Abstract

Background/Aims

Anisakiasis is frequent in Jeju Island because of the people's habit of ingesting raw fish. This study evaluated the clinical characteristics of patients with small bowel anisakiasis and compared them with those of patients with gastric anisakiasis.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 109 patients diagnosed with anisakiasis between May 2003 and November 2011.

Results

Of the 109 patients diagnosed with anisakiasis, those with suspicious anisakiasis (n=38) or possible anisakiasis (n=12) were excluded. The age and gender distributions did not differ between patients with small bowel anisakiasis (n=30; age, 45±13 years) and those with gastric anisakiasis (n=29; age, 46±10 years). The mean duration of hospitalization was 5.4±4.3 days for patients with small bowel anisakiasis and 0.5±1.7 days for patients with gastric anisakiasis. Small bowel anisakiasis was accompanied by leukocytosis (76.7% vs 25.5%, p=0.003) and elevated C-reactive protein levels (3.4±3.2 mg/dL vs 0.5±0.3 mg/dL, p=0.009). Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography showed small bowel wall thickening with dilatation in 93.3% (28/30) of patients and a small amount of ascites in 80.0% (24/30) of patients with small bowel anisakiasis.

Conclusions

Compared with gastric anisakiasis patients, small bowel anisakiasis patients had a longer hospitalization time, higher inflammatory marker levels, and small bowel wall thickening with ascites.

Keywords: Anisakiasis, Small intestine, Stomach, Characteristics

INTRODUCTION

Anisakiasis can be caused by Anisakis simplex, Anisakis physeteris, or Pseudoterranova species, which are zoonotic round worms that have marine mammals as their natural hosts.1,2 Anisakiasis occurs in several countries but is most common in Japan, probably because of the frequent ingestion of raw fish. Gastric anisakiasis accounts for the vast majority of reported cases of anisakiasis, whereas small bowel anisakiasis occurs infrequently. Most symptoms associated with anisakiasis are caused by either an allergic reaction or direct tissue damage resulting from invasion of the gut wall.3 Gastric anisakiasis usually develops from 1 to 8 hours after ingestion of raw fish, whereas small bowel anisakiasis may take up to a few days.4 Acute abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and pyrexia are the major clinical symptoms, and a history of ingesting raw fish is helpful when diagnosing a complaint of acute abdominal pain after food ingestion.4,5 Gastric anisakiasis is easily diagnosed by direct gastroscopic examination of an ulcerated bleeding lesion, which may show A. simplex on the surface of the stomach, or by barium studies, which may show a thread-like filling defect suggesting the presence of a worm within the stomach.6,7

There are only a few reports on small bowel anisakiasis in Japan8-10 and Korea.5,11,12 Japanese food such as sashimi and sushi is also popular in the United States, and a case of small bowel anisakiasis after ingesting raw fish has been reported in the United States.13 To our knowledge, there are few reports on the clinical characteristics of small bowel anisakiasis. Anisakiasis occurs more frequently in Jeju Island than in other regions in Korea because the residents of the island ingest raw fish more frequently. This study was conducted to analyze the clinical characteristics of patients with small bowel anisakiasis compared with those of gastric anisakiasis in Jeju Island.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

