the likelihood for development of resistance, especially with the projected widespread use of the NA inhibitor, oseltamivir, during a pandemic, raises further concerns regarding the utility of the current NA inhibitors [17]. These concerns emphasize the continual need for additional antiviral agents to treat infections caused by avian H5N1 viruses and by strains of seasonal influenza viruses causing pandemics.

Severe influenza disease has been shown to be primarily mediated by a host’s hyperinflammatory response resulting in the so-called ‘cytokine storm’ [18] and leading to acute respiratory distress and pneumonia [19]. Thus, there is a great need to develop novel therapeutics to facilitate treatment of the hyperimmune responsiveness, to supplement the efficacy of existing antiviral drugs and to fill the ‘vaccination gap’ due to the time needed to develop the vaccines and make them globally available once an influenza strain has been recognized as causing major disease.

There are a number of US FDA-approved drugs that could be re-purposed to improve outcome and survival in influenza, and other serious systemic infections, due to their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. Agents such as metformin, gemfibrozil, simvastatin and pioglitazone have all been reported to have some positive effect on influenza infections, based on data from retrospective and other types of clinical studies in humans [20–23], or from experimental infections in mice [24–27]. Celecoxib and mesalazine, two approved anti-inflammatory agents, have also been promoted as possible agents to reverse the hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines produced during severe influenza H1N1pdm09 virus infections [28]. In addition, it has been found that treatment with zanamivir, celecoxib and mesalazine significantly decreased the mortality in mice infected by H5N1 when compared with zanamivir alone [25]. This has lead to the development of the hypothesis that clinically-approved agents, such as those described above, alone or in combination with antiviral agents, could lead to beneficial treatment effects for severe influenza infections in humans [29–32].

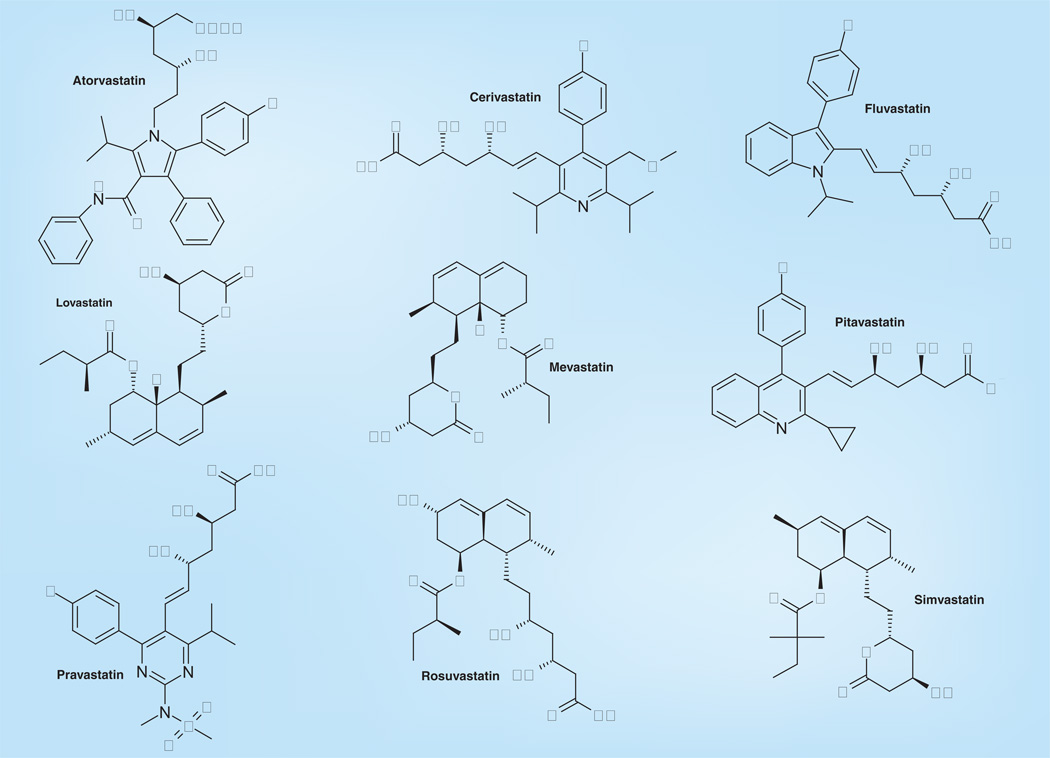

The basis of this hypothesis is that the hyperimmune response (i.e., excessive inflammation) displayed by patients with severe influenza disease (including the manifestation of pneumonia and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome) could be ameliorated by properly regulating (usually downregulating) molecular targets in various metabolic pathways associated with the induction of inflammatory processes. Anti-inflammatory and immune-modulatory agents such as statins [33,34] have been suggested as potentially beneficial agents for treating influenza infections [8,32,35,36]. However, some of the studies in humans have problems, including the fact that they are often observational retrospective studies, and that they are often confounded by the fact that many patients are not only trying to control their cholesterol by pill, but also by diet. Thus, the studies may be biased by having a preponderance of healthy individuals enrolled with better lifestyles than the general public and by having more subjects likely to be immunized with the influenza vaccine [37]. An exception to this was the study of Vandermeer et al. that seemed to be controlled for influenza vaccination in the data analysis, which also probably controlled for healthy user bias [36]. Fedson postulated that because statins (Figure 1 & Table 1) have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that might markedly affect the acute lung injury, they could be used to treat influenza virus infections [8]. Simvastatin is a synthetic derivative of a fermentation product of Aspergillus terreus and a member of the statin class of pharmaceuticals. It has been shown to both dramatically reduce the response of human pulmonary artery endothelial cells to thrombin-induced endothelial barrier and cytoskeletal dysfunction [38] and to reduce the induction of proinflammatory cytokines by C-reactive protein in a human umbilical vein endothelial cell inflammatory model. The drug also induced pronounced endothelial barrier protection in a murine model of acute lung injury [39]. Terblanche et al. further suggested that statins might be useful against infectious diseases that are characterized by hyperinflammatory responses, such as influenza [40]. It has been proposed that in cell culture, statins may act to inhibit influenza virus replication by blocking the influenza virus-mediated activation of RhoAGTPase protein in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells [41].

Figure 1.

Structures of various statins.

Table 1.

The two main groups of statins.

| Statin | Brand name | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| Group I | ||

| Atorvastatin | Lipitor®, Torvast® | Synthetic |

| Cerivastatin | Lipobay®, Baycol® (withdrawn from the market in August 2001 due to the risk of serious rhabdomyolysis) | Synthetic |

| Fluvastatin | Lescol®, Lescol XL® | Synthetic |

| Rosuvastatin | Crestor® | Synthetic |

| Pitavastatin | Livalo®, Pitava® | Synthetic |

| Group II | ||

| Lovastatin | Mevacor®, Altocor®, Altoprev® | Fermentation derived, naturally occurring compound, found in oyster mushrooms and red yeast rice |

| Mevastatin | – | Naturally occurring compound, found in red yeast rice |

| Pravastatin | Pravachol®, Selektine®, Lipostat® | Fermentation derived |

| Simvastatin | Zocor®, Lipex® | Fermentation derived (simvastatin is a synthetic derivate of a fermentation product) |

It was, therefore, of interest to determine if statin drugs would significantly impact the lethality of various influenza virus infection in BALB/c mice using a variety of dosing regimens. In addition, a statin was used in combination with an experimentally proven anti-influenza agent, favipiravir [42–45].

Materials & methods

Viruses & cells

Influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus was a gift from Robert G Webster, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Memphis, TN, USA). Influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) virus was initially provided by Kenneth W Cocharn at University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) virus was obtained from the CDC (Atlanta, GA, USA). All the viruses used in the experiments were passaged through MDCK cells (ATCC) at least once to prepare pools. Influenza A/ Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus was passaged once in MDCK cells and twice through mice to adapt it to the animals. Influenza A/ Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus was passaged once through embryonated eggs, once in MDCK cells and seven times in mice. Influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) was passaged nine times in MDCK cells and a pool prepared and pre-titrated in mice prior to use in the experiment. The H1N1pdm09 strain was originally obtained from Elena Govorkova (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital). It has been designated as influenza A/CA/04/09 virus (SJ#175190) and was adapted to mice by Natalia A Ilyushina (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital). Pools of each were titrated in MDCK cells before use. The cells were grown in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Logan, UT, USA) and 0.18% sodium bicarbonate with no antibiotics in a 5% CO2 incubator. Viral propagation was done in MDCK cells in MEM, 0.18% sodium bicarbonate, 10 units of trypsin/ml and 1.0 µg ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)/ml.

All experiments using influenza A/Vietnam/ 1203/2004 H5N1 virus were conducted under biosafety level 3 containment [101] including enhancements required by the US Department of Agriculture and Select Agent Program [102].

Test compounds

Simvastatin (Lipex®, molecular formula: C25H38O5; molecular weight: 418.57) in 80 mg-tablet form was obtained from a local pharmacy and the unformulated version from LKT Laboratories, Inc. (St Paul, MN, USA). The tablets were ground up with mortar and pestle. Unformulated lovastatin, atorvastatin, mevastatin, pitavastatin and rosuvastatin were obtained from LKT Laboratories, Inc. Favipiravir (T-705) was provided by Y Furuta of Toyama Chemical Co., Ltd. (Toyama, Japan). All preparations used for in vivo animal studies were suspended in 0.4% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) or in physiologically sterile saline (PSS), and stored at 4°C until they were used.

Animals

Specific pathogen-free female 17–21 g BALB/c mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA) for this study. They were maintained on Wayne Lab Blox and fed with standard mouse chow and tap water ad libitum. The BALB/c mice were quarantined for 4–5 days prior to use. The animal studies were carried out in a certified bio-safety level 3+ animal facility. Animal procedures complied with the guidelines set forth by US Department of Agriculture and the Utah State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

These studies were conducted in accordance with and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Utah State University. The work was done in the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited Laboratory Animal Research Center of Utah State University. Initial accreditation was granted on 10 February 1986 and has been maintained to the present time (last renewal: 24 September 2011). The Animal Welfare Assurance Number is A3801–01 and was last reviewed by the NIH on 8 June 2011 in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2010 Edition) and expires on 28 February 2014.

