Positron Emission Tomography (PET) has become a standard clinical practice in the diagnostic or prognostic imaging of cancer mainly due to the great success of [18F]FDG (2-deoxy-2-18F-fluoro-D-glucose) for non-invasive detection of glucose uptake in tumors.[1] Currently 11C and 18F are the most commonly used PET nuclides for the development of PET imaging probes. However, the short half-lives of these two radioisotopes (11C: t1/2 = 20.3 m; 18F: t1/2 = 109 m) limit their applications to biomolecules with relatively fast in vivo biodistribution kinetics and the chemical procedures to incorporated these isotopes must be carried out in the proximity of a biomedical cyclotron. Among the non-standard PET nuclides, 64Cu (t1/2 = 12.7 h; β+: 0.653 MeV, 17.4%) has drawn considerable interest in PET research due to its low positron range, commercial availability, and reasonably long decay half life. Such characteristics could enable a variety of imaging applications involving peptides, antibodies/fragments, and nanoparticles.[2, 3]

It has been demonstrated that multimerization of a targeting molecule on one scaffold can efficiently improve cell-specific binding affinity by several orders of magnitude.[3] As such, various approaches have been reported to exploit multivalent scaffolds for the construction of molecular imaging probes.[4–10] However, the chemistries are often complicated and become even more so when a bifunctional chelator (BFC) must be conjugated to introduce a metal radionuclide to such a separately multimerized construct for nuclear imaging. Herein we present an approach to take advantage of the pendent arms of the commonly used BFCs of radiometals to build simplified but potentially versatile multivalent scaffolds for multimeric presentation of targeting molecules. This type of multivalent scaffolds features a chelator that forms a stable and neutral complex with a radiometal and multiple functional groups for the anchoring of targeting molecules. If required by in vivo pharmacokinetics, PEG chains can be introduced between the chelate and targeting moieties.

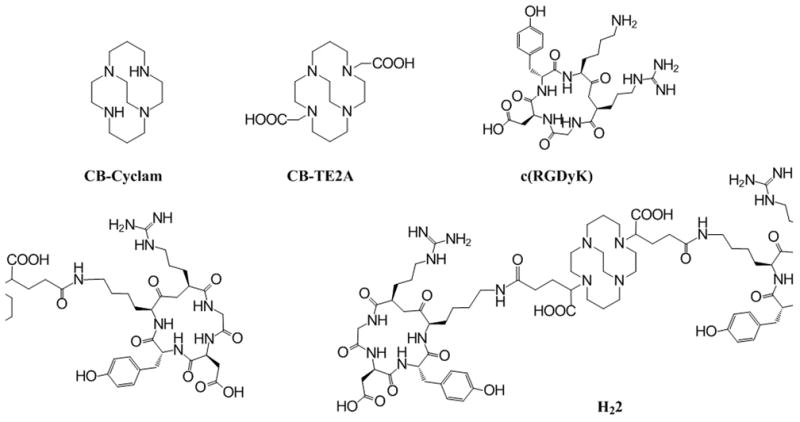

To test the rationale of our design, we use a cyclic RGD peptide (c(RGDyK),[5, 11] a well-validated αυβ3 integrin ligand, for the construction of a divalent PET imaging probe constructed from a chelate known to have a high affinity for 64Cu (CB-TE2A. Figure 1). The divalent probe is anticipated to have a prolonged biological half-life and enhanced specific binding and retention in tissues expressing the αυβ3 integrin.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of relevant compounds

The metal complex stability is of critical importance in the design of a metal radiopharmaceutical. CB-TE2A forms one of the most stable complexes with 64Cu [12] and the Cu(II)-CB-TE2A complex is more resistant to the reductive metal loss as compared to other tetramacrocyclic complexes.[13] However its stability with 64Cu may be reduced when used as a BFC, in which one of the carboxylate groups is converted to an amide for conjugation to a targeting molecule,[14] and the 64Cu-moiety becomes positively charged. To avoid this, we choose α-bromoglutaric acid-1-tertbutyl ester-5-benzyl ester (3) for the alkylation of CB-cyclam, which allows selective deprotection of the carboxylate groups by two separate procedures to conjugate with c(RGDyK) via the peripheral carboxylates to afford H21 and H22, respectively. As such, the unique feature of CB-TE2A is preserved in the conjugates where the two inner carboxylates can form a neutral octahedral complex with 64Cu(II) along with the four nitrogen atoms of the macrocycle.

