Abstract

Background & Aims

We sought to estimate the need for surgery in an American population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease.

Methods

The medical records of 310 incident cases of Crohn’s disease from Olmsted County, Minnesota, diagnosed between 1970 and 2004, were reviewed through March 2009. Cumulative incidence was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and associations between baseline factors and time to first event were assessed using proportional hazards regression and expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results

Median follow-up per patient was 12.0 years. One hundred fifty-two patients underwent at least one major abdominal surgery, 65 had at least two surgeries, and 32 had at least three. The cumulative probability of major abdominal surgery was 38%, 48% and 58% at 5, 10 and 20 years after diagnosis, respectively. Baseline factors significantly associated with time to major abdominal surgery were: ileocolonic (HR, 3.3), small bowel (HR, 3.4) and upper gastrointestinal (HR, 4.0) extent, relative to colonic alone; current cigarette smoking (HR, 1.7), male gender (HR, 1.6), penetrating disease behavior (HR, 2.7), and early corticosteroid use (HR=1.6). Major abdominal surgery rates remained stable, with 5-year cumulative probabilities in 1970–74 and 2000–04 of 37.5% and 35.1%, respectively.

Conclusions

The cumulative probability of major abdominal surgery in this population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease approached 60% after 20 years of disease, and many patients required second or third surgeries. Non-colonic disease extent, current smoking, male gender, penetrating disease behavior, and early steroid use were significantly associated with major abdominal surgery.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, surgery, natural history, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease is a disabling condition over time. Many patients with Crohn’s disease will require surgical intervention during the disease course1. Before the era of biologics, the requirement for surgery in referral center data ranged from 17% to 35% within 5 years after initial diagnosis, while it ranged from 18% to 33% within 5 years after diagnosis in the most recent studies2. However, most of these studies report surgical trends in patients seen at referral centers, and thus may be influenced by referral bias. Population-based studies may better reflect the true spectrum of an illness. Seven different population-based cohorts from the United States (US), Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Wales, Canada, as well one Europe-wide population-based study reported the need for surgery in Crohn’s disease2, 3. In a Danish population-based cohort, the probability of surgical resection within 15 years after diagnosis was 70%4. More recently, in a Norwegian population-based study, the cumulative probability of surgery during the first 10 years was 37.9%5. Overall, before the era of anti-TNFα therapies, the rate of surgical requirements ranged from 27% to 61% at 5 years2.

In the era of biologics and widespread use of immunomodulators, long-term data from population-based studies on the need for surgery in Crohn’s disease are scarce6–8. In addition, conflicting data exist regarding changes in surgery rates in Crohn’s disease over the past decades3, 9, 10. Risk factors for surgery in Crohn’s disease were assessed in two Scandinavian population-based cohorts. Notably, disease location, stricturing or penetrating disease behavior, and early use of steroids or thiopurines were independent factors affecting likelihood of intestinal surgery5, 9, 11. Risk factors associated with the need for surgery in Crohn’s disease have never been formally investigated in US population-based cohorts.

The aim of this study was therefore to update the cumulative probability of surgery in Crohn’s disease in a well-defined population-based cohort, to identify baseline factors associated with need for surgery, and to evaluate changes in surgery rates over time. We also investigated the indications for and type of surgery performed for Crohn’s disease.

METHODS

Patient Selection

The population-based inception cohort of subjects with Crohn’s disease has been previously described12, 13 and was updated through March 2009 for this study.

Study Setting

Olmsted County is situated in southeastern Minnesota and had approximately 124,000 people at the 2000 U.S. Census. In 2000, 89% of the population was non-Hispanic white. Although 25% of county residents are employed in health care services (vs. 8% nationwide), and the level of education is higher (30% have completed college vs. 21% nationwide), the residents of Olmsted County are otherwise socioeconomically similar to the U.S. white population14.

Rochester Epidemiology Project

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a unique medical records linkage system developed in the 1960s and funded in part by the National Institutes of Health. It exploits the fact that virtually all of the health care for the residents of Olmsted County is provided by two organizations: Mayo Medical Center (Mayo Clinic and its hospitals, Rochester Methodist and Saint Marys); and Olmsted Medical Center (a multispecialty clinic and its hospital, Olmsted Community Hospital). Diagnoses generated from all outpatient visits, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, nursing home visits, surgical procedures, diagnostic studies, autopsy examinations, and death certi cates for all county residents seen since 1908 are recorded in a central diagnostic index14, 15. In any three-year period, over 90% of county residents are examined at one of the two health care systems14. Thus, it is possible to identify all diagnosed cases of a given disease, and all diagnostic examinations, including radiological studies, performed in these subjects. The resources of the REP have been used to identify Olmsted County residents diagnosed with Crohn’s disease from 1940 to 200412, 13.

Case Ascertainment

With approval from the Institutional Review Boards of Mayo Foundation and Olmsted Medical Center, the records of 310 patients who had not denied permission for research access to their medical records and who were rst diagnosed with Crohn’s disease between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 2004 were reviewed. Demographic information including date of birth, date of symptom onset, date of diagnosis, disease type and extent were previously obtained12, 13. Using the date of symptom onset to the last date of follow-up (through March 2009), the duration of follow-up was recorded for each patient. Major abdominal surgery was defined as any surgery except perianal surgery or endoscopic dilation.