General animal experimental design

The BALB/c mice were anesthetized with a 0.1 ml intraperitoneal (ip.) injection of 50 mg/kg of ketamine plus xylazine at 5 mg/kg. An influenza A virus was then administered intranasally in a volume of 0.05–0.09 ml. The infection inoculation equated to a lethal dose from 60 to 100% (LD90) challenge dose, depending on the experiment. A summary of the treatment regimens used is shown in Table 2. Generally, groups of 10–20 mice were administered a dose of a particular statin either ip. or orally (p.o.) at various doses for variable lengths of time using prophylactic and/or therapeutic treatment regimens. Treatment dosing volumes used were generally 0.1 ml for each route of administration. For p.o. treatments, mice were lightly anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg) plus xylazine (5 mg/kg) prior to administering drug by oral gavage. Statins were delivered in 0.4% CMC regardless of the route of administration. The placebo (0.4% CMC) was administered in parallel to the statin treatments to 10–30 infected mice depending on the experiment. For one experiment, mice were treated with favipiravir p.o. Groups of five mice were also treated with a statin, but were not challenged with the virus. These groups constituted the toxicity controls for the experiment. Both drug-treated infected mice and placebo-treated controls were observed daily for death for up to 21 days post virus exposure. Generally, mice were weighed every day or every other day to determine the average weight change of the group and were observed for clinical signs of distress (see adverse events below). Animals that lost more than 30% of their initial body weight were humanely euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and the day of euthanization was designated as the day of death due to infection. Owing to virus titrations, lung scoring and lung weight determinations, five mice from each group were sacrificed on days 1, 3, 6 and or 9 after virus exposure, although most commonly on days 3 and 6 post virus exposure. Parameters for determining the effects of treatment included the prevention of death through day 14 or day 21 post virus infection, inhibition of lung consolidation (lung score and lung weight), lessening of lung virus titers and assessment of lung function by monitoring saturated oxygen levels (SaO2).

Table 2.

Summary of statin treatment regimens used.

| Study | Reference figure or table |

Treatment | Dose | Route of administration |

Treatment schedule | Influenza virus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Figure 2 | Simvastatin | 20, 10 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | A/NWS/33 H1N1 |

| 2 | Figure 3 | Simvastatin | 20, 10, 5 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d.: days -1, 0 | A/Victoria/3/75 H3N2 |

| q.d.: days -1, 0, 1, 2 ,3 | ||||||

| 3 | Figure 4 | Simvastatin | 20, 10, 5 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d.: -24 h, + 15 min | A/Duck/MN/1525/81 H5N1 |

| 4 | Figure 5 | Simvastatin | 20, 10 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d.: -24 h, + 15 min | A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 |

| q.d.: -24 h, + 15 min, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h | ||||||

| 5 | Figure 6 | Simvastatin | 10 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d. × 8, beg. -14 days | A/Duck/MN/1525/81 |

| Table 3 | q.d. × 8, beg. -20 days | |||||

| 6 | Figure 7 | Rosuvastatin | 20, 10, 5 mg/kg/day | ip. | q.d. × 2, q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 |

| 7 | Figure 7 | Atorvastatin | 20, 10, 5 mg/kg/day | p.o. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 |

| 8 | Figure 8 | Simvastatin | 15, 8.6 mg/kg/day | p.o. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 |

| Lovastatin | 32.9, 18.8 mg/kg/day | p.o. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | |||

| Pitavastatin | 12, 6.9 mg/kg/day | p.o. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | |||

| Mevastatin | 15.4, 8.8 mg/kg/day | p.o. | q.d. × 2, beg. -4 h; q.d. × 5, beg. -4 h | |||

beg.: Beginning; ip.: Intraperitoneal; q.d.: Once a day; p.o.: Orally.

Test compound toxicity determination

For each statin, a dose range finding experiment was carried out to determine the maximum tolerated concentration that could be used. Three mice were used per treatment group. Toxicity controls were run in parallel at each drug dose, weights were taken prior to the start of each treatment and the animals were observed for overt signs of toxicity and death for 21 days. Adverse events for which observations were made included ruffling of fur, lethargy, paralysis, incontinence, repetitive circular motion and aggression. Mice were also weighed every day from 24 h prior to virus infection to days 14 or 21 post virus exposure. Healthy controls were also included in each study involving SaO2 determinations; these animals were weighed along with the toxicity controls. Sometimes, three healthy controls were killed along with the infected mice to provide background lung data.

Lung score/lung weight determinations

Lungs were scored based on their surface appearance. Lungs were assigned a score ranging from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating that the lungs looked normal and 4 denoting that the entire surface area of the lung was inflamed and showed plum colored lung discoloration [46]. Significant differences in lung scores were determined by a Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s pairwise comparison post-tests. ANOVA was used to determine significant differences in lung weights. Follow-up pairwise comparisons were made by Newman–Keuls post-tests.

Lung virus titer determinations

Lung virus titers were analyzed from mice sacrificed on days 3 and 6 post virus exposure. Each mouse lung was collected, homogenized and the samples were assayed in triplicate for viral titration in MDCK cells by cytopathic effect assay as described previously [47]. The titers (CCID50 values) were calculated using the Reed-Muench method [48]. Significant differences were detected by ANOVA. Subsequent pairwise comparisons were made by Newman–Keuls post-tests.

Arterial oxygen saturation determinations

SaO2 was determined with a Biox 3800 pulse oximeter (Ohmeda, Louisville, OH). The ear probe attachment was used, with the probe placed on the thigh of the mouse. Readings were made after 30 s of stabilization for each animal. This method has been described in detail [49]. All SaO2 determinations were made on days 3–11 after virus exposure. The animals that died of obvious influenza virus infection during the experiment were assigned an SaO2 value of 75%, since the values normally do not drop below this level [49]. Significant differences were detected by ANOVA. Subsequent pairwise comparisons were made by Newman–Keuls post-tests.

Survival & weight change analysis

Mice were weighed in groups prior to treatment and then every day thereafter to determine the average weight change for all animals in each treatment group. Weights were expressed as group averages for each day and evaluated for statistical significance by the two-way ANOVA. When statistical significance was achieved, significant differences between two treatment groups were analyzed by Bonferroni’s pairwise comparison tests.

Survival analyses were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier graphical method and a Logrank test. When significant differences among the treatment groups were observed, pairwise comparisons of survivor curves (PSS vs any treatment) were analyzed by the Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test, and the relative significance was adjusted to a Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold for the number of treatment comparisons carried out. Mean day of death (deaths caused by disease) was calculated and analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s posttest for evaluating the significant pairwise comparisons. The live mice per total mice ratios in each treatment group were compared by contingency table analyses followed by pairwise comparisons using Fisher’s exact test. Hazard ratios (HRs), which compare how rapidly groups of treated mice are dying relative to untreated control groups of mice, were determined by the Mantel–Haenszel tests as part of the survival analysis program used above (GraphPad Prism® for MAC v5).

Histopathology

From selected groups of BALB/c mice infected and treated as described above, the lungs were removed from mice and were formalin-fixed. Three-to-five lungs from each treatment group were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain and evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist for histopathological changes.

Results

Evaluation of simvastatin on death & weight change of BALB/c mice infected with a lethal dose of influenza A/NWS/33 H1N1 virus

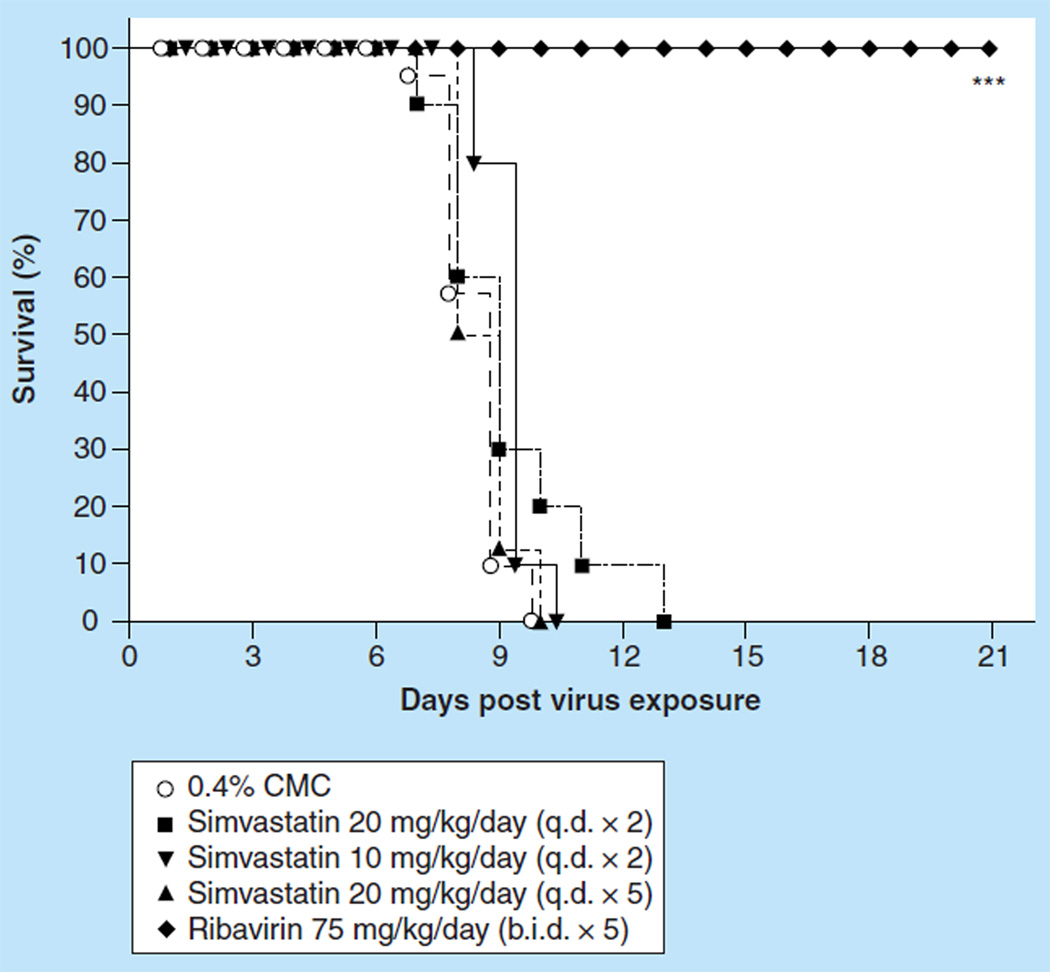

Mice infected with influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) virus were treated ip. with simvastatin in two treatment protocols: 24 h pre- and 15 min post-virus exposure, or 24 h pre- and 15 min, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h post virus exposure. Dosages used for the two treatment protocols were 20 and 10 mg/kg/day for the first schedule, and for the latter schedule 20 mg/kg/day was used. The therapy, although well-tolerated in uninfected mice (data not shown), did not significantly protect infected mice against death (Figure 2). The best effect on any parameter measured was 0.5 day prolongation in mean day to death and occasional lessening of SaO2 decline, the latter not being sustained (data not shown). Simvastatin treatment had no effects on virus lung titers or on edema-associated weight increase of infected lungs. Ribavirin, run in parallel as a positive control using 75 mg/kg/day two times a day (b.i.d.) for 5 days by the ip. treatment route, was markedly inhibitory to the infection using all disease parameters (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effect of intraperitoneally administered simvastatin treatment on the survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/NWS/33 H1N1 virus.

