Pulse-chase labeling of isolated yeast mitochondria identifies new assembly intermediates of Cox1p, characterizes their compositions, and orders them sequentially. The results indicate that cytochrome oxidase is assembled from separate modules, each consisting of different mitochondrial and nuclear gene products.

Abstract

Previous studies of yeast cytochrome oxidase (COX) biogenesis identified Cox1p, one of the three mitochondrially encoded core subunits, in two high–molecular weight complexes combined with regulatory/assembly factors essential for expression of this subunit. In the present study we use pulse-chase labeling experiments in conjunction with isolated mitochondria to identify new Cox1p intermediates and place them in an ordered pathway. Our results indicate that before its assimilation into COX, Cox1p transitions through five intermediates that are differentiated by their compositions of accessory factors and of two of the eight imported subunits. We propose a model of COX biogenesis in which Cox1p and the two other mitochondrial gene products, Cox2p and Cox3p, constitute independent assembly modules, each with its own complement of subunits. Unlike their bacterial counterparts, which are composed only of the individual core subunits, the final sequence in which the mitochondrial modules associate to form the holoenzyme may have been conserved during evolution.

INTRODUCTION

Cytochrome oxidase (COX), the terminal enzyme of many bacterial and all mitochondrial respiratory chains, catalyzes the transfer of electrons from cytochrome c to molecular oxygen, a reaction that is coupled to proton translocation across the membrane. In yeast, mitochondrial COX is composed of 11 distinct subunit polypeptides, three of which, making up the catalytic core, are encoded in mitochondrial DNA. The other eight subunits, with still poorly defined functions, are products of nuclear genes that are imported from the cytosol. The manner in which expression of COX subunits derived from two compartmentally separated genomes is temporally regulated and the mechanism by which they assemble into the holoenzyme have become the focus of studies in a number of laboratories (Carr and Winge, 2003; Perez-Martinez et al., 2009; Mick et al., 2011; Soto et al., 2012). A related area of active research is the process by which the catalytic subunits of the enzyme acquire the metal and heme prosthetic groups at their active centers (Cobine et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2012).

A key discovery that has provided much of the impetus for these studies is the role played by Cox1p in both regulation and assembly of the enzyme. Biogenesis of this important catalytic subunit is modulated by Mss51p and Cox14p, both of which interact with Cox1p to form a high–molecular weight complex (Perez-Martinez et al., 2003, 2009; Barrientos et al., 2004). When Mss51p is part of this complex, it is prevented from carrying out its normal function as a translational activator of the Cox1p mRNA. It was proposed that dissociation of the complex is triggered by a downstream event causing the release of Cox1p for assembly into COX and of Mss51p to initiate new rounds of Cox1p translation (Barrientos et al., 2004; Perez-Martinez et al., 2009). This regulatory loop is similar to the mechanism referred to as “control by epistasis of synthesis,” which was shown to adjust the translation rate of certain chloroplast gene products commensurate with their assembly into enzyme complexes of the photosynthetic system (Choquet et al., 2001).

More recent experiments on COX regulation have used pull-down assays and mass spectroscopy of Cox1p complexes under steady-state conditions to identify additional proteins that interact with Cox1p. Among the new components ascertained to be part of the Cox1p complex are Coa1p, Coa2p, and Shy1p (Pierrel et al., 2007, 2008; Mick et al., 2007), Coa3p/Cox25p and Ssc1p (Fontanesi et al., 2010, 2011; Mick et al., 2010), and Cox5ap (Mick et al., 2010). These findings suggest a more intricate mechanism of COX regulation than originally envisioned. This is also supported by the discovery that Mss51p can exist in at least three different states. In one, it is associated with Ssc1p but not Cox1p (Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010) and is active in promoting translation of Cox1p. In the other two states, Mss51p is present in larger complexes of Cox1p with other factors and can be either translationally active or inactive, depending on the presence or absence of Coa1p (Mick et al., 2011). Mss51p and Ssc1p, together with its chaperone Mdj1p, have also been proposed to be associated with mitochondrial ribosomes in a high–molecular weight translational complex during the elongation phase of Cox1p translation (Fontanesi et al., 2010).

In the present study we seek to gain additional insights into the assembly pathway of newly translated Cox1p in isolated mitochondria. Pulse and pulse-chase analysis of mitochondrial gene products combined with pull-down assays of tagged Cox1p enable us to identify and characterize the compositions of several new intermediates and link them kinetically in a pathway culminating in COX. On the basis of these and other results, we propose that Cox1p interacts with a subset of the nuclear-encoded subunits separately from Cox2p and Cox3p, the other two core subunits of COX. In this model, COX is composed of separate assembly modules, not unlike what was recently described for the ATP synthase (Rak et al., 2011).

RESULTS

Expression of Cox1p with a double-hemagglutinin plus protein C or polyhistidine tag

aMRSIo/COX1-HA and aMRSIo/COX1-HAC, harboring a mitochondrial copy of COX1 with an HA or double-hemagglutinin (HA) plus protein C tag, respectively, grew normally on respiratory substrates and contained wild-type levels of COX, as evidenced by their cytochromes a and a3 spectra, and translation of mitochondrial gene products (Supplemental Figure S1, A–C). aMRSIo/COX1-HAC was used to obtain almost completely pure cytochrome oxidase from a lauryl maltoside extract of mitochondria by a single affinity purification step on protein C antibody beads (Supplemental Figure S1D), indicating that the C-terminal tag is available to the antibody in the holoenzyme. MRSIo/COX1-HAH, a strain expressing Cox1p with a double-HA and polyhistidine tag (HAH) at the C-terminus of Cox1p, also grew like wild type (Supplemental Figure S1A) but displayed a 20% reduction in COX activity.

Pull-down assays of newly translated Cox1p-HAC

Yeast strains expressing Cox1p-HAC were used to analyze assembly intermediates of COX in mitochondria by pulse labeling. aMRSIo/COX1-HAC was grown to early stationary phase in YPGal with and without an additional 2 h of growth in the presence of chloramphenicol to increase mitochondrial pools of nuclear-encoded proteins (Tzagoloff et al., 2004; Rak et al., 2011). Digitonin extracts of labeled mitochondria were purified with an antibody to the protein C epitope coupled to agarose beads. Almost all of the newly translated Cox1p-HAC, but only a fraction of Cox3p, and even less of Cox2p in the digitonin extract, was recovered in the eluate from the antibody beads (Figure 1A, top). The eluate obtained from control mitochondria (aMRSIo) with untagged Cox1p had only background levels of radiolabeled proteins. Similar results were obtained with mitochondria from cells that had been grown for 2 h in chloramphenicol, except that cytochrome b also copurified with Cox1p-HAC (Figure 1A, bottom).

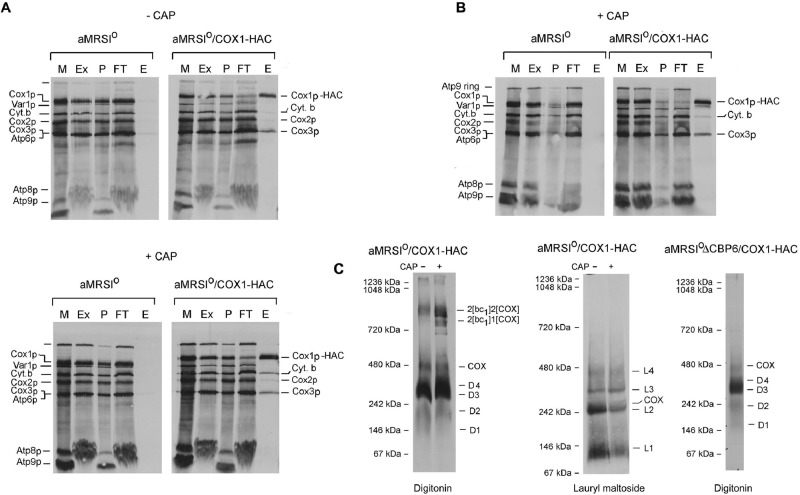

FIGURE 1:

Analysis of Cox1p complexes in isolated mitochondria. (A) aMRSIo and aMRSIo/COX1-HAC were grown to early stationary phase in YPGal. Cells from one-half of the cultures were used to prepare mitochondria. The other half was inoculated into the starting volumes of fresh YPGal containing 2 mg/ml chloramphenicol, and growth was continued for an additional 2 h before preparation of mitochondria. Mitochondria (500 μg of protein) were labeled at 24°C with a mixture of [35S]methionine and cysteine (Rak et al., 2011). After 20 min, unlabeled methionine and cysteine were added to final concentrations of 1.6 and 0.8 mM, respectively. Mitochondria were centrifuged at 10,000 × gav for 10 min, washed with 0.4 ml of buffer containing 0.6 M sorbitol and 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7, and suspended at a protein concentration of 10 mg/ml in extraction buffer containing 3% digitonin, 150 mM potassium acetate, 2 mM α-aminocaproic acid, and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7. The suspension was centrifuged at 100,000 × gav for 10 min, and the supernatant (74 μl) was added to 100 μl of packed protein C antibody beads that had been prewashed with wash buffer. The beads were rotated at 4°C for 90 min, centrifuged, and washed three times with 0.5% digitonin in wash buffer. Proteins were eluted by rotation of the washed beads at 4°C for 30 min with 100 μl of elution buffer containing 0.5% digitonin. The following fractions were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17% polyacrylamide gel: E, eluate from the beads; Ex, digitonin extract; FT, protein fraction that did not adsorb to the antibody beads; M, mitochondria; P, pellet after digitonin extraction. All of the fractions loaded on the gel were adjusted to the starting volume of mitochondria (equivalent to 20 μg of protein). (B) aMRSIo and aMRSIo/COX1 were grown as in A with a 2-h incubation in medium containing chloramphenicol. The mitochondria were labeled and fractionated as in A, except that the extraction buffer contained 1% lauryl maltoside instead of digitonin and the antibody beads were washed and eluted in the presence of 0.2% lauryl maltoside. (C) Eluates of the samples obtained from mitochondria grown in the presence and absence of chloramphenicol were mixed with 0.14 volume of 7× sample buffer (Wittig et al., 2006) and separated by BN-PAGE. The sample shown in the extreme right was obtained from a cbp6 mutant (aMRSIoΔCBP6/COX1-HAC) grown in the absence of chloramphenicol.