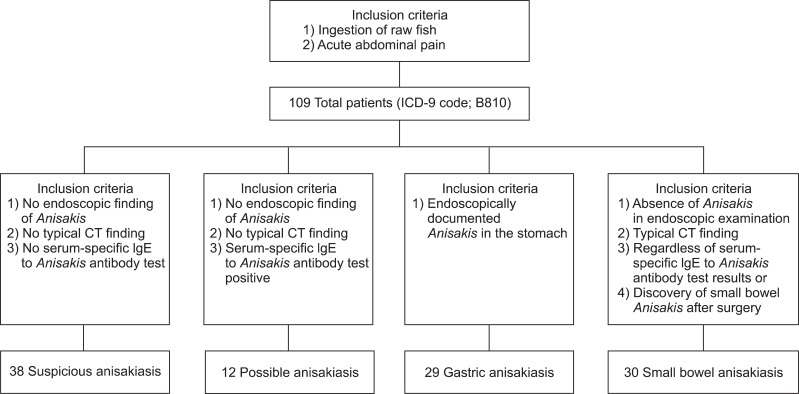

We conducted a retrospective study of eligible adult patients diagnosed with anisakiasis according to the International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision (ICD-9 code; B810) between May 2003 and November 2011. All data were collected in a single center, Jeju National University Hospital. All patients who complained of acute abdominal pain after ingesting raw fish were classified as having suspicious, possible, confirmed gastric, or small bowel anisakiasis depending on the diagnostic criteria shown in Fig. 1. Patients diagnosed with small bowel anisakiasis were included in the study if they met all the following diagnostic criteria: absence of anisakiasis in gastroscopic examination and the presence of concentric thickening of the small bowel wall with or without ascites on contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) regardless of the level of serum-specific immunoglobulin E (IgE) to A. simplex. We analyzed the clinical characteristics, laboratory test results, and radiological findings in the small bowel and gastric anisakiasis groups but excluded patients with suspicious or possible anisakiasis because of poor medical records.

Fig. 1.

Overview of eligible adult patients and diagnostic criteria for anisakiasis. Typical computed tomography (CT) findings: 1) concentric bowel wall thickening or a target sign and 2) ascites.

IgE, immunoglobulin E.

2. Clinical characteristics

The ingested raw fish were classified into three categories: sashimi, sushi, and others. The time interval between ingesting the raw fish and the onset of clinical symptom was assessed. The season was classified as spring (March to May), summer (June to August), autumn (September to November), and winter (December to February). Clinical symptoms including abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever were investigated. The mean duration of hospitalization was recorded for all patients.

3. Laboratory findings

The number of leukocytes and eosinophils, and C-reactive protein (CRP) level were measured. Leukocytosis was defined as a white blood cell count ≥10,000/mm3. Eosinophilia was defined as an eosinophil count ≥500/mm3 at admission. The level of serum-specific IgE to A. simplex was measured using the ImmunoCAP assay (Phadia AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Levels >0.35 kU/L were considered positive. Immunological test results were graded as follows: 0+(<0.35 kU/L), 1+(0.35 to 0.69 kU/L), 2+(0.70 to 3.49 kU/L), 3+(3.50 to 17.49 kU/L), 4+(17.50 to 49.99 kU/L), 5+(50.00 to 100 kU/L), and 6+(>100 kU/L).

4. Radiological findings

Plain abdominal radiography and contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT were performed. We investigated the presence of ileus in plain abdominal radiographs and the presence of concentric thickening of the small bowel wall, ascites, and/or strangulation shown by contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic CT.

5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test, chi-square test, and linear-by-linear association. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean±standard deviation. We analyzed age, sex, season, kinds of ingested food, clinical symptoms, and time variables including the interval from ingestion of raw fish to the onset of clinical symptoms and the duration of hospitalization. The data were analyzed using SPSS version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and p<0.05 was considered significant.

6. Ethics statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jeju National University Hospital approved the study protocol (IRB No. 2011-82). Written informed consent was not required because this was a retrospective chart-review study.

