Abstract

Purpose

To design and evaluate a research mentor training curriculum for clinical and translational researchers. The resulting 8‐hour curriculum was implemented as part of a national mentor training trial.

Method

The mentor training curriculum was implemented with 144 mentors at 16 academic institutions. Facilitators of the curriculum participated in a train‐the‐trainer workshop to ensure uniform delivery. The data used for this report were collected from participants during the training sessions through reflective writing, and following the last training session via confidential survey with a 94% response rate.

Results

A total of 88% of respondents reported high levels of satisfaction with the training experience, and 90% noted they would recommend the training to a colleague. Participants also reported significant learning gains across six mentoring competencies as well as specific impacts of the training on their mentoring practice.

Conclusions

The data suggest the described research mentor training curriculum is an effective means of engaging research mentors to reflect upon and improve their research mentoring practices. The training resulted in high satisfaction, self‐reported skill gains as well as behavioral changes of clinical and translational research mentors. Given success across 16 diverse sites, this training may serve as a national model. Clin Trans Sci 2013; Volume 6: 26–33

Keywords: mentoring, faculty development, evaluation

Introduction

Mentoring plays a vital role in the career development and overall success of researchers across a wide range of fields, including academic medicine.1, 2, 3 In acknowledgement of the essential role that mentors play in the training of future researchers, many training and mentored career development awards require explicit information about the training and expertise of mentors for trainees and scholars. For example, the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) require sites to demonstrate how the mentors of their scholars and trainees will be trained and evaluated (RFA‐RM‐10–020, p. 20); yet research mentoring skills are rarely taught.4 A 2009 survey of Research Education and Career Development Program Directors regarding mentoring programs for clinical and translational (KL2) scholars identified only nine training initiatives across 46 CTSA institutions.5 One reason so many programs have failed to implement training initiatives may be the lack of an established, evidence‐based, user‐friendly mentor training curriculum upon which their training may be based.

To address the need for a proven training curriculum, particularly for the mentors of clinical and translational researchers, a mentor training for clinical and translational researchers was developed. This curriculum was then implemented and tested as part of a randomized, controlled trial, for which 283 mentor–mentee pairs from 16 academic institutions were recruited. Half of the mentors (n = 144) were randomly assigned to participate in mentor training. Here we report on the effectiveness of mentor training for clinical and translational researchers based on evaluation data collected from these participants during and directly following their final training session.

The clinical and translational research mentor training curriculum

In 2010, a multiinstitutional team of six faculty, six staff, and two KL2 scholars from five CTSA institutions adapted a mentor training curriculum to make it applicable to the mentors of clinical and translational researchers. This training curriculum was based on Entering Mentoring, a seminar developed to train current and future biology faculty to become more effective research mentors.6 The Entering Mentoring seminar exposes participants to resources on mentoring; draws on readings, writing, and discussion to clarify ideas and strategies regarding mentoring; creates a forum for discussions on mentoring with colleagues; and provides an opportunity to reflect on mentoring as a scholarly pursuit. Published evaluation of the Entering Mentoring seminar indicates that mentors who participate in this training are more likely to discuss expectations with their mentees, to consider issues of diversity and to seek the advice of their peers in the mentoring process.7 Entering Mentoring has since been adapted to create nine different curricula which target specific disciplines across science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). All of these developed materials have been field‐tested through the Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (CIRTL) at the University of Wisconsin‐ Madison and are available at no charge on the project website (http://www.researchmentortraining.org).

Methods

Using a process similar to the one employed to create the nine mentor training curricula noted earlier, mentor training for clinical and translational researchers was developed over a 6‐month period that included one hour bimonthly conference calls with a curriculum team. During this time, learning objectives and core training activities were outlined, reviewed, and adapted for each training session, which address one of six mentoring competencies: (1) maintaining effective communication, (2) aligning expectations, (3) assessing understanding, (4) addressing diversity, (5) fostering independence, and (6) promoting professional development. The curriculum team strived to make the curriculum more appropriate for the mentors of postdoctoral researchers and junior faculty and focused the content on issues relevant to mentors in clinical and translational research as opposed to those engaged in lab‐based biology research. More extensive facilitation notes and discussion questions were also added. Between calls, the project leader integrated suggested changes and sent them back to the team for review. After a 3‐month period of developing these adaptations, a draft of the resulting curriculum was beta‐tested with a group of 30 faculty and staff, which included many site leaders, at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Association for Clinical and Research Training (ACRT). Feedback was then incorporated into a revised version that was subsequently shared with leaders at all 16 sites and with the curriculum adaptation team for review. The resulting iteration of the curriculum was further tested with the 35 facilitators from the 16 sites who attended a facilitator training workshop. Final modifications of the curriculum were made based on feedback from this train‐the‐trainers event in September 2010.

