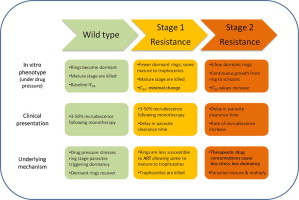

Graphical abstract

Highlights

► Artemisinin induced dormancy is a plausible cause of treatment failure. ► Dormancy is likely a parasite stress response triggered by artemisinin. ► Artemisinin resistance may develop as a 2 step process linked with dormancy. ► Step one involves ring stage resistance reflected by changes in the dormancy profile. ► Step two resistance develops due to reduced susceptibility of mature stages.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Artemisinin, Treatment failure, Dormancy, Artemisinin resistance

Abstract

Artemisinin (ART) based combination therapy (ACT) is used as the first line treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria in over 100 countries and is the cornerstone of malaria control and elimination programs in these areas. However, despite the high potency and rapid parasite killing action of ART derivatives there is a high rate of recrudescence associated with ART monotherapy and recrudescence is not uncommon even when ACT is used. Compounding this problem are reports that some parasites in Cambodia, a known foci of drug resistance, have decreased in vivo sensitivity to ART. This raises serious concerns for the development of ART resistance in the field even though no major phenotypic and genotypic changes have yet been identified in these parasites. In this article we review available data on the characteristics of ART, its effects on Plasmodium falciparum parasites and present a hypothesis to explain the high rate of recrudescence associated with this potent class of drugs and the current enigma surrounding ART resistance.

1. Introduction

Malaria is caused by the infection of Plasmodium spp. and is endemic in 106 countries causing an estimated 225 million cases and 800,000 deaths in 2009 (WHO, 2010b). This high rate of morbidity and mortality is due to the rapid growth and multiplication of the Plasmodium parasites in host red blood cells. Early and effective treatment is vital in preventing severe complications and death, and is a key element of malaria control and elimination programs.

Several decades ago malaria could be effectively treated using a variety of antimalarial drugs including chloroquine, pyrimethamine/sulfadoxine (Fansidar), mefloquine and atovaquone/proguanil (Malarone). Most of these drugs act on the relatively mature stages of parasites within erythrocytes preventing their further maturation and multiplication. In the late 1960s P. falciparum developed resistance to chloroquine and has subsequently developed resistance to most other drugs rendering them unusable in many affected areas. Antimalarial resistance resulted in increased disease burden (Zucker et al., 1996; Trape et al., 1998; Bjorkman, 2002; Tjitra et al., 2008), increased transmission (Price and Nosten, 2001) and epidemics (Warsame et al., 1990). As such, Plasmodium resistance to anti-malarial drugs has become a major obstacle in the global fight against malaria.

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended artemisinin (ART)-based combination therapies (ACTs) as first-line treatment for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, and during the past decade most malaria endemic countries have shifted their national treatment policies to ACTs (WHO, 2010a). ART and its derivatives are the most potent and rapidly acting antimalarial drugs (see reviews by Cumming et al. (1997), Gera and Khalil (1997), Li and Wu (1998), Meshnick (1998, 2002), White (1998b), Balint (2001), Haynes and Krishna (2004), Olliaro and Taylor (2004), Bray et al. (2005), Nosten and White (2007) and Ding et al. (2010). These drugs act on all asexual stages of the parasite and are able to reduce parasite biomass by up to 10,000-fold per cycle (White, 1997), thus providing rapid relief of symptoms. Importantly, this class of drug is effective against multi drug resistant parasites. ACTs also reduce the production of gametocytes and are reported to have an impact on transmission (Dutta et al., 1989; Kumar and Zheng, 1990; Price et al., 1996; Targett et al., 2001). For these reasons ACTs have become the cornerstone of current malaria control and elimination programs.

Despite the remarkable activity of ART on P. falciparum parasites, 3–50% of non-immune patients fail treatment if ART is given as a mono-therapy (Meshnick and Taylor, 1996). This wide range of treatment failure rates is mainly due to the duration of treatment, where higher failure rates were observed after 3 day treatments, decreasing for 5–7 day treatments. High parasite densities prior to treatment also contribute to increased treatment failure (Ittarat et al., 2003). It has been proposed that because ART compounds have a short elimination half-life they are not able to eliminate all parasites during the treatment, resulting in recrudescence (White, 1997; Kyle et al., 1998; Giao et al., 2001). However, increasing the treatment duration from 3–5 days to 5–7 days only reduced (Nguyen et al., 1993), but did not eliminate recrudescence (McIntosh and Olliaro, 1999; Giao et al., 2001). This result is difficult to explain based on the drugs’ potency and pharmacokinetic/dynamic properties alone. Interestingly, the parasites collected from the treatment failures after ART monotherapy are not resistant to ART in vitro (Looareesuwan et al., 1997) and retreatment is effective (de Vries and Dien, 1996; Ittarat et al., 2003). Fortunately, this high rate of recrudescence could be significantly reduced by using ART in combination with other antimalarial drugs such as mefloquine, lumefantrine, pyronaridine, and piperaquine, to form ACTs. To date the reason for the high rate of recrudescence associated with ART monotherapy and the exact mechanism by which the combinations reduce recrudescence is uncertain.

One major threat to the efficacy and useful life of ACTs would be the development of parasite resistance to ART. Recent reports of parasites in Cambodia with decreased in vivo sensitivity to artesunate (AS), an ART derivative, raises serious concerns for the development of ART resistance (Noedl et al., 2008; Dondorp et al., 2009). The clinical data from western Cambodia showed significantly longer parasite clearance times after AS mono-therapy compared to cases in north-western Thailand (Dondorp et al., 2009). No major changes in parasite phenotype, particularly in vitro IC50 values, or genotype were detected in the Cambodian parasites. This profile is different to that of other antimalarial drugs where changes in the in vitro IC50 values are usually observed in resistant parasites. While it is clear that the parasites are adapting to ART pressure, the mechanism responsible is not known. Without a phenotype or molecular marker it is difficult to monitor and contain the development of ART-resistant parasites.

