Abstract

Maintaining the international normalized ratio (INR) within the therapeutic range in patients on oral anticoagulant treatment is a challenge for the physician. Excessive anticoagulation poses the risk of bleeding in patients. Management strategies vary among clinicians although standard guidelines exist for the same. We conducted an audit in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy in our hospital with excessive anticoagulation. This retrospective study was carried out among patients on oral anticoagulant therapy for various thrombotic conditions with at least a single INR recording of 5 or more. Other than demographic details, the type of oral anticoagulant used, indication, duration of treatment, dosage and concomitant use of interacting drugs or alcohol were also recorded. Detail of the nature and site of bleed and management for the same was also noted. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Fifty episodes with INR ≥ 5 (5.0–10.75) were noted in 44 patients (M:F = 1:1). Their age ranged from 20 to 88 years (mean 50.3 ± 16.4 years). The duration of anticoagulant therapy varied from 3 days to 180 months. Of the 43 episodes in patients who had no bleeding, the anticoagulant was stopped on 32 occasions for variable periods with dose reduction in the rest of the patients. Spontaneous bleeding was seen in seven patients (6 major and 1 minor). Among the seven patients with bleeding, other than stopping he oral anticoagulant drug, other measures taken were vitamin K therapy, fresh frozen plasma or packed red cell transfusion. Overall management strategy of patients with high INR was in compliance with standard recommendations.

Keywords: Bleeding, International normalized ratio (INR), Management, Oral anticoagulant

Introduction

The number of patients on oral anticoagulant treatment has increased manifold over the past few decades. Maintaining the international normalized ratio (INR) within the therapeutic range is a challenge for the physician to achieve maximal therapeutic benefit of oral anticoagulants in patients. Adequate anticoagulation reduces the risk of life threatening thrombosis; however there is an increased risk of bleeding complications due to over anticoagulation that may occur during the course of therapy [1]. The risk of bleeding increases with increasing INR in patients on anticoagulation [2] and most minor and major bleeds occur in patients with INR of more than 5 [3]. Physician response to excessive prolongation of INR ranges from simple withholding of anticoagulants to intravenous vitamin K therapy and/or blood/plasma support depending on the presence of active bleeding [3]. Data on management of high INR values in anticoagulated patients has shown that these patients face a significant risk of major hemorrhage [4].

We present an audit in patients on anticoagulant therapy in our hospital with an INR of five or above.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was carried out in a tertiary care hospital in North India. Case records of patients with at least a single INR recording of 5 or more seen over a period of 2 years were studied. These patients were on oral anticoagulant therapy for various clinical indications. Demographic details on age, sex, rural or urban background and education status were also noted.

Other details noted were the type of oral anticoagulant agent used (nicoumerol or warfarin), indication for anticoagulation, duration of treatment, dosage of anticoagulant, whether same or alternating strengths were used and concomitant use of interacting drugs or alcohol. The nature of bleeding, whether minor or major, spontaneous or traumatic and the site of bleeding was recorded. The bleeding was considered to be major if it required treatment, medical evaluation or at least two units of blood [5]. Also noted were the action taken by the clinician after the high INR recording (lowering of dose or stopping the drug), time after which a repeat INR was checked, the dose on which treatment was re-started and number of INRs in the therapeutic range (of the last four consecutive recordings). Therapeutic intervention for the raised INR (vitamin K injection or blood/FFP (fresh frozen plasma) transfusion), clinical response, pre- and post-transfusion hemoglobin, morbidity and mortality in patients was also recorded. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Demographic Information

There were 50 episodes with INR ≥ 5 noted in 44 patients. There were equal number of males and females in the study (M:F = 1:1). The age of the patients ranged from 20 to 88 years with a mean age of 50.3 ± 16.4 years. Twenty-six (59.1%) patients belonged to the urban background while 18 (40.9%) were from rural areas. Of the 50 episodes of high INR, 26 were noted in inpatients and 24 in outpatients.

Duration of Anticoagulant Therapy

The duration of anticoagulant therapy in patients with INR ≥ 5 ranged from 3 days to 180 months. The details of the duration of therapy are shown in Fig. 1. On 24 occasions (48%) when the INR was ≥ 5, the anticoagulant therapy had been initiated within the last 3 months.

Fig. 1.

