Abstract

Background and Aims

Current methods to diagnose malignant biliary strictures are of low sensitivity. Confocal endomicroscopy is a new approach that may improve the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures. The purpose of this study was to evaluate indeterminate biliary strictures using probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy and to understand the histologic basis for the confocal images.

Methods

Fourteen patients with indeterminate biliary strictures underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with examination of their common bile duct with fluorescein-aided probe-based confocal laser endomicroscopy. Standard brushings and biopsies were performed. In parallel, rat bile ducts were examined either with conventional staining and light microscopy or with multiphoton microscopy.

Results

Earlier published criteria were used to evaluate possible malignancy in the confocal images obtained in the 14 patients. None of the individual criteria were found to be specific enough for malignancy, but a normal-appearing reticular pattern without other putative markers of malignancy was observed in all normal patients. Multiphoton reconstructions of intact rat bile ducts revealed that the reticular pattern seen in normal tissue was in the same focal plane but was smaller than blood vessels. Special stains identified the smaller structures in this network as lymphatics.

Conclusions

Our limited series suggests that a negative confocal imaging study of the biliary tree can be used to rule out carcinoma, but there are frequent false positives using individual earlier published criteria. An abnormal reticular network, which may reflect changes in lymphatics, was never seen in benign strictures. Better correlation with known histologic structures may lead to improved accuracy of diagnoses.

Keywords: confocal endomicroscopy, gastrointestinal malignancies, cholangiocarcinoma, biliary strictures

Differentiation between benign and malignant biliary strictures is difficult even with advanced endoscopic imaging or cytologic techniques.1-4 Cholangiocarcinomas are particularly difficult to diagnose in part because, unlike other tumors, most cholangiocarcinomas grow along the bile duct wall rather than radially to form a mass.1,3 Other malignancies involving the bile ducts include pancreatic and gallbladder cancer, as well as other metastatic diseases. Benign etiologies include inflammation, pancreatitis, ischemia, and iatrogenic and idiopathic causes.5 Methods to diagnose malignant biliary strictures include endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with tissue sampling, fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) to detect chromosomal abnormalities, or digital image analysis (DIA) to measure the intensity of dye-stained nuclei to quantify cellular DNA.2,6 A definitive diagnosis often cannot be made because of the low sensitivity of these diagnostic methods.2,6,7 The delay in tissue confirmation of malignancy can place a patient at risk for progression of disease precluding surgical resection. The patient could also undergo unnecessary surgery due to the inability to confirm whether a stricture is benign or malignant.5

Confocal endomicroscopy is a relatively new imaging technique that has been used for in-vivo diagnosis of dysplasia and malignancies along the gastrointestinal tract, or else to obtain directed biopsies that will allow diagnoses of gastrointestinal malignancies with greater accuracy.8-13 The technique requires injection of fluorescein or another fluorophore, followed by endoscopic imaging of the dye to identify mucosal details such as crypt and vessel architecture to distinguish among normal, dysplastic, and neoplastic tissue.10 For biliary imaging, a confocal miniprobe is passed through the channel of a side-viewing endoscope and advanced into the biliary tree through a hinged catheter or cholangioscope. A single published study using probebased confocal laser endomicroscopy (pCLE) in patients suggested that it can improve diagnostic accuracy of indeterminate biliary strictures and proposed a set of diagnostic criteria for this purpose.14 The goal of this study was to apply these diagnostic criteria prospectively in patients with biliary strictures undergoing pCLE, and to understand the histologic basis for the image patterns that are observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Fourteen consecutive patients referred to the Gastrointestinal Procedure Center at our institution for ERCP to rule out biliary malignancy were recruited to participate in this study, which was approved by the Yale University Human Investigations Committee. Written informed consent was obtained before study participation. Inclusion criteria included age above 18 years and the ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included having a known allergy or a prior adverse reaction to fluorescent contrast agents or chromoendoscopy stains; below the age of 18 years or mentally or legally incapacitated or otherwise unable to give informed consent; are pregnant or breastfeeding; coagulopathy; and impaired renal function.