The curriculum is designed such that small groups of mentors engage in discussion of case studies and activities intended to help them meet a specific set of learning objectives set forth for each competency (Table 1). For example, participants who complete the session on fostering independence should be able to: (1) define independence, describe its core elements, and explain how those elements change over the course of a mentoring relationship; (2) employ various strategies to build their mentee‘s confidence, establish trust, and foster independence; and (3) identify the benefits and challenges of fostering independence. Participants learn to meet these objectives by articulating what independence looks like at each stage of a mentee‘s career, through discussion of a case study, and finally by sharing their views on the benefits and challenges of a mentee reaching independence.

Table 1.

Overview of mentor training for clinical and translational researchers including topics and example learning objectives for each training session

| Training session | Topic | Example learning objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introduction | Establish group dynamics and ground rules |

| Effective communication | Identify different communication styles, learn multiple strategies for improving communication across diverse backgrounds | |

| Session 2 | Establishing expectations | Clearly communicate and align expectations, learn how differences in backgrounds may impact expectations |

| Assessing understanding | Assess mentee's understanding, reasons for lack of understanding, and use strategies to enhance understanding | |

| Session 3 | Addressing diversity | Improve understanding of individual differences and cultures, identify concrete strategies for addressing issues of diversity |

| Fostering independence | Employ strategies to build mentee's confidence, establish trust, and foster independence | |

| Session 4 | Promoting professional development | Develop strategies for guiding professional development and recognize and engage in open dialogue on balancing the competing demands, needs, and interests of mentors and mentees |

| Articulating your mentoring philosophy and plan | Reflect on training experience and any intended changes of behavior or mentoring outlook, articulate approach for working with mentees in the future |

Results

Participation in research mentor training

Sixteen academic institutions were recruited by Dr. Michael Fleming to participate in the clinical and translational research mentor training as part of a randomized controlled trial (University of California‐Davis; University of Colorado‐Denver; Columbia University; University of Illinois‐Chicago; Indiana University; University of Iowa; Mayo Clinic; University of Minnesota; Mount Sinai Medical Center; Northwestern University; The Ohio State University; University of Pittsburgh; University of Puerto Rico; Washington University; University of Wisconsin‐Madison; and Yale University). Each site recruited an average of 18 mentor–mentee pairs to participate in the study. Half of the mentors enrolled in the study were randomly assigned to the intervention arm (n = 144) with a final participation rate of 94%. The other half did not participate in research mentor training. All of the mentors were interviewed prior to, and 6 months postrandomization as part of the main intervention trial. The experimental mentors participated in research mentor training between October 2010 and March 2011 at one of the 16 sites, 15 of which have CTSAs. Although implementation of the curriculum varied slightly from site to site, the most common training schedule included four, 2‐hour sessions with groups of 6–14 mentors spread across 2 months. To standardize delivery of the curriculum at all 16 sites, research mentor training facilitators participated in an intensive one and a half day workshop at the University of Wisconsin‐Madison, prior to implementation. At this workshop, facilitators worked through the entire curriculum, practiced general facilitation approaches and rehearsed facilitating each session using the detailed facilitation notes and discussion questions provided in the curriculum. Implementation was monitored at each site via regular phone calls and surveys administered to facilitators following each session.