Shows the duration of oral anticoagulation therapy among patients studied

INR Range

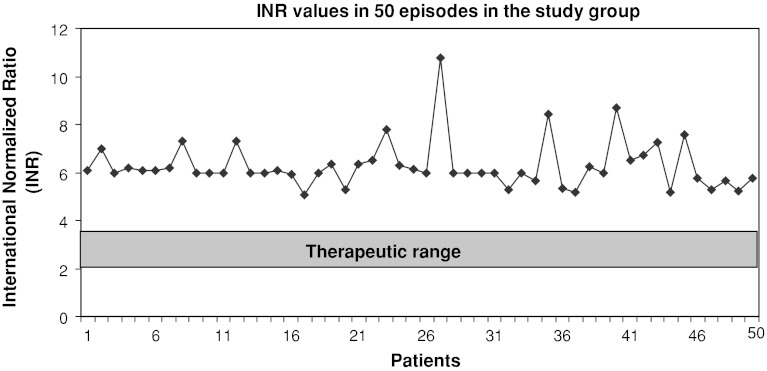

The INR in the patients included in this study ranged from 5.0 to 10.75. Individual INR in these patients is shown in the scatterplot (Fig. 2). For most clinical conditions, an INR range of 2.0–3.0 was considered as therapeutic while for patients with prosthetic valves, a higher INR range of 2.0–3.5 was considered therapeutic. The raised INR was rechecked to confirm the abnormal value only on 4 (8%) occasions.

Fig. 2.

Shows the scatterplot representing individual INRs (≥5) on 50 occasions

Anticoagulant and Strength Used

The anticoagulant drug used in most (98%) of the patients was nicoumerol (acitrom) with only one patient (2%) on warfarin. Same strength of the anticoagulant was prescribed by the clinician in 70% of the patients while 30% of them were on alternating strengths.

Indications for Anticoagulation

The clinical indications for which anticoagulation was started in patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Indications for oral anticoagulant therapy in 44 patients

| Indication for anticoagulation | Number of Patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Prosthetic valve replacement | 12 | 27.3 |

| Chronic rheumatic valvular heart disease | 12a | 27.3 |

| Venous/arterial thromboembolism | 9 | 20.4 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 | 11.4 |

| Embolic/thrombotic stroke | 3 | 6.8 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 4.5 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1 | 2.3 |

aOf these 12 patients, 6 had atrial fibrillation while 6 were in sinus rhythm

Action Taken in Non Bleeding Excessively Anticoagulated Patients

Of the 43 episodes in patients with INR ≥ 5 who had no bleeding, the anticoagulant was stopped on 32 occasions for variable periods. The detail of the duration of anticoagulation stoppage is given in Fig. 3. In one patient, no documentation was available on the action taken. In the remaining 10 occasions, the dose of the anticoagulant drug was reduced.

Fig. 3.

Shows the duration of stoppage of anticoagulation therapy in 40 non bleeding patients who were managed conservatively. In two patients, the anticoagulant therapy was stopped indefinitely while no documentation of the action taken was present in one patient

Bleeding in Excessively Anticoagulated Patients

Of the 50 episodes of INR ≥ 5, seven (14%) were associated with bleeding which was spontaneous in nature. Major bleeds were seen in six patients and minor in one patient. Duration of anticoagulant treatment in four of the seven patients with bleeding was less than 2 months. The detail of the site of bleeding in these patients and the INR at the time of bleeding is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Nature and site of bleeding in seven patients along with INR at the time of bleed

| Nature of bleed | Patient | INR at time of bleed | Site of bleed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major | |||

| Patient 1 | 5.41 | Sub-arachnoid/Extradural | |

| Patient 2 | 5.71 | Gastrointestinal tract | |

| Patient 3 | 6.13 | Gastrointestinal tract | |

| Patient 4 | 5.80 | Gastrointestinal tract | |

| Patient 5 | 6.21 | Pelvic hematoma | |

| Patient 6 | 6.50 | Genito-urinary tract | |

| Minor | |||

| Patient 7 | 5.68 | Oral cavity | |

Treatment in Excessively Anticoagulated Bleeding Patients

Among the seven patients who had bleeding, other than stopping the oral anticoagulant drug, other measures taken were vitamin K therapy, FFP or packed red cell transfusion. Detail of the therapy given in these patients is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Treatment in excessively anticoagulated bleeding patients. Patient 7 had a minor bleed

| Patient | Dose of vitamin K (mg) | FFP (units) | RBC transfusion (units) | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 50 | 4 | 1 | None |

| Patient 2 | No | No | No | None |

| Patient 3 | 20 | 4 | 3 | None |

| Patient 4 | No | 2 | 3 | None |

| Patient 5 | 50 | 5 | No | None |

| Patient 6 | No | No | No | None |

| Patient 7 | No | No | No | None |

Restarting the Anticoagulant

After the high INR reports in 39 patients (32 non bleeders and 7 bleeders) in whom the anticoagulant was stopped, the anticoagulant drug was restarted with the reduced dose on 30 occasions. The same dose was restarted in three occasions. Anticoagulation was stopped indefinitely in two patients because of co-morbid conditions while in two patients anticoagulation was discontinued as they were taken up for elective surgery. One patient was lost to follow up and in one patient, the anticoagulant drug was changed (acitrom to warfarin).

