Abstract

Background/Aims

To asses the usefulness of flexible metallic stents in the palliation of malignant obstruction of gastric outlet and duodenum.

Methods

Retrospective review was performed between January 2006 and December 2011 in 30 patients. Thirty consecutive patients with obstruction of the gastric outlet underwent palliative treatment with self-expandable flexible metallic stents. Complications and clinical outcomes were assessed.

Results

Twenty-four patients had advanced gastric carcinoma at the antrum and/or pylorus, four patients had obstruction at the pylorus due to pancreas tumours and one patient had duodedum and one patient had gall bladder tumour. Symptoms improved in 82.7% of the patients after the procedure. The improvement in ability to eat using the score system was statistically significant (p<0.001). Tumor ingrowth and/or overgrowth were seen in four patients (13.3%), and a second stent was inserted in these patients. The mean stent patency was 100 days (range, 5 to 410). The mean survival was 120.76±38.96 days.

Conclusions

Endoscopic placement of self-expendable metallic stents under fluoroscopy is a safe and effective treatment for the palliation of patients with inoperable malignant gastric outlet obstruction caused by stomach or pancreas cancer.

Keywords: Gastric outlet obstruction, Self expendable metallic stents, Advanced malignancies

INTRODUCTION

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is the most common complication of advanced distal gastric, periampullary, or duodenal malignancy. The majority of cases have locally advanced or metastatic cancer, with poor prognosis and a median survival of 3 to 6 months.1,2 They often suffer from intractable nausea, vomiting, and severe weight loss. Traditionally, the only therapeutic strategy was surgical gastroenterostomy. However surgical palliation caries a relatively high risk of mortality and morbidity, and is associated with poor outcomes with persistent symptoms, delayed symptom relief, and prolonged hospital stay.3,4

Endoscopic placement of self-expendable metallic stents (SEMSs) has been used for palliative treatment of patients with malignant obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract for over a decade.5 The availability of enteral stents has allowed their deployment in gastroduodenal obstruction. Placement of SEMS is associated with higher clinical succes rates, less morbidity, less time to start oral intake, lower rates of delayed gastric emptying and a shorter hospital stay than palliative surgery. Here we report our experience in the treatment of gastric and duodenal obstruction using SEMS in recent years. We also discuss our opinions on the placement technique, indications, complications and follow-up results.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

A total of 30 consecutive patients underwent fluoroscopically guided endoscopic placement of through the scope (TTS) endoprosthesis to great gastroduodenal obstructions from January 2006 to May 2011. They all presented with severe nause and recurrent vomiting. Only the patients who had inoperable disease or were unsuitable for surgery because of the presence of significant comorbid conditions were selected for stent placement.

Data were collected from a variety of sources including patient charts, endoscopic procedure reports, radiological records and through a standardized questionnaire administered over the phone to patients and/or family members. Collected data included demographic information, underlying diagnosis, site of obstruction, number and type of stents used, as well as the technical success, and procedure and stent related complication rate. A scoring system similar to that used for the assessment of swallowing in patients with malignant dysphagia was constructed to assess the level of oral intake before and after the procedure.6 The GOO scoring system (GOOSS) assigns a point score depending on the patients' level of oral intake.7 The improvement in oral intake was evaluated as the best degree at least 3 days after stent insertion.

