Abstract

Background and Purpose

Whole-brain irradiation (WBI) therapy produces learning and memory deficits in patients with brain tumours. Although the pathological cascade of cognitive deficits remains unknown, it may involve reduced neurogenesis within the hippocampus. Baicalein is a flavonoid derived from the roots of Huangqin, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, and has been shown to have antioxidant effects. Here, we have investigated the protective effects of baicalein on irradiation-induced impairments in hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function.

Experimental Approach

Radioprotective effects of baicalein were evaluated in C17.2 neural progenitor cells and 6-week-old male C57BL/6 mice during hippocampal neurogenesis. Mice were given a single dose of 5 Gy WBI. Changes in hippocampal neurogenesis, oxidative stress and BDNF-pCREB signalling were evaluated. Morris water maze and passive avoidance test were used to assess learning and memory.

Key Results

Baicalein protected neural progenitor cells against irradiation-induced necrotic cell death. Pretreatment with baicalein attenuated the irradiation-induced impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis by modulating oxidative stress and elevating BDNF-pCREB signalling. Furthermore, baicalein prevented the spatial learning and memory retention deficits follwing WBI.

Conclusions and Implications

Our findings suggest that baicalein can be viewed as a potential therapeutic agent that protects against the impaired neurogenesis induced by WBI, and its neurocognitive consequences.

Keywords: brain tumour, radiotherapy, cell death, neural progenitor cell, neurogenesis, oxidative stress, whole-brain irradiation

Introduction

Whole-brain irradiation (WBI) is essential for the treatment of brain tumours. However, ionizing radiation produces long-term learning and memory deficits, particularly in young children (Monje and Palmer, 2003; Laack and Brown, 2004; Achanta et al., 2009). Although the pathological cascade remains unknown, irradiation-induced cognitive deficits might underlie reduced neurogenesis within the hippocampus, which is important for learning and memory (Crossen et al., 1994; Abayomi, 1996). Hippocampal neurogenesis occurs in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus throughout life (Gheusi and Rochefort, 2002). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis can be altered by various environmental stimuli, but the process is considerably more active in young individuals (Pham et al., 2002; Park and Lee, 2011). Therefore, young patients might be more vulnerable to radiation therapy and intervention to reduce irradiation-induced hippocampal damage might be of clinical value.

Ionizing radiation dose-dependently induces the loss of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the hippocampus and subventricular zone, and is known to induce oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), including the hydroxyl radical, single oxygen and hydrogen peroxide in cells (Yoshida et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). These reactive entities can then cause functional damage or kill living cells. Many studies have shown that irradiation-induced cell death involves both apoptosis and necrosis (Rupnow and Knox, 1999; Delanian and Lefaix, 2007), and antioxidants are believed to protect neuronal cells exposed to ionizing radiation (Motomura et al., 2010; Pearlstein et al., 2010). The flavonoids are known to have antioxidative properties and thus might protect NPCs from irradiation-induced cell death (Liu and Yu, 2008; Zhang et al., 2011). Baicalein is a flavonoid derived from the roots of Huangqin, Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, a plant used in oriental medicine that has been shown to have antiallergenic, antibacterial and antioxidant effects (Gabor, 1986; Srinivas, 2010; Chan et al., 2011). Furthermore, baicalein has been shown to attenuate cellular oxidative stress by decreasing ROS generation (Kang et al., 2011).

Therefore, the present study was undertaken to investigate the protective effects of baicalein on irradiation-induced oxidative stress, cognitive deficit and cell death caused by impaired neurogenesis.

Methods

Cell cultures and treatment

C17.2 NPCs were isolated from a neonatal mouse cerebellum and immortalized (Snyder et al., 1992). This C17.2 NPCs line is known to differentiate into three brain cell types, namely, neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. C17.2 NPCs were generously provided by Dr Cepko at Harvard University, Boston, MA. C17.2 NPCs were maintained in plastic culture plates in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 5% horse serum and 2 mM glutamine in a humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere at 37°C. The cells were incubated in DMEM containing 1% FBS medium with/without baicalein, then irradiated using a 137Cs irradiator (MDS Nordion 137Cs standard source; Hanil Co., Anyang, South Korea) at a rate of ∼5.1 Gy·min−1 at room temperature; control cells were not irradiated. After irradiation, culture dishes were returned to the incubator and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2/95% air mixture.

Cell viabilities

For cell viability assays, cells were seeded in a 60 mm cultured dish and allowed to attach for 24 h. They were then treated with baicalein (1 or 10 μM) for 12 h and exposed to 16 Gy of radiation. Baicalein was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in DMEM (final 0.01% DMSO). After incubation for 24 h, media containing baicalein was removed and a solution of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) in PBS (0.5 mg·mL−1) was added to each well. After incubating for 4 h, the MTT solution was removed, and cells were dissolved in solubilization solution (DMSO : ethanol, 1:1). Formazan absorbance was measured using an elisa microplate reader at 560 nm.

Nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI)

Double staining with Hoechst 33342 and PI conveniently allows the detection of apoptotic and necrotic cells in same cell preparations (Kabakov et al., 2011). The plasma membrane is permeable to Hoechst 33342 regardless of membrane damage, and the dye emits a blue fluorescence after binding to the nucleus. However, PI is a polar nuclear stain and can only penetrate cells with damaged membranes. C17.2 NPCs were seeded in 60 mm culture dishes, allowed to attach for 24 h. Cells were pretreated with or without baicalein for 12 h and then irradiated at 16 Gy. After incubation for 24 h, Hoechst 33342 and PI were added to plates and incubated for 10 min. Stained cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

ROS measurements

Cells (2 × 105 cells·mL−1) were seeded onto 60 mm culture dishes for 24 h, treated with baicalein for 12 h and irradiated at 16 Gy. Cells were then treated with 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA; 80 μM) at 37°C for 30 min. Changes in fluorescence intensity were visualized under a fluorescence microscope using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope (Nikon). For hippocampal ROS measurement, 10 μL hippocampal homogenates were plated in 96-well plates, and 190 μL potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) was added to each well. After adding prepared 125 μM DCFDA, ROS generations were measured every 5 min for 30 min on a fluorescence plate reader with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 485 and 530 nm respectively. Florescence intensity is calculated a change per min.

