Abstract

Objectives

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), has provoked much controversy and led to arguments between the medical profession and patient organizations. A particular focus for debate is the categorization of the condition as physical or psychological in its nature. The aim of this study was to compare how the written media, patient organizations and medical authorities regard the illness.

Design

Content analysis of newspaper articles, ME patient organization websites, and medical websites and textbooks were assessed by two independent assessors.

Setting

Three national UK newspapers, UK ME websites, and UK medical websites and textbooks, were accessed during 2010.

Participants

146 source files were scored from 36 patients' organizations, 72 media articles and 38 medical authorities.

Main outcome measured

The overall opinion of an article or website was rated using a five point Likert scale, from ‘extremely psychological’ (scored as 1), ‘moderately psychological’ (2), ‘both psychological and physical’ (3), ‘moderately physical’ (4) or ‘extremely physical’ (5).

Results

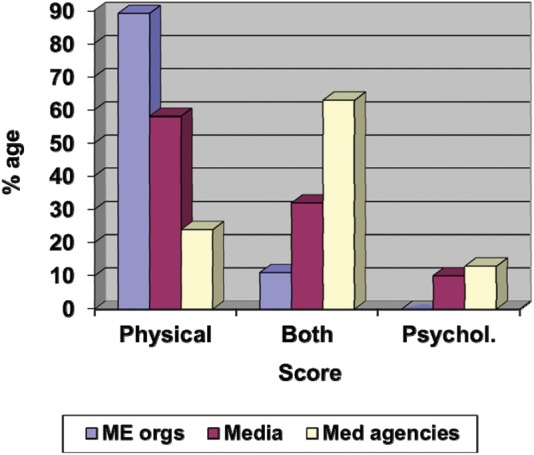

Eighty-nine percent (32 of 36) of ME patient organizations considered the illness to be physical, compared with 58% (42/72) of newspaper articles, and 24% (9/38) of medical authorities. Sixty-three percent (24/38) of medical authorities regarded the illness as both physical and psychological. The inter-group differences of the Likert scores were statistically significant (χ2 = 27.37, 2 df, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The considerable disagreement, particularly between ME patient organizations and medical authorities, may help to explain the gulf in understanding between doctors and patients and the consequent reluctance of some patients to engage in behavioural treatments.

Introduction

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), has been in the media spotlight because of the many controversies that it has created. One of the keenest debates is whether CFS/ME is a physical disease, a psychological illness or a condition that has both these components. CFS/ME is a condition that manifests itself with both physical and psychological symptoms.1 There is no diagnostic test available and the pathogenesis is unknown. The various opinions put forward have created controversy and emphasized mind–body dualism. This concept, first introduced by Plato and later misattributed to Descartes, suggests disunion between body and mind, and the illnesses affecting each. Moreover, there has been an old but strong view that diseases of the body are ‘real’, whereas illnesses of the mind are not.

One of the important historical challenges with regards to CFS/ME was to define and delineate the illness. This has proved to be difficult. It was only in 2002 that CFS/ME was recognized as a chronic disabling condition in the UK by the Department of Health.2 The confusion regarding whether the nature of the illness is physical or psychological is exemplified by the way it is classified. WHO have classified ME under the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 (G93.3) as a neurological disease.3 The same classification suggests that a ‘fatigue syndrome’ should be classified as ‘neurasthenia’ (F48.0) in the mental and behavioural disorders chapter.3 While the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has not adopted either of these classifications, NICE does state that CFS/ME is a chronic and disabling condition that manifests itself with various symptoms ranging from fatigue, malaise, headaches, sleep disturbance, poor concentration and muscle pain.1

Another subject of debate is naming the condition. Since its existence, CFS/ME has received several names – myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), post-viral fatigue syndrome, post-infectious fatigue syndrome and chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS). Some patient groups and clinicians argue that CFS diminishes the legitimacy of the illness compared with the label of ME. In the last fifteen years CFS/ME has gained recognition by the UK Department of Health, NICE and several UK Royal Colleges of medicine.1,2,4

The aim of this study was to examine the extent to which CFS/ME is viewed as either physical or psychological by the media, patient organizations and the medical establishment. This question is important since it affects the attitudes and beliefs of health professionals, patients and the general public. Disagreement with respect to the various views and opinions expressed by these groups can have repercussions on acceptance of treatment, research funding and the attitudes of others towards patients.