All of the participants in the research mentor training were faculty at their respective institutions who were currently mentoring junior investigators engaged in clinical and translational research: 56% full professors, 32% associate professors, and 12% assistant professors. Participants were 65% male (n = 93) and 35% female (n = 51) with 94% White, 2% Asian Indian, 1% African American, 2% Chinese, 1% Japanese, and 1% Korean. Of all of those, 8% were also Hispanic. Participants had a range of prior mentoring experience with 14% having 1–5 years of experience, 25% 6–10 years, 45% 11–20 years, 16% 21–30 years, and 1% over 30 years mentoring experience. Thus, the most common profile for a participant in the training would be a 50‐year old, white male professor with 14.5 years of mentoring experience.

Satisfaction with research mentor training

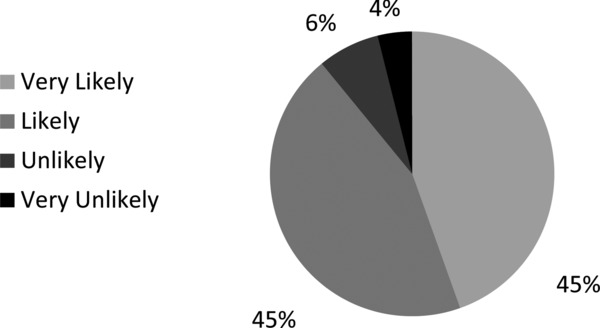

After the mentor training sessions, mentors were asked to complete a 10‐question online survey (Appendix) designed to measure their satisfaction with the training, their learning gains across the six competencies (Table 1) and assess any initial impact on their mentoring philosophy or practices. Individual surveys were emailed to each participant to allow data tracking. Ninety‐four percent of participants completed the survey. Overall, mentors were very satisfied with the training; 88% (n = 112) reported that 8 hours of training was a valuable use of their time. Moreover, 90% of participants responded that they were either likely or very likely to recommend the training to a colleague (Figure 1). Both measures of satisfaction were statistically significant across the overall sample. There were no significant differences in satisfaction based on training implementation site or career status. Satisfaction with the training was independent of overall dosage, although there was a positive correlation between the number of hours attended and the likelihood of participants to indicate that the training was a good use of their time and worth recommending to others.

Figure 1.

Participant satisfaction with research mentor training. Percentage of participants who responded their likelihood to recommend the research mentor training to a colleague (n = 128).

When asked to rate each aspect of the training on a 5‐point scale from very useless to very useful, 97% rated the facilitated discussions during the training sessions as useful or very useful; 98% rated sharing ideas with colleagues as useful or very useful, and 91% rated the case studies as useful or very useful. Other aspects of the training included activities (i.e., making lists, role‐play, drafting compact), readings and resources, which were respectively rated 56%, 59%, and 66% as useful or very useful. One participant reported:

“Many of us mentor routinely but never think about the process in a formalized manner. These sessions provided useful focus to identify and address key and current mentoring issues, particularly through the discussion of the case studies. They also allowed participants to articulate their mentoring philosophy, to hear and share others’ mentoring philosophies, and hopefully to integrate some of the approaches and philosophies into their own mentoring paradigm and practices.”

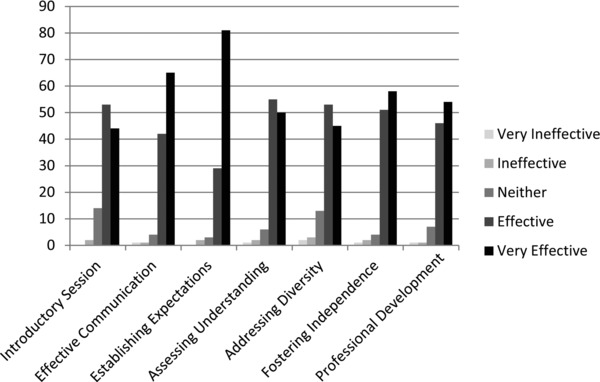

At least 84% of the participants rated each session as effective or very effective on a 5‐point scale (n = 97, Figure 2). The session addressing the establishing expectations competency received the highest marks overall, with 96% of participants rating it as effective (n = 29) or very effective (n = 81); the addressing diversity session was rated the lowest, but 84% of participants still rated it as effective (n = 53) or very effective (n = 45).

Figure 2.