Why are ART monotherapies associated with high rates of recrudescence? How do ART-combinations reduce recrudescence? What is the explanation for delayed clearance time observed in Cambodia? A better understanding of these important questions may help to protect the efficacy of ART and ACTs. In this article we review available data and present our interpretations in an effort to address these questions.

2. The main cause of recrudescence: art-induced dormancy

2.1. The hypothesis

Box 1. Definition of treatment failure (WHO, 2010a).

Treatment failure is defined as an inability to clear malarial parasitaemia or resolve clinical symptoms despite administration of an antimalarial medicine. Treatment failure is not, however, always due to drug resistance, and many factors can contribute, mainly by reducing drug concentrations. These factors include incorrect dosage, poor patient compliance in respect of either dose or duration of treatment, poor drug quality and drug interactions.

In 1996 Kyle and Webster reported that the development of early ring stage P. falciparum parasites was interrupted following exposure to AS or dihydroartemisinin (DHA), the metabolite of several members of the ART family; these parasites survived in a dormant form for 3–8 days before resuming normal growth (Kyle and Webster, 1996). This observation led them to hypothesize that some ART-treated parasites enter a state of dormancy, where they are protected from the drug’s lethal effects, but recover at a later date to resume normal growth. The phenomenon is similar to the post antibiotic effect reported in bacteria (Odenholt et al., 1997). Almost at the same time, Bwijo et al. used a repetitive dosing in vitro model to simulate the in vivo pharmacokinetics of ART. Their results indicated that exposure to ART (3 h pulses once daily) in vitro reduced the number of P. falciparum asexual parasites to very low levels, but did not completely eradicate the parasites unless ⩾10 μM ART was used (Bwijo et al., 1997). The timing of the ‘recrudescent’ growth of these cultures was related to the dose, the frequency and duration of exposure to the drug. A theoretical mathematical model of AS treatment was also proposed which included dormancy (Hoshen et al., 2000). The model output supported the dormancy hypothesis and highlighted the importance of dormancy in selecting the optimal AS treatment regimen. However more comprehensive laboratory and field evidence were required to confirm this hypothesis.

2.2. In vitro evidence

To investigate the dormancy hypothesis further in vitro studies using a single 6 h exposure to 200 ng/ml (∼7 × 10−7 M) DHA, which is comparable to the serum level of DHA in patients treated with ART derivatives, were conducted (Teuscher et al., 2010). It was found that ring stage parasite development was abruptly arrested following exposure and parasites entered a dormant state lasting up to 20 days (Teuscher et al., 2010). These dormant parasites had distinct morphological features: the vacuole is not present, the cytoplasm is condensed and tightened towards the nucleus and the nucleus is condensed. Although the great majority of these parasites die in this state, a proportion recovered to become growing parasites with a normal morphology between 3 and 20 days post-treatment. The overall recovery rate from dormancy was estimated to be between 0.044% and 1.313%, dependent on parasite line and treatment dose (Teuscher et al., 2010). Approximately 50% of dormant parasites that recovered resumed growth within 9 days of treatment. Using this experimental system the authors demonstrated that dormancy can be readily induced in ring stage P. falciparum. Furthermore, the authors observed that repeated treatment with DHA for 3 consecutive days, 6 h per day, reduced the recovery rate by 10-fold highlighting the importance of using a prolonged ART treatment regimen.

2.3. How do ACTs work to reduce recrudescence?

It has been proposed that the main role of the ART component of ACTs is to rapidly reduce the infecting parasite biomass by as much as 104-fold every 48 h, while the partner drugs clear the residual, ART-affected parasites (White, 1999). However, there is no direct evidence for the exact mechanism by which companion drugs reduce recrudescence. The companion drugs, which are usually long-acting, could kill dormant parasites directly or kill parasites after they recover from dormancy, or both. To better understand the mechanism Teuscher et al. treated parasites that had been exposed to DHA for 6 h with mefloquine for 24 h in vitro. Mefloquine was washed off after 24 h to ensure that parasites recovering from dormancy were not exposed to the drug. Magnetic columns were used daily after DHA treatment to remove any parasites unaffected by DHA in both the DHA alone and DHA plus mefloquine groups. The authors observed a 10-fold reduction in parasite recovery rate and a delay in recovery compared to DHA treatment alone (Teuscher et al., 2010). This demonstrated that mefloquine had a direct effect on dormant parasites. Since mefloquine has a long half life of ∼2 weeks mefloquine could also kill any parasites recovering from dormancy in vivo, thus having a greater overall effect on parasite recrudescence than that observed with only one 24 h treatment in vitro.

2.4. In vivo evidence

In contrast to in vitro data there have been no reports to date that dormant parasites exist in humans following treatment with ART. This may simply be due to investigators not recognising these abnormal looking parasites in patients’ blood smears after treatment. It may also be that human organs such as the spleen remove severely damaged and dead parasite infected red cells, and only leave the very small proportion of dormant parasites circulating at densities below the detection threshold for microscopy.

