Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive inflammatory syndrome that results from inappropriate activation of the immune system. HLH has a high mortality if not treated. We describe a case of a fulminant HLH, associated with a reactivation of an EBV infection. The patient responded well to steroid treatment.

Keywords: Epstein–Barr, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, reactivated infection, steroid treatment

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive inflammatory syndrome with high mortality that results from inappropriate activation of the immune system (lymphocytes and macrophages). HLH appears to affect all ages, although the hereditary and sporadic cases are reported more often in children (1). The incidence of HLH in Sweden has been estimated to 1.2 children per 1 million children per year, or 1 in 50,000 live births with equal sex distribution (2).

Patients with HLH can have signs and symptoms similar to a severe infection with fever, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and jaundice (3,4). In these patients, an intense inflammatory response has been shown, with high production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interferon, tumor necrosis factor, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, and soluble IL-2 receptor (sCD25) and an inappropriate activation of T cells and macrophages. The high cytokine cascade may lead to multi-organ failure and death (1).

Laboratory tests show cytopenias, hypertriglyceridemia, elevation of ferritin, alteration of hepatic enzymes, signs of hemolysis with hyperbilirubinemia and elevation of lactate dehydrogenase, and alterations of the coagulation system with low fibrinogen and disseminated intravascular coagulation (4).

The histopathological signs include hemophagocytosis in bone-marrow, spleen, and in lymph nodes with activated macrophages that engulf mature blood cells and their precursors. Diagnostic criteria include clinical and laboratory findings (3).

There is a relationship between acute and chronic EBV infections and development of HLH (5). Most described cases of EBV–HLH are reported in children and adolescents with a majority in East Asia (6).

HLH can also be secondary to other conditions, such as autoimmune disorders (adult-onset of Still's disease) (7), malignancies (particularly T cell lymphomas) (8), viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections (4), or immunosuppression (9).

Patients with X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome, a rare disorder that affects males, can develop HLH after infection by the Epstein–Barr virus (10).

This case report describes the clinical course and treatment in a patient with HLH caused by a reactivated EBV infection.

Case report

The patient was a 60-year-old woman with tablet-treated diabetes mellitus who presented with fever, pain in the throat, and a skin rash. In primary care she received antibiotics due to high CRP and sedimentation rate (SR). The fever persisted, and the patient was admitted to hospital. Concentrations of inflammatory variables (P-CRP and B- leukocytes) were high, and on suspicion of underlying bacterial infection the patient received intravenous antibiotic with cefotaxime without response. Due to deterioration with low systolic blood pressure, confusion, an intensive skin rash on arms, legs, and chest/abdomen, and fever she was admitted to the intensive care unit. Blood plasma test showed a high ferritin level of 145,000 (8–140 µg/L), and Still's disease was suspected.

Further blood/plasma tests showed signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) with high Protrombinkomplex International Normalized Ratio (PK-INR), high activated partial thromboplastin time (APT), elevated fibrin D-dimers, and successively low fibrinogen. The patient had high CRP (237 mg/L) and blood sedimentation rate (110 mm/h), anemia (89 g/L), thrombocytopenia (70 × 109/L), and leukopenia (3.1 × 109/L). Procalcitonin was 35 µg/L, which is 700 times higher than normal. The initial antibiotic treatment was changed to meropenem, gensumycin, and fluconazole. Despite treatment with antibiotics and antifungal medication, no significant improvement was seen.

Additional blood plasma tests showed high triglyceride values and soluble CD25R (IL-2R-alpha) exceeded 2,400 kU/L, indicating a high cytokine production. The patient had five of eight criteria for HLH, and thereby the diagnosis was confirmed.

Several biopsies were performed in order to find an underlying disease without success. Bone-marrow biopsy showed slight alterations of maturity in megakaryocytes and erythropoiesis and no signs of lymphoma or other malignancies. An initial phase of myelodysplastic syndrome could not be excluded, but later bone-marrow biopsies could not confirm that diagnosis. Biopsy of the skin showed non-specific inflammation with edema and infiltrations of lymphocytes round blood vessels. There were no signs of vasculitis, necroses, or granulomas.

