Abstract

A 36-year-old man visited Yeungnam University Hospital with a sudden onset of palpitation, headache, and was found to be hypertensive. Chest radiography showed a 6 cm sized mass lesion on the posterior mediastinum. A biochemical study showed elevated levels of catecholamines. An I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine scan revealed a hot uptake lesion on the posterior mediastinum. The patient was prepared for surgery with α and β blocking agents. Two months later, we removed the tumor successfully. A histological study proved that the resected tumor was mediastinal pheochromocytoma. Functional mediastinal pheochromocytomas are rare. Therefore, we reported the case with a literature review.

Keywords: Mediastinum, Surgery, Hypertension, Pheochromocytoma

CASE REPORT

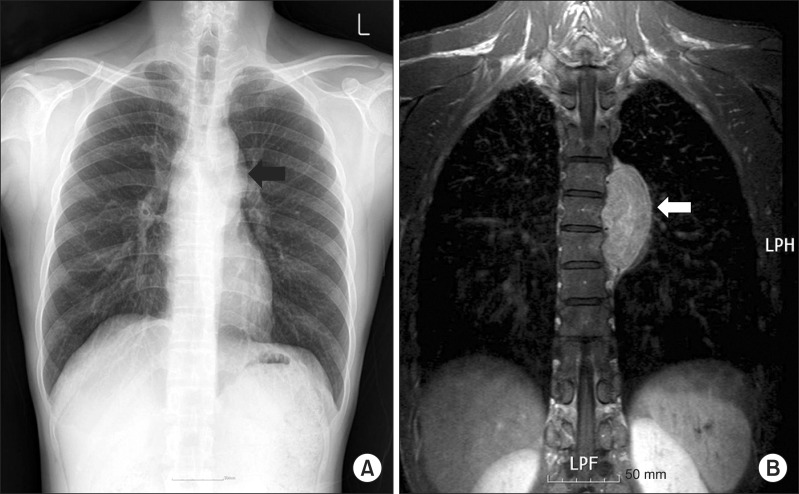

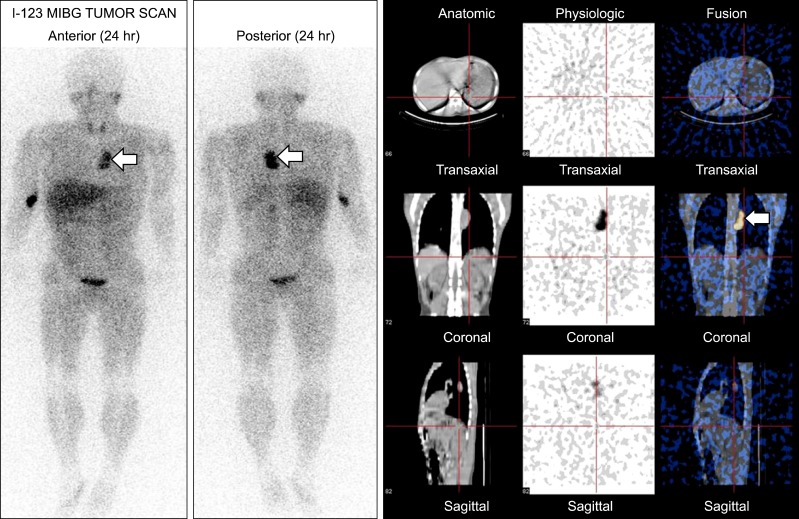

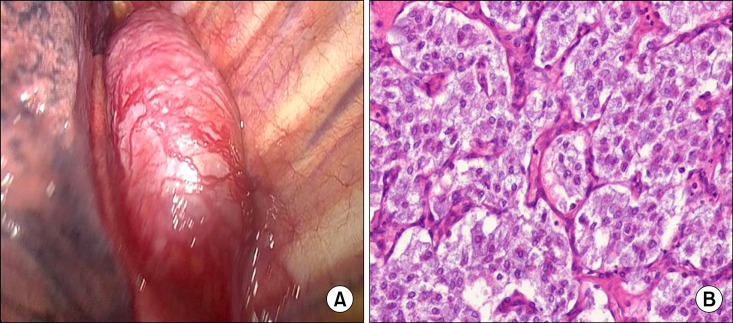

A 36-year-old man visited the emergency department. He had suffered from a sudden onset of chest pain, headache, palpitation, and dizziness. His pulse was regular, bounding, and at a rate of 119 per minute, and his blood pressure was at 190/120 mmHg. Electrocardiography and echocardiography were normal. Chest X-ray showed an oval-shaped mass lesion on the left paravertebral area (Fig. 1A). Chest computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a left paravertebral mass in the region of T4-T6, measuring at 3×6 cm, which was not invasive to the adjacent organs (Fig. 1B). There was no specific finding on abdomen CT. The biochemical studies showed elevated levels of serum norepinephrine (12.905 ng/mL; normal limit [nl], 0 to 0.8 ng/mL), urine norepinephrine (4,946 µg/day; nl, 15 to 80 µg/day), urine metanephrine (4.2 mg/day; nl<0.8 mg/day), and urine vanillylmandelic acid (26.6 mg/day; nl, 0 to 8 mg/day). The serum and urine epinephrine levels were normal. The presence of the tumor was confirmed using an I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan, along with its isolated nature (Fig. 2). In order to control the blood pressure and prepare for surgery, we administered α and β blocking agents to the patient. During the first three weeks, Concor (5 mg), Norvasc (5 mg), Atacand (8 mg), and Xyrem (0.25 mg) were administered. When visited the outpatient department, his blood pressure was near normotensive, but tachycardia and chest discomfort were still present. Therefore, we changed the medication to Cardura-XL (4 mg) for five weeks. The patient no longer felt chest discomfort, but tachycardia was still present. The heart rate was controlled (100 beat/min) after we administered Concor (2.5 mg). Two months after his first visit, we performed the operation. The tumor was found lying on the left paravertebral sulcus, which was hypervascular and well demarcated (Fig. 3A). We performed thoracoscopic resection, but there were transient changes in the blood pressure, which ranged from 130/90 to 200/120 mmHg; therefore, we converted to thoracotomy. In the intraoperative period, we controlled the blood pressure with Brevibloc and Perdipine. After