When analyzed by blue native PAGE (BN-PAGE), newly translated Cox1p-HAC recovered from the antibody beads separated into several bands of different size (Figure 1C). The slowest-migrating bands corresponded to supercomplexes containing the bc1 dimer (complex III) with either two or one COX complexes. At least five other radiolabeled bands with approximate sizes of 450 (COX dimer), 350 (D4), 300 (D3), 200 (D2), and 150 (D1) kDa were also detected in the protein C eluates purified from chloramphenicol-treated and untreated cells. With the exception of the supercomplexes, the same bands were labeled in a cbp6 mutant (Figure 1C, right) blocked in assembly of the bc1 complex (Dieckmann and Tzagoloff, 1985).

Mitochondria of chloramphenicol-treated cells were also extracted with lauryl maltoside, and Cox1p-HAC was purified on the protein C antibody beads. This detergent achieved a more complete solubilization of the labeled products than digitonin, but the ratio of Cox1p-HAC to Cox3p was the same as in the digitonin extract (Figure 1B). There was considerably less cytochrome b eluted from the antibody beads. The antibody-purified fraction separated into several radiolabeled bands on native gels, most of which were smaller than those extracted and purified in the presence of digitonin (Figure 1C, middle). No radiolabel was detected in the region of the supercomplexes, which are dissociated by lauryl maltoside.

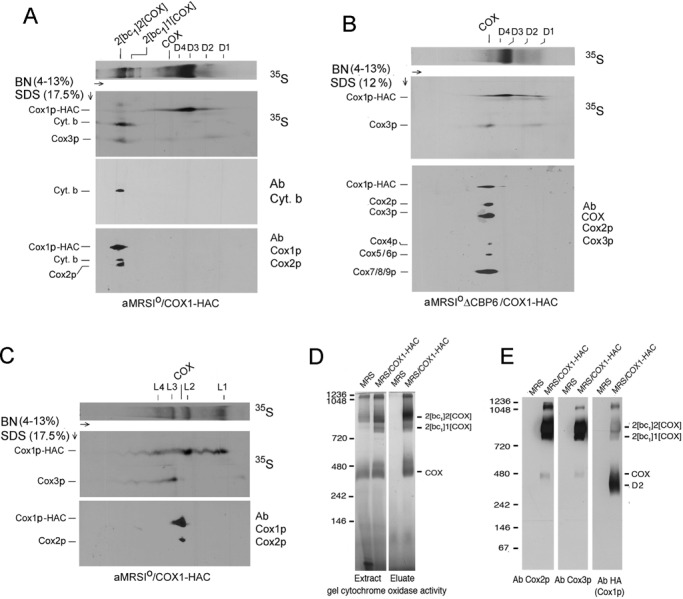

The newly translated products associated with the bands detected by BN-PAGE were also analyzed by SDS–PAGE in a second dimension. The two-dimensional (2D) gel revealed Cox3p and cytochrome b as the major radiolabeled proteins present in the supercomplexes of digitonin-extracted mitochondria from chloramphenicol-treated cells (Figure 2A). The presence of cytochrome b was confirmed immunochemically (Figure 2A, bottom). Most of the radiolabeled Cox3p in the eluate was present in the supercomplexes and a smaller fraction in the 450-kDa band corresponding to COX (Figure 2A). Cox3p was not present in the D2, D3, or D4 subcomplex. Some Cox3p migrated as a diffuse band overlapping with D1. This might be some Cox3p that binds nonspecifically to the agarose beads. Although radiolabeled Cox1p-HAC and Cox2p were also present in the supercomplexes, their concentrations were lower than that of Cox3p. Similar results were obtained when the source of mitochondria was a strain expressing Cox1p with a C-terminal HA and polyhistidine tag and the digitonin extract purified on nickel nitriloacetic acid (Ni-NTA) instead of protein C antibody beads (unpublished data).

FIGURE 2:

Two-dimensional BN- and SDS–PAGE analysis of radiolabeled Cox1p complexes. (A) Mitochondria were prepared from aMRSIo/COX1-HAC grown in YPGal to early stationary phase and transferred for 2 h to fresh YPGal medium containing 2 mg/ml chloramphenicol. Mitochondria labeled with [35S]methionine plus cysteine for 20 min were extracted with digitonin and the extracts purified on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. Proteins were separated by BN-PAGE in the first dimension. A strip of the first dimension gel was soaked for 30 min in a buffer containing 0.1% SDS and 100 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.8, and was layered on top of a 17% SDS-polyacrylamide gel for separation in the second dimension (Laemmli, 1970). Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and exposed to x-ray film. The radiolabeled band migrating midway between Cox1p and Cox3p in the region corresponding to the supercomplexes was confirmed to be cytochrome b by Western analysis (bottom). (B) Same as A, except that mitochondria were obtained from the cbp6 mutant aMRSIoΔCBP6/COX1-HAC grown in the absence of chloramphenicol. After autoradiography the gel was treated sequentially with 1) a polyclonal antibody against yeast cytochrome oxidase, 2) a monoclonal antibody against Cox2p, and 3) a monoclonal antibody against Cox3p. The COX antibody detects Cox1p and Cox4-9. (C) Same as A, except that the labeled mitochondria were extracted with lauryl maltoside as in Figure 1B. (D) Digitonin extracts of mitochondria from MRS-3B and MRS/COX1-HAC were fractionated on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. Extracts and eluates from 50 and 170 μg of starting mitochondria protein were separated by BN-PAGE. The gel was immersed in a solution containing 0.5 mg/ml DAB and 1 mg/ml horse heart cytochrome c for several hours. The reaction was stopped with 45% methanol/5% acetic acid. Molecular weight markers were visualized by Coomassie R-250 staining after documentation of the in-gel activity. (E) Digitonin extracts of mitochondria from MRS-3B and MRS/COX1-HAC were solubilized in 3% digitonin and fractionated on protein C antibody beads. Eluates equivalent to 450 μg of starting mitochondrial protein were separated by BN-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and reacted with antibodies against Cox2p and Cox3p. The Cox3p immunoblot was stripped and reprobed with anti-HA antibody to detect Cox1p-HAC.

The 2D gels of the cbp6 mutant lacking the bc1 complex indicated that most of the radiolabeled Cox3p band migrated close to the 480-kDa marker. This band is probably a COX dimer, based on its size and composition, which includes both mitochondrially and nuclear-encoded subunits of COX (Figure 2, B and E) and the presence of COX activity when tested by an in-gel assay with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and cytochrome c (Figure 2D). Radiolabeled Cox1p-HAC and Cox3p were also detected in the region of dimeric COX in aMRSIo/COX1-HAC, a respiratory-competent strain containing the bc1 complex, but their concentrations were much lower than in the cbp6 mutant (Figure 2, A and B). This was also evident when the protein C antibody eluate from aMRSIo/COX1-HAC was separated by BN-PAGE and the blot probed with antibodies against Cox2p, Cox3p, and the HA tag to detect Cox1p-HAC (Figure 2E).

The second dimension of the lauryl maltoside extract had no detectable radiolabeled cytochrome b (Figure 2C). Most of newly translated Cox3p, together with much less Cox1p-HAC, was associated with L2 and L4. In contrast, Cox1p-HAC was present largely in L2 and L1. The relationship of these bands to those observed in the comparable fraction purified from the digitonin extract has not been determined. A small fraction of both Cox1p-HAC and Cox3p migrated with a band just above the 242-kDa marker, which, based on the presence of immunochemically detectable Cox1p and Cox2p, is probably monomeric COX (Figure 2C).

The mitochondria used in these experiments were prepared from late-log-phase/early-stationary-phase cells. Similar results were obtained when aMRSIo/COX1-HAC was grown to early log, mid log, and late log/early stationary phase (Supplemental Figure S2, A–D).

Kinetics of incorporation of Cox1p-HAC into COX subcomplexes

Of the six major products detected by SDS–PAGE, cytochrome b and Cox3p appeared to be most rapidly labeled (Figure 3A). An unidentified product, indicated by the asterisk in Figure 3A, was maximally labeled in the first minute of translation. The fractions eluted from the antibody beads revealed that Cox3p associates with Cox1p-HAC before cytochrome b (Figure 3, A and C).