Methods

Searches

We studied three different sources of opinion: the newspaper media, patient advocates and medical authorities. For each data source, the following search terms were used: myalgic encephalomyelitis, myalgic encephalopathy, ME, chronic fatigue syndrome, CFS, post-viral fatigue syndrome, PVFS and post-infectious fatigue syndrome.

Media

To gather the opinions expressed by the media regarding CFS/ME, three newspapers were chosen: The Daily Mail (politically right of centre tabloid), The Guardian (left of centre broadsheet) and The Daily Telegraph (right of centre broadsheet). Articles published between 2007 and 2009 were assessed.

Patient organizations

CFS/ME organizations were selected to represent patient advocates’ views. A Google search was done for CFS/ME organizations in the UK. We assessed both national and local ME organizations, so long as they had a website. The Welsh Association of ME & CFS Support website,5 the Healthy ME website6 and the Partnership for Research in CFS and ME (PRIME)7 websites provided a valuable list of CFS/ME organizations (available from the authors on request).

Medical authorities

The medical authorities that we assessed were organizations, which included NICE, NHS Plus, NHS 24, NHS Choices, Department of Health and Royal Colleges of General Practitioners, Paediatrics and Child Health, Physicians and Psychiatrists. In each of their websites, CFS/ME was entered in the search engine and where an appropriate result was produced, the relative Royal College was entered as part of the data source.

The second source of medical authorities was medical textbooks, selected from the range available at Barts and The London Medical School's library. Books under the headings ‘general medicine’ and ‘general psychiatry’ were selected. Furthermore, the recommended reading list was obtained from Bart's and The London Medical School. This inferred that these books would also be used by the other medical schools and helped to justify the final list of books (available from the authors on request).

Scoring

All the information was scored using a five point Likert scale from a score of 1 (extremely psychological) through to a score of 5 (extremely physical) (Figure 1), which was revised after pilot work. The overall impression regarding the nature of CFS/ME that was given by the three sources of information was scored by two independent raters (the authors). The arguments or opinions that were given in favour of CFS/ME being a ‘physical’ or ‘psychological’ condition were balanced as accurately as possible. For example, two arguments for ‘physical’ and one argument for ‘psychological’ got a score of 4. The two independent raters’ scores were later compared and where there was a discrepancy, a mean of both scores was used for that entry. No weighting was used, so that each source was regarded as equally valid and counting towards the overall score for that domain. No ethical permission for the study was sought, since no personal data were obtained and all information used was publically available.

Figure 1.

Likert scores used by raters

Data analysis

The SPSS Statistics software version 16 was used to analyse the data. The inter-rater agreements were given and a kappa score was derived for them. Since the distributions were not normally distributed, descriptive statistics were median and interquartile range, with comparisons made by Kruskall–Wallis test for all three groups and Mann-Whitney U test for pair comparisons. In order to clarify the differences, we categorized the Likert scores into three groups: ‘physical’ view taken as all scores greater than 3.5, ‘both physical and psychological’ as a score of between 2.5 and 3.5 inclusive, and ‘psychological’ as those scores less than 2.5.

Results

A total of 146 source files were scored from 36 patients’ organizations, 72 media articles and 38 medical authorities. The two independent raters gave exactly the same score for 82 (56%) of the entries, one unit score apart for 55 (37%) of the entries and two unit scores apart for ten (7%) of entries. The kappa score for inter-rater agreement was 0.314.

The median (interquartile range) scores for patient organizations was 4.5 (4–5), 4 (3–4.5) for the media and 3.5 (2.9–3.6) for medical authorities. The Kruskall–Wallis test showed a statistically significant difference in distributions among the different groups (χ2 = 27.37, 2 df, P < 0.001) with a mean rank of 100 for patient organization, 73 for media and 50 for medical authorities. There were also significant differences when the groups were compared with each other: patient organizations versus medical authorities (U = 203, P < 0.001), patient organizations versus media (U =819, P = 0.001) and medical authorities versus media (U =935, P = 0.006).