Confocal Imaging

A confocal miniprobe (Cellvizio, Mauna Kea Technologies, Paris, France) was used to examine the biliary mucosa in all cases. All 14 patients undergoing ERCP received up to 10 mL of 0.5% to 10% intravenous fluorescein approximately 2 to 3 minutes before imaging. Biliary strictures and bile ducts were imaged using either a CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe in most patients or a GastroFlex ultra-high definition (UHD) high-definition confocal miniprobe. The CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe is compatible with a 1.2 mm operating channel, has a lateral resolution of 3.5 μm, a depth of focus of 40 to 70 μm, and a field of view of 325 μm. The GastroFlex UHD confocal miniprobe was used in 1 patient. It is compatible with a 2.8 mm working channel, has a lateral resolution of 1 μm, a depth of focus of 55 to 65 μm, and field of view of 240 μm. The CholangioFlex miniprobe was inserted into the common bile duct (CBD) through a Spyglass (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) catheter or Olympus swing tip catheter. The GastroFlex UHD miniprobe was inserted into the CBD using a freehand technique. The bile duct was cannulated with a standard ERCP catheter which was removed and a 0.035-inch guide wire left in place. The UHD probe was then inserted adjacent to the guidewire.

Histology

Standard biopsy forceps and brushings were used to obtain cytology and tissue from the biliary tree during ERCP when clinically indicated. Biopsy specimens were collected in 10% buffered formalin (Val Tech Diagnostics, PA), were routinely processed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 3 μm. They were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and examined using standard bright field (white light) microscopy.

Multiphoton Studies of Bile Duct Histology

Fresh, unfixed-rat bile ducts were examined with a multiphoton microscope to correlate confocal images with the corresponding histologic structure. Studies were approved by the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult male Sprague Dawley rats were anesthetized, subject to laparotomy to expose the inferior vena cava and CBD, and then injected with 1% fluorescein (1 mL/kg) in the inferior vena cava. Three minutes later, the CBD was removed and transferred to a dish containing cold saline and cut open lengthwise to expose the luminal surface, then the animal was euthanized. The duct was then placed in an incubation chamber fitted on the stage of a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO confocal/multiphoton microscope (Thornwood, NY). A mode-locked, femtosecond-pulsed Mai Tai laser (Spectra Physics, Mountain View, CA) tuned to 735 nm was used as a light source, and custom-built nondescanned (external) detectors were used to collect emission images at 320 to 380 nm, 410 to 490 nm, and 510 to 650 nm as described earlier.15

Immunohistology of Bile Ducts

In correlative separate studies of rat bile ducts, whole CBDs were collected in 10% buffered formalin, and then processed, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 3 μm intervals. Sections were pretreated with 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer, and then endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% H2O2 in absolute methanol. Each section was preincubated in rabbit serum for 10 minutes, then incubated with lymphatic tissue-specific mouse monoclonal antibody D2-40 (DAKO #M3619; Carpinteria, CA) diluted 1:500 for 60 minutes. Subsequently, sections were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen, and sections were counterstained with H&E and examined using standard bright field (white light) microscopy.

RESULTS

Fourteen patients with biliary strictures were enrolled in the study. Table 1 lists the patients and their diagnosis after ERCP. Patient diagnoses were categorized as either normal, indeterminate, or malignant according to the results of the ERCP and clinical or pathologic findings. Normal diagnoses included Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and pancreatitis-related biliary stricture. Patients categorized as indeterminate included patients with distal CBD stricture with atypia on biopsy, distal CBD stricture in a patient with primary sclerosing cholangitis, and distal CBD stricture in a patient with acute cholecystitis. Patients diagnosed with a malignancy as a cause for their ERCP findings were placed in the malignant category. Of the 14 patients, 6 patients had a diagnosis of cancer. The diagnosis of cancer was known in 2 patients before confocal endomicroscopy. Follow up for patients ranged from 7 months to 1 year.