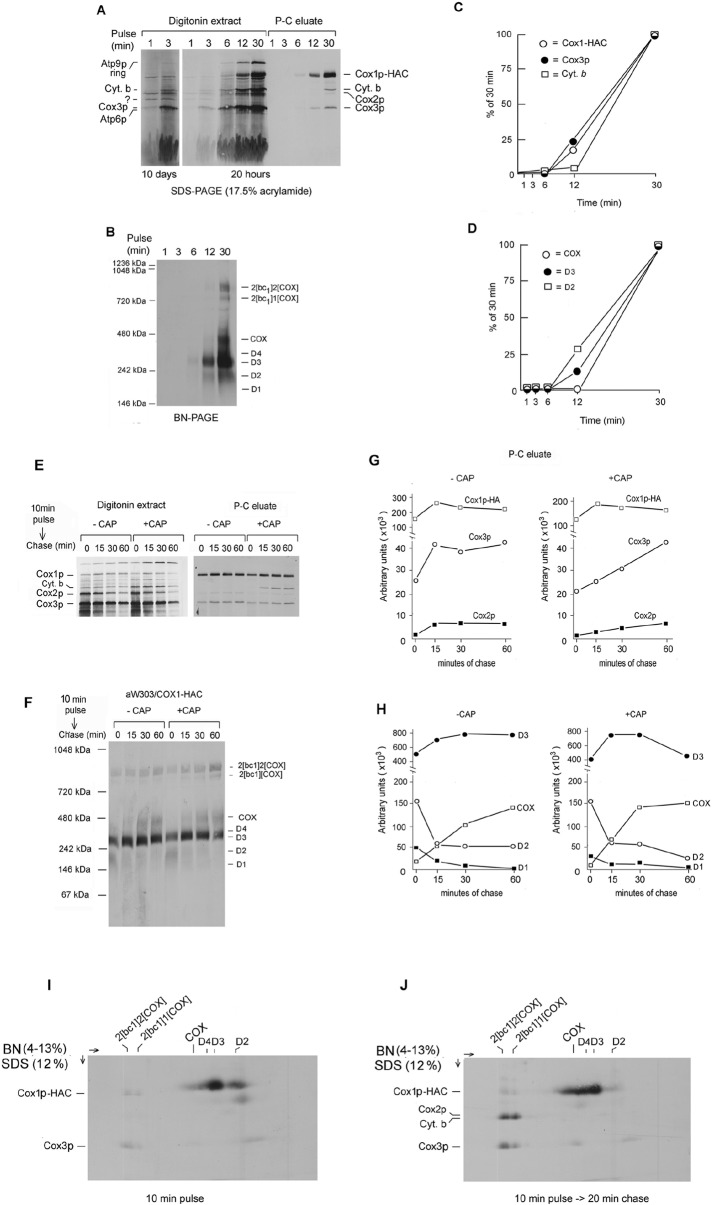

FIGURE 3:

Kinetics of Cox1p-HAC incorporation into COX subcomplexes. (A) aMRSIo/COX1-HAC mitochondria were labeled with [35S]methionine plus cysteine for the indicated times and immediately added to an equal volume of 4% digitonin in extraction buffer and centrifuged. The digitonin extracts were further purified on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. Samples of the extracts and eluates from the beads were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and exposed to x-ray film for 20 h and for 10 d. (B) The eluates from the antibody beads were separated by BN-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membrane, and exposed to x-ray film. (C) Cox1p-HAC, Cox3p, and cytochrome b eluted from the antibody beads were quantified with a PhosphorImager. The results are plotted as percentage of the values obtained at 30 min. (D) The bands corresponding to COX, D2, and D3 were quantified as in C. (E) aMRSIo/COX1-HAC was grown to late–log phase in YPGal. Cells were harvested and equal parts inoculated into fresh YPGal without (–CAP) and with 2 mg/ml chloramphenicol (+CAP). The cultures were grown for an additional 2.5 h before preparation of mitochondria. Mitochondria equivalent to 250 μg of protein in a final volume of 80 μl were labeled for 10 min at 24°C with [35S]methionine plus cysteine. Translation was terminated by addition of puromycin to a final concentration of 100 μM, and a sample (0 time) representing 25% of the total translation mix was added to 1.2 volumes of 4% digitonin in extraction buffer and centrifuged at 100,000 × gav for 10 min. Identical-size samples were extracted with digitonin after 15, 30, and 60 min of incubation at 24°C. Digitonin extracts and eluates from the protein C antibody beads, representing 5 and 25% of the starting material, respectively, were separated by SDS–PAGE and radiolabeled proteins visualized as in A. (F) The remainder of the eluates from the antibody beads were separated by BN- PAGE and radiolabeled proteins visualized as in B. (G) The radiolabeled bands corresponding the Cox1p-HAC, Cox2, and Cox3 in the protein C eluates were quantified as in C. (H) The bands identified as COX and the three subcomplexes D2, D3, and D4 of the native gel shown in Figure 3F were quantified with a PhosphorImager as in D. (I, J) Mitochondria from aMRSIo/COX1-HAC were labeled at 24°C with [35S]methionine and cysteine for 10 min. Translation was terminated by addition of puromycin. After incubation for an additional 20 min mitochondria were extracted with digitonin as in E, and Cox1p-HAC was purified on the antibody beads. The eluates from the beads were separated by BN-PAGE on a 3–14% polyacrylamide gel in the first dimension and by SDS–PAGE on a 17% gel in the second dimension. Proteins were transferred to PVDF and visualized by exposure to x-ray film.

The precursor–product relationship of the D1–D4 subcomplexes to COX was examined by quantifying their relative rates of labeling over a period of 1–12 min as percentages of the values measured at 30 min. Newly translated Cox1p-HAC was present almost exclusively in COX and the D2–D4 subcomplexes (Figure 3B). D2 was the most rapidly labeled, followed by D3 and then COX (Figure 3, B and D). This suggests that D2 is a precursor of D3 and COX. The incomplete separation of D4 from D3 and the poor labeling of D1 in this experiment made them difficult to quantify. Incorporation of newly translated cytochrome b into the supercomplexes increased with time of labeling but was slower than that of Cox3p (Figure 3, A and C). The slower kinetics of cytochrome b incorporation into the supercomplexes compared with Cox3p may be deceptive in view of the presence of Cox3p in COX and another uncharacterized complex in the region of D1.

Pulse-chase experiments also support a role of D2 (and D1) as precursors of the larger D3 subcomplex and of COX. After labeling of mitochondria for 10 min, translation was quenched by addition of puromycin, and radiolabeled products were chased for up to 1 h before extraction and purification of Cox1p-HAC–containing complexes. Puromycin effectively terminated translation and cleared the background of unfinished polypeptide chains present in the nonchased sample (Figure 3E). Some increase in radiolabeled Cox1p-HAC recovered from the antibody beads occurred during the first 15 min of chase but decreased subsequently, probably as a result of turnover (Figure 3, E and G). Newly translated Cox2p and Cox3p also decreased during the chase. This was more evident in mitochondria of cells that had been treated with chloramphenicol (Figure 3E). The relative abundance of the supercomplexes and subcomplexes in the antibody-purified fractions was assessed by BN-PAGE. Visual inspection and quantification of the gel disclosed an increase in radiolabel associated with the supercomplexes and COX over the course of the chase. D3 labeling also increased after 15 and 30 min of chase but was reduced at 60 min, perhaps as a result of combined conversion to COX and turnover. In contrast, D2 and D1 progressively lost label in mitochondria of chloramphenicol-treated and untreated cells (Figure 3, F and H). The precursor–product relationship of Cox1p-HAC in D2–D4 and in COX and the supercomplexes was confirmed from the 2D gels of the proteins pulled down from extracts of mitochondria pulsed for 10 min with and without a subsequent 30-min chase (Figure 3I). Most of Cox1p-HAC after the pulse was present in D2 and D3, with only trace amounts in COX and the supercomplexes. After the 30-min pulse, the loss of Cox1p-HAC in D2 was accompanied by an increase of radiolabeled Cox1p-HAC in D4, COX, and the supercomplexes (Figure 3J).

The pulse-chase experiment was repeated with the cbp6 mutant MRSIoΔCBP6/COX1-HAC. Mitochondria were labeled for 10 min and chased for up to 60 min after addition of puromycin. The native gel of the antibody eluates indicated an increase in D3 during the first 15 min of chase and a progressive increase radiolabel in COX, similar that what was found with MRSIo/COX1-HAC (Supplemental Figure S3). No radiolabel was present in the supercomplex region, as this strain is deficient in the bc1 complex. The 2D gel of the eluate from the pulsed but not chased mitochondria showed that almost all the radiolabel was associated with Cox1p-HAC in COX and D4–D2. In contrast, the 30-min chase resulted in the incorporation of Cox3p into COX and the loss of radiolabel in the band corresponding to the D2 precursor (Supplemental Figure S3).