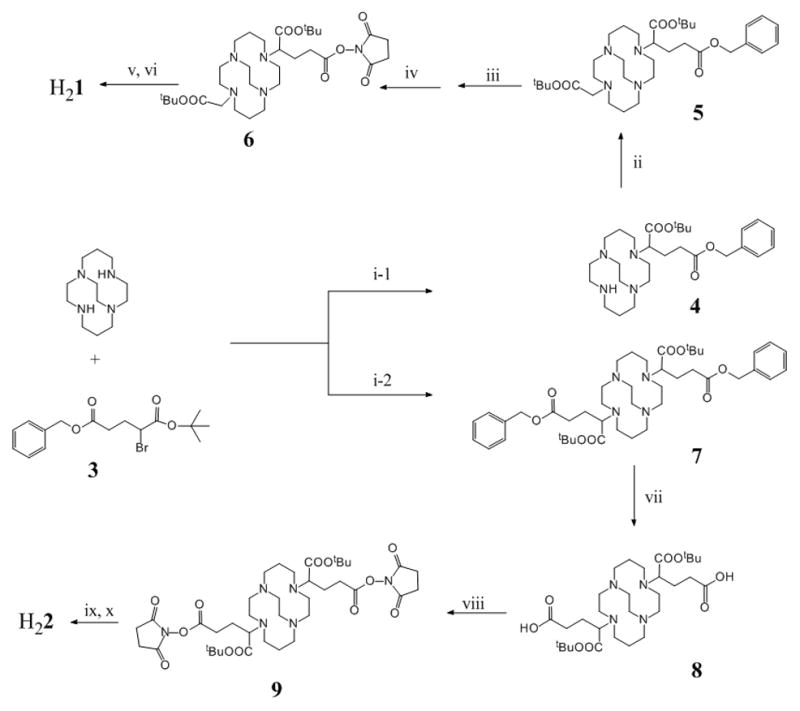

To evaluate the anticipated multivalent effect, a recently reported CB-TE2A analog[15] was also synthesized and coupled with c(RGDyK) to form a monovalent CB-TE2A-RGD conjugate (H21) as a control for comparison. Scheme 1 shows the synthetic routes to H21 and H22. The multiple-step synthetic route involves three parts: (a) synthesis of orthogonally protected compounds 5 and 7; (b) formation of NHS-activated ester intermediates 6 and 9 after selective deprotection of the peripheral carboxylate groups; and (c) conjugation of c(RGDyK) to the NHS esters followed by acid deprotection of the inner carboxylate groups to form the products: H21 and H22. Alkylation of CB-cyclam by α-bromoglutaric acid-1-tertbutyl ester-5-benzyl ester 3 was asynchronous at the two non-bridged nitrogen atoms with the monoalkylation product 4 predominating at room temperature (35 – 55 % yield even at the presence of excess of 3).[15] In comparison, the dialkylated product, 7, was only formed at elevated temperatures. At 50 °C using two equivalents of 3 to CB-cyclam, only 20–45% of 7 was found and it was always accompanied by the monoalkylation product. Although 7 was difficult to elute from silica gel using common organic solvents, a good separation was obtained by adding 5–10% of isopropyl amine in ethyl acetate. It is noteworthy that the debenzylation of the peripheral carboxylate groups catalyzed by 10% Pd/C in a hydrogen atmosphere always resulted in formation of the corresponding esters if the reaction was carried out in an alcohol solvent. This is likely due to the “proton sponge” nature of the CB-cyclam core that induces the trans-esterification during the process of debenzylation. No clean debenzylization could be accomplished in either methanol or ethanol even in the presence of formic acid as described in literature.[15] However, a mixture of THF/H2O successful circumvented this problem and afforded debenzylation products in quantitative yield. These were then activated by NHS (N-hydroxysuccinimide) and conjugated to c(RGDyK) at the presence of 10 equivalent of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA). After HPLC purification, H21 and H22 were obtained by removal of the t-butyl groups using 95% of TFA (see the supporting information for detail).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of H21 and H22. Reagents: (i-1 and i-2) CH2Cl2, K2CO3; (ii) BrCH2COOtBu, CH2Cl2, K2CO3; (iii) and (vii) 10% Pd/C, THF/H2O; (iv) and (viii) MeCN, NHS, EDC; (vi) and (ix) c(RGDyK), DIPEA, DMF; (v) and (x) 95% TFA.

