Abstract

Purpose

Global data on human papillomavirus serological and DNA prevalence are essential to optimize HPV prophylactic vaccination strategies.

Methods

We conducted a global review of age-specific HPV antibody and studies with both antibody and DNA prevalence for HPV types 16, 18, 6 and 11.

Results

One hundred-seventeen studies were included; participants’ ages ranged from several hours to over 90 years. HPV 16 seroprevalence was generally higher in Africa, Central and South America, and North America, more prevalent among women than men, and peaked around ages 25-40 years. HPV 18 seroprevalence was generally lower than HPV 16 with a later age peak. Data were limited for HPV 6 and 11, which both peaked at ages similar to HPV 18. In 9-26 year-old females, HPV 16 seroprevalence ranged from 0-31% in North America, 21-30% in Africa, 0-23% in Asia/Australia, 0-33% in Europe, and 13-43% in Central and South America. HPV 16/18 DNA prevalence peaked 10-15 years before corresponding HPV 16/18 antibody prevalence.

Conclusions

Females within the HPV-vaccine eligible age group (9-26 years) had a range of dual HPV 16 DNA and serology negativity from 81-87%, whereas 90-98% were HPV 16 DNA negative. Serology and DNA data are lacking worldwide for females younger than age 15 years, the prime target group for vaccination.

Keywords: Global, Human papillomavirus, Serology, DNA, prevalence, immunology, antibodies

Introduction

Persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is necessary for the development of invasive cervical cancer, the second most common cancer in women worldwide (1,2). Two vaccines are now available against the most common oncogenic types, HPV 16 and 18 (3). Knowledge of the epidemiology of vaccine type-specific HPV exposure could inform strategies for optimal implementation of these prophylactic, but not therapeutic, vaccines (3-6). DNA status and serological responses are commonly used indexes to assess HPV exposure (7,8). HPV DNA status provides direct evidence of current viral infection, but since most HPV infections are cleared within 6-12 months (9), it cannot reliably measure cumulative HPV exposure on its own. Type-specific serological HPV antibody responses are better indicators of the history of HPV exposure (7), although not all HPV infections lead to seroconversion (10), so serology data alone will underestimate cumulative HPV exposure (11). However, persistent HPV infections are more likely to cause seroconversion than transient infections (10,12) putting women at greater risk for high-grade cervical neoplasia and cervical cancer (13). Thus, serological data may provide information on women at a higher risk for clinically important disease. Although neither HPV DNA nor serology data should be used alone when estimating cumulative HPV exposure, these data together combined with information on age of first intercourse would be beneficial for designing effective HPV vaccination programs.

To our knowledge, no previous review has been conducted on age-specific HPV seroprevalence worldwide, or on studies with both HPV DNA and seroprevalence data. As exposure to the HPV virus varies notably by geographic location and age (14), these variables are important to consider when interpreting results. In this global review, we compiled and classified age-specific data from cross-sectional studies conducted in non-high-risk populations. Data are presented on the seroprevalence of HPV 16, 18, 6, and 11 as well as on HPV DNA and serology data available within the same population.

Methods

Material reviewed

We conducted a global review by searching Medline for articles published through September 2010. To identify published papers on HPV serology, we used the following search terms: ‘human papillomavirus, human, serology, serologic tests, antibodies, and immunology’. For papers with HPV DNA and serology within the same population, we used the same search terms plus ‘DNA’. References cited in identified articles were also reviewed. Eligible studies were restricted to peer-reviewed articles with cross-sectional data on serological prevalence of antibodies to the L1 or L1/L2 capsid proteins or capsomeres of HPV types 16, 18, 6 or 11, and studies with both seroprevalence data and data on cross-sectional prevalence of HPV 16, 18, 6 or 11 DNA. Any other type of serological assay was excluded, including assays for antibodies against E (early) proteins, L2 proteins alone, and Western blot testing. Studies presenting data on IgA and/or IgM only were excluded. Studies were confined to non-HPV vaccinated, non-high-risk populations (e.g. not HIV-positive, immuno-compromised, sex workers, or attending STD clinics), and included population-based samples or control patients of case-control studies. Required sample sizes were at least 50 people per study and greater than 15 people per age group. When necessary, age groups were combined. Studies without age-specific data (mean or median age, age range, or data stratified by age groups) were excluded, as were conference abstracts and unpublished manuscripts.

Data extraction

For each included study, the following data were extracted if applicable: first author, publication year, date and location of sample collection, population gender, age, and common characteristics (for example, the type of clinic from which they were recruited), sample size, serologic and DNA assay type, PCR primers used, HPV types detected, and age-specific data on prevalence of HPV serology responses and HPV DNA prevalence for HPV types 16, 18, 6, and 11. Overall mean age and prevalence data of HPV DNA and serum antibody responses were reported if age-specific data were not available. All HPV DNA and serology data were abstracted directly from published tables if available, otherwise they were estimated from published graphs using enlarged images and a ruler. For studies that presented identical data for the same population in multiple publications, the publication with the largest sample size was chosen. For quality control, data were double-extracted by two independent researchers and any discordant results were resolved by consensus. Within each geographic area, studies were ordered alphabetically by country and city/region within the country (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. HPV 16, 18, 6, and 11 seroprevalence estimates, stratified by continent, country and study year.

| Study location, dates, reference |

Assay | Group Tested | Sex | Mean or median age, years (range) or ± SD |

Sample size | Seroprevalence (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV 16 | HPV 18 | HPV 6 | HPV 11 | ||||||

| Africa | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Mali, near Bamako 1994-1995 (15) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 47 (18-80) | 97 | 36.1 | 7.2 | ||

| Nigeria, Ibadan 1997-2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population-based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 922 | 27.1 | 24.8 | ||

| 15-24 | 119 | 24.4 | 21.9 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 188 | 25.5 | 27.1 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 131 | 26.7 | 24.4 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 196 | 28.1 | 23.5 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 288 | 28.8 | 25.7 | ||||||

| South Africa, Cape Town 1994-97 (17,20) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Blood donors | M+F | 1-2 | 25 | 24.0 | |||

| 3-4 | 31 | 12.9 | |||||||

| 5-6 | 24 | 29.2 | |||||||

| 7-8 | 27 | 7.4 | |||||||

| 9-10 | 28 | 21.4 | |||||||

| 11-12 | 20 | 30.0 | |||||||

| F | 37 (21->50) | 95 | 25.3 | 10.5 | |||||

| 21-30 | 24 | 20.8 | |||||||

| 31-40 | 45 | 15.6 | |||||||

| 41->50 | 26 | 7.7 | |||||||

| South Africa, near Cape Town (2008) (19) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 44 (18-59) | 908 | 44.1 | |||

| 18-29 | 60.0 | ||||||||

| 30-34 | 40.5 | ||||||||

| 35-39 | 51.6 | ||||||||

| 40-44 | 50.3 | ||||||||

| 45-49 | 41.5 | ||||||||

| 50-54 | 36.2 | ||||||||

| 55-59 | 34.2 | ||||||||

| South Africa, Johannesburg 1999 (21) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Mothers from paternity dispute clinic |

F | 31 (16-45) | 100 | 17.0 | 16.0 | 21 | |

| Children from paternity dispute clinic |

M+F | 3.75 (0.33-20) | 111 | 9.0 | 9.9 | 11.7 | |||

| <2 | 37 | 5.4 | 10.8 | 13.5 | |||||

| 2-10 | 55 | 7.3 | 10.9 | 9.1 | |||||

| 11-20 | 19 | 21.0 | 5.3 | 15.8 | |||||

| South Africa, Schmidtsdrift 1993 (18) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Baseline epidemiology study for immunization program among San people |

M+F | 2-7 | 46 | 10.9 | 6.5 | ||

| 8-12 | 69 | 2.9 | 7.2 | ||||||

| 13-19 | 17 | 11.8 | 11.8 | ||||||

| 20-35 | 51 | 13.7 | 15.7 | ||||||

| 36-83 | 50 | 18.0 | 22.0 | ||||||

| M | 7.6 (2-12) | 54 | 9.3 | 9.3 | |||||

| F | 8.3 (2-12) | 61 | 3.3 | 3.3 | |||||

| F | 38 (20-83) | 101 | 15.8 | 18.8 | |||||

| Tunisia, La Rabta, Tunis (2009) (22,23) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 46 (26-65) | 70 | 3.0 | 17.0 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Asia and Australia | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| China, Gansu 2007- 2008 (34) |

GFP- pseudovirus- L1/L2 based neutralization assay |

Women with genital diseases not related to cervical cancer |

F | 38.9± 9.9 | 50 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0 |

| China, Hunan 1984- 1988 (24) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, penile cancer study |

M | 55 (20-74) | 60 | 0.0 | |||

| China, Linxian 1985-1991 (27) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, gastric and esophageal cancer study |

M+F | 55 (40-69) | 381 | 7.6 | 9.2 | ||

| India, 4 different sites, 2006-2007 (38) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 28.4 (18-35) | 312 | 12.5 | 19.6 | ||

| Japan, n/s (1997) (25) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Controls for condyloma patients |

F | 25.4 (16-32) | 48 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 25 | |

| Controls for CIN patients |

F | 43.2 (25-60) | 98 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 24 | |||

| Controls for cervical cancer patients |

F | 53.7 (35-85) | 102 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 19 | |||

| Japan, n/s 2006 (37) | Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 22.5 (20-25) | 1040 | 17.3 | 15.8 | ||

| Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar 2005 (29) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population- based sample |

