Abstract

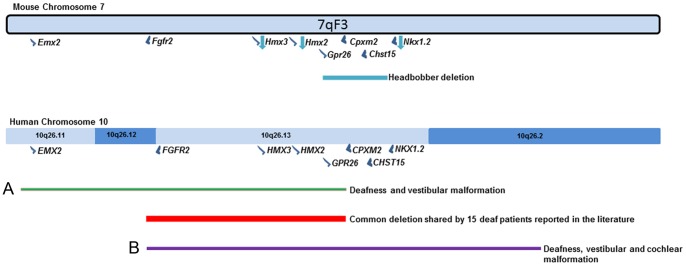

The recessive mouse mutant headbobber (hb) displays the characteristic behavioural traits associated with vestibular defects including headbobbing, circling and deafness. This mutation was caused by the insertion of a transgene into distal chromosome 7 affecting expression of native genes. We show that the inner ear of hb/hb mutants lacks semicircular canals and cristae, and the saccule and utricle are fused together in a single utriculosaccular sac. Moreover, we detect severe abnormalities of the cochlear sensory hair cells, the stria vascularis looks severely disorganised, Reissner's membrane is collapsed and no endocochlear potential is detected. Myo7a and Kcnj10 expression analysis show a lack of the melanocyte-like intermediate cells in hb/hb stria vascularis, which can explain the absence of endocochlear potential. We use Trp2 as a marker of melanoblasts migrating from the neural crest at E12.5 and show that they do not interdigitate into the developing strial epithelium, associated with abnormal persistence of the basal lamina in the hb/hb cochlea. We perform array CGH, deep sequencing as well as an extensive expression analysis of candidate genes in the headbobber region of hb/hb and littermate controls, and conclude that the headbobber phenotype is caused by: 1) effect of a 648 kb deletion on distal Chr7, resulting in the loss of three protein coding genes (Gpr26, Cpmx2 and Chst15) with expression in the inner ear but unknown function; and 2) indirect, long range effect of the deletion on the expression of neighboring genes on Chr7, associated with downregulation of Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 homeobox transcription factors. Interestingly, deletions of the orthologous region in humans, affecting the same genes, have been reported in nineteen patients with common features including sensorineural hearing loss and vestibular problems. Therefore, we propose that headbobber is a useful model to gain insight into the mechanisms underlying deafness in human 10qter deletion syndrome.

Introduction

Numerous mouse mutants with hearing defects and vestibular problems are available as models for understanding human deafness, many of them arising from different mutagenesis programs [1], [2]. More than 300 human syndromes with the presence of deafness and/or vestibular malfunction due to abnormal inner ear development have been described to date [3], and still a lot of work needs to be done in order to identify the causative genes for a number of these pathologic conditions.

Here we describe headbobber (hb), a recessive mouse mutant created by insertional mutagenesis in a transgenic line carrying a 8 kb plasmid phβAPr-1neo, which includes a portion of the human beta actin promoter [4]. Approximately 2 weeks after birth, the headbobber homozygous mutants start to show abnormal hyperactivity and circling movements which are typical of balance defects [5]. Moreover, they are completely deaf. The main features of the hb/hb inner ear phenotype include strial abnormalities with lack of intermediate cells, lack of interdigitations between marginal and basal cells and collapse of Reissner's membrane, which is sufficient to explain the absence of endocochlear potential [6]–[8]. The hb/hb vestibular system shows severe morphological defects, with lack of semicircular canals and cristae together with the formation of a characteristic fused utriculo-saccular compartment hosting a fused macula. We have been able to localise the headbobber mutation to an 8 Mb region on the distal portion of mouse chromosome 7 on an intraspecific backcross ([hb/hb X CBA] F1 X hb/hb). The transgene was mapped to the same region of chromosome 7, 65 cM from the centromere between the markers D7Mit105 and D7Mit12, on a reciprocal backcross ([hb/hb X CBA] F1 X CBA). We have used microarray Comparative Genomic Hybridization [9] and whole genome sequencing to narrow down the headbobber region, and found a 648 kb homozygous deletion in the distal part of mouse chromosome 7F3 500 kb telomeric to the Hmx3 and Hmx2 locus [10]. We have previously reported in published abstracts the head bobbing and circling behavior, deafness, failure in semicircular canal formation, mapping of the phenotype and the transgene to chromosome 7 by linkage analysis, and non-complementation with Hmx3 [11]–[13] and present the full dataset here. While this manuscript was in the final stages of preparation, a paper describing the same mutation and general phenotype in the headbobber mouse was published [4], where the authors utilise molecular, histological, electrophysiological and genomic tools to characterize the headbobber inner ear phenotype, identify the mutation and map the transgene integration site.

In this work, we propose a mechanism to explain both the hearing and vestibular phenotypes shown by the headbobber mutant and link it to the expression pattern in the inner ear of the three deleted genes (Gpr26, Cpxm2 and Chst15). Interestingly, we report that different-sized deletions in the homologous region in humans have been reported in fifty-nine patients affected by the so-called 10qter syndrome [14]–[18]. These patients display a wide clinical variability of features which include sensorineural deafness and vestibular defects in nineteen cases [18]. Therefore, we propose that headbobber is a useful model to gain insight into the mechanisms underlying human 10qter deletions and to identify the candidate genes for this disease.

Furthermore, we use the headbobber mouse model to investigate the overlapping role of the homeobox transcription factors Hmx2, Hmx3 and Nkx1-2 in inner ear development and to gain more insights on their transcriptional regulation [19].

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All mouse breeding and investigation were carried out with authorization of the UK Home Office project license. All mice were killed by cervical dislocation and decapitation, all surgeries were performed under anesthesia with urethane (2 mg/kg). All efforts were made to minimize suffering.

Mouse mutants

Headbobber was created by transgenic insertion arising in a transgenic line carrying a 8 kb plasmid phβAPr-1neo, which includes a portion of the human beta actin promoter [4], [20]. Mice carrying the headbobber mutation were originally obtained from Paul Overbeek at the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas. Details of the genetic background were unknown, but the mutants were maintained within a closed colony and heterozygote or wildtype littermates were used as controls. The Hmx3KO mice were described in [20], (MGI name: Hmx3tm1Ebo). All mouse breeding and investigation were carried out with authorization of the UK Home Office.

Phenotyping and behavioural analysis

A brief 20 kHz soundburst at the intensity of 90–100 dB was generated by a custom-made click box. A flick backwards of the pinna upon hearing the sound was counted as a positive Preyer response. Other behavioral testing (air righting, contact righting, Elevated Platform, Negative Geotaxis and reaching and swimming behavioral tests) were performed as described previously [11].

Genetic mapping

Intraspecific backcrosses were generated by crossing head bobber mice with the inbred strain CBA/Ca. To map the mutation, the following backcross was used (hb/hb X CBA/Ca)F1 X hb/hb. Genomic DNA was examined using PCR primers flanking microsatellite regions. A subset of 34 of the backcross mice were used for a genome scan (data not shown). Only 11% recombination was found between the headbobber phenotype and D7Mit9. The rest of the backcross mice were typed for this marker and 7 other chromosome 7 markers (Figure S1). The headbobber mutation cosegregated with D7Mit241 and D7Mit71 and was proximal to D7Mit12 and distal to D7Mit103 and D7Mit105. To map the transgene, the backcross (hb/hb X CBA/Ca)F1 X CBA/Ca was used. To determine the presence or absence of the transgene, primers to the neomycin resistance component were used. The mice generated to map the transgene were analysed for the markers D7Mit105 and D7Mit12 and typed for the presence or absence of the transgene.

Genotyping and Neo counting

srPCR was run to confirm the absence/presence of Neo and absence/presence of a region deleted in the hb mutant. Primers used were Neo F (CAAGATGGATTGCACGCAGGTTCTC), Neo R (GACGAGATCCTCGCCGTCGGGCATGCGCGCC), hb F (CACAACGTCGATGAGTTATTTAG) hb R (ACTATCACAACCACCAGCAGC).

Neo F and Neo R produced a product approximately 550 bp, hb F and hb R produced an approximately 120 bp product. Presence of hb and absence of Neo indicated a wildtype, absence of hb and presence of Neo indicated a homozygous mutant, and presence of both indicated a heterozygote.

qPCR was run to calculate number of copies of Neo, and thus the transgene, present in the hb mice. This was done using the standard Sanger Institute protocol, details of which can be found at http://www.knockoutmouse.org/kb/entry/91/. Accessed 2012 Aug 2.

Complementation test

hb/hb mice on the original genetic background were crossed with mice heterozygous for the Hmx3KO [20]. The presence of the knockout allele was typed by Southern blotting using a 1090 bp EcoRI/StuI fragment of the Hmx3 cDNA. The hb allele generated a band of 9070 bp and the knockout allele generated a band of 4911 bp. The offspring (Hmx3KO/hb N = 12, +/hb N = 9) were tested for the Preyer reflex, the swimming test, the reaching response, the air righting response, the contact righting response, the elevated platform test, negative geotaxis and compared with the Hmx3 knockout mice (Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO N = 7, +/Hmx3KO N = 5).

Endocochlear Potential measurements

Endocochlear potential from hb/hb, +/hb, Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO, +/Hmx3KO, Hmx3KO;hb and wildtype mice aged 60 to 82 days were measured as previously described [21]. Sex and coat colour show no relationship to the auditory phenotype.

Compound Action Potentials measurements

Mice were anesthetized with urethane (2 mg/kg), a tracheal cannula was inserted, and the mouse was placed on a heated blanket. The middle ear was opened leaving ossicles intact and a teflon-coated silver wire was placed on the round window of the cochlea. Stimuli were presented via a closed, calibrated sound system and consisted of tone pips of 15 msec duration, 1 msec rise/fall time. Responses to 200 stimuli were averaged and used to determine the threshold, defined as the lowest intensity to produce a recognizable waveform using either 5 dB or 2 dB intensity steps for each frequency tested [22].

