Abstract

The EUCOMM and KOMP programs have generated targeted conditional alleles in mouse embryonic stem cells for nearly 10,000 genes. The availability of these stem cell resources will greatly accelerate the functional analysis of genes in mice and in cultured cells. We present a method for conditional ablation of genes in ES cells using vectors and targeted clones from the EUCOMM and KOMP conditional resources. Inducible homozygous cells described here provide a precisely controlled experimental system to study gene function in a model cell.

Keywords: Mouse, Genetics, Embryonic stem cells, Pluripotent, Gene targeting, Homologous recombination, Homozygous, Mutation, Conditional mutagenesis, Gene function

1. Introduction

The exploitation of mouse and human embryonic stem (ES) cells to elucidate gene function in normal biologic and disease processes is currently under-utilized and has great potential for high impact science and medicine. Unlike most other cell lines, ES cells are normal diploid cells with apparently unlimited proliferative potential [1,2]. The normal state of the mouse ES cell genome is reproducibly and reliably demonstrated by their ability to re-enter normal development and contribute to all somatic tissues and the germline, when returned to a pre-implantation embryo [3]. In addition to the use of ES cells as a model cell for basic cell biologic processes, ES cells have the capacity to differentiate into many different cell types in vitro. Tremendous progress has been made in defining culture conditions that promote the differentiation of mouse and human stem cells along specific lineages [4,5]. Furthermore, undifferentiated and differentiated ES cells can be grown in sufficient numbers for carrying out many genomic assays such as expression profiling, mass spectrometry and epigenetic profiling. Thus, ES cells provide an excellent model system for the identification of genes and genetic pathways required for basic cellular and developmental functions.

The availability of an annotated mouse genome sequence [6] has dramatically changed how gene targeting experiments are conducted and their efficiency in several respects. The availability of annotated genome sequence provides gene structures which are an essential frame work on which to design the optimum targeted allele. The genome sequence has also facilitated the ability to construct targeting vectors by homologous recombination in Escherichia coli (recombineering) in place of conventional restriction-ligation methods [7-9]. This innovation offers several advantages over the previous methods. First, constructs can be generated with nucleotide precision and therefore the design of vectors is not constrained by the convenience of relevant restriction sites. Second, these methods work with BAC clones [10] and they enable subcloning (retrieval) of the targeting vector homology arms from the BAC as well as insertion of sequences [11,12]. Finally, these methods have been developed to the point where targeting vectors can be constructed in 96 well plates in parallel with high efficiency [13].

To support and stimulate progress towards the genetic analysis of all mammalian genes, large scale gene knock-out consortia have been established with the goal of generating a complete resource of heterozygous reporter-tagged mutations in C57BL/6 mouse embryonic stem cells [14-16]. The four contributors to this resource are the European Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Programme (EUCOMM; www.eucomm.org), the NIH-sponsored Knock-out Mouse Programme (KOMP; www.knockoutmouse.org), the Canadian North American Conditional Mouse Mutagenesis Project (NorCOMM; www.norcomm.org), and the Texas Institute for Genomic Research (TIGM; www.tigm.org). By 2011, the projected combined output of these pipelines will establish heterozygous conditional mutations in 13,000 genes (8000 EUCOMM and 5000 KOMP); deletion alleles in 4000 genes (3500 KOMP and 500 NorCOMM); and random null or conditional gene trap mutations in 12,000 and 7000 genes by TIGM and EUCOMM, respectively. A common web portal providing access to these resources has been established (www.knockoutmouse.org [17]; with links to designated repositories for ordering vectors, ES cell clones and mice (see article 11).