F | 15-59 | 969 | 23.0 | 19.6 | ||

| 15-34 | 449 | 19.0 | 15.0 | ||||||

| 35-59 | 520 | 22.5 | 22.5 | ||||||

| 15-24 | 196 | 28.5 | |||||||

| 25-29 | 129 | 25.0 | |||||||

| 30-34 | 124 | 25.5 | |||||||

| 35-39 | 133 | 34.0 | |||||||

| 40-44 | 123 | 28.0 | |||||||

| 45-49 | 127 | 30.0 | |||||||

| 50-59 | 137 | 33.0 | |||||||

| South Korea, Ansan 2003-2006 (32,33) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 43 (24-69) | 106 | 20.8 | 12.3 | ||

| South Korea, Busan 1997-2000 (16,26) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (20-74) | 860 | 5.9 | 9.0 | ||

| 15-34 | 155 | 6.4 | 6.4 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 278 | 6.5 | 10.1 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 233 | 6.4 | 11.6 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 194 | 4.1 | 6.2 | ||||||

| South Korea, Busan 2002 (28) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

University students |

F/M | 15-29 | 817/518 | 4.9/2.5 | 5.5/5.2 | ||

| South Korea, n/s 2005-2006 (30) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 16.6 (9-23) | 117 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.9 | |

| Taiwan, n/s 1991- 1995 (36) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 47.8 (30-64) | 519 | 8.1 | 14.8 | 31.0 | |

| Taiwan, Taipei, Taichung and Kaohsiung 1999 (35) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Age and gender- stratified sampling from general population |

F/M | <1 | 119/119 | 0.0/0.8 | 0.0/0.0 | ||

| 1-12 | 117/121 | 2.0/0.0 | 1.0/2.0 | ||||||

| 13-15 | 91/84 | 1.5/1.0 | 2.5/0.0 | ||||||

| 16-18 | 52/85 | 0.0/1.0 | 2.4/1.0 | ||||||

| 19-25 | 107/42 | 6.5/0.0 | 3.0/0.0 | ||||||

| 26-30 | 122/38 | 7.4/7.6 | 3.7/5.0 | ||||||

| 31-40 | 159/91 | 12/5.2 | 5.2/3.2 | ||||||

| 41-50 | 85/42 | 11.8/2.5 | 5.4/2.5 | ||||||

| 51-60 | 77/24 | 21/8.3 | 9.0/4.2 | ||||||

| 61-86 | 71/56 | 16.8/23.0 | 8.4/16.0 | ||||||

| Taiwan, Taipei 2004 (31) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Students | F | 10-22 | 826 | 1.6 | |||

| 10 | 287 | 0.3 | |||||||

| 13 | 235 | 0.9 | |||||||

| 16 | 185 | 3.2 | |||||||

| 19-22 | 119 | 3.4 | |||||||

| Thailand, Lampang 1997-2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 1018 | 15.1 | 12.2 | ||

| 15-24 | 129 | 13.2 | 5.4 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 179 | 11.2 | 10.6 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 176 | 21.0 | 14.8 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 167 | 19.2 | 13.8 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 367 | 13.1 | 13.4 | ||||||

| Thailand, Songkla 1997-2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 704 | 2.7 | 2.7 | ||

| 15-24 | 69 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 112 | 2.7 | 2.7 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 122 | 4.1 | 4.1 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 129 | 4.7 | 3.1 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 272 | 1.8 | 1.1 | ||||||

| Vietnam, Hanoi 1997-2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population -based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 957 | 0.6 | 0.2 | ||

| 15-24 | 121 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 178 | 1.7 | 0.6 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 176 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 157 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 325 | 0.3 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City 1997- 2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 803 | 20.9 | 11.6 | ||

| 15-24 | 128 | 12.5 | 14.1 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 154 | 22.7 | 13.0 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 163 | 24.5 | 6.8 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 136 | 21.3 | 11.8 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 222 | 21.6 | 12.6 | ||||||

| Australia, New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland 2005 (39) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population -based sample |

F/M | 0-69 | 1523/1247 | 12.4/7.9 | 5.7/3.9 | 12.9/9.1 | 5.2/5.2 |

| 0-9 | 128/148 | 0/0.0 | 0/0.0 | 0/0.0 | 0/0.0 | ||||

| 10-14 | 95/119 | 2.1/0.0 | 0/0.0 | 1.1/0.0 | 1.1/0.0 | ||||

| 15-19 | 142/165 | 7/0.6 | 4.9/0.6 | 7/0.6 | 1.4/1.2 | ||||

| 20-29 | 247/209 | 14.6/7.2 | 6.1/1.9 | 15/9.6 | 4.5/7.2 | ||||

| 30-39 | 313/172 | 22/12.2 | 10.5/5.2 | 22/15.1 | 6.4/7.6 | ||||

| 40-49 | 288/143 | 19.8/14.0 | 7.6/7.7 | 18.8/15.4 | 11.8/9.1 | ||||

| 50-59 | 158/147 | 13.3/14.3 | 7/8.2 | 17.7/12.9 | 4.4/7.5 | ||||

| 60-69 | 152/144 | 8.6/6.3 | 4.6/4.2 | 9.9/10.4 | 7.2/2.8 | ||||

| Australia, Brisbane and Townsville (2009) (40) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Randomly selected controls, skin cancer study |

F+M | 70 (31-91) | 276 | 11.2 | 24.0 | ||

| Multi-country (Australia, Hong Kong, Israel, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand) 2000- 2007 (41) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 21 (16-26) | 860 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.7 |

|

| |||||||||

| Europe | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Austria, Innsbruck 1991-1992 (42) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 31.4 (16-51) | 87 | 11.5 | |||

| Randomly chosen pregnant women at time of delivery |

F | 27.8 (17-40) | 63 | 15.9 | |||||

| Austria, Innsbruck 1991-1994 (45) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 31 (16-81) | 126 | 14.3 | 10.3 | ||

| Austria, n/s 1987- 1998 (43) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 35 (22-67) | 102 | 14.0 | 8.0 | ||

| Austria, n/s (2003) (44) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study and convenience sample submitted for diagnostic tests |

M | 42.5 (n/s) | 198 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 10.2 | 5.1 |

| Czech Republic n/s 1993-1995 (72) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F+M | 0-5 | 50 | 2.0 | 3.0 | ||

| 6-12 | 50 | 2.0 | 3.0 | ||||||

| 13-20 | 59 | 7.0 | 5.0 | ||||||

| 21-25 | 49 | 11.0 | 9.0 | ||||||

| 26-30 | 50 | 9.0 | 7.0 | ||||||

| 31-35 | 42 | 22.0 | 9.0 | ||||||

| 36-45 | 50 | 19.0 | 11.0 | ||||||

| 46-60 | 50 | 19.0 | 13.0 | ||||||

| >60 | 50 | 23.0 | 21.0 | ||||||

| Czech Republic, n/s (1999) (73) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 32.4 (20-77) | 89 | 14.6 | 14.6 | ||

| 20-30 | 62 | 9.7 | 11.3 | ||||||

| 31-77 | 27 | 25.9 | 22.2 | ||||||

| Czech Republic, Prague 2000-2004 (74) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, head and neck cancer study Blood donor |

F+M | 54.3 (n/s) | 111 | 14.4 | |||

| Finland, n/s (2001) (46) |

Direct binding VLP-based ELISA |

controls, laryngeal papillomatosis study |

F+M | 51 (26-77) | 53 | 23.0 | 21 | 15 | |

| Finland, National 1983-1997 (47) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Finnish Maternity Cohort 1983-97 |

F | 24 (14-31) | 7085 | 18.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | |

| 14-19 | 1239 | 16.0 | 9.0 | 10.0 | |||||

| 20-22 | 1308 | 20.0 | 10.0 | 11.0 | |||||

| 23-25 | 2130 | 19.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | |||||

| 26-28 | 2060 | 19.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | |||||

| 29-31 | 1068 | 16.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | |||||

| Finland, National 1983-2003 (48) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Finnish Maternity Cohort 1983-97 |

F | <32 | 7815 | 18.3 | 10.2 | 7.6 | |

| Finnish Maternity Cohort 1995-03 |

F | <29 | 3252 | 19.5 | 14.1 | 9.9 | |||

| Finland, National 1968-1991 (49) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based serum samples from National registry |

M | 58.3 (18-78) | 290 | 1.7 | 4.5 | 8.7 | |

| Finland, National 1966-1972 (50) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based serum samples from National registry |

F | 39.1 (15-83) | 143 | 2.1 | |||

| Finland, Turku 1998-2001 (51) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV study |

F | 25.5 (18-38) | 290 | 34.9 | 21.5 | 53.3 | 21.5 |

| Germany, National 1985-1989, 1991- 1992, 2002 (54) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population based sample |

F/M | 1-14 | 95/92 | 0/1.0 | 1/2.0 | ||

| 15-24 | 143/92 | 7.7/3.0 | 4.6/1.0 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 223/154 | 14.5/1.2 | 6/3.3 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 165/113 | 9.9/6.0 | 6.2/2.7 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 171/111 | 11.8/4.8 | 3.5/5.3 | ||||||

| 55-64 | 149/115 | 11.6/2.6 | 3.7/3.8 | ||||||

| Germany, n/s (1996) (52) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Male Fertility patient controls for genital wart study |