Drug Interactions and Co-Morbid Illness

Two patients were on concomitant antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and clopridogrel) while one patient was on low molecular weight heparin. One patient had cirrhosis of the liver.

Discussion

Our study has shown that majority of the patients who had excessive anticoagulation were managed in line with standard guidelines. The management ranged from withholding the anticoagulant to treatment with vitamin K, FFP and/or blood transfusion.

Standard guidelines exist on managing patients who are excessively anticoagulated [6]. However, adherence to these guidelines is variable [7].

The high INR value was rechecked on only four (8%) occasions in the present study. In a study by Bussey et al. [8], 10–20% of laboratory INRs were erroneous and almost one half of them were higher than 4.5. Laboratory errors need to be considered carefully before taking action on an unusually high INR value. Rechecking abnormally high INRs should be done to avoid inappropriate management decisions in patients with unexpectedly high INRs that do not conform to the clinical presentation.

Simple withholding of anticoagulation and waiting for the INR to fall within the therapeutic range is a commonly employed measure by physicians in excessively anticoagulated patients who have no significant bleeding.

In the present study, on 43 (86%) occasions when the INR was ≥5 in non-bleeding patients, conservative management was done by discontinuing or reducing the dose of the anticoagulant. The anticoagulant was stopped on 32 occasions, dose reduction was done on ten occasions, while there was no documentation available for one patient.

Standard recommendation for managing patients with INR between 5.0 and 9.0 includes omitting or lowering the dose of anticoagulant, monitoring the INR more frequently and resuming therapy at a lower dose when INR is at therapeutic level [4, 6, 9]. In our study, among the 32 patients in whom anticoagulation was discontinued, the therapy was restarted with a reduced dosage in 26 patients.

The conclusion from two large case-series in excessively anticoagulated patients with INR > 6.0 was that conservative treatment of non bleeding patients was safe and more cost effective than administration of vitamin K [4, 10].

Lousberg et al. studied 301 episodes of excessive anticoagulation (INR > 6.0) among 248 patients. Eighty-three percent of the (83%) patients were managed conservatively by temporary discontinuation of warfarin sodium therapy until the INR was in a therapeutic range. Only two episodes (0.8%) of major bleeding were seen in the patients managed conservatively [4].

Glover and Morrill retrospectively reviewed 51 patients with high INRs. Forty-eight (94%) patients included in their study were managed conservatively, and only three (6%) received phytonadione. Conservative management was shown to be safe and cost-effective when the INR was between 6.0 and 10.0 [10].

A retrospective review in 85 patients who were over-anticoagulated with INR of ≥6.0 showed that 20% of the patients who received vitamin K therapy experienced no difference in the clinical outcome compared with those managed conservatively. Conservative management of critically high INR values appeared to be as efficacious as intervention with vitamin K therapy [11].

The risk of bleeding in patients on anticoagulants rises significantly with age and with the achieved intensity of anticoagulation, and is dependent on the type of coumarin derivative that is used [12]. In our study however, the mean age of patient who had bleeding was 41.7 years compared to the overall mean of 50.3 years in all patients with INR ≥ 5. In nearly all (98%) of the episodes of excessive anticoagulation in our study, the patients were on nicoumerol derivatives.

In a study by Hyleck et al., [13] 5 of 114 asymptomatic patients with INR > 6 who were managed with temporary warfarin withdrawal developed major or life threatening bleeding within 2 weeks of their elevated INR value being recorded. None of the 43 patients with high INR in our study who were managed conservatively had bleeding complications.

Two patients in the present study with high INR who were asymptomatic and in whom anticoagulation was stopped were given vitamin K. There was no morbidity in these patients.

Studies have shown that the risk of major hemorrhage in patients with INR > 5.0 increases exponentially [3, 14, 15].

In the present study, six (12%) of the patients developed major bleeding while one (2%) patient had a minor bleed. There was no mortality in the present study.

Murphy et al. audited 131 patients with INR > 8.0. In their study, 12.9% of the patients had bleeding which is comparable to our study [16].

In the study by Hylek et al. in 114 patients with INR of more than 6.0, 8.8% of the patients had significant bleeding similar to our findings. However, two of the patients with major bleed in their study expired [13].

In all six (12%) patients in our study who had major bleeds following excessive anticoagulation, the anticoagulants were withdrawn. Two of the patients were given intravenous vitamin K, FFP and packed red cell transfusion. One patient was given vitamin K and FFP while another patient was transfused FFP and packed red cells. In two of the patients with major bleeds, other than stopping the anticoagulant drug, no other intervention was done. Despite the variable therapeutic modalities followed in patients with major bleed (including simple withholding of the anticoagulant therapy in two patients), no significant morbidity or mortality was seen in any patient.