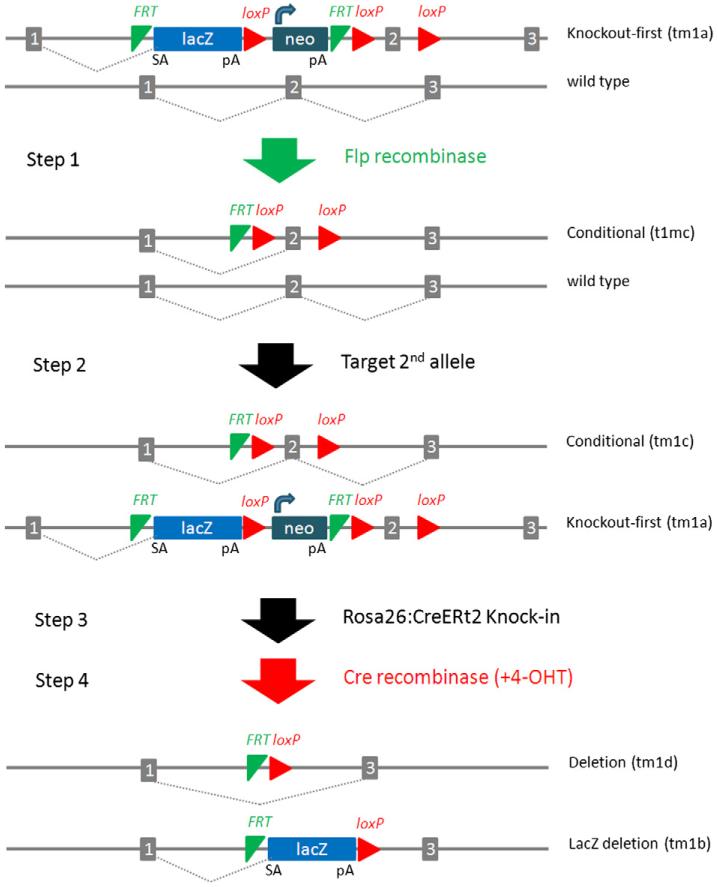

The majority of the IKMC targeted ES cell resource was generated using the knockout-first approach [18], a strategy that combines the advantages of both a reporter-tagged and a conditional mutation (Fig. 1). In contrast to standard conditional designs, the initial unmodified allele is predicted to generate a null allele through splicing to a lacZ trapping element contained in the targeting cassette. The trapping cassettes include the mouse En2 splice acceptor and the SV40 polyadenylation sequences, signals that have proven to be highly effective in creating null alleles in mice[19,20]. The knockout-first allele can be readily modified in ES cells or in crosses to transgenic Flp and Cre mice [21]. A conditional allele is generated by removal of the gene trap cassette by Flp recombinase which reverts the mutation to wild-type, leaving loxP sites on either side of a critical exon. Subsequent exposure to Cre deletes the critical exon to induce a frame-shift mutation and trigger non-sense-mediated decay of the mutant transcript.

Fig. 1.

Bi-allelic targeting strategy. Step 1: Heterozygous KO-first alleles (tm1a) are converted to conditional alleles (tm1c) by transient expression of Flp recombinase. Step 2: The second allele is targeted by re-cycling the knockout-first targeting vector, generating bi-allelic ES cells that carry a conditional allele (tm1c) and a knockout-first allele (tm1a). Step 3: Inducible Cre-recombinase is introduced into cells by high efficiency targeted insertion into the Rosa26 locus. Step 4: Gene activity is eliminated in undifferentiated or differentiated ES cell cultures through activation of Cre-recombinase with tamoxifen (4-OHT), generating deletion alleles (tm1d and tm1b).

In this article, we describe how the EUCOMM and KOMP conditional resources can be exploited to generate inducible homozygous mutations for functional analysis of genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. This strategy should be broadly applicable to functional analysis of genes in other mammalian cell systems such as rat and human pluripotent stem cells [2,22-25].

2. Serial targeting strategy

Genetic screens in cultured cells are presently hampered by the challenges of generating homozygous mutant cells. Bi-allelic mutations can be accomplished in a variety of ways. Most commonly, bi-allelic mutations are generated by serially performing two cycles of gene targeting to knockout both alleles, either by using two vectors with different selectable markers [26] or by re-cycling the vector [27]. Another approach takes advantage of spontaneous loss of heterozygosity (LOH) which can generate cells with an increased dosage of a neomycin resistance gene which, in some circumstances, can be selectively isolated [28,29]. However, these methods generate constitutive mutations and are not applicable to genes essential for cell viability, growth, and pluripotency. Therefore, inducible gene ablation strategies are needed. Furthermore, such an approach is useful to study molecular and physiologic changes in cells over time following the removal of gene activity, for example, by expression profiling.

Taking advantage of the wealth of EUCOMM/KOMP targeting vectors and targeted ES cell clones, we developed a serial targeting strategy for the generation of homozygous conditional mutations (Fig. 1). Heterozygous KO-first clones from the EUCOMM/KOMP resources are transiently exposed to Flp recombinase to generate a conditional allele. For targeted loci that express the lacZ reporter, removal of the trapping cassette by Flp can be easily monitored by the loss of β-galactosidase expression. Reverted G418-sensitive cells are then electroporated with KO-first targeting vector and desired clones that contain both the conditional and KO-first alleles are identified by PCR genotyping. Finally, ligand-inducible Cre [30] is introduced into cells using a published, high-efficiency Rosa26 targeting construct [31]. Elimination of gene function in homozygous clones is dependent on the activation of Cre recombinase in cells by treatment with the drug tamoxifen. The effect of gene ablation can thus be assayed in undifferentiated ES cells or at any time following differentiation without incurring any premature selective disadvantage prior to induction of homozygosity.

3. Methods

3.1. Ordering targeted cells from the EUCOMM/KOMP resource

The availability of knockout-first alleles for genes of interest can be found on the IKMC web portal (www.knockoutmouse.org/mart-search). If successfully targeted, vectors and ES cell clones are available upon request by following the order links on the summary page (see article 11). In addition, fully annotated nucleotide sequences of the targeting vector and the targeted allele can be downloaded in GenBank format. By way of example, we describe the generation of homozygous conditional ES cells for the Chd4 gene, a component of the nucleosome remodeling deacetylase (NuRD) complex highly expressed in embryonic stem cells. Conditional mutagenesis in mice has shown a critical role for Chd4 in T cell development [32], however, the function of Chd4 in the early embryo has not been addressed.

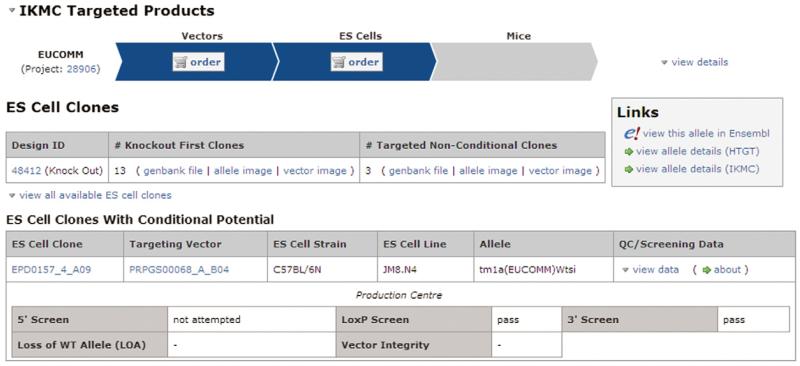

Sixteen correctly targeted clones are available from the EUCOMM repository (Fig. 2), of which thirteen are knockout-first alleles. Homologous recombination events often occur between the selection cassette (neo) and the 3′ loxP site. In the case of Chd4, 3 clones lost the the 3′ loxP site and thus their conditional potential. In extreme cases, such as the Kif6 gene, none of the correctly targeted clones retain the 3′ loxP site. Due to the high-throughput nature of the EUCOMM/KOMP pipelines, targeted clones are genotyped by long-range PCR, usually across the 3′ homology arm. The amplified products are sequenced to confirm the presence (or absence) of the 3′ loxP site. Because long-range PCR is not quantitative, some clones may be mixed. For this reason we recommend ordering at least 2 knockout-first clones from the resource. Ideally, these clones should be validated by Southern blot. However, for this application, additional rounds of targeting and sub-cloning ensure the homozygous cells are clonally pure.