TABLE 1.

List of Patients and Diagnosis Post-ERCP and Confocal Endomicroscopy

| History | Diagnosis | Biopsies | Confocal Determination |

Confocal Pattern |

Bismuth Classification |

Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acute cholecystitis s/p percutaneous drain; abrupt cut off CBD |

Unknown | Atypia | Indeterminate | 1, 2 | Distal CBD | ERCP october 2009, biopsy negative |

| 2 | Recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis; prior CBD stenting |

Sphincter of Oddi, stricture |

Atypia | Indeterminate | 1, 2 | Distal CBD | No follow-up ERCP |

| 3 | Jaundice | Cholangiocarci- noma |

Adenocar- cinoma |

Malignant | 1, 2 | I | Cancer diagnosis |

| 4 | RUQ pain; MRCP showed IHD |

Normal CBD | No biopsy | Normal | 2 | Dilated IHD, no stricture |

No follow-up ERCP |

| 5 | Distal CBD stricture s/p prior stent |

CBD stricture | Focal atypia | Indeterminate | 1, 2, 3 | Distal CBD | ERCP september 2009, wall-flex stent placed |

| 6 | PSC, CBD stricture; prior ERCP |

PSC | Negative | Indeterminate | 1, 3 | IV | ERCP november 2009, no biopsy |

| 7 | Pancreatic cancer, biliary drain, CBD stent |

Pancreatic cancer |

No biopsy | Malignant | 1, 2, 3 | Distal CBD/I | Cancer diagnosis |

| 8 | Pancreatitis, distal CBD stricture prior stents |

Unknown | Submucosal fibrosis |

Normal | 2 | Distal CBD/I | No follow-up |

| 9 | Abnormal LFTs, dilated CBD |

Papillary stenosis |

No biopsy | Normal | 2 | No stricture, papillary stenosis |

ERCP august 2009 negative |

| 10 | Biliary obstruction; mid-CBD and hilum strictures |

Cholangiocar- cinoma versus breast cancer |

Carcinoma | Malignant | 1, 2, 3 | IV | No follow-up |

| 11 | Distal CBD stricture s/p prior stent |

Cholangiocar- cinoma |

Adenocar- cinoma |

Malignant | 1, 3 | Distal CBD | Cancer diagnosis |

| 12 | Pancreatic cancer; CBD stricture s/p prior CBD stent |

Pancreatic cancer |

No biopsy | Malignant | 1, 2, 3 | Distal CBD | Cancer diagnosis |

| 13 | Hemochromatosis; CHD/hilar stricture on MRCP |

Pancreatic cancer |

Mild atypia | Malignant | Dark spots only |

IIIa | Cancer diagnosis |

| 14 | Distal CBD stricture; indeterminate biopsies |

Unknown | Mild atypia | Indeterminate | 1, 2, 3 | Distal CBD | No follow-up |

Confocal pattern—Irregular epithelial lining = 1, Reticular pattern = 2, Loss of mucosal structure = 3.

CBD indicates common bile duct; CHD, common hepatic duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; IHD, intrahepatic duct; LFTs, liver function tests; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PSC, primary sclerosis cholangitis; RUQ, right upper quadrant; s/p, status post.

Earlier published criteria were used to evaluate possible malignancy in the confocal images obtained in the 14 patients as follows14:

Loss of reticular pattern of epithelial bands of less than 20 μm and detection of irregular epithelial lining, villi, or gland-like structures;

Complete loss of mucosal structures (suggestive for fibrosis);

Tortuous, dilated, and saccular vessels with inconsistent branching;

Presence of “black areas” (decreased uptake of fluorescein).