Animals and treatments

All animal care and experimental procedures complied with the Guidelines from the Korea Food & Drug Administration (KFDA) and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of Pusan National University (#PNU-2011-000326). All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (McGrath et al., 2010). A total of 60 animals were used in the experiments described here. Young (5-week-old) male C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Daehan Biolink Co. Ltd. (Chungbuk, South Korea) and housed under temperature- and light- controlled conditions (20–23°C, 12 h light/12 h dark cycle). Mice were randomly allocated to a control group, a baicalein group, an irradiation group or an irradiation plus baicalein group and acclimatized for 1 week prior to baicalein administration. Baicalein was dissolved in PBS containing 2% Tween 20 and 5% ethanol and administered (10 mg·kg·day−1 i.p.) for 7 days starting on postnatal day 42. To evaluate the proliferation of newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus, mice were injected with 5′-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 100 mg·kg−1 weight, three times a day, i.p.) for two consecutive days before the administration of baicalein and irradiation. At the age of 7 weeks from postnatal day, all mice were anaesthetized with tribromethanol (240 mg kg-1; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and cranially irradiated at 5 Gy. In a preliminary experiment, a single dose of 5 Gy (137Cs at a dose rate of ∼1.59 Gy·min−1) was found to be sufficient to induce significant impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis (Supplemental Figure S2).

Tissue processing

For histological staining, animals were anaesthetized with ether and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4). Brains were then removed, placed in the same fixative solution at 4°C overnight and transferred to 30% sucrose solution for 48 h. The brains were then serially sectioned at 40 μm in the coronal plane using a freezing microtome (Microm, Walldorf, Germany). The sections were collected in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) solution containing 0.1% sodium azide and stored at 4°C. Each section containing the hippocampal formation was saved.

Quantification of newly generated cells

For immunostaining, free-floating brain sections were treated with 0.6% H2O2 in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) to block endogenous peroxidase, incubated in sodium citrate buffer containing 50% formamide for 2 h, and in 2 M HCl at 37°C for 30 min to denature DNA. Sections were then neutralized with 0.1 M borate buffer, incubated in TBS, 0.1% Triton X-100, 3% goat serum (TBS-TS) at 37°C for 30 min and then with primary anti-BrdU antibody (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, NY, USA) in TBS-TS at 4°C overnight. Sections were further incubated with a biotinylated secondary goat anti-rat lgG antibody (1:200; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) at room temperature for 3 h and then with ABC solution (avidin–peroxidase complex, Vectastain ABC reagent Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 1 h. Diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution was then added for 3 min, and stained sections were mounted onto VWR Micro Slides (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA) and coverslipped with permanent mounting medium (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) and coverslipped. Images were acquired using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope (Nikon). BrdU-labelled cells in every sixth section throughout the entire rostro-caudal region of the hippocampus were counted. The reference region consisted of the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus. All cell counts were performed by the same investigator, without knowledge of the treatments.

Double- and triple-label immunostaining

Brain sections were blocked with TBS-TS at 37°C and co-labelled with primary antibodies against BrdU and several cell markers, namely, mature neuronal marker (NeuN; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA), immature neuron marker (DCX; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), astrocyte marker (GFAP; Sigma-Aldrich) or microglia marker (Iba-1; rabbit polyclonal, Wako, Japan). Sections were then washed with TBS and incubated with secondary antibody labelled with Alexa Fluor 488, 568 or 633 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Stained sections were mounted onto slides with aqueous and dry mounting medium (Biomeda Corp., Foster City, CA, USA). Immunofluorescent images were taken using a FV10i FLUOVIEW laser confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). To avoid cross-talk between green and red channels, channels were scanned separately in multitrack mode. NeuN/BrdU, DCX/BrdU and GFAP/Iba-1 double-positive cells were counted in the SGZ in five randomly chosen fields.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) assay

BDNF protein levels were quantified using a commercially available kit (Chemicon International) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 μL of hippocampal homogenate was added to wells pre-coated with rabbit anti-human BDNF polyclonal antibody. Plates were incubated at 4°C overnight and were then washed with washing buffer. Diluted biotinylated mouse anti-BDNF monoclonal antibody (100 μL) was added to each well; plates were incubated at room temperature for 2 h and then washed with washing buffer. Plates were incubated in streptavidin-HRP conjugate solution (100 μL) for 1 h. Finally, the substrate (3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine with enhancer; 100 μL) was added, and plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μL of stop solution, which caused the blue reaction solution to turn yellow. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a plate reader.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections were treated with 0.6% H2O2 in TBS to block endogenous peroxidase, blocked in TBS-TS for 30 min and incubated with primary anti-phospho-CREB antibody (rabbit monoclonal; 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) in TBS-TS at 4°C overnight. They were then incubated with biotinylated secondary goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:400; Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 3 h, and with ABC solution (Vectorstain ABC reagent Elite Kit, Vector Laboratories) at room temperature for 1 h. DAB solution was then added for 5 min, and images were acquired using a Nikon ECLIPSE TE 2000-U microscope (Nikon).