Fig. 2.

Summary information for Chd4 knockout-first targeted clones. The IKMC webportal (www.knockoutmouse.org/martsearch) displays the current status of genes assigned to individual targeting pipelines with order links for vectors, targeted ES cell clones and mutant mice available from affiliated repositories. Links to detailed molecular information are provided, including annotated sequences (genbank files) and maps (allele images) of the targeted alleles. Gene-specific primers used for long-range PCR genotyping can be found by following the ‘Design ID’ link.

3.2. Feeder-free culture of C57BL/6N targeted clones

Knockout-first clones from the EUCOMM/KOMP resource are generated from electroporations of JM8 cells, an ES cell line from the C57BL/6N sub-strain of mice [33]. JM8 ES cells readily adapt to feeder-free culture and can be grown on gelatin in the presence of LIF in either standard serum-containing medium or in chemically-defined serum-free medium. The absence of feeders is ideal for visualizing cellular phenotypes and for biochemical experiments.

3.2.1. Materials

ES cell medium (M10G) is prepared by adding the following to 500 ml KNOCKOUT DMEM (Invitrogen 10829-018): 50 ml FBS (Invitrogen), 5 ml l-glutamine (100×; Invitrogen 25030-024), 5 ml 100× β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma M7522; 360 μl in 500 ml PBS, filter-sterilized), 5 ml PEN STREP (100×; Invitrogen 15140-122) and LIF (ESGRO; Millipore ESG1107, dilute as directed). Medium is stored at 4 °C and discarded after 2 weeks. Trypsin solution is prepared by adding 0.1 g EDTA (Sigma E6511) and 0.5 g d-glucose (Sigma G7528) to 500 ml PBS, filter sterilized, then adding 5 ml chicken serum (Invitrogen 16110-082) and 20 ml 2.5% trypsin (Invitrogen 151090-046). Aliquots are stored at −20 °C. Gelatin (0.1% solution) is prepared by adding 25 ml 2% gelatin (Sigma G1393) to 500 ml PBS. Freezing medium is made fresh before use by adding dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma D2650) to M10G medium to a final concentration of 10% (v/v) and filter sterilized.

3.2.2. Methods

Before starting, pre-warm M10G, trypsin and PBS in a 37 °C water bath. To gelatinize tissue culture dishes or flasks, add 0.1% gelatin solution to cover the surface and aspirate (no incubation is required). To thaw cells from a frozen vial, warm the tube in your hand and transfer the contents into 10 ml containing M10G medium. Spin the cells (1000×g) for 3 min, aspirate, and resuspend gently in M10G. Transfer the cell suspension to appropriate-sized gelatinized well or dish. As a guide, JM8 cells are growing optimally when cells will reach confluence in 2 d after passing the cells at a 1:6 dilution. Lower dilutions may be needed initially after thawing cells and during expansion. We recommend seeding the cells at different dilutions (between 1:3 and 1:6) and to carry on with the cells that attain confluence in 2 d.

Aspirate media from a near-confluent dish or flask and wash the cells two times with pre-warmed PBS.

Add pre-warmed trypsin, rock dish to cover all cells and incubate at 37 °C for 5–7 min. While cells are incubating, coat dishes with 0.1% gelatin, aspirate.

Add 5–10 volumes of M10G medium to inactivate the trypsin. Pipette up and down gently 3–4 times to disperse the cells. Transfer 1/6th of cell suspension to each dish containing M10G medium. When expanding to larger dishes, adjust dilution of cells proportional to surface area. Incubate plates in a 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator.

Change medium the following day and repeat process on day 2. If the cells have not reached confluence in 2 d, pass the cells at a lower dilution or change medium and incubate for one additional day.

To freeze cells, trypsinize confluent cultures as above, add 5–10 volumes of M10G medium to inactivate the trypsin and pellet cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g). Aspirate medium and gently resuspend the cell pellet in freezing medium (M10G + 10% DMSO). Aliquot into cryovials and put them immediately in a −80 °C freezer. For long-term storage, transfer cryovials to liquid nitrogen.