RESULTS

1. Clinical characteristics of the patients

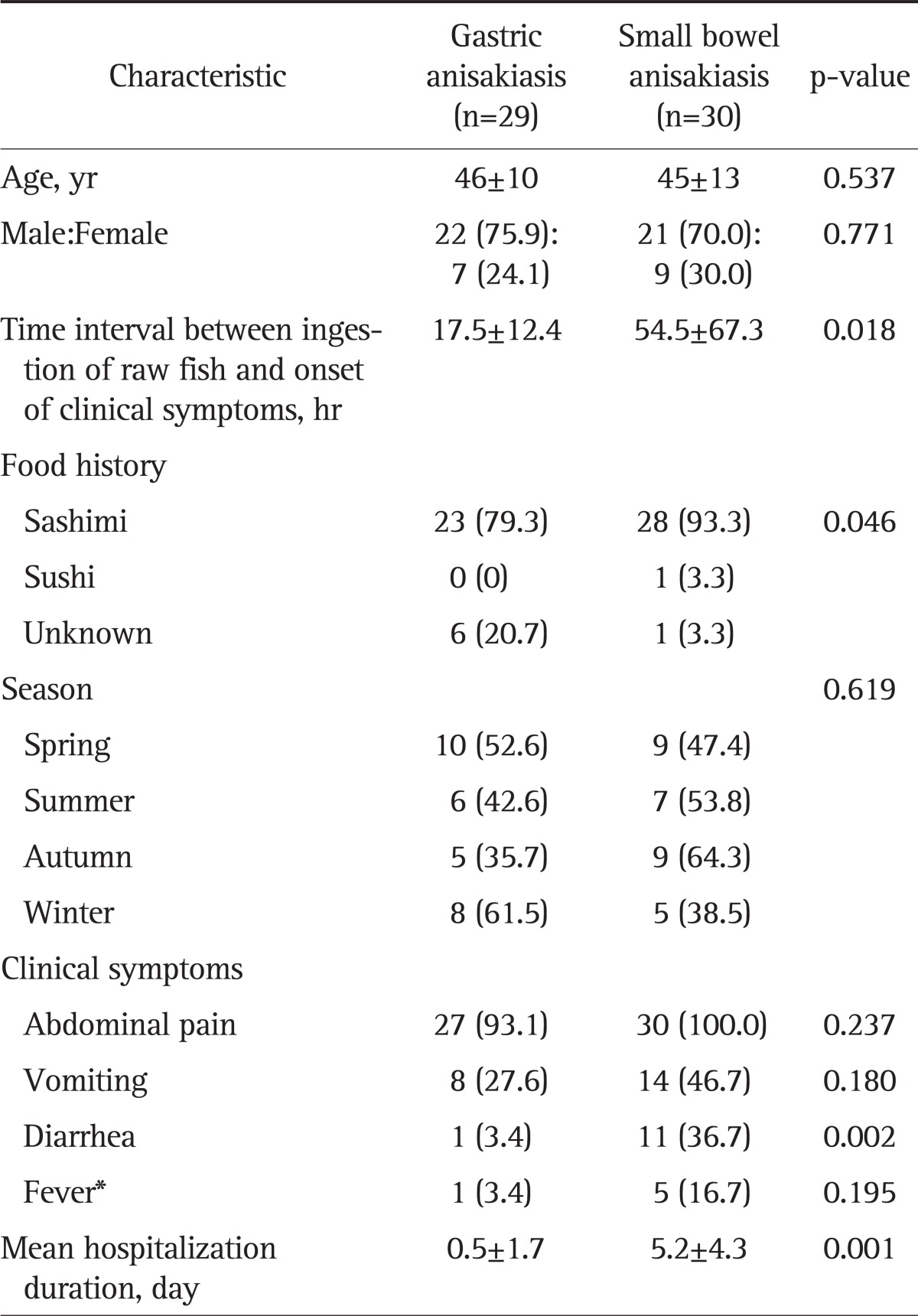

We evaluated a total of 109 eligible adults who complained of acute abdominal pain after ingesting raw fish. The patients were classified into four groups according to the diagnostic criteria shown in Fig. 1: suspicious anisakiasis in 38 patients (34.9%), possible anisakiasis in 12 patients (11.0%), gastric anisakiasis in 29 patients (26.6%), and small bowel anisakiasis in 30 patients (27.5%). Of these patients, only one patient was treated surgically, and small bowel anisakiasis was identified by the discovery of anisakiasis after surgery. The demographic characteristics of patients with gastric and small bowel anisakiasis are shown in Table 1. Age and sex distribution did not differ between the small bowel anisakiasis (n=30; age, 45±13 years) and gastric anisakiasis (n=29; age, 46±10 years) groups. However, the time interval between ingestion of raw fish and the onset of clinical symptoms was longer in the small bowel anisakiasis group than in the gastric anisakiasis group (54.5±67.3 hours vs 17.5±12.4 hours, p=0.018). Most patients ate sashimi (93.3% in the small bowel anisakiasis group vs. 79.3% in the gastric anisakiasis group). There was no seasonal variability. The most common manifestation of small bowel anisakiasis was abdominal pain (100.0%), followed by vomiting (46.7%), diarrhea (36.7%), and fever (16.7%). Diarrhea was the predominant symptom of small bowel anisakiasis compared with the prevalence of diarrhea in gastric anisakiasis (36.7% vs 3.4%, respectively; p=0.002). The mean duration of hospitalization for small bowel anisakiasis and gastric anisakiasis was 5.4±4.3 and 0.5±1.7 days, respectively.