Paintfilling

Nine littermates at postnatal day 1 (three +/+ controls, three +/hb and three hb/hb) were fixed in Bodian's Fixative for 60–120 min at 4°C in a rotator. The half heads were processed and filled as previously described [23]. Ears were viewed with a Leica MZ16 light microscope and images were acquired by the Leica DFC490 camera.

Scanning Electron Microscopy

A total of 10 mice aged P5 (3 hb/hb 4 +/hb and 3 +/+) were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using the OTOTO method, as previously described [24], and viewed with a Hitachi FE S-4800 Scanning Electron Microscope operated at 3–5 kV.

3D Reconstruction

Serial inner ear sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin from newborn +/hb, hb/hb and hb/Hmx3KO mice were captured using a HV C20 CCD camera and imported into a frame grabber programme. Areas of interest on each section were then selected using a customised version of Image Pro. These selected areas were saved as tif files and Spyglass Slicer then rendered these as a solid 3D object.

Transmission electron microscopy

Inner ears from fourteen-month-old hb/hb and +/hb littermates were fixed in glutaraldehyde, decalcified in 4%EDTA, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide and saturated in uranyl acetate. Then the samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series and embedded in propylene oxide and Araldite resin (1∶1) and 3∶1 resin for 30 min and Araldite resin overnight under vacuum. The samples were embedded in fresh Araldite resin at 60 degree for 24–48 hours. Thin sections were taken from selected regions and examined using a Philips EM300 or 410 transmission electron microscope [25].

In situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry

For the marker analysis on sections, 3 embryos of each genotype were used and for whole mount in situ hybrisation 4 embryos of each genotype were used. For whole mount in situ hybridisation, embryos were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and processed as described [26]. For in situ hybridisation and immunohistochemistry on sections, samples were fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into 8 µm sections and the Ventana Discovery system (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc Illkirch, France) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmids containing cDNA of Bmp4 (Jones et al., 1991), and antibodies against Sox2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat. no. ab15830), Calretinin (Chemicon international, Millipore, Hampshire, UK, cat. no. AB5054), Myo7A (Proteus Bioscience, Ramona, CA, cat.no. 25-6790), P27kip1 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danversm cat. No. 711-065-152), Trp2 (Abcam, Cambridge, uk, cat.no ab74073), Laminin (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab11575), c-kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat. no. ab5506), Kcnj10 (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel, cat.no. APC-035), Hmx2 (Chemicon international, Millipore, Hampshire, UK, cat. no. AB5746), Hmx3 (Chemicon international, Millipore, Hampshire, UK, cat. no. AB5744), Nkx1.2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK ab105940), Fgfr2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab10648), Chst15 (LifeSpan BioSciences, Seattle, WA, US, cat.no.LS-C82503/31418), Gpr26 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab101606), Cpxm2 (Sigma-Aldrich. St.Louis, MO, US, cat.no. WH0119587M1) and Mast Cell Tryptase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab2378) were used. Secondary antibodies were Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA) biotin conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (711-065-152), Jackson ImmunoResearch biotin conjugated donkey anti-goat (705-065-147) and Epitomics (Burlingame, CA, USA) anti-mouse IgG (3021-1).

Probes for the murine Hmx2 (ENSMUSG00000050100) and Hmx3 (ENSMUSG00000040148) genes were obtained by PCR on cDNA obtained from C57BL/6 embryos at E14.5 using specific primers designed with 3′ T7 promoter and 5′ T3 promoter tails. PCR primers were designed with the help of Primer3 (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm. Accessed 2012 Aug 2.) and ordered from Sigma-Aldrich. They amplify a 200 bp conserved region which is upstream of the homeobox region (within the second exon) in both genes.

FHmx3_T3: 5′ AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAG-CCTCTGCTCAAGGCTGACC-3′

RHmx3_T7: 5′ AATACGACTCACTATAGGGAG-GGCTTCTTCTCGGGACTCTC-3′

FHmx2_T3: 5′- AATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAGACGCCATTCCTTTCTCCTTC-3′

RHmx2_T7: 5′ AATACGACTCACTATAGGGAG-GACTCGAGCTGGTACACTTGG-3′

Digoxygenin-labelled RNA probes were generated by in vitro transcription using T3 and T7 RNA polymerases as described in [26].

Slides were photographed using a microscope with Nomarski optics (Axioplan; Zeiss) and digital camera (AxioCam; Zeiss). Images were acquired by the AxioCam MRc camera (Carl Zeiss), using the Axiovision 3.0 software (Carl Zeiss), with a format of 1030 _ 1300 pixels. Pictures were processed with Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Whole mount immunofluorescence

Three pairs of littermates at postnatal day 4 (three +/hb controls, and three hb/hb, from three different litters), were fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) for 2 h at room temperature. Sensory tissue was dissected in PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min and blocked overnight at 4°C with 4% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Tissues were then incubated with primary antibody anti Chst15 (Sigma Aldrich, UK, cat. num. HPA017584, 1∶300 dilution) for 2 h, rinsed with PBS, stained with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) for 1 h, counterstained with Alexa Fluor 594 phalloidin (0.001 U µl−1; Molecular Probes) and mounted using Prolong Antifade (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence confocal images were obtained with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope with a 63×1.4 numerical aperture objective.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

The heads of E12.5 embryos and the inner ears of P5 pups were dissected and stored at −20°C in RNAlater stabilization reagent (QIAgen, cat. no. 76106). RNA was extracted using QIAshredder columns (QIAgen, cat. no. 79654) and the RNeasy mini kit (QIAgen, cat. no. 74104), following the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR was carried out on cDNA from the above tissue, using TaqMan probes and reagents from Applied Biosystems as already described in [27]. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by the Student's t test.

Western blot analysis

Protein levels from 2 inner ears pooled together for each genotype were analyzed by Western blot as follows. Inner ear samples from each mouse at postnatal day five were homogenized using micropestles (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) and lysed on ice in 400 µl ice-cold 50 nmol/L Tris.HCl, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 5 mmol/L EGTA, pH 7.5, 0.5% NP-40, with Roche Complete Mini protein inhibitors (cat.no. 11836153001). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. Insoluble material was removed from the protein extracts by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The protein content in supernatant fractions was quantified (Nanodrop ND-8000, A280 assay) and aliquots were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until use. 200 µg of inner ear protein extracts from hb/hb and control littermates were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with anti-mast cell tryptase antibody. GAPDH was used as loading control. Protein blots were probed for 2–4 h at room temperature with specific antibodies, followed by horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody, and analyzed using an ECL chemiluminescence system (Thermo Fisher Scientific UK, cat.no.34077). The antibodies (Abs) used were Mast Cell Tryptase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab2378; 1∶1000) and Gapdh (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, cat.no ab9482; 1∶5000).

Array CGH analysis using Agilent mouse genome 244A CGH microarrays

4 hb/hb mutants and 4 +/+ controls aged from P1 and P30 were used for the aCGH. Genomic DNA was labeled using the BioPrime DNA Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, 18094-011). 450 ng of each experimental sample and reference were mixed with 60 µl of 2.5X random primer solution (Invitrogen) and nuclease-free water (Ambion, AM9937) to a final volume of 130.5 µl. Samples were denatured at 100°C for 10 min before being immediately cooled on ice. After addition of 15 µl of 10X dNTP mix (2 mM dATP, 2 mM dGTP, 2 mM dTTP, 1 mM dCTP), 1.5 µl of 1 mM Cy5-dCTP (experimental sample) or Cy3-dCTP (reference sample) (GE Healthcare, PA55321) and 3.0 ul of Klenow Fragment (40 U/µl) (Invitrogen), samples were incubated at 37°C for 16 h (overnight). Samples were purified using the PureLink PCR Purification Kit following the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, K3100-01). Labeling efficiency was assessed using the Nanodrop-8000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Samples were hybridised to Agilent 244A mouse genome arrays following the manufacturer's protocol (G4410-90010). Microarrays were scanned using the Agilent DNA High Resolution Microarray Scanner (Agilent, G2505C) following the manufacturer's protocol. Raw image data was processed using Agilent's Feature Extraction software (v10.7.3.1). Bioconductor packages limma, DNAcopy and CNTools were used to analyse copy number variations [28]. Additionally, plots focusing on these regions were produced for visual confirmation using the “whole” option of “R”.

Whole genome sequencing and sequence analysis of the headbobber mutation

Two hb/hb were used for whole genome sequencing. Sequencing was performed using Illumina Genome Analyzer II platform as paired-ends 100-bp reads according to the manufacturer's protocol. Four lanes of sequence were generated for each mouse. Sequences were mapped to the reference genome (NCBIm37) using bwa0.5.9 [29] and were improved by local realignment around insertions and deletions discovered in the mouse genomes project [30] using GATK 1.1–5 [31]. The lanes were merged and library duplicate fragments were marked using picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net, version 1.47. Accessed 2012 Aug 2.) and the merged BAM files were analysed using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software [32]. Sequence data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (accession number: ERP000977).

Results

The headbobber inner ear phenotype

The mouse mutant headbobber (hb, MGI:2447989) harbours a recessive mutation that causes deafness, and vestibular dysfunction that is manifested as circling, hyperactivity and head bobbing. The headbobber mutation arose by transgenic insertion in a line carrying a plasmid phβAPr-1neo, which includes a portion of the human beta actin promoter [4]. Only homozygotes are affected suggesting recessive inactivation of one or more genes. hb/hb showed abnormal response to the air righting, contact righting, Elevated Platform, Negative Geotaxis and reaching and swimming behavioural tests (data not shown). Moreover, they do not show any Preyer reflex in response to sound.

Consistent with its early onset strong vestibular phenotype, hb/hb mutants display a gross vestibular dysmorphology (Fig. 1B). hb/hb mutants show a cyst-like vestibular system, with no clear evidence of semicircular canals. 3D reconstruction of paraffin wax inner ear serial sections from newborns show the presence of an abnormal endolymphatic duct in hb/hb (Figure S2 G–H). The cochlea, however, has a normal gross morphology compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1 A–B).