Both H21 and H22 were efficiently labeled by 64Cu at 70 °C in 0.4 M NH4OAc buffer within 30 min. The specific activity of 64Cu-1 and 64Cu-2 was in the range of 8.4 – 20.4 GBq/μmol. The in vitro stability of the 64Cu labeled peptide conjugates was evaluated in rat serum by radio-HPLC. Chromatographic results showed no release of 64Cu from the conjugates over a period of 48 h. This high stability is rendered by the CB-TE2A moiety in the conjugates. The α υβ3 binding affinities of H21 and H22 were measured by a competitive cell-binding assay using U87MG cells where 125I-echistation was employed as αυβ3-specific radioligand for the competitive displacement.[5] The U87MG cell line was chosen because the αυβ3 integrin density on the cell surface was the highest among the solid tumor cell lines that have been assessed.[16] The IC50 values of c(RGDyK), H21, and H22, which represent their concentrations required to displace 50% of the 125I-echistation bound on the U87MG cells, were determined to be 110, 139 and 35 nM, respectively (n = 5). The slightly decreased αυβ3 binding of H21 as compared to c(RGDyK) indicates a minute impact of CB-TE2A on the binding of c(RGDyK) to the αυβ3 integrin. As anticipated, H22 exhibited a strong divalent effect measured by the multivalent enhancement ratio (MVE) calculated by dividing the IC50 value of H21 by that of H22 (MVE = 4).[6] The distance between the two RGD motifs in H22 is maintained greater than 25 bonds (including the lysine spacers), the minimum spacing length required to realize multivalent binding of RGD motifs to the αυβ3 integrin.[5] It is noteworthy that as a downstream effect of multivalent binding, oligomerization of cell surface receptors could initiate cellular internalization events, which might further enhance the specific accumulation in the target tissues.[17]