Statistical Analysis

Some demographic and clinical factors such as age, gender, smoking status, family history, and extraintestinal manifestations were recorded at the date of diagnosis, while disease extent, disease behavior, perianal disease, and medication use during the first 90 days after diagnosis were recorded. The analyses of the association of these factors with time to first major abdominal surgery were thus considered two different “start times” (relative time zero): the date of diagnosis, and separately 90 days post-diagnosis. The overall cumulative incidence (%) of major abdominal surgery, bowel resection, and ileal/ileocolonic resection were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method (using date of diagnosis as the start time), and 95% confidence intervals based on the log transformation with modified lower limit method. Among patients with any one of these events, the cumulative incidence of a second event was estimated using the same method, using the date of first event as the start time, and similarly for cumulative incidence of a third event among patients with two events. Types and indications of major abdominal surgery were summarized descriptively (n, %). Univariate associations between baseline factors and time to first event were assessed using proportional hazards regression, and expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Multiple variable proportional hazards models were also examined, and in these models the start time was 90 days post-diagnosis. The association between medication use and time to first major abdominal surgery was evaluated using Cox proportional hazards regression models (both univariate and multiple variable). Temporal changes in the time to initial major abdominal surgery were assessed (5 year periods beginning in 1970) using the earliest period (1970–74) as the reference level. The number of surgeries per year of follow-up for major abdominal surgery, bowel resection, and ileal/ileocolonic resection were also summarized descriptively, and temporal trends in these rates assessed using a generalized linear regression model (assuming a negative binomial distribution to accommodate over-dispersion, logit link function, and log duration of follow-up as an offset). The analyses were performed using SAS® (version 9.2). Supplementary Table 1 summarizes the patient numbers used in the various analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics at Time of Diagnosis

One hundred fifty-six (50%) of the 310 patients were male (Table 1). According to the Montreal classi cation16, only 33 patients (10%) were younger than 16 years old at diagnosis (A1), 177 (57%) were between 17 and 40 years old at diagnosis (A2), and 100 (32%) were older than 40 years at diagnosis (A3). Approximately one third of patients each had ileitis [96 (31%)], colitis [102 (33%)], or ileocolitis [103 (33%)] at the time of diagnosis, with the remaining 7 (2%) being gastroduodenal. Two hundred forty-nine (81%) of patients had non-stricturing and non-penetrating disease (B1), 14 patients (5%) had stricturing disease (B2), and 43 (14%) had penetrating disease (B3). Perianal disease (p) was noted in 51 patients (17%) prior to or within 90 days of Crohn’s disease diagnosis. One hundred fifty-six patients (52%) were non-smokers, while 98 patients (33%) were current smokers. A familial history of IBD was reported by 43 patients (14%). Extra-intestinal manifestations at the time of diagnosis were noted in 46 patients (15%). Median follow-up subsequent to Crohn’s disease diagnosis in all patients was 12.0 years, and in the 158 patients with no major surgeries, it was 9.8 years (range, 2 months to 38.1 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 310 patients from Olmsted County, Minnesota, at the time of their Crohn’s disease diagnosis.

| Factors at Crohn’s diagnosis | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 156 (50.3) |