Compositions of the D1–D4 intermediates

The results discussed in the preceding sections indicate the absence of newly translated Cox2p in D1–D4 and of Cox3p in D2–D4. To further characterize the four Cox1p intermediates, we integrated fusion genes expressing Cox4p, Cox5ap, Cox6p, and Cox9p (subunit 7a) with C-terminal HAC double tags into nuclear DNA of the respective null mutants. The resultant strains were rescued for growth on rich glycerol/ethanol, indicating that the presence of the tags did not compromise the functions of the different subunits (Figure 4, A and B).

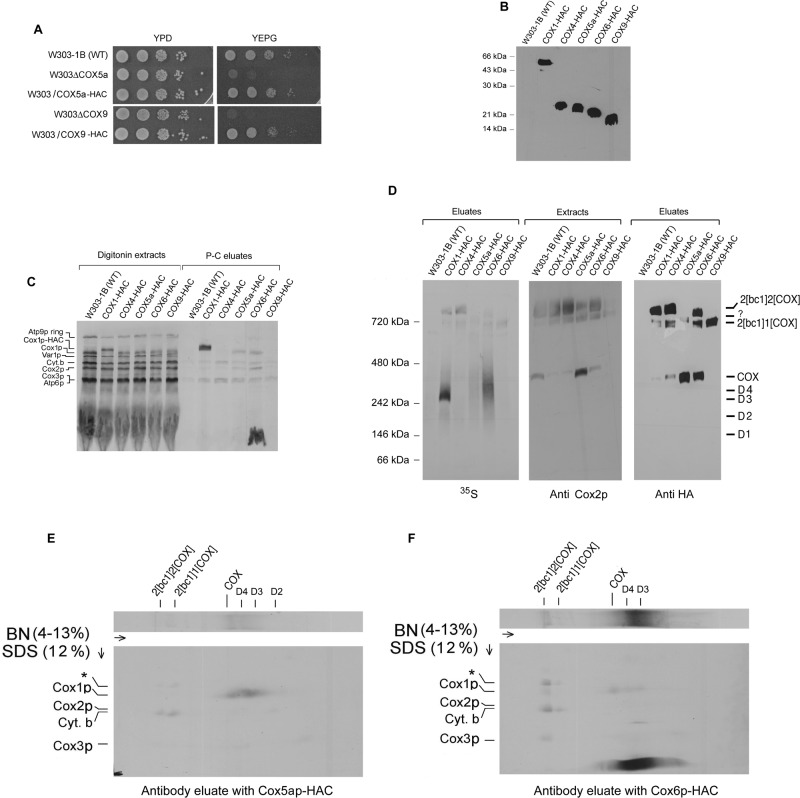

FIGURE 4:

Subunit composition of Cox1p intermediates. (A) Serial dilutions of the wild-type W303-1B, a cox5a (W303ΔCOX5a)- and a cox9 (W303ΔCOX9)-null mutant, and null mutants expressing HAC-tagged Cox5ap and Cox9p were serially diluted and spotted on rich glucose (YPD) and rich glycerol plus ethanol (YEPG) plates. The plates were photographed after 2 d at 30°C. (B) Mitochondria (12.5 μg of protein) from W303-1B and strains of yeast expressing Cox4p, Cox5ap, Cox6p, and Cox9p with C-terminal HAC double tags were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope as in Figure 2A. (C) Mitochondria were labeled for 20 min at room temperature with [35S]methionine and cysteine. Translation was terminated with puromycin, and incubation continued for an additional 10 min. The labeled mitochondria were extracted by addition of 1.2 volumes of 4% digitonin and tagged subunits purified on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. Samples of extracts and eluates were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17% polyacrylamide gel. (D) The digitonin extracts and eluates obtained in C were separated by BN-PAGE. After transfer to PVDF, the blot with the eluates was first exposed to x-ray film and then probed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against the HA epitope. The blot with the extracts was immunostained with a monoclonal antibody against Cox2p. (E, F) The eluates with Cox5ap-HAC and Cox6p-HAC were separated by BN-PAGE in the first dimension and by SDS–PAGE in the second dimension. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and exposed to x-ray film.

Mitochondria of strains expressing one of the four tagged subunits were labeled and digitonin extracts analyzed by SDS- and BN-PAGE following purification of Cox1p-HAC complexes on protein C antibody beads. Whereas newly translated Cox1p, Cox2p, and Cox3p copurified with tagged Cox5ap and Cox6p, only radiolabeled Cox3p and cytochrome b were detected in SDS–PAGE gel of the eluate purified from the strain with the tagged Cox4p (Figure 4C). The radiolabel associated with the smaller Cox9p subunit was not significantly above the background of the control wild-type W303 strain (Figure 4C). Unexpectedly, the eluate purified from mitochondria with Cox6p-HAC contained a strong radiolabeled band that migrated as the Atp9p subunit of the ATP synthase in SDS–PAGE (Figure 4C).

The native gel of the same eluates showed that all contained radiolabeled supercomplexes. Moreover, eluates obtained from strains expressing Cox1p-HAC, Cox5ap-HAC, and Cox6p-HAC also had significant radioactivity in the region spanning D3 and COX (Figure 4D, left). The 2D gels of the eluates with Cox5ap-HAC and Cox6p-HAC confirmed that both had radiolabeled D2 (with Cox5ap-HAC only), D3, D4 and COX but not D1 (Figure 4, E and F). These results are consistent with the presence of Cox5ap in D2, D3, D4, and COX and of Cox6p in D3, D4, and COX but not in D1 or D2. The 2D gel with the eluate containing Cox5ap-HAC revealed the presence of radiolabeled cytochrome b, trace amounts of Cox1p and Cox3p, and a novel band migrating above Cox1p (asterisk in Figure 4, E and F) in the supercomplex region. The same bands including Cox2p were present in the supercomplex region of the Cox6p-HAC eluate. However, there was substantially more Cox1p and Cox3p associated with the supercomplexes in the eluate with Cox6p-HAC than with Cox5ap-HAC, probably because of lesser accessibility of the latter to the antibody. The tag on Cox5ap, which is located at the interface of COX and the bc1 complex (Heinemeyer et al., 2007; Mileykovskaya et al. 2012), might be masked in the supercomplex but not in COX or Cox1p intermediates. The Cox9p-HAC eluate contained supercomplex with a single COX (this was also the only supercomplex detected with antibodies against Cox2p and the HA tag) but was deficient in radiolabeled D1–D4, indicating that this subunit is not present in the Cox1p intermediate complexes. The C-terminal modification of Cox9p might therefore partially inhibit COX assembly.

FIGURE 5:

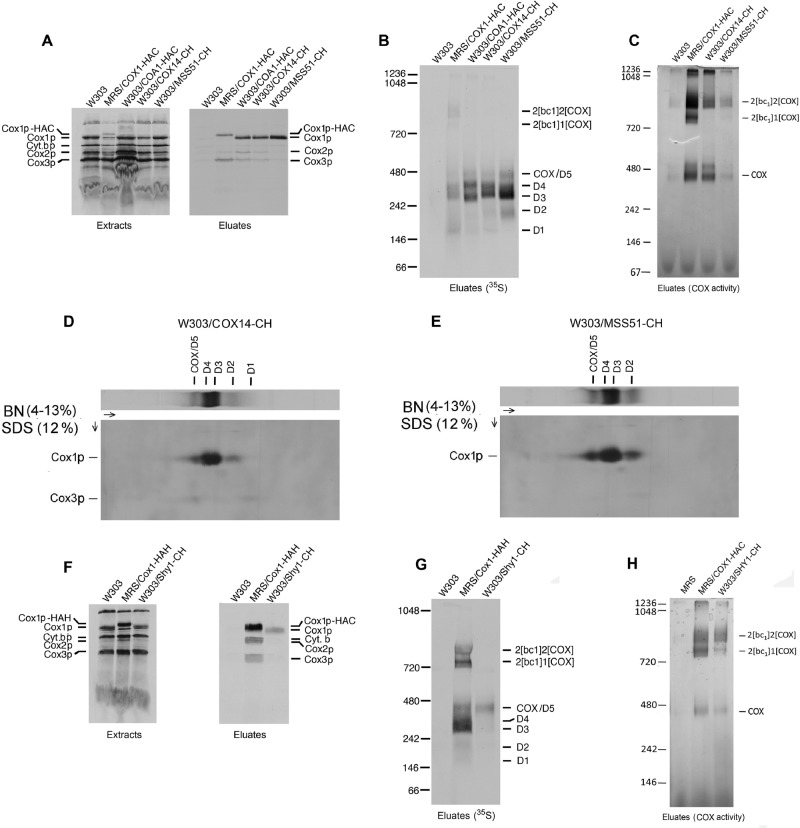

Analysis of Cox14p, Mss51p, Coa1p, and Shy1p in the Cox1p intermediates. W303-1B, MRS/COX1-HAC, W303/COA1-HAC, W303/COX14-CH, and W303/MSS51-CH were grown in YPGal and mitochondria labeled with [35S]methionine plus cysteine. Puromycin was added after 30 min, and incubation continued for an additional 10 min. Mitochondria (450 μg of protein) were extracted with digitonin and the tagged proteins purified on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. Radiolabeled mitochondrial gene products were visualized after separation of the digitonin extracts and eluates on a 17% polyacrylamide gel by SDS–PAGE (A) and BN-PAGE (B). (C) The eluates from the antibody beads were separated by BN-PAGE and stained for COX activity as in Figure 1D. (D, E) Mitochondria were labeled and extracted with digitonin, and the extracts were purified on antibody beads as in A. Eluates from the beads were separated by 2D gel electrophoresis. Proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and exposed to x-ray film. (F) Mitochondria from W303-1B, MRS/COX1-HAH, and W303/SHY1-CH were labeled and extracted as in A. The digitonin extracts were incubated with Ni-NTA beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for 2 h in the presence of 400 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 0.5% digitonin, pH 8.0. The resin was washed three times in the same buffer and proteins eluted with 150 mM imidazole, pH 7.4, in 0.5% digitonin. Samples of the extracts and eluates were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17.5% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and exposed to x-ray film. (G) The eluates from Ni-NTA were separated by BN-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane and exposed to x-ray film. (H) Mitochondria from W303-1B, MRS/COX1-HAH, and W303/SHY1-CH were extracted as in C. The digitonin extracts were incubated with Ni-NTA resin and eluted as in F and stained for COX activity as in C.