3.3. Generation of the conditional allele with Flp recombinase

3.3.1. Materials

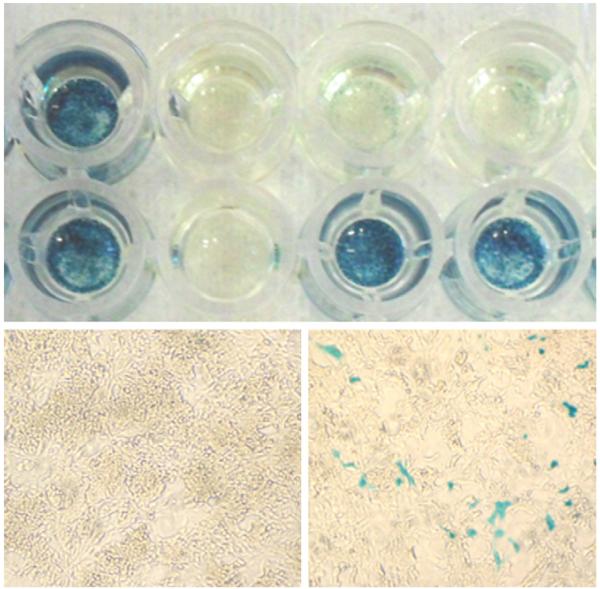

The trapping cassette is removed by transient expression of Flp recombinase in cells to generate a conditional allele (see Fig. 1). We use the CAGGs-Flpo-IRES-puro plasmid [34] which expresses codon-optimized Flp recombinase driven from a strong ES cell promoter. Forty micrograms of circular pCAGGs-Flpo plasmid is used to transfect between 1 and 3 × 107 cells (from 2 × 10 cm dishes or 1 × 75 cm2 flask of near-confluent cells). Electroporations are carried out using a BioRad Gene Pulser II (equipped with a capacitance extender). The proportion of cells that excise the trapping cassette is greatly enriched (from 10% to 90%) by transient selection with puromycin to eliminate cells that have not taken up the Flp expression plasmid. A final concentration of 1 μg/ml puromycin (Sigma P8833) is recommended for experiments in JM8 ES cells. For knockout-first cells that express the lacZ reporter, the excision of the trapping cassette by Flp recombinase is easily monitored by histochemical staining with X-gal (Fig. 3), but the excision should be confirmed by long-range PCR. If LacZ expression is not detectable, clones must be genotyped by long-range PCR (see Section 3.6). For staining cells with X-gal, prepare 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.3 by dissolving 3.74 g/l sodium phosphate, monobasic (Sigma S9638) and 10.35 g/l sodium phosphate, dibasic (Sigma S9763) in distilled water. Xgal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside, Sigma B4252) is dissolved in dimethylformamide (Sigma D4551) at a concentration of 50 mg/ml and stored in the dark at −20 °C. Prepare fix, wash and staining solutions as follows:

Fix solution: 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3), 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma G7776).

Wash solution: 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3), 2 mM MgCl2.

Staining solution: 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.3), 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide (Sigma P9387), 5 mM potassium ferricyanide (Sigma P8131), 1 mg/ml X-gal (filter before use to avoid crystal formation).

Fig. 3.

LacZ staining of Flp-treated ES cell clones. X-gal staining of expanded clones after transient transfection of Chd4 knockout-first cells with Flp recombinase. A complete loss of β-galactosidase expression is observed in most clones (top and bottom left panels). Contamination of LacZ-positive cells can be detected in some of the wells (bottom right panel).

3.3.2. Methods

One day prior to electroporation, precipitate 40 μg pCAGGs-Flpo plasmid (33) with ethanol in an eppendorf tube and spin down the DNA in a microfuge wash the DNA pellet twice in 70% ethanol and evaporate off the ethanol in a laminar flow hood for 20–30 min. Add 0.1 ml sterile PBS and leave the sample to resuspend overnight in the hood. Change the media on near-confluent ES cell cultures 3–4 h before electroporation. Pre-warm PBS and trypsin in 37 °C water bath. Room-temperature PBS is also need for washing cells prior to electroporation.

Trysinize the cells as described above (Section 3.3.2) and add 20 ml M10G medium to stop the trypsin. Pellet the cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g) and resuspend the cells in 10 ml room-temperature PBS. Count an aliquot of the cell suspension in a hemocytometer to determine the total cell number. Pellet the cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g) and resuspend the cells in a final volume of 0.7 ml room-temperature PBS.

Set the electroporator to 250 V/500 μF (on high capacitance setting using the capacitance extender unit). With a 1 ml pipette, add the cell suspension to the the eppendorf tube containing the pCAGGs-Flpo plasmid, mix and transfer the sample to an electroporation cuvette (0.4 cm gap; BioRad). Electroporate the sample (~6–7 ms time constant) and let the cells recover for 20 min in the hood. While waiting, gelatinize three 10 cm dishes.

Remove the cell suspension from the cuvette and add to 10 ml M10G medium. Plate 5 × 106, 2 × 106 and 1 × 106 cells onto gelatinized 10 cm dishes, adding M10G to a final volume of 10 ml. For even plating, mix the cells by gentle pipetting and place in 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator.

Change the medium on all plates the following day. Thirty-six hours post-electroporation, replace the medium with M10G containing 1 μg/ml puromycin and maintain drug selection for 2 d, changing the medium every day. Withdraw drug selection on d 4 and allow the surviving cells to grow for several days in M10G until colonies are visible, changing the medium every 2 d.

When colonies are ~1 mm in diameter, replace the medium in the dish with 10 ml room-temperature PBS. Using a dissecting microscope, dislodge and pick 24–48 colonies in a volume of 15 μl with a 20 μl Pipetteman. Dispense each colony into a well of a 96-well round bottom plate containing 15 μl of trypsin and incubate the plate at 37 °C for 15 min. Stop the trypsin by adding 170 μl M10G, gently pipette up and down five times to disperse the colonies, and transfer the cells to a gelatinized 96-well tissue culture plate.

Change the medium every day until most of the wells are nearly confluent (3–4 d). Split the clones at a 1:3 dilution onto three gelatinized 96-well plates for X-gal staining, preparation of genomic DNA for genotyping, and expansion of conditional clones. Change the medium every day until confluent (2–3 d).