To investigate whether dormancy occurs in vivo, LaCrue et al. developed a synchronous rodent malaria model using P. vinckei petteri (non-lethal) and P. v. vinckei (lethal) in which the development of blood stage parasites is relatively synchronous and parasitemias can routinely reach 40% (LaCrue et al., 2011). Infected mice were treated with AS at different stages of parasite development. The results showed that in both the non-lethal and lethal strains, ring-stage parasites were the least susceptible to treatment, and that 24 h post-treatment dormant parasites similar in morphology to those seen with P. falciparum in vitro were observed. A transfer experiment was also conducted in which dormant forms from the treated donor mouse were transferred in varying numbers to different groups of recipient mice. This transfer experiment identified a positive correlation between the counted number of dormant parasites transferred and time to reach 5% parasitemia in both intact and asplenic recipient mice (LaCrue et al., 2011). The recovery rate was estimated to be in the order of 1 in 400 dormant parasites which is comparable to that found in vitro. Results also showed that dormant parasites required less time to recover when injected into splenectomised mice compared to spleen intact mice and that overall survival of asplenic mice was lower than in the spleen intact group. These data demonstrated a clear role of the spleen in clearance of parasites following treatment, as well as the possible evasion of spleen pitting of the dormant rings.

2.5. A plausible mechanism for recrudescence

Collectively, these data suggest that dormancy occurs in vitro and in vivo and is a plausible mechanism for the observed high rate of recrudescence following ART monotherapy. This parasite phenotype means it is imperative that ART is only used in combination with other antimalarials. Evidence of dormant rings in other animal models and in patients treated with ART plus evidence of a relationship between dormant rings and recrudescence will consolidate this mechanism. A better understanding of how and what proportion of dormant parasites survive in vivo in view of ex vivo evidence that ring stage parasites (Angus et al., 1997) and ART-affected parasites are retained or pitted by spleen (Buffet et al., 2006) would also help confirm the relationship of dormancy and clinical recrudescence.

2.6. Why don’t all patients recrudesce?

Based on the published recovery rates, a patient carrying 1 × 1010 ring-stage parasites (∼2000 parasites/μL) would have 4 × 105 parasites that recover following ART treatment. Even if this rate is reduced by a further 10- or 100-fold by repeated treatment all patients still have sufficient number of recovered parasites to recrudesce following ART monotherapy. Why then have we not seen all patients recrudesce?

One possibility is that different parasite isolates have widely varying recovery rates from dormancy (Teuscher et al., 2012). Since treatment failure rates are highly sensitive to the dormancy recovery rates (Hoshen et al., 2000; Codd et al., 2011) a population of parasites with a range of dormancy recovery rates could produce variable treatment outcome.

Alternatively, host immunity may play a role. Codd et al. conducted a theoretical study combining the in vitro characteristics of dormant parasites with a P. falciparum infection model (Codd et al., 2011). The authors were able to demonstrate that estimates of parasitological and clinical treatment failure rates matched those measured in field trials when the host antibody response to P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1), a family of proteins produced by the antigenically variable var gene, was included (Codd et al., 2011). In the absence of such an immune response all patients were predicted to fail treatment with ART alone.

2.7. Is dormancy unique to the ART class of compounds?

An important question is whether the dormancy phenomenon is unique to the ART class of compounds or whether it applies to other antimalarial drugs. To date there have been no reports which systematically test different drugs for their effect on inducing dormant parasites. Reports exist on parasite recovery in vitro following treatment with pyrimethamine, sorbitol and mefloquine (Nakazawa et al., 1995, 2002). Based on similar recovery intervals observed after different treatments and no change in parasite susceptibility to drugs after recovery, the authors concluded that there existed a small proportion of parasites (estimated to be 100 in 107 parasites) capable of surviving the treatment and that these parasites were not drug resistant. However a fundamental difference between these results and those using ART is that the recovery intervals were independent of treatment dose, but correlated with the initial parasite number and length of treatment. This may suggest a different mechanism to ART-induced dormancy.

2.8. Is dormancy an innate protection mechanism for all parasites?

Teuscher et al. tested five P. falciparum strains with different genetic backgrounds and observed that all strains were capable of becoming dormant following exposure to DHA, although the rate of recovery differed between strains (Teuscher et al., 2010). This suggests that ART-induced dormancy is a conserved trait in P. falciparum parasites. We hypothesize that dormancy is an innate protection mechanism that parasites use to survive certain types of stress. It may not be specific to ART, rather specific to drugs which act very early in the erythrocytic cycle, against a particular target, or drugs causing a specific type of stress.

3. Summary

We suggest that ART-induced dormancy is likely an innate parasite response to stress where parasite development is temporarily halted for up to 20 days. After the drug concentration decreases, a small proportion of dormant parasites recover and resume growth causing recrudescence or treatment failures. The high efficacy of ACTs is achieved by the companion drug having a direct impact on the dormant parasites, and in the case of long-acting companion drugs, by direct suppression of growth of recovering parasites.

4. Artemisinin resistance

Box 2. Definition of ART resistance (WHO, 2010a).

Only patients who meet the following criteria are classified as having an artemisinin-resistant infection:

-

·

persistence of parasites 7 days after treatment or recrudescence within 28 days after the start of treatment,

-

·

adequate plasma concentration of dihydroartemisinin,

-

·

prolonged time to parasite clearance and

-

·

reduced in vitro susceptibility to dihydroartemisinin.

Current working definition of ART resistance (WHO, 2010a)

-

·

an increase in parasite clearance time, as evidenced by 10% of cases with parasites detectable on day 3 after treatment with an ACT (suspected resistance); or

-

·

treatment failure after treatment with an oral artemisinin-based monotherapy with adequate antimalarial blood concentration, as evidenced by the persistence of parasites for 7 days, or the presence of parasites at day 3 and recrudescence within 28/42 days (confirmed resistance).