Morris water maze (MWM) analysis

MWM analysis was performed as previously described (Shukitt-Hale et al., 2007). MWM is commonly used to examine impairment of spatial learning and memory and requires mice to find a hidden platform (10 cm in diameter) just below the surface (2 cm) of a circular pool of water (120 cm in diameter × 32 cm deep, maintained at 23°C) based on distal cues learnt during previous learning trials. Accurate navigation to the platform is rewarded by escape from the water. The maze is placed in a room with dimmed lights and numerous extra maze cues on its walls. After irradiation and baicalein treatments, mice were given five consecutive days of training in the MWM (six trials per day). At the beginning of each trial, mice were immersed in the water, facing the wall, at one of three randomized start positions (located in the centre of a pool quadrant not containing the platform). Each mouse was allowed 60 s to find the platform; if a mouse failed to escape within this time, it remained there for 5 s. At the end of trials, mice were towel-dried and returned to their home cage for approximately 30 min before being returned to the maze for subsequent trials. Performances were videotaped and analyzed using image tracking software, which calculated times taken (latencies) to find the platform (s), path lengths (cm) and swimming speeds (cm s−1), and which provided information during probe trials (after platform removal), such as the number of times the quadrant containing the platform was crossed the total time spent in this quadrant (Noldus EthoVision® XT, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, the Netherlands).

Passive avoidance test

Passive avoidance learning memory was examined using the step-through test, which takes advantage of the natural preference of mice for a dark environment. The apparatus consists of illuminated (bright) and dark compartments. During the learning stage, mice were placed in the bright compartment and received an electric foot shock (0.25 mA, 3 s) on entering the dark compartment. During the next days, mice were placed in the bright compartment for a maximum of 300 s, and times taken to enter the dark compartment (step-through latencies) were measured. For mice that did not enter the dark compartment within the 5 min observation period, step-through latency was taken to be 300 s.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± SE. One-way anova with Fisher's protected least significant difference (PLSD) procedure was used to determine the significances of differences between the irradiated and baicalein-treated groups. Statview® software (Cary, NC, USA) was used throughout, and P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Materials

Baicalein (5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone) and 2-[4,5-dimethyl-2-ly]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 2′-7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA), Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide (PI) were supplied by Invitrogen (Eugene, OR, USA). 5′-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was obtained from Acros Organics (Morris Plains, NJ, USA).

Results

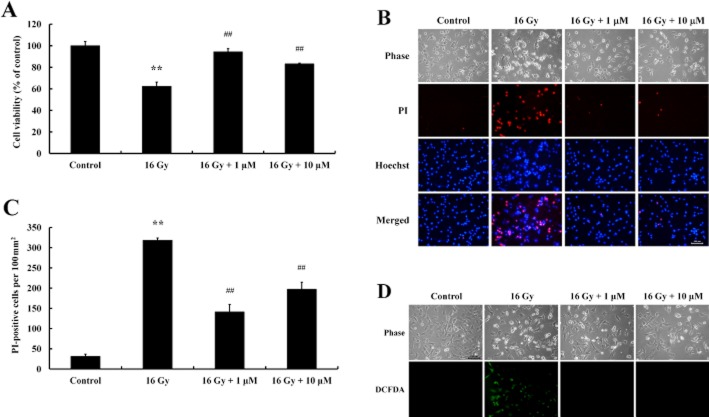

Baicalein protected C17.2 NPCs against γ-ray radiation

In a preliminary experiment, we evaluated the effects of various radiation doses (0, 2, 4, 8 and 16 Gy) on the viability of cultured C17.2 NPCs. At 24 h after a single dose of radiation, cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI and observed under a fluorescence microscope. Radiation caused cell death in a concentration-dependent manner, characterized by increased numbers of PI-positive cells, and at 16 Gy induced significant cell death (Supplementary Figure S1). MTT analysis showed that baicalein pretreatment significantly increased cell viability (Figure 1A). In addition, irradiation-induced morphological changes in C17.2 NPCs were assessed by Hoechst 33342 and PI staining. Significant increases in the numbers of PI-stained cells were observed after exposure to radiation and baicalein was reduced the number of PI-stained cells (Figure 1B, C). As ROS generated by ionizing radiation causes cell death, the fluorescence intensity of ROS was evaluated by DCFDA staining in C17.2 NPCs. Baicalein treatment blocked ROS generation induced by irradiation (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Protective effect of baicalein on irradiation-induced cell death in C17.2 NPCs. Cells were seeded and cultured for 24 h, treated with baicalein (1 μM, 10 μM), and exposed to 16 Gy 12 h later. (A) After incubation for 24 h, cell viabilities were determined by MTT assay. Analysis showed exposure to radiation significantly decreased cell viability and that baicalein had a protective effect. Data shown are means ± SE (n = 4 cultures per group). **P < 0.01 versus controls; ##P < 0.01 versus 16 Gy (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure). (B) Irradiation-induced cell death was assessed by nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342 and PI. Increased numbers of PI-stained cells were observed after irradiation. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) PI-stained cells were quantified by counting under a fluorescence microscope. Data shown are means ± SE (n = 4 cultures per group). **P < 0.01 versus Controls; ##P < 0.01 versus 16 Gy (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure). (D) Irradiation-induced ROS generation was detected by DCFDA fluorescence. Cells were treated with baicalein (1 μM, 10 μM) for 12 h, exposed at 16 Gy for 24 h, and intracellular ROS was detected by DCFDA staining under a fluorescence microscope. Scale bar = 100 μm.