M | 35.6 (17-73) | 124 | 3.2 | |||

| Blood donor controls, genital wart study |

F+M | 41.5 (22-65) | 88 | 18.2 | |||||

| Hospital/clinic- based controls, genital wart study |

F+M | 38.5 (22-60) | 92 | 3.5 | |||||

| Germany, Heidelberg 1991- 1992 (53) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Children attending hospital/clinic for HPV unrelated reasons |

F+M | 4.7 (1-10) | 66 | 1.5 | |||

| Italy, Rome (2008) (55) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, skin cancer study |

F+M | 72 (n/s) | 77 | 18.2 | 13.0 | ||

| Italy, Rome (2009) (40) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, skin cancer study |

F+M | 66 (27-96) | 256 | 12.0 | 42.0 | ||

| The Netherlands, n/s 1985-1989 (56) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Controls, penile cancer study |

M | 64 (27-81) | 83 | 2.4 | 4.8 | ||

| The Netherlands, Amsterdam 1991- 1996 (10) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, skin cancer study |

F | 35.6 ± 10.2 | 50 | 2.0 | |||

| The Netherlands, Leiden (2009) (40) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Hospital/clinic- based controls, skin cancer study |

F+M | 64 (38-80) | 275 | 11.0 | 35.0 | ||

| Norway, Oslo 1991- 1992 (57) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population based control, cervical cancer study |

F | 32.8 (20-44) | 234 | 16.7 | |||

| F | 20-24 | 15 | 33.3 | ||||||

| 25-29 | 69 | 8.7 | |||||||

| 30-34 | 71 | 21.1 | |||||||

| 35-39 | 50 | 16.0 | |||||||

| 40-44 | 29 | 17.2 | |||||||

| Norway, Oslo, Trondheim, Levanger 1998- 2000 (58) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Hospital/clinic based healthy subjects |

F | 21.2 (16-24) | 896 | 16.2 | 6.4 | 12.7 | 2.6 |

| 16-20 | 382 | 13.4 | 5.5 | 10.8 | |||||

| 21-24 | 514 | 18.3 | 7.0 | 14.2 | |||||

| Spain, Barcelona 1997-2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (>15) 15-24 |

908 160 |

0.8 1.9 |

3.1 3.8 |

||

| 25-34 | 158 | 1.3 | 3.8 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 173 | 0.6 | 1.2 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 160 | 0 | 2.5 | ||||||

| ≥55 | 257 | 0.4 | 3.9 | ||||||

| Spain, Oviedo, Barcelona (2001) (59) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls, HPV study |

F | 30.3 (19-49) | 283 | 6.0 | 1.8 | ||

| Sweden, Karlstad 1989-1990 (61) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Urban high school students |

F | 16.1(15-17) | 98 | 3.1 | |||

| Sweden, National 1997 and 2004- 2008 (67) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

National serologic survey |

F+M | 9-26 | 1163 | 3.5 | |||

| Southern Sweden serologic survey |

F+M | 11-25 | 2154 | 3.1 | |||||

| Patients attending primary care clinics in Sweden |

F/M | 9-26 | 1816/ 1501 |

4.5/1.8 | |||||

| F/M | 9 | 107/118 | 0/0.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 11 | 172/198 | 0/0.5 | ||||||

| F/M | 12 | 66/83 | 1.5/0.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 13 | 106/81 | 0/2.5 | ||||||

| F/M | 14 | 122/103 | 0.8/1.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 15 | 299/237 | 2.3/1.3 | ||||||

| F/M | 16 | 181/135 | 1.7/0.7 | ||||||

| F/M | 17 | 145/114 | 4.1/0.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 18 | 249/160 | 6.8/3.8 | ||||||

| F/M | 19 | 91/63 | 11.0/0.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 20-22 | 132/106 | 9.8/5.7 | ||||||

| F/M | 23-26 | 146/103 | 15.8/6.8 | ||||||

| Sweden, Orebro County 1989-1991 (68) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls of prostate cancer study |

M | 69.9 | 210 | 15.2 | 11.9 | ||

| Sweden, Stockholm and Eskilstuna 1996 (63) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Family planning or youth clinic patients |

F | 26 (16-48) | 274 | 21.1 | 16.0 | 12.4 | |

| Sweden, Stockholm, 1989- 1992 (64) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Blood donor controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 48 (28-80) | 243 | 17.7 | 20.1 | ||

| Sweden, Stockholm (1999) (65) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Children, blood samples taken for reasons unrelated to HPV infection |

F+M | 0-13 | 1031 | 3.0 | 0.6 | ||

| 0-0.5 | 58 | 5.2 | 5.2 | ||||||

| >0.5-1.5 | 190 | 2.1 | 0.0 | ||||||

| >1.5-3 | 181 | 2.8 | 0.6 | ||||||

| >3-5 | 177 | 0.6 | 0.0 | ||||||

| >5-7 | 136 | 2.9 | 0.0 | ||||||

| >7-10 | 165 | 6.1 | 1.2 | ||||||

| >10-13 | 124 | 3.2 | 0.0 | ||||||

| Sweden, Stockholm 1989-1992 (69) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Blood donor controls, anal cancer study |

F+M | 60 | 79 | 9.0 | 32 | ||

| Sweden, Umea 1986-1991 (60) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 48.8 (18-64) | 188 | 10.0 | 30.0 | ||

| Sweden, Vasterbotten 1987- 1993 (62) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 40 (29-61) | 148 | 16.0 | 15.0 | ||

| 29-34 | 46 | 11.0 | |||||||

| 35-44 | 72 | 17.0 | |||||||

| 45-61 | 30 | 23.0 | |||||||

| Sweden, Vasterbotten 1993- 1995 (66) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based women with normal cytology, cervical cancer study |

F | 39.1 (15-83) | 348 | 26.0 | |||

| UK, England, n/s, 2002-2004 (71) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

National convenience sample submitted for diagnostic tests |

F | 10-29 | 1483 | 11.9 | 4.7 | 10.7 | |

| F | 10 | 90 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 11 | 90 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 12 | 90 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 13 | 90 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 14 | 90 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 15 | 90 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 0 | |||

| F | 16 | 90 | 8.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 1 | |||

| F | 17 | 90 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 8.0 | 3 | |||

| F | 18 | 90 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 12.0 | 2 | |||

| F | 19 | 90 | 12.0 | 4.0 | 13.0 | 1 | |||

| F | 20 | 60 | 14.0 | 2.0 | 15.0 | 4 | |||

| F | 21 | 60 | 19.0 | 5.0 | 18.0 | 8 | |||

| F | 22 | 60 | 29.0 | 11.0 | 19.0 | 5 | |||

| F | 23 | 60 | 22.0 | 10.0 | 24.0 | 4 | |||

| F | 24 | 60 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 19.0 | 7 | |||

| F | 25 | 60 | 17.0 | 6.0 | 12.0 | 8 | |||

| F | 26 | 60 | 22.0 | 10.0 | 13.0 | 4 | |||

| F | 27 | 60 | 28.0 | 7.0 | 13.0 | 3 | |||

| F | 28 | 60 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 7 | |||

| F | 29 | 60 | 20.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 3 | |||

| UK, Scotland, Edinburgh 1994- 1995 (70) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

School girls participating in rubella vaccination program |

F | 11-13 | 1192 | 14.8 | |||

| Multi-country across Europe, 2004-2006 (75) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 35 (15-55) | 666 | 22.2 | 11.3 | ||

| 15-25 | 224 | 12.9 | 7.1 | ||||||

| 26-45 | 226 | 24.3 | 14.2 | ||||||

| 46-55 | 211 | 30.3 | 12.8 | ||||||

| 17 sites across Europe: Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, The Netherlands, Russia, 2004-2005 (76) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 12.4 (10-14) | 158 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 20.2 (15-25) | 458 | 16 | 15 | ||||||

| Multi-country, 35 sites across France, Spain, Germany, 2007-2008 (83) Multi-country, (Czech Republic, |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 14 (10-18) | 751 | 7.5 | 7.1 | ||

| Denmark, England, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal Spain, and Sweden) 2000-2007 (41) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population- based sample |

F | 19.7 (16-24) | 9333 | 10.2 | 3.7 | 7.4 | 1.5 |

|

| |||||||||

| North America | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Canada, British Columbia, 2007- 2008 (78) |

GFP- pseudovirus- L1/L2 based neutralization assay |

Women undergoing prenatal testing |

F | 15-39 | 1020 | 17.9 | 9.5 | ||

| 15-19 | 340 | 19 | 6 | ||||||

| 20-24 | 123 | 21 | 9 | ||||||

| 25-29 | 217 | 20 | 8 | ||||||

| 30-34 | 203 | 15 | 10 | ||||||

| 35-39 | 137 | 11 | 10.9 | ||||||

| Canada, Montreal 1997-2001 (79) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, oral cancer study |

F+M | 25-84 | 128 | 3.9 | |||

| Jamaica, Kingston 1987-1988 (80) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Blood donors | F | 27.3 (17-59) | 116 | 24.0 | |||

| M | 30.4 (17-80) | 141 | 19.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 17-19 | n/s | 9/0.0 | ||||||

| 20-24 | n/s | 18/13.0 | |||||||

| 25-29 | n/s | 32/19.5 | |||||||

| 30-34 | n/s | 41/28.0 | |||||||

| 35-80 | n/s | 20/29.5 | |||||||

| Jamaica, Kingston 1989-1990 (81) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