The emergence of ART resistance has always been a serious concern since the worldwide introduction of ACTs in 2001. It is considered almost inevitable that resistance will develop as history shows parasites have developed resistance to all other widely used antimalarial drugs. It has long been proposed that combination therapy should delay the development of resistance (Peters, 1990; White, 1998a) and this principle has been applied to ACTs. However, reports of parasites in Cambodia with decreased in vivo sensitivity to ART (Noedl et al., 2008; Dondorp et al., 2009) have confirmed the emergence of resistance in the field although the clinical efficacy of ACT has not been compromised at this stage. It is uncertain how much unauthorized use of suboptimal ART monotherapy may have contributed to this situation.

4.1. Field observations

ART treatment has been extensively used in China for more than 20 years and until now there has been no documentation of ART resistance in that country. In 2003 Yang et al. reported a three-fold reduction in the in vitro susceptibility of P. falciparum to AS between 1988 and 1999 in Yunnan, Southwest China (Yang et al., 2003).

The first clear, well documented evidence of ART resistance was provided by the results of two separate efficacy trials conducted in Western Cambodia (Noedl et al., 2008; Dondorp et al., 2009). The first trial was conducted in Battambang Province using AS monotherapy; four out of 60 patients recrudesced and two patients had prolonged parasite-clearance times. Parasite isolates from these two patients had a four-fold increase in ex vivo IC50 values compared to those of cured patients, and a 10-fold increase compared to a reference clone (Noedl et al., 2008). The second trial was conducted in Cambodia and Thailand using AS monotherapy and AS plus mefloquine (Dondorp et al., 2009). The results revealed a significant delay in parasite clearance time in Cambodian patients, suggesting the Cambodian P. falciparum isolates had reduced susceptibility to AS. However, few other phenotypic changes were identified. Unlike the first trial the Thai and Cambodian isolates collected in this trial showed no significant differences in their susceptibility (IC50 values) to either DHA or AS when measured using conventional in vitro drug susceptibility tests (Dondorp et al., 2009). No correlation between the delayed parasite clearance and tested putative molecular markers such as pfmdr1, pfATPase6, pfcrt, the 6 kb mitochondrial genome and pfubp-1 were found. Although the resistance was identified to be heritable (Anderson et al., 2010), the molecular mechanism of resistance is currently unknown. Results from Genome-wide studies on these isolates are beginning to be published (Mok et al., 2011), and may help identify changes associated with the delayed clearance phenotype.

Reduced susceptibility of ring-stage parasites to ART has been proposed as an explanation for the prolonged clearance times observed in Cambodia (Dondorp et al., 2009; Saralamba et al., 2010). Mathematical modelling of this hypothesis reproduced the observed parasite clearance for each patient in the trial (Saralamba et al., 2010). This hypothesis also explains why conventional in vitro susceptibility tests that assess the drug effect on the maturation of parasites from ring to schizont stage (Dondorp et al., 2009) did not detect any difference in IC50 value between parasites with normal and prolonged clearance time; the change in susceptibility caused by ring stage resistance alone would be expected to be smaller than that caused by resistance of all stages, and the conventional in vitro susceptibility assay is not sensitive enough to measure the small difference.

ART-induced dormancy also has been proposed as the reason conventional drug susceptibility assays do not detect ART resistance in vitro (Tucker et al., 2012). In conventional assays the parasites are exposed to drug for 24–48 h prior to the addition of a growth indicator (e.g., 3H-hypoxanthine); this time is more than adequate for the ring stage parasites to enter the dormant state. Therefore Tucker et al. hypothesized that by adding 3H-hypoxanthine at time zero (i.e., the same time as drug) any differences in growth of resistant rings would be observed (Tucker et al., 2012). Data with in vitro derived ART-resistant lines of P. falciparum in the modified assay confirmed reduced susceptibility of ART-resistant W2 and D6 lines to artelinic acid (AL), ART, and DHA (Tucker et al., 2012) .

Two urgent tasks face the malaria community: (1) contain the ART-resistant parasites at the foci because their spread could lead to a widespread loss of ACT efficacy and a resurgence of malaria morbidity and death; (2) monitor the emergence of ART resistance in other areas. In order to achieve these important public health goals we need to identify phenotype and genotype changes associated with these resistant parasites and understand the biological and molecular mechanisms of resistance.

4.2. ART resistance in the laboratory

Laboratory selected resistant parasites can provide critical insight about phenotypic and genotypic changes associated with resistance. For this purpose, several laboratories have developed ART-tolerance/resistance in culture adapted parasite lines (Inselburg, 1985; Jiang, 1992; Yang et al., 1999; Chavchich et al., 2010; Witkowski et al., 2010; Beez et al., 2011; Tucker et al., 2012) and in animal models (Chawira et al., 1986; Afonso et al., 2006; Hunt et al., 2007). These lines have been used to investigate the biology and mechanisms of resistance, however many of the earlier resistant lines have proved to be unstable (Jiang, 1992) or only achieved relatively low levels of resistance as measured by in vitro susceptibility tests (Jiang, 1992; Yang et al., 1999), while others are no longer available for study (Inselburg, 1985).

A recent study reported the selection of an ART tolerant-P. falciparum line that can tolerate concentrations 7000-fold higher than the initial IC50 for 48–96 h and recover after the drug pressure was withdrawn (Witkowski et al., 2010). Interestingly only ring stage parasites were observed in cultures that were under drug pressure, and there was no indication that the parasites could grow under continuous drug pressure. The major phenotypic change in the adapted line was an early recovery from dormancy compared to the parental line (Witkowski et al., 2010). No changes in in vitro IC50 value were detected in this line and no association with candidate drug resistant markers was identified (Witkowski et al., 2010). Transcriptome analysis only detected significant changes in the expression of six genes which all encode for exported protein families with the majority involved in antigenic variation. Since the adapted line can tolerate short term high drug concentrations and recover rapidly, we suggest that this line has only changed its dormancy profile, rather than developing full resistance whereby parasites can mature and multiply under drug pressure.