***p < 0.001.

b.i.d.: Two times a day; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; q.d.: Once daily.

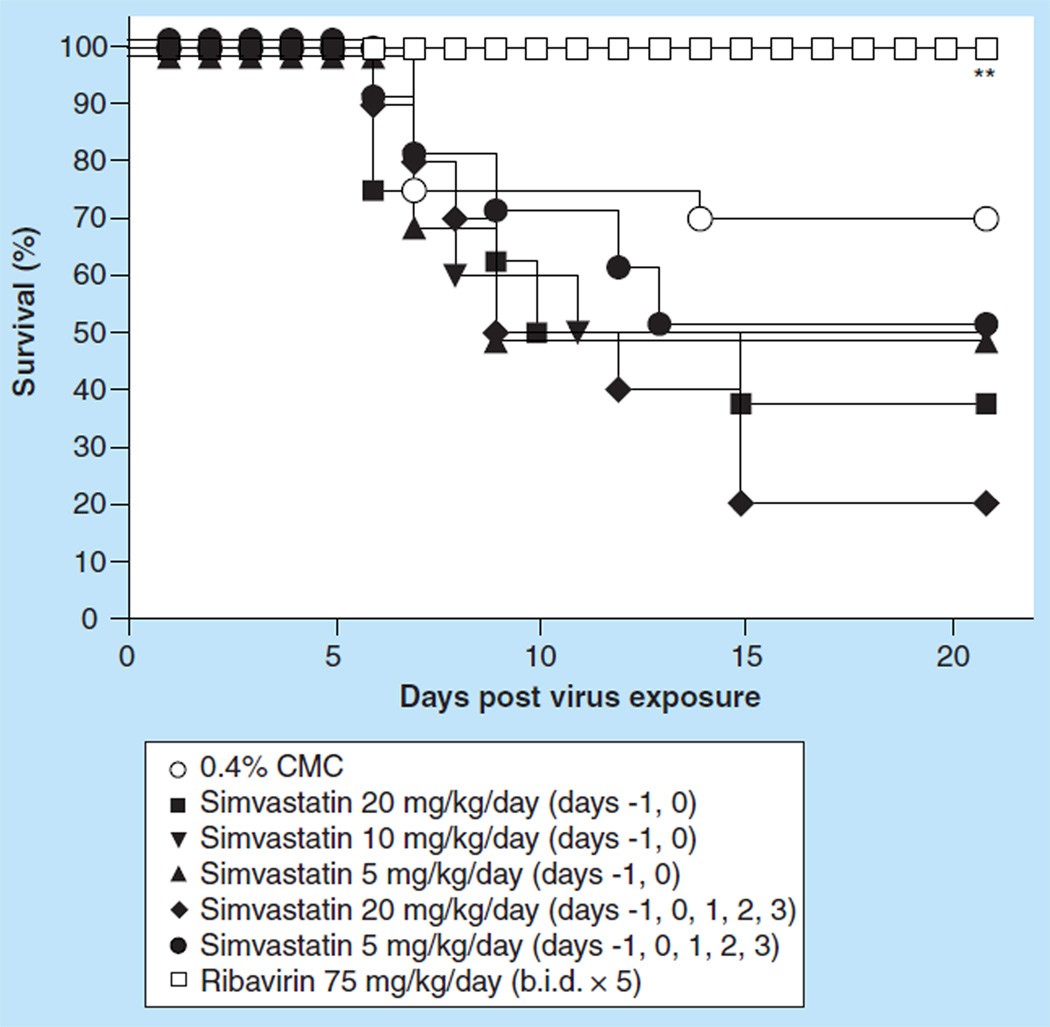

Effect of ip. treatment with simvastatin on an influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus infection in BALB/c mice

The results from the experiment using the NWS virus suggested that perhaps the infectious challenge used was too severe. In the next experiment, a less virulent inoculum of virus was used, such that only about 30% of placebo-treated mice died. Groups of ten mice were treated ip. with simvastatin at a dose of 20, 10 or 5 mg/kg/day 24 h before and 15 min after virus exposure, or at a dose of 20 or 5 mg/kg/day 24 h before, 15 min, 24 h, 48 h or 72 h post virus exposure. The viral challenge was only lethal to six of the 20 placebo-treated, infected mice (Figure 3), and the mean day-to-death, 8.2 days, was in the range expected for the placebo-treated mice. Using such a low challenge dose, it was difficult to assess antiviral effects, although ribavirin, as expected, protected 100% of infected mice from the lethal effects of the disease and significantly prevented SaO2 decline, when measured at day 11 (data not shown), and significantly reduced lung scores (p < 0.01) and lung weight increase (p < 0.01). No treatment significantly reduced day 3 and 6 virus lung titers (data not shown). However, at day 11, post virus challenge for mice treated with ribavirin, or for mice treated with placebo, virus lung titers were near the level of detection, while virus lung titers for simvastatin-treated mice were near the levels of virus lung titers at the day 6 level (data not shown). Simvastatin therapies also did not seem to ameliorate any other signs of the disease measured in the mice: a higher percentage of the infected, treated mice died in every group than were observed in the placebo-treated controls (data not shown), lung weights and scores at day 6 were equivalent to those measured in placebo-treated mice and the day 11 SaO2 values were almost uniformly lower than those in the placebo-treated controls and substantially lower than in uninfected, untreated mice (data not shown). Thus, these data gave no suggestion that simvastatin had any protective effect against an influenza A H3N2 virus infection in mice.

Figure 3.

Effect of intraperitoneal administered simvastatin treatment on the survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/Victoria/3/75 H3N2 virus.

**p = 0.005.

b.i.d.: Two times a day; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose.

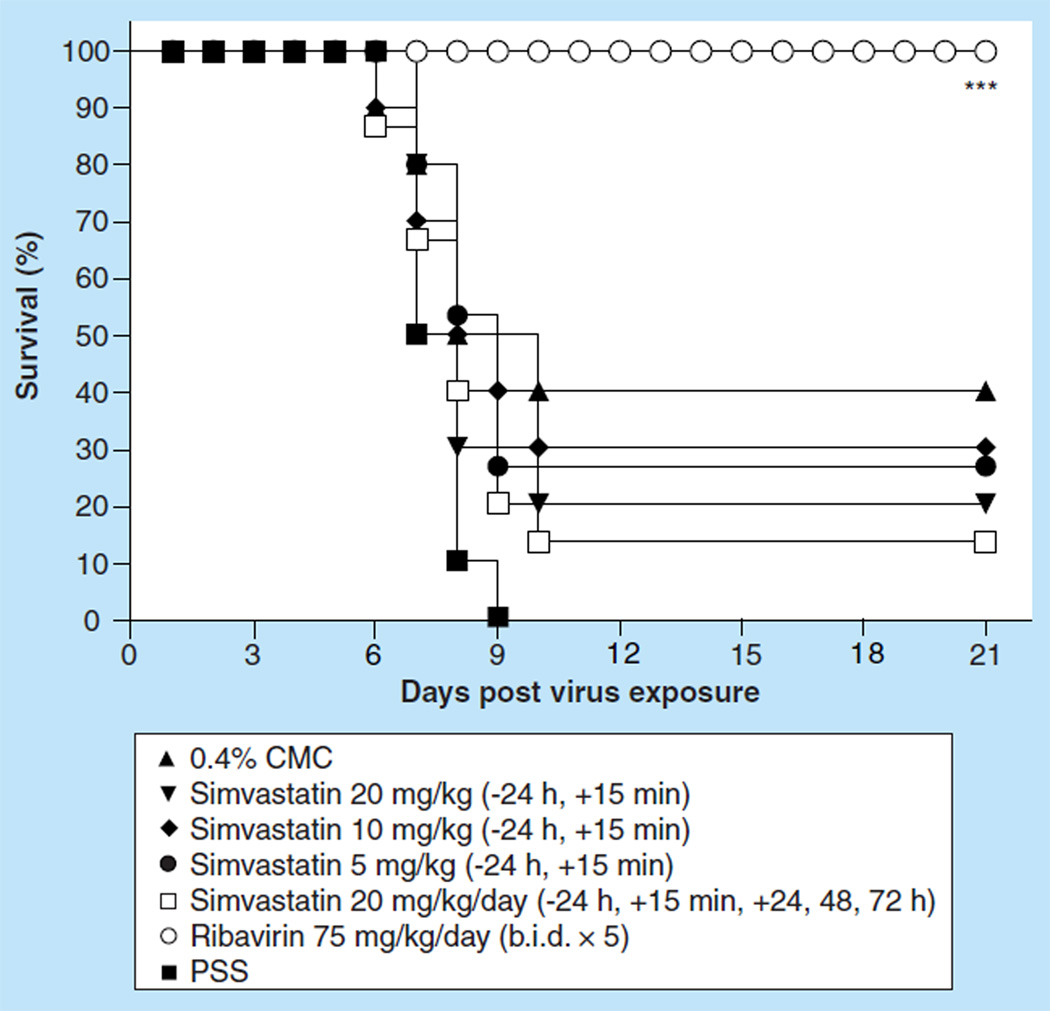

Effect of ip. treatment with simvastatin on an influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus infection in BALB/c mice