Placement of the stent

Before stent insertion, the degree, the nature and the site of the obstruction was assessed by using conventional forward-viewing gastroscope; an assessment was made of the length of stricture. When billiary obstruction was suspected, based on liver function tests and ultrasonography or computed tomography scan, endoscopic biliary stenting was attempted before gastric outlet stenting. Informed consent was obtained from all pateints before procedures. The procedures were performed under conscious sedation using a combination of intravenous midazolam and pethidine. All procedures were performed using endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance. Stents were inserted with a therapeutic endoscope with a working channel large enough (4.2 mm) to perform stenting. Both the covered and uncovered stents were made based on the characteristics of the lesion and operator's experience. The stents used in this study were SEMS (NITI-S, Pyloric [TTS]; Taewong, Seoul, Korea). The sizes of the stents were 18 to 20 mm in diameter and 60 to 120 mm in lenght. These stents are constructed from a nickel-titanium alloy with or without an outer membrane. After identification of the stenosis, a guidewire was passed through the stenosis using a standart endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter. Position of the catheter in the poststenotic area was checked with a contrast injection. The length of the stents used were based on the length of the stricture, with the intent that at least 2 cm of additional stent length was on each side of the stricture. An undeployed SEMS delivery system was passed through the working channel of the endoscope over the guidewire so that both the ends of the undeployed stent were equidistant from the ends of the stenosis. The stent was deployed from the distal end with a frequent repositioning of the proximal position in the desired location because of a tendency for it to move away from the stricture. After stent deployment, an immediate contrast flush was used to assess position and patency. A balloon dilatation was performed before stenting when the stent assembly could not pass the stenosis. We also performed a balloon dilation after stent deployment in four of our patients to get better stent expansion. The patients were monitored hourly for at least 8 hours after the procedure. If they did not complain of abdominal pain and the hemoglobin level was normal, they were allowed to resume oral intake of liquids. Their diet progressed to soft or semisolid foods when they could tolerate liquids well. A barium study or endoscopy was performed to verify the position and patency of the stent in cases of bad tolerance of foods or recurrence of nausea and vomiting.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were undertaken using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The values for the patients' baseline characteristics are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). GOOSS before and after stenting, was compared using the paired sample t-test. The catogarical data were examined using chi-squared test. The overall survival and stent patency were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier life table analysis. A p<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