These criteria differ slightly from the Miami classification, a more detailed but as yet unpublished set of criteria developed by a confocal users group (Appendix). Examples of the above imaging criteria are shown in the following figures. Figure 1 shows a normal reticular pattern observed using the CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe. The reticular bands are less than 20 μm in length and appear in an ordered structure. Figure 2 shows an example of irregular epithelium. The epithelium has lost its normal structure of regular, adjacent cells. Normal mucosal structures are shown in Figure 3 for comparison. The criterion of tortuous, dilated, and saccular vessels with inconsistent branching was not used in this study because these structures were seen in the normal bile duct. This criterion was based on findings using the CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe. Using the high-definition probe in a normal CBD, fluorescein-filled tortuous vessels with streaming red cells were clearly visible (Fig. 4). This argues against the presence of such fluorescein-filled vessels as being diagnostic for the presence of cancer and therefore that criterion was not used in this study. The last criterion, presence of black areas, was not a sufficiently specific descriptor to be able to include or exclude findings during confocal endomicroscopy and therefore that criterion also was not used here.

FIGURE 1.

Reticular pattern (arrows) in a normal bile duct. This pattern was observed by confocal imaging using the Cholangio-Flex confocal miniprobe.

FIGURE 2.

An example of irregular epithelium. The epithelium has lost its normal structure of regular, adjacent cells. This pattern was observed by confocal imaging using the CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe.

FIGURE 3.

Normal bile duct epithelium observed by confocal imaging using the CholangioFlex confocal miniprobe.

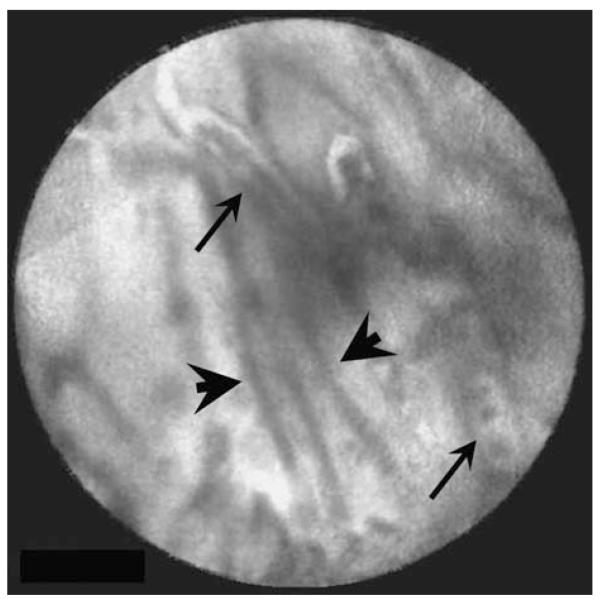

FIGURE 4.

Normal bile duct observed by confocal imaging using the GastroFlex UHD high-definition confocal miniprobe. Note that blood vessels (arrows) can be identified as white (fluorescein-filled) structures that contain red blood cells, which exclude fluorescein. Dark reticular structures (arrowheads) are seen in the same focal plane.

Table 1 summarizes the confocal endomicroscopy results of the 14 patients studied. Three patients were found to have benign conditions after ERCP. These patients had a reticular pattern with dark spots on confocal endomicroscopy. There were 5 patients whose diagnosis was categorized as indeterminate. In 2 of these patients, the reticular pattern was observed that has previously been thought to represent a benign condition. However, irregular epithelium also was observed in these patients. Other patients in the indeterminate category had abnormal findings on endomicroscopy including loss of mucosal structures and a tortuous dilated pattern. Some of those patients diagnosed with cancer had a normal reticular pattern present but also had the loss of mucosal structures and irregular epithelium. One patient with pancreatic cancer had only dark spots present on confocal endomicroscopy. Table 1 also shows follow up for each patient, if known. Although limited by the study size, these findings raise the possibility that, if a normal reticular pattern is seen without markers of potential malignancy, then the diagnosis of malignancy is unlikely.