We next evaluated simvastatin efficacy in mice infected with a low pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. Initial evaluation of simvastatin was carried out by infecting groups of ten mice intranasally with a 100% lethal dose of influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 H5N1 virus infection. Because of the initial findings that no protection of mice could be obtained with simvastatin treatment, the dosing regimen was further refined to achieve better efficacy. Groups of ten mice were treated ip. with simvastatin at a dose of 20, 10 or 5 mg/kg/day 24 h before and 15 min after virus exposure, or at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day 24 h before, 15 min, 24 h, 48 h or 72 h post virus exposure. None of the simvastatin treatment regimens significantly impacted survival from the virus infection as measured by the mortality rate (Figure 4) or mean day to death, nor was loss of body weight different from placebo-treated mice (data not shown). Even more frequent therapeutic dosing did not improve survival with only 15% of mice surviving the treatment (Figure 4) and no significant extension of the mean day to death value (data not shown). In addition, the various simvastatin treatment regimens of infected mice did not significantly reduce the gross lung pathology observed for those mice at day 6 compared with the gross lung pathology observed for mice treated with placebo. Also, virus lung titers were no different than those of the placebo-treated mice, and lung weights were equivalent to the lung weights of placebo-treated mice (data not shown). By contrast, ribavirin at a dose of 75 mg/kg/day, which was also administered ip. b.i.d. for 5 days beginning 4 h before virus exposure, was very potent in treating the virus infection. Ribavirin completely protected mice from the lethal effects of the virus infection (Figure 4; p < 0.001). This protection was manifested in the prevention of SaO2 decline relative to the PSS-treated mice (p < 0.05) and the other treatments as well (data not shown). Ribavirin treatment also resulted in the significant reductions of lung scores and lung weight increases due to infection (data not shown; p < 0.05). It was interesting to note that the ribavirin treatment also significantly reduced lung virus titers at day 3 as well as at day 6 post virus challenge (data not shown; p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of intraperitoneal administered simvastatin treatment on the survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 H5N1 virus.

***p < 0.001.

b.i.d.: Two times a day; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; PSS: Physiologically sterile saline.

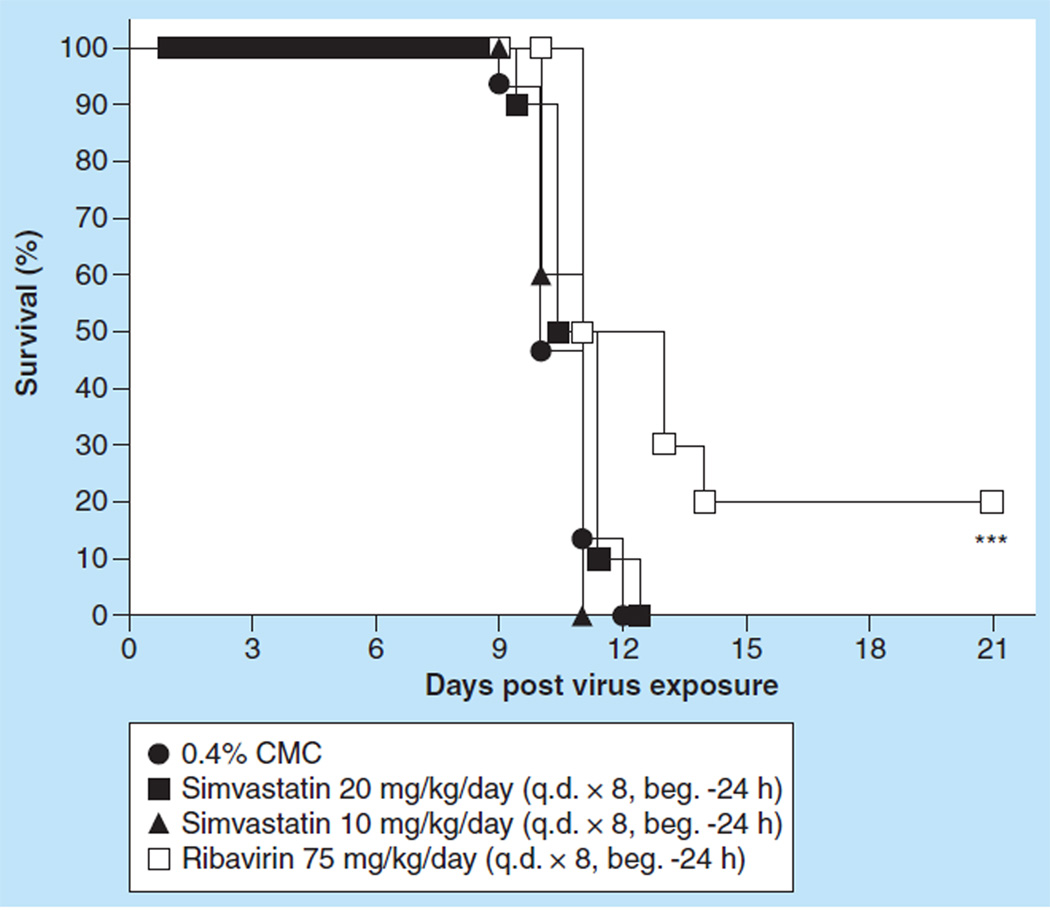

Evaluation of simvastatin on pathogenicity of influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus in mice

Evaluation of simvastatin was done in a highly pathogenic influenza A H5N1 virus infection (5 PFU inoculum) model of BALB/c mice. The mice were treated p.o. with 10 or 20 mg/kg/day of simvastatin once a day (q.d.) for 8 days beginning 24 h before virus exposure or with 75 mg/ kg/day of ribavirin by the ip. route b.i.d. for 8 days beginning 4 h before virus exposure. As controls, the infected mice were treated ip. with 0.4% CMC in parallel with simvastatin. Neither treatment of simvastatin prevented mice from death due to virus infection compared with mice treated with 0.4% CMC, whereas ribavirin did significantly delay the mortality (Figure 5; p < 0.001). None of the simvastatin treatments reduced virus lung titers; all were similar to the lung virus titers of mice treated with placebo (data not shown). However, ribavirin treatment did significantly reduce lung virus titers compared with the lung virus titers of mice treated with 0.4% CMC.

Figure 5.

Effect of intraperitoneal administered simvastatin treatment on the survival of BALB/c mice infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus.

***p < 0.001.

beg.: Beginning; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; q.d.: Once daily.

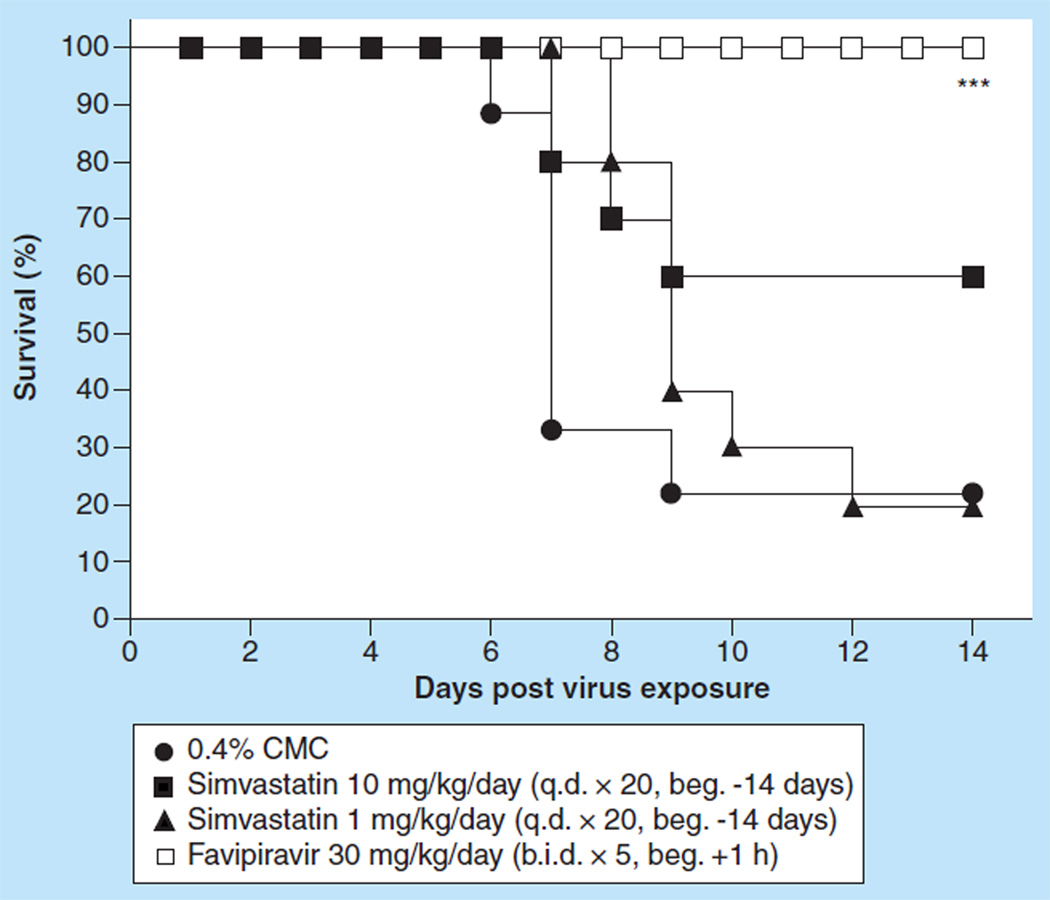

Evaluation of long-term prophylactic dosing of simvastatin on an influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus infection in BALB/c mice

Since short-term simvastatin prophylactic and therapeutic treatment regimens, or a combination of both, did not seem to demonstrate the efficacy of simvastatin for treating influenza virus infections, it was decided to pretreat mice for 14 days prior to virus challenge and then subsequently use a therapeutic treatment regimen. This might have been analogous to a human using simvastatin for its cholesterol-lowering properties and then being treated for an influenza virus infection while maintaining the use of the simvastatin medication. Mice were intranasally infected with an LD90–100 challenge dose. Groups of ten mice were pretreated with simvastatin at a dosage of 10 or 1 mg/kg/day q.d. ip. for 14 days beginning 14 days before virus exposure. Subsequently, mice were treated with simvastatin q.d. for 5 days beginning 24 h after virus exposure. Placebo (0.4% CMC) was administered ip. to ten mice at the same intervals. Other mice were also treated with favipiravir p.o., q.d., for 5 days beginning 1 hour after virus exposure. These mice constituted a positive control group.