Most of the label between the COX and D1 region of the COX6p-HAC strain was present in a mitochondrial product that migrated as the Atp9p monomer when separated by SDS–PAGE in the second dimension (Figure 4F). This protein was absent in a Cox6p-HAC pull down of an atp25-null mutant blocked in expression of Atp9p (Zeng et al., 2008) but was present in the eluate of an mss51-null mutant expressing Cox6p-HAC (unpublished data). This indicates that the interaction of newly translated Atp9p with Cox6p-HAC occurs independent of Cox1p or COX.

Relationship of the D1–D4 to previously described Cox1 complexes

The most abundant Cox1p assembly intermediate has been reported to have a size of 450 kDa measured by sucrose gradient sedimentation (Fontanesi et al., 2010) and of 440 kDa (Pierrel et al., 2007) or 230 kDa when estimated by BN-PAGE (Mick et al., 2010). The presence of Cox1p in this complex was shown directly by coimmunoprecipitation with Cox14p, Mss51p, Ssc1p, Coa1, and Coa3p and indirectly by the absence of the complex in mitochondria of cox14, mss51, and coa3 mutants (Fontanesi et al., 2010; Khalimonchuk et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010). A second, less abundant Cox1p complex migrating just above the 230 or 440 kDa complex in blue native gels has also been reported (Pierrel et al., 2007; Khalimonchuk et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010). This complex was deduced to contain Coa1p in addition to Mss51p, Cox14p, and Cox3p (Mick et al., 2010). The relationship of these previously described Cox1p-containing complexes to those identified in this study was assessed by characterizing some of the accessory factors associated with D1–D4 by means of pull-down assays similar to those described in the preceding sections. For these studies we used strains expressing Mss51p, Cox14p, Shy1p, and Coa1p with a C-terminal protein C followed by a polyhistidine tag (CH) or with HA followed by a protein C tag (HAC).

In these studies radiolabeled Cox1p, Cox2p, and Cox3p were found to copurify with Cox14p-CH and Coa1p-HAC. This was also true of the eluate from the Cox1p-HAC control but not of Mss51p-CH, which contained only Cox1p (Figure 5A). The eluates separated on a blue native gel revealed that the major radiolabeled band in the Mss51p-CH and Cox14p-CH eluates corresponded to D3 (Figure 5B). D2, D4, and COX but not the supercomplexes were also labeled, confirming earlier evidence that Mss51p is not associated with COX in the supercomplexes (Pierrel et al., 2007; Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010). A major difference in the eluates from the Cox14p-CH and Mss51p-CH strains was the absence in the latter of D1 (Figure 5, B, D, and E). Although the eluate from the Coa1p-HAC strain displayed a similar pattern of radiolabeled bands, the migrations of D3 and D4 were slightly different. It is not clear whether this difference stems from the HAC tag on this subunit or from compositional differences. Mixing the Coa1p-HAC with the Cox14p or Mss51p-CH eluate, however, resulted in a fused pattern, suggesting that the two sets of bands were the same (unpublished data).

Two-dimensional gels of the eluates with Cox14p-CH and Mss51p-CH indicated the presence of Cox1p, Cox2p, and Cox3p in the COX band of Cox14p-CH but only of Cox1p in the same region of Mss51p-CH (Figure 5, D and E). This suggests that in addition to COX this region might contain an incompletely assembled COX intermediate. An in-gel enzyme assay confirmed the coimmunoprecipitation of COX with Cox1p-HAC and Cox14p-CH but not with Mss51p-CH, in which the activity stain was not significantly more than the background activity of W303 devoid of tagged protein (Figure 5C)

Insertion of heme A at the two redox centers of Cox1p is dependent on Shy1p (Khalimonchuk et al., 2010; Hannappel et al., 2012). It has been proposed that this protein interacts with newly translated Cox1p subsequent to formation of the Mss51p complex, and in some models of COX assembly this corresponds to the step at which Mss51p is released to promote a new round of Cox1p translation (Fontanesi et al., 2011). The association of Shy1p with the different complexes identified in this study was probed in a strain that expressed the protein with a C-terminal tag consisting of protein C followed by polyhistidine (Shy1p-CH). Shy1p-CH, adsorbed to Ni-NTA beads from labeled mitochondria, copurified only with newly translated Cox1p (Figure 5F). The radiolabeled Cox1p in this fraction migrated in the COX region of the native gel (Figure 5G). The absence of radiolabeled Cox2p and Cox3p in the Shy1p-enriched fraction further substantiates the presence of another intermediate in the COX region of the blue native gel, which is designated as D5 in Figure 5. In-gel assays of COX activity indicated that Shy1p is also associated with fully active COX itself and with the supercomplexes (Figure 5H).

The concentrations of D3 and D4 in aMRSIo/COX1-HAC are sufficiently high to be detected with an antibody against the HA tag. This was also true of a panel of COX mutants defective in expression of Cox2p, Cox3p, Cox4p, Cox5ap, Shy1p, and Cox10p (Supplemental Figure S4). In agreement with previous reports, both assembly intermediates were absent in a cox14 mutant. The presence of D3 and D4 in the cox10 mutant (Supplemental Figure S4) suggests that addition of heme A to Cox1p is not required for either formation or stability of these complexes and is consistent with the proposed interaction of Shy1p at a step subsequent to D4 to form a higher–molecular weight intermediate (D5) that comigrates with COX in native gels.

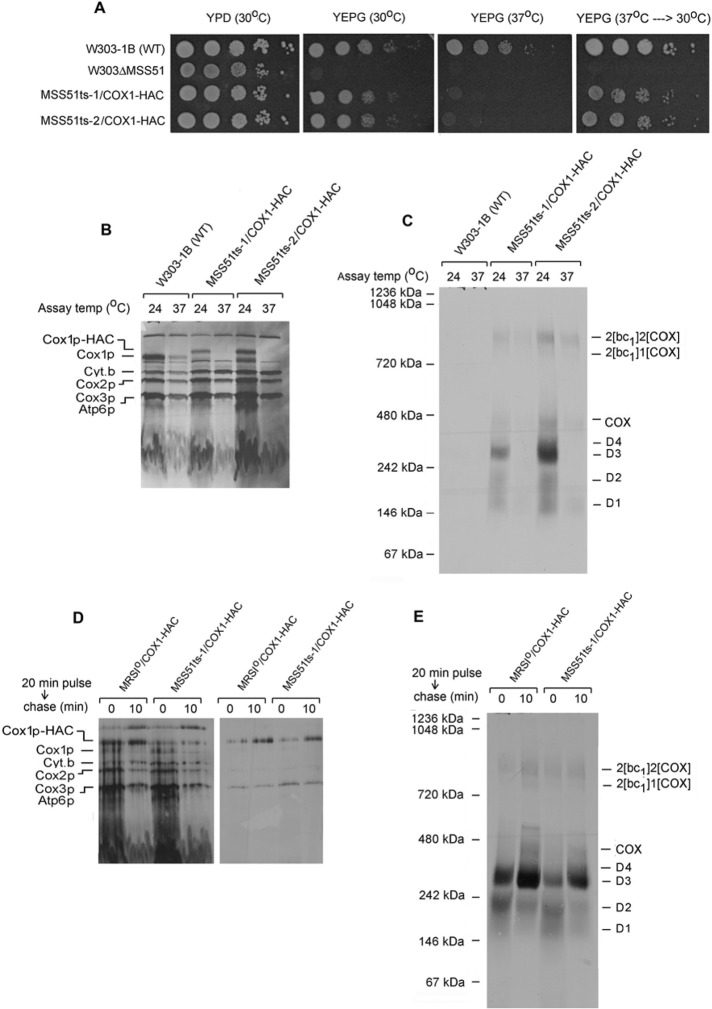

Cox1p intermediates in mss51 temperature-sensitive mutants

Temperature-sensitive (ts) mss51 mutants were used to further probe the function of Mss51p in assembly of COX. The mss51 ts alleles were obtained by mutagenic PCR amplification and were substituted for the wild-type gene in a strain expressing Cox1p-HAC. The ts mutants exhibited a reversible growth defect on respiratory substrates (Figure 6A) and did not translate Cox1p-HAC at 37°C (Figure 6B). Even though incorporation of newly translated Cox1p-HAC into the D1–D4 intermediates was completely blocked at the restrictive temperature, the large steady-state pools of D3 and D4 allowed some assembly of COX, as witnessed by the appearance of label in COX and the supercomplexes (Figure 6C). The ability of Cox1p-HAC to transition through its normal assembly pathway under restrictive conditions was also evident when mitochondrial gene products were labeled at the permissive temperature followed by a chase at the nonpermissive temperature. Translation of Cox1p-HAC in mitochondria of a strain with wild-type or mutant Mss51p at 24°C led to its incorporation into the smaller D1 and D2 intermediates and could be efficiently chased at 37°C into the larger D3 and D4 intermediates and into COX and the supercomplexes (Figure 6, D and E).