Participant ratings of mentoring session effectiveness. Percentage of respondents rating the indicated research mentor training session for its effectiveness (Scale 1–5; 1 Very Ineffective, 3 Neither Effective nor Ineffective, 5 Very Effective; n = 116).

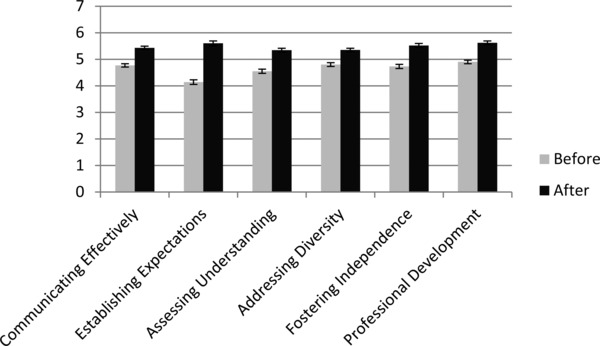

Learning gains from research mentor training

As part of the end‐of‐session survey, mentors were asked to retrospectively rate their skill levels in each competency on a Likert‐type scale of 1–7 (1—Not at all Skilled, 4—Moderately Skilled, 7—Extremely Skilled), thus rating their perceived skill level before and after the training. Self‐reported data indicate statistically significant gains in each competency (p = 0.001; Figure 3) with some variation in learning gains by training implementation site. The highest and lowest skills gains parallel the topics which were rated most and least effective, with the highest skill gains in establishing expectations (+1.46) and the lowest in addressing diversity (+0.55).

Figure 3.

Participant learning gains across six mentoring competencies. Average retrospective rating of mentor self‐reported learning gains across the indicated competency before and after the training (Scale 1–7; 1 Not at all Skilled, 4 Moderately Skilled, 7 Extremely Skilled; n = 125). Self‐reported data indicates statistically significant skills gains in each competency (p ≤ 0.001; paired t‐tests of the post minus prescores).

In response to an open‐ended question about the impact of the training on their mentoring, participants self‐reported learning gains such as:

“It made me realize that some fellows falling short of my expectations may have been because I did not present these to them clearly. It also made me realize that many mentees may not have thought clearly about their goals and expectations and these should be delineated at the outset of the relationship with the mentee.”

“It has helped me to understand that being a good mentor is not only about thriving in science at any cost, but rather nurturing the growth of my mentees and understanding what they expect from this relationship and help[ing] them achieve it.”

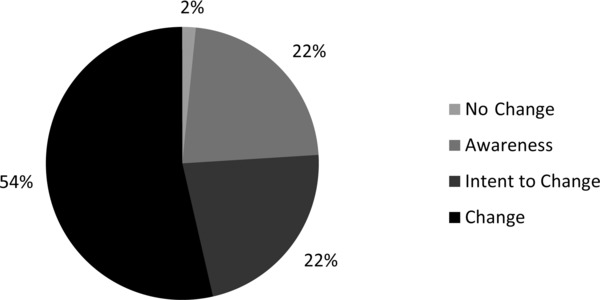

Impact of research mentor training on mentor awareness and behaviors

In addition to the posttraining survey, reflection logs that participating mentors completed throughout the training allowed assessment of changes in mentoring behaviors. At the beginning of Sessions 2, 3, and 4 (Table 1), participants were instructed to provide a written reflection on any changes considered or implemented in their mentoring practices since the last session. The length of time between these sessions varied across the 16 sites. A total of 125 mentors (92%) completed the reflections, which were analyzed qualitatively for levels of change (Figure 4). The reflections from each participant were read as a set by two independent researchers with an interrater reliability of 92%. Each reflection was assigned to one of four categories based on the stages of change: no change, awareness, intent to change, and change. Participants were assigned these stages of change based on the highest level of change demonstrated within their set of reflections. These stages of change are based on those used to describe smoking cessation and other areas such as diversity8, 9 and are described as following:

No Change: mentor does not mention implementation of, or consideration of, any new mentoring practice since his or her last session;

Awareness: mentor mentions thinking about or considering an aspect of the training but does not note plans to implement a change;

Intent to Change: mentor mentions a plan or desire to implement a new behavior in his or her mentoring;

Change: mentor mentions a change that he or she has already executed or is currently implementing.