Simvastatin administered ip. at any dose did not significantly enhance the total survivors after 14 days of infection, although 60% of the animals were alive at day 14 in the group of mice treated with 10 µg/day, q.d. (Figure 6 & Table 3). By contrast, favipiravir administered at 30 mg/ kg q.d. for 5 days protected all treated mice from death. In fact, mice would be 47-times less likely to die as rapidly when treated with favipiravir when compared with placebo-treated mice (see HRs, Table 3) while mice treated with either dose of simvastatin would be only two to four-times less likely to die as rapidly (see HRs, Table 3). However, simvastatin given at 1.0 mg/kg did significantly prolong the mean day to death of infected, treated mice compared with placebo-treated mice (9.3 days compared with 7.1 days, p < 0.01, Table 3). Simvastatin did not significantly reduce virus lung titers at day 3 or at day 6 (data not shown). Lung scores were only significantly reduced at day 3 when mice were treated with 10 mg of simvastatin (p < 0.05; data not shown). However, favipiravir significantly reduced lung scores at days 3 and 6 post virus exposure as well as lung virus titers at day 3 (p < 0.05–p < 0.001; data not shown). Histopathological examination of lungs from each treatment group at days 3 and 6 revealed extremely mild-to-moderate pathology in all groups. At day 3, the pathology was extremely mild and characterized by scattered bronchioles containing dense luminal aggregates of necrotic cellular debris and individual lining cells that were degenerate or necrotic. At day 6, rims of lymphocytes and neutrophils surrounding scattered small vessels and bronchioles characterized the pathology. The bronchioles contained variable amounts of necrotic cellular debris and neutrophils. In some bronchioles, lining cells were swollen and rare individual necrotic lining cells were present. Multifocal groups of airspaces were filled with sheets of neutrophils. This damage was considered moderate. Thus, for the most part, simvastatin, when administered using a prolonged prophylaxis dosing regimen combined with a therapeutic treatment regimen, was no more efficacious than when using simvastatin just therapeutically. There was only a modicum of amelioration of disease.

Figure 6.

Effect of prolonged prophylaxis with simvastatin on survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 H5N1 virus.

***p < 0.001.

beg.: Beginning; b.i.d.: Two times a day; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; q.d.: Once daily.

Table 3.

Effect of prolonged prophylaxis with simvastatin on various death parameters calculated in BALB/c mice infected with influenza/A/Duck/MN/1525/81 H5N1 virus.

| Treatment | Live/total mice | Mean days to death† ± SD |

Median day of death‡ |

Hazard ratio (95% CI)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.4% CMC (q.d. × 20, beg. -14 day) | 2/9 | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 7.0 | – |

| Simvastatin 10 mg/kg/day (q.d. × 20, beg. -14 day) | 6/10 | 7.8 ± 1.0 | Undefined | 3.8 (0.9–15.4) |

| Simvastatin 1.0 mg/kg/day (q.d. × 20, beg. -14 day) | 2/10 | 9.3 ± 1.3** | 9.0 | 2.1 (0.6–71) |

| T-705 30 mg/kg/day (q.d. × 5, beg. +1 h) | 10/10* | >14.0 ± 0.0** | Undefined | 47.7 (8.4–272) |

Mean days to death of mice dying prior to day 14 after virus exposure.

The time at which fractional survival equals 50% (i.e., the calculated time at which half the subjects have died and half are still alive).

Hazard ratio is calculated relative to the placebo.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01 compared with CMC-treated controls.

beg.: Beginning; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; q.d.: Once daily; SD: Standard deviation.

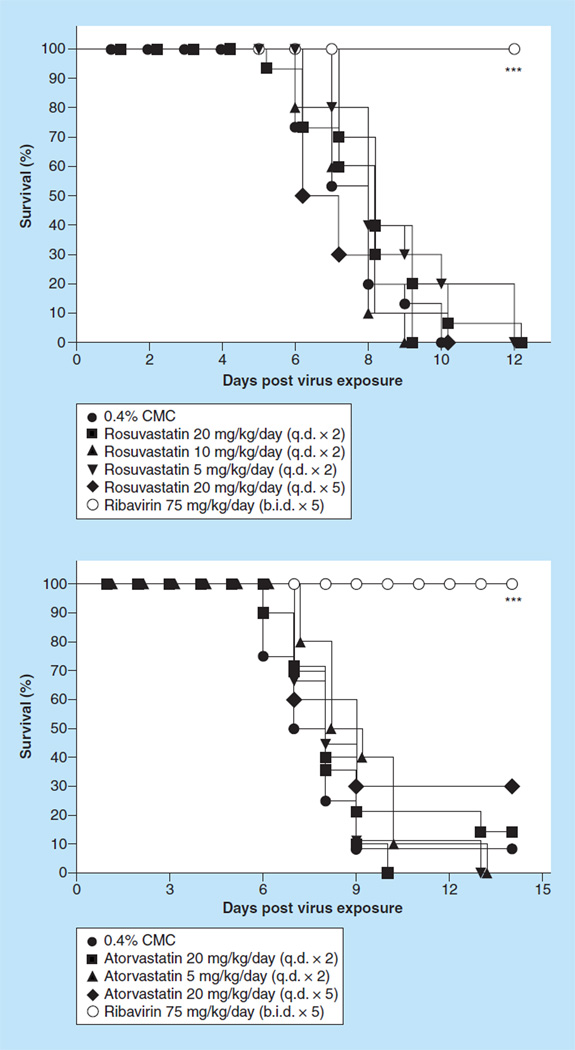

Evaluation of various statins on a pandemic influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection in BALB/c mice

Since simvastatin prophylactic and therapy dosing regimens seemed not to greatly impact the outcome of lethal disease nor significantly impact a modestly lethal infection in the virus models used, the question of whether other clinically relevant statins might be more efficacious in treating influenza infections was answered. Evaluation of other clinically used statins was performed in an influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus mouse model using a 100% lethal dose.

A more potent cholesterol-lowering statin, rosuvastatin (Crestor®, AstraZeneca) was tested for efficacy as an unformulated drug by the p.o. route used for human dosing. Groups of 20 mice were administered rosuvastatinin 0.4% CMC by the p.o. route at doses of 20, 10, 5 mg/kg/day q.d. for two days beginning 24 h prior to virus exposure. In addition, one group was treated with rosuvastatinin 0.4% CMC at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day for 5 days beginning 24 h prior to virus exposure. 20 mice were given ribavirin ip. at 75 mg/kg/day b.i.d. for 5 days beginning on day 0, the day of virus exposure to mice. Doses were given 8 h apart, beginning immediately after virus infection. In addition, 30 mice each received 0.4% CMC p.o. using the 2-day treatment regimen described above for rosuvastatin. Another 30 mice each received PSS ip. b.i.d. for 5 days beginning on day 0, the day of virus exposure to mice.

Rosuvastatin at any dose was well tolerated by uninfected mice; no significant weight losses were recorded (data not shown). Rosuvastatin did not protect mice against death, regardless of the treatment regimen used (Figure 7A). However, the positive control drug, ribavirin, did protect all treated mice from death. When measuring other parameters related to death, rosuvastatin treatment of mice did not significantly extend the mean day of death for those treatment groups nor did rosuvastatin treatment of mice increase the number of survivors (data not shown). In fact, the rapidity with which mice would die from treatment with rosuvastatin (HRs, data not shown) was the same as for mice not treated with any drug, whereas mice treated with ribavirin would take at least 16-times longer to die from the infection, if at all, compared with untreated mice. Rosuvastatin also did not protect mice from losing large amounts of weight during the disease process; these weight losses were comparable to the weight losses of mice not treated with any drug (data not shown). When assessing the various parameters associated with lung disease associated with viral infection (data not shown), it was apparent that rosuvastatin did not ameliorate lung disease in treated mice when compared with mice receiving no treatment. For example, the lung scores and lung weights at days 1, 3 and 4 were nearly the same for rosuvastatin-treated mice as they were for untreated mice. By contrast, mice treated with ribavirin had significantly lower lung scores at days 3 and 6 post-virus exposure (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). An exception to this total lack of positive impact on lung disease was the singular finding that treatment of mice with rosuvastatin at 20 mg/ kg/day on day 3 post virus exposure did significantly reduce virus lung titers (log10, 4.8 ± 0.4/g tissue) compared with the lung titers from mice treated with 0.4% CMC (log10, 5.7 ± 0.3/g tissue, p < 0.05). However, that did not translate into better lung function as measured by arterial oxygen saturation. The percent mean arterial saturation in mice treated with certain doses of rosuvastatin at day 6 and day 8 was significantly worse (lower) at days 6 and 8 compared with mice receiving PSS and/or 0.4% CMC (data not shown, p < 0.01–p < 0.001). Thus, rosuvastatin did not significantly protect mice from death due to an infection with pandemic H1N1 influenza A/CA/04/09 virus infection in a BALB/c mouse model influenza, nor did it, for the most part, ameliorate any of the lung disease caused by the virus infection as measured by mean arterial oxygen saturation, lung pathology, virus lung score and weights and virus lung titers.

Figure 7.

Effect of intraperitoneal administered rosuvastatin and atorvastatin on survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus.

***p < 0.001 versus 0.4% CMC and PSS.

b.i.d.: Two times a day; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; PSS: Physiologically sterile saline; q.d.: Once daily.

Another commonly prescribed statin is atorvastatin (Lipitor®). Another experiment was therefore carried out using the more potent and unformulated version of atorvastatin and using the same dosing regimen as described above for rosuvastatin. Atorvastatin, as with other statins tested, was well tolerated at any dose in uninfected mice (data not shown). However, atorvastatin did not significantly protect mice against death regardless of the treatment regimen used (Figure 7B), although at the 20/mg/day dose three out of ten mice survived to day 21. As expected, the positive control drug, ribavirin, did protect all treated mice from death. When measuring other parameters related to death, atorvastatin treatment of mice did not significantly extend the mean day of death nor did atorvastatin treatment of mice significantly increase the number of survivors (data not shown). In fact, the rapidity with which mice would die from treatment with atorvastatin (HRs, data not shown) was nearly the same as for mice not treated with any drug, whereas mice treated with ribavirin would take at least 43-times longer to die from the infection, if at all, compared with untreated mice. Atorvastatin also did not protect mice from losing large amounts of weight during the disease process; these weight losses were comparable to the weight losses of mice not treated with any drug (data not shown). An exception to this observation was the three mice treated with 20 mg/kg/day (q.d. × 5) atorvastatin; these mice gained back substantial amounts of weight by day 21. When assessing the various parameters that are an indication of lung disease associated with viral infection (data not shown), it was apparent that atorvastatin did not ameliorate lung disease in treated mice when compared with mice receiving no treatment. For example, the lung scores and lung weights at day 6 were nearly the same or worse for atorvastatin-treated mice than they were for untreated mice. By contrast, mice treated with ribavirin had significantly lower lung scores (p < 0.05) and lung weights (p < 0.05–p < 0.001) at day 6 post-virus exposure. The descriptions of lung pathology for lungs from atorvastatin-treated mice resembled those for lungs from untreated mice at days 3 and 6 after virus exposure. The pathology was usually described as a few bronchioles containing necrotic cellular debris and having necrotic lining epithelial cells. In addition, there was usually mild perivascular edema associated with moderate infiltration of lymphocytes and sometimes neutrophils. Atorvastatin also did not significantly reduce virus lung titers compared with the lung titers from mice treated with 0.4% CMC (data not shown), although ribavirin treatment resulted in significant reductions of virus lung titers at day 6 (p < 0.001 vs CMC). In addition, atorvastatin treatment of mice did not result in any beneficial effect on lung function as measured by SaO2 (data not shown).