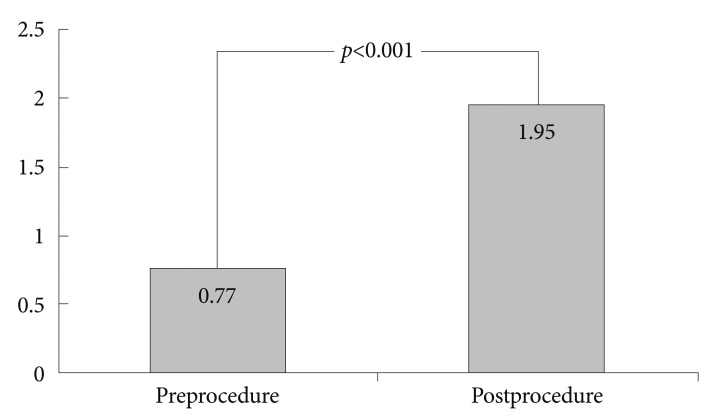

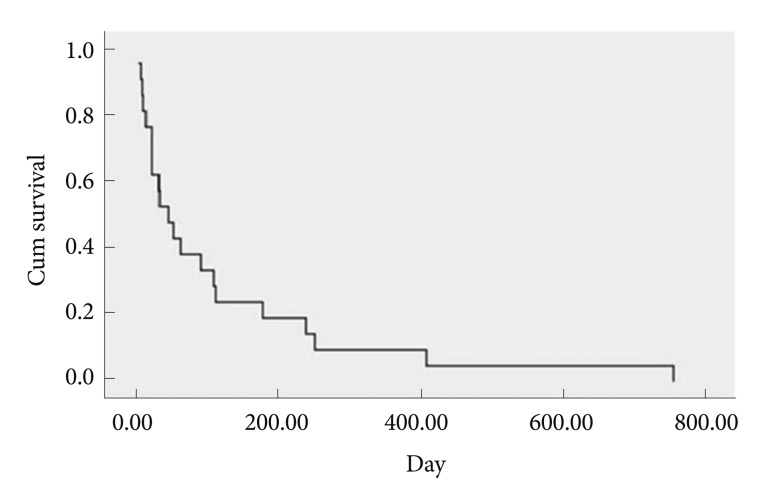

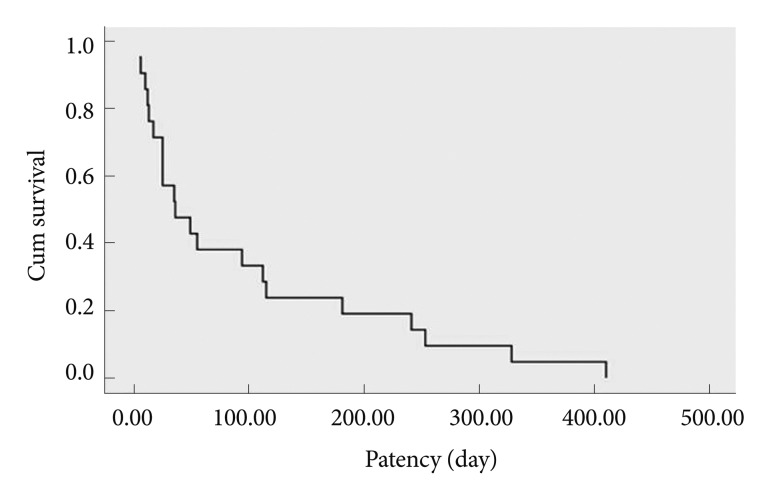

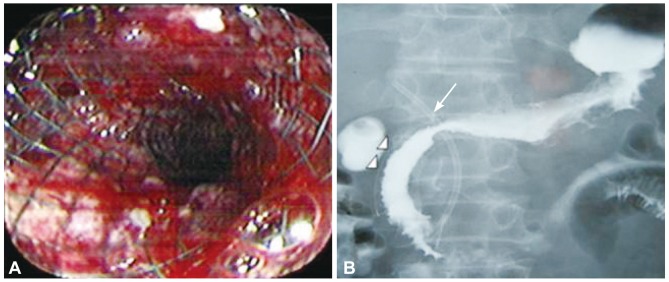

The 30 treated patients received a total of 34 stents. Mean patient age was 65.69±12.97 years. Eleven patients were females, the other 19 patients were males. Obstruction was caused by stomach cancer in 24 (80%), by pancreatic cancer in four (13.3%), by duodenal cancer in one (3.3%), and by gallbladder cancer in one (3.3%) patient. Stents implantation was succesfull in all patients. Ten patients received stricture dilatation before stent deployment. Symptoms improved in 25 (83.3%) patients after the procedure. There was no change in symptoms in four patients. Oral intake worsened in one patient. GOOSS improved significantly from a mean±SD of 0.77±0.42 before stent placement to mean±SD of 1.95±0.89 afterward (p<0.001) (Fig. 1). Post-stenting dilatation was performed on four of the patients since the stent was not adequately expanded. No immediate stent related complications were noted. There were no significant bleeding episodes related to stent insertion. The overall complication rate in our patients was 16.6%. Duodenal perforation developed in one (3.3%) patient at 7th day. Tumor ingrowth or/and overgrowth were seen in four patients (13.3%). Tumor ingrowth was detected in two (6.6%) patients at day 36 and day 328 and overgrowth was observed in one patient at day 94, both ingrowth and overgrowth was observed in one patient at day 112 after stenting. Restening was performed on four patients. Three patients developed malignant biliary obstruction in addition to GOO (Fig. 2). Two of these patients had pancreatic cancer and one had duodenal cancer. Prestent ERCP procedure was carried out on three patients. At the time when follow-up was ended, 22 patients had died and eight patients were alive. The mean survival was 120.76±38.96 days (Fig. 3). The mean stent patency time was 100 days (range, 5 to 410) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

Graphic shows gastric outlet obstruction scoring system of patients before and after stenting.

Fig. 2.

Gastric stent images. (A) Proximal view of an opened stent after stenting. (B) Radiographic image after combined endoscopic biliary (thin arrow) and duodenal (arrow head) stenting for nonsurgical treatment of malignant biliary obstruction and malignant gastric outlet obstruction in a patient with pancreatic cancer.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan Meier curve of patient survival after stent insertion.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan Meier curve of stent patency.

DISCUSSION

GOO is a preterminal event in patients with advanced malignancies of the stomach, pancreas, and duodenum. If left untreated, patients are unable to take oral nutrition, require nasogastric tube insertion and rapidly deteriorate. The patients tend to be poor surgical candidates because of their advanced stage and associated malnutrition. In recent years, SEMSs have provided an attractive alternative to surgery for palliative treatment of GOO. Our results suggest that endoscopic SEMS insertion is effective in the palliative treatment of GOO due to gastric, pancreatic, and duodenal cancer and the present study adds to mounting evidence that SEMS is effective in relieving malignant GOO with low mortality.