To prepare genomic DNA for genotyping, drain media from one 96-well plate by inversion and blot on paper towels. Lyse cells in 100 μl lysis buffer (see Section 3.5.1), incubate at 65 °C for 4 h, heat inactivate at 90 °C by placing the plate on the surface of a heating block for 10 min and store the plate at −20 °C.

To stain for β-galactosidase, drain the medium from the second 96-well plate and fix cells for 5 min in 100 μl fix solution. Wash the cells twice with 200 μl wash solution (2 min), then add 50 μl staining solution to each well and incubate overnight at 37 °C.

To expand the clones, trypsinize the clones in the third 96-well plate and seed the cells onto a gelatinized 48-well plate.

Select clones that are devoid of β-galactosidase-positive cells for further expansion (or clones that carry only the conditional allele by PCR genotyping). Before proceeding to the next step, it is critical to confirm that the Flp-treated clones are pure and sensitive to both G418 and puromycin. Contamination of revertant clones with G418-resistant and/or puromycin-resistant cells will interfere with the targeting second allele and/or introduction of CreERT2, respectively. Expand the clones from 48- to 12- to 6-well plates in triplicate in M10G, M10G + 150 μg (active)/ml G418 (Geneticin, Invitrogen 11811-023), and M10G + 1 μg/ml puromycin. Only cells cultured in M10G should survive. To freeze expanded clones from 6-well plates, trypsinize each well in a volume of 0.5 ml for 5–7 min at 37 °C, stop the reaction with 4.5 ml M10G and pellet the cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g). Resuspend the cell pellet in 1 ml M10G medium containing 10% (v/v) DMSO and freeze 2 × 0.5 ml aliquots in cryovials. Each aliquot can be thawed onto 6-well gelatinized dishes and should reach confluence in 2 days.

Note: If none of the Flp-treated clones are pure, sub-cloning is required. To obtain subclones, seed 2000 cells onto a gelatinized 10 cm dish and culture in M10G until colonies are visible. Repeat the process above from step 5.

3.4. Targeting the 2nd allele in Flp-reverted clones

3.4.1. Materials

Clonally pure, Flp-treated cells isolated above are electroporated with the knock-out first targeting vector obtained from the repository to generate bi-allelic targeting events (conditional/knockout-first). Typically, 15-25 μg of linearized vector DNA is used in electroporations of 2–3 × 107 cells (2 × 10 cm dishes or 1 × 75 cm2 flask). Electroporations are carried out with a BioRad Gene Pulser using a high voltage, low capacitance setting (800 kV, 3 μF). 150 μg (active)/ml G418 (Geneticin, Invitrogen 11811-023) is recommended for gene targeting experiments in JM8 ES cells. As controls, untransfected cells are cultured in G418-containing medium and in puromycin-containing medium to check for low-level contamination of the cultures with G418-resistant and/or puromycin-resistant cells. If colonies appear on the control plates, the Flp-treated clone(s) may require a second round of sub-cloning (see Note for Section 3.3.2).

The knockout-first targeting construct from the repository can be verified by sequencing, or more simply, by comparing a restriction digest of the plasmid to the expected fragment sizes of vector sequence in silico. We use DNASTAR software to upload the vector sequence (Genbank format) and generate a virtual gel for one or more common 6-cutter restriction enzymes. Knockout-first targeting vectors clones are supplied in the DH10B strain of E. coli. It is important to check the antibiotic resistance marker in the map or annotated sequence of the vector as a number of different antibiotic-resistance genes were used in their construction. Each targeting vector contains a unique AsiSI site for linearizing the vector prior to electroporation.

3.4.2. Methods

3.4.2.1. Preparation of the targeting vector for electroporation

Vector DNA prepared from bacterial cultures on Qiagen columns is suitable for electroporation of ES cells. Allow two days for preparing the DNA for electroporation.

In an eppendorf tube, digest 5–15 μg vector DNA with AsiSI (New England Biolabs) and run 100 ng on a gel to check that the digestion is complete (if not, add additional enzyme and incubate for longer).

Adjust the concentration of NaCl to 0.1 M and add 2 volumes of ethanol. Mix well by inversion and precipitate the linearized vector DNA on ice for 5 min.

Spin in microfuge for 10 min. Wash the DNA pellet twice with 70% ethanol and remove excess ethanol after the second wash.

Allow the DNA pellet to air dry in laminar flow hood for 20–40 min. Resuspend the semi-dry pellet in 0.1 ml sterile PBS and allow the sample to dissolve overnight in the hood.

3.4.2.2. Electroporation of ES cells

Change the media on near-confluent ES cell cultures 3–4 h before electroporation. Pre-warm PBS and trypsin in 37 °C water bath. Room-temperature PBS is also need for washing cells prior to electroporation.

Trysinize dishes of confluent cells as described above (Section 3.3.2). After adding M10G to stop the trypsin, pellet cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g) and resuspend in 20 ml room-temperature PBS. Count cells in a hemocytometer. As a control, seed two gelatinized 10 cm dishes with 5 × 106 cells in 10 ml M10G medium and place in 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator. Pellet the remaining cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000 ×g) and resuspend the cells in a final volume of 0.7 ml room-temperature PBS.

Set the electroporator to 800 V/3 μF. With a 1 ml pipette, add the cell suspension to the linearized vector in the eppendorf tube, mix and transfer the sample to an electroporation cuvette (0.4 cm gap; BioRad). Electroporate the sample (~0.04 ms time constant) and allow the cells recover for 20 min in the hood. While waiting, gelatinize three 10 cm dishes.

Remove the cell suspension from the cuvette and add to 10 ml M10G medium. Plate 1 × 107, 5 × 106, 2 × 106 cells onto gelatinized 10 cm dishes, adding M10G to a final volume of 10 ml. For even plating, gently mix the cells by pipetting and place in a 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator.