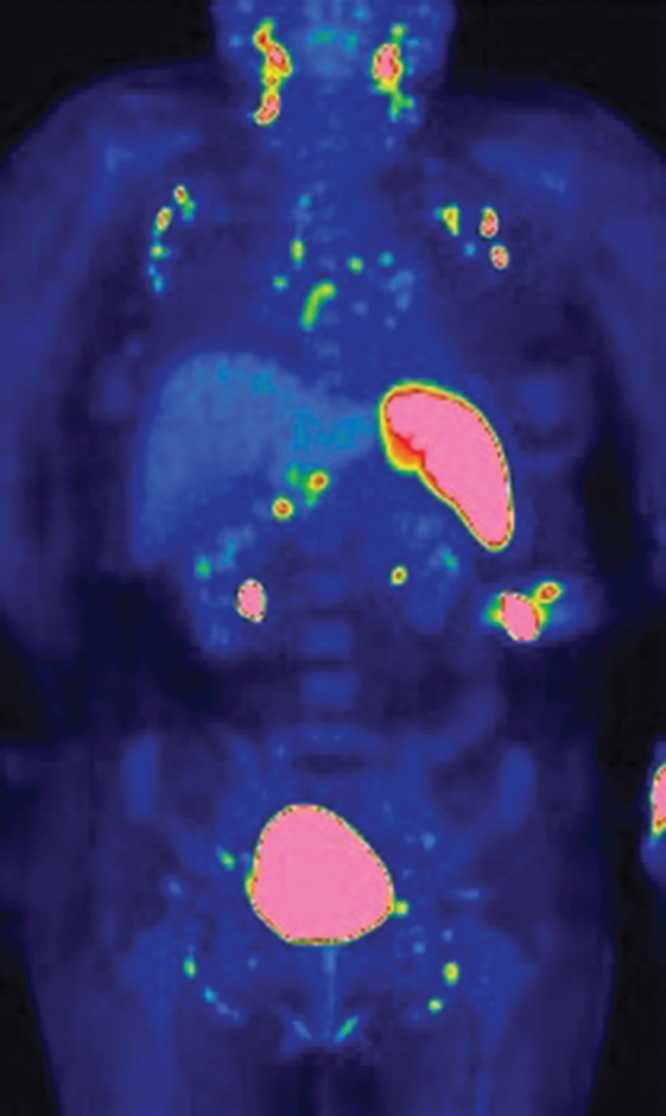

An 18F-FDG PET/CT scan was performed, in order to evaluate a possible enhanced uptake reflecting an augmented metabolism typical for e.g. malignancy. The scan showed symmetrical and bilateral uptakes in the lymph nodes of the neck, mediastinum, lung hili, liver hilum, along a. iliaca externa and inguinal regions, and in the spleen (Figure 1). The uptake was strongest in the lymph nodes of the neck and in the spleen.

Figure 1.

FDG PET/CT scan shows a symmetrical uptake in FDG-positive lymph nodes at the neck, supraclavicular fossa, axillary fossa, mediastinum, liver hilum, and along the iliaca vessels. Fused FDG PET/CT coronal image shows that the uptake correlates with bilaterally distributed lymph nodes in the axillary fossa and mediastinum, and the activated spleen is markedly increased as compared with the background FDG uptake in the liver.

We could not detect any antibodies against parvovirus B19, Human Immunodefficiency Virus (HIV), Human Immunodefficiency Virus (HHV) 6 and 8, influenza A and B, adenovirus, coronavirus, and Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) A and B. Rhinovirus, parainfluenza 1, 2, and 3, and RSV A and B in nasopharynx were negative. She had elevated IgG against HSV and Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), but was IgM-negative against both viruses.

There were no pre-existing clinical features of a background of chronic, active EBV infection. The patient had signs of previous infection from EBV by EBNA in repeated tests (presence of IgG). Despite this, the patient had an EBV load of 2,400 copies/mL in whole blood (DNA). A new assessment of EBV IgG was negative 7 days later. No bacterial or fungal infection was found despite repeated cultures from urine, blood, sputum, and bone-marrow.

According to the geneticist, the fact that our patient was a woman, 60 years old, and had no medical history of dysgammaglobulinemia or lymphoma, an X-linked proliferative syndrome was improbable. Further, the patient's age showed that a familiar form of HLH was unlikely.

The clinical presentation was not typical for morbus Still, and no other rheumatologic disease or malignancy could be confirmed.

Treatment with steroids was started first with 60 mg prednisolone and then with 16.5 mg dexamethasone. The duration of the therapy was 3 months and 17 days, and the dose was gradually decreased before the therapy was discontinued. The patient had a very good response to steroid therapy, and no treatment with etoposide or cyclosporine was necessary.