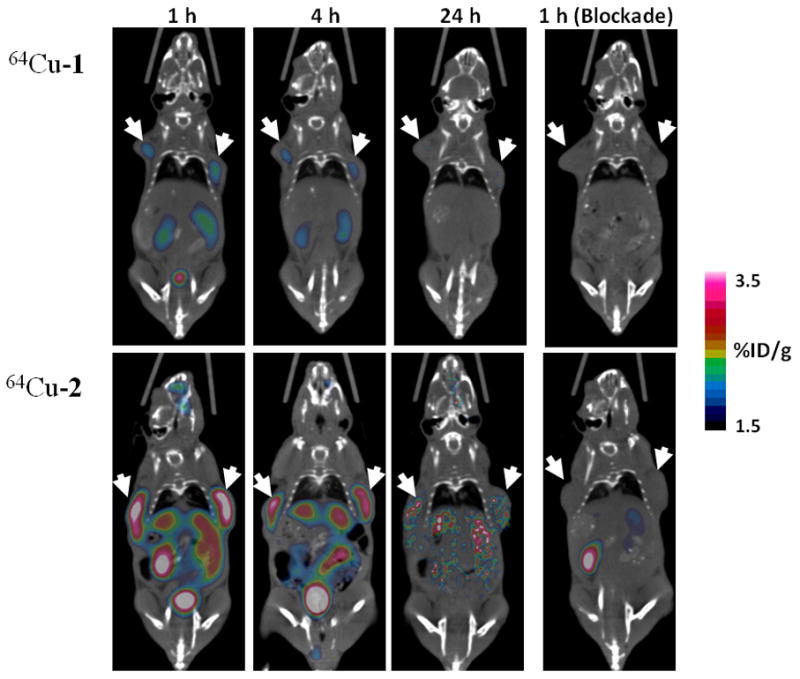

In vivo small animal imaging studies were performed on a Siemens Inveon PET-CT multimodality system. Six SCID mice (6 –7 weeks old) bearing PC-3 human prostate cancer xenografts in both front flanks (tumor size: ~ 230 mg) were randomized into two groups (n = 3) for the evaluation of 64Cu-1 or 64Cu-2, which was injected via the tail-vein. As shown in Figure 2, both tumors were visualized by 64Cu-1 and 64Cu-2 at 1 h and 4 h p.i., while 64Cu-2 consistently showed significantly stronger PET signal at all time points compared to 64Cu-1. At 24 h p.i., the tumors were still clearly visible with 64Cu-2 but rather faint with 64Cu-1. Due to the fact that the αυβ3 integrin is also expressed in other tissues (e.g. liver, kidneys, stomach, intestines) in young mice but to a lesser extent (personal communications [18]). an elevated uptake was observed in those organs with 64Cu-2 as compared to 64Cu-1. The enhanced tumor uptake and retention of 64Cu-2 may be partially attributed to the difference of in vivo kinetics of 64Cu-1 and 64Cu-2, given the higher molecular weight of 64Cu-2. Indeed, 64Cu-2 was not cleared as efficiently as 64Cu-1 from kidneys (64Cu-1: 94.7 ± 3.6 %ID excreted at 24 h p.i.; 64Cu-2: 88.2 ± 4.9 %ID excreted at 24 h p.i.; p < 0.05). The αυβ3 binding specificity of 64Cu-1 and 64Cu-2 was demonstrated by signal loss (Figure 2: 1 h blockade) in tumors after co-injection of c(RGDyK) at a dose of 10 mg/kg. The quantitative PET image data and post-PET biodistribution data are presented in Table 1 and Tables S1 – S3 (see the Supporting Information for detail).

Figure 2.

Representative microPET-CT images of PC-3 tumor bearing mice (n = 3) at 1, 4, 24 h after intravenous injection of 64Cu-1 (upper panel) and 64Cu-2 (lower panel). Images obtained with coinjection of 10 mg/kg of c(RGDyK) were only shown for 1 h blockade (right). Solid arrows indicate tumors.

Table 1.

Tumor uptake values of 64Cu-1 and 64Cu-2 as determined by PET imaging quantitation and post-PET biodistribution. Data were presented as %ID/g standard deviation (n = 3).

| 1 h PET | 4 h PET | 24 h

|

1 h PET (blockade) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | Post-PET | ||||

| 64Cu-1 | 1.95 ± 0.10 | 1.85 ± 0.26 | 1.10 ± 0.15 | 1.39 ± 0.17 | 0.31 ± 0.05 |

| 64Cu-2 | 2.92 ± 0.26* | 2.40 ± 0.22* | 1.72 ± 0.18* | 1.79 ± 0.13* | 0.71 ± 0.04* |

p < 0.05.

These data suggest that the significantly greater uptake and prolonged signal intensity of 64Cu-2 in tumor reflects the advantages of the scaffolding design of H22, which affords optimal in vivo kinetics in addition to the anticipated multivalent effects. It should be pointed out that there are two chiral centers in the pendent arms of Cu-2, which should statistically give rise to three diastereomers (R/R, S/S, and a meso R/S) even though they could not be distinguished using the techniques used in this work. While the purpose of this work is to demonstrate the feasibility of building multivalent imaging probes from a bifunctional chelator, an enantiopure isomer of 3 should be considered for future clinical applications of this type of multivalent scaffolds. Used as a sample targeting molecule in this work, c(RGDyK) can be obviously replaced by other targeting peptides or small organic molecules for imaging of various diseases or non-invasive cell surface receptor mapping. In summary, we have demonstrated a divalent scaffolding design for targeted imaging probe development. Obviously this concept can be applied to the design of other multivalent scaffolds based on NOTA (1,4,7-triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid) or DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was partially supported by a USAMRMC grant (W81XWH-08-1-0305) and two NIH grants (P01 DK058398; U24 CA126608). The authors acknowledge the generous support of a private donor that allowed the purchase of the Inveon PET-CT system. The c(RGDyK) peptide was provided by Dr. Xiaoyuan Chen at Stanford University