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Gastric versus Those of Patients with Small Bowel Anisakiasis

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

*Fever was defined as a body temperature >37.8℃ measured from the tympanic membrane.

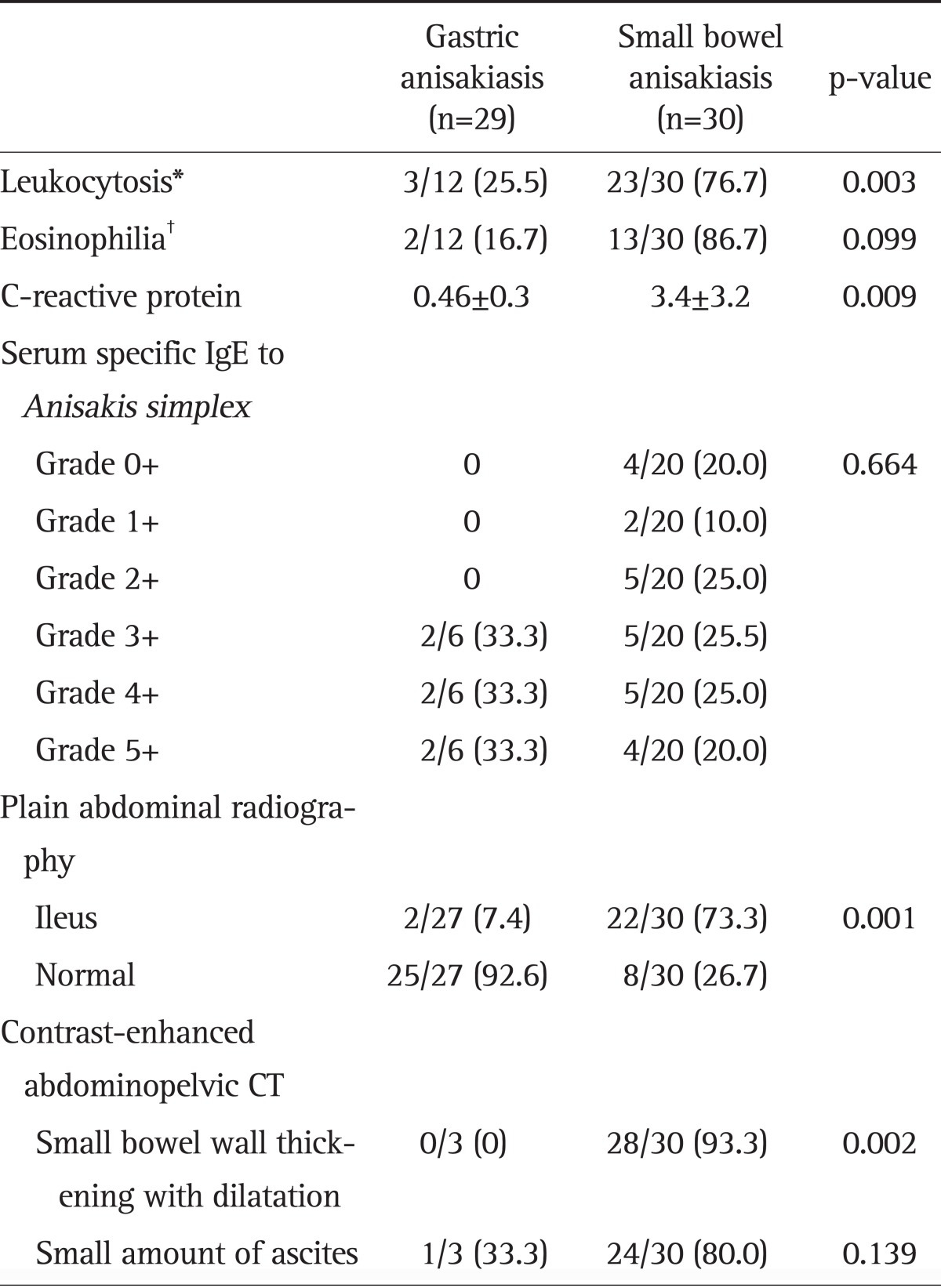

2. Laboratory findings

The laboratory and CT findings are shown in Table 2. Compared with gastric anisakiasis, a higher percentage of patients with small bowel anisakiasis exhibited leukocytosis (76.7% vs 25.5%, p=0.003), eosinophilia (86.7% vs 16.7%, p=0.099), and elevated CRP level (3.4±3.2 mg/dL vs 0.5±0.3 mg/dL, p=0.009). The findings of the Anisakis-specific antibody tests are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of Laboratory and CT Findings in Gastric and Small Bowel Anisakiasis Patients

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

IgE, immunoglobulin E; CT, computed tomography.