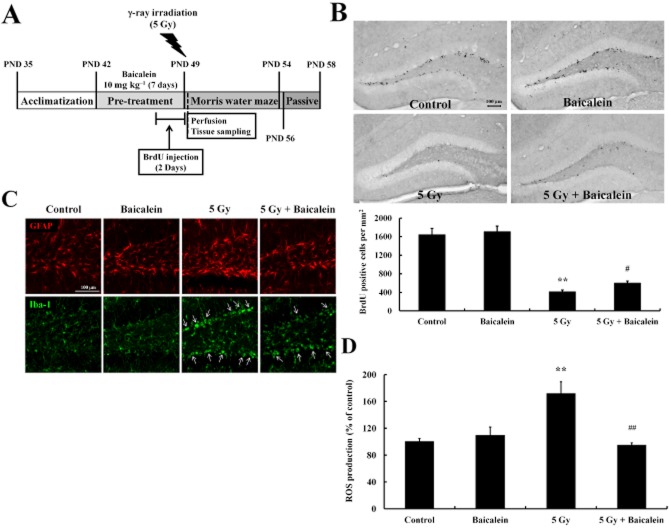

Baicalein protected NPC proliferation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus from the effects of irradiation

To investigate the neuroprotective effects of baicalein on hippocampal neurogenesis against γ-ray radiation, baicalein was administered to C57BL/6 mice once daily i.p. at 10 mg·kg−1 for 1 week, and 5 Gy of radiation was administered immediately after treatment with BrdU (Figure 2A). Proliferating cells in the hippocampus were labelled by BrdU and visualized immunohistochemically. WBI significantly decreased numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampus as compared with non-irradiated controls. Although baicalein had no effect on numbers of newly generated cells in the hippocampi of non-irradiated controls, baicalein pretreatment significantly attenuated the impaired hippocampal proliferation of NPCs induced by WBI (Figure 2B). Furthermore, double-label immunostaining with the astrocyte marker (GFAP) and the microglia cell marker (Iba-1) revealed an elevated neuroinflammatory response in the hippocampi of irradiated mice (Figure 2C). In particular, hypertrophic microglia and bushy cells (characterized by markedly enlarged soma and short, thick processes) were concentrated in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus of irradiated mice, indicating that NPCs residing in SGZ were damaged by WBI (Figure 2C, arrows). Furthermore, less activated microglia were observed in WBI treated mice pretreated with baicalein. In addition, greater GFAP immunostaining was observed in irradiated hippocampi, and this too was attenuated by baicalein (Figure 2C). Because of the antioxidative property of baicalein (Figure 1D), its effects on ROS generation in hippocampi were also analysed. As was expected, WBI increased ROS production in hippocampal homogenates, and baicalein pretreatment reduced this irradiation-induced ROS generation (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Baicalein protected NPC proliferation in the hippocampus of 6-week-old mice against WBI. (A) Scheme of the experimental procedure. (B) Representative images taken during the proliferation study showing BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus and numbers of BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) Confocal images showing qualitative differences in the expressions of GFAP (an astrocyte marker) and of Iba-1 (a microglia marker). Scale bar = 100 μm. (D) ROS generation in the hippocampus was assessed using DCFDA (see Methods). Data shown are means ± SE(n = 5 mice per group). **P < 0.01 versus Controls; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus 5 Gy (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure).

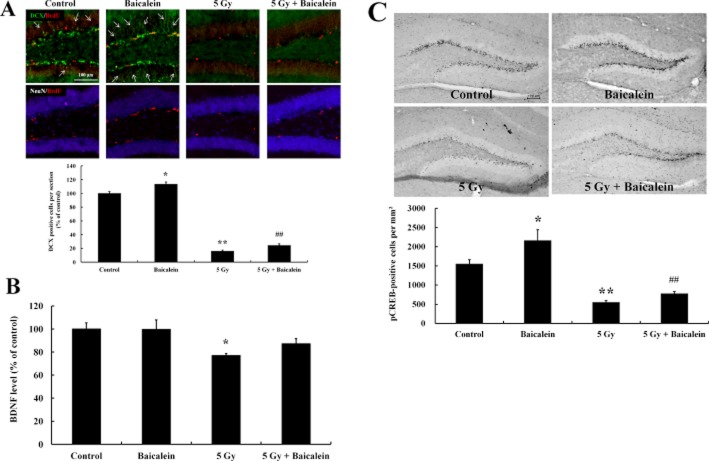

Baicalein enhanced neuronal differentiation and elevated BDNF-pCREB signalling

In order to evaluate the effects of baicalein in the neurogenic enhancement, triple-label immunohistochemistry was performed to estimate numbers of newly generated cells, using BrdU, NeuN (a mature neuron marker) and DCX (an immature neuron marker). Most BrdU-labelled cells were confined to the SGZ of hippocampi and some were co-labelled with DCX, but not with NeuN (Figure 3A). WBI dramatically decreased BrdU-positive cell numbers and DCX immunostaining, but did not affect NeuN immunostaining, indicating that NPCs are more vulnerable to irradiation. Interestingly, baicalein appeared to increase DCX staining in non-irradiated mice (Figure 3A, arrows), which suggests that baicalein has the ability to stimulate neuronal differentiation.

Figure 3.

The possible activation of a neurogenic mechanism by baicalein through the BDNF-pCREB signalling pathway. (A) To determine phenotypic statuses of newly generated cells in the dentate gyrus after irradiation and treatment with baicalein, triple-label immunohistochemistry was performed in the hippocampus. The phenotypes of newly generated cells were determined by co-labelling newly generated cells (BrdU) with DCX (an immature neuron marker) or NeuN (a mature neuron marker) in dentate gyrus. Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantitative analysis of DCX-positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control group; ##P < 0.01 versus 5 Gy irradiated group. (B) BDNF elisa was carried out in hippocampal tissue homogenates. Data shown are the means ± SE (n = 5 mice per group). *P < 0.05 versus controls (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure). (C) Representative photomicrographs of pCREB immunostaining in each group. Hippocampal sections were immunostained with pCREB antibody. Scale bar = 100 μm. Quantitative analysis of pCREB-positive cell numbers in the dentate gyrus. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 versus control group; ##P < 0.01 versus 5 Gy irradiated group.