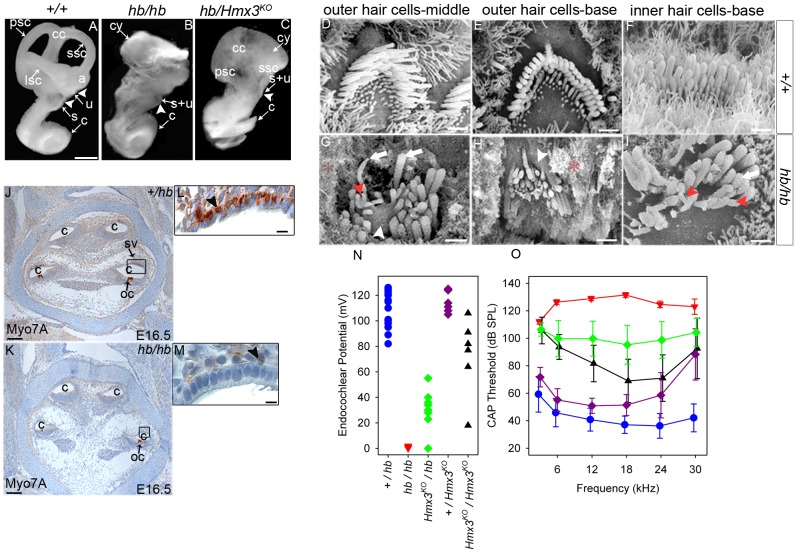

Figure 1. Overview of the headbobber inner ear phenotype.

A–C: Headbobber inner ear gross morphology analysed by paintfilling of newborn hb/hb, hb/Hmx3KO and control littermates, clearly showing the gross malformation of the semicircular canals (cy) observed in hb/hb and hb/Hmx3KO. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. D–I: SEM of organ of Corti of hb/hb and control littermates at P5. In the basal and middle turns of the cochlea, hair bundles in hb/hb look severely disorganized if compared with the one displayed by the littermate controls, showing bifurcations (red arrowheads in G and I) and fusion of stereocilia (white arrowheads in G and H). Height and thickness of stereocilia are affected too in hb/hb mutants (white arrows). *: debris from collapse of Reissner's membrane. Scale bar:1.5 µm. J–M: Myo7A expression in hb/hb mutants and control littermates at E16.5. Myo7A marks melanoblasts in stria vascularis and we did not detect any melanoblasts in the hb/hb developing stria vascularis when compared to littermate controls (arrowheads in L,M). Scale bars: J,K: 200 µm; L,M: 5 µm. N–O: Endocochlear Potential (N) and Compound Action Potential (O) measurements on a total of fifteen hb/hb (red triangles), seventeen +/hb (blue circles), six Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO (black triangles), eight HmxKO/hb (green diamonds) and and eight +/Hmx3KO (purple diamonds), all aged 60 to 102 days. Individual EP measurements are plotted in N, and means +/− SD are plotted for compound action potential thresholds except for hb/hb (red triangles) where there were no responses, so the maximum sound level used is plotted (if hb/hb had any response, thresholds would be above this level). a: ampulla, bc: basal cell, bv: blood vessel, c:cochlea, cc:common crus, cy: vestibular cyst, ed: endolymphatic duct, ic: intermediate cell, int: interdigitation, lsc:lateral semicircular canal, mc: marginal cell, oc:organ of Corti, psc: posterior semicircular canal, rm: Reissner's membrane, s: saccule, ssc: superior semicircular canal, s+u: utriculosaccular space, sv: stria vascularis, u: utricle.

hb/hb mice are profoundly deaf as demonstrated by the absence of any compound action potential responses (Fig. 1O). Endocochlear potentials are around zero, compared to the normal levels of 80–120 mV (Fig. 1N). Scanning electron microscopy of the organ of Corti revealed that in hb/hb, both inner and outer hair bundles look severely disorganized and are arranged in randomly positioned clumps rather than in the normal‘V’-shaped pattern (Fig. 1D). In detail, hair cells in the basal and middle turn contain elongated stereocilia often fused at the stereocilia base (white arrowheads in Fig. 1 G,H) and showing bifurcations (red arrowheads in Fig. 1G,I). Stereocilia polarity, thickness and height seem to be affected in hb/hb when compared to their littermate controls (arrows in Fig. 1 G,I), with membranes looking in a state of collapse in mutants. (* in Fig. 1G,H).

We have used Myo7A to detect the presence of neural crest-derived melanoblasts (precursors of intermediate cells) in developing stria at E16.5, and we do not detect melanoblasts in the hb/hb developing stria compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1J–M). Later in development, as shown in Figure S3, the stria vascularis looks severely disorganized in hb/hb adult mutants compared to littermate controls, lacking the usual extensive cellular interdigitation. No intermediate cells are detected in hb/hb stria and Reissner's membrane is collapsed.

Functional and anatomical studies of the mouse and human inner ear have identified the same broad categories of pathology in the two species: morphogenetic, cochleo-saccular and neuroepithelial [33]. Morphogenetic abnormalities involve gross structural deformities of the labyrinth. A strial abnormality is the primary cochleo-saccular defect in which there is a reduced or absent endocochlear potential (EP) and sometimes collapse of Reissner's membrane, which eventually results in degeneration of the organ of Corti. Neuroepithelial defects originate in the organ of Corti and do not affect the stria vascularis directly [34]. Taken together, our results allow us to consider headbobber as a combined morphogenetic and cochleo-saccular mutant and identification of the genes affected by the mutation will provide important information on the biological basis of normal hearing and vestibular system development.

The headbobber mutation

The headbobber mutation and the transgenic insertion have been independently mapped to the same region of chromosome 7, 65 cM from the centromere between the markers D7Mit105 and D7Mit12, using two separate backcrosses (Figure S1 AB). The headbobber region is 8 Mb and contains 86 annotated genes.

In order to narrow down the headbobber region and define the physical effect of the transgenic insertion on Chr7, we performed array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) on four hb/hb mice to compare to wild type controls as well as whole genome sequencing on two mutants. In detail, aCGH is a highly useful tool to define DNA copy number variations (either deletions or duplications), and therefore identify zones of aberrations in the genome [28]. Consistent with the results we got from the genetic mapping, our aCGH and deep sequencing data detect a ∼ 648 kb deletion on Chr7 in all the mutant samples (Chr7: 139061190–139708657; Fig. 2A,B), which maps 375 kb telomeric to the Hmx3 locus and 78 kb centromeric to Nkx1.2. We also detected an insertion from mouse chromosome X at the end of the deletion (Chr7:139708658–139709168). The inserted sequences correspond to the genomic region ChrX: 159137545–159137781 and no genes are annotated in this region.

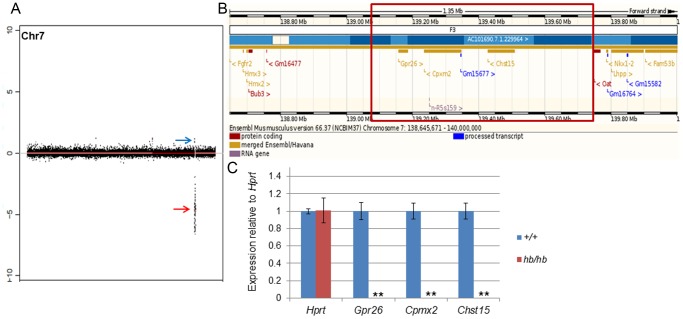

Figure 2. The headbobber mutation.

A: Plot showing the main genomic variations found by aCGH in 4 hb/hb on Chromosome 7: a 647.7 kb deletion in qF3, confirmed by deep sequencing (red arrow, loss of copy number, Chr7: 139061190–139708657, log ratio of −8.5) and a gain in qF3 (blue arrow, Chr7: 138832773–138832773, log ratio 1.3). B: Screenshot of the deleted region (www.ensembl.org). The red square delimits the breakpoints of the deletion. There are three protein coding genes in the region (Gpr26, Cpxm2 and Chst15), a non-coding RNA (n-R5s159) and an antisense RNA (Gm15677). C: Quantitative real-time PCR on cDNA generated from RNA from P1 cochleae show the absence of mRNA for Gpr26, Cpxm2 and Chst15 in hb/hb compared to the littermate controls. Error bars, s.d. Quantity normalised to Hprt1 levels. N = 3.**: p<0.01.

There are three protein coding genes annotated in the deleted region on Chromosome 7: G protein-coupled receptor 26 (Gpr26), carboxypeptidase X 2 (Cpxm2) and carbohydrate (N-acetylgalactosamine 4-sulfate 6-O) sulfotransferase 15 (Chst15) (Fig. 2B). Here we report their expression in the mouse inner ear at early postnatal days (Fig. 3), which suggests their deletion can contribute to the headbobber hearing phenotype.

Figure 3. Cochlear expression of genes in the headbobber deletion on Chr7.

A–B: Immunohistochemistry on ear sections at postnatal day five shows Gpr26 expression in spiral ligament fibrocytes (black arrowheads in A). We did not detect presence of Gpr26 in hb/hb cochleae at this stage (B). Scale bar: 10 µm. C–D: Immunohistochemistry on ear sections at postnatal day five shows Cpmx2 expression specifically in intermediate cells of stria vascularis (arrowheads in C). No protein was detected in hb/hb (B). Scale bars: 10 µm. E–H: Immunohistochemistry for Chst15 in hb/hb and control littermates at P5. At this stage, Chst15 shows expression in hair cells (arrowheads in E), marginal cells (black arrowheads in G) and their interdigitation to intermediate cells of stria vascularis (red arrowheads in G). As shown in F and H, we cannot detect any significant expression of Chst15 in hb/hb compared to littermate controls in the organ of Corti (F) and stria vascularis (H), although we can still detect a few protein dots (black arrowheads in F,H), which can either be an artifact or due to non-specific staining. Scale bar: 10 µm. I–J: Whole mount immunofluorescence of organ of Corti at postnatal day five shows expression of Chst15 (green) in the basal region of stereocilia of both inner and outer hair cells (arrows in I). We do not detect any Chst15 expression in the hb/hb disorganized hair bundles (arrowheads in J). Phalloidin (red) stains actin filaments of stereocilia. Scale bars: 10 µm. ohc: outer hair cells; ihc: inner hair cells.