*Leukocytosis was defined as a white blood cell count ≥10,000/mm3; †Eosinophilia was defined as an eosinophil count ≥500/mm3.

3. Radiological findings

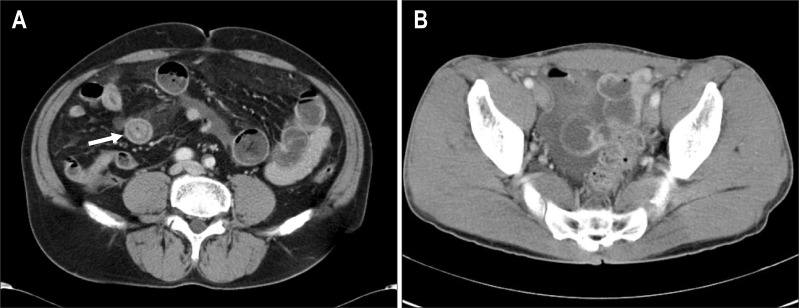

Plain supine and erect abdomen X-rays showed mild small bowel ileus, including dilatated small bowel loops with air-fluid levels, which was more common in small bowel anisakiasis than in gastric anisakiasis (73.3% vs 7.4%, p=0.001) (Table 2). Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT imaging showed diffuse small bowel wall thickening with proximal bowel dilatation in 28 (93.3%) of all patients, and small amounts of ascites were observed in 24 (80.0%) of patients with small bowel anisakiasis (Table 2). There was a long segmental concentric wall thickening of the proximal ileum with dilatation of the jejunum, which raised suspicion of small bowel anisakiasis in contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic CT (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Small bowel anisakiasis involving the right lower quadrant of the ileum. (A) A contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) image through the mid-abdominal level showing diffuse concentric small bowel wall thickening with a target sign (arrow) and proximal small bowel dilatation. (B) A contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic CT image through the pelvis showing a small amount of ascites in the pelvic cavity.

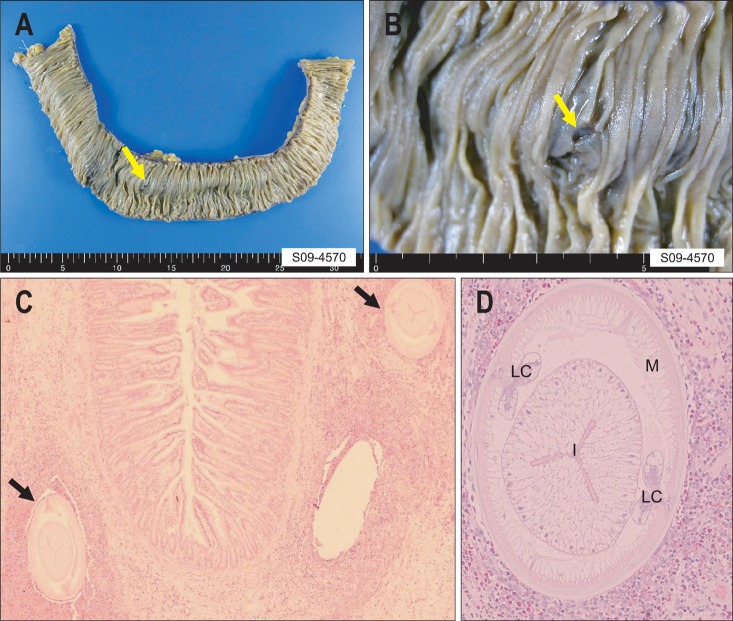

4. Pathological findings

Only one patient underwent surgery because of small bowel obstruction, and this patient had no definite history of eating raw fish. This patient was diagnosed pathologically with small bowel anisakiasis after surgery, and the whole body of a live A. simplex was found in the excised small bowel specimen. The gross examinations of the specimens from the diseased bowel revealed the penetration of A. simplex into the bowel wall (Fig. 3A and B). Histopathological examination revealed two larvae surrounded by a thick cuff of acute inflammatory cells with numerous eosinophils in cross sections (Fig. 3C). High magnification of a cross section of a larva revealed a thin external cuticle with no lateral alae, celomyarian and polymyarian muscle layers, prominent Y-shaped lateral chords, an intestine with a single layer of columnar epithelium, and no apparent reproductive system (Fig. 3D). These internal structures of the larvae are pathognomonic for A. simplex.13

Fig. 3.