HTLV and HIV-1 negative mother-infant pairs from HTLV study, |

F | 26 (15-44) | 98 | 23.5 | |||

| F+M | 1.8 (1.3-2.2) | 98 | 3.1 | ||||||

| US, Tuscon, AZ, Tampa, FL 2003- 2005 (95) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based study |

M | 18-40 | 462 | 12.1 | 5.4 | 9.7 | |

| 18-24 | n/s | 5.7 | 1 | ||||||

| 25-29 | n/s | 5.6 | 2 | ||||||

| 30-34 | n/s | 16.0 | 1.5 | ||||||

| 35-40 | n/s | 35.4 | 25.0 | ||||||

| US, Tucson, Arizona, 2003-2005 (99) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

M | 29.8 (18-44) | 285 | 14.8 | 21.1 | ||

| 18-25 | 113 | 13.3 | |||||||

| 26-35 | 86 | 19.8 | |||||||

| 36-44 | 86 | 58.1 | |||||||

| US, Oakland, California, 1959- 1993 (107) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Controls from Child Health and Development cohort, prostate cancer study |

M | 36 | 63 | 30 | |||

| US, Tampa, Florida, 2005-2006 (100) |

GST-L1 fusion protein-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population- based skin cancer screening |

F/M | 54(18-89) | 311/100 | 25.4/18 | 19.6/4 | 35.1/14.0 | |

| US, Iowa 2000- 2004 (92) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, head and neck cancer study |

F+M | 59.5 (n/s) | 326 | 22.4 | 14.4 | ||

| US, Iowa, 1997- 2000 (103) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Pregnant women at routine |

F | 29 (18-44) | 333 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 0 | 0 |

| obstetric exams Newborn babies |

F+M | 42 hours | 333 | 14.7 | 13.5 | ||||

| US, Boston, MA 1999-2003 (91,97) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Population- based controls, head and neck cancer |

F+M | 61 (25-89) | 550 | 10.7 | |||

| F+M | 61 (25-89) | 548 | 7.8 | 13.9 | 5.7 | ||||

| 25-60 | 245 | 7.8 | 14.3 | 7.3 | |||||

| 61-89 | 303 | 7.9 | 13.5 | 4.3 | |||||

| US, Bethesda, MD 1996-1997 (80) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Blood donors | F | 34.4 (17-78) | 138 | 12.0 | |||

| M | 40.1 (17-72) | 140 | 3.0 | ||||||

| F/M | 17-19 | n/s | 0/0.0 | ||||||

| 20-24 | n/s | 12/0.0 | |||||||

| 25-29 | n/s | 11/5.5 | |||||||

| 30-34 | n/s | 10/3.0 | |||||||

| 35-78 | n/s | 18/2.0 | |||||||

| US, College Park, MD 1992-1993 (84) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

College women seeking routine gynecologic care |

F | 22 (18-40) | 376 | 23.9 | |||

| 18-24 | 60 | 20.3 | |||||||

| 25-30 | 184 | 37.3 | |||||||

| 31-40 | 132 | 37.5 | |||||||

| US, Washington County, Maryland 1974-1975 (108) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 18-74 | 83 | 12 | 25.3 | ||

| US, New Jersey 1992-1994 (87) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

College students |

F | 20 ± 3 | 575 | 14.1 | |||

| ≤20 | 461 | 11.9 | |||||||

| 21-23 | 69 | 17.4 | |||||||

| ≥24 | 45 | 31.1 | |||||||

| US, New Jersey, 1992-1994 (101) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

College students |

F | 20 +/− 3 | 508 | 15 | 13 | ||

| US, New York City, NY 1992-1994 (90) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 31.9 ± 9.9 | 351 | 37.6 | 37.3 | ||

| US, New York State and Illinois 1985- 1987 (106) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, vulvar cancer study |

F | 20-79 | 121 | 11.9 | |||

| US, Portland, Oregon, 1989-1990 (83) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | <20 | 24 | 12.5 | |||

| 20-29 | 346 | 20.5 | |||||||

| 30-39 | 199 | 16.6 | |||||||

| ≥40 | 161 | 14.9 | |||||||

| US, Washington 1990-1995 (11) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

College women | F | 18-20 | 316 | 8.9 | |||

| US, Washington 1990-1995 (82) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

College women visiting student health clinic |

F | 18-20 | 251 | 10.4 | |||

| US, Washington 1993-1996 (86) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls, prostate cancer study |

M | 40-64 | 570 | 8.8 | 2.5 | ||

| US, NHANES 1991-1994 (85,89,93) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey |

F/M | 12-59 | 4108/3110 | 17.9/7.9 | |||

| 12-19 | 867/746 | 6.8/3.5 | |||||||

| 20-29 | 974/755 | 24.7/4.4% | |||||||

| 30-39 | 1020/ 692 |

17.8/11.5 % | |||||||

| 40-49 | 719/559 | 23.9/9.8% | |||||||

| 50-59 | 528/358 | 11/10.2 | |||||||

| F/M | 6-59 | 4513/ 3589 |

5.7/3.6 | ||||||

| 6-11 | 569/623 | 0.7/0.8 | |||||||

| 12-19 | 827/702 | 4.7/2.0 | |||||||

| 20-29 | 931/740 | 6.1/3.3 | |||||||

| 30-39 | 989/665 | 8.3/4.2 | |||||||

| 40-49 | 708/537 | 6.1/5.7 | |||||||

| 50-59 | 489/322 | 5.1/3.9 | |||||||

| F+M | 6-11 | 1316 | 2.4 | ||||||

| 6-7 | 429 | 0.4 | |||||||

| 8-11 | 887 | 3.3 | |||||||

| F/M | 6-11 | 633/683 | 1.2/3.5 | ||||||

| US, 5 cities 1982- 1984 (88) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 20-74 | 486 | 17.7 | 22.8 | ||

| US, 10 cities 1993- 2001 (94) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based controls, prostate cancer study |

M | 65 (60-68) | 1283 | 21.2 | 18.1 | ||

| US, NHANES 2003-2004 (97) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey |

F/M | 14-59 | 2175/ 2128 |

15.6/5.1 | 6.5/1.5 | 17/6.3 | 7.1/2.0 |

| 14-19 | 734/790 | 4/0.2 | 0.9/0.0 | 5.3/0.6 | 1.9/0.1 | ||||

| 20-24 | 228/196 | 13.3/0.3 | 3.8/0.0 | 10.9/3.1 | 4.2/0.8 | ||||

| 25-29 | 191/188 | 16/3.8 | 5/0.3 | 21.9/3.5 | 5.3/2.1 | ||||

| 30-39 | 386/338 | 21.9/6.9 | 9.3/2.5 | 21.4/8.4 | 9.3/3.5 | ||||

| 40-49 | 357/346 | 18.2/7.4 | 9.9/1.5 | 20.6/9.2 | 11.0/1.6 | ||||

| 50-59 | 279/270 | 13.9/7.0 | 4.6/2.6 | 16.1/7.3 | 5.4/2.8 | ||||

| US, 221 sites in Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial, 1993-2003 (96) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Prostate-cancer negative men |

M | >55 | 616 | 18.2 | 5.2 | ||

| US, 21 sites, 2006 (102) |

Epitope- inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from vaccine trials |

F+M | 12.5 (10-17) | 1058 | .3 | 0 | 1.1 | |

| UA, HPFS, 1993- 1995 (104) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Health Professional Follow-up Study |

M | 65.8 | 691 | 8.8 | 5.8 | ||

| US, 15 counties 1986-1989 (105) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based controls, prostate cancer study |

M | 40-79 | 295 | 5.1 | |||

| Multi-country (US, Puerto Rico, and Canada) 1998-2007 (41) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 21 (16-26) | 5485 | 10.0 | 3.1 | 7.3 | 1.5 |

|

| |||||||||

|

Central and South America |

|||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Argentina, Concordia 1997- 2000 (16) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Population- based sample |

F | 44 (≥15) | 902 | 15.7 | 7.9 | ||

| 15-24 | 148 | 13.5 | 6.8 | ||||||

| 25-34 | 197 | 17.8 | 6.6 | ||||||

| 35-44 | 200 | 19.0 | 10.5 | ||||||

| 45-54 | 192 | 16.7 | 8.8 | ||||||

| >55 | 165 | 10.3 | 6.1 | ||||||

| Brazil, São Paulo 1990-1991 (109) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 25-79 | 217 | 24.4 | |||

| 26-43 | 54 | 35.2 | |||||||

| 44-50 | 49 | 26.5 | |||||||

| 51-60 | 53 | 22.6 | |||||||

| 61-78 | 61 | 14.8 | |||||||

| Brazil, Porto Alegre 1994 (110) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Outpatient clinic patients no history of cervical cancer |

F | 15-70 | 974 | 38.7 | |||

| F | 15-24 | 113 | 30.1 | ||||||

| F | 25-34 | 232 | 38.8 | ||||||

| F | 35-49 | 454 | 42.4 | ||||||

| F | 50-70 | 175 | 35.4 | ||||||

| Brazil, São Paulo 2000 (111) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Healthy women with low risk for STIs attending gynecology |