To improve characterization of human biliary structures, the high-definition confocal miniprobe was used in 1 patient with a normal bile duct. Fluorescein-filled blood vessels with dark blood cells coursing through the vessel could be identified (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Video 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JCG/A21). Dark reticular structures with a diameter smaller than that of the fluorescein-filled vessels were also observed. This supported the conclusion that the dark reticular pattern does not represent blood vessels.

Multiphoton imaging of intact rat bile duct was used to better understand the nature of the human bile duct structures visualized during confocal endomicroscopy and to correlate these structures with standard histologic findings. The optimal multiphoton excitation wavelength for tissue autofluorescence and collagen second harmonic generation has been described earlier.15 Serial cross-sectional images of the rat bile duct using multiphoton imaging were collected (Fig. 5) and 3-dimensional images of the ducts were reconstructed (Supplementary Video 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JCG/A22). Three-dimensional architecture revealed surface epithelium with pits associated with peribiliary mucous glands extending from the pits into the tissue (Figs. 5A, B).16,17 These glands formed ductules lined by cuboidal cells, which were surrounded by stroma that was identified by second harmonic generation (Figs. 5B, C). A network of vascular-appearing structures within the stroma was observed surrounding the ductules at a depth of approximately 50 μm (Fig. 5C), which also is the depth of the focal plane observed by the CholangioFlex probe. To correlate the reticular structures seen using confocal imaging in patients and multiphoton imaging in rats, rat bile duct tissue was stained first with H&E and then with an immunolabel for lymphatics. Figure 6A shows a network of vascular structures located at the base of the ductules. Lymphatic staining reveals that the smallest of these structures are lymphatic ductules (Fig. 6B). Given the size and depth of these lymphatics, this suggests that they constitute the reticular pattern seen by confocal endomicroscopy.

FIGURE 5.

Serial optical sections of rat common bile duct examined by multiphoton microscopy. The duct was examined in a freshly isolated, unfixed, and unstained duct. The image is pseudocolored to reveal emission signals detected at 320 to 380 nm (blue), 410 to 490 nm (green), and 510 to 650 nm (red). A, Surface section reveals confluent epithelia with interspersed pits (green). B, Section collected approximately 25 μm beneath the luminal surface reveals glands (green) that extend from the pits, surrounded by connective tissue (blue). C, Section collected approximately 50 μm beneath the luminal surface reveals termination of the glands (green), surrounded by connective tissue (blue). At this depth a vascular network (red) is now visible within the stroma.

FIGURE 6.

Histologic sections of rat common bile duct. A, Hematoxylin and eosin-stained section along the length of the duct reveals epithelia lining the lumen with occasional pits that extend into glands surrounded by connective tissue. Vascular structures can be seen at the periphery of the connective tissue. Pancreatic acini surround the duct. B, D2-40 immunostaining of lymphatics (arrows) identifies multiple small structures in the periphery of the connective tissue, at nearly the same depth from the luminal surface as blood vessels.

DISCUSSION

Confocal endomicroscopy permits true microscopic examination of structures during the course of an endoscopic examination. Confocal microscopy only visualizes fluorescence, therefore flourescein typically is injected for such studies and then its fluorescence distribution is detected. Certain structures, such as blood vessels and normal mucosal epithelium, concentrate flourescein and can be recognized based on their pattern of fluorescence, whereas other structures, such as erythrocytes or dysplastic cells, can be recognized by their exclusion of fluorescein fluorescence. Here, we examined the microscopic patterns visible within the CBD using pCLE in patients with indeterminate biliary strictures. Our results suggest that a normal reticular pattern without loss of mucosal structures or irregular-appearing epithelium is a good predictor of a benign biliary stricture. The confocal miniprobe has been used earlier for the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma in patients with biliary stenosis.14 Two different endomicroscopic patterns were found to be diagnostically useful in that study. Images in patients with cancer were characterized by loss of identifiable mucosal structures, as well as the presence of white bands thought to be fluorescein-filled tortuous, dilated, and saccular vessels with inconsistent branching.14 Noncancerous tissue instead was characterized by a reticular pattern or else small dark-grey villous structures without white bands. That study reported a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 88% for the diagnosis of neoplasia.14 Our study was not able to replicate the usefulness of these imaging patterns for the diagnosis of neoplasia. In contrast, here we found the presence of a reticular pattern without concomitant imaging patterns seen in cholangiocarcinoma to be specific for non-neoplastic tissue.