As with rosuvastatin, atorvastatin did not significantly protect mice from death due to an infection with pandemic H1N1 influenza A/CA/04/09 virus infection in a BALB/c mouse model of influenza, nor did it ameliorate any of the lung disease caused by the virus infection as measured by mean SaO2, lung pathology, virus lung score and weights and virus lung titers.

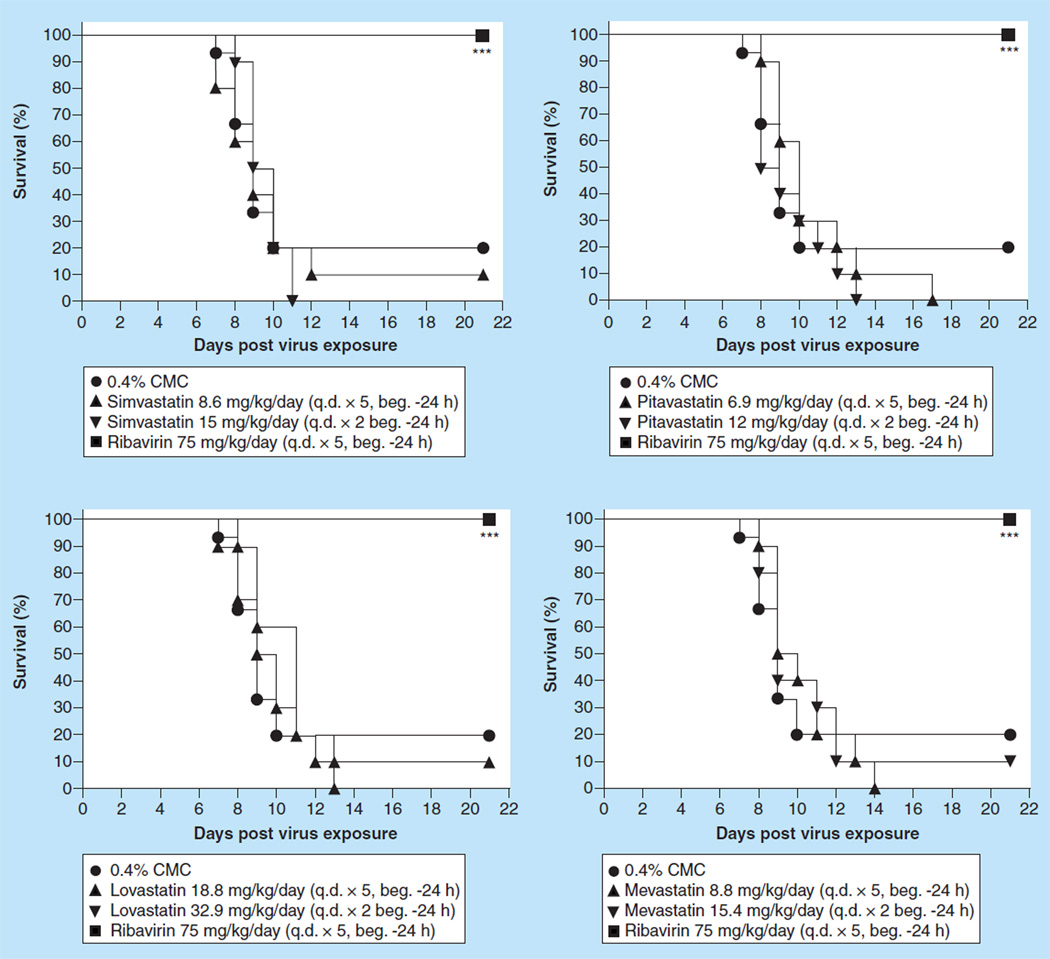

To see if the route of administration influenced protection against death by statins, a number of statins were given to mice by the oral route, the normal route of administering statins to humans, and using human equivalent doses of each statin. Thus, the statins were evaluated for efficacy in an influenza A H1N1pdm09 BALB/c model using a p.o. route of administration. Ten mice were treated with 8.6 mg/kg/day of simvastatin q.d. for 5 days or with 15 mg/kg/day of simvastatin q.d. for 2 days beginning 24 h before virus exposure. Ten mice were treated with 6.9 mg/kg/day of pitavastatin q.d. for 5 days or with 12 mg/kg/ day of pitavastatin q.d. for 2 days beginning 24 h before virus exposure. Ten mice were treated with 18.8 mg/kg/day of lovastatin q.d. for 5 days or with 32.9 mg/kg/day of lovastatin q.d. for 2 days beginning 24 h before virus exposure and ten mice were treated with 8.8 mg/kg/day of mevastatin q.d. for 5 days or with 15.4 mg/kg/day of mevastatin q.d. for 2 days beginning 24 h before virus exposure. Ribavirin was given ip. at a dose of 75 mg/kg/day b.i.d. for 5 days beginning 4 h before virus exposure. As controls, the infected mice were treated p.o. with 0.4% CMC in parallel with the various statins. Pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus-infected mice receiving the various statins by the p.o. route were not protected against death, regardless of the dose and the frequency of administration compared with infected mice receiving 0.4% CMC (Figure 8). Weight loss due to the statin treatments was not ameliorated compared with the weight loss measured for placebo-treated mice (data not shown). In addition, lung weights, lung score and lung virus titers for each group of statin-treated mice were similar to the values of those parameters measured in placebo-treated mice (data not shown). An exception to this generalization were mice treated with lovastatin at 18.8 mg/kg/day; these mice had significantly lower virus lung titers (p < 0.05) and slightly, but significantly, lower lung scores (p < 0.05). In addition, mice treated with mevastatin at 15.4 mg/g (q.d. × 2) did not appear to have gross pathology (p < 0.05) and mice treated with mevastatin at 8.8 mg/kg/day (q.d. × 5) had lower virus lung titers (p < 0.05). Mice treated with simvastatin at 15 mg/kg/day q.d. for two days had significantly lower lung weights (p < 0.05). On the other hand, all mice treated with ribavirin survived the virus infection (p < 0.001) had significantly lower lung scores (p < 0.05–p < 0.01) and had much less virus replicating in the lungs (p < 0.001). Overall, the treatment with statins by the oral route was not effective in protecting mice against death nor was there a single dosing regimen of any statin that ameliorated all of the deleterious effects on the lung caused by the virus infection that ribavirin treatment accomplished. Oral administration of statins also appeared to be no more effective than delivering the statins by the ip. route.

Figure 8.

Effect of orally administered statins on survival of BALB/c mice infected with influenza A/CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus.

***p < 0.001 versus 0.4% CMC.

beg.: Beginning; CMC: Carboxymethyl cellulose; q.d.: Once daily.

Discussion

It has been suggested that the hyperinflammatory response induced in the lungs of infected people, as well as the systemic cytokine-mediated immune inflammatory reactions, should be the targets of chemotherapeutic approaches for treating influenza infections to prevent the morbidity and mortality associated with severe influenza infections. Among the agents recommended for evaluation have been the statins, which have been approved for other indications such as lowering cholesterol levels [6,23,50,51]. Such recommendations have been based on retrospective interpretation of several epidemiological studies on the efficacy of statins as cholesterol-lowering agents. For example, statin usage seemed to be linked to protection against death in patients with chronic pulmonary obstructive disease [52]. In another study, a Dutch database of 60,000 primary care patients was studied for evidence of statin use being associated with reduced pneumonia during the ‘flu season’; some association with reduced pneumonia and statin use was noted [53]. Another pharmacoepidemiological study showed similar trends [51]. Presumably, the putative mechanism of action would be to inhibit the production of proinflammatory factors that would induce the hyperinflammatory response in the lungs and the serum cytokine storm observed in some patients with life-threatening influenza infections [54]. A question not addressed by these studies is whether a reduction of the inflammatory response or cytokine storm is sufficient to prevent death or to promote timely recovery, or is control/removal of the virus inducing these responses also necessary. Therefore, it was of interest to initially determine if any statin would significantly ameliorate the consequences of acute, lethal influenza virus infection in mice.

Among the statins (Figure 1), simvastatin has been the most studied for its effects in vivo against virus infections. In previous studies, simvastatin has been shown to have antiviral activities against HIV-1 [55], poliovirus [56] and respiratory syncytial virus [57]. In addition, the administration of simvastatin to severe combined immunodeficiency mice followed by inoculation with EBVtransformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and resulted in delayed development of EBV lymphomas and, thus, prolonged survival of animals. Therefore, simvastatin was proposed for the treatment or prevention of EBV-associated lymphoma [58]. Bader and Korba demonstrated that simvastatin exhibited a strong anti-viral activity against HBV in vitro [59]. Mihaila et al. reported that simvastatin showed a significant reduction in the level of viremia for the treatment of patients infected with HCV, who had hepatic cytolysis [60].