Begin drug selection the following day. The experimental plates and one control plate are cultured in M10G + 150 μg (active)/ml G418. The second control plate is cultured in M10G + 1 mg/ml puromycin. The medium is changed every day for the first 4 d of selection and then every other day until colonies are visible by eye. No colonies should appear on the control plates (see Note for Section 3.3.2 above).

When colonies are ~1 mm in diameter, pick 48–96 colonies and culture in gelatinized 96-well plates as described in the previous section. Since all clones will be screened by long-range PCR, we recommend freezing a copy of cells until genotyping is completed. To freeze clones in a 96-well plate, wash cells twice with pre-warmed PBS and add 25 ml trypsin. Incubate the plate at 37 °C for 5–7 min and stop the trypsin with 125 μl filter-sterilized M10G medium containing 12% DMSO (v/v). Disperse cells by gentle pipetting and store the plate in a −80 °C freezer.

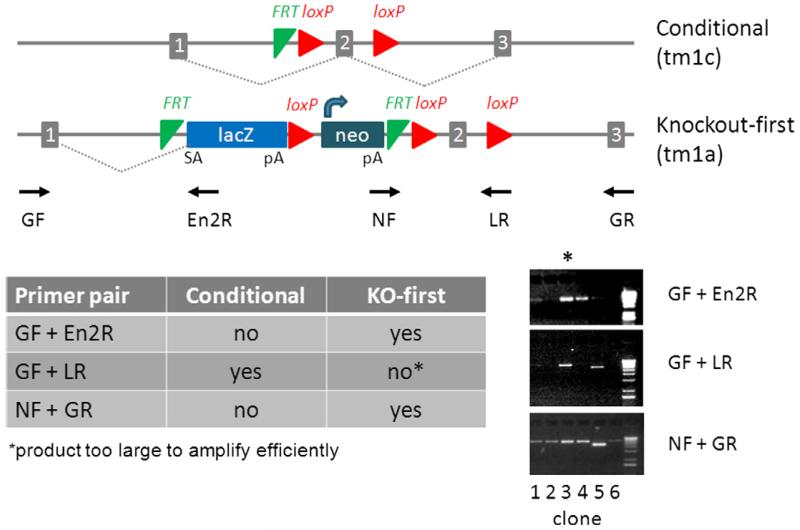

3.5. Genotyping clones by long-range PCR

Following the second round of gene targeting, long-range PCR genotyping is used to identify ES cell clones which have targeted mutations in both copies of the gene of interest – one conditional allele and one knock-out first allele. The genotyping strategy outlined in Fig. 4 is designed to achieve the following objectives: (1) independently assay for the presence of both the conditional and knock-out first alleles and (2) confirm targeting at the desired locus (as opposed to random vector integration). Finally, to conclusively demonstrate the presence of both modified alleles in individual cells it is advisable to repeat this genotyping assay again following the final step of the serial targeting process (introduction of CreERT2 at the Rosa26 locus) and confirm that subclones retain both alleles.

Fig. 4.

Identification of bi-allelic targeted clones by long-range PCR. The knockout-first allele is detected with a gene-specific primers outside of the 5′ homology (GF) and 3′ homology (GR) arms in combination with vector-specific primers to the En2 splice acceptor (En2R) and neo gene (NF), respectively. The conditional allele, but not the knockout-first allele is detected with GF and a primer to the 3× loxP site (LR). The knockout-first allele is >5 kb larger than the conditional allele, too large to be amplified with the GF/LR primer pair. In this example, clone 3 is positive for the knockout-first and conditional allele, indicating bi-allelic targeting. Clones 1 and 4 have re-targeted the conditional allele. The size of the amplified product in clone 5 is smaller than expected, suggesting a deletion has occurred in the locus.

3.5.1. Materials

Genomic DNA for genotyping is prepared by direct lysis of cells in the following buffer:

Cell lysis buffer: 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.45% NP40 (Igepal CA-630, Sigma I8896), 0.45% Tween 20 (Sigma P9416), adding proteinase K powder (Sigma P6556) to 1 μg/ml immediately prior to use.

Desalted 25-mer oligonucleotides (Sigma, 20 pmol synthesis) are used for long-range PCR. The sequence of vector-specific primers are as follows:

En2R: 5′- TGTTAGTCCCAACCCCTTCCTCC

NF: 5′- GGTACCGCGTCGAGAAGTTCCTATT

LR: 5′-TGAACTGATGGCGAGCTCAGACCAT

Gene-specific primers for long-range PCR are automatically generated from genomic sequence outside of the 5′ (GF3/4) and 3′ (GR3/4) homology arms for each targeted allele. These sequences can be found by following the ‘Design ID’ link for targeted ES cell clones (see Fig. 2). LR-PCR primers used for the genotyping the Chd4 targeted allele are:

| GF3 | CACATTCATTGCAAGGTCGGTATCTTCTC |

| GF4 | GAGAGGCAGCATGCAGTAGCCTAGTGAG |

| GR3 | CATCTGTGCCATGGTGCGCATGTGTGCAG |

| GR4 | CACTCTTCTCTTACCATTGAAGCGATC |

We have obtained satisfactory results with a number of different long range DNA amplification systems. Here we describe the use of the SequalPrep Long-Range PCR kit (Invitrogen A10498).