FIGURE 6:

Cox1p intermediates in an mss51 ts mutant. (A) Serial dilution of the wild-type W303-1B, the mss51-null mutant (W303ΔMSS51), and two independent mss51 ts mutants, MSS51ts-1/COX1-HAC and MSS51ts-2/COX1-HAC, were spotted on YPD and YEPG. The plates were incubated for 2 d at the indicated temperatures. The YEPG plate that had been incubated at 37°C was transferred to 30°C and incubated for an additional 2 d (far right). (B, C) Mitochondria were prepared from the wild-type strain W303-1B and the two mss51 ts mutants grown at 30°C. They were preincubated either at 24 or 37°C for 5 min before addition of [35S]methionine and cysteine and further incubated at the same temperatures for 30 min. Mitochondria were extracted with 1.2 volumes of 4% digitonin and the extracts purified on protein C antibody beads as in Figure 1A. The extracts were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17% polyacrylamide gel (B) and the eluates from the beads by BN-PAGE (C). Proteins were transferred either to nitrocellulose or a PVDF membrane and exposed to x-ray film. (D) Mitochondria from the wild-type strain MRSIo/COX1-HAC and from the mss51 ts mutant were labeled for 20 min at 24°C with [35S]methionine and cysteine. Puromycin was added, and incubation continued for another 10 min at 37°C before extraction with digitonin. The extracts were purified on antibody beads, and samples of extract and eluates were separated by SDS–PAGE on a 17% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and exposed to x-ray film. (E) The eluates from D were separated on a blue native gel, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and exposed to x-ray film.

DISCUSSION

COX assembly is an important aspect of the process by which mitochondrial function and morphology are maintained and modulated during cell growth and adaptation to changing environmental and physiological circumstances. In recent years a number of laboratories have studied this problem in baker's yeast because of the plentiful biochemical and genetic resources provided by this organism. The approaches taken have relied on analyzing assembly intermediates of COX under steady-state conditions, particularly as it applies to Cox1p, which is believed to play a central role not only in assembly, but also in coordinating and achieving a balanced output of COX polypeptides expressed from mitochondrial and nuclear genes. These studies have been instrumental in identifying two Cox1p assembly intermediates and in attaining an inventory of their constituent subunits and regulatory factors (Perez-Martinez et al., 2003; Barrientos et al., 2004; Pierrel et al., 2007; Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010).

In the present study we used a kinetic approach to gain additional insights into biogenesis of previously and newly identified Cox1p intermediates. These studies relied heavily on the use of strains expressing Cox1p with an affinity tag that is recognized by and easily dissociated from its antibody under nondenaturing conditions. Our interpretations of the results presented here are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Cox1p progresses through at least five intermediates, four of which are discernible on native gels, with a fifth (D5) that is not directly demonstrable because it comigrates with COX. This last is the largest intermediate that does not contain newly translated Cox3p, but it copurifies with Mss51p and Shy1p (Figure 5, D, E, and G).

-

2.

D3 and D4 are probably equivalent to the two Cox1p intermediates described in other studies (Pierrel et al., 2007; Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010). This is based on their immunochemical detection under steady-state conditions (Supplemental Figure S4) and cofractionation with Mss51p and Cox14p (Figure 5). Unlike Cox14p and Coa1p, which are associated with both D1 and D2, Mss51p is present in D2 but not D1. This suggests that Mss51p interacts with newly translated Cox1p subsequent to Cox14p and Coa1p.

-

3.

The kinetics of in organello labeling of mitochondrial gene products and pulse-chase analysis of the distribution of label in Cox1p intermediates, COX, and the supercomplexes indicate D2 (and D1) to be precursors of the larger and more abundant D3 (and D4) and the latter to be precursors of COX (Figure 3). The large increase of radiolabeled Cox1p in the COX region after a chase is probably contributed by D5 rather than COX, as the increase of radiolabel Cox1p in the supercomplexes is considerably less (Figure 3, I and J). There is more radiolabeled Cox3p than Cox1p in the supercomplexes after a chase. This can be explained by the large steady-state pools of D3 and D4 (Supplemental Figure S4), which effectively dilute radiolabeled Cox1p translated during the pulse. It is not excluded, however, that an exchange of newly translated Cox3p with fully assembled COX might also contribute to the aberrant stoichiometry.

Conversion of D2 and D1 to the larger D3 and D4 is relatively slow, as it can be resolved both kinetically and by pulse chase. Assembly of the Cox1p precursor with Cox2p and Cox3p, however, must be a rapid step, as no intermediates with these subunits were detected in the pulse-chase analysis.

-

4.

Almost all of the newly translated Cox3p that cofractionates with Cox1p-HAC (Figure 3, E and G) appears in COX and the supercomplexes after the chase (Figure 3, I and J). This increase does not occur at the expense of any intermediates containing Cox1p-HAC. This suggests that assembly of a Cox3p and perhaps a Cox2p intermediate involves a pathway(s) separate from that of Cox1p.

-

5.

In addition to the regulatory and assembly factors, Cox1p assembly intermediates contain at least two subunits of the enzyme. Both D3 and D4 copurify with Cox5ap-HAC and Cox6p-HAC on protein C antibody beads (Figure 4, E and F). Cox5ap but not Cox6 also appears to be associated with D2. This suggests that the interaction of Cox1p with its immediate partner Cox5ap occurs early during assembly of this module. Both Cox5ap and Cox6p are present in D3, D4, and probably D5. Cox5ap has also been reported to be associated with a Cox1p intermediate that probably corresponds to D3 (Mick et al., 2010). It is not excluded that Cox5ap and Cox6p assemble as a unit, in view of earlier evidence that indicated extensive turnover of Cox5ap in cox6-null mutants and complete release of Cox6p into the matrix in cox5a mutants (Glerum and Tzagoloff, 1997). The absence of Cox1p intermediates in the antibody eluates obtained from strains expressing tagged Cox4p and Cox9p suggests that these subunits may be complexed to other mitochondrially derived subunits during assembly of COX. Cox2p and Cox3p are good candidates, as in the holoenzyme they are in direct contact with Cox9p and Cox4p, respectively, but not with Cox1p (Tsukihara et al., 1996). Because of insufficient exposure to x-ray film, Cox1p and Cox2p are not detectable in the eluate from the strain expressing Cox4p-HAC (Figure 4C), Longer exposures of eluates obtained after pulse-chase labeling of mitochondria from the Cox4p-HAC strain when separated on 2D gels revealed the presence of radiolabeled Cox1p, Cox2p, and Cox3p in the supercomplexes but, as indicated earlier, not in the D1–D5 intermediates (unpublished data). This is supportive of the idea that Cox4p associates after Cox5ap and Cox6p, perhaps as a separate intermediate complexed to Cox3p. The partial adsorption of COX and the supercomplexes in the strain expressing Cox9p-HAC (Figure 4, C and D) indicates that the tag on this subunit is not readily available.

In agreement with previous studies (Pierrel et al., 2007; Perez-Martinez et al., 2009; Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010), biogenesis of Cox1p intermediates is contingent on Mss51p and Cox14p (Figure 6C and Supplemental Figure S4). Inactivation of a temperature-sensitive Mss51p mutant at the restrictive temperature does not interfere with COX biogenesis after translation of Cox1p at the permissive temperature, indicating that the interaction of Cox1p with Mss51p is not obligatorily coupled to translation. Mss51p also associates with D2 but not D1, indicating that the translational activator function of Mss51p is separate from its function as a Cox1p chaperone.

-

6.

Although the sequence of events leading to assembly of COX deduced from the in vitro results reported here could differ in vivo, two lines of evidence argue against it. First is the correspondence in the composition of the major Cox1p intermediate present in mitochondria under steady-state conditions (Pierrel et al., 2007; Fontanesi et al., 2010; Mick et al., 2010) and the D3 intermediate identified by pulse labeling of isolated mitochondria in the present study (point 1 earlier). Second, assembly-dependent regulation of Cox1p translation inferred from in vivo labeling of different cytochrome oxidase mutants (Perez-Martinez et al., 2003, 2009; Barrientos et al., 2004) is also observed when Cox1p-HAC is translated in organello (Supplemental Figure S5).

-

7.

The significance of the observed association of Cox6p-HAC with newly translated Atp9p is not clear. It could signify a coregulation of COX and ATP synthase assembly. It is unlikely that Atp6p plays a role in Atp9p biogenesis, as cox6 mutants are able to assembly ATP synthase efficiently. Recent evidence from studies of mammalian mitochondria suggests that the bc1 and cytochrome oxidase complexes may assemble on a scaffold provided by complex I components (Moreno-Lastres et al., 2012). Because Saccharomyces cerevisiae lacks complex I, this function, if it exists in yeast, might have been acquired by another inner membrane constituent, such as Atp9p.