Chavchich et al. also selected in vitro parasite lines that are resistant to an ART derivative, AL from three different parental lines (Chavchich et al., 2010). The IC50 values for these lines showed modest increases of 2–5-fold after the initial selection and up to 12-fold after renewed drug selection (Chen et al., 2010). In contrast to the drug tolerant line reported by Witkowski et al. (2010), these lines were able to grow for at least 20 days under continued AL drug pressure at concentrations to which they had become adapted, that is 17-fold above the IC50 value of parental parasites. The observed changes in IC50 values were accompanied by increases in copy number, mRNA expression, and protein expression of the pfmdr1 gene for 2 of the 3 resistant lines (Chavchich et al., 2010). The IC50 values were partially reversed when de-amplification of the pfmdr1-containing amplicon occurred after culture in the absence of drug-pressure for 3 months (Chen et al., 2010).

A more recent study reported heterogeneity among parents and progeny of the HB3 × Dd2 cross in their in vitro susceptibility to ART (Beez et al., 2011). Polymorphisms in the pfmdr1 gene, plus loci on chromosomes 12 and 13 were identified as contributing to ART susceptibility. Further selection of a stable ART-resistant P. falciparum from a F1 progeny of a genetic cross resulted in a moderate 2- to 4- fold increase in IC50 level. However no additional genetic changes were identified.

4.3. Phenotypes of ART-resistant laboratory lines

Recent laboratory studies (Teuscher et al., 2012) investigated the phenotype of the AL resistant lines reported earlier (Chavchich et al., 2010). Similarly these lines were exposed to higher levels of AL drug pressure as well as to ART and DHA that induced cross-resistance to ART derivatives (Tucker et al., 2012). Through detailed examination of the dormancy profile and growth characteristics of the resistant lines authors of these studies identified three changes in these parasites:

-

1)

Decreased sensitivity in the ring stage to the induction of dormancy. A significantly reduced percentage of ring-stage parasites became dormant following a single exposure to AL, compared to the parental line. For instance, exposing parental lines to 20 ng/mL AL for 6 h was sufficient to cause over 90% dormant rings, while for resistant parasite lines, only concentrations of 640 ng/mL AL, which is at least 8-fold higher than concentrations to which they were adapted, resulted in ∼80% dormant rings (Teuscher et al., 2012). This phenotype supports a hypothesis that dormancy is a response to stress that is triggered when parasites cannot tolerate drug pressure. It is a reflection of parasite resistance to AL.

-

2)

Decreased sensitivity in mature stage parasites. Healthy mature stage parasites were seen in cultures >24 h of drug pressure, suggesting that some parasites can grow and multiply under drug concentrations which kill the parental parasites.

-

3)

When dormancy is induced (using a higher drug concentration) the resistant parasites recover faster leading to earlier recrudescence.

These 3 phenotypic changes provide a profile for ART resistance that has not previously been reported in laboratories or in the field.

4.4. A hypothesis for the development of ART resistance

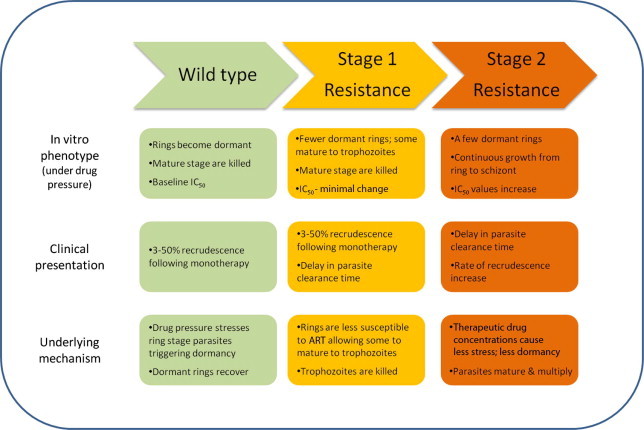

Combining clinical observations from the field with in vitro, animal and theoretical studies, we hypothesise that resistance to ART develops as a two-step process which is linked to the dormancy phenomenon. These stages are described below and illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the developmental steps of ART resistance.

In the absence of resistance the wild type parasites are susceptible to ART derivatives. When exposed to ART, sensitive parasites activate a stress response which results in close to 100% ring stage parasites becoming dormant. Conversely, mature stage parasites are killed by the drug. A very small proportion of dormant parasites recover at a rate dictated by the level of stress, that is, the concentration of drug. In the case of ART monotherapy, dormant parasites recover to cause treatment failure in some patients, dependent on the host immune response. When ART is used as part of ACT, the companion drug may have a direct effect by reducing the number of dormant parasites which recover, as well as killing parasites after they recover. This is the situation which applies to the majority of malaria endemic areas.

The first step toward the development of ART resistance involves changes in the dormancy profile. After repeated exposure to ART some ring stage parasites adapt such that ART exposure induces a lower level of stress, causing a significantly smaller proportion of ring-stage parasites to become dormant. These tolerant ring stages can mature to trophozoites under drug pressure, but perhaps at a reduced speed. This slower parasite maturation results in parasites remaining in the circulation for 48–72 h causing a lengthening of parasite clearance times and a shift of the clearance curve. As the parasites reach mature stage they are killed by the drug as these stages are still sensitive to ART. Conventional in vitro susceptibility testing will not detect significant changes in parasite IC50 values during this stage since mature stage parasites are equally sensitive to ART. The Cambodian field isolates (Dondorp et al., 2009) and the resistant line adapted by Witkowski et al (Witkowski et al., 2010) would fit into this stage of resistance development.