F | 15-25 | 541 | 21.3 | 13.1 | ||

| Columbia, Bogota (2002) (112) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

clinic, baseline for vaccine trial Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 48.9 (25-68) | 147 | 17.7 | 20.4 | ||

| Columbia, Bogota (2005) (114) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 18-55 | 165 | 1.8 | |||

| Colombia, Bogota 2005-2006 (115) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Urban women attending gynecology clinic with normal |

F | 33.5 (15-68) | 104 | 43.3 | |||

| Colombia, Girardot 2006-2007 (113) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

cytology Women attending gynecology clinic <3% abnormal cytology |

F | 41.6 (14-80) | 927 | 43.0 | |||

| 14-24 | 130 | 43.1 | |||||||

| 25-34 | 173 | 45.1 | |||||||

| 35-44 | 257 | 40.1 | |||||||

| 45-80 | 392 | 43.9 | |||||||

| Costa Rica, Guancaste, 1993- 1994 (116,117) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Population- based seroprevalence study |

F | 38 (18-97) | 9949 | 15.4 | |||

| F | <25 | 15.7 | |||||||

| 25-29 | 14.2 | ||||||||

| 30-44 | 18.4 | ||||||||

| 45-64 | 15.0 | ||||||||

| 65+ | 13.7 | ||||||||

| F | 38 (18-97) | 9928 | 15.5 | ||||||

| <25 | 12.7 | ||||||||

| 25-29 | 13.7 | ||||||||

| 30-44 | 18.1 | ||||||||

| 45-64 | 16.7 | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Multi-Regional | 65+ | 15.0 | |||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Colombia and Spain 1985-1988 (118) |

Direct binding L1/L2 VLP- based ELISA |

Hospital/clinic based controls, cervical cancer study |

F | 45.6 (n/s) | 162 | 11.73 | |||

| International (Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru) 2000-2007 (41) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 21 (16-26) | 5749 | 14.0 | 4.2 | 10.2 | 3.3 |

| International, 14 countries 2004- 2005 (119) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 20 (15-25) | 18644 | 16.8 | 11.6 | ||

| International, 47 sites across North America, Central and South America, Europe, Asia, 2003- 2004 (120) |

Epitope inhibition L1 VLP-based immunoassay using Luminex |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F+M | 12.0 (n/s) | 1740 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.9 | |

| International, 6 countries, 2004- 2005 (121) |

Direct binding L1 VLP-based ELISA |

Baseline info from HPV vaccine trials |

F | 12.1 +/− 1.4 | 1341 | 9.4 | |||

Note: If date of sample collection was not specified, study publication date was used in parentheses. If seroprevalence value is between two columns, indicates HPV 16 or 18 OR HPV 6 or 11.

n/s: not specified, F: female, M: male, F+M: females and males combined, F/M: female data/male data

ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay, VLP: Virus-like Particle, SD: Standard Deviation, NHANES: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Table 2. HPV 16 and 18 HPV DNA and seroprevalence data, stratified by continent, country and study year.

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study location, dates, reference |

DNA method* | Mean or median age, age range |

Sample size |

HPV 16 Prevalence (%) |

HPV 18 Prevalence (%) |

HPV 16 Data (%) | HPV 18 Data (%) | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| DNA | Ab | DNA | Ab | DNA+ /Ab+ |

DNA+ /Ab− |

DNA− /Ab+ |

DNA− /Ab- |

DNA+ /Ab+ |

DNA+ /Ab− |

DNA− /Ab+ |

DNA− /Ab− |

||||

| Nigeria, Ibadan 1997-2000(16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 922 | 3.3 | 27.0 | 2.0 | 24.8 | 1 | 2.3 | 26.1 | 70.6 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 24.3 | 73.8 |

| South Africa, near Cape Town (2008) (19) |

Reverse line blot assay |

44 (18-59) | 1002 | 3.3 | 44.1 | ||||||||||

| Asia-Pacific (8 countries) 2000-2007 (41) |

Type-specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 6, 11) |

21 (16-26) | 806 | 4.6 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 1.6 | ||||||||

| China, Gansu 2007-2008 (34) |

Type specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51,52, 56, 59, 68, 6, 11, 42, 43, 44, 53, 66, CP8304) |

38.9 (n/s) | 50 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 88.0 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 98.0 |

| Japan, n/s 2006 (37) |

SPF10-LiPA and type-specific PCR for HPV 16 and 18 |

23 (20-25) | 1040 | 6.5 | 17.3 | 4.0 | 15.8 | ||||||||

| Mongolia, Ulaanbaatar 2005 (29) |

Consensus PCR (GP5+/6+) |

n/s (15-59) | 969 | 6.1 | 23.0 | 2.5 | 19.6 | 2.1 | 4.0 | 20.9 | 73.0 | 0.4 | 2.1 | 19.2 | 78.3 |

| South Korea, Busan 1997-2000 (16,26) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (20-74) | 860 | 1.3 | 5.9 | 0.4 | 9.0 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 5.5 | 93.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 9 | 90.7 |

| South Korea, Busan 2002 (28) |

Consensus PCR (SPF10) |

n/s (15-29) | 648 | 1.2 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 5.9 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 96.5 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 4.0 | 94.9 |

| Thailand, Lampang 1997- 2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 1018 | 1.2 | 15.1 | 0.6 | 12.2 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 14.3 | 84.5 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 12.1 | 87.3 |

| Thailand, Songkla 1997-2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 704 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.6 | 97.0 | 0 | 0.6 | 2.7 | 96.7 |

| Vietnam, Hanoi 1997-2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 957 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.5 | 99.4 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 99.7 |

| Vietnam, Ho Chi Minh City 1997- 2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 803 | 2.9 | 20.9 | 0.9 | 11.6 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 20 | 77.1 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 11.5 | 87.7 |

| Europe, multi- country, (16 countries) 2000- 2007 (41) |

Type-specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 6, 11) |

19.7 (16-24) | 9131 | 9.5 | 10.2 | 4.4 | 3.7 | ||||||||

| Czech Republic, N/S (1999)(73) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

32.4 (20-77) | 165 | 10.3 | 14.6 | 1.2 | 14.6 | ||||||||

| Finland, Turku 1998-2001(51) |

Consensus PCR (GP5+/6+) |

25.5 (18-38) | 286 | 9.3 | 34.9 | 1.9 | 21.5 | 5.0 | 4.3 | 28.6 | 62.1 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 19.6 | 78.6 |

| Norway, Oslo 1991- 1992 (57) |

Consensus PCR (general nested primer pairs; self-designed) |

32.8 (20-44) | 234 | 7.7 | 16.7 | 1.4 | 6.3 | 14.9 | 77.5 | ||||||

| Norway, Oslo, Trondheim, Levanger 1998- 2000 (58) |

Type-specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 6, 11) |

21.2 (16-24) | 896 | 16.3 | 16.2 | 7.3 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 8.5 | 75.1 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 3.7 | 89.1 |

| Spain, Barcelona 1997-2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 908 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 98.6 | 0 | 0 | 3.1 | 96.9 |

| Sweden, Karlstad 1989-1990 (61) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

16.1 (15-17) | 98 | 2.4 | 3.1 | ||||||||||

| Sweden, Vasterbotten 1987- 1993 (62) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11, GP5+/6+) |

40 (29-61) | 142 | 1.0 | 16.0 | 0.0 | 15.0 | ||||||||

| North America, 2 countries 1998- 2007 (41) |

Type-specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 6, 11) |

20 (16-25) | 2907 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 2.3 | 3.1 | ||||||||

| US, New Jersey 1992-1994 (87) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

20 (17-23) | 415 | 4.0 | 13.7 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 11.5 | 84.5 | ||||||

| US, College Park, MD 1992-1993 (84) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

22 (18-40) | 376 | 7.4 | 23.9 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 20.5 | 72.1 | ||||||

| US, Washington State 1990-1995 (11) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

19 (18-20) | 293 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 6.1 | 87.4 | ||||||

| US, New Jersey 1992-1994 (101) |

Southern blot hybridization and Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

20 (17-23) | 508 | 5 | 15 | 2 | 13 | ||||||||

| US, Iowa 1997- 2000 (103) |

Consensus PCR (MYO9/11) |

29 (18-44) | 333 | 6.6 | 14.1 | 2.4 | 13.8 | ||||||||

| Argentina, Concordia 1997- 2000 (16) |

Reverse-line blot analysis of GP5+/6+ PCR |

44 (15->55) | 902 | 4.1 | 15.7 | 1.9 | 7.9 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 13.6 | 82.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 7.2 | 90.9 |

| Brazil, São Paulo 1990-1991 (109) |

Combination of general and type specific primers, PCR |

n/s (26-78) | 192 | 5.2 | 24.4 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 20.8 | 74.0 | ||||||

| Costa Rica, Guancaste 1993- 1994 (116) |

Consensus PCR (MY09/11) |

38 (18-97) | 9112 | 3.5 | 15.4 | 1.3 | 15.5 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 14.6 | 81.8 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 15.8 | 82.9 |

| Colombia and Spain 1985-1988 (118) |

Consensus PCR (MY74/75) |

45.6 (n/s) | 134 | 1.5 | 11.7 | ||||||||||

| International, 6 countries 2000- 2007 (41) |

Type-specific PCR (HPV 16, 18, 6, 11) |

20.5 (16-24) | 5623 | 8.2 | 14.0 | 3.0 | 4.2 | ||||||||

| International, 14 countries 2004- 2005 (119) |

SPF10-LiPA and type-specific PCR (HPV 16 and 18) |

20 (15-25) | 18433 | 5.4 | 16.8 | 2.3 | 11.6 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 13.9 | 80.7 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 10.6 | 87.1 |

All studies with HPV DNA and serology data had only female participants. For additional study data, including serology assay and serology sample size, please see table 1

Abbreviations: n/s: not specified, Ab-Antibody, DNA+/Ab+: DNA positive and Antibody positive, DNA+/Ab−: DNA positive and Antibody negative, DNA−/Ab+: DNA negative and Antibody positive, DNA−/Ab+: DNA negative and Antibody negative, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, GP: General Primer, SPF: short primer fragment, LiPA: line probe assay

Results

Serology results

Of over 2,000 identified abstracts, 117 studies were included in this review (Table 1). Most study populations were from Europe (35%), followed by North America (27%), Asia and Australia (19%), Central and South America (8%), and Africa (6%). Study participants’ ages ranged from a few hours to over 90 years. Serological antibodies were typically detected with ELISA (78%), while Competitive Luminex Assay (12%), GST Capture Assay (9%), and GFP pseudovirus neutralization assay (2%) were used less frequently.