| Female | 154 (49.7) |

|

| |

| Age | |

| Less than 16 years (A1) | 33 (10.6) |

| Age between 17 and 40 years (A2) | 177 (57.1) |

| Age more than 40 years (A3) | 100 (32.3) |

|

| |

| Disease Location | |

| Small Bowel (L1) | 96 (31.2) |

| Colitis (L2) | 102 (33.1) |

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 103 (33.4) |

| Gastroduodenal (L4) | 7 (2.3) |

| Not documented | 2 |

|

| |

| Disease behavior | |

| Non-Stricturing/Non-Penetrating (B1) | 248 (81.3) |

| Stricturing (B2) | 14 (4.6) |

| Penetrating (B3) | 43 (14.1) |

| Not documented | 5 |

|

| |

| Perianal Disease prior to or within 90 days of diagnosis | |

| Yes | 51 (16.7) |

| No | 254 (83.3) |

|

| |

| Smoking history | |

| Current smokers | 98 (32.9) |

| Former smokers | 45 (15.1) |

| Non-smokers | 155 (52.0) |

| Not documented | 12 |

|

| |

| Family History of IBD | |

| Yes | 43 (14.4) |

| No | 255 (85.6) |

| Not documented | 12 |

|

| |

| Extra-intestinal manifestation | |

| Yes | 46 (15.1) |

| No | 259 (84.9) |

| Not documented | 5 |

Cumulative Incidence of Major Abdominal Surgery

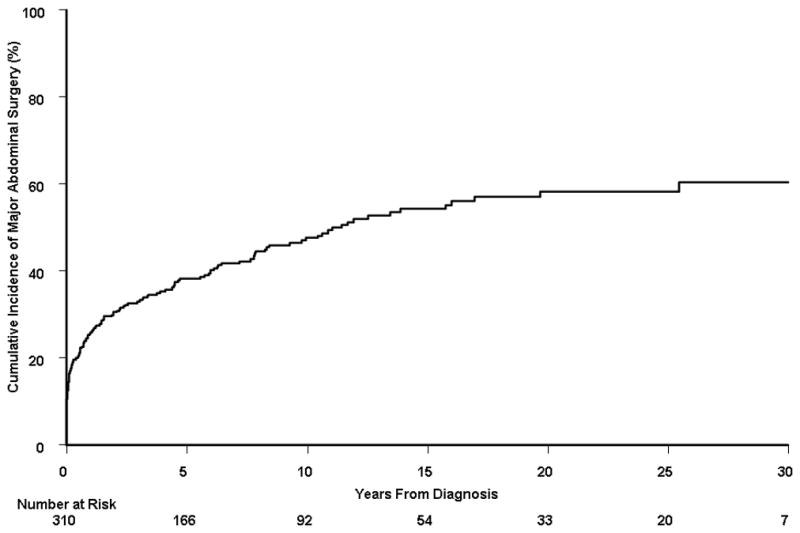

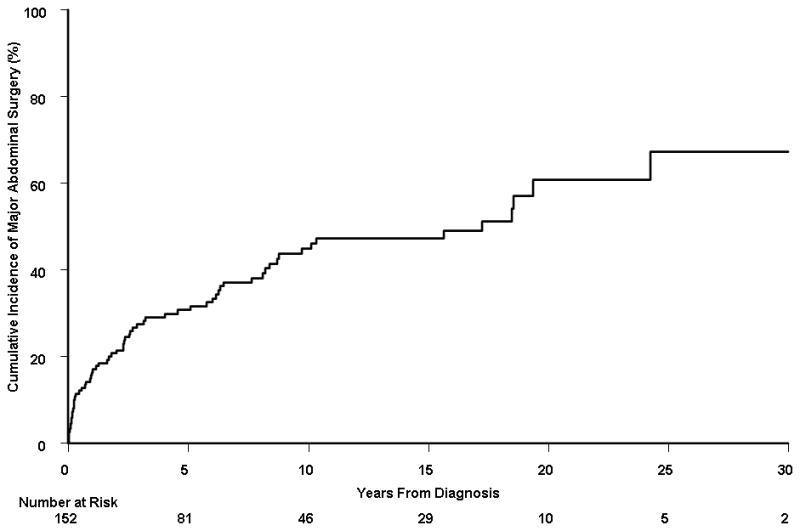

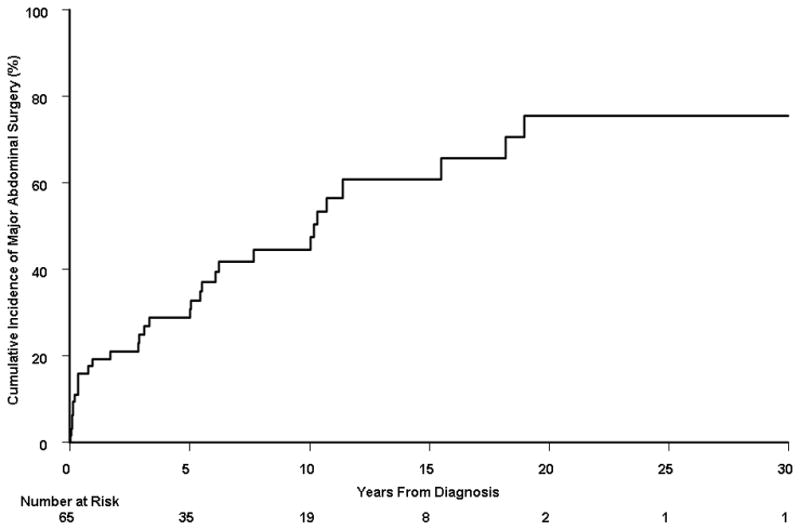

Among the 310 patients, 152 subjects underwent at least one major abdominal surgery at the time of or after the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The median number of major abdominal surgeries per person-year of follow-up was 0.0 (interquartile range, 0.0 – 0.14), with a mean (± standard deviation) of 0.25 (± 1.32). The cumulative probability of first major abdominal surgery from time of diagnosis was 38.2% (95% CI, 32.5%–43.5%), 47.6% (41.3%–53.3%), 58.3% (50.6%–65.0%), and 60.5% (51.8%–71.0%) at 5, 10, 20, and 30 years, respectively (Figure 1A). Among these 152 patients, 65 (43%) underwent a second major abdominal surgery after having a first major surgery. The cumulative probability of second major abdominal surgery from time of first surgery was 30.8% (95% CI, 22.6%–38.2%), 44.9% (35.0%–53.3%), 60.8% (45.8%–72.0%), and 67.3% (47.1%–83.5%) at 5, 10, 20, and 30 years, respectively (Figure 1B). Among the 65 patients with 2 major abdominal surgeries, 32 patients (49%) underwent a third surgery. The cumulative probability of third major abdominal surgery from time of second surgery was 28.8% (95% CI, 16.1%–39.8%), 44.6% (28.8%–57.1%), 75.5% (52.1%–91.5%), and 75.5% (52.1%–92.3%) at 5, 10, 20, and 30 years, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

A) Cumulative probability of first major abdominal surgery from time of diagnosis among 310 Crohn’s disease patients diagnosed in Olmsted County, Minnesota between 1970 and 2004; B) cumulative probability of second major abdominal surgery from time of first major abdominal surgery (n = 152); and C) cumulative probability of third major abdominal surgery from time of second major abdominal surgery (n = 65).