BDNF is known to enhance hippocampal neurogenesis (Lee et al., 2002; Rossi et al., 2006; von Bohlen und Halbach, 2010), and therefore, we measured BDNF levels in hippocampal homogenates to explore the involvement of BDNF in the impairment of neurogenesis by WBI. Hippocampal BDNF levels were significantly decreased by WBI and baicalein attenuated this loss. However, baicalein-mediated up-regulation of BDNF was not observed in non-irradiated mice (Figure 3B). The cAMP response element-binding transcription factor (CREB ) is one of the transcription factors of BDNF and is known to be associated with the regulation of neurogenesis (Hwang et al., 2011; Martin and Finsterwald, 2011). We found that the phosphorylated form of CREB (pCREB) was mainly localized in the SGZ, suggesting that NPCs in the SGZ are more actively responsive to neurogenic signals than mature neurons. Furthermore, WBI reduced pCREB-positive cells, and baicalein pretreatment blocked this loss. Interestingly, baicalein elevated pCREB immunoreactivity in the SGZ of non-irradiated mice, which suggests baicalein might have neurogenic properties (Figure 3C).

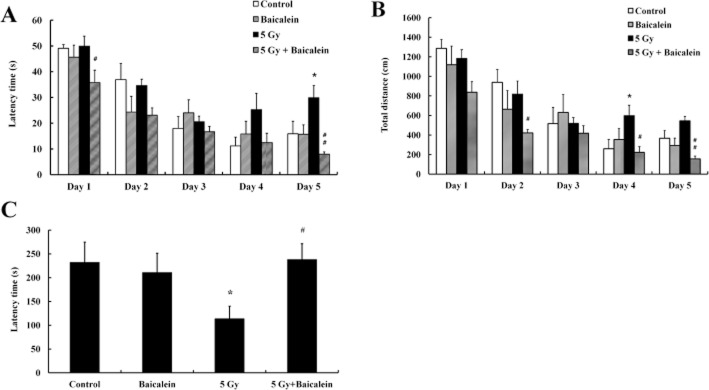

Effects of baicalein on the adverse effects of WBI on learning and memory

Hippocampal neurogenesis is often associated with hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. For example, WBI in young mice and rodents was associated with spatial cognitive deficits in the MWM (Rola et al., 2004; Shi et al., 2006). Therefore, the MWM and passive avoidance tests were used to assess spatial learning and memory, and memory retention respectively. Repeated training reduced the latencies of non-irradiated mice in the MWM test, but the latencies of irradiated mice were significantly greater. However, baicalein treatment before WBI significantly enhanced learning and memory performance relative to those in irradiated mice (Figure 4A). Similarly, baicalein pretreatment decreased swimming distance, indicating that they were more effectively found the hidden platform (Figure 4B). However, swimming velocities were unaffected by irradiation or baicalein (data not shown). Furthermore, the passive avoidance test revealed that WBI significantly reduced the step-through latencies in the passive avoidance tests, indicating that WBI impaired memory retention. More interestingly, baicalein pretreatment prevented this loss of memory retention in irradiated mice (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Effects of baicalein on hippocampal dependent cognitive function. (A–B) MWM probe trials were performed to evaluate spatial learning and memory. Latency times (A) and total distances swum (B) were analysed in mice treated with controls or baicalein with or without radiation treatment. (C) In the passive avoidance test, significant intergroup differences were found in terms of the time taken to enter the dark compartment. In particular, latencies were significantly greater for irradiated mice. Data shown are means ± SEs (n = 5 mice per group). *P < 0.05 versus controls, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 versus 5 Gy irradiated mice (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure).

Discussion

Radiation therapy is one of the most important types of therapy and is used to treat many diseases, such as, cancer and leukaemia. However, WBI is known to cause learning and memory deficits (Roman and Sperduto, 1995; Spiegler et al., 2004). In particular, children that undergo WBI suffer serious loss of neurocognitive functions (Lamproglou et al., 2002). Several authors have suggested that irradiation-induced cognitive deficits are associated with impairments of hippocampal neurogenesis (Raber et al., 2004; Rola et al., 2004) and, thus, interventional approaches are required to protect endogenous neurogenesis in the hippocampus against irradiation-induced damage. The present study showed that baicalein attenuated intracellular ROS generation and NPC death induced by γ-ray exposure, that baicalein protected hippocampal neurogenesis after WBI; and that baicalein ameliorated neurocognitive deficits caused by radiation exposure.

Because ionizing radiation increases ROS generation, intervention designed to reduce ROS generation offers a protective strategy (Gisone et al., 2004; Guelman et al., 2004) and natural polyphenolics are known to protect biosystems from irradiation-induced damage because of their antioxidant properties (Gudkov et al., 2006). Of these, the flavonoid baicalein is known to protect HT22 cells against ROS-induced cell damage and to act as an anti-inflammatory agent (Choi et al., 2010). Baicalein is a natural flavone, used in oriental medicine and shown to have a range of therapeutic effects on inflammation, cardiovascular dysfunction and bacterial infections and on cancer (Ciesielska et al., 2002; Li-Weber, 2009). Accordingly, we examined the radioprotective effects of baicalein on C17.2 NPCs, which are multi-potent NPCs isolated from neonatal mouse cerebellum (Snyder et al., 1992). C17.2 NPCs are able to differentiate into many phenotypes, such as neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes; and their proliferation is regulated by ERK and p38 kinases, similar to those of primary cultured neural stem cells (Kim et al., 2008). Several studies have reported that high concentrations of flavonoids (20 μM and above) are necessary to protect against oxidative stress-induced cell death (Chen et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011). However, in the present study, baicalein protected NPCs from irradiation-induced cell death and ROS generation at low concentrations (1–10 μM), indicating that baicalein might specifically protect cells against irradiation and/or have the ability to protect NPCs via a mechanism other than an antioxidative mechanism.