Gpr26 (NM_173410.3) is an Orphan G-coupled receptor [35], [36]. It displays a significant level of constitutive activity and it is widely expressed in selected tissues of human brain as well as the developing and adult mouse brain [37]. Gpr26 deficient mice have been reported to show anxiety and depression-like behaviour [38]. We detect absence of Gpr26 expression in hb/hb compared to littermate controls throughout the whole cochlea (Fig. 3A,B). In wildtype mice at postnatal day five, Gpr26 expression is detected in the spiral ligament fibrocytes (Fig. 3A), in vestibular system fibrocytes and spiral ganglion (data not shown).

Cpxm2 (NM_018867.5) is transcribed from the opposite strand to Gpr26, so that they are actually back to back on Chr7. Cpxm2 has been proposed to be a binding protein with a role in cell adhesion, more than an enzyme [39]. It is reported to be expressed in mouse brain [39] as well as developing cochlea [40]. Our expression analysis shows Cpxm2 expression confined in intermediate cells of stria vascularis at P5 (Fig. 3C) and no expression is detected in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (Fig. 3D).

Chst15 (NM_029935.5) shows various physiological activities through interacting with numerous functional proteins [41] It is transcribed in the same direction as Gpr26 and it is reported to be expressed in developing brain [40], [42], bone marrow-derived mast cells [43] and early mouse embryos [41]. Mice deficient in Chst15 have not been tested for hearing impairment; however, their hematopoietic phenotype has been analysed and they exhibit decreased protease activity in bone marrow-derived mast cells [43]. We detect expression of Chst15 in the apical region of both inner and outer hair cells (arrowheads in Fig. 3E), as well as in their cell bodies. Consistent with the headbobber strial phenotype, we detect Chst15 expression in marginal cells and their interdigitations (black and red arrowheads respectively in Fig. 3G) in stria vascularis. Furthermore, we have observed its expression in the base of stereocilia by whole mount immunofluorescence (arrows in Fig. 3I), which could explain the stereocilia phenotype we observe in hb/hb, with extensive fusion at their base (Fig. 1G). As expected, we observe a complete loss of Chst15 in stereocilia of hb/hb compared to littermate controls (Fig. 3J). Our expression analysis showed absence of significant Chst15 expression in hb/hb organ of Corti and stria vascularis (Fig. 3F,H) compared to littermate controls.

Quantitative RTPCR on hb/hb cochleae from mice aged P1 confirmed absence of transcription for the three genes included in the deletion (Fig. 2C).

Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 homeobox transcription factors are downregulated in hb/hb

Among numerous candidate genes for the headbobber mutation which map in the hb region, our attention was focused on homeobox transcription factors Hmx3 (Nkx5.1, NM_008257.3) and Hmx2 (Nkx5.2, M_145998.3), as single and double knockout mice show a severe malformation of the vestibular region of the inner ear [10], [19], [44]–[46], similar to what we observe in the hb/hb mouse. Therefore, a complementation test was carried out between headbobber homozygotes and the Hmx3 KO mice [20]. We crossed +/Hmx3KO to hb/hb mice and observed that around half the offspring (those carrying one hb allele and one genotyped Hmx3KO) displayed a circling phenotype indicating non-complementation. Newborn compound heterozygotes were paintfilled and showed a severely affected inner ear structure. These mice have a fused saccular and utricular region and very rudimental posterior and superior semicircular canal. The cochlea develops normally, and looks similar to that of hb/hb mutants (Fig. 1C). The endolymphatic duct looks normal in hb/Hmx3KO compound mutants, excluding an essential role for Hmx3 in endolymphatic duct development, as already reported [44] (Figure S2). We measured compound action potential responses and endocochlear potentials in Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO, Hmx3KO/hb and littermate controls and detected a wide range of intermediate values in Hmx3KO homozygotes compared to hb/hb and littermate controls, while compound heterozygous Hmx3KO/hb show intermediate responses compared to hb/hb and Hmx3KO (Fig. 1N,O). These data suggest genetic interaction between Hmx3 and the genes affected by the headbobber mutation leading to multigenic inheritance of the inner ear phenotype. We sequenced the coding regions of Hmx3 and Hmx2 in the hb/hb mutants by Sanger sequencing and we did not detect any changes in the coding structure (data not shown). We then decided to analyse their expression levels in the headbobber inner ear at different stages of development, in order to understand whether the transgenic insertion associated with the mutation has any effect on their expression. Hmx3 is considered one of the earliest markers of inner ear development, as its expression is detected as early as E8.5 in the dorsolateral part of the otocyst [47]. We detect reduced labeling by in situ hybridisation of Hmx3 in the dorsal part of otocyst at E10.5 in hb/hb mutants compared with littermate controls (Fig. 4A,B). Hmx3 mRNA labelling is also reduced in hb/hb mutants compared to littermate controls at E12.5, suggesting again its involvement in the headbobber phenotype (Fig. 4C,D). At E12.5, Hmx3 expression is detected in the canal fusion plate, in the semicircular canals and in some cells in the utricle and in the saccule in control mice; its expression is restricted to non-sensory epithelial cells. Only a few non-sensory cells express detectable Hmx3 in the hb/hb vestibular structure (Fig. 4D) and the positive region could correspond to the fusion plate. As expected, Hmx3 is not expressed in the cochlea at this stage (data not shown). Reduced labelling for Hmx3 is detected by in situ hybridization in hb/hb brain compared to littermate controls (data not shown). As Hmx2 starts to be expressed only several hours after Hmx3 [46] we analysed its mRNA levels in the headbobber inner ear at E12.5 and, as expected, Hmx2 shows an overlapping spatial pattern of expression with Hmx3 at this stage, with expression in the epithelia of the canal plate, semicircular canals and in the utricule and saccule (Fig. 4E). In hb/hb, we detect reduced mRNA levels for Hmx2 in the vestibular system at this stage when compared to littermate controls, with only a few Hmx2 positive cells detected (Fig. 4F). As expected, Hmx2 is not expressed in the cochlea at this stage (data not shown). Moreover, we analysed the Hmx3 and Hmx2 protein levels in the inner ear by immunohistochemistry at postnatal day 5 in control mice, and we detect their expression in intermediate cells, as previously reported [47]. However, we do not detect any staining for Hmx3 and Hmx2 in hb/hb mutants. (Fig. 4 H–I, Figure S2A–B and data not shown).

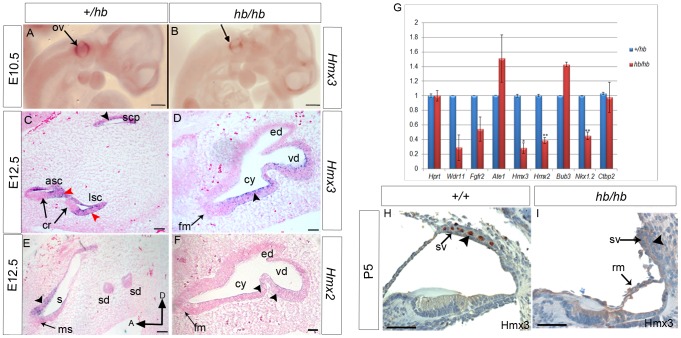

Figure 4. Expression analysis of Hmx3 and Hmx2 homeobox transcription factors in hb/hb and control littermates.

A–B: Hmx3 expression in hb/hb mutants tested by whole mount RNA in situ hybridisation at E10.5, showing decreased expression of Hmx3 in the dorsal part of the otocyst of hb/hb mutants compared to littermate controls (arrows) C,D: RNA in situ hybridisation for Hmx3 at E12.5 in vestibular system sagittal sections. In control littermates, Hmx3 RNA is detected in the canal fusion plate (black arrowhead in C), semicircular canals (red arrowheads in C), and in the utricle and saccule (not shown) but its expression is always observed in non-sensory epithelial cells as previously reported (C). In hb/hb mutants we still detect Hmx3 mRNA in the vestibular non-sensory regions compared to the littermate controls (arrowhead in D). E,F: Hmx2 expression in vestibular system detected by in situ hybridisation on sagittal sections from hb/hb and littermate controls at E12.5. In control mice, as previously reported, Hmx2 shows a similar expression pattern to Hmx3 in the non-sensory cells and in the canal plate, in the utricle (arrow in E) and in the canals (not shown). In hb/hb we detect Hmx2 expression only in a few cells in the non-sensory regions of the structurally abnormal vestibular system, compared to the littermate controls (arrowheads in F). Scale bars: A,B, 0.5 mm; C–F, 100 µm. G: Quantitative real-time PCR of cDNA generated from RNA from E12.5 littermate embryo half heads. Only Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 mRNA levels are significantly downregulated in hb/hb compared to littermate controls. Error bars, s.d. Quantity normalised to Hprt1 levels. N = 3. *:p<0.05; **: p<0.01. H–I: Expression of Hmx3 in hb/hb cochlear sections and control littermates at postnatal day five. After birth, Hmx3 is expressed in intermediate cells in stria vascularis (arrowhead in H, see also Figure S2). As it is clear in I, no Hmx3 staining is detected in hb/hb cochlea at P5, consistent with the loss of intermediate cells (arrowhead in I). Scale bars: 20 µm. a: anterior, asc: anterior semicircular canal, cr:cristae, cy: vestibular cyst, D: distal; ed: endolymphatic duct fm: fused maculae lsc: lateral semicircular canal mu: maculae utriculi ms: maculae sacculi; oc: organ of corti, ov: otic vescicle; rm: Reissner's membrane, s: saccule scp: superior canal plate; sd: semicircular duct; s+u: utriculosaccular space, sv: stria vascularis, vd: vestibular diverticulum.