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org

Contributor Information

Wei Liu, Department of Radiology and Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-8542, USA, Fax: (+)1-214-645-2885.

Guiyang Hao, Department of Radiology and Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-8542, USA, Fax: (+)1-214-645-2885.

Michael A Long, Department of Radiology and Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-8542, USA, Fax: (+)1-214-645-2885.

Tiffani Anthony, Department of Radiology and Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-8542, USA, Fax: (+)1-214-645-2885.

Jer-Tsong Hsieh, Department of Urology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-9110, USA.

Xiankai Sun, Email: Xiankai.Sun@UTSouthwestern.edu, Department of Radiology and Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas 75390-8542, USA, Fax: (+)1-214-645-2885.

References

- 1.Allen-Auerbach M, Weber WA. Oncologist. 2009;14:369. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossin R, Muro S, Welch MJ, Muzykantov VR, Schuster DP. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:103. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haubner R, Wester HJ. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:1439. doi: 10.2174/1381612043384745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almutairi A, Rossin R, Shokeen M, Hagooly A, Ananth A, Capoccia B, Guillaudeu S, Abendschein D, Anderson CJ, Welch MJ, Frechet JM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811757106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li ZB, Cai W, Cao Q, Chen K, Wu Z, He L, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:1162. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.039859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montet X, Funovics M, Montet-Abou K, Weissleder R, Josephson L. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6087. doi: 10.1021/jm060515m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijkgraaf I, Kruijtzer JA, Liu S, Soede AC, Oyen WJ, Corstens FH, Liskamp RM, Boerman OC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:267. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0180-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dijkgraaf I, Rijnders AY, Soede A, Dechesne AC, van Esse GW, Brouwer AJ, Corstens FH, Boerman OC, Rijkers DT, Liskamp RM. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:935. doi: 10.1039/b615940k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen M, Oyen WJ, Massuger LF, Frielink C, Dijkgraaf I, Edwards DS, Radjopadhye M, Corstens FH, Boerman OC. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2002;17:641. doi: 10.1089/108497802320970244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu S. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:472. doi: 10.1021/mp060049x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cai W, Gambhir SS, Chen X. Methods Enzymol. 2008;445:141. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun X, Wuest M, Weisman GR, Wong EH, Reed DP, Boswell CA, Motekaitis R, Martell AE, Welch MJ, Anderson CJ. J Med Chem. 2002;45:469. doi: 10.1021/jm0103817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woodin KS, Heroux KJ, Boswell CA, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Niu W, Tomellini SA, Anderson CJ, Zakharov LN, Rheingold AL. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2005;2005:4829. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woods M, Caravan P, Geraldes CF, Greenfield MT, Kiefer GE, Lin M, McMillan K, Prata MI, Santos AC, Sun X, Wang J, Zhang S, Zhao P, Sherry AD. Invest Radiol. 2008;43:861. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318186531d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boswell CA, Regino CA, Baidoo KE, Wong KJ, Bumb A, Xu H, Milenic DE, Kelley JA, Lai CC, Brechbiel MW. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1476. doi: 10.1021/bc800039e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang X, Xiong Z, Wu Y, Cai W, Tseng JR, Gambhir SS, Chen X. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gestwicki JE, Cairo CW, Strong LE, Oetjen KA, Kiessling LL. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:14922. doi: 10.1021/ja027184x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Unpublished data in Dr. Shuang Liu’s Laboratory at Purdue University, Indiana, USA.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.