3.5.2. Methods

For long-range PCR analysis, 96-well plates of cell lysates (from step 7, Section 3.3.2) are thawed and placed on ice. Pipette the contents of each well up and down a few times using a multichannel pipette. Lysates are diluted 1:10–1:20 in 10 mM Tris pH8 in a 96-well reaction plate for PCR. Diluted lysates can be stored indefinitely at −20 °C. To set up the PCR reaction, combine the following:

1 μl of diluted cell lysate.

9 μl primer mix (0.4 μl 20 pmol/μl of each primer, 8.2 μl PCR-grade water).

10 μl SequalPrep master mix (2 μl 10X reaction buffer including dNTPs, 0.2 μl 100% DMSO, 1 μl 5X enhancer A, 1 μl 5X enhancer B, 0.3 μl sequalprep enzyme, 5.5 μl PCR-grade water).

Seal plate with a thermocycler seal, briefly spin the plate in a bench-top centrifuge and amplify the products using the following cycling conditions:

93 °C for 3 min.

8 cycles: 93 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 30 s (+10 s each additional cycle).

25 cycles: 93 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, 68 °C for 6 min (+10 s each additional cycle).

7 min extension period at 68 °C.

This protocol has been used successfully in both MJ Research DNA Engine Tetrad and Applied Biosystems Gene Amp PCR System 9700 thermocyclers.

3.6. Introduction of Cre-ERT2 into homozygous clones

3.6.1. Materials

Targeting of the tamoxifen-responsive CreERT2 fusion protein to the Rosa26 locus [31] is reliably a very efficient event in mouse ES cells, occurring in >90% of drug-selected clones. Consequently, this step can be done on a small scale, with fewer cells (a confluent 25 cm2 flask or 10 cm dish) and less input vector DNA (2–5 μg). The targeting vector is linearized with SfiI (New England Biolabs) for 4 h at 50 °C and prepared for electroporation as described in Section 3.4.2 above.

3.6.2. Methods

Expand two homozygous targeted clones and one heterozygous clone to serve as a control. Freeze stock and seed a 25 cm2 flask or 10 cm dish of each for electroporation. Change the media on near-confluent ES cell cultures 3–4 h before electroporation. Pre-warm PBS and trypsin in 37 °C water bath. Room-temperature PBS is also need for washing cells prior to electroporation.

Trysinize flasks of confluent cells as described above (Section 3.3.2). After adding M10G to stop the trypsin, pellet cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g) and resuspend in 20 ml room-temperature PBS. Count cells in a haemocytometer. Pellet the cells by centrifugation (3 min, 1000×g) and resuspend in a final volume of 0.7 ml room-temperature PBS.

Set the electroporator to 800 V/3 μF. With a 1 ml pipette, add the cell suspension to the linearized vector in the eppendorf tube, mix and transfer the sample to an electroporation cuvette (0.4 cm gap; BioRad). Electroporate the sample (~0.04 ms time constant) and allow the cells recover for 20 min in the hood. While waiting, gelatinize two 10 cm dishes/cell line to be electroporated.

Remove the cell suspension from the cuvette and add to 3 ml M10G medium. Plate 1 and 2 ml of cells onto gelatinized 10 cm dishes, adding M10G to a final volume of 10 ml. For even plating, gently mix the cells by pipetting and place in a 37 °C/5% CO2 incubator.

Begin drug selection the following day. Plates and are cultured in M10G + 1 μg/ml puromycin. The medium is changed every day for the first 4 days of selection and then every other day until colonies are visible by eye.

When colonies are ~1 mm in diameter, pick 12–24 colonies for each of the clones targeted and culture in gelatinzed 96-well plates as described in the previous sections.

Due to the high efficiency of targeting with the Rosa26:CreERT2 construct we do not find it necessary to confirm homologous recombination in the resulting clones but rather we screen the resulting clones for tamoxifen-responsive Cre activity.

3.7. Elimination of gene activity with tamoxifen

3.7.1. Materials

A 1.5 mM stock solution of 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (Sigma H6278) is prepared by dissolving 10 mg of 4-OHT in 17.2 ml 99% ethanol and stored at 4 °C (or −20 °C for long-term storage).

3.7.2. Methods

To induce gene inactivation by tamoxifen treatment, individual clones are seeded in duplicate gelatinized multi-well dishes at normal passage density. The following day, the media for one set of wells is replaced with M10G medium containing 0.4 μM 4-OHT and the duplicate wells are replaced with M10G containing an equivalent volume of 99% ethanol. Twenty-four hours later, the cells should be near confluent.

The Cre-mediated deletion event occurs quite rapidly in the ES cell genome. In our experience deletion of the floxed/critical region is usually complete in the population of cells treated for 24 h with drug (PT, unpublished data). At this point cells are screened for Cre-mediated activation of the mutation by short range PCR, inferring correct targeting of CreERT2 to the Rosa26 locus in clones that carry the deleted allele. PCR primers are designed to detect a complete deletion of the floxed critical exon. Once OHT-responsive clones are identified, multiple independent clones may be expanded and frozen for further analysis.

For molecular or cellular phenotyping of mutant cells it is important to establish the time frame over which wild-type RNA or full-length protein is eliminated prior to the onset of any change in morphology or growth rate of the cells. In this example, we analyzed tamoxifen-treated and untreated clones by Western blot (Fig. 5). Complete loss of Chd4 protein occurs within 5 days, during which time the cells display no overt phenotype. Shortly thereafter, strong effects on cell morphology and proliferation are observed in homozygous cells compared to non-treated control cells. We are currently examining gene expression changes resulting from inactivation of this critical component of a chromatin remodeling activity important in ES cells [35].

Fig. 5.