Type of First Major Abdominal Surgery

The first major abdominal surgery included an ileal or ileocecal resection in 110 out of 152 patients (72.4%), and total proctocolectomy in 16 patients (10.5%) (Table 2). Subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis, a diverting procedure, and drainage of abscess were performed in 10, 9 and 8 patients, respectively. Other initial abdominal surgeries included abdominal exploration without bowel resection, gastrojejunostomy, segmental colectomy, right hemicolectomy, jejunal resection, and stricturoplasty.

Table 2.

Type of first major abdominal surgery performed in the 152 patients from Olmsted County, Minnesota, who underwent at least one major abdominal surgery.

| Surgical procedure | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Ileal or ileocecal resection | 110 (72.4) |

| Total proctocolectomy with Brooke or Koch pouch | 16 (10.5) |

| Subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis | 10 (6.6) |

| Loop ileostomy or loop colostomy | 9 (5.9) |

| Drainage of abdominal abscess | 8 (5.3) |

| Abdominal exploration without bowel resection | 8 (5.3) |

| Gastrojejunostomy | 3 (2) |

| Right hemicolectomy | 2 (1.3) |

| Jejunal resection | 1 (0.7) |

| Stricturoplasty | 1 (0.7) |

Note: one patient could undergo more than one surgical procedure at the same time.

The first patient to be operated on via laparoscopic techniques underwent ileocecal resection on December 23, 1997. The first abdominal surgery was performed laparoscopically in 24 patients (16%) until March 2009.

Indications for First Major Abdominal Surgery

The main indications for surgery were obstruction or medical therapy failure in 37 out of 152 patients (24%) each, perforation or abscess in 10% each, fistulizing disease in 8% of subjects, intestinal cancer in 4% of patients, and severe perianal disease, bleeding or severe pain in 3% each (Table 3).

Table 3.

Indication for first major abdominal surgery in the 152 patients from Olmsted County, Minnesota, who underwent an initial major abdominal surgery.

| Indication | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Medical therapy failure | 38 (25) |

| Obstruction | 37 (24) |

| Perforation | 15 (10) |

| Abdominal abscess | 15 (10) |

| Fistulizing disease | 12 (8) |

| Intestinal cancer | 6 (4) |

| Severe perianal disease | 5 (3) |

| Bleeding | 5 (3) |

| Severe pain | 5 (3) |

| Mass/polyp seen on imaging studies or endoscopy | 4 (2) |

| Extraintestinal complication | 2 (1) |

| Toxic megacolon | 1 (1) |

| Necrosis of the bowel | 1 (1) |

| Miscellaneous | 6 (4) |

Factors Associated With Major Abdominal Surgery

The association of baseline factors known at diagnosis with the time to surgery was assessed in all 310 patients using univariate proportional hazards regression (Supplementary Table 2). The presence of any extra-intestinal manifestation at the time of Crohn’s diagnosis was negatively associated with time to major abdominal surgery (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.3–0.9). Male gender was associated with a borderline significant increased risk of surgery (HR,1.3; 95% CI, 1.0, 1.8, p=0.07). Age, smoking status, and a family history were not significantly associated with time to major abdominal surgery.

The association of factors known within the first 90 days of the diagnosis (disease extent, disease behavior, perianal disease status, and early medication use) were also assessed using proportional hazards regression (start time at 90 days post-diagnosis) (Supplementary Table 2). A total of 249 patients were included in these analyses (2 patients did not have a major surgery but had fewer than 90 days of follow-up while another 59 patients had their first major surgery less than 90 days from diagnosis). Relative to patients with colonic extent, patients with isolated terminal ileal disease or ileocolonic extent were at an approximately 3-fold increased risk of having major abdominal surgery (HR, 3.1; 95% CI, 1.8–5.4 for both extent categories). Upper gastrointestinal disease was associated with an almost 4-fold increased risk of major abdominal surgery (HR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.1–12.5). Overall, disease behavior was associated with time to initial major abdominal surgery (p=0.04). Penetrating disease behavior noted during the 90-day post-diagnosis period relative to non-penetrating/non-stricturing behavior was associated with an increased risk of having major abdominal surgery (HR, 2.8, 95% CI, 1.2–6.4). Medication use within the first 90 days and presence of perianal disease were not significantly associated with major abdominal surgery.