Figure 4.

Impact of research mentor training on mentor awareness, intent, and behavioral change. Percentage of participants who described a change in awareness, intent, or behavior in their mentor practices during the window of training (n = 125). Mentors were asked to reflect on their mentoring at the start of each session. These reflections were analyzed qualitatively for evidence across four levels of change: no change, awareness, intent to change, and change.

The following excerpts from the reflection logs illustrate three of the stages:

Awareness:

“I thought about how I might adapt my mentoring based on cultural differences among mentees. I also thought about whether I was giving my mentees sufficient time or whether I had sufficient time to be a mentor to so many mentees.”

“I did consider making a more formal compact with my mentee as we begin a mentoring relationship.”

Intent to Change:

“In the future, I will try to make it my policy to meet with mentees away from my office, so as to minimize distractions and foster active listening. Also, it might be a good idea to interact with mentees more away from the office.”

“Specifically, I want to focus more on having my mentees become more independent, both in their current research projects and in their development as a scientist/researcher.”

Change:

“I have altered my style of guiding a PhD student to stay on schedule with her research. In my latest meetings, I approached the discussion from the standpoint of ‘how can I help’ rather than ‘why didn't you keep to the plan?’ The PhD and I worked out a better approach to stay on schedule.”

“Yes, making an even more conscious effort to remain open‐minded and practice as much active listening as possible to assure mentee's thoughts/ideas/concerns/problems are being heard and understood.”

Over half of the mentors reported they had implemented a change in their mentoring practice and only 2% of the responses noted no change at all.

Discussion and Conclusion

Here we report on the development, implementation, and evaluation of a research mentor training curriculum for the mentors of clinical and translational researchers, adapted from the published mentor training curriculum, Entering Mentoring. 6 Over 100 mentors from 16 academic sites participated in the 8‐hour training. Although the majority of participants in the training were senior faculty with at least 15 years of mentoring experience, 88% reported that the training was worth their time, thereby dispelling a common concern that faculty mentors may not find mentor training a valuable use of their limited time (Figure 1). Other concerns and obstacles identified as potential impediments to the success of this study are outlined below, accompanied by study findings that refute them.

(1) Seasoned faculty will resist the suggestion that they have anything new to learn about mentoring (i.e. “old dogs” are not interested in learning new tricks).

Finding: The training was well received by men, women, assistant, associate, and full professors with a wide range of prior mentoring experience.

(2) Mentoring skills are not learned in a formal training program but rather are experientially learned in mentor–mentee dyads.

Finding: Mentoring skills can be learned and improved upon using a formal structured curriculum. As with most learning experiences, learning to be an effective research mentor is best accomplished when the training combines participation in a formal course/curriculum and engagement in the practice of mentoring itself.

(3) Time is a major barrier. Senior faculty are too busy to participate in an 8‐hour training.

Finding: Senior mentors did participate in the 8‐hour research mentor training program delivered over four sessions and actually reported it a valuable use of their time. Seventy‐eight percent of the mentors completed all 8 hours of training. Busy, successful people do make time for educational activities they find valuable.

(4) Institutional resources to implement mentor training programs are scarce.

Finding: Institutions participating in the study did find resources and faculty to implement the mentor training program. None of the 16 institutions (except the lead institution UW‐Madison) that participated in the trial had a specific grant to support the training. Each site invested internal resources to recruit the participants, collect the data, and implement the training.

(5) One curriculum cannot be effective across 16 large academic institutions with varied cultural differences.

Finding: The curriculum was uniformly effective at getting training participants to reflect, discuss, and engage with other mentors about real life experiences. The curriculum was found to be generalizable to all the institutions that participated.