Several studies have assessed the clinical and technical success of endoscopic gastric outlet stenting in the palliative treatment of advanced distal stomach, periampulary, or duodenal cancer. It was reported that the technical success (placement of the stent itself) occured in 94% of patients and clinical success (improvement in oral intake) was achieved in 80% to 95% of pateints after stent placement.8-10 Although not a curative procedure, there is an excellent palliation of symptoms allowing the return to soft or semi-solid diet in the vast majorty of patients. Technical success rates depend on the site of the lesions. Complicated anatomy, severe stenosis or acute angulation of a duodenal loop may result in technical failure.11 After stent placement some patients may not show improvement in symptoms due to unrecognized distal small bowel strictures, lack of propulsive peristalsis in a chronically obstructed stomach, or functional GOO due to neural involvement of the tumor.12,13 In our series, technical success was achieved in all of these 30 patients (100%). On the other hand, clinical success was achieved in 24 patients (80.0%).

Expendable metallic stents can be placed with a fluoroscopic guidence, endoscopic guidence, or a comibination of both. The reported technical success rate with fluoroscopy is the same as that with endoscopy. In some cases, insertion under fluoroscopy is successful after failed endoscopic procedures, or vice versa.14 Fluoroscopy allows identification of contrast dye to delineate the stricture, defining its length and geometry, both of which greatly aid in the selection of stent type and size. Endoscopic guidance may reduce the procedure time by making guide-wire passage through the stenotic segment easier. We used both endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidence for stenting. The combination of endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance adds increased control, which facilitates both catheterization of stenosis and accurate device deployment.15

Adler and Baron7 introduced the GOOSS scale for grading the clinical degree of outlet obstruction both before and after treatment, and the scale is being increasingly adopted. A number of studies have demonstrated improved GOOSS results after stent replacement.9,16 Most patients can maintain oral intake until death from underlying cancer, which typically occurs within 4 months.7 We found a statistically significant improvement in the ability to eat in our patients, based on changes in the GOOSS. The present GOOSS findings are consistent with those in previous studies.

Stent patency can be influenced by the patient's demographic factors, underlying malignancy and stent type. Tumor ingrowth, overgrowth, and stent migration have been regarded as the main causes of patency loss of conventional uncovered or covered stents. Three studies concluded that chemotherapy was a prognostic factor for prolonged oral intake and stent patency.8,17,18 Chemotherapy may decrease the tumor size and the rate of tumor growth as well and hence it may promote the maximal stent expansion and prolong the stent patency. Significantly we found that the mean stent patency was 100 days, which is lower than the previously reported studies (146 to 385 days).18-22 Differences in stent patency may also arise because of different indications for stent placement.

Complication rates range from 11% to 43% and can be reported as immediate, which occur within the 24 hours after placement of SEMS, early or late.23-25 Immediate and early complications include problems with sedation, stent obstruction, stent malposition, perforation, aspiration, and bleeding. Late complications include stent obstruction, perforation, stent migration, and fistula formation. The overall complication rate in our patients was 16.6%, which is comparable to the levels seen in previous reports. Obstruction by tumor ingrowth and/or overgrowth was managed with the placement of additional covered stents through the original stent. In one patient, perforation secondary to the erosion in the duodenal loop caused by the distal end of the stent was detected at day 7 after the stenting. The patient with a verified perforation developed sepsis and died.