Small bowel segmental resection in a patient with small bowel anisakiasis. (A, B) The resected small bowel specimen (approximately 30 cm) showing the penetration of an Anisakis larva into the bowel wall (yellow arrow). (C) H&E-stained cross section showing two larvae (black arrows) surrounded by a thick cuff of acute inflammatory cells with numerous eosinophils (×200). (D) High-power view of a cross section through a larva (H&E stain, ×400).

M, muscle layer; LC, lateral chord; I, intestine.

DISCUSSION

A. simplex can infest humans and can cause anisakiasis through the ingestion of raw fish. Acute anisakiasis is probably caused by a type I and/or type III allergic reaction to digestive tract mucus and presents as abdominal pain and eosinophilic infiltration.14 Chronic anisakiasis can cause abscess or eosinophilic granulomas.14 The first case of anisakiasis was reported in the Netherlands by van Thiel et al.15 in 1960. The incidence of anisakiasis has increased recently because of the frequent ingestion of raw fish. Anisakiasis is most common in Japan, where >2,000 cases occur every year, accounting for 95% of the total worldwide cases.8,16 In Europe and the United States, the number of clinical reports has increased rapidly because of increasing popularity of ingesting raw fish. The number of reported cases is increasing although the true number of cases of enteric anisakiasis is probably greater than that reported.

Several uncooked seafood dishes can be sources of the pathogen including Japanese sashimi and sushi, Peruvian ceviche, and Hawaiian lomi-lomi. Other potential sources are insufficiently salted or pickled fish such as Dutch or German green herring, Spanish boquerones en vinagre, and Italian alici marinate.17 Anisakiasis is a relatively common infectious disease in areas where such foods are consumed. In this study, 52/59 (88.1%) of patients with gastric or small bowel anisakiasis ingested raw fish, but because of the limitations of a retrospective study it was uncertain whether the other seven (11.9%) had ingested raw fish. Anisakiasis is most common in Jeju Island in Korea because most people in this area eat raw fish frequently. Clinical manifestations include sudden and violent abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and fever, similar to those of acute abdominal syndrome, as exhibited by our patients. It is important for the clinician to suspect anisakiasis in patients with such symptoms to avoid misdiagnosis.

Endoscopic diagnosis of small bowel anisakiasis can be difficult, but the diagnosis can be established using barium series, abdominal ultrasonography, enhanced abdomino-pelvic CT, serum IgE levels, and skin tests using A. simplex extracts.14,18,19 Leukocytosis without eosinophilia is a common laboratory finding in this condition20 and may lead to an incorrect diagnosis of acute appendicitis or regional enteritis.21 In our study, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and CRP levels were significantly greater in patients with small bowel anisakiasis than in those with gastric anisakiasis, although the data were limited in gastric anisakiasis patients. Our findings suggest that both leukocytosis and eosinophilia may be helpful in diagnosing small bowel anisakiasis. However, a previous report showed that testing for eosinophilia alone may not help to diagnose or rule out small bowel anisakiasis.19

An elevated titer of anti-Anisakis antibodies in blood is sensitive (100%) but not very specific (50%)19,22 because of cross-reactions with proteins in other parasites (Ascaris, Toxocara, and Echinococcus), microorganisms, insects, and plants.23 The measurement of anti-Anisakis antibody titer may take a long time and the titer may not be elevated in the early phase after the onset of symptoms.19 Healthy individuals who eat raw fish regularly may exhibit a pseudopositive reaction. Therefore, the diagnosis of anisakiasis is difficult to make solely on the basis of the anti-Anisakis antibody titer in emergency situations.10,19 In this study, four of 20 patients (20.0%) with small bowel anisakiasis had a negative anti-Anisakis antibody titer probably because they were in the acute phase. When an accurate diagnosis must be established quickly, serological testing is important for chronic anisakiasis, although the test is not useful in the acute state.18 We did not measure total IgE titer, but A. simplex-specific IgE has been shown to be helpful in the diagnosis of anisakiasis.