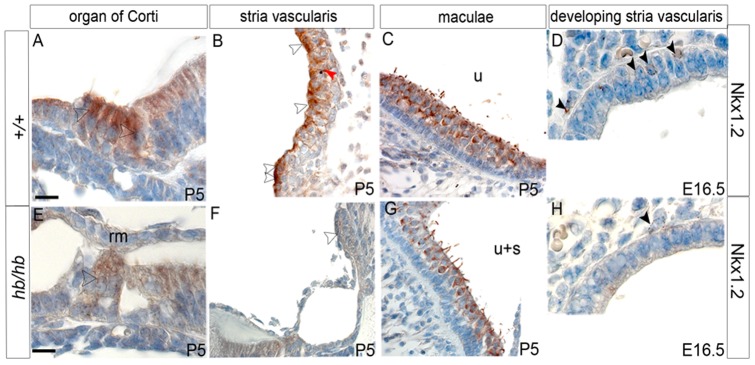

Quantitative RT-PCR confirms that Hmx2 and Hmx3 are significantly downregulated in mutant embryonic heads compared with controls (Fig. 4G), together with Nkx1.2 (NM_009123.2), another homeobox transcription factor (from the NK-1 class of homeobox genes) mapping in the headbobber locus in a reverse transcriptional direction to Hmx2 and Hmx3. Nkx1.2 has been reported as transiently expressed in the developing posterior CNS [48], but nothing is known of its expression in the inner ear and putative function in hearing. We sequenced its coding regions and did not find any mutation in hb/hb DNA (data not shown). Our expression analysis at postnatal day five shows that Nkx1.2 is expressed in inner and outer hair cells, marginal cells in the stria vascularis and sensory regions in the vestibular system (Fig. 5). Moreover, Nkx1.2 is expressed in prospective intermediate cells of the stria vascularis (melanoblasts) at E16.5 (Fig. 5D). Although we can detect nuclear staining (arrowheads in Fig. 5A,B), as expected, the transcription factor Nkx1.2 seems to be expressed in the cytoplasm as well, suggesting that the protein might need specific activation to translocate to the nucleus as has been observed for other transcription factors [49].The Nkx1.2 cochlear expression pattern clearly fits with the headbobber phenotype, suggesting a possible role for this homeobox transcription factor in melanoblast survival. Quantitative RTPCR confirms that Nkx1.2 expression in the inner ear is reduced at this stage compared to littermate controls (Fig. 5E,H).

Figure 5. Expression pattern of Nkx1.2 in hb/hb and control littermates at postnatal day 5.

Nkx1.2 shows expression in hair cells of organ of Corti (arrowhead in A), marginal cells and marginal cells processes in stria vascularis (white and red arrowheads in B, respectively) and hair cells in maculae (C) at P5. Moreover, Nkx1.2 is detected in the perinuclear area of melanoblasts in developing stria vascularis (arrowheads in D). Nkx1.2 staining is reduced in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (arrowheads in E–H). Scale bars: A,B,C,D,E,G,H: 10 µm; F: 20 µm.

We tested mRNA levels of other candidate genes in the headbobber region at E12.5, such as Wdr11 (NM_172255.3), Fgfr2 (NM_201601.2), Ate1 (NM_166380.2) Bub3 (NM_009774.3) and Ctbp2 (NM_009980.4) by quantitative RT-PCR and found no significant differences in levels (Fig. 4G). In the case of Fgfr2 [50] we also tested the inner ear expression pattern by immunohistochemistry at postnatal day five, but we did not detect any difference in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (Figure S2 E,F). These results suggest involvement of three homeobox transcription factors Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 in the headbobber phenotype, with the transgenic insertion not disrupting their coding sequences, but perhaps disrupting their (shared) regulatory elements on chromosome 7.Therefore, we used the TRANSFAC database [51] to map target binding sites (TFBSs) for 39 transcription factors, with a particular interest in those already reported to have a role in hearing and vestibular function [46], [52]–[54]. We discovered that Hmx2, Hmx3 and Nkx1.2 themselves, together with 10 other members of the Nkx gene family (table 1), are predicted to recognise high-affinity binding sites in the deleted region, suggesting a possible mechanism of transcriptional auto-regulation for these transcription factors. Moreover we found that a number of homeobox transcription factors have predicted binding sites in the deletion, including Emx2, Hoxa2, Otx1, Otx2, Lmx1a, Lmx1b, Pax2, Pax6, Six1 and Six2 (Table 1). Our analysis suggests that all these transcription factors might be involved in the regulation of Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 transcriptional levels.

Table 1. Transcription factors binding with high affinity in the region of the headbobber deletion on Chr7, identified with the use of the TRANSFAC database.

| Transcription Factor | Number of high affinity binding sites | Described role in inner ear development |

| Hoxa2 | 1 | + [78] |

| CREB | 3 | - |

| Pax2 | 25 | + [79] |

| Pax6 | 2 | - |

| Six1 | 2 | + [70], [80] |

| Six2 | 1 | + [81] |

| Sp1 | 2 | - |

| NF-X | 8 | - |

| Emx2 | 1 | + [82] |

| Oct-1 | 4 | - |

| Lmx1a | 1 | + |

| Lmx1b | 2 | + [83] |

| Otx1 | 2 | + [84], [85] |

| Otx2 | 2 | + [84], [85] |

| Nkx1.1 | 1 | - |

| Nkx1.2 | 1 | In this work |

| Nkx2.1 | 2 | - |

| Nkx2.2 | 1 | - |

| Nkx2.3 | 2 | - |

| Nkx2.5 | 1 | - |

| Nkx2.6 | 2 | - |

| Nkx2.9 | 1 | - |

| Nkx6.1 | 2 | - |

| Nkx6.3 | 4 | - |

| Hmx1 | 2 | - |

| Hmx2 | 1 | + [44] |

| Hmx3 | 1 | + [20] |

| Lhx1 | 1 | + [86] |

| NF-y | 2 | - |

| c-Fos | 2 | - |

Expression analysis of prosensory markers in the headbobber inner ear

The development of the inner ear is a very complicated process, which is characterized by a series of genetically programmed events. Although a good number of developmental regulators are known to be involved in this cascade of events, it is not yet clear what role these different genes play in development of the sensory patches, and in relation to one another [55]. In order to gain more insight on the role of the Hmx transcription factors Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 in this pathway, we have performed an expression analysis of molecular markers of key events in development on headbobber ear sections at different stages of development. This has been performed either by RNA in situ hybridisation or by immunohistochemistry.

The secreted factor Bmp4 is expressed in the developing cristae and in the cochlea at E12.5 (Fig. 6A–D, [56]. In hb/hb mutants, Bmp4 shows a comparable mRNA expression to littermate controls in the cochlea (Fig. 6C,D), with normal expression in the epithelium on the outer edge of the developing organ of Corti, confirming the normal establishment of this cochlear prosensory patch in the headbobber mouse model (Fig. 6D). As early as E12.5, as shown in Figure 6B, hb/hb already show an abnormal vestibular structure, with no presence of semicircular canals with their cristae but with formation of only one sensory patch in the utriculosaccular space (fused maculae, arrow in Fig. 6B). Bmp4 mRNA is detected in two regions which, according to the expression screening performed at later stages, are definitely not going to develop into sensory regions in the hb/hb mutants (white arrowheads in Fig. 6B). Most likely, the two positive regions could be early developing cristae that as a result of the headbobber mutation, fail to specify as a mature sensory patch at later stages. In fact, a similar scenario was observed in Hmx2 but not Hmx3 knockout mice [44], [45], all these data suggesting that Bmp4 might need full expression of Hmx2 for its role in driving final cristae specification.

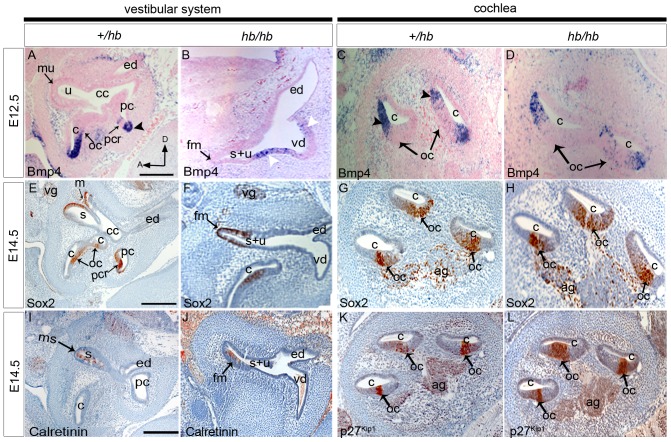

Figure 6. Summary of the expression patterns of selected markers of inner ear development, performed on sagittal sections from hb/hb mutants and littermate controls at different stages of development.

A–D: RNA In situ hybridisation for Bmp4 E12.5 in hb/hb and littermate controls. In control mice, Bmp4 expression overlaps with the pattern detected for Hmx3 and Hmx2, being expressed in the non-sensory cells adjacent to the organ of Corti and cristae (arrowheads in A and C). No Bmp4 expression is detected in maculae at that stage. (mu in A) In hb/hb, Bmp4 is expressed in two regions in the vestibular cyst (white arrowheads in B), which are definitely not adjacent to any sensory regions in the headbobber homozygotes at later stages. C,D: No difference in Bmp4 RNA levels has been detected in hb/hb mutant cochleae compared to their littermate controls. E–H: Sox2 immunohistochemistry in hb/hb and littermate controls at E14.5. In control mice, Sox2 is expressed in all the prosensory regions of the inner ear (arrows in E,G). In hb/hb vestibular system, Sox2 shows normal expression in the fused maculae (fm in F), which is the only vestibular prosensory patch we detect in hb/hb. Sox2 cochlear expression in hb/hb looks normal when compared with the littermate controls, suggesting a normal development of the organ of Corti at embryonic age E14.5. In addition, Sox2 marks the nuclei of both vestibular and cochlear ganglia (vg in E,F and ag in G,H), and again no differences in Sox2 expression have been detected in these cells at this stage of development. I–J: Expression of Calretinin at E14.5 of hb/hb and control littermates. At this stage Calretinin marks the developing hair cells. While the hair cells in the organ of Corti are not developing yet at this stage, a few hair cells start to develop in the maculae of normal mice (arrow in I). Calretinin expression analysis shows presence of a few normally developing hair cells in the fused maculae of hb/hb at this stage (arrow in J). K–L: p27Kip1 expression on hb/hb and littermate controls at E14.5. P27Kip1 at E14.5 is upregulated in cells of the sensory patch in the cochlea as they prepare to exit the cell cycle. Immunohistochemistry using P27Kip1 antibody demonstrates that in hb/hb mutants prosensory cells this marker is expressed in the same way in the hb/hb organ of Corti, compared to littermate controls (arrows in K,L). Scale bars: 200 µm A: anterior; ag: acoustic ganglion; c: cochlea; cc: common crus; cy: vestibular cyst;D: distal; ed: endolymphatic duct; fm: fused maculae; ms: maculae sacculi; mu: maculae utriculi; oc:organ of Corti; pc: posterior semicircular canal; pcr: posterior cristae; vg: vestibular ganglion; s:saccule; sv: stria vascularis; u:utricle; s+u: utriculosaccular space; vd: vestibular diverticulum.