There are a number of aspects of the curriculum that require further analysis. First, the highest and lowest skill gains parallel the sessions rated most and least effective, with the highest skill gain in establishing expectations and the lowest in addressing diversity. This may be due to the varied structure and focus of these two sessions. For example, in the “Establishing Expectations” session, mentors have the opportunity to apply what they have learned. They are asked to review written examples of mentor–mentee compacts and are asked to draft their own for use with their trainees. This is a tangible activity with a clear product, which mentors can put into practice with their trainees in written or verbal form. In contrast, the diversity session is more heavily focused on discussions aimed at raising awareness of the challenges and opportunities that differences in race, gender, and background can present in a mentoring relationship. Although this awareness is critical, mentors may leave the session without a clear sense of how to operationalize it. Literature supports the notion that learning is most effective when the learner has an opportunity to apply what they have learned in a relevant context.10 To address this need, the current Mentor Training for Clinical and Translational Researchers11 will be augmented with resources from other mentor training programs, such as the University of San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute Mentor Development Program,11 as well as from information gleaned from another University of Wisconsin‐Madison CTSA Administrative Supplement on Mentoring.

Second, we identified site variation in the learning gains for each competency. However, preliminary analyses are unable to differentiate among potential mechanisms driving the observed variation, such as differing numbers of participants by site, or the extent to which there are ceiling effects in the scale. The ongoing randomized trial will provide additional data to address these issues. This includes use of the Mentoring Competency Assessment (MCA) measure that contains multiple items for each mentoring competency. This instrument was administered to mentors at baseline and 6 months postrandomization.

Finally, beyond the reported learning gains, our survey data point to an interesting evolution in mentors’ awareness, intentions, and mentoring approaches and behavior during the course of the training (Figure 4). Over 50% of the mentors reported a specific change in their mentoring practice between the first and final session of the training. This finding is perhaps the most compelling data supporting a measurable impact of the described mentor training. Analysis of the mentoring trial's larger dataset will lend insight into whether such changes in practice were sustained posttraining, if changes in awareness and intent were acted upon, and most importantly, if these changes are recognized by their mentees.

Sources of Funding

The project described was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Other disclosure

We have published a printed version of Mentor Training for Clinical and Translational Researchers with W.H. Freeman and Company. The curriculum is also freely available for download via a mentoring website currently under development by the UW‐Madison Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (https://mentoringresources.ictr.wisc.edu).

Ethical Approval

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the University of Wisconsin‐Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Disclaimer

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Jason Baker, Michael Hammer, Stephanie Schiro, and Orly Vardeny for their work on the curriculum; Karin Silet and Christine Sorkness for their feedback on the manuscript, and Vansa Shewakramani for her assistance with data analysis. In addition, the authors thank:

Official Collaborators/Participating Investigators

All CTSA Mentor Training Trial Site Leaders:

Adriana Báez Bermejo, Melissa D. Begg, Philip Binkley, Barb Brandt, Ellen Burnham, Suzanne Campbell Delapp, Marc Drezner, Julie Eichenberger‐Gilmore, Janice Gabrilove, Jane Garbutt, Rubén García, Charles Huskins, Kurt Kroenke, Bruce Rollman, Gary Rosenthal, William Schnaper, Julie Schweitzer, Eugene Shapiro, Christine Sorkness, Stephanie Vecchiarelli.

All CTSA Mentor Training Trial Facilitators:

Adriana Báez, Matthew J. Bair, Dian Baker, Melissa Begg, Paula Carney, Nisha Charkoudian, Herb Chen, Lisa Christian, Faith Davis, Tracy Davis, Tom De Fer, Clemente Diaz, Luisa Dipietro, Esam El Fakahany, Kristi Ferguson, Janice Gabrilove, Jane Garbutt, Rubén García, Lois Geist, Stacie Geller, Jo Handelsman, Richard Horuk, Charlie Huskins, Kurt Kroenke, Jane Mahoney, Richard McGee, Marc Moss, Patrick O'Connor, Bruce Rollman, Julie Schweitzer, Janet Shandling, Eugene Shapiro, Stephanie Studenski, Robert Tillman, Anne Marie Weber‐Main, Jack Westfall, Margaret Wierman, Karla Zadnik, Karen Zier.