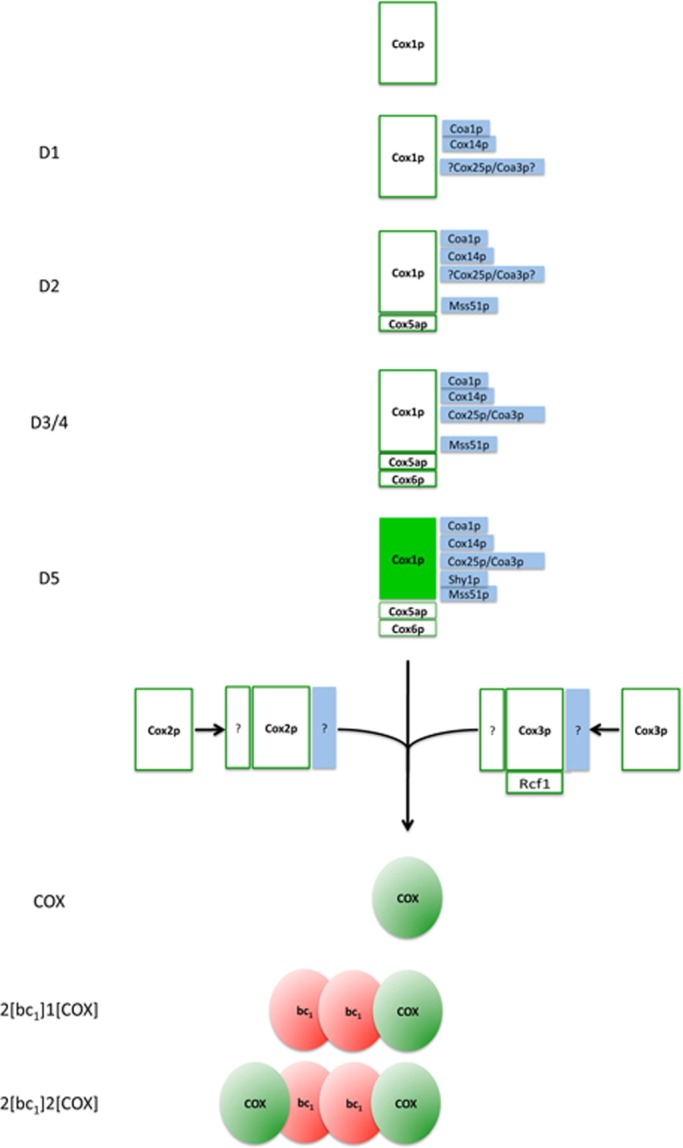

On the basis of these observations, we propose that COX is assembled from possibly three separate modules, as outlined in Figure 7. One consists of Cox1p complexed to Cox5ap and Cox6p. The other modules, Cox2p and Cox3p, might assemble independently with their own complement of subunits. Rcf1p, for example, has been shown to interact with Cox3p and to be required for assembly of this subunit into COX and of the latter into the supercomplex (Strogolova et al., 2012). The sequence in which these modules interact to form the holoenzyme cannot be stated at present. Yeast cox2 mutants have been reported to contain a subassembly consisting of Cox1p and Cox3p (Horan et al., 2005), which could indicate that Cox2p is the last module to enter the assembly pathway.

FIGURE 7:

Scheme of cytochrome oxidase assembly. Newly translated Cox1p interacts with Cox14p and Coa1p to form complex D1. Cox25p/Coa3p was detected in D2, D3, D4, and COX/D5 (unpublished data). Owing to poor labeling of D1, the association of Cox25p/Coa3p with this intermediate is uncertain but is provisionally indicated, mainly because of the similarity of its behavior to that of Cox14p. Mss51p and subunit Cox5ap associate with D1 to form complex D2, which is converted to D3 by addition of Cox6p. D4 migrates separately from complex D3, but the compositional difference between the two is not known. D5, which migrates at the position of COX in the native gel, contains Shy1p in addition to the aforementioned components. D5 is proposed to be the last Cox1p intermediate before it combines with Cox2p and Cox3p, the other two mitochondrially translated subunits that make up the core of the enzyme. The completion of COX biogenesis is followed by its interaction with dimeric bc1 complex. Ssc1p (Fontanesi et al., 2010, 2011) and Coa2 (Pierrel et al., 2008; Bestwick et al., 2010), which have also been implicated in the Cox1p biogenesis pathway, have not been examined and are not shown in this scheme.

Unlike the 11–13 subunits of mitochondrial COX, the bacterial enzyme consists of 3 core subunits (Cox1p, Cox2p, and Cox3p) and in some cases of a fourth polypeptide of unknown function. The temporal order in which the core subunits of bacterial COX interact is likely to have been conserved during the evolutionary process that led to the acquisition of the 8–10 extra subunits. In the model proposed here, the core subunits evolved to form larger units/modules comprising additional proteins without affecting the sequence in which they ultimately assemble into the enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth media

The genotypes and sources of the S. cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table SI. Yeast was grown in either YPD (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose), YPGal (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% galactose) or YEPG (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 3% glycerol, 2% ethanol). Solid media contained 2% agar.

Growth of yeast, isolation of mitochondria, and labeling of mitochondrial gene products

Wild-type and mutant yeast were grown in YPGal to mid–log phase or early stationary phase. Cells were harvested and either used directly to isolate mitochondria or first inoculated into fresh YPGal containing 2 mg/ml chloramphenicol and grown for an additional 2 h. Mitochondria were isolated by the method of Herrmann et al., (1994) after conversion of cells to spheroplasts with Zymolyase 20T. Mitochondrial gene products were labeled in organello with [35S]methionine/cysteine (3000 Ci/mmol; MP Biochemicals, Solon, OH) by the procedure described previously (Rak et al., 2011). The details of individual experiments are included in the legends to the figures.

Construction of COX1-deletion allele

The 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of COX1 were amplified from mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of the strain MR6 with primers COX1-1 and COX1-2, and with COX1-3 and COX1-4 (Supplemental Table S2). The products were digested with combinations of SacI plus BamH1 and BamH1 plus XbaI, respectively. They were ligated to pJM2 (Steele et al., 1996) digested with SacI plus XbaI to obtain pCOX1/ST1 containing the 5′ and 3′ regions of COX1 separated by a BamH1 site. This plasmid was digested with BamH1 and was ligated to a 1.3-kb BamH1 fragment containing ARG8m (Steele et al., 1996). The resultant plasmid (pCOX1/ST2) with the cox1::ARG8m was first introduced into DFKρo (a kar1 mutant lacking mtDNA) by biolistic transformation (Bonnefoy and Fox, 2007), which was subsequently used to substitute the mutant for the wild-type COX1 gene in a strain with an intronless mitochondrial genome (aMRSIo). The resultant respiratory-deficient mutant aMRSIoΔCOX1 was verified genetically to harbor the cox1 null allele.

Construction of COX1-HA, COX1-HApH, and COX1-HAC fusion genes

To construct the fusion gene expressing Cox1p with a C-terminal HA tag, the 5′ and the first exon of COX1 were amplified from MR6 mtDNA with primers COX1-11 and COX1-12. The PCR product was digested with a combination of EcoRI and BamH1 and was substituted for the 5′ UTR of COX1 in pCOX/ST1 (see earlier discussion) to obtain pCOX1/ST7. The remainder of COX1 fused at the 3′ end to a short sequence coding for the HA tag was amplified from the intronless gene of W303Io with primers COX1-13 and COX1-HA. The product was digested with Bsp1286 and BamH1 and was ligated to the PstI and BamH1 sites of pCOX1/ST7. The resultant plasmid pCOX1/ST10 contained the 5′ UTR of MR6, intronless COX1 fused to the sequence coding for the HA tag, followed by ∼500 base pairs of 3′ UTR. This construct was used to obtain genes expressing double-tagged Cox1p. The sequence coding for the polyhistidine tag was added by amplifying the sequence starting from the BstEII site of the gene and ending with the HA tag of pCOX1/ST10 with primers COX1-16 and COX1-HA. The PCR product was digested with a combination of Nco1 and BamH1 and was substituted for the BstEII–BamH1 fragment of pCOX1/ST10 to obtain pCOX1/ST11. Similarly, the protein C tag was added by amplifying the same sequence with primers COX1-16 and COX1-C. The product was digested with BstEII plus BamH1 and substituted for the BstEII–BamH1 fragment of pCOX1/ST10 to obtain pCOX1/ST12.

The kar1 strain DFKρo was transformed by the biolistic method with pCOX1/ST10, pCOX1/ST11, and pCOX1/ST12 containing COX1 fused to the HA, HApH, and HAC tags, respectively. The synthetic ρ− mutants obtained from the transformations were crossed to aMRSIoΔCOX1 to obtain recombinant clones with the HA tag (aMRSIo/COX1-HA), the double HA, polyhistidine tag (MRSIo/COX1-HApH), and the double HA, protein C tag (aMRSIo/COX1-HAC). The COX1 genes were sequenced to confirm the presence of the tags.