Clinically important aspects, such as safety margins and blood–brain barrier (BBB) penetrance, must be resolved for synthetic and natural therapeutics that target the brain. In a recent study, it was suggested that flavonoids (including baicalein) have a wide safety margin and are able to permeate the BBB (Shimmyo et al., 2008). As compared with post-mitotic neurons, highly proliferating cells are much more vulnerable to ionizing radiation and the adult brain is now known to have a pool of NPCs in the hippocampus (Shirai et al., 2006), and thus, radiation therapy can damage NPCs and impair hippocampal neurogenesis. In the present study, we found that 1 week of baicalein pretreatment (at 10 mg·kg−1 daily) attenuated the loss of NPC proliferation and the generation of ROS, in irradiated hippocampi. In addition, neuroinflammation within the SGZ indicated that NPCs were susceptible to irradiation and this inflammatory response was also attenuated by baicalein. Moreover, it has been already reported that baicalein suppressed NO production, iNOS protein, and NF-κB activity in microglia (Chen et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2007). Taken together, these findings suggest the radioprotective effects of baicalein are mediated by its antioxidative and anti-inflammatory properties. Furthermore, since 100 to 400 mg·kg−1 doses of flavonoids were required in previous studies for radioprotection (Qi et al., 2011; Sezer et al., 2011), our findings suggest that baicalein is highly effective at protecting adult NPCs in the hippocampus.

Interestingly, we observed that baicalein increased pCREB levels in the SGZ of the hippocampus in non-irradiated mice, which suggests that the stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis by baicalein is due in part to other than an antioxidant effect. Increased levels of BDNF and pCREB signalling reflect enhanced hippocampal neurogenesis (Lee and Son, 2009; Boneva and Yamashima, 2011). Furthermore, haplo-insufficiency in BDNF impairs basal neurogenesis in the hippocampus (Lee et al., 2002), and pCREB signalling is closely associated with hippocampal neurogenesis (Nakagawa et al., 2002). In the present study, acute WBI-induced damage was seen mainly in the SGZ based on decreases in BrdU-positive cells, DCX-staining, BDNF and pCREB signalling. These findings suggest that baicalein might act as an antioxidant to prevent loss of NPCs in the hippocampus and that this flavonoid restored impaired neurogenesis, BDNF and pCREB signalling. There are several reports proposing that baicalein elevated ERK phosphorylation in brain to initiate a downstream signalling cascade including CREB and BDNF, creating a positive feedback loop (Park et al., 2010). In addition, it was proposed that baicalein has antidepressant-like effects, which have been known to restore BDNF and enhance hippocampal neurogenesis (Neto et al., 2011; Xiong et al., 2011). Thus, it is likely that the protective effect of baicalein against radiation-induced hippocampal neurogenesis is at least partly mediated by ERK-mediated signalling pathways to induce pCREB activation and BDNF production. BDNF has been suggested to play an important role in hippocampal neurogenesis and in hippocampal-dependent forms of learning and memory (Lipsky and Marini, 2007; Lee and Son, 2009; Pardon, 2010). In the present study, WBI-induced impairments in hippocampal neurogenesis and BDNF signalling were found to be well linked with impaired learning and memory performance as determined by the MWM and passive avoidance tests. However, latencies in the MWM were still improved even in irradiated mice, which indicate that 5 Gy was not sufficient to induce detrimental neurocognitive deficits in visuospatial learning and memory. In fact, the typical radiotherapy dose administered for a solid epithelial tumour ranges from 60 to 80 Gy, whereas lymphomas are treated at 20 to 40 Gy, and preventative doses are typically around 45 to 60 Gy in 1.8 to 2 Gy fractions for brain tumours (Shibamoto et al., 2009; Thariat et al., 2010). Interestingly, during memory retention testing, most of the mice treated with baicalein and WBI stayed in the bright compartment throughout testing whereas WBI-treated mice strayed apparently unimpeded into the dark compartment. These findings suggest that baicalein protected memory from irradiation. Actually, we observed a significant loss of NPC proliferation in irradiated mice pretreated with baicalein versus non-irradiated mice, but neurocognitive functions in the MWM and passive avoidance tests were conserved by baicalein treatment, which suggests that a low level of protection might be enough to prevent irradiation-induced memory impairment.

In conclusion, the present study suggested that baicalein ameliorated the side effects of WBI, particularly with respect to hippocampal neurogenesis and memory retention, via its antioxidative property and neurogenic action. We suggest that baicalein be considered a potential prophylactic treatment to reduce impaired neurogenesis and neurocognition after WBI.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program via the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant no. 2009–0067608). This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MEST) (grant no. 20090083538). The authors thank Dr C Cepko at Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA for kindly providing the C17.2 cell line.

Glossary

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding

- NPCs

neural progenitor cells

- PI

propidium iodide

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SGZ

Subgranular zone

- WBI

whole-brain irradiation

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 C17.2 NPCs exposed to irradiation showed a dose-dependent increase in cell death.