A multiple variable proportional hazards regression model was used to identify factors significantly associated with time to surgery (Table 4). A total of 249 patients were included in this analysis; specifically, patients with at least 90 days of follow-up after diagnosis and who had not had a first major abdominal surgery within 90 days of the diagnosis. Male gender (HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.02–2.4); current smoking status at the 90-day post-diagnosis baseline (HR relative to never, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1–2.7); disease extent with ileocolonic disease extent (HR relative to colonic extent, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.8–5.8), small bowel extent (HR, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.9–6.1), and upper gastrointestinal extent (HR, 4.0; 95% CI, 1.2–13.8) were among the variables included in the multiple variable model. Although overall disease behavior was modestly associated with risk for major abdominal surgery (p=0.08), an increased risk associated specifically with penetrating disease behavior (HR relative to non-penetrating/non-stricturing behavior, 2.8; 95% CI, 1.1–6.7, p=0.03)) observed. Along with corticosteroid use within 90 days of the diagnosis (HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.03–2.5), the multiple variable model implied these variables (Table 4) were independently associated with time to first major abdominal surgery.

Table 4.

Multiple variable model hazard ratios for risk of first major abdominal surgery associated with baseline factors and factors known by 90 days post-CD diagnosis (n=249).

| Factors at Crohn’s diagnosis | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Overall p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.6 | 1.02–2.4 | 0.04 | |

| Female | 1.0 | Ref. | ||

|

| ||||

| Disease Location | ||||

| Small Bowel (L1) | 3.4 | 1.9–6.1 | <0.0001 | <0.001 |

| Colitis (L2) | 1.0 | Ref. | ||

| Ileocolonic (L3) | 3.3 | 1.8–5.8 | <0.0001 | |

| Gastroduodenal (L4) | 4.0 | 1.2–13.8 | 0.03 | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Current smokers | 1.7 | 1.1–2.7 | 0.02 | 0.046 |

| Former smokers | 1.0 | 0.5–1.9 | 0.90 | |

| Non-smokers | 1.0 | Ref. | ||

|

| ||||

| Disease Phenotype | ||||

| Penetrating | 2.7 | 1.1–6.7 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Stricturing | 1.4 | 0.2–10.4 | 0.74 | |

| Non-Penetrating/Non-Stricturing | 1.0 | Ref. | ||

|

| ||||

| Steroids within 90 days of diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 1.6 | 1.03–2.5 | 0.04 | |

| No | 1.0 | Ref. | ||

Association of Medication Use with Cumulative Probability of Surgery

Among this cohort of 310 patients, the prevalence of any medication use was: 70% for 5-aminosalicylates; 33% for antibiotics; 62% for corticosteroids; 25% for immunosuppressive medications, and 15% for anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy. In univariate models, the use of 5-aminosalicylates was associated with a reduced risk for surgery (HR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3–0.6), while use of antibiotics (HR, 5.2; 3.4–8.1), corticosteroids (HR, 5.3; 3.7–7.5), and anti-TNF therapy (HR, 2.7; 1.4–5.4) were all significantly associated with time to first surgery. The association between immunosuppressive use and time to first major abdominal surgery was not significant (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.7–2.0). The multiple variable model, which included all medications simultaneously, showed essentially the same results (data not shown).

Among patients who had already undergone a first major abdominal surgery, the use of antibiotics (HR, 8.8; 95% CI, 3.9–19.7) and corticosteroids (HR, 2.5; 95% CI, 1.3–4.6) were significantly associated with time to second abdominal surgery in univariate analysis. Associations between 5-aminosalicylate use (HR, 1.6; 95% CI, 0.9–2.7), immunosuppressives (HR, 1.3; 95% CI, 0.7–2.6), and anti-TNF agents (HR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.1–3.9) and second abdominal surgery were not significant. Similar findings were seen in the multiple variable model (data not shown).