Radiological examination is important in the diagnosis of acute small bowel anisakiasis. In our study, plain abdominal radiographs revealed findings consistent with ileus, such as dilated small bowel loops with air-fluid levels in 7.4% of patients with gastric anisakiasis and in 73.3% of patients with small bowel anisakiasis. The presence of ileus differs significantly, and this may provide a clue in the diagnosis of small bowel anisakiasis.19 As reported previously,5,9,24 transient and segmental thickening of the small bowel wall and the presence of ascites suggest the possibility of intestinal anisakiasis in patients who complain of abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced abdominopelvic CT provides more accurate information about the bowel involvement including the location, length, severity, mesenteric changes, and severity of small bowel obstruction. Contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic CT in combination with the detection of serum Anisakis-specific IgE is useful for the diagnosis of enteric anisakiasis.9

Surgery must not be performed in a patient with small bowel anisakiasis unless there are serious complications such as small bowel obstruction. Most patients with small bowel anisakiasis improve with conservative treatment, and unnecessary surgical treatment should be avoided.25 A laparotomy or laparoscopic surgery should be considered when strangulation, obstruction, volvulus, or severe long-segment small bowel stenosis is suspected.26,27 Eosinophilic granuloma may cause a strangulating intestinal obstruction.8,26 Intestinal obstruction can be treated with early administration of parenteral corticosteroid, which will help avoid the need for excision of the small intestine.28 The best treatment for anisakiasis is prophylaxis.14 People should not ingest raw mackerel or cod from sea areas where many marine mammals live.8 Early evisceration is recommended because the worms leave the digestive tract within a few days and migrate to the muscles. In addition, freezing the fish at -20℃ for 3 days or heating to 70℃ can kill the larvae because they can survive only to 50℃.6,14

Our study showed that small bowel anisakiasis is as prevalent as gastric anisakiasis in Jeju Island because people in this area enjoy eating raw fish. Jeju Island is unique in Korea because the residents eat raw fish often similar to Japanese. Most anisakiasis patients experience a self-limiting clinical course with conservative treatment alone. However, unlike gastric anisakiasis, small bowel anisakiasis has a longer hospitalization and interval between the ingestion of raw fish and the onset of clinical symptom than in gastric anisakiasis. Clinicians should suspect small bowel anisakiasis rather than gastric anisakiasis in patients with acute abdominal pain after eating raw fish if there is a longer interval (from a few days to weeks) between the ingestion of raw fish and the onset of clinical symptom, diarrhea is the predominant symptom, and the patient requires longer hospitalization, has increased inflammatory marker levels, and imaging shows small bowel wall thickening with ascites. The diagnosis of small bowel anisakiasis requires a thorough history of eating raw fish and clinical, laboratory, and radiological test findings.

However, this study has a few limitations. First, it is a retrospective cohort study of patients in Jeju Island who had possible clinical radiological and biochemical differences between small bowel and gastric anisakiasis. The criteria of small bowel anisiakiasis is absence of gastric infection and presence of small bowel thickening at the CT scan, irrespective to the presence of positivity to serum-specific IgE to A. simplex. With this diagnostic criteria, any stricture of small bowel associated to abdominal pain such as vasculitis or Crohn's disease could be misdiagnosed as small bowel anisakiasis. Actually, pathologically proven small bowel aniskiasis was just one case in our study. Secondly, the studies needed for inclusion were incomplete due to retrospective design of this study. Ideally, all the patients should undergo upper GI endoscopy with histology, abdominopelvic CT scan and serum specific IgE to A. simplex.