The developmental stage E14.5 is crucial for studying inner ear development, as at this stage prosensory regions start to be established and prosensory cells start to exit the cell cycle to differentiate and become mature sensory cells. Sox2, a member of the group B Sox (SRY-related HMG box) transcription factor family, is required for establishment of the prosensory regions in the inner ear [57]. It is expressed in all the prosensory regions and the developing neurons that will be innervating the sensory hair cells in control mice. In hb/hb, Sox2 shows expression in the fused maculae, organ of Corti and ganglia (Fig. 6F,H). No evidence of crista formation has been observed in any of the homozygotes labelled with Sox2 (Fig. 6F). At E14.5 Calretinin antiserum labels the postmitotic differentiating hair cells [58] in maculae. Immunohistochemistry with Calretinin antibody showed expression in some cells in maculae sacculi, cristae and vestibular ganglion in control mice (Fig. 6I and data not shown) and a few labelled cells were observed in the fused maculae in hb/hb mutants (Fig. 6J). While at E14.5 hair cell differentiation has already started in maculae and cristae, in the organ of Corti this process starts a little bit later in development, and therefore we do not detect any calretinin expression in cochlea at this stage either in hb/hb or in littermate controls (data not shown). p27Kip1 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor which is upregulated in cells of the sensory patch in the cochlea as they prepare to exit the cell cycle [59]. Again, p27Kip1 has a comparable expression in hb/hb mutants and their littermate controls (Fig. 6K,L). All these results demonstrate that Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 do not act in early specification and differentiation of hair cells once the location of the sensory patches has been determined.

The headbobber stria vascularis remains immature with lack of intermediate cells and impaired basal lamina degradation

We investigated in detail the possibility that the lack of endocochlear potential in the hb/hb mutants could be directly related to a primary defect in stria vascularis, similar to what has been described for the melanocyte-deficient deaf mouse viable dominant spotting [25] and the Varitint-waddler-J deaf mutants [34]. In support of this hypothesis, we observed that the three genes deleted in headbobber show an intriguing expression in the stria vascularis after birth (Figure 3) as well as during development (data not shown).

To this purpose, we used an antibody to Myo7A [60] to detect the presence of neural crest-derived melanoblasts (precursors of intermediate cells) in the developing stria at E16.5, and we do not detect melanoblasts in the hb/hb developing stria compared to littermate controls (Fig. 1). However, we used Kcnq1 [61] as a marker for marginal cells and show that they are still present in the hb/hb abnormal stria vascularis (Figure S2 C,D).

In order to understand whether the lack of melanoblasts in the hb/hb stria is due to a problem in their migration from the neural crest to the inner ear or to a possible problem in their survival or differentiation, we used Trp2 as a marker for migratory melanoblasts from neural crest [6], [8]. As shown in Fig. 7A–C, Trp2 staining does not show an obvious difference in the number of melanoblasts migrating to the developing stria in hb/hb compared with littermate controls. Moreover, we still detect melanoblasts migrating to the developing stria in Hmx3KO, suggesting that Hmx3 is not required for melanoblast migration from the neural crest (Fig. 7C). This observation is consistent with the normal coat color displayed by hb/hb. In contrast with normal early migration, we show that some melanoblasts have differentiated at E16.5 in hb/hb, but these remain outside the stria vascularis, while we can already observe a group of melanoblasts starting to interdigitate into the developing strial epithelium in control mice (Fig. 7D–E), supporting our observations with Myo7A staining at the same age (Fig. 1L,M). Moreover, hematoxylin-eosin counterstaining of the Trp2 stained sections highlights that the epithelial cells look under-differentiated in hb/hb, retaining their cuboidal shape with rounded nuclei, while in control mice cell nuclei are flattening and intermediate cell precursors are entering the developing stria (Arrows in Fig. 7 D,E). We obtained the same results using c-kit as a marker of melanoblast survival at E16.5. [6] (data not shown).

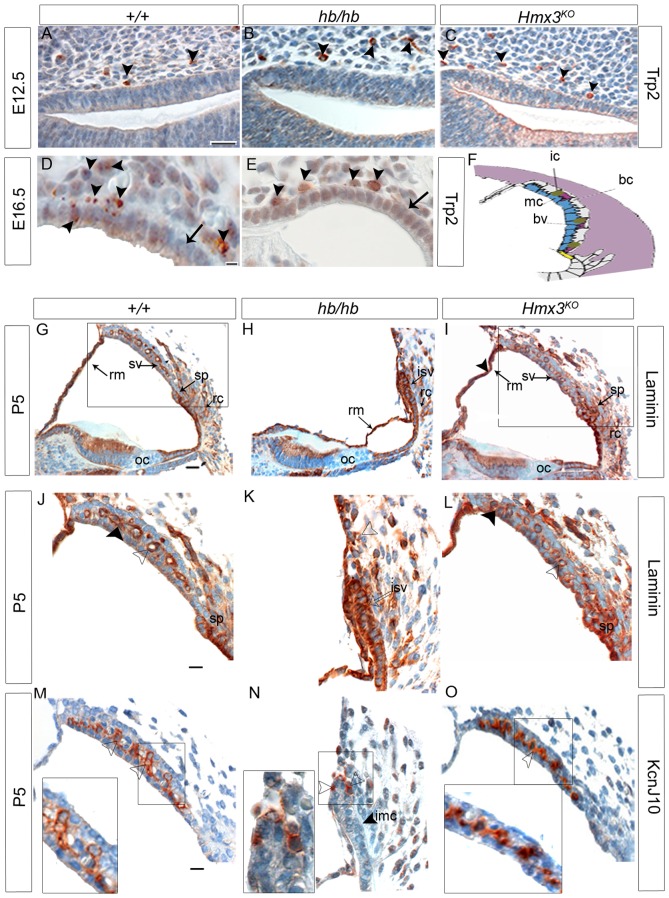

Figure 7.

A–E: Trp2 expression performed on inner ear sagittal sections in hb/hb, Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO and control littermates at E12.5 and E16.5. A–C: Trp2 marks neural crest-derived melanoblasts at E12.5 (arrowheads in A). As shown by the arrowheads in B and C, we detect melanoblasts migrating from the neural crest to developing stria is detected in hb/hb, Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO, and littermate controls. D–E: While in control mice at E16.5 some intermediate cells precursors are already in the process of interdigitation in the developing stria vascularis (arrowheads in D), none are in the same process in the hb/hb mutants with only a couple of them lying outside the epithelium (arrowheads E). Moreover, Hematoxylin and Eosin counterstaining shows that the epithelium of developing stria looks immature in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (arrows in D,E). Scale bars: 10 µm. F: Cartoon of the cellular structure of stria vascularis. Adapted from [77]. G–I: Immunohistochemistry showing Laminin expression in cochlea and general cochlear morphology of hb/hb, Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO and control littermates at P5. Laminin is expressed in all cochlear basal lamina [63], including stria vascularis, Reissner's membrane, root cell processes and spiral prominence (arrows in G). J–L: Laminin expression in stria vascularis of hb/hb, Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO and control littermates at P5. At this stage, we detect basal lamina in blood vessel endothelia (arrowhead in J) and in very small pockets below marginal cells (black arrowhead in J) in control mice. In hb/hb we detect a much stronger laminin expression (denser basal lamina) around the immature stria vascularis (arrow in K). Moreover, we observe fewer and smaller blood vessels in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (examples of blood vessels are labeled with transparent arrowheads in J,K,L). We did not detect any difference in laminin expression in Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO compared to littermate controls (arrowhead in L). M–O: Kcnj10 expression in the stria vascularis of hb/hb, Hmx3KO mutants and control littermates at P5. Kcnj10 is an inward potassium channel of intermediate cells. We detect only some intermediate cells in hb/hb mutants (arrowheads in N) compared to their littermate controls at this stage (M). These intermediate cells are just outside the undifferentiated strial epithelium (the black arrowhead in N points to the immature marginal cell layer in hb/hb, see also Figure S1). No difference in Kcnj10 expression is detected in Hmx3KO/Hmx3KO at this stage compared to control littermates (arrowhead in O), consistent with their EP values being close to normal. Boxes delimit regions in higher magnification. Scale bars: A–E: 20 µm; G,I: 10 µm; J–O; 20 µm. bc: basal cells, bv: blood vessels, ic: intermediate cells, imc: immature marginal cells, isv: immature stria vascularis, oc: organ of Corti, rc: root cell processes, Rm: Reissner's membrane, sp: spiral prominence, sv: stria vascularis.

Controlled basal lamina degradation is a key mechanism in morphogenesis of complex organs and is the main molecular event in morphogenesis of both stria vascularis, where marginal cells are derived from the epithelium and sit on a basal lamina [21], and the vestibular system [62]. In this work, we demonstrate that both tissues fail to develop properly in hb/hb compared to littermate controls, leading to loss of melanoblast interdigitation into the developing stria vascularis.