The individual categorized scores are given in (Figure 2). For ME organizations, 32/36 entries (89%) were rated physical, 4 (11%) were rated both and none psychological. For newspapers, 42/72 (58%) articles were judged physical, 23 (32%) both and 7 (10%) psychological. For medical authorities, 9/38 (24%) were judged physical, 24 (63%) both and 5 (13%) psychological.

Figure 2.

Categorized ratings of nature of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis

Discussion

We found a significant discrepancy between views of the nature of CFS/ME expressed by different authorities, with the greatest discrepancy being between patient organizations, almost all of which regarded the illness as physical and medical authorities, where the majority considered the illness as both physical and psychological.

The limitations of this study include the inability of the raters to be blinded to the source, the moderate size of the agreement between raters, with this being ameliorated by relying on mean scores where disagreement arose. It may be that the views in the period of 2007–2010 are not applicable to current times, although recent papers would suggest that this is not the case.8 The strengths include the inclusion of all available UK patient organizations with websites, using several newspapers with a spread of political views and sourcing both medical websites and textbooks. This is the first study to compare beliefs across different authorities.

There have been few studies of attitudes towards CFS/ME. Knudsen et al.9 showed that Norwegian newspapers promoted alternative treatments more than evidence-based behavioural treatments, which would be consistent with our findings. Moreover, MacLean and Wessely found that 69% of national newspapers and women's magazines published in the 1980s and early 1990s favoured organic causes for CFS/ME which they considered reinforced dissatisfaction with traditional medical authorities.10 A survey of members of the Association of British Neurologists showed that 84% did not see the illness as a neurological one despite ME being classified as a neurological condition,11 a view more extreme than that we found for medical authorities.

These results support the view that there is a spectrum of opinions regarding the nature of the illness. It comes as no surprise that ME organizations view the condition as being physical. Many of the websites campaign to ‘….swing the pendulum back to much-needed physical research into the nature and causes of ME – and help bring forward the day when there are reliable diagnostic tests and even a cure for this illness’.12 Patient groups argue against any view that CFS/ME is anything but a physical condition.13 These views can be extreme. For instance, an article titled ‘Realpolitik and ME’ states that there is a campaign to ‘de-construct the neurological illness ME’, to ‘ridicule its sufferers’ and to ‘redefine a growing body of mentally ill subjects’.13 The same group have claimed that CFS/ME sufferers are victims of a political campaign of disinformation in an attempt to label a physical disease as the product of erroneous psychiatric belief.14 Another article questions whether sufferers should engage with ‘highly controversial and harmful psychosocial approaches’.15 This contrasts with our finding that only 13% of medical authorities regard the illness as psychological. Few patient organizations supported the NICE guidelines on management, which recommend the behavioural treatments of cognitive behaviour therapy and graded exercise therapy.1

The results obtained from the written media show that CFS/ME, which was once branded as ‘yuppie flu’, is now generally reported as a physical condition. Our finding that 58% of media articles espoused physical explanations is broadly similar to the 69% of media articles with physical explanations found some 30 years ago, suggesting that little has changed.10 Several articles, summarizing the findings of research, described a self-diagnostic urine test (testing metabolites related to hydrogen sulfide production) and also claimed that the condition was transmissible.16 In 2009 several articles featured the novel finding of a strong association between CFS and the XMRV retrovirus. These articles contributed significantly to the overall ‘physical’ scores for the media.17 Although these articles and the study provided hope for many, the results were not replicated in other centres around the world and the association is now thought to be a laboratory contamination.18

The overall opinion of medical authorities was more evenly spread between physical and psychological explanations, despite our survey including both psychiatric and medical textbooks. The most popular view was that CFS/ME was both physical and psychological. Only a minority (13%) regarded the illness as psychological.

Trying to categorize illnesses into either biological or psychological models has created division among healthcare professionals, patients and their advocates. This division simply creates unnecessary arguments instead of consensus. The concern that the condition should not be perceived as psychological has driven some healthcare professionals and many patient organizations away from supporting effective behavioural treatments. This illustrates the importance of the biopsychosocial model, first expressed by George Engel.19 The advantage of this model is that it incorporates both mind and body approaches to the benefit of the patient.1,20 The main problem of regarding the illness as purely physical is that it may produce a nocebo effect to behavioural treatments, and discourages patients to engage with these treatments, which have now been shown to be safe and moderately effective.21 This is particularly important because doctors use ME organizations and the media as their main source of information.22