Construction of strains expressing nuclear gene products with either C-terminal HAC or CH tags

Genes expressing the double HAC tag were constructed by first amplifying the genes with 5′ primers consisting of 18–21 nucleotides ∼500 base pairs upstream of the initiation codon and a downstream primer with sequences complementary to the HA tag followed by and ending with 18–21 nucleotides of the end of the coding sequence minus the termination codon. The resultant product was ligated to either YIp351 (Hill et al., 1986) or YIp349 (identical to YIp351, except that the LEU2-selectable marker was replaced with a 1-kb fragment of DNA containing TRP1). The resultant plasmid was used as an amplification template with the same 5′ primer and a 3′ primer consisting of a sequence complementary to the protein C tag followed by two glycine codons and ending with 21 nucleotides of a sequence complementary to the HA tag. The PCR products were ligated into the same integrative plasmids, which were linearized at the LEU2 or TRP1 gene for homologous recombination (Rothstein, 1983) of the corresponding pet-null mutant. The sequences of the primers for these constructs are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Hybrid genes expressing proteins with C-terminal double-CH tags (protein C followed by polyhistidine) were amplified with 5′ primers containing 18–21 nucleotides of a sequence ∼500 base pairs upstream of the initiation codon and a 3′ primer complementary to 18–21 nucleotides of the end of the gene minus the termination codon. The amplified products were cloned into either YIp351-CH or YIp352-CH, which were linearized at the LEU2 or URA3 gene, respectively, and integrated at homologous locus of the corresponding null mutants. YIp351-CH and YIp352-CH were constructed by ligating into the PstI and HindIII sites of these plasmids a double-stranded oligonucleotide with the sequence coding for the protein C tag, followed by three glycine codons and ending with six histidine codons. The sequences of the primers used for the gene amplifications and of the double-stranded oligonucleotide to obtain the modified plasmids are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Miscellaneous procedures

Preparation and ligation of DNA and transformation of Escherichia coli were done by standard methods (Sambrook et al., 1989). Yeast was transformed by the lithium acetate method of Schiestl and Gietz (1989). Proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE on different concentrations of polyacrylamide gels in the buffer system of Laemmli (1970) and by BN-PAGE on 4–13% polyacrylamide gels as described (Wittig et al., 2006). Second-dimension SDS–PAGE was run on 12% polyacrylamide gels. Western blots were treated with antibodies against the appropriate proteins, followed by a second reaction with anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Proteins were detected with SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein concentrations were estimated by the Lowry procedure (Lowry et al., 1951).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant GM50187.

Abbreviations used:

- BN-PAGE

blue native PAGE

- COX

cytochrome oxidase

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- Ni-NTA

nickel nitriloacetic acid

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- UTR

untranslated region

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0749) on December 24, 2012.

REFERENCES

- Barrientos A, Zambrano A, Tzagoloff A. Mss51p and Cox14p jointly regulate mitochondrial Cox1p expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 2004;23:3472–3482. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bestwick MM, Jeong Y, Khalimonchuk O, Kim Y, Winge DR. Analysis of Leigh syndrome mutations in the yeast SURF1 homolog reveals a new member of the cytochrome oxidase assembly factor family. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4480–4491. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00228-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnefoy N, Fox TD. Directed alteration of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondrial DNA by biolistic transformation and homologous recombination. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;372:153–166. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-365-3_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr HS, Winge DR. Assembly of cytochrome c oxidase within the mitochondrion. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:309–316. doi: 10.1021/ar0200807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choquet Y, Wostrikoff K, Rimbault B, Zito F, Girard-Bascou J, Drapier D, Wollman FA. Assembly-controlled regulation of chloroplast gene translation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:421–426. doi: 10.1042/bst0290421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobine PA, Pierrel F, Winge DR. Copper trafficking to the mitochondrion and assembly of copper metalloenzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieckmann C L, Tzagoloff A. Assembly of the mitochondrial membrane system. CBP6, a yeast nuclear gene necessary for synthesis of cytochrome b. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:1513–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanesi F, Clemente P, Barrientos A. Cox25 teams up with Mss51, Ssc1, and Cox14 to regulate mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 expression and assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:555–566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.188805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanesi F, Soto IC, Horn D, Barrientos A. Mss51 and Ssc1 facilitate translational regulation of cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:245–259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00983-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glerum DM, Tzagoloff A. Submitochondrial distributions and stabilities of subunits 4, 5, and 6 of yeast cytochrome oxidase in assembly defective mutants. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:410–414. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00799-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannappel AF, Bundschuh A, Ludwig B. Role of Surf1 in heme recruitment for bacterial COX biogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:928–937. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer J, Braun HP, Boekema EJ, Kouril R. A structural model of the cytochrome c reductase/oxidase supercomplex from yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12240–12248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610545200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann JM, Foelsch H, Neupert W, Stuart RA. Isolation of yeast mitochondria and study of mitochondrial protein translation. In: Celis JE, editor. In: Cell Biology: A Laboratory Handbook. Vol. I. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JE, Myers AM, Koerner TJ, Tzagoloff A. Yeast/E. coli shuttle vectors with multiple unique restriction sites. Yeast. 1986;2:163–167. doi: 10.1002/yea.320020304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan S, Bourges I, Taanman JW, Meunier B. Analysis of COX2 mutants reveals cytochrome oxidase subassemblies in yeast. Biochem J. 2005;390:703–708. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalimonchuk O, Bestwick M, Meunier B, Watts TC, Winge DR. Formation of the redox cofactor centers during Cox1 maturation in yeast cytochrome oxidase. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1004–1017. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00640-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Khalimonchuk O, Smith PM, Winge DR. Structure, function, and assembly of heme centers in mitochondrial respiratory complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1604–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick DU, Fox TD, Rehling P. Inventory control: cytochrome c oxidase assembly regulates mitochondrial translation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:14–20. doi: 10.1038/nrm3029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick DU, Vukotic M, Piechura H, Meyer HE, Warscheid B, Deckers M, Rehling P. Coa3 and Cox14 are essential for negative feedback regulation of COX1 translation in mitochondria. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:141–154. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mick DU, Wagner K, van der Laan M, Frazier AE, Perschil I, Pawlas M, Meyer HE, Warscheid B, Rehling P. Shy1 couples Cox1 translational regulation to cytochrome c oxidase assembly. EMBO J. 2007;26:4347–4358. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileykovskaya E, Penczek PA, Fang J, Mallampalli VK, Sparagna GC, Dowhan D. Arrangement of the respiratory chain complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae supercomplex III2IV2 revealed by single particle cryo-electron microscopy. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23095–23103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.367888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Lastres D, Fontanesi F, García-Consuegra I, Martín MA, Arenas J, Barrientos A, Ugalde C. Mitochondrial complex I plays an essential role in human respirasome assembly. Cell Metab. 2012;15:324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Martinez X, Broadley SA, Fox TD. Mss51p promotes mitochondrial Cox1p synthesis and interacts with newly synthesized Cox1p. EMBO J. 2003;22:5951–5961. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Martinez X, Butler CA, Shingu-Vazquez M, Fox TD. Dual functions of Mss51 couple synthesis of Cox1 to assembly of cytochrome c oxidase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4371–4380. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-06-0522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrel F, Bestwick ML, Cobine PA, Khalimonchuk O, Cricco JA, Winge DR. Coa1 links the Mss51 post-translational function to Cox1 cofactor insertion in cytochrome c oxidase assembly. EMBO J. 2007;26:4335–4346. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrel F, Khalimonchuk O, Cobine PA, Bestwick M, Winge DR. Coa2 is an assembly factor for yeast cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis that facilitates the maturation of Cox1. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4927–4939. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00057-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rak M, Gokova S, Tzagoloff A. Modular assembly of yeast mitochondrial ATP synthase. EMBO J. 2011;30:920–930. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein RJ. One-step gene disruption in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:202–211. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schiestl RH, Gietz RD. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto IC, Fontanesi F, Liu J, Barrientos A. Biogenesis and assembly of eukaryotic cytochrome c oxidase catalytic core. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:883–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele DF, Butler CA, Fox TD. Expression of a recoded nuclear gene inserted into yeast mitochondrial DNA is limited by mRNA-specific translational activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5253–5257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strogolova V, Furness A, Robb-McGrath M, Garlich J, Stuart RA. Rcf1 and Rcf2, members of the hypoxia-induced gene 1 protein family, are critical components of the mitochondrial cytochrome bc1-cytochrome c oxidase supercomplex. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1363–1373. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06369-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukihara T, Aoyama H, Yamashita E, Tomizaki T, Yamaguchi H, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Nakashima R, Yaono R, Yoshikawa S. The whole structure of the 13-subunit oxidized cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A. Science. 1996;272:1136–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5265.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzagoloff A, Barrientos A, Neupert W, Herrmann JM. Atp10p assists assembly of Atp6p into the F0 unit of the yeast mitochondrial ATPase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19775–19780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig I, Braun HP, Schagger H. Blue native PAGE. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:418–428. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Barros MH, Shulman T, Tzagoloff A. ATP25, a new nuclear gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae required for expression and assembly of the Atp9p subunit of mitochondrial ATPase. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:1366–1377. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-08-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.