Age-specific HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalence

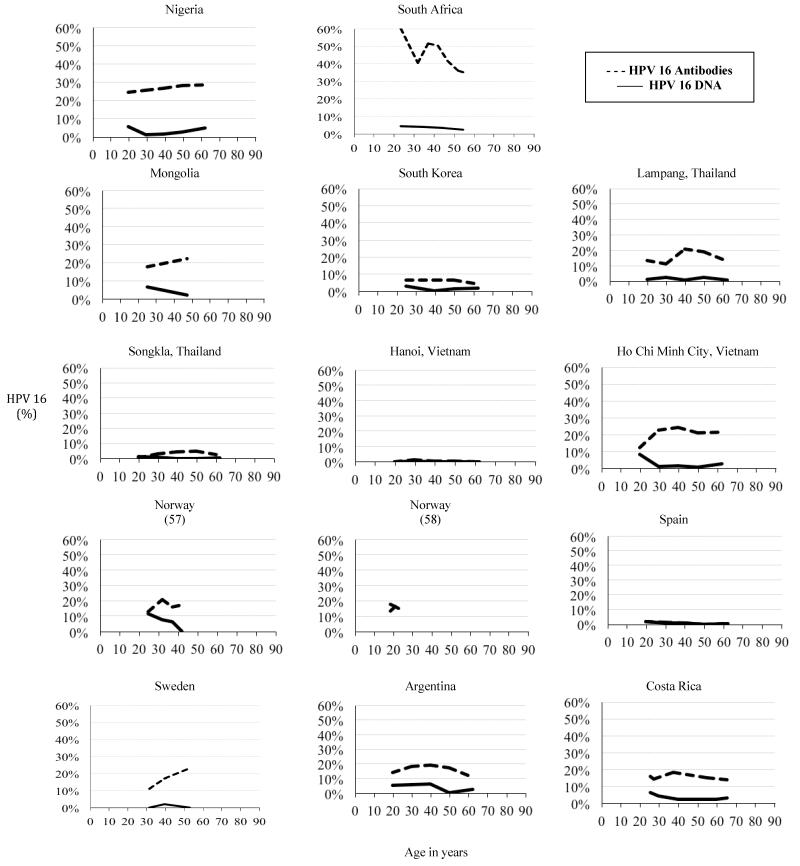

Among studies restricted to women, HPV 16 antibody prevalence tended to be higher in Africa, Central and South America, and North America, as compared with Asia, Australia, and Europe (Figure 1). HPV 16 seroprevalence generally peaked in women aged 25-40 years and decreased or plateaued in older ages. Although HPV 16 seroprevalence generally followed this pattern across the majority of studies, there were several exceptions including Mongolia, Nigeria, and Sweden in which HPV seroprevalence appeared to continue to increase in later ages. HPV 18 prevalence tended to be lower than HPV 16, and peaked slightly later in age.

Figure 1.

Age-specific prevalence of HPV 16 DNA and antibodies against HPV 16 for studies with age-trend data, stratified by study area (16,19,29,57,58,62,116). All studies with age-trend data had only female participants.

Africa

HPV seroprevalence data were available from Mali (15), Nigeria (16), South Africa (17-21), and Tunisia (22,23); age-trend data are shown in supplementary Figure 1A-B (online). HPV 16 seroprevalence was lowest in South African children at 2.9%, (age range 8-12 years) (18), and highest in clinic-based control women from Cape Town, South Africa at 60% (18-30 years) (19). Most African studies had a limited age range, making age trends difficult to identify. Only one study from South Africa presented age-trend data from childhood to adulthood, showing gradual increases in HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences from age 8 to 83 years in a combined gender population (18). Other studies however, showed either a decline during childhood or variable seroprevalence values across age (17), and conflicting trends continued in HPV 16 data from older African participants as well. HPV 18 seroprevalence ranged from 3.3% in female children aged 2 to 12 years in South Africa (18) to 27% in women aged 25-35 years in Nigeria (16), and age-trend data were again conflicting and sparse with seroprevalence values similar to HPV 16 levels. Overall, the approximate average of HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences in Africa were around 30% across all ages.

Asia and Australia

Asia and Australia seroprevalence data were generally from East Asia (16, 24-37), with one Central Asian study (38), two Australian studies (39,40) and one multi-country study (41) (Supplementary Figure 1C-D). HPV 16 seroprevalence in women increased from negligible in childhood, to a peak around 25% in women aged approximately 40 years, and generally decreased among older women. The approximate average HPV 16 seroprevalence was about 15% across all ages. HPV 18 had a similar age trend, though with a relatively lower seroprevalence. Women from Gansu, China (34) (mean age 39 years) had the lowest seroprevalence at 0% for HPV 16 or 18, while Mongolian women (29) (35-39 age group) had the highest seroprevalence for HPV 16 or 18 at 34%. HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences were generally lower in male populations than among female populations of corresponding age.

Europe

Data from Western Europe were available from Austria (42-45), Finland (46-51), Germany (52-54), Italy (40,55), The Netherlands (10,40,56), Norway (57,58), Spain (16,59), Sweden (60-69) and the United Kingdom (70,71). The only studies from Eastern Europe were from the Czech Republic (72-74). Some studies combined multiple European countries (41,75-77) (Supplementary Figure 1E-F).

Girls less than 15 years old typically had HPV 16 seroprevalences less than 5%. HPV 16 seroprevalence generally increased from childhood to a peak in the 25-50 year-old age group, being as high as 34.9% in a group of pregnant Finnish women (mean age 26 years) (51). The lowest HPV 16 seroprevalence in adults (women 20-35 years of age) was 1.2% in Spain (16). HPV 16 seroprevalence was typically around 10-25% in women in their forties and fifties, but age trend data were scarce. In women older than 50 years old, HPV 16 seroprevalence ranged from 0.4-35% (16,54,72) but was generally lower than at earlier ages.

As with other geographic regions, HPV 18 seroprevalence in European women was generally lower than HPV 16 seroprevalence with an approximate average around 5-8% across all ages. HPV 18 seroprevalence was also characterized by an increase from childhood to 25-40 years, after which the age-trend shown by different studies varied. Studies with combined genders had similar findings to women alone, though with overall lower HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalence. Male adult populations had the lowest HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences in Europe.

North America

Except for two studies from Canada (78,79), two from Jamaica (80,81), and one combined Canadian-U.S.-Mexico study (41), most North American seroprevalence data came from the United States (11,82-108) (Supplementary Figure 1G-H). Children younger than 15 years old had HPV 16 seroprevalences below 3% in every study except one: this study reported on newborn infants and their mothers and both groups showed equivalent seroprevalences of 14.7% in both genders (103). HPV 16 seroprevalence generally increased to 10-20% among young girls in their teens and early twenties, although was as low as 0% in blood donors (17-20 years) in Maryland (80). Seroprevalence generally increased to peak in women 30-40 years old, as high as 41% in Jamaica (80). HPV 16 seroprevalence then generally decreased to 10-20% in women 40 years and older. Four studies had age-trend U.S. national HPV 16 seroprevalence data (85,89,93,97). Data from 1991-1994 had the highest seroprevalence at 24.7% in 20-29 year-olds, with a decrease among women in their thirties and a secondary peak among those in their forties (85). Data from 2003-2004 were similar. The approximate average HPV 16 seroprevalence was around 20% across all ages.

HPV 18 seroprevalence in North America appeared to be lower than that of HPV 16. HPV 18 seroprevalence in females generally remained between 5-20%, except for one study from New York having a seroprevalence of 37% (mean age 32 years) (90). Only one U.S. study presented age-trend HPV 18 data for female-only populations, which peaked in 40-49 year-olds and then decreased (97). All North American studies with combined gender seroprevalence data showed lower seroprevalence than studies with female-only populations. HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences in North American male-only populations were also typically lower than in similarly aged female populations

Central and South America

Central and South American seroprevalence data were available for women from Argentina (16), Brazil (109-111), Colombia (111-115), and Costa Rica (116,117) (Supplementary Figure 1I-J). No data on HPV seroprevalence in children and adolescents under age 15 were available (16). HPV 16 seroprevalence varied greatly between different populations but were generally higher than in other world regions with an approximate average around 25% across all ages. Age trends seemed remarkably flat across age groups; in one Colombian study, HPV 16 seroprevalence was over 40% regardless of age (113). However, in general HPV 16 seroprevalence levels did increase slightly from age 18 years to age 30-40 years with several studies showing decreases in later years (16,110).