As resistance further develops to the second stage, not only ring stage but also mature stage parasites become less susceptible to ART. At this stage drug pressure at therapeutic levels is no longer sufficient to trigger the stress response of dormancy in the majority of ring stage parasites and mature parasites are able to grow and multiply under drug pressure. These parasites will cause treatment failures following ART monotherapy and ACT, depending on the efficacy of the companion drug. These parasites will show an increase in IC50 value when measured by conventional in vitro susceptibility test. When higher drug doses are used, the stress response can again be triggered and the parasites will use the dormancy mechanism to survive the high drug pressure. Fortunately this situation has not been seen in the field but the AL resistant parasites developed in vitro (Teuscher et al., 2012) fit this stage of resistance.

The molecular changes which are responsible for stage 1 and 2 resistance are not known. Indeed the pathways associated with dormancy itself are still to be elucidated. It is possible that the same molecular changes are responsible for both stages of resistance, although more likely that a different mechanism exists for ART tolerance in ring stage parasites and survival of mature stages. We hypothesise that at stage 1, ring stage parasites may develop a level of tolerance to ART by altering drug targets or transporters. This tolerance reduces the level of stress experienced by parasites during ART exposure, which is reflected by changes in dormancy profile, namely fewer parasites becoming dormant. One possible mechanism to achieve this may be through cell cycle regulation mechanisms. Resistance of mature parasites, as seen in the stage 2, may involve significant or more alterations (mutations) of drug targets or alterations in transporters. Laboratory evidence suggests that amplification of pfmdr1 (Chavchich et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2012) may be associated with survival of mature stage parasites, although it is unlikely to be solely responsible. Other candidate genes such as pfATPase 6 (Uhlemann et al., 2005), pftctp (Bhisutthibhan et al., 1998) and pfubp-1(Hunt et al., 2007) may also be involved even though they are not implicated in field isolates at this early stage of resistance development.

Currently, the best marker for ART resistance is the reduced parasite clearance rate observed as part of therapeutic efficacy trials. These trials are expensive and time consuming; an in vitro test would greatly improve resistance monitoring. Tolerability of ring stage parasites to ART could be used as a marker for a new in vitro susceptibility test where the output is not the percentage of parasites that reach schizonts, rather the percentage of rings that survive to trophozoites, or the percentage of rings becoming dormant following drug exposure. If the ART resistance is stopped at stage 1, we may not detect significant IC50 changes in field isolates.

A better understanding of the processes underlying the development of resistance, and mechanisms of resistance, will greatly assist the effort to monitor, contain and eliminate ART resistant parasites, and most importantly to prevent detrimental public health consequences that may be caused by the spread of ART resistance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by funding to the authors by the US NIAID (R01 AI058973). M.L. Gatton is supported by NHMRC CDA and the Research and Policy for Infectious Disease Dynamics (RAPIDD) program of the Science and Technology Directorate, Department of Homeland Security, and the Fogarty International Centre, National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Drs Dennis Shanks and Bob Cooper for proofreading the manuscript and providing suggestions.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Defence Force Joint Health Services.