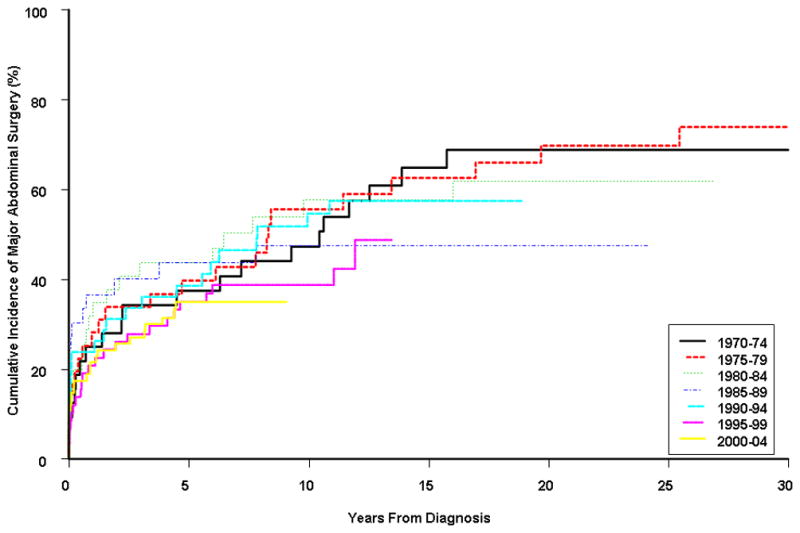

Changes in Major Abdominal Surgery Rates

The study population was divided into seven groups by year of diagnosis: 1970–74, 1975–79, 1980–84, 1985–89, 1990–94, 1995–99, and 2000–04. The 5-year cumulative probability of first major abdominal surgery ranged from 35.1% (95% CI, 22.8%–45.9%) in patients diagnosed in 2000–04 to 43.7% (24.3%–58.8%) in those diagnosed between 1980 and 1984 (Figure 2). The 20-year cumulative incidence of surgery ranged from 47.4% (26.4%–65.2%) in the 1985–89 cohort to 69.7% (48.2%–82.3%) in the 1975–79 group. A more detailed summary of cumulative risk of major abdominal surgery by calendar period of diagnosis can be found in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Table 3). The median time to first major abdominal surgery varied from 6.4 years in the 1980–84 group to >12 years in the 1995–99 group (Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative probability of major abdominal surgery stratified by time period of diagnosis. Using the period 1970–74 as a reference, there was no significant association between time to first major abdominal surgery with calendar period: 1970–74 versus 1975–79 (p=0.78), 1980–84 (p=0.97), 1985–89 (p=0.52), 1990–94 (p=0.81), 1995–99 (p=0.22), and 2000–04 (p=0.22).

A separate proportional hazards model using the total cohort (n=310) to assess the association with calendar period (using the period 1970–74 as a reference) indicated the cumulative risk of a first major abdominal surgery remained stable over the past four decades (p=0.60). Including age, gender, and early presence of extraintestinal manifestations did not qualitatively change this result (Supplementary Table 4). Similarly, when considering the number of major abdominal surgeries per year (per patient) instead of time to initial major abdominal surgery, no significant association of calendar period with surgery rates was observed, p=0.51 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of the number of major abdominal surgeries per patient-year by calendar period of observation in the entire Olmsted County Crohn’s disease cohort diagnosed between 1970 and 2004, and followed through 2009 (n=310).

| Number of Major Surgeries per 5 years | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Observation period | Number of diagnosed cases | 1st 5 years post- diagnosis | Post-5 years from diagnosis |

| 1970–74 | 32 | 0.74 | -- |

| 1975–79 | 36 | 0.87 | 0.36 |

| 1980–84 | 35 | 0.74 | 0.42 |

| 1985–89 | 33 | 0.83 | 0.54 |

| 1990–94 | 42 | 1.14 | 0.36 |

| 1995–99 | 58 | 0.82 | 0.39 |

| 2000–04 | 74 | 0.70 | 0.48 |

| 2005–09 | -- | 0.58 | 0.21 |

Assessment of rates of major abdominal surgery was assessed using a generalized linear regression model (assuming a negative binomial distribution for surgeries). Gender (p=0.20) and year (p=0.28) were not significant. The rate of surgery in the first 5 years post-diagnosis was significantly higher than in subsequent years of the clinical course (p<0.001).

Bowel Resection and Ileal/Ileocolonic Resection

Similar trends were observed for bowel resection and ileal/ileocolonic resection. These results are available as supplemental material.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study investigating the incidence of and risk factors for surgery as well as changes in surgery rates over time in a United States population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease.

In Olmsted County, the earliest report indicated that 41% of patients with Crohn’s disease diagnosed between 1935 and 1975 underwent at least one disease-related abdominal surgical procedure after a median follow-up of 8.5 years since the diagnosis17. Herein, the cumulative probability of first major abdominal surgery from time of diagnosis was 38.2%, and 47.6% at 5 and 10 years, respectively. When comparing our update with the previous report from the same cohort, the risk of a surgical procedure remained broadly stable over time, with approximately half patients having required resection by year 10. This was confirmed by the analysis of changes in surgical rates over the past decades. Using the period 1970–74 as a reference, the cumulative risk of having major abdominal surgery or bowel resection remained stable over the past four decades. Similar figures were observed when considering the number of surgical procedures per year instead of the cumulative probability of surgery.

Recently, several population-based studies specifically addressed the issue of surgical time trends in Crohn’s disease3, 9, 10. In a population-based cohort of patients diagnosed in Cardiff, Wales from 1986 to 2003, 5-year resection rates for Crohn’s disease fell signi cantly, from 59% (1986–91) to 25% (1998–2003)10. In the Canadian province of Manitoba, patients diagnosed between 1996 and 2000 were 28% less likely to require surgery, and those diagnosed after 2001 were 43% less likely to require surgery, compared to a baseline cohort of patients diagnosed before 19963. By contrast, in Olmsted County, the cumulative probability of first major abdominal surgery from time of diagnosis remained stable over time, being 35.1% (1999–2004) and 37.1% (1970–74) at 5 years. Our findings are in line with a recent report that used the U.S. Nationwide Inpatient Sample to identify all hospital admissions for Crohn’s disease for each year from 1993 through 200410. From 1993 to 2004, the rates of total colorectal resections and small bowel resections had not declined10. Admittedly, this study is more difficult to interpret because total surgical hospitalizations nationwide are affected not only by surgical rates but also by incidence rates. In other words, a decreasing surgical rate among Crohn’s disease patients could be offset by an increasing incidence of Crohn’s disease to produce a seemingly stable total number of surgical hospitalizations.