In our study, the therapeutic intervention in over anticoagulated patients who had bleeding was in compliance with standard guidelines. In patients with significant bleeding due to excessive anticoagulation, the drug should be stopped and vitamin K should be administered along with FFP or packed red cells depending on the degree of bleeding and presence of associated risk factors [6].

In the lone patient with minor oral bleed, the anticoagulant was temporarily discontinued which lead to cessation of bleeding.

Duration of anticoagulant treatment in four of the seven patients with bleeding was less than 2 months. In a study in 65 patients with INR ≥ 6.0 when compared to the control group, high-INR patients were significantly more likely to have been anticoagulated for less than 6 months [11].

Among the seven patients who had bleeding while on anticoagulation, of the last 4 INRs analyzed, three patients had no INR in the therapeutic range, one patient had only one INR in the therapeutic range while another patient had all four INRs in the therapeutic range. No INR monitoring prior to the high INR was done in one patient while documentation of the INR was not available in one patient.

In our study, two patients were on concomitant antiplatelet drugs (aspirin and clopridogrel) while one patient was on low molecular weight heparin. One patient had cirrhosis of the liver. None of these patients had bleeding complications.

In a review of 85 episodes in over-anticoagulated patients with INR of ≥6.0, compared to the control group, high-INR patients were significantly more likely to manifest the presence of alcoholism or liver disease, and to have had the addition of a medication known to interact with warfarin [11].

Our study being a retrospective analysis has some limitations. Since the high INR values were rechecked on only four occasions, laboratory errors rather than actual excessive anticoagulation could have played a role. Also, the role of drug and dietary interactions was difficult to ascertain from the case records.

Conclusions

Majority of the patients who had excessive anticoagulation were managed conservatively by withholding the anticoagulant drug. Patients who had bleeding were given vitamin K, FFP and blood transfusion wherever indicated. Overall management strategy of patients with high INR was in compliance with standard recommendations.

References

- 1.Ansell JE. Oral anticoagulant therapy—50 years later. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:586–596. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410050024005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landefeld CS, Beyth RJ. Anticoagulant related bleeding: clinical epidemiology, prediction, and prevention. Am J Med. 1993;95:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90285-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Wintzent AR, van der Meer FJ, Vandenbroucke JP, Briet E. Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:11–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507063330103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lousberg TR, Witt DM, Beall DG, Carter BL, Malone DC. Evaluation of excessive anticoagulation in a group model health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:528–534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fihn SD, McDonnel M, Martin D, Henikoff J, Vernes D, Kent D, et al. Risk factors for compilations of chronic anticoagulation. A multicenter study. Warfarin optimised outpatient follow-up study group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:511–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists. American college of chest physicians. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, 8th edn. Chest. 2008;133:160S–198S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devine EB, Hopefl AW, Wittkowsky AK. Adhrence to guidelines for the management of excessive warfarin anticoagulation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2009;27:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s11239-008-0232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bussey HI, Chiquette E, Bianco TM, Lowder-Bender K, Kraynak MA, Linn WD, et al. A statistical and clinical evaluation of fingerstick and routine laboratory prothrombin time measurements. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:861–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ansell J, Hirsh J, Dalen J, Bussey H, Anderson D, Poller L, et al. Managing oral anticoagulant therapy. Chest. 2001;119:22S–38S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.22S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glover JJ, Morrill GB. Conservative treatment of overanticoagulated patients. Chest. 1995;108:987–990. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigden ML, Kay C, Le A, Graydon C, McLeod B. Audit of the frequency and clinical response to excessive oral anticoagulation in an out-patient population. Am J Hematol. 1998;59:22–27. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8652(199809)59:1<22::AID-AJH5>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Meer FJ, Rosendaal FR, Vandenbroucke JP, Briët E. Bleeding complications in oral anticoagulant therapy. An analysis of risk factors. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1557–1562. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410130073007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hylek EM, Chang Y, Skates SJ, Hughes RA, Singer DE. Prospective study of the outcomes of ambulatory patients with excessive warfarin anticoagulation. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1612–1617. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azar AJ, Cannegieter SC, Deckers JW, Briet E, van Bergen PF, Jonker JJ, et al. Optimal intensity of oral anticoagulant therapy after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1349–1355. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The European atrial fibrillation trial study group (1995) Optimal oral anticoagulant therapy in patients with nonrheumatic atrial fibrillation and recent cerebral ischemia. N Engl J Med 333:5–10 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Murphy PT, Casey MC, Abrams K. Audit of patients on oral anticoagulants with international normalized ratios of eight or above. Clin Lab Haem. 1998;20:253–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.1998.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]