Pancreaticobiliary strictures are difficult to diagnose accurately because of limitations of current diagnostic methods and characteristics of cholangiocarcinomas.2,6,7 Ninety-five percent of cholangiocarcinomas are adenocarcinomas and are classified as either mass-forming, periductal-infiltrating, or intraductal-growing cholangiocarcinomas.3,4 Mass-forming cholangiocarcinomas are firm tumors because of desmoplastic reaction, and typically form a nodule arising from the mucosa which grows into the lumen causing biliary obstruction.18 Periductal-infiltrating cholangiocarcinomas grow along the bile duct wall, causing concentric thickening of the wall. The tumor may cause a fibroblastic reaction involving vessels. This type of tumor represents most of the hilar cholangiocarcinomas, whereas most peripheral cholangiocarcinomas are massforming type.18 Intraductal-growing papillary cholangiocarcinomas form papillary tumors within the lumen causing obstruction in a cast-like formation or at times a mass. This tumor produces mucin which may cause obstruction.1,18 Benign conditions causing pancreaticobiliary strictures, such as ischemia after gallbladder resection or inflammation associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis are often indistinguishable radiologically from strictures due to cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, or metastatic disease using imaging modalities such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, or endoscopic ultrasound.5 Current methods for cytopathologic diagnosis, which include brushings, biopsies, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA), provide only incremental diagnostic benefit.2,6,7,19,20 In 1 series, the correct diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma was made in only 23% of cases using brush cytology, and this increased to only 47% when brush cytology, biopsy, and FNA were combined when all atypia were excluded.21 In 1 review of methods for the diagnosis of biliary strictures, sensitivity of brush cytology ranged from 30% to 57%, sensitivity of forceps biopsy ranged from 43% to 81%, and FNA sensitivity ranged from 26% to 62%.19,20 The low sensitivity of brushing, biopsy, and FNA has provided the motivation to use more advanced molecular and cellular imaging techniques to diagnose malignant strictures. FISH uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to detect chromosomal abnormalities in tissue. DIA is a technique which uses a Feulgen dye that stoichiometrically binds to DNA. The DNA is then quantified to determine the ploidy of the cell. In a study of pancreatobiliary strictures, FISH had a sensitivity of 35% to 60%, whereas DIA sensitivity was between that of FISH and cytology.2 Although these techniques represent an improvement over routine cytology, their sensitivity remains suboptimal.

Confocal endomicrosopy is a novel and potentially promising imaging modality to diagnose biliary strictures. Confocal imaging provides the ability to visualize mucosa and blood vessels in the bile duct. Although earlier published study14 plus this study together suggest that certain imaging patterns provide an improved ability to distinguish among benign and malignant strictures, the histologic significance of these patterns remains unclear. One important diagnostic feature of confocal images is the reticular network, which is more typical of benign ductular tissue. Multiphoton images plus lymphatic staining of H&E-stained sections together suggest that this network of dark branching bands probably reflects lymphatics rather than blood vessels. There is some evidence that lymphangiogenesis occurs in cholangiocarcinoma,22 which may account for the observation that the reticular pattern tends to be distorted in this type of malignancy. In addition, using the high-definition confocal miniprobe, we observed fluorescein-filled blood vessels containing red blood cells within the wall of a normal bile duct. This suggests that the thick white bands previously associated with carcinoma do not necessarily represent blood vessels, and that the presence of fluorescein-filled blood vessels does not always represent cholangiocarcinoma. There are several limitations with this study. The number of patients limits definite conclusions regarding normal and malignant-appearing patterns using confocal endomicroscopy. In addition, malignant biliary strictures studied here included not just cholangiocarcinoma but also pancreatic cancer and for 1 patient possible metastatic disease. Furthermore, abnormal vasculature may merely represent a paraneoplastic phenomenon. However, the finding of blood vessels containing red blood cells in the wall of a normal bile duct supports the conclusion that blood-filled vessels are not a paraneoplastic phenomenon limited to patients with biliary or pancreatic cancers. As additional studies are performed to establish the usefulness of confocal endoscopy for the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures, it is likely that parallel work will need to be conducted to understand the histologic meaning of the imaging patterns that are observed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: NIH grants DK34989, DK57751, DK45710, and DK61747.