In conclusion, this study has value as the first study to compare the clinical characteristics of small bowel and gastric anisakiasis in Jeju Island. These two conditions differ in terms of the interval between the ingestion of raw fish and the appearance of symptoms, main symptoms, inflammatory marker levels, and length of hospitalization.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the research grant of the Jeju National University in 2009.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Audicana MT, Kennedy MW. Anisakis simplex: from obscure infectious worm to inducer of immune hypersensitivity. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:360–379. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochberg NS, Hamer DH. Anisakidosis: perils of the deep. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:806–812. doi: 10.1086/656238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caramello P, Vitali A, Canta F, et al. Intestinal localization of anisakiasis manifested as acute abdomen. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:734–737. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park MS, Kim KW, Ha HK, Lee DH. Intestinal parasitic infection. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:166–171. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9324-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon SW, Yu JS, Park MS, Shim JY, Kim HJ, Kim KW. CT findings of surgically verified acute invasive small bowel anisakiasis resulting in small bowel obstruction. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:739–742. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.4.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakata H, Takeda K, Nakayama T. Radiological diagnosis of acute gastric anisakiasis. Radiology. 1980;135:49–53. doi: 10.1148/radiology.135.1.7360979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouree P, Paugam A, Petithory JC. Anisakidosis: report of 25 cases and review of the literature. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;18:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(95)98848-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takabe K, Ohki S, Kunihiro O, et al. Anisakidosis: a cause of intestinal obstruction from eating sushi. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1172–1173. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe T, Ohta S, Iwamoto S, et al. Small bowel anisakiasis with self-limiting clinical course. Intern Med. 2008;47:2191–2192. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sasaki T, Fukumori D, Matsumoto H, Ohmori H, Yamamoto F. Small bowel obstruction caused by anisakiasis of the small intestine: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:123–125. doi: 10.1007/s005950300027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CM, Choi JY, Kim JH. Intestinal obstruction caused by anisakiasis. J Korean Surg Soc. 2008;74:154–156. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang DB, Oh JT, Park WC, Lee JK. Small bowel obstruction caused by acute invasive enteric anisakiasis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2010;56:192–195. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2010.56.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takei H, Powell SZ. Intestinal anisakidosis (anisakiosis) Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:350–352. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno-Ancillo A, Caballero MT, Cabañas R, et al. Allergic reactions to Anisakis simplex parasitizing seafood. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1997;79:246–250. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Thiel P, Kuipers FC, Roskam RT. A nematode parasitic to herring, causing acute abdominal syndromes in man. Trop Geogr Med. 1960;12:97–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagei N, Orikasa H, Hori E, Sannomiya A, Yasumura Y. A case of hepatic anisakiasis with a literal survey for extra-gastrointestinal anisakiasis. Kisechugaku Zasshi. 1995;44:346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Kuwabara K, Hashimoto H, Matsuda S. Clinical features of bowel anisakiasis in Japan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:104–105. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.García M, Moneo I, Audicana MT, et al. The use of IgE immunoblotting as a diagnostic tool in Anisakis simplex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:497–501. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ido K, Yuasa H, Ide M, Kimura K, Toshimitsu K, Suzuki T. Sonographic diagnosis of small intestinal anisakiasis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1998;26:125–130. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0096(199803/04)26:3<125::aid-jcu3>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park SH, Suh JM, Shim KS, Baeg NJ, Kim BS, Moon IS. A case report of intestinal anisakiasis. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;10:373–375. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimachi K, Inokuchi K, Ooiwa T, Fujino T, Ishii Y. Acute gastric anisakiasis. Analysis of 178 cases. JAMA. 1985;253:1012–1013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakanari JA, Loinaz HM, Deardorff TL, Raybourne RB, McKerrow JH, Frierson JG. Intestinal anisakiasis: a case diagnosed by morphologic and immunologic methods. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;90:107–113. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/90.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lorenzo S, Iglesias R, Leiro J, et al. Usefulness of currently available methods for the diagnosis of Anisakis simplex allergy. Allergy. 2000;55:627–633. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim WK, Song SY, Cho OK, et al. CT findings of small bowel anisakiasis: analysis of four cases. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2011;64:167–171. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishida M, Harada A, Egawa S, Watabe S, Ebina N, Unno M. Three successive cases of enteric anisakiasis. Dig Surg. 2007;24:228–231. doi: 10.1159/000103325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masui N, Fujima N, Hasegawa T, et al. Small bowel strangulation caused by parasitic peritoneal strand. Pathol Int. 2006;56:345–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsuo S, Azuma T, Susumu S, Yamaguchi S, Obata S, Hayashi T. Small bowel anisakiosis: a report of two cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4106–4108. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i25.4106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos L, Alonso C, Guilarte M, Vilaseca J, Santos J, Malagelada JR. Anisakis simplex-induced small bowel obstruction after fish ingestion: preliminary evidence for response to parenteral corticosteroids. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:667–671. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]