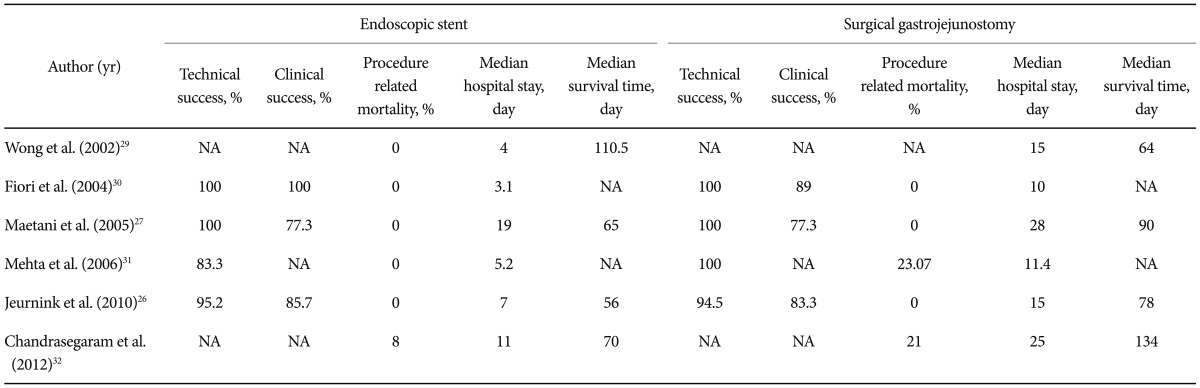

Traditionally, GOO is treated with a surgical gastrojejunostomy (SGJ). Jeurnink et al.26 reported that SGJ was associated with better long-term results and is therefore the treatment of choice in patients with life expentancy of 2 months or longer. Maetani et al.27 retrospectively reviewed the outcomes of 20 patients who underwent palliative enteral stenting compared with 19 matched pateints who underwent SGJ and found that endoscopical stenting group was significantly earlier to return back to an oral diet than the SGJ group. Rapid resumption of oral intake and less morbidity after stenting might lead to early hospital discharge and consequent cost effectiviness. Studies comparing SEMS and surgical gastroenterostomy confirmed that SEMS was associated with higher clinical success rate, a shorter time to starting oral intake, and a lower incidence of delayed gastric emptying than SGJ (Table 1).28-32 In our series, none of the patients was hospitalized and all of them started oral intake after the stenting.

Table 1.

Literature Review: Studies Comparing Endoscopic Stent and Surgical Gastrojejunostomy

NA, not available.

Almost 11% of the patients in our series developed biliary obstruction right in addition to gastroduodenal obstruction. On these patients we performed prestenting ERCP and biliary stenting. Biliary obstruction is a common problem among patients with GOO. It may occur before development of GOO, at the same time or after the release of the obstruction. In later occurring cases, it is very difficult to place biliary stents through the mesh of duodenal stents endoscopically and a percutaneous transhepatic approach is usually required.5,33 However, Mutignani et al.34 published a study in which they succeeded in placing a biliary stent throughout the meshes of duodenal stent using argon plasma coagulation. Based on this finding, it would seem prudent to consider a preliminary evaluation of the biliary tree in patients who are to undergo gastroduodenal stenting.

In previous clinical studies of gastric outlet stent placement mean survival ranged from 62 to 145 days.17,18,35,36 In our series, mean survival of patients is 120 days. No studies have shown any evidence of survival benefit associated with the relief of malignant obstruction. It has been shown that survival is influenced by the type and stage of the underlying disease, because GOO seems to be a later and more likely terminal event in pancreatic and biliary cancer than in gastric carcinoma,28 and patients with GOO caused by carcinomas arising from these sites may have a shorter life expectancy. Our investigation was a single-centre study in which 79.3% of patients had gastric malignancy. In most western reports, the most common primary illness related to GOO is pancreatic cancer and most gastric oulet obstruction develops in the terminal stage in patients with pancreatic or biliary cancer.