In the current studies, the BALB/c mice, which were infected with an influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus, an influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus, an influenza A/NWS/33 (H1N1) virus, an influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus or an H1N1pdm09 virus and were administered ip. or p.o. with simvastatin before or after virus exposure, still experienced mortality and weight loss equivalent to placebo controls. Thus, simvastatin was not effective in treating the influenza virus infections in BALB/c mice. Any profound efficacy was only demonstrated in animals that were treated with ribavirin or favipiravir. Ribavirin, run in parallel as a positive control using 75 mg/ kg/day b.i.d. for 5 days by the ip. treatment route, was markedly inhibitory to the infection regardless of the disease parameter measured. Because the mechanism of statins is to prevent acute lung injury, exacerbated by a hyperinflammatory response, and not to directly inhibit virus replication, the lack of effects on virus replication are to be expected. However, the lack of effect on lung scores and lung pathogenesis, as observed by histopathology, suggests that the anti-inflammatory properties of simvastatin are not sufficient to protect mice against death by influenza viruses. However, for some of the studies presented in this paper, on occasional statin treatment appeared to increase the time to death and thus suggested a possible amelioration of disease, but these findings were not statistically significant. These findings contrast with other studies in which statins or cholesterol-lowering drugs were found to be efficacious alone [41] or in combination with other products such as caffeine [61]. In the latter study, the models used were not very lethal (appears to 20% mortality) and the apparent amelioration of lung pathology was modest. It was difficult to tell if all the proper controls were used because, for example, neither agent was tested alone and it appeared that there were no controls used for the intragastric administration route. In another study, a nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drug, gemfibrozil, was shown to modestly improve survival in an H2N2 influenza A virus BALB/c mouse model; survival against H2N2 in mice increased from 26 to 52% after an ip. injection of gemfibrozil 4–10 days after inoculation with the virus [42]. By contrast, rosuvastatin was not found to alter influenza A mortality or enhance its clearance from the lung in vivo in a C57Bl/6 model using influenza A/ Udorn/72 (H3N2) or influenza A/WSN/33 (H1N1) viruses [62].These findings are important because some have suggested that the C57BL/6J mouse strains are more appropriate for the evaluation and identification of intrinsic pathogenicity markers of 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza viruses than the BALB/c mouse, because the latter strain of mouse mounts a predominantly Th2 immunological response with more inflammation while the C57Bl/6 mouse mounts a Th1 immunological response skewed to Th1 and less inflammation [63]. In addition, the DBA2J mouse may also be an appropriate virus pathology model for severe influenza disease because these mice replicate more of the virus in their lungs, express much greater levels of cytokines and chemokines and demonstrate a much more pronounced lung pathology compared with infected C57BL/6 mice [64]. These mice also have a much stronger inflammatory immune response early in the infection leading to severe immune pathology as has been postulated for severe human disease [65]. Finally, there is often no need to adapt clinical isolates of influenza viruses to cause infection in these mice as was shown with influenza AH1N1pdm09 isolates [64]. Thus, such viruses maintain the same genetic background that they had when infecting humans. The study described above and the results from the current study suggest that the mouse strain makes no difference; either statins are not very effective in treating the influenza virus in mice or the hypothesis that statins can be used to treat influenza virus infections is not valid. Alternatively, the treatment regimen may have been too short, allowing proinflammatory cytokine levels to rebound or the treatment regimens used in the current study may not have been appropriate for the models used. In addition, the disease associated with each virus mouse model may have been too severe to be successfully treated (i.e., LD100 causes too severe disease) with these agents, or the currently circulating H1N1pdm09 viruses were refractory to treatment with such agents.

Finally, one could argue that it is not clear that any of the influenza viruses used in the presented study caused death through increased inflammation or because of virus replication. If death was caused principally by high virus replication and subsequent destruction of lung tissue by the virus and the induced cytotoxic T lymphocytes responses, statins would not be expected to have an effect. This argument would be much more valid if both processes were separate and independent of one another. It is likely that viral replication induces a detrimental upregulation of innate immune response as well as causing tissue necrosis due to viral cytopathic effects leading to severe impairment of tissue function (i.e., lung pathogenesis). For example, using the same influenza CA/04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus used in the current study, Zarogiannis et al. demonstrated that the virus induced a robust hyperinflammatory response in the lungs including high levels of IL-6, which contributed to the lethality of influenza disease in mice [66]. Itoh et al. also demonstrated a similar phenomenon with the same virus strain [67]. In addition, it has been shown that an sphingosine analog (AAL-R), an inflammatory agent, provided significant protection against mortality due to an infection when compared with oseltamivir, a direct inhibitor of virus replication drug [68]. In this case, AAL-R controlled the cellular and proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine responses to limit immunopathological damage to protect mice from death owing to the consequences of virus infection. In addition, AAL-R administration has also has been shown to perturb the innate and adaptive immune responses in mice infected with mouse-adapted A/WSN/33 H1N1 (another virus used in the current study) influenza virus to limit immunemediated tissue damage [69,70]. One study also suggests that various strains of mouse-adapted influenza viruses cause lethality in mice, in part due to a dysregulated immune response to the virus. For example, prophylactic treatment with a stabilized chemical analog of dsRNA (PIKA), a broad spectrum innate immune response promoter, protected mice infected with replication of three mouse-adapted laboratory strains (H1N1 and H3N1) of influenza [71]. Similar results with the same compound against three clinical isolates from humans, an H5N1 virus, an H9N2 virus and a swine-origin H1N1 virus from the 2009 pandemic [72]. Highly pathogenic strains of avian influenza H5N1 virus have long been recognized to cause severe disease because by perturbing the host inflammatory immune response. It has been demonstrated that BALB/c mice infected with highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 strains induced an innate immune response that caused the mice to go into shock and resulted in multiple organ failure [73]. In addition, in that same study, the levels of some cytokines (IFN-g, IL-6 and IL-10) were greatly elevated in mice that were terminated because of severe weight loss. It has also been shown that the hemagglutinin protein of influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) contributes to the hyperinduction of proinflammatory cytokines in human epithelial cells [74]. These supportive findings suggest that the mouse models used in the current study could have easily modeled not only the contribution of the virus to necrosis, but the contribution of the dysregulated immune response to the pathogensis and death of infected mice, especially when the same or very similar viruses and strains of mice were used that were used in previous studies cited. Thus, it is likely that the statins do not ameliorate the effects of mortality caused by influenza infections of BALB/c mice.

Future perspective.

It is likely that in the future a number of US FDA-approved drugs will be repurposed from their original indication and licensed for use as antiviral drugs. There are now many studies being conducted that focus on repurposing drugs for treatment of a variety of viral diseases. For example, such compounds as the statins, gemfibrozil and beraprost have been reported to have efficacy for treating influenza virus infections in mice and the first two have been reported anecdotally to be efficacious in humans. Such compounds, if further studies in different influenza animal models show some sort of efficacy for these drugs used either alone or in combination, could be approved for treating influenza virus infections in the not too distant future.

Executive summary.

Evaluation of simvastatin on death & weight change of BALB/c mice infected with a lethal dose of influenza A/NWS/33 H1N1 virus

-

▪

Simvastatin is not active against influenza A/NWS/33 H1N1 virus.

Effect of intraperitoneal treatment with simvastatin on an influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus infection in BALB/c mice

-

▪

Simvastatin is not active against influenza A/Victoria/3/75 (H3N2) virus.

Effect of intraperitoneal treatment with simvastatin on an influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus infection in BALB/c mice

-

▪

Simvastatin is not active against low pathogenic avian influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1).

Evaluation of simvastatin on pathogenicity of influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus in mice

-

▪

Simvastatin is not active against highly pathogenic avian influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 virus.

Evaluation of various statins on a pandemic influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection in BALB/c mice

-

▪

Simvastatin is not active against influenza A/CA04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus.

Evaluation of long-term prophylactic dosing of simvastatin on an influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1) virus infection in BALB/c mice

-

▪

Long-term prophylaxis with simvastatin is not active against low pathogenic avian influenza A/Duck/MN/1525/81 (H5N1).

CA04/09 H1N1pdm09 virus

-

▪

Evaluation of various statins on a pandemic influenza A H1N1pdm09 virus infection in BALB/c mice.

-

▪

The data suggest that statins, using the doses and treatment regimens outlined for the current studies, were not effective in ameliorating any parameter of disease that was measured in the mouse models used. Thus, the concept of repurposing statins to treat influenza infections is either not valid, or the concept cannot be measured in the mouse models used and should be tested in a different animal model.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NIH/NIAID Contract NO1-AI-15435.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

▪ of interest

▪▪ of considerable interest

- 1.Cheng KF, Leung PC. What happened in China during the 1918 influenza pandemic? Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;11(4):360–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaye D, Pringle CR. Avian influenza viruses and their implication for human health. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;40(1):108–112. doi: 10.1086/427236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller-Meeks M. Flu season and the threat of a pandemic. Iowa Med. 2006;96(6):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parry J. Conference urges greater effort to reduce human threat from avian influenza. BMJ. 2007;334(7594):607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39161.772581.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beigel JH, Farrar J, Han AM, et al. Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;353(13):1374–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitley RJ, Monto AS. Seasonal and pandemic influenza preparedness: a global threat. J. Infect. Dis. 2006;194(Suppl. 2):S65–S69. doi: 10.1086/507562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Henrickson KJ. Update on influenza diagnostics: lessons from the novel H1N1 influenza A pandemic. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012;25(2):344–361. doi: 10.1128/CMR.05016-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fedson DS. Pandemic influenza: a potential role for statins in treatment and prophylaxis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006;43(2):199–205. doi: 10.1086/505116. ▪▪ Describes the hypothesis that statins could be used as potential drugs for treating influenza infections.