APPENDIX

Miami Criteria for Biliary Imaging

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Fine branching bands (<20 μm) |

Thick branching bands (>20 μm) |

| Reticular network of dark bands |

Dark clumps/glands |

| Vessels <20 μm | Bright vessels > 20 μm, tortuosity |

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement: Dr Jamidar has received honorarium from Cellvizio. The other authors have no competing financial interest to declare.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Website, www.jcge.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1655–1667. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreno Luna LE, Kipp B, Halling KC, et al. Advanced cytologic techniques for the detection of malignant pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1064–1072. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2005;366:1303–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67530-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahrendt SA, Nakeeb A, Pitt HA. Cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2001;5:191–218. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(05)70161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett JJ, Green RH. Malignant masquerade: dilemmas in diagnosing biliary obstruction. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2009;18:207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2008.12.005. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harewood GC. Endoscopic tissue diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:627–630. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32830bf7e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iqbal S, Stevens PD. Cholangiopancreatoscopy for targeted biopsies of the bile and pancreatic ducts. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiung PL, Hardy J, Friedland S, et al. Detection of colonic dysplasia in vivo using a targeted heptapeptide and confocal microendoscopy. Nat Med. 2008;14:454–458. doi: 10.1038/nm1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiesslich R, Burg J, Vieth M, et al. Confocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:706–713. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman A, Goetz M, Vieth M, et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy: technical status and current indications. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1275–1283. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meining A, Saur D, Bajbouj M, et al. In vivo histopathology for detection of gastrointestinal neoplasia with a portable, confocal miniprobe: an examiner blinded analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1261–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kara MA, DaCosta RS, Streutker CJ, et al. Characterization of tissue autofluorescence in Barrett’s esophagus by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20:141–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goetz M, Ziebart A, Foersch S, et al. In vivo molecular imaging of colorectal cancer with confocal endomicroscopy by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:435–446. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meining A, Frimberger E, Becker V, et al. Detection of cholangiocarcinoma in vivo using miniprobe-based confocal fluorescence microscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1057–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rogart JN, Nagata J, Loeser CS, et al. Multiphoton imaging can be used for microscopic examination of intact human gastrointestinal mucosa ex vivo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvaro D, Mancino MG. New insights on the molecular and cell biology of human cholangiopathies. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frierson HF., Jr. The gross anatomy and histology of the gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, Vaterian system, and minor papilla. Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:146–162. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198902000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim JH, Park CK. Pathology of cholangiocarcinoma. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:540–547. doi: 10.1007/s00261-004-0187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Bellis M, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (Part 2) Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:720–730. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Bellis M, Sherman S, Fogel EL, et al. Tissue sampling at ERCP in suspected malignant biliary strictures (Part 1) Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:552–561. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.128132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jailwala J, Fogel EL, Sherman S, et al. Triple-tissue sampling at ERCP in malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51(4 Pt 1):383–390. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(00)70435-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thelen A, Scholz A, Benckert C, et al. Tumor-associated lymphangiogenesis correlates with lymph node metastases and prognosis in hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:791–799. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9774-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.