The main difference between Olmsted County and Cardiff is the fact that the need for surgery was much lower in the 1980s in the U.S. than in Wales9 (43.7% versus 59% at 5 years, respectively). The cumulative probability of having major abdominal surgery was even lower for patients diagnosed between 1970 and 1974 (37.5% at 5 years) than for those diagnosed about 10 years later in Olmsted County. The reasons for such a discrepancy remain unknown. Other yet to be identified environmental or genetic factors unique to geographical differences could explain, at least in part, the disparity in surgery rates observed between North-American and European studies. Indeed, it is unlikely that differences in diagnostic and therapeutic modalities explain such disparity between two developed countries.

One of the strengths of our study resides in the fact that this is a population-based study linked to the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which allows accessibility to all medical records of patients diagnosed with Crohn’s disease. This provides complete medical follow-up for county residents. Indeed, the median follow-up per patient was 12.0 years. Limitations of this study include the fact this is a retrospective medical-records based study; thus, information not recorded in the medical records would be missed. The main limitation to our study is that it did not evaluate the impact of modifiable factors such as on-going medical therapies.

In Norway, 9% of patients with Crohn’s disease required 2 or more operations after a 10-year follow-up5. Similarly, in Denmark, with a median follow-up of 8.5 years, 14% of patients were operated on two times and 3% had 3 or more operations4. In Olmsted County, we found that 65 (21%) and 32 (10%) patients, respectively, underwent at least 2 or 3 abdominal major surgeries during a median follow-up of 12 years. Importantly, the cumulative probability of second major abdominal surgery among patients who had first major abdominal surgery was high, reaching 44.9% at 10 years.

The indications for surgery were only assessed in Olmsted County (1935–75) and in Stockholm County (1955–94)11, 17, and had never been investigated in the era of biologics and widespread use of immunomodulators. In Olmsted County, twenty-one percent of those who required operation presented emergently with an acute abdomen17. The indications for surgery were intractable pain in 79%, obstruction in 33%, bleeding in 36%, diarrhea in 64%, and fistula in 17%17. By updating Olmsted County data, the main indications for surgery were obstruction or medical therapy failure in 24% of cases, indicating that intractability to medical treatment requiring surgery remains frequent in Crohn’s disease.

The type of surgery performed for Crohn’s disease was evaluated in three population-based cohorts9, 17, 18. In Olmsted County (1935–75), resection of the colon and/or small bowel was the surgical procedure in approximately two-thirds of operations, 10% had a total proctocolectomy, and surgery was considered “palliative” in approximately one-third of operations17. In Cardiff (1986–2003), in agreement with our findings, ileocecal resection was the main indication for surgery and was performed in 67% of patients9. Stricturoplasty was performed in 7% of patients in Cardiff and was the second main indication for surgery9, whereas in this cohort, only one out of 310 patients underwent stricturoplasty. This may reflect differences in surgical management of small bowel strictures. The first abdominal surgery was a total proctocolectomy in 10.5% patients in Olmsted County in patients diagnosed between 1970 and 2004. This rate is higher than in Cardiff, where only 5% of patients had this surgical procedure9, but is similar to that observed in the same population-based cohort in patients diagnosed between 1935 and 197517, indicating that this surgical procedure is still required in a significant number of patients. A subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis or a diverting procedure was performed in 6% of patients in Olmsted County (1970–2004). Overall, these figures are broadly similar to those observed in Cardiff (1986–2003)9 and in a previous report from Olmsted County (1935–75)17, indicating that no changes occurred in indications for surgery in Crohn’s disease over the past decades. It is noteworthy that the first major abdominal surgery using a laparoscopic approach was performed on December 2007 and was an ileocecal resection. Until March 2009, 16% patients benefited from laparoscopic surgery. This is the first population-based study providing this information.

Risk factors for having surgery have been investigated in three population-based cohorts5, 9, 11. Ileal disease and in some studies ileocolonic disease, orojejunal disease, oral corticosteroid therapy within 3 months of diagnosis, early use of thiopurines within the first year of diagnosis, age younger than 40 years or older than 30 years, as well as structuring or penetrating disease behavior, were identified as independent factors for having surgery in Crohn’s disease5, 9, 11. In Olmsted County, multivariate analysis confirmed that patients with ileocolonic, small bowel and upper gastrointestinal disease have a 3- to 4-fold increased risk of major abdominal surgery compared with colonic disease. Only one population-based study assessed the influence of smoking habits on the need for surgery5. In sharp contrast to available literature data, smoking status did not influence the risk of surgery significantly5. The data from Olmsted County are thus the first to confirm the well-established deleterious effect of active smoking on the course of Crohn’s disease in a well-defined population-based cohort. Gender was not associated with the need for surgery in most available population-based cohorts5, 9, 11. In Olmsted County, male gender was slightly but significantly associated with the risk for surgery. Further studies should confirm if male gender is an independent risk factor for Crohn’s disease. Penetrating disease behavior at diagnosis was associated with a higher risk for surgery.