Appendix: CTSA Post–Mentor Training Survey

Question 1 How effective would you rate each research mentor training session/topic in helping you improve your mentoring skills?

| Very ineffective | Ineffective | Neither effective nor ineffective | Effective | Very effective | N/A did not attend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Introductory session (get to know each other, establish ground rules, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 1: Maintaining effective communication (constructive feedback, communication styles, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 2: Establishing expectations (aligning expectations, mentoring compacts, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 2: Assessing understanding (root causes, share strategies, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 3: Addressing diversity (share experience as outsider, discuss diversity studies, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 3: Fostering independence (core elements of independence, share strategies, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 4: Promoting professional development (different career tracks, individual development plans, etc.) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Session 4: Articulating your mentoring philosophy and plan | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Make‐up session | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Question 2 How useful were each of the following elements in the research mentor training process?

| Very useless | Useless | Neutral | Useful | Very useful | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case studies | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Facilitated discussions | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Activities (making lists, role‐play, drafting compacts, etc) | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Readings | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Resources | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Sharing ideas with colleagues | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Question 3 Overall, were the 8 hours you spent in research mentor training a valuable use of your time?

Yes

No

Question 4 What do you think are the greatest strengths of the mentor training sessions?

Question 5 What do you think needs the most improvement in the mentor training sessions?

Question 6 How likely is it that you would recommend the mentor training sessions to a colleague?

Very Likely

Likely

Unlikely

Very Unlikely

Question 7 Overall, how effective were the facilitators in guiding discussion during your research mentor training sessions?

Very Ineffective

Ineffective

Neither Effective nor Ineffective

Effective

Very Effective

Question 8 Please provide a specific example to illustrate your rating of facilitator effectiveness above.

Question 9 Please rate how skilled you feel you were BEFORE the research mentor training sessions and how skilled you feel you are NOW in each of the following areas: (Think about your skills generally).

| Not at all 1 | 2 | 3 | Moderately 4 | 5 | 6 | Extremely 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communicating effectively—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Communicating effectively—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Establishing expectations—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Establishing expectations—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Assessing understanding—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Assessing understanding—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Addressing diversity—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Addressing diversity—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Fostering independence—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Fostering independence—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Promoting professional development—BEFORE | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| Promoting professional development—NOW | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

Question 10 Did the research mentor training sessions have an impact on the way you mentor? In other words, have you changed your behavior, or do you plan to change your behavior in some way? If so, please include an example. If not, why?

Previous presentation: A subset of data reported in this paper was presented at the Association for Clinical Research Training/American Federation for Medical Research/Society for Clinical and Translational Science Joint Meeting in April 2011.

References

- 1. Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine. A systematic review. JAMA. 2006; 296(9): 1103–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Steiner JF, Curtis P, Lanphear BP, Vu KO, Main DS. Assessing the role of influential mentors in the research development of primary care fellows. Acad. Med. 2004; 79(9): 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palepu A, Friedman RH, Barnett RC, Carr PL, Ash AS, Szalacha L, Moskowitz M. A junior faculty members’ mentoring relationships and their professional development in U.S. medical schools. Acad. Med. 1998; 73(3): 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johnson MO, Subak LL, Brown JS, Lee KA, Feldman MD. An innovative program to train health sciences researchers to be effective clinical and translational research mentors. Acad. Med. 2010; 85(3): 484–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silet KA, Asquith P, Fleming MF. Survey of mentoring programs for KL2 scholars. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2010; 3(6): 299–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Handelsman J, Pfund C, Lauffer S, Pribbenow C. Entering Mentoring: A Seminar to Train a New Generation of Scientists. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pfund C, Maidl Pribbenow C, Branchaw J, Miller Lauffer S, Handelsman J. Professional skills. The merits of training mentors. Science. 2006; 311(5760): 473–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self‐change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1983; 51(3): 390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carnes M, Handelsman J, Sheridan J. Diversity in academic medicine: the stages of change model. J. Women‘s Health. 2005; 14(6): 471–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bransford JD, Brown AL, Cocking RR (Eds.). How people learn: brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pfund C, House S, Asquith P, Spencer K, Silet K, Sorkness C. Mentor training for clinical and translational researchers. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Feldman MD, Huang L, Guglielmo BJ, Jordan R, Kahn J, Creasman JM, Wiener‐Kronish JP, Lee KA, Tehrani A, Yaffe K, Brown JS. Training the next generation of research mentors: the University of California, San Francisco, Clinical & Translational Science Institute Mentor Development Program. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2009; 2(3): 216–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]