We therefore analysed laminin expression as a marker of basal lamina [63] in hb/hb, Hmx3KO and littermate controls at postnatal day 5. At this stage in control mice, basal lamina underlying the marginal cell layer is almost completely disintegrated to allow melanoblasts to interdigitate into the strial epithelium as well as the extensive formation of marginal cell processes [64]. In fact, we detect basal lamina only in blood vessel endothelia and in very small pockets between marginal and intermediate cells in control mice (Fig. 7 G,J), whereas in hb/hb, supporting what we have already seen as early as E16.5, the strial epithelium looks under differentiated in the abnormal mutant stria, with a much stronger laminin expression throughout the lateral wall (Fig. 7K). We also confirmed the abnormal persistence of basal lamina below the epithelial marginal cells in hb/hb by transmission electron microscopy of the stria vascularis (Figure S3C). These data suggest a delayed or abnormal differentiation of strial epithelium in hb/hb mutants compared to littermate controls. No major differences have been detected with laminin expression in Hmx3KO compared to littermate controls (Fig. 7I,L), excluding a unique role for Hmx3 in controlling basal lamina degradation, supporting what has already been reported by [44]. We used the Kcnj10 potassium channel as a marker of intermediate cells [65] at P5, and confirmed that the melanoblasts that survive and differentiate to express Kcnj10 in the hb/hb inner ear did not interdigitate into the developing epithelium, since the basal lamina is not broken to allow normal intermediate cell interdigitation. These intermediate cells lie just outside the immature marginal cell layer in hb/hb, as shown in Fig. 7N, while a healthy intermediate cell layer can be observed in control mice and Hmx3KO stria vascularis (Fig. 7O).

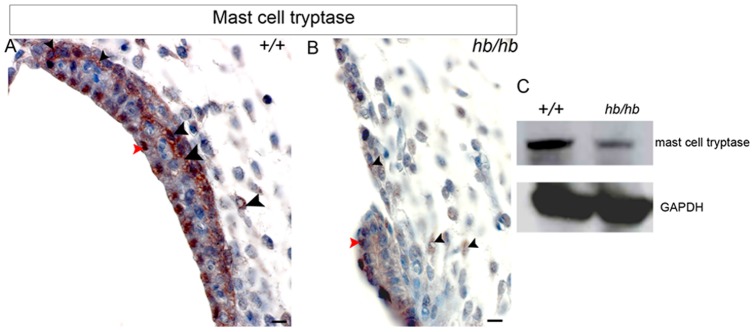

Finally, we analysed the expression levels of mast cell tryptase, a trypsin-like serine protease that is released by activated mast cells and has been shown to trigger the degradation of extracellular matrix [66], with the aim of checking whether mast cell release of protease could also play a key role in basal lamina digestion in stria vascularis development. We detect decreased levels of mast cell tryptase in hb/hb stria vascularis compared to littermate controls (Fig. 8 A,B,C), in line with what was observed in Chst15 deficient mice in bone marrow-derived mast cells [43].

Figure 8. Expression of mast cell tryptase in hb/hb and control littermates stria vascularis at postnatal day five.

A,B: At this stage, our immunohistochemistry detects serine protease expression in proximity of blood vessels and intermediate cells (black arrowheads in A) and nuclei of marginal cells (red arrowhead in A), in line with the mast cell tryptase being involved in DNA synthesis stimulation in some cell types [66]. In hb/hb stria we detect reduced protein levels of mast cell tryptase compared to littermate controls, mostly close to its small capillaries (black arrowheads) and marginal cells (red arrowhead). Scale bar: 10 µm. C: Extracts from hb/hb and control littermate inner ears at P5 were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blots were probed with anti-mast cell tryptase antibody. GAPDH is used as loading control.

Basal lamina degradation is also impaired in hb/hb vestibular system

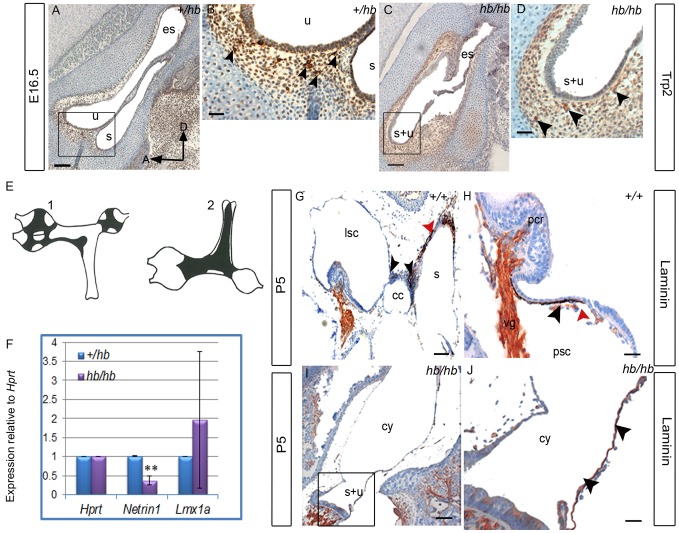

We also used Trp2 as a marker of melanoblasts migrating from the neural crest to the vestibular system at E16.5, as well as performed laminin staining at P5 on vestibular system serial sections of hb/hb and control littermates. Consistent with what observed in stria vascularis, melanoblast migration from neural crest to the vestibular system appears normal in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (Fig. 9A–D). As expected (Fig. 9E), in controls we find melanocytes on boundaries between vestibular structures as well as on the saccular wall and adjacent to cristae (Fig. 9G–H). Moreover, we observed that basal lamina is degraded close to melanocytes suggesting a possible signaling interaction between them. We cannot detect melanocytes in the vestibular system of hb/hb mutants at this stage but instead we detect laminin forming an immature dense basal lamina surrounding the fused utriculosaccular space in the hb/hb vestibular cyst, where melanocytes would normally be positioned at this stage (Fig. 9I,J). An intermediate scenario is observed in Hmx3KO vestibular system (data not shown).

Figure 9. The headbobber stria vascularis remains immature with lack of intermediate cells and impaired basal lamina degradation.

A–D: Trp2 expression in the vestibular system at E16.5 is analysed by immunohistochemistry in the hb/hb and control littermates on sagittal sections. At this stage, melanoblasts have already reached all the different vestibular structures (arrowheads in B, see E). We can still detect amelanoblasts in hb/hb vestibular system (arrowheads in D). Scale bars: A,C: 100 µm; B,D: 20 µm. Boxes delimit regions in higher magnification. E: Schematic drawings of the flattened vestibular membranes of normally pigmented mice showing distribution of melanocytes in the vestibule viewed on medial (E1) and lateral (E2) position, adapted from [7]. F: Quantitative real-time PCR on cDNA generated from RNA from E12.5 littermate embryo half heads. Netrin-1 mRNA levels are significantly lower in hb/hb than in littermate controls. Error bars, s.d. Quantity normalised to Hprt1 levels. N = 3. **: p<0.01. G–J: Laminin staining in the vestibular system of hb/hb and littermate controls at P5. In controls, we find melanocytes between the common crus and the other vestibular structures (black arrowheads in G) as well as on the saccular wall (red arrowhead in G) and adjacently to cristae (black arrowhead in H). We show that basal lamina is breaking close to melanocytes (red arrowhead in H). We cannot detect any distinct structure nor melanocytes in the vestibular system of hb/hb mutants at this stage (I,J), but we detect the presence of an immature and tight basal lamina all around the vestibular cyst wall, where melanocytes are supposed to be positioned. (black arrowheads in J compared to H). Scale bars: 10 µm. A: anterior, cc: common crus, cy: vestibular cyst, D: dorsal, es: endolymphatic sac, lsc: lateral semicircular canal, pcr: posterior cristae, psc: posterior semicircular canal,,s: saccule, s+u: utriculosaccular space, u: utricle.

Our data suggest a possible role of melanocytes in regulating basal lamina degradation, permitting the normal morphogenesis of stria vascularis as well as vestibular structures.

Netrin-1, a member of the laminin-related secreted proteins, is required for the local disruption of basal lamina. It is expressed at high levels in the nonsensory otic epithelium, in cells that will come together to form a fusion plate, a prerequisite for the formation of semicircular canals [62]. Remarkably, the Netrin1-positive domains in the wild-type otic vesicle were lost in the double Hmx2KO;Hmx3KO inner ears [45]. We detect a significant reduction of Netrin-1 mRNA levels in hb/hb at E12.5 compared to littermate controls (Fig. 9F). Since no effect on Netrin-1 expression has been observed in either Hmx2 or Hmx3 single mutants, reduced expression of this gene in both the double Hmx2 and Hmx3 mutants and headbobber indicates that Hmx2 and Hmx3 may function in a mutually redundant way in regulating Netrin-1 during development, and may act through Netrin-1 in controlling basal lamina degradation (thus morphogenesis) of the vestibular system.

Finally, one of the Lmx1a functional null mutants, dreher (drJ/drJ), shows a similar vestibular phenotype to headbobber [67], so we have investigated whether Lmx1a mRNA levels are affected in hb/hb. Quantitative RTPCR at E12.5 show extremely variable levels of Lmx1a mRNA in hb/hb compared to littermate controls (Fig. 9F), and this might be the sign of a mutual transcriptional regulation between Hmx3, Hmx2 and Lmx1a, confirming our results from the TRANSFAC analysis.

Discussion

We found the headbobber combined morphogenetic and cochleoaccular phenotype is due to the insertion of 4 copies in tandem of a transgenic construct on the distal region of mouse Chr7 between D7Mit105 and D7Mit12 associated with a 648 kb deletion on Chr7 F3, and this is in line with what reported by Somma et al in [4]. The mutation results in the deletion of Gpr26, Cpxm2 and Chst15, as well as disruption of the normal expression of the Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 homeobox transcription factors in the inner ear presumably as a consequence of a long-range effect of the mutation on the transcription of neighboring genes. Homozygotes show a severe equilibrium problem starting from two to three weeks of age, with head bobbing and circling and they are completely deaf. The characterisation of the headbobber inner ear phenotype has highlighted a very abnormal structure of the vestibule in hb/hb which totally explains the abnormal behaviour, with the absence of all the semicircular canals and the three cristae. The vestibule looks like a simple cyst with the saccule and the utricle fused together in a single utriculosaccular sac and the formation of a single macula. Moreover, despite normal cochlear gross morphology, headbobber homozygotes show a primary cochleo-saccular defect at early postnatal stages, characterised by under-differentiation of stria vascularis and collapse of Reissner's membrane, consistent with what was reported previously [4].