The results regarding medication use and surgery risk must be interpreted carefully. Observational studies are subject to bias by indication (i.e., patients with more severe forms of disease are not only more likely to receive a medical intervention but are also more likely to develop natural history endpoints that are related to disease severity). The seemingly “protective” effect of 5-aminosalicylates on the risk of surgery most likely arises from the fact that such medications are more likely to be prescribed to patients with milder forms of Crohn’s disease, and that patients with milder Crohn’s disease are less likely to require surgery.

In conclusion, the cumulative risk of major abdominal surgery in this population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease exceeded 60% after 30 years of disease, and many patients required second or third surgeries. No changes in surgical rates were observed over the past four decades. Non-colonic disease extent, current cigarette smoking, male gender, penetrating disease behavior, and early need for corticosteroids were significantly associated with need for major abdominal surgery. A better knowledge of the natural history of Crohn’s disease in the era of biologics together with the identification of risk factors for surgery may be used in future disease-modification trials.

Supplementary Material

STUDY HIGHLIGHTS.

What is current knowledge

In some population-based studies, the cumulative incidence of surgical resection in Crohn’s disease is as high as 80% after 20 years of disease.

Studies examining temporal trends of surgical rates in Crohn’s disease have revealed conflicting results.

Relatively few studies have examined which clinical and demographic features are associated with risk of surgery in Crohn’s disease.

What is new here

In this population-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota, the cumulative risk of major abdominal surgery was 38% at 5 years, 48% at 10 years, and 58% at 20 years after diagnosis.

Patients with ileocolonic, isolated small bowel, or upper gastrointestinal involvement were 3 to 4 times more likely to require major abdominal surgery relative to patients with colonic disease alone.

Males, current smokers, patients with penetrating disease behavior at diagnosis, and patients with early need for corticosteroids were also more likely to require surgery.

In contrast to some studies, major abdominal surgical rates remained stable over the course of the study period.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Supported in part by Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; and made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant number R01 AG034676 from the National Institutes on Aging).

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 111th Annual Meeting of the American Gastroenterological Association, New Orleans, Louisiana, May 1–6, 2010 (Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Cumulative incidence of and risk factors for major abdominal surgery in a population-based cohort of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138(5 Suppl 1):S1184.)

Conflicts of interest: No relevant conflicts of interest for any authors.

Author contributions:

Study concept/design: Peyrin-Biroulet, Loftus

Data acquisition: Peyrin-Biroulet, Loftus

Data analysis/interpretation: Peyrin-Biroulet, Harmsen, Zinsmeister, Loftus

Drafting manuscript: Peyrin-Biroulet

Critical revision of manuscript: Harmsen, Tremaine, Zinsmeister, Sandborn, Loftus

Statistical analysis: Harmsen, Zinsemeister

Funding: Sandborn, Loftus

Supervision: Loftus

References

- 1.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of adult Crohn’s disease in population-based cohorts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:289–97. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bougen G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Surgery for Adult Crohn’s Disease: What is the Actual Risk? Gut. 2011;60:1178–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.234617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen GC, Nugent Z, Shaw S, Bernstein CN. Outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease improved from 1988 to 2008 and were associated with increased specialist care. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:90–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munkholm P, Langholz E, Davidsen M, Binder V. Intestinal cancer risk and mortality in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1716–23. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91068-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Hoie O, Stray N, Sauar J, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Lygren I. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramadas AV, Gunesh S, Thomas GA, Williams GT, Hawthorne AB. Natural history of Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort from Cardiff (1986–2003): a study of changes in medical treatment and surgical resection rates. Gut. 2010;59:1200–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, Knudsen E, Pedersen N, Elkjaer M, Bak Andersen I, Wewer V, Norregaard P, Moesgaard F, Bendtsen F, Munkholm P. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003–2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ljung T, Karlen P, Schmidt D, Hellstrom PM, Lapidus A, Janczewska I, Sjoqvist U, Lofberg R. Infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical outcome in a population based cohort from Stockholm County. Gut. 2004;53:849–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.018515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramadas AV, Gunesh S, Thomas GA, Williams GT, Hawthorne AB. Natural history of Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort from Cardiff (1986–2003): a study of changes in medical treatment and surgical resection rates. Gut. 2010;59:1200–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.202101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones DW, Finlayson SR. Trends in surgery for Crohn’s disease in the era of infliximab. Ann Surg. 2010;252:307–12. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e61df5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernell O, Lapidus A, Hellers G. Risk factors for surgery and postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Ann Surg. 2000;231:38–45. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loftus EV, Jr, Silverstein MD, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–1993: incidence, prevalence, and survival. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1161–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Tremaine WJ, Melton LJ, 3rd, Sandborn WJ. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:254–61. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55:749–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrez MV, Valente RM, Pierce W, Melton LJ, 3rd, van Heerden JA, Beart RW., Jr Surgical history of Crohn’s disease in a well-defined population. Mayo Clin Proc. 1982;57:747–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellers G. Crohn’s disease in Stockholm county 1955–1974. A study of epidemiology, results of surgical treatment and long-term prognosis. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1979;490:1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.