Very little data were available on HPV 18 seroprevalence in Central and South America; only two studies had age-trend data, from Costa Rica (116) and Argentina (16). Both studies showed a seroprevalence peak in women aged 30-44 years, followed by a slight decrease with increasing age. Generally, HPV 18 seroprevalence in Central and South America was less than 20%. No studies were found with eligible data on HPV serum antibody prevalence in men.

Multi-regional

Five studies combined serology data from multiple regions (41, 118-121), all of which presented baseline data from control and experimental groups participating in HPV vaccine or cervical cancer trials (average age 22 years). These women had HPV 16 seroprevalences ranging from 9% to 17% (41,118,119,121) and HPV 18 seroprevalence values ranging from 4 to11.6% (41,119). One study only presented data for HPV 16 and 18 combined, and had a low prevalence of 1.0% (120).

HPV 6 and 11 seroprevalence

Fewer studies had HPV 6 and 11 seroprevalence data compared to those with HPV 16 and 18, with only one study from Africa (21), four from Asia/Australia (25,36,39,40), fourteen from Europe (40,42,44,46,47,48,49,51,52,58,60,63,69,71), eight from North America (82,91,95,97,100,102,103,108), and one international study (41) publishing HPV 6 or 11 data.. Globally, HPV 6 seroprevalence values were similar or higher than those of HPV 16 and higher than those of HPV 18 in the same population. The highest published HPV 6 seroprevalence was among 18-38 year old women from Finland (51) at 53%. HPV 11 had the lowest seroprevalence values of all HPV types included in this review. The highest HPV 11 seroprevalence was 35% among women aged 18-89 in Florida (102), although all other HPV 11 prevalences among women ranged from 0 to 22% worldwide. Female seroprevalences for both HPV 6 and 11 were higher than those for males and both peaked at a similar age to HPV 18, later than HPV 16.

HPV DNA and Serology Prevalence

Twenty-three studies with both DNA and serology data from the same population were identified (Table 2), all of which had only female data. Many included multiple geographical regions (11,16,19,26,28,29,34,37,41,51,57,58,61,62,73,84,88,101,103,109,116,118,119), and most populations were from Asia and Australia (31%), Europe (23%), North America (17%) or Central and South America (14%). Two studies (6%) were from Africa.. The mean age of study participants ranged from 16 to 46 years. HPV infection was ascertained by PCR techniques in all studies with both DNA and serological outcomes. Serum antibodies were detected by L1 or L1/L2 VLP direct ELISA in most studies (80%), while others used the competitive Luminex Assay (12%), GST Capture Assay (4%), or GFP pseudovirus-based neutralization assay (4%).

For HPV 16 and 18, age-stratified DNA prevalence peaked around 20-30 years and generally declined with age, while the corresponding seroprevalence peaks were consistently later at 35-55 years of age (Figure 1). Some studies in Africa and Central and South America showed an increase in HPV 16 and 18 DNA prevalence after women reached age 50 (16,118), consistent with the ‘U-shaped DNA prevalence curve’ (14). Seroprevalence of HPV 16 and 18 was consistently higher than DNA prevalence. In studies with data for multiple age groups within the same population, higher DNA prevalence rates in younger age groups did not always correlate with higher seroprevalence rates in older age groups.

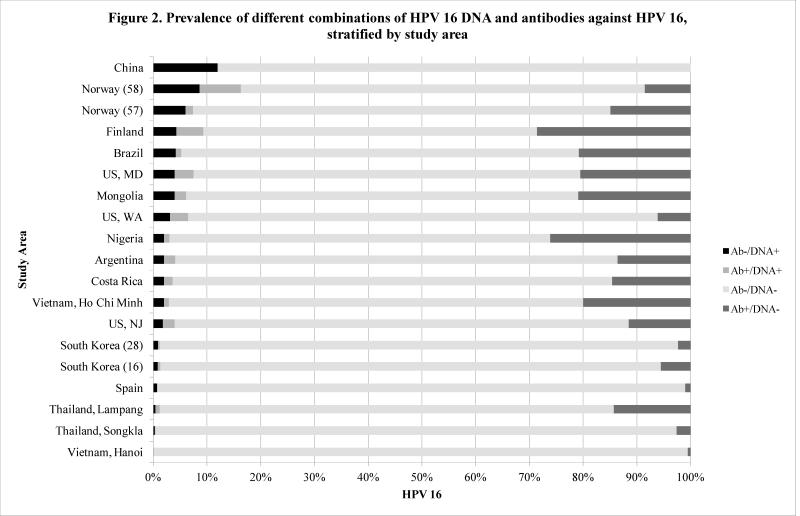

DNA and serology prevalence data for HPV 16 in which each woman’s DNA and serology status were identified were available from nineteen study sites, and such data for HPV 18 were available from nine study sites. Women in these studies were classified into four categories: antibody positive/DNA positive, antibody positive/DNA negative, antibody negative/DNA positive, and antibody negative/DNA negative, as shown in Figure 2. Women were most often antibody negative/DNA negative, with proportions ranging from 62.1% of the study population in Finland (51) to 99.4% in Hanoi, Vietnam (16).. The antibody positive/DNA negative group had proportions ranging from 0% in China (34) to 28.6% in Finland (51), indicating previous HPV exposure without current infection. For HPV 16, the antibody positive/DNA positive category was the smallest, with its proportion of the total population ranging from 0% in Spain (16) to 7.7% in Norway (58). The percentage of women dually serology/DNA positive was equal or less than 1% in more than half the studies. Only slightly larger was the antibody negative/DNA positive group, with proportions ranging from 0% in Hanoi, Vietnam (16) to 12% in China (34).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of different combinations of HPV 16 DNA and antibodies against HPV 16, stratified by study area. All studies with DNA and antibody data had only female participants.

Less than 20% of HPV 16 antibody positive women were also HPV 16 DNA positive in seventeen out of nineteen studies. In all but two studies with HPV 18 data, less than 10% of antibody positive women were also DNA positive, and the highest percentage of women dually positive for HPV 18 antibodies and DNA was again found in Norway (58) at 2.7%. HPV 16 showed higher percentages of dual positivity than HPV 18 in all studies with data for both types. This finding coincides with a recent IARC review that showed a much higher likelihood of DNA and antibody dual positivity for HPV 16 (>30%) than for HPV 18 (0-30%) in seven out of eight sites (16).

Discussion

This review of more than 138,000 study participants worldwide found that HPV seroprevalence was variable and depended on many factors, including geographic location, gender, and age. These differences across studies are consistent with broad ranges of HPV 16 and 18 sero- and DNA prevalence previously observed (28,85,87,116). Both HPV 16 and 18 seroprevalences were generally higher in Africa, Central and South America, and North America, and lower in Europe, Asia, and Australia. In studies with age-matched participants of both genders, women consistently had similar or higher HPV serology for all serotypes, suggesting that women have a higher risk of acquiring HPV or seroconverting than men. Furthermore, age was strongly associated with both HPV sero- and DNA prevalence. HPV 16 seroprevalence generally peaked in women aged 25-40 years, and at slightly later ages for HPV 18. HPV 16 and 18 DNA prevalence peaked in women aged 15-30 years and either declined or peaked a second time after age 50, depending on the geographic region (14,16). Thus, female cohorts aged 15-40 could be simultaneously experiencing an increase of HPV seroprevalence and a decrease of HPV DNA infection – a phenomenon explainable if persistent infection is sometimes necessary to cause detectable antibody responses (16,116), or if a delay exists between initial exposure and seroconversion (122). The decline in HPV seroprevalence observed in many older populations could represent loss of antibodies over time as HPV exposure becomes less frequent or ceases (116), or could reveal a cohort effect for this age group. Our review generally showed that HPV 16 seroprevalence was higher than HPV 18 seroprevalence, in agreement with previous HPV DNA studies (26,123,124) but in contrast to the 2010 four-continent IARC pooled analysis that found higher seroprevalence of HPV 18 than HPV 16 (16).

The relationship between HPV sero- and DNA prevalence rates is also interesting. Populations with low HPV seroprevalence also generally had low DNA prevalence, an expected finding as fewer infections in a population would result in lower population antibody positivity. Populations with high HPV seroprevalence did not necessarily have high HPV DNA prevalence, which likely reflects the fact that HPV antibodies are a marker of past, not necessarily current infection in most seropositive women. In populations with age-trend data, higher DNA prevalence in younger age groups did not necessarily correlate with higher seroprevalence in older age groups (Figure 1). If seroprevalence is a reliable measure of cumulative exposure, a population with high DNA infection rates among young women should also have high seroprevalence rates among older women. This apparent incongruity could be due to cohort effects in which the older women in these studies did not have high DNA prevalence rates when younger. These data could also suggest that seroconversion does not necessarily follow HPV infection, or that serologic positivity can be lost over time. Data from Costa Rica support this hypothesis, showing that serologic status results from both seroconversion and clearance, with only 55% of 1,216 HPV 16 seropositive women remaining positive after 5-7 years (125). Another possibility is that highly sensitive DNA detection methods, such as PCR, may overestimate prevalent HPV infection by detecting deposition of viral DNA in the genital tract that would be cleared before infection of epithelial cells is established (126). Thus, women in whom HPV DNA is detected at several visits may be significantly more likely to seroconvert than are women with only one HPV DNA-positive visit (122).