In addition to the data previously published, we show by SEM that in the organ of Corti both inner and outer hair bundles look severely disorganized as early as P5 in hb/hb, compared to littermate controls. We have been able to characterise the expression of the three protein coding genes mapping in the headbobber deletion (Gpr26, Cpxm2 and Chst15), and show that they all have an interesting expression in the inner ear, which completely fit with the headbobber phenotype. We also use headbobber to gain more insights on the Hmx2, Hmx3 and Nkx1.2 genetic interactions and transcriptional regulation, and report for the first time a putative role of Nkx1.2 in inner ear development. Moreover, we show the failure of intermediate cells to integrate into the strial epithelium, associated with complete absence of endocochlear potential. We also analysed the molecular mechanisms behind each aspect of the headbobber phenotype, and find that failure of the basal lamina to regress can explain several key aspects of the pathophysiology and that melanoblasts and mast cells may have a role in this process. Finally, we found a human equivalent of the headbobber mutation, and in this work we review the relevant clinical cases.

The headbobber deletion

Genetic tools (aCGH and deep sequencing) allowed us to narrow down the headbobber region and discover a big deletion on Chr7 cytoband F3 (Chr7: 139061190–139708657), strongly suggesting this might be the main effect of the transgenic insertional mutation in the headbobber allele, leading to the headbobber inner ear phenotype. These results are in line with our genetic mapping of the phenotype and the transgene, and with the results reported previously [4]. The deleted region contains three protein coding genes: 1) Gpr26, an orphan G-coupled receptor; 2) Cpxm2, a carboxypeptidase predicted to act as a binding protein; 3) Chst15, a carbohydrate sulfotransferase. For the first time, we report their expression in the murine inner ear and we link them to both mouse and human deafness. In detail, Gpr26 is expressed in the spiral ligament after birth, and recycling potassium though the fibrocyte network is one of several processes that provide potassium to intermediate cells of the stria vascularis, an essential process for normal cochlear function [68], [69]. Cpxm2 shows specific expression in the intermediate cells of stria vascularis at P5 which fits with the intermediate cell phenotype observed in hb/hb as early as E16.5 and subsequent absence of endocochlear potential. Finally, we detect Chst15 expression in the basal region of stereocilia and cell body of both inner and outer hair cells as well as in marginal cells and their interdigitations in stria vascularis. This is consistent with both the stereocilia disorganisation- showing fusion at their base - and the strial developmental failure observed in the homozygote mutants. Taken together, our results show that in this particular region of Chr7 there is an interesting group of genes playing an important role in stria vascularis development and auditory function. Their absence, together with the reduced expression of Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2, which are located at the same chromosomal region, causes deafness and vestibular problems both in mice and humans.

Headbobber is an hypomorphic mutation of Hmx3 and Hmx2

Hmx3 lies about 8 kb away from Hmx2 on Chr7, and the striking similarity in their expression patterns and in the sequence of their homeodomains, as well as their close proximity on the chromosome, raises the possibility that Hmx2 and Hmx3 may share common regulatory elements and have overlapping developmental functions, as previously discussed [46]. Our hypothesis is that the transgene has disrupted their regulatory elements and that is consistent with many observations: 1) The insertion of the hb transgene causes a deletion of about 648 kb in the distal part of chromosome 7F3, approximately 375 kb telomeric to the Hmx3 and Hmx2 locus; 2) We confirmed by Southern blot and DNA sequencing that the coding sequences of Hmx3 and Hmx2 are physically present on Chr7 in hb/hb mice; 3) Low Hmx3 and Hmx2 mRNA levels have been detected in hb/hb when compared to levels observed in the littermate controls at E12.5 (in line with what reported in [4]); and 4) A complementation test was carried out between headbobber homozygotes and the +/Hmx3KO mice, with the compound heterozygotes showing circling behaviour and intermediate vestibular abnormalities as well as endocochlear potential values, which suggests that downregulation of Hmx3 may contribute to the headbobber phenotype.

The headbobber vestibular phenotype is more severe than the one displayed by either the Hmx2 or Hmx3 single knockouts and these observations are in complete accordance with the suggestion of their redundant function in the inner ear [46]. On the other hand, the headbobber vestibular phenotype is less severe than the one displayed by the Hmx3/Hmx2 double knockout, which does not develop any vestibular system [45], which is consistent with the headbobber mutation being hypomorphic for Hmx2 and Hmx3.

A new putative role for Nkx1.2 in inner ear development

Our results show the downregulation and, for the first time, the potential involvement of another member of the Hmx family of transcription factors in the headbobber phenotype: Nkx1.2, which might share regulatory elements with Hmx3 and Hmx2 on Chr7. This gene has already been reported to be transiently expressed in the developing central nervous system [48] and in this work we describe its expression in the developing as well as in the postnatal stria vascularis; in fact, its expression shifts from prospective intermediate cells during development to marginal cells and their projections at postnatal stages. At P5, Nkx1.2 is also expressed in organ of Corti (inner and outer hair cells) and vestibular maculae. Therefore, we can hypothesise for the first time a role for Nkx1.2 in inner ear development and of particular interest is its potential role in controlling melanoblast survival (see further discussion).

Potential interactions suggested by the TRANSFAC analysis

We found that Hmx2, Hmx3 and Nkx1.2 themselves, together with many other homeobox transcription factors with known function in inner ear development such as Emx2, Hoxa2, Otx1, Otx2, Lmx1a, Lmx1b, Pax2, Pax6, Six1 and Six2, are predicted to recognise high affinity binding sites in the deleted sequence. These analyses suggest that they might play a role in the regulation of Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 transcriptional levels. Six1 has already been shown to repress Hmx3 and Hmx2 expression in the ventral part of the otocyst [70], although Pax2 deficient mice do not show any change in either Six1 or Hmx3 expression levels [71]. This observation suggests that Six1 and Hmx3 (but not Pax2) may act in the same transcriptional pathway, with Six1 acting upstream of Hmx3 and Hmx2. Moreover, both the Otx1 and the Otx2 deficient mice show an incomplete separation of the utricle and saccule [72] similar to the Hmx3 and Hmx2 knockouts, suggesting that they might also act in the same pathway. Finally, our quantitative RT-PCR shows a possible mutual transcriptional regulation between Hmx3, Hmx2 and Lmx1a.

The headbobber mutation affects early crista specification but does not affect early hair cell differentiation

While the function of the Hmx genes in the inner ear has been extensively studied, very little is known about their genetic interactions. Headbobber might be a good model to study the role of Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 in inner ear development and place them in a cascade of events. To this purpose, the expression of genes with a demonstrated role in inner ear development has been examined on wild-type and hb/hb inner ear sections at different embryonic stages.

Analysis of hair cell differentiation using Sox2 (marker for the prosensory regions), Calretinin (marker for the developing hair cells), p27Kip1 (sensory regions), and Jag1 (mature supporting cells, data not shown) showed no overt alteration in their expression in the remaining sensory patches of the hb/hb inner ear. This suggests a normal spatio-temporal development of the only two prosensory and sensory regions that form in the hb/hb mice, which are the fused maculae and the organ of Corti. So we can conclude that when a patch forms, it can fully differentiate. Either the lack of a gene regulatory relationship between the three homeobox genes and the genes involved in the development of sensory patches or the inability of these three genes alone to alter the regulatory cascade may account for these findings.

We reveal a possible interaction between Hmx3, Hmx2, Nkx1.2 and the bone morphogenetic protein 4 (Bmp4) by detecting the Bmp4 RNA in hb/hb mice. At E12.5, during fusion plate formation, Bmp4 transcripts are detected in the developing cristae of wild type mice and are absent in the fusion plate. However, despite the absence of recognizable cristae in hb/hb Bmp4 transcripts were found in two regions of the vestibular system in hb/hb embryos, at this stage. Further expression analysis of Bmp4 expression in hb/hb at E16.5 failed to detect Bmp4 transcripts in the vestibular system at this later stage (data not shown). These observations suggest that in hb/hb the cristae might be specified initially but fail to develop properly in the absence of Hmx genes, perhaps meaning that Bmp4 alone is not able to specify a prosensory region (crista). Hmx3 and Hmx2 might regulate the spatio-temporal expression of Bmp4, possibly acting on its promoter regions [36]. As we detected Hmx2, Hmx3 and Bmp4 transcripts in the non-sensory epithelial cells surrounding cristae in control mice, one might suppose that their interaction is crucial to control sensory cell fate determination. As we have detected a downregulation of Netrin-1 expression in hb/hb compared to littermate controls, we can conclude that Hmx3, Hmx2 and Nkx1.2 might play a role in controlling Netrin-1 transcription in the inner ear and therefore we suggest that Netrin-1 might be a downstream target of Hmx genes in the vestibular system.

A proposed mechanism to explain both the hearing and vestibular phenotypes shown by the headbobber mutant

Controlled basal lamina degradation is a key mechanism in morphogenesis of complex organs such as the vestibular system and stria vascularis in the inner ear. Although still little is known about its molecular mechanisms, mouse models have given important insights, and we now know for example that Netrin-1 and Hmx2 are required for the local disruption of the basal lamina by acting in epithelial-mesenchymal signalling during semicircular canal formation [44], [62]. We propose the impairment of the normal process of degradation of the basal lamina as an explanation for both deafness and the vestibular phenotype displayed by headbobber homozygous mutants. Controlled basal lamina degradation occurs starting from E12.5 in vestibular system development (at the canal pouch stage) [73], and this is exactly when we can start detecting the hb/hb vestibular abnormality. On the other hand, controlled basal lamina degradation to allow cytodifferentiation in strial epithelium with the initial interdigitation of intermediate cells, followed by formation and extensive elongation of marginal cell processes, happens later in development. By postnatal day five the basal lamina underlying the marginal cell layer is almost completely disintegrated [25].