References

- Afonso A., Hunt P., Cheesman S., Alves A.C., Cunha C.V., do R.V., Cravo P. Malaria parasites can develop stable resistance to artemisinin but lack mutations in candidate genes atp6 (encoding the sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase), tctp, mdr1, and cg10. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006;50:480–489. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.2.480-489.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson T.J., Nair S., Nkhoma S., Williams J.T., Imwong M., Yi P., Socheat D., Das D., Chotivanich K., Day N.P., White N.J., Dondorp A.M. High heritability of malaria parasite clearance rate indicates a genetic basis for artemisinin resistance in western Cambodia. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1326–1330. doi: 10.1086/651562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angus B.J., Chotivanich K., Udomsangpetch R., White N.J. In vivo removal of malaria parasites from red blood cells without their destruction in acute falciparum malaria. Blood. 1997;90:2037–2040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint G.A. Artemisinin and its derivatives: an important new class of antimalarial agents. Pharmacol. Ther. 2001;90:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beez D., Sanchez C.P., Stein W.D., Lanzer M. Genetic predisposition favors the acquisition of stable artemisinin resistance in malaria parasites. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:50–55. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00916-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhisutthibhan J., Pan X.Q., Hossler P.A., Walker D.J., Yowell C.A., Carlton J., Dame J.B., Meshnick S.R. The Plasmodium falciparum translationally controlled tumor protein homolog and its reaction with the antimalarial drug artemisinin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16192–16198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.26.16192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman A. Malaria associated anaemia, drug resistance and antimalarial combination therapy. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:1637–1643. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray P.G., Ward S.A., O’Neill P.M. Quinolines and artemisinin: chemistry, biology and history. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2005;295:3–38. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29088-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffet P.A., Milon G., Brousse V., Correas J.M., Dousset B., Couvelard A., Kianmanesh R., Farges O., Sauvanet A., Paye F., Ungeheuer M.N., Ottone C., Khun H., Fiette L., Guigon G., Huerre M., Mercereau-Puijalon O., David P.H. Ex vivo perfusion of human spleens maintains clearing and processing functions. Blood. 2006;107:3745–3752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bwijo B., Hassan A.M., Abbas N., Eriksson O., Bjorkman A. Repetitive dosing of artemisinin and quinine against Plasmodium falciparumin vitro: a simulation of the in vivo pharmacokinetics. Acta Trop. 1997;65:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(96)00565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavchich M., Gerena L., Peters J., Chen N., Cheng Q., Kyle D.E. Role of pfmdr1 amplification and expression in induction of resistance to artemisinin derivatives in Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2455–2464. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00947-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawira, A.N., Warhurst, D.C., Peters, W., 1986. Qinghaosu resistance in rodent malaria. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 80, 477–480. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen N., Chavchich M., Peters J.M., Kyle D.E., Gatton M.L., Cheng Q. Deamplification of pfmdr1-containing amplicon on chromosome 5 in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with reduced resistance to artelinic acid in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3395–3401. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01421-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codd A., Teuscher F., Kyle D.E., Cheng Q., Gatton M.L. Artemisinin-induced parasite dormancy: a plausible mechanism for treatment failure. Malar. J. 2011;10:56. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumming J.N., Ploypradith P., Posner G.H. Antimalarial activity of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and related trioxanes: mechanism(s) of action. Adv. Pharmacol. 1997;37:253–297. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60952-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries P.J., Dien T.K. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutic potential of artemisinin and its derivatives in the treatment of malaria. Drugs. 1996;52:818–836. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X.C., Beck H.P., Raso G. Plasmodium sensitivity to artemisinins: magic bullets hit elusive targets. Trends Parasitol. 2010;27(2):73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dondorp A.M., Nosten F., Yi P., Das D., Phyo A.P., Tarning J., Lwin K.M., Ariey F., Hanpithakpong W., Lee S.J., Ringwald P., Silamut K., Imwong M., Chotivanich K., Lim P., Herdman T., An S.S., Yeung S., Singhasivanon P., Day N.P., Lindegardh N., Socheat D., White N.J. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:455–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta G.P., Bajpai R., Vishwakarma R.A. Artemisinin (qinghaosu)–a new gametocytocidal drug for malaria. Chemotherapy. 1989;35:200–207. doi: 10.1159/000238671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gera R., Khalil A. Artemisinine and its derivatives. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:813–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giao P.T., Binh T.Q., Kager P.A., Long H.P., Van Thang N., Van Nam N., de Vries P.J. Artemisinin for treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria: is there a place for monotherapy? Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2001;65:690–695. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R.K., Krishna S. Artemisinins: activities and actions. Microb. Infect. 2004;6:1339–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshen M.B., Na-Bangchang K., Stein W.D., Ginsburg H. Mathematical modelling of the chemotherapy of Plasmodium falciparum malaria with artesunate: postulation of ‘dormancy’, a partial cytostatic effect of the drug, and its implications for treatment regimes. Parasitology. 2000;121:237–246. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099006332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt P., Afonso A., Creasey A., Culleton R., Sidhu A.B., Logan J., Valderramos S.G., McNae I., Cheesman S., Do R.V., Carter R., Fidock D.A., Cravo P. Gene encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme is mutated in artesunate- and chloroquine-resistant rodent malaria parasites. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:27–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inselburg J. Induction and isolation of artemisinine-resistant mutants of Plasmodium falciparum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985;34:417–418. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ittarat W., Pickard A.L., Rattanasinganchan P., Wilairatana P., Looareesuwan S., Emery K., Low J., Udomsangpetch R., Meshnick S.R. Recrudescence in artesunate-treated patients with falciparum malaria is dependent on parasite burden not on parasite factors. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;68:147–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G.F. In vitro development of sodium artesunate resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Chung. Kuo. Chi. Sheng. Chung. Hsueh. Yu. Chi. Sheng. Chung. Ping. Tsa. Chih. 1992;10:37–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N., Zheng H. Stage-specific gametocytocidal effect in vitro of the antimalaria drug qinghaosu on Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol. Res. 1990;76:214–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00930817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle, D.E., Webster, H.K., 1996. Postantibiotic effect of quinine and dihydroartemisin on Plasmodium falciparum in vitro: implications for a mechanism of recrudescence. In: XIVth International Congress for Tropical Medicine and Malaria, 1996.