Global data for populations with both HPV 16 and 18 sero- and DNA prevalence information for each participant showed the vast majority of subjects were doubly antibody and DNA negative (82.9 ± 4.9% for HPV 16) and thus would receive optimal benefits from HPV vaccination. Another 12.2 ± 4% of subjects were antibody positive but DNA negative, and there is some evidence based on relatively small sample size studies that vaccination may still have benefits for women who are antibody-positive but DNA-negative for a specific HPV vaccine type (123,124). It has been shown that prophylactic HPV vaccines do not increase the clearance of pre-existing HPV infection among women who are DNA-positive at the time of vaccination (6,121), but only a small percentage of women in these studies fell into either the antibody negative/DNA positive or antibody positive/DNA positive categories.

This review has several strengths; to our knowledge, it is the first to examine combined HPV sero- and DNA prevalence. Our strict inclusion and exclusion criteria enable comparison across populations and geographic areas. Many studies were included, ranging from local populations to large national surveys. A potential limitation was the inclusion of only HPV types for which vaccines are currently available, because other carcinogenic HPV types cause an estimated 20-30% of invasive cervical cancers (3,127). We also excluded high-risk populations because our goal was to investigate HPV seropositivity and associated DNA positivity among relatively low risk women. However, both antibody and DNA positivity may have been lower in this population due to possibly higher false positivity (e.g. lower specificity) of both assays than among higher-risk populations with higher HPV DNA viral titers and/or clinically apparent disease. Several studies have identified a higher risk of cervical cancer among women with higher HPV antibody detection (128,129).

The cut-points for HPV seropositivity in ELISA assays and other types of antibody surveys varied across laboratories, and in some cases may have varied across time. These variations in the chosen cut-offs of HPV seropositivity may have further limited our ability to directly compare seroprevalence data across studies in some cases. In addition, meta-analyses were not conducted to determine factors related to differences in HPV seroprevalence across geographical regions. The cross-sectional analyses presented here also limit our review, as longitudinal analyses would permit more reliable estimates of HPV seroconversion among individuals with type-specific HPV incident infections, as well as persistence of antibody responses over time. Several studies have shown a time delay between confirmed HPV infection and HPV seroconversion (122).

Furthermore, the data points in Supplementary Figure 1 represent average ages; in studies with large age groups, data from narrow and wide age ranges are both represented as a single point, perhaps leading to misinterpretation. However, most age groups spanned only 10-15 years. Finally, most available data were for adult women over 26 years of age, despite HPV prophylactic vaccination programs targeting younger ages. Only thirteen studies had age-trend serology data including children under 15 years old, and no studies had data on both HPV sero- and DNA prevalences for this younger age group.

Summary and Implications

Several important points can be drawn from this global review. Sero- and DNA prevalence of oncogenic HPV types were globally more common in women than men and had distinguishable age trends but varied by geographic region. Using HPV serology data, a measure of cumulative exposure, along with HPV DNA data, a measure of acute infection, can contribute to estimating HPV virus exposure on a population level, which is important for vaccine program implementation. Within the 9-26 year-old age group (for whom the HPV vaccine is approved in the United States), many women worldwide have already been exposed to oncogenic strains of HPV, as indicated by HPV 16 seroprevalences ranging from 0-43%. However, among studies with both HPV 16 DNA and seroprevalence data, 81-87% of women in this age group were dually HPV 16 sero- and DNA-negative and 90-98% were HPV 16 DNA-negative. Girls 9-18 years old had even lower ranges of carcinogenic HPV seroprevalence than women aged 19-26. These previous findings and our data together suggest that the large majority of women in the vaccine target age group likely do not have current or past infection with HPV 16, and may obtain optimal protection through HPV vaccination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, Fogarty International Center, Office of AIDS Research, National Cancer Center, National Eye Institute, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, and NIH Office of Women’s Health and Research through the International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988), the American Relief and Recovery Act, and GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. The authors would also like to thank Jie Ting for her literature search assistance. Everyone with significant contribution to the work has been included here. This research was presented orally at the Eurogin Scientific Congress in Lisbon, Portugal in May 2011.

Abbreviations

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- STD

sexually transmitted disease

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- IgA

immunoglobulin A

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- VLP

virus-like particle

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: JS Smith has received research grants, honoraria, or consultancy fees from GSK or Merck within the last five years. No other authors on this manuscript have any conflicts of interest related to this work. A GlaxoSmithKline representative read the article before submission for publication but had no role in study design, analysis of data, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The first draft of the manuscript was jointly written by J Ji, MJ Lin, and SM Tiggelaar. No honorariums, grants, or other forms of payment were given to anyone to produce the manuscript.

Implications and Contribution

This is the first global review of vaccine-associated human papillomavirus sero- and DNA prevalence, which varied by gender, age, and geographic location. Although limited, data among adolescents eligible for prophylactic vaccination suggest that many remain unexposed to carcinogenic HPV types and would benefit from the HPV vaccine.

References

- 1.Human Papillomaviruses . IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC); Lyon, France: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide cancer burden in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1757–65. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Group TFIS Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061741. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa061741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, et al. High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1459–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S, et al. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:743–53. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.743. DOI: 10.1001/jama.298.7.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillner J. The serological response to papillomaviruses. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:423–30. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0146. DOI: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang Y, Brewer NT, Rinas AC, et al. Evaluating the impact of human papillomavirus vaccines. Vaccine. 2009;27:4355–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.008. DOI: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molano M, Van den Brule A, Plummer M, et al. Determinants of clearance of human papillomavirus infections in Colombian women with normal cytology: a population-based, 5-year follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:486–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg171. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwg171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Gruijl TD, Bontkes HJ, Walboomers JM, et al. Immunoglobulin G responses against human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particles in a prospective nonintervention cohort study of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:630–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.9.630. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/89.9.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carter JJ, Koutsky LA, Wipf GC, et al. The natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 capsid antibodies among a cohort of university women. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:927–36. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.927. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho GY, Studentsov YY, Bierman R, et al. Natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 virus-like particle antibodies in young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:110–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-03-0191. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-03-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koshiol J, Lindsay L, Pimenta JM, et al. Persistent human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:123–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn036. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwn036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JS, Melendy A, Rana RK, et al. Age-specific prevalence of infection with human papillomavirus in females: a global review. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:S5–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.009. S1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bayo S, Bosch FX, de Sanjose S, et al. Risk factors of invasive cervical cancer in Mali. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:202–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.1.202. DOI: 10.1093/ije/31.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccarella S, Franceschi S, Clifford GM, et al. Seroprevalence of antibodies against human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 in four continents: the International Agency for Research on Cancer HPV Prevalence Surveys. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(9):2379–88. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0336. DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marais D, Rose RC, Williamson AL. Age distribution of antibodies to human papillomavirus in children, women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and blood donors from South Africa. J Med Virol. 1997;51:126–31. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199702)51:2<126::aid-jmv7>3.0.co;2-9. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199702)51:2<126::AID-JMV7>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marais D, Rose RC, Lane C, et al. Seroresponses to virus-like particles of human papillomavirus types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 in San people of Southern Africa. J Med Virol. 2000;60:331–6. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(200003)60:3<331::aid-jmv12>3.0.co;2-a. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(200003)60:3<331::AID-JMV12>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marais DJ, Constant D, Allan B, et al. Cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and HPV type 16 antibodies in South African women. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:732–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01322-07. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01322-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marais DJ, Rose RC, Lane C, et al. Seroresponses to human papillomavirus types 16, 18, 31, 33, and 45 virus-like particles in South African women with cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Med Virol. 2000;60:403–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(200004)60:4<403::aid-jmv7>3.0.co;2-6. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(200004)60:4<403::AID-JMV7>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marais DJ, Sampson CC, Urban MI, et al. The seroprevalence of IgG antibodies to human papillomavirus (HPV) types HPV-16, HPV-18, and HPV-11 capsid-antigens in mothers and their children. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1370–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20874. DOI: 10.1002/jmv.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achour M, Kahla S, Zeghal D, et al. Analysis of antibody response to HPV 16 and HPV 18 antigens in Tunisian patients. Viral Immunol. 2009;22:7–16. doi: 10.1089/vim.2008.0009. DOI: 10.1089/vim.2008.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Achour M, Kochbati L, Zeghal D, et al. Serological study in Tunisian cervical cancer patients. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2009;57:415–9. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.05.004. DOI: 10.1016/j.patbio.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wideroff L, Schiffman M, Hubbert N, et al. Serum antibodies to HPV 16 virus-like particles are not associated with penile cancer in Chinese males. Viral Immunol. 1996;9:23–5. doi: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.23. DOI: 10.1089/vim.1996.9.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto K, Yoshikawa H, Taketani Y, et al. Antibodies to human papillomavirus 16, 18, 58, and 6b major capsid proteins among Japanese females. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:369–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin HR, Lee DH, Herrero R, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in women in Busan, South Korea. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:413–21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10825. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.10825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]