In conclusion, endoscopic stenting for the palliation of malignant GOO is feasible and well-tolerated in most patients. It restores functional status and gives good palliation to patients with a preterminal condition. Gastrojejunostomy should be preserved for cases in which endoscopic stenting is not succesful or possible.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bakkevold KE, Arnesjø B, Dahl O, Kambestad B. Adjuvant combination chemotherapy (AMF) following radical resection of carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater: results of a controlled, prospective, randomised multicentre study. Eur J Cancer. 1993;29A:698–703. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80349-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geer RJ, Brennan MF. Prognostic indicators for survival after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1993;165:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80406-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jung GS, Song HY, Kang SG, et al. Malignant gastroduodenal obstructions: treatment by means of a covered expandable metallic stent-initial experience. Radiology. 2000;216:758–763. doi: 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00au05758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujino Y, Suzuki Y, Kamigaki T, Mitsutsuji M, Kuroda Y. Evaluation of gastroenteric bypass for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:563–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baron TH, Harewood GC. Enteral self-expandable stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:421–433. doi: 10.1067/s0016-5107(03)00023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellow MH, Pinkas H. Endoscopic laser therapy for malignancies affecting the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction. Analysis of technical and functional efficacy. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:1443–1446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Song HY, Shin JH, et al. Metallic stent placement in the palliative treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstructions: prospective evaluation of results and factors influencing outcome in 213 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dormann A, Meisner S, Verin N, Wenk Lang A. Self-expanding metal stents for gastroduodenal malignancies: systematic review of their clinical effectiveness. Endoscopy. 2004;36:543–550. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay JO, Andreyev HJ, Vlavianos P, Westaby D. Self-expanding metal stents for the palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction in patients unsuitable for surgical bypass. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:901–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabharwal T, Irani FG, Adam A Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe. Quality assurance guidelines for placement of gastroduodenal stents. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0110-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bessoud B, de Baere T, Denys A, et al. Malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: palliation with self-expanding metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(2 Pt 1):247–253. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000145227.90754.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song HY, Yang DH, Kuh JH, Choi KC. Obstructing cancer of the gastric antrum: palliative treatment with covered metallic stents. Radiology. 1993;187:357–358. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.2.7682722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopera JE, Brazzini A, Gonzales A, Castaneda-Zuniga WR. Gastroduodenal stent placement: current status. Radiographics. 2004;24:1561–1573. doi: 10.1148/rg.246045033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mauro MA, Koehler RE, Baron TH. Advances in gastrointestinal intervention: the treatment of gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stents. Radiology. 2000;215:659–669. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.3.r00jn30659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piesman M, Kozarek RA, Brandabur JJ, et al. Improved oral intake after palliative duodenal stenting for malignant obstruction: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2404–2411. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho YK, Kim SW, Hur WH, et al. Clinical outcomes of self-expandable metal stent and prognostic factors for stent patency in gastric outlet obstruction caused by gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:668–674. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Telford JJ, Carr-Locke DL, Baron TH, et al. Palliation of patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction with the enteral Wallstent: outcomes from a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:916–920. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim JH, Song HY, Shin JH, et al. Metallic stent placement in the palliative treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstructions: primary gastric carcinoma versus pancreatic carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:241–247. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song HY, Kim TH, Choi EK, et al. Metallic stent placement in patients with recurrent cancer after gastrojejunostomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maire F, Hammel P, Ponsot P, et al. Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:735–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung GS, Song HY, Seo TS, et al. Malignant gastric outlet obstructions: treatment by means of coaxial placement of uncovered and covered expandable nitinol stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61720-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaidos JK, Draganov PV. Treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction with endoscopically placed self-expandable metal stents. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4365–4371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nassif T, Prat F, Meduri B, et al. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expandable metallic stents: results of a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2003;35:483–489. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masci E, Viale E, Mangiavillano B, et al. Enteral self-expandable metal stent for malignant luminal obstruction of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract: a prospective multicentric study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:389–394. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318033d30a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, et al. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:490–499. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maetani I, Tada T, Ukita T, Inoue H, Sakai Y, Nagao J. Comparison of duodenal stent placement with surgical gastrojejunostomy for palliation in patients with duodenal obstructions caused by pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Endoscopy. 2004;36:73–78. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosono S, Ohtani H, Arimoto Y, Kanamiya Y. Endoscopic stenting versus surgical gastroenterostomy for palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:283–290. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-2003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong YT, Brams DM, Munson L, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to pancreatic cancer: surgical vs endoscopic palliation. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:310–312. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fiori E, Lamazza A, Volpino P, et al. Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehta S, Hindmarsh A, Cheong E, et al. Prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy versus duodenal stenting for malignant gastric outflow obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:239–242. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chandrasegaram MD, Eslick GD, Mansfield CO, et al. Endoscopic stenting versus operative gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1870-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaw M, Singh S, Gagneja H, Azad P. Role of self-expandable metal stents in the palliation of malignant duodenal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:646–650. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8527-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mutignani M, Tringali A, Shah SG, et al. Combined endoscopic stent insertion in malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction. Endoscopy. 2007;39:440–447. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Hooft JE, Uitdehaag MJ, Bruno MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of the new WallFlex enteral stent in palliative treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (DUOFLEX study): a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1059–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim TO, Kang DH, Kim GH, et al. Self-expandable metallic stents for palliation of patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction caused by stomach cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:916–920. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]