Tamoxifen-induced ablation of Chd4 protein expression. Western blot of two Chd4 bi-allelic targeted clones (tm1c/tm1a) and a heterozygous targeted clone (tm1a/+) after two passages following treatment with ethanol (−4OHT) and tamoxifen (+4OHT). Activation of Cre recombinase in homozygous targeted clones removes the critical exon from the conditional targeted allele (tm1c) to generate the deletion allele (tm1d), eliminating expression of wild-type Chd4 protein (w.t.). The Chd4 antibody (Bethyl Laboratories A301-081A) also detects truncated Chd4 protein expressed from the tm1a and tm1b alleles.

Acknowledgments

We thank Derek Matthews for assisting us in preparing this manuscript for publication. This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- [1].Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bradley A, Evans M, Kaufman MH, Robertson E. Nature. 1984;309:255–256. doi: 10.1038/309255a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Guan K, Rohwedel J, Wobus AM. Cytotechnology. 1999;30:211–226. doi: 10.1023/A:1008041420166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Murry CE, Keller G. Cell. 2008;132:661–680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Waterston RH, Lindblad-Toh K, Birney E, Rogers J, Abril JF, Agarwal P, Agarwala R, Ainscough R, Alexandersson M, et al. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zhang Y, Buchholz F, Muyrers JP, Stewart AF. Nat. Genet. 1998;20:123–128. doi: 10.1038/2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Muyrers JP, Zhang Y, Testa G, Stewart AF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1555–1557. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Angrand PO, Daigle N, van der Hoeven F, Scholer HR, Stewart AF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:e16. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Osoegawa K, Tateno M, Woon PY, Frengen E, Mammoser AG, Catanese JJ, Hayashizaki Y, de Jong PJ. Genome Res. 2000;10:116–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Liu P, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. Genome Res. 2003;13:476–484. doi: 10.1101/gr.749203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Chan W, Costantino N, Li R, Lee SC, Su Q, Melvin D, Court DL, Liu P. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:e64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Posner I, Sarov M, Hutchins JR, Hériché JK, Toyoda Y, Pozniakovsky A, Weigl D, Nitzsche A, Hegemann B, Bird AW, Pelletier L, Kittler R, Hua S, Naumann R, Augsburg M, Sykora MM, Hofemeister H, Zhang Y, Nasmyth K, White KP, Dietzel S, Mechtler K, Durbin R, Stewart AF, Peters JM, Buchholz F, Hyman AA. Nat. Methods. 2008;5:409–415. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Austin CP, Battey JF, Bradley A, Bucan M, Capecchi M, Collins FS, Dove WF, Duyk G, Dymecki S, Eppig JT, et al. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:921–924. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Auwerx J, Avner P, Baldock R, Ballabio A, Balling R, Barbacid M, Berns A, Bradley A, Brown S, Carmeliet P, et al. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:925–927. doi: 10.1038/ng0904-925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].International Mouse Knockout Consortium Cell. 2007;128:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ringwald M, Iyer V, Mason JC, Stone KR, Tadepally HD, Kadin JA, Bult CJ, Eppig JT, Oakley DJ, Briois S, Stupka E, Maselli V, Smedley D, Liu S, Hansen J, Baldock R, Hicks GG, Skarnes WC. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;6 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Testa G, Schaft J, van der Hoeven F, Glaser S, Anastassiadis K, Zhang Y, Hermann T, Stremmel W, Stewart AF. Genesis. 2004;38:151–158. doi: 10.1002/gene.20012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Skarnes WC, Auerbach BA, Joyner AL. Genes Dev. 1992;6:903–918. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.6.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mitchell KJ, Pinson KI, Kelly OG, Brennan J, Zupicich J, Scherz P, Leighton PA, Goodrich LV, Lu X, Avery BJ, Tate P, Dill K, Pangilinan E, Wakenight P, Tessier-Lavigne M, Skarnes WC. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:241–249. doi: 10.1038/90074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Branda CS, Dymecki SM. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:7–28. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00399-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Buehr M, Meek S, Blair K, Yang J, Ure J, Silva J, McLay R, Hall J, Ying QL, Smith A. Cell. 2008;135:1287–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li P, Tong C, Mehrian-Shai R, Jia L, Wu N, Yan Y, Maxson RE, Schulze EN, Song H, Hsieh CL, Pera MF, Ying QL. Cell. 2008;135:1299–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bu L, Gao X, Jiang X, Chien KR, Wang Z. Cell Res. 2010;20:379–382. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].teRiele H, Maandag ER, Clarkem A, Hooper M, Berns A. Nature. 1990;348:649–651. doi: 10.1038/348649a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Abuin A, Bradley A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:1851–1856. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mortensen RM, Conner DA, Chao S, Geisterfer-Lowrance AA, Seidman JG. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:2391–2395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lefebvre L, Dionne N, Karaskova J, Squire JA, Nagy A. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:257–258. doi: 10.1038/85808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Feil R, Brocard J, Mascrez B, LeMeur M, Metzger D, Chambon P. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:10887–10890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Vooijs M, Jonkers J, Berns A. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:292–297. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Williams CJ, Naito T, Arco PG, Seavitt JR, Cashman SM, De Souza B, Qi X, Keables P, Von Andrian UH, Georgopoulos K. Immunity. 2004;6:719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Pettitt SJ, Liang Q, Rairdan XY, Moran JL, Prosser HM, Beier DR, Lloyd KC, Bradley A, Skarnes WC. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:493–495. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kranz A, Fu J, Duerschke K, Weidlich S, Naumann R, Stewart AF, Anastassiadis K. Genesis. 2010;48:512–520. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kaji K, Caballero IM, MacLeod R, Nichols J, Wilson VA, Hendrich B. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:285–292. doi: 10.1038/ncb1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]