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the different opinions that various groups hold regarding the nature of CFS/ME. CFS/ME is yet another condition that illustrates the importance of adopting the biopsychosocial model in our way of thinking;20 body and mind are indivisible and one can intimately affect the other.23 The origin of CFS/ME may be complex; however, the stepping stone to progress and consensus may lie in replacing the concept of mind–body dualism with a more monistic view.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

PDW has done consultancy work for the Departments of Health, Work and Pensions and a re-insurance company. ZH declares no competing interests

Funding

None declared

Ethical approval

None required

Guarantor

PDW

Contributorship

ZH and PDW conceived the idea, wrote the protocol, assessed and analysed the data and wrote the paper. ZH collected the data. Both authors approved the final version of the paper.

Reviewer

Simon Wessely

References

- 1.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy). Diagnosis and Management of CFS/ME in Adults and Children. London: NICE, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.CFS/ME Working Group A report of the CFS/ME Working Group: Report to the Chief Medical Officer of anIndependent Working Group. London: Department of Health, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders; Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Royal Colleges Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Report of a Joint Working Group of the Royal Colleges of Physicians, Psychiatrists and General Practitioners London: Roy Coll Physicians, CR54, 1996

- 5.UK ME Organisations UK ME organisations. See http://www.wames.org.uk/prydeinig.html (last accessed November 2010)

- 6.HealthME ME/CFS Links. See http://www.healthyme.co.uk/links/mecfs_links.phtml (last accessed November 2010)

- 7.PRIME- Partnership for research in CFS and ME ME/CFS Organisations and Voluntary Groups involved in PRIMEProject. See http://www.prime-cfs.org/mod_product/uploads/PRIME_ME_CFS_groups_Nov05.pdf (last accessed December 2010)

- 8.Hawkes N Dangers of research into chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ 2011;342:d3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knudsen AK, Omenas AN, Harvey SB, et al. Chronic fatigue syndrome in the media: a content analysis of newspaper articles. J R Soc Med Sh Rep 2011;2:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacLean G, Wessely S Professional and popular views of chronic fatigue syndrome. BMJ 1994;308:776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wojcik W, Armstrong D, Kanaan R ‘Is chronic fatigue syndrome a neurological condition? a survey of UK neurologists’ J Psychosom Res 2011;70:573–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ME Association ‘Just Four Quid’ Appeal for PhysicalResearch. 2009. See http://www.meassociation.org.uk/index.php?option=com_content (last accessed November 2010)

- 13.The One Click Group Realpolitik and ME. 2005 See http://www.theoneclickgroup.co.uk/documents/ME-CFS_pol/Realpolitik and ME.doc (last accessed October 2010)

- 14.The One Click Group ME/CFS Politics in aNutshell (UK) See http://theoneclickgroup.co.uk/documents/ME-CFS_docs/ME-CFS POLITICS IN A NUTSHELL UK.doc (last accessed December 2010)

- 15.The One Click Group How To Solve A Problem Like ME/CFS: Why The Gibson Report Has Failed Patients. 2006. See http://www.theoneclickgroup.co.uk/documents/ME-CFS_pol/Lara Response - Gibson Report.pdf (last accessed January 2011)

- 16.The Telegraph ME: Proof that it isn't all in the Mind? 2009. See http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/5407749/ME-Proof-that-it-isnt-all-in-the-mind.html (last accessed December 2010)

- 17.Lombardi VC, Ruscetti FW, Das Gupta J, et al. Detection of an infectious retrovirus, XMRV, in blood cells of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Science 2009;326:585–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson MJ, Erlwein O, McClure MO Xenotropic murine leukaemia virus-related virus (XMRV) does not cause chronic fatigue. Trends Microbiol 2011;19:525–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Engel GL The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. J Med Phil 1981;6:101–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White PD (editor). Biopsychosocial Medicine: An IntegratedAapproach to UnderstandingIillness. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 21.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet 2011;377:823–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chew-Graham CA, Cahill G, Dowrick C, et al. Using multiple sources of knowledge to reach clinical understanding of chronic fatigue syndrome. Ann Fam Med 2008;6:340–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White PD, Rickards H, Zeman AZJ Time to end the distinction between mental and neurological illnesses. BMJ 2012;344:e3454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]