- Kyle D.E., Teja I.P., Li Q., Leo K. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of qinghaosu derivatives: how do they impact on the choice of drug and the dosage regimens? Med. Trop. Mars. 1998;58:38–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaCrue A.N., Scheel M., Kennedy K., Kumar N., Kyle D.E. Effects of artesunate on parasite recrudescence and dormancy in the rodent malaria model plasmodium vinckei. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wu Y.L. How Chinese scientists discovered qinghaosu (artemisinin) and developed its derivatives? What are the future perspectives? Med. Trop. Mars. 1998;58:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looareesuwan S., Wilairatana P., Viravan C., Vanijanonta S., Pitisuttithum P., Kyle D.E. Open randomized trial of oral artemether alone and a sequential combination with mefloquine for acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1997;56:613–617. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh H.M., Olliaro P. Artemisinin derivatives for treating uncomplicated malaria. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1999;2:CD000256. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshnick S.R., Taylor T.E., Kamchonwongpaisan S. Artemisinin and the antimalarial endoperoxides: from herbal remedy to targeted chemotherapy. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:301–315. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.301-315.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshnick S.R. Artemisinin antimalarials: mechanisms of action and resistance. Med. Trop. Mars. 1998;58:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshnick S.R. Artemisinin: mechanisms of action, resistance and toxicity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok S., Imwong M., Mackinnon M.J., Sim J., Ramadoss R., Yi P., Mayxay M., Chotivanich K., Liong K.-Y., Russell B., Socheat D., Newton P.N., Day N.P., White N.J., Preiser P.R., Nosten F., Dondorp A.M., Bozdech Z. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with an altered temporal pattern of transcription. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa S., Kanbara H., Aikawa M. Plasmodium falciparum: recrudescence of parasites in culture. Exp. Parasitol. 1995;81:556–563. doi: 10.1006/expr.1995.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa S., Maoka T., Uemura H., Ito Y., Kanbara H. Malaria parasites giving rise to recrudescence in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:958–965. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.958-965.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.S., Dao B.H., Nguyen P.D., Nguyen V.H., Le N.B., Mai V.S., Meshnick S.R. Treatment of malaria in Vietnam with oral artemisinin. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993;48:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noedl H., Se Y., Schaecher K., Smith B.L., Socheat D., Fukuda M.M. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosten F., White N.J. Artemisinin-based combination treatment of falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2007;77:181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenholt I., Lowdin E., Cars O. Studies of the killing kinetics of benzylpenicillin, cefuroxime, azithromycin, and sparfloxacin on bacteria in the postantibiotic phase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2522–2526. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olliaro P.L., Taylor W.R. Developing artemisinin based drug combinations for the treatment of drug resistant falciparum malaria: a review. J. Postgrad. Med. 2004;50:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters W. The prevention of antimalarial drug resistance. Pharmacol. Ther. 1990;47:499–508. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(90)90067-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., Nosten F., Luxemburger C., Ter-Kuile F.O., Paiphun L., Chongsuphajaisiddhi T., White N.J. Effects of artemisinin derivatives on malaria transmissibility. Lancet. 1996;347:1654–1658. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price R.N., Nosten F. Drug resistant falciparum malaria: clinical consequences and strategies for prevention. Drug Resist. Updat. 2001;4:187–196. doi: 10.1054/drup.2001.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saralamba S., Pan-Ngum W., Maude R.J., Lee S.J., Tarning J., Lindegardh N., Chotivanich K., Nosten F., Day N.P., Socheat D., White N.J., Dondorp A.M., White L.J. Intrahost modeling of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;108:397–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targett G., Drakeley C., Jawara M., von Seidlein L., Coleman R., Deen J., Pinder M., Doherty T., Sutherland C., Walraven G., Milligan P. Artesunate reduces but does not prevent posttreatment transmission of Plasmodium falciparum to Anopheles gambiae. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;183:1254–1259. doi: 10.1086/319689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher F., Gatton M.L., Chen N., Peters J., Kyle D.E., Cheng Q. Artemisinin-induced dormancy in Plasmodium falciparum: duration, recovery rates, and implications in treatment failure. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202:1362–1368. doi: 10.1086/656476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher F., Chen N., Kyle D.E., Gatton M.L., Cheng Q. Phenotypic changes in artemisinin resistant Plasmodium falciparum lines in vitro: evidence for decreased sensitivity to dormancy and growth inhibition. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:428–431. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05456-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjitra E., Anstey N.M., Sugiarto P., Warikar N., Kenangalem E., Karyana M., Lampah D.A., Price R.N. Multidrug-resistant plasmodium vivax associated with severe and fatal malaria: a prospective study in Papua, Indonesia. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e128. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trape J.F., Pison G., Preziosi M.P., Enel C., Desgrees-du L.A., Delaunay V., Samb B., Lagarde E., Molez J.F., Simondon F. Impact of chloroquine resistance on malaria mortality. C. R Acad Sci III. 1998;321:689–697. doi: 10.1016/s0764-4469(98)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker M.S., Mutka T., Sparks K., Patel J., Kyle D.E. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of in vitro selected artemisinin-resistant progeny of Plasmodium falciparum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:302–314. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlemann A.C., Cameron A., Eckstein-Ludwig U., Fischbarg J., Iserovich P., Zuniga F.A., East M., Lee A., Brady L., Haynes R.K., Krishna S. A single amino acid residue can determine the sensitivity of SERCAs to artemisinins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:628–629. doi: 10.1038/nsmb947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warsame M., Wernsdorfer W.H., Ericsson O., Bjorkman A. Isolated malaria outbreak in Somalia: role of chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum demonstrated in Balcad epidemic. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1990;93:284–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J. Assessment of the pharmacodynamic properties of antimalarial drugs in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1413–1422. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J. Preventing antimalarial drug resistance through combinations. Drug Resist. Updat. 1998;1:3–9. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(98)80208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J. Qinghaosu in combinations. Med. Trop. Mars. 1998;58:85–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White N.J. Delaying antimalarial drug resistance with combination chemotherapy. Parassitologia. 1999;41:301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2010a. Global report on antimalarial drug efficacy and drug resistance 2000–2010.

- WHO, 2010b. World malaria report 2010.

- Witkowski B., Lelievre J., Barragan M.J., Laurent V., Su X.Z., Berry A., Benoit-Vical F. Increased tolerance to artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum is mediated by a quiescence mechanism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1872–1877. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01636-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Gao B., Huang K. Comparison of sensitivity of artesunate-sensitive and artesunate-resistant Plasmodium falciparum to chloroquine and amodiaquine. Zhongguo Ji. Sheng Chong. Xue. Yu Ji Sheng Chong. Bing. Za Zhi. 1999;17:353–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Liu D., Yang Y., Fan B., Yang P., Li X., Li C., Dong Y., Yang C. Changes in susceptibility of Plasmodium falciparum to artesunate in vitro in Yunnan Province, China. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003;97:226–228. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(03)90127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker J.R., Lackritz E.M., Ruebush T.K., Hightower A.W., Adungosi J.E., Were J.B., Metchock B., Patrick E., Campbell C.C. Childhood mortality during and after hospitalization in western Kenya: effect of malaria treatment regimens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1996;55:655–660. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]