To evaluate cell death and viability in response to irradiation, nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 and PI, and visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Radiation doses were found to be dose-dependently related to numbers of PI-stained cells (dead cells). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure S2 Detrimental effects of WBI on NPC proliferation in the hippocampi of mice. At one day after WBI, significant dose-dependent decreases were observed in the numbers of newly generated cells. (A) Representative images showing the number of BrdU-positive cells in the dentate gyrus. (B) Numbers of newly generated cells in the SGZ significantly decreased at 24 h post-WBI. WBI substantially and dose-dependently reduced proliferating cell numbers at dose from 5 to 30 Gy. Values are the means ± SE (n = 3 mice per group). **P < 0.01 versus controls (anova using Fisher's PLSD procedure). Scale bar = 100 μm.

References

- Abayomi OK. Pathogenesis of irradiation-induced cognitive dysfunction. Acta Oncol. 1996;35:659–663. doi: 10.3109/02841869609083995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achanta P, Fuss M, Martinez JL., Jr Ionizing radiation impairs the formation of trace fear memories and reduces hippocampal neurogenesis. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:1036–1045. doi: 10.1037/a0016870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bohlen und Halbach O. Involvement of BDNF in age-dependent alterations in the hippocampus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boneva NB, Yamashima T. New insights into ‘GPR40-CREB interaction inadult neurogenesis’ specific for primates. Hippocampus. 2011;22:896–905. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan BC, Ip M, Lau CB, Lui SL, Jolivalt C, Ganem-Elbaz C, et al. Synergistic effects of baicalein with ciprofloxacin against NorA over-expressed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and inhibition of MRSA pyruvate kinase. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;137:767–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CJ, Raung SL, Liao SL, Chen SY. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by baicalein in endotoxin/cytokine-stimulated microglia. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:957–965. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chua KW, Chua CC, Yu H, Pei A, Chua BH, et al. Antioxidant activity of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone provides neuroprotection against glutamate-induced toxicity. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PY, Lee YM, Wu YS, Chang TW, Jin JS, Yen MH. Protective effect of baicalein against endotoxic shock in rats in vivo and in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;73:793–804. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JH, Choi AY, Yoon H, Choe W, Yoon KS, Ha J, et al. Baicalein protects HT22 murine hippocampal neuronal cells against endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species production and CHOP induction. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42:811–822. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.12.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielska E, Gwardys A, Metodiewa D. Anticancer, antiradical and antioxidative actions of novel Antoksyd S and its major components, baicalin and baicalein. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2885–2891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossen JR, Garwood D, Glatstein E, Neuwelt EA. Neurobehavioral sequelae of cranial irradiation in adults: a review of radiation-induced encephalopathy. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:627–642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delanian S, Lefaix JL. Current management for late normal tissue injury: radiation-induced fibrosis and necrosis. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabor M. Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic properties of flavonoids. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1986;213:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gheusi G, Rochefort C. [Neurogenesis in the adult brain. Functional consequences] J Soc Biol. 2002;196:67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisone P, Dubner D, Del Perez Rosario M, Michelin S, Puntarulo S. The role of nitric oxide in the radiation-induced effects in the developing brain. In Vivo. 2004;18:281–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudkov SV, Shtarkman IN, Smirnova VS, Chernikov AV, Bruskov VI. Guanosine and inosine display antioxidant activity, protect DNA in vitro from oxidative damage induced by reactive oxygen species, and serve as radioprotectors in mice. Radiat Res. 2006;165:538–545. doi: 10.1667/RR3552.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelman LR, Pagotto RM, Di Toro CG, Zieher LM. Deferoxamine antioxidant activity on cerebellar granule cells gamma-irradiated in vitro. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang IK, Yoo KY, Yoo DY, Choi JW, Lee CH, Choi JH, et al. Time-course of changes in phosphorylated CREB in neuroblasts and BDNF in the mouse dentate gyrus at early postnatal stages. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2011;31:669–674. doi: 10.1007/s10571-011-9686-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabakov AE, Kudryavtsev VA, Gabai VL. Determination of cell survival or death. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;787:231–244. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-295-3_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang KA, Zhang R, Piao MJ, Chae S, Kim HS, Park JH, et al. Baicalein inhibits oxidative stress-induced cellular damage via antioxidant effects. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;28:412–421. doi: 10.1177/0748233711413799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Son TG, Park HR, Park M, Kim MS, Kim HS, et al. Curcumin stimulates proliferation of embryonic neural progenitor cells and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:14497–14505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708373200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laack NN, Brown PD. Cognitive sequelae of brain radiation in adults. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:702–713. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamproglou I, Baillet F, Boisserie G, Mazeron JJ, Delattre JY. [The influence of age on radiation-induced cognitive deficit: experimental studies on brain irradiation of 30 gy in 10 sessions and 12 hours in the Wistar rat at 1 1/2, 4 and 18 months age] Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2002;80:679–685. doi: 10.1139/y02-077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Son H. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and related neurotrophic factors. BMB Rep. 2009;42:239–244. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.5.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Duan W, Mattson MP. Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for basal neurogenesis and mediates, in part, the enhancement of neurogenesis by dietary restriction in the hippocampus of adult mice. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1367–1375. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Lu SS, Wang AX, Qi XY, Zhao D, Wang ZH, et al. Apigenin attenuates dopamine-induced apoptosis in melanocytes via oxidative stress-related p38, c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt signaling. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky RH, Marini AM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neuronal survival and behavior-related plasticity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:130–143. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ML, Yu LC. Potential protection of green tea polyphenols against ultraviolet irradiation-induced injury on rat cortical neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2008;444:236–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Weber M. New therapeutic aspects of flavones: the anticancer properties of Scutellaria and its main active constituents Wogonin, Baicalein and Baicalin. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Finsterwald C. Cooperation between BDNF and glutamate in the regulation of synaptic transmission and neuronal development. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:14–16. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.13761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reportingexperiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monje ML, Palmer T. Radiation injury and neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:129–134. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000063772.81810.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motomura K, Ogura M, Natsume A, Yokoyama H, Wakabayashi T. A free-radical scavenger protects the neural progenitor cells in the dentate subgranular zone of the hippocampus from cell death after X-irradiation. Neurosci Lett. 2010;485:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S, Kim JE, Lee R, Chen J, Fujioka T, Malberg J, et al. Localization of phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein in immature neurons of adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9868–9876. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09868.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto FL, Borges G, Torres-Sanchez S, Mico JA, Berrocoso E. Neurotrophins role in depression neurobiology: a review of basic and clinical evidence. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9:530–552. doi: 10.2174/157015911798376262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardon MC. Role of neurotrophic factors in behavioral processes: implications for the treatment of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders. Vitam Horm. 2010;82:185–200. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(10)82010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HR, Lee J. Neurogenic contributions made by dietary regulation to hippocampal neurogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1229:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kim DH, Kim JM, Shin CY, Cheong JH, Ko KH, et al. Mismatch between changes in baicalein-induced memory-related biochemical parameters and behavioral consequences in mouse. Brain Res. 2010;1355:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein RD, Higuchi Y, Moldovan M, Johnson K, Fukuda S, Gridley DS, et al. Metalloporphyrin antioxidants ameliorate normal tissue radiation damage in rat brain. Int J Radiat Biol. 2010;86:145–163. doi: 10.3109/09553000903419965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TM, Winblad B, Granholm AC, Mohammed AH. Environmental influences on brain neurotrophins in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;73:167–175. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L, Liu CY, Wu WQ, Gu ZL, Guo CY. Protective effect of flavonoids from Astragalus complanatus on radiation induced damages in mice. Fitoterapia. 2011;82:383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raber J, Rola R, LeFevour A, Morhardt D, Curley J, Mizumatsu S, et al. Radiation-induced cognitive impairments are associated with changes in indicators of hippocampal neurogenesis. Radiat Res. 2004;162:39–47. doi: 10.1667/rr3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rola R, Raber J, Rizk A, Otsuka S, VandenBerg SR, Morhardt DR, et al. Radiation-induced impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis is associated with cognitive deficits in young mice. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:316–330. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman DD, Sperduto PW. Neuropsychological effects of cranial radiation: current knowledge and future directions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:983–998. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00550-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi C, Angelucci A, Costantin L, Braschi C, Mazzantini M, Babbini F, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is required for the enhancement of hippocampal neurogenesis following environmental enrichment. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1850–1856. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupnow BA, Knox SJ. The role of radiation-induced apoptosis as a determinant of tumor responses to radiation therapy. Apoptosis. 1999;4:115–143. doi: 10.1023/a:1009675028784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sezer A, Usta U, Kocak Z, Yagci MA. The effect of a flavonoid fractions diosmin + hesperidin on radiation-induced acute proctitis in a rat model. J Cancer Res Ther. 2011;7:152–156. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.82927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Adams MM, Long A, Carter CC, Bennett C, Sonntag WE, et al. Spatial learning and memory deficits after whole-brain irradiation are associated with changes in NMDA receptor subunits in the hippocampus. Radiat Res. 2006;166:892–899. doi: 10.1667/RR0588.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibamoto Y, Sugie C, Iwata H. Radiotherapy for metastatic brain tumors. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:281–288. doi: 10.1007/s10147-009-0915-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimmyo Y, Kihara T, Akaike A, Niidome T, Sugimoto H. Flavonols and flavones as BACE-1 inhibitors: structure-activity relationship in cell-free, cell-based and in silico studies reveal novel pharmacophore features. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai K, Mizui T, Suzuki Y, Kobayashi Y, Nakano T, Shirao T. Differential effects of x-irradiation on immature and mature hippocampal neurons in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2006;399:57–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukitt-Hale B, Carey AN, Jenkins D, Rabin BM, Joseph JA. Beneficial effects of fruit extracts on neuronal function and behavior in a rodent model of accelerated aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder EY, Deitcher DL, Walsh C, Arnold-Aldea S, Hartwieg EA, Cepko CL. Multipotent neural cell lines can engraft and participate in development of mouse cerebellum. Cell. 1992;68:33–51. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90204-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegler BJ, Bouffet E, Greenberg ML, Rutka JT, Mabbott DJ. Change in neurocognitive functioning after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:706–713. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas NR. Baicalin, an emerging multi-therapeutic agent: pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and considerations from drug development perspectives. Xenobiotica. 2010;40:357–367. doi: 10.3109/00498251003663724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thariat J, Marcy PY, Lagrange JL. [Trends in radiation therapy for the treatment of metastatic and oligometastatic disease in 2010] Bull Cancer. 2010;97:1467–1476. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2010.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Jiang B, Wu PF, Tian J, Shi LL, Gu J, et al. Antidepressant effects of a plant-derived flavonoid baicalein involving extracellular signal-regulated kinases cascade. Biol Pharm Bull. 2011;34:253–259. doi: 10.1248/bpb.34.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T, Goto S, Kawakatsu M, Urata Y, Li TS. Mitochondrial dysfunction, a probable cause of persistent oxidative stress after exposure to ionizing radiation. Free Radic Res. 2011;46:147–153. doi: 10.3109/10715762.2011.645207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Kang KA, Kang SS, Park JW, Hyun JW. Morin (2′,3,4′,5,7-pentahydroxyflavone) protected cells against gamma-radiation-induced oxidative stress. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;108:63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2010.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.