- 9.Thomas JK, Noppenberger J. Avian influenza: a review. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2007;64(2):149–165. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trampuz A, Prabhu RM, Smith TF, Baddour LM. Avian influenza: a new pandemic threat? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2004;79(4):523–530. doi: 10.4065/79.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leneva IA, Goloubeva O, Fenton RJ, Tisdale M, Webster RG. Efficacy of zanamivir against avian influenza A viruses that possess genes encoding H5N1 internal proteins and are pathogenic in mammals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):1216–1224. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1216-1224.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yen HL, Monto AS, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Virulence may determine the necessary duration and dosage of oseltamivir treatment for highly pathogenic A/ Vietnam/1203/04 influenza virus in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2005;192(4):665–672. doi: 10.1086/432008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govorkova EA, Webster RG. Combination chemotherapy for influenza. Viruses. 2010;2(8):1510–1529. doi: 10.3390/v2081510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bearman GM, Shankaran S, Elam K. Treatment of severe cases of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza: review of antivirals and adjuvant therapy. Recent Pat. Antiinfect. Drug Discov. 2010;5(2):152–156. doi: 10.2174/157489110791233513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baranovich T, Webster RG, Govorkova EA. Fitness of neuraminidase inhibitor-resistant influenza A viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011;1(6):574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurt AC, Chotpitayasunondh T, Cox NJ, et al. Antiviral resistance during the 2009 influenza A H1N1 pandemic: public health, laboratory, and clinical perspectives. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012;12(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singer AC, Nunn MA, Gould EA, Johnson AC. Potential risks associated with the proposed widespread use of Tamiflu. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115(1):102–106. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tisoncik JR, Korth MJ, Simmons CP, Farrar J, Martin TR, Katze MG. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76(1):16–32. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clark NM, Lynch JP., 3rd Influenza: epidemiology, clinical features, therapy, and prevention. Semin Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011;32(4):373–392. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1283278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Risk of pneumonia in patients taking statins: population-based nested case-control study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2011;61(592):e742–e748. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X606654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothberg MB, Bigelow C, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK. Association between statins given in hospital and mortality in pneumonia patients .J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27(3):280–286. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1826-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An SC, Xu LL, Li FD, Bao LL, Qin C, Gao ZC. Triple combinations of neuraminidase inhibitors, statins and fibrates benefit the survival of patients with lethal avian influenza pandemic. Med. Hypotheses. 2011;77(6):1054–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlienger RG, Fedson DS, Jick SS, Jick H, Meier CR. Statins and the risk of pneumonia: a population-based, nested case–control study. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(3):325–332. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Budd A, Alleva L, Alsharifi M, et al. Increased survival after gemfibrozil treatment of severe mouse influenza. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51(8):2965–2968. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00219-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng BJ, Chan KW, Lin YP, et al. Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105(23):8091–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711942105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aldridge JR, Jr, Moseley CE, Boltz DA, et al. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells are the necessary evil of lethal influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(13):5306–5311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900655106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moseley CE, Webster RG, Aldridge JR. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor and AMP-activated protein kinase agonists protect against lethal influenza virus challenge in mice. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses. 2010;4(5):307–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo PC, Tung ET, Chan KH, Lau CC, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Cytokine profiles induced by the novel swine-origin influenza A/H1N1 virus: implications for treatment strategies. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201(3):346–353. doi: 10.1086/649785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hui DS, Lee N, Chan PK. Clinical management of pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection. Chest. 2010;137(4):916–925. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alleva LM, Cai C, Clark IA. Using complementary and alternative medicines to target the host response during severe influenza. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2010;7(4):501–510. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butler D. Cheaper approaches to flu divide researchers. Nature. 2007;448(7157):976–977. doi: 10.1038/448976b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fedson DS. Confronting an influenza pandemic with inexpensive generic agents: can it be done? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2008;8(9):571–576. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70070-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bereswill S, Muñoz M, Fischer A, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol, curcumin and simvastatin in acute small intestinal inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5(12):E15099. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enserink M. Infectious disease: old drugs losing effectiveness against flu; could statins fill gap? Science. 2005;309(5743):1976–1977. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5743.1976a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fedson DS. Confronting the next influenza pandemic with anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory agents: why they are needed and how they might work. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses. 2009;3(4):129–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00090.x. ▪▪ Describes the hypothesis that statins could be used as potential drugs for treating influenza infections.

- 36. Vandermeer ML, Thomas AR, Kamimoto L, et al. Association between use of statins and mortality among patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza virus infections: a multistate study. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205(1):13–19. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir695. ▪▪ A key retrospective human clinical study that is the basis for the hypothesis that statins could be used as potential drugs for treating influenza infections.

- 37. Walsh EE. Statins and influenza: can we move forward? J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205(1):1–3. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir693. ▪▪ A review that offers counter arguments to the hypothesis that statins could be used as potential drugs for treating influenza infections.

- 38.Jacobson JR, Dudek SM, Birukov KG, et al. Cytoskeletal activation and altered gene expression in endothelial barrier regulation by simvastatin. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2004;30(5):662–670. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0267OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jacobson JR, Barnard JW, Grigoryev DN, Ma SF, Tuder RM, Garcia JG. Simvastatin attenuates vascular leak and inflammation in murine inflammatory lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. 2005;288(6):L1026–L1032. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00354.2004. ▪ Shows that simvastatin induced a pronounced endothelial barrier protection in a murine model of acute lung injury as a way of ameliorating lung pathogenesis.

- 40.Terblanche M, Smith TS, Adhikari NK. Statins, bugs and prophylaxis: intriguing possibilities. Crit. Care. 2006;10(5):168. doi: 10.1186/cc5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Haidari M, Ali M, Casscells SW, Madjid M. Statins block influenza infection by down-regulating rho/rho kinase pathway. Circulation. 2007;116 Abstract 147. ▪ Outlines a potential mechanism of action whereby statins could inhibit influenza virus infections.

- 42.Furuta Y, Takahashi K, Fukuda Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of antiinfluenza virus compound T-705. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46(4):977–981. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.977-981.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi K, Furuta Y, Fukuda Y, et al. In vitro and in vivo activities of T-705 and oseltamivir against influenza virus. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2003;14(5):235–241. doi: 10.1177/095632020301400502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sidwell RW, Barnard DL, Day CW, et al. Efficacy of orally administered T-705 on lethal avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51(3):845–851. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01051-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smee DF, Hurst BL, Wong MH, et al. Effects of the combination of favipiravir (T-705) and oseltamivir on influenza A virus infections in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54(1):126–133. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00933-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sidwell RW, Bailey KW, Wong MH, Huffman JH. In vitro and in vivo sensitivity of a non-mouse-adapted influenza A (Beijing) virus infection to amantadine and ribavirin. Chemotherapy. 1995;41(6):455–461. doi: 10.1159/000239382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sidwell RW, Smee DF, Huffman JH, et al. In vivo influenza virus-inhibitory effects of the cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitor RJW-270201. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45(3):749–757. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.3.749-757.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reed LJ, Muench N. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sidwell RW, Huffman JH, Gilbert J, et al. Utilization of pulse oximetry for the study of the inhibitory effects of antiviral agents on influenza virus in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1992;36(2):473–476. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.2.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enserink M. Infectious disease. Old drugs losing effectiveness against flu; could statins fill gap? Science. 2005;309(5743):1976–1977. doi: 10.1126/science.309.5743.1976a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rainsford KD. Influenza (“Bird Flu”) inflammation and anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs. Inflammopharmacology. 2006;14(1–2):2–9. doi: 10.1007/s10787-006-0002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frost FJ, Petersen H, Tollestrup K, Skipper B. Influenza and COPD mortality protection as pleiotropic, dose-dependent effects of statins. Chest. 2007;131(4):1006–1012. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hak E, Hoes AW. Statins and outcomes in patients with pneumonia: appreciating bias and precision in study. BMJ. 2006;333(7578):1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39038.515521.1F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forrester JS, Libby P. The inflammation hypothesis and its potential relevance to statin therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007;99(5):732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amet T, Nonaka M, Dewan MZ, et al. Statin-induced inhibition of HIV-1 release from latently infected U1 cells reveals a critical role for protein prenylation in HIV-1 replication. Microbes Infect. 2008;10(5):471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu S, Rodriguez AV, Tosteson MT. Role of simvastatin and methyl-beta-cyclodextrin [corrected] on inhibition of poliovirus infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2006;347(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gower TL, Graham BS. Antiviral activity of lovastatin against respiratory syncytial virus in vivo and in vitro . Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45(4):1231–1237. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1231-1237.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Katano H, Pesnicak L, Cohen JI. Simvastatin induces apoptosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines and delays development of EBV lymphomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101(14):4960–4965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bader T, Korba B. Simvastatin potentiates the anti-hepatitis B virus activity of FDA-approved nucleoside analogue inhibitors in vitro . Antiviral Res. 2010;86(3):241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2010.02.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mihaila RG, Nedelcu L, Fratila O, et al. Effects of simvastatin in patients with viral chronic hepatitis C. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58(109):1296–1300. doi: 10.5754/hge08074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Z, Guo Z, Wang G, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of a statin/caffeine combination against H5N1, H3N2 and H1N1 virus infection in BALB/c mice. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009;38(3):215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Radigan KA, Urich D, Misharin AV, et al. The effect of rosuvastatin in a murine model of influenza A infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):E35788. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heinzel FP, Sadick MD, Holaday BJ, Coffman RL, Locksley RM. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169(1):59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Srivastava B, Blazejewska P, Hessmann M, et al. Host genetic background strongly influences the response to influenza a virus infections. PLoS One. 2009;4(3):E4857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. The pathology of influenza virus infections. Ann. Rev. Pathol. 2008;3:499–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.154316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zarogiannis SG, Noah JW, Jurkuvenaite A, Steele C, Matalon S, Noah DL. Comparison of ribavirin and oseltamivir in reducing mortality and lung injury in mice infected with mouse adapted A/California/04/2009 (H1N1) Life Sciences. 2012;90(11–12):440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, et al. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. 2009;460(7258):1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature08260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Walsh KB, Teijaro JR, Wilker PR, et al. Suppression of cytokine storm with a sphingosine analog provides protection against pathogenic influenza virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(29):12018–12023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107024108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marsolais D, Hahm B, Walsh KB, et al. A critical role for the sphingosine analog AAL-R in dampening the cytokine response during influenza virus infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(5):1560–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812689106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marsolais D, Hahm B, Edelmann KH, et al. Local not systemic modulation of dendritic cell S1P receptors in lung blunts virus-specific immune responses to influenza. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74(3):896–903. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lau YF, Tang LH, Ooi EE. A TLR3 ligand that exhibits potent inhibition of influenza virus replication and has strong adjuvant activity has the potential for dual applications in an influenza pandemic. Vaccine. 2009;27(9):1354–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lau YF, Tang LH, Ooi EE, Subbarao K. Activation of the innate immune system provides broad-spectrum protection against influenza A viruses with pandemic potential in mice. Virology. 2010;406(1):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evseenko VA, Bukin EK, Zaykovskaya AV, et al. Experimental infection of H5N1 HPAI in BALB/c mice. Virol. J. 2007;4:77. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cheng X, Xu Q, Song E, Yang CF, Kemble G, Jin H. The hemagglutinin protein of influenza A/Vietnam/1203/2004 (H5N1) contributes to hyperinduction of proinflammatory cytokines in human epithelial cells. Virology. 2010;406(1):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.CDC. Biosafety. www.cdc.gov/OD/ohs/biosfty/bmbl5/bmbl5toc.htm.

- 102.US Government Printing Office. Animals and Animal Products. www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_06/9cfr121_06.html.