The clinical condition of the patient improved after 2 weeks of treatment with steroids. Fever disappeared, blood pressure and general condition improved, and the skin rash decreased. Hemoglobin increased from 89 g/L to 126 g/L and platelets from 70 × 109/L to 188 × 109/L within a week. Ferritin decreased from 145,000 to 18,000 µg/L in a couple of weeks.

The patient had intense fatigue in her convalescence. She was admitted to a rehabilitation unit for training, and an improvement of her general condition was gradually seen during that period. During her latest follow-up visit, the patient was feeling well, with normalized plasma ferritin and no signs of HLH activation.

Discussion

This case is one of very few reported cases with serological evidence of prior EBV infection (11). There are, however, studies showing a strong correlation with HLH and an acute EBV infection (11). The patient had a fulminant syndrome with a sepsis-like pattern, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and she needed intensive care. She was treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals without effect, but she had good clinical response to the given steroids.

It is remarkable that the patient had an extreme elevation of procalcitonin without signs of bacterial infection. That could be related to the cytokine storm secondary to the patient's disease, meaning that a condition with high production of cytokines makes it difficult to use procalcitonin to differentiate severe bacterial infections from EBV-induced HLH. The extreme elevation of plasma ferritin was typical for HLH, and the patient fulfilled criteria for HLH.

There is a well-known association between infections and development of HLH. Infections can be viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic (4). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was positive for EBV during the acute phase of the disease. This indicates that our patient reactivated a previous EBV infection, even though she had a positive EBNA.

EBV–HLH is a rare condition, but the incidence is probably underestimated due to lack of awareness of the diagnostic criteria and to the similarity between its initial clinical presentation and a wide variety of inflammatory and other infective disorders. The criteria established by Henter et al. (3) are a useful guide to diagnosis. Further, the presence of neutralizing antibodies does not exclude a reactivation of EBV with a subsequent EBV–HLH in an otherwise immune-competent individual.

A treatment protocol includes induction therapy with dexamethasone and etoposide, followed by continuous treatment with cyclosporine and pulses of dexamethasone and etoposide (12). Sometimes treatment with dexamethasone and cyclosporine is started, but etoposide can be added if necessary.

Our patient received treatment with dexamethasone with a very good clinical and laboratory response, and the addition of etoposide or cyclosporine was not necessary.

Our patient survived despite her severe clinical condition; she was diagnosed early, and proper treatment was given. No other similar cases have been reported in Sweden, to our knowledge.

Acknowledgments

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Imashuku S. Advances in the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2000;72:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henter JI, Elinder G, Soder O, Ost A. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:428–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henter JI, Elinder G, Ost A. Diagnostic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The FHL Study Group of the Histiocyte Society. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:601–8. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox CP, Shannon-Lowe C, Gothard P, Kishore B, Neilson J, O’Connor N, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults characterized by high viral genome load within circulating natural killer cells. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:66–9. doi: 10.1086/653424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elazary AS, Wolf DG, Amir G, Avni B, Rund D, Yehuda DB, et al. Severe Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in six adult patients. J Clin Virol. 2007;40:156–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumakura S, Ishikura H, Munemasa S, Adachi T, Murakawa Y, Kobayashi S. Adult onset Still's disease associated hemophagocytosis. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1645–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang CS, Wang CH, Su IJ, Chen YC, Shen MC. Hematophagic histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic analysis of 23 cases with special reference to the association with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 1994;93:421–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grateau G, Bachmeyer C, Blanche P, Jouanne M, Tulliez M, Galland C, et al. Haemophagocytic syndrome in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: nine cases and a review. J Infect. 1997;34:219–25. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(97)94227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Purtilo DT, DeFlorio D, Jr, Hutt LM, Bhawan J, Yang JP, Otto R, et al. Variable phenotypic expression of an X-linked recessive lymphoproliferative syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1077–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197711172972001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quintanilla-Martinez L, Kumar S, Fend F, Reyes E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Kingma DW, et al. Fulminant EBV(+) T- cell lymphoproliferative disorder following acute/chronic EBV infection: a distinct clinicopathologic syndrome. Blood. 2000;96:443–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Aricò M, Egeler RM, Elinder G, Filipovich AH, et al. Histocyte Society Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:2367–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]