the tumor was resected, the blood pressure dropped sharply. Therefore, we stopped administering antihypertensive drugs, and then the blood pressure remained stable. The resected tumor measured 6.5×4.0×3.0 cm and weighed 47.5 g. Histopathological examination confirmed the tumor to be pheochromocytoma (Fig. 3B). During the postoperative period, the patient remained normotensive without the need of antihypertensive drugs. He was discharged on the postoperative day 8. Two months later, the follow-up biochemical studies showed decreased levels of serum norepinephrine (1.108 ng/mL), urine norepinephrine (149.3 µg/day), urine metanephrine (1 mg/day), and urine vanillylmandelic acid (7.1 mg/day). The patient was asymptomatic with normal blood pressure and without taking antihypertensive drugs for more than 1 year.

Fig. 1.

Radiologic studies of the patient. (A) Chest posteroanterior shows well defined mass density at left paravertevral area (black arrow). (B) Chest magnetic resonance imaging shows a 7 cm sized well dermacated mass lesion at left posterior mediastinum (white arrow). Adrenal gland and adjacent structures are normal findings.

Fig. 2.

I-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) tumor scan shows hot uptake in left paraspinal area (arrow) and another metastatic lesion is not observed.

Fig. 3.

(A) Operative findings. About 3×6 cm sized well dermacated, hypervascular mass at left paravertebral area extending from T4-T6 level. (B) Histopathology of the resected specimen. It shows characteristic zellballen pattern with thin fibrovascular septa (H&E, ×200).

DISCUSSION

Pheochromocytoma develops from the chromaffin cells of the sympathetic nervous system [1-3]. In most cases, pheochromocytoma originates in the adrenal gland, but it can arise anywhere on the paraganglion tissues that contain chromaffin [1]. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma, often known as paraganglioma, is rare in adults (approximately 10%) and it occurs in thorax in 1% of the cases [1,4,5]. Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas are associated with several well-known inherited syndromes such as multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIA, IIB, or III, von Hippel-Lindau disease, von Recklinghausen's disease, and Sturge-Weber syndrome. Patients with any of these syndromes have familial histories [4,6,7]. Most pheochromocytomas are catecholamine-secreting, hyperfunctioning tumors, which cause symptoms such as hypertension, headache, palpitations, sweating, and weight loss resulting from the excess production of catecholamines. Such excess production leads to elevated levels of catecholamines in the blood, or increases the level of metabolites in the urine [6]. Thus, blood and urine examinations are useful for diagnosing functional pheochromocytoma. Paragangliomas are easily located using a CT scan, a MRI, or an I-131 MIBG [1,6,8]. Surgical resection is the preferred treatment for paraganglioma. Before the operation, a combination of α and β adrenergic blockades are required to control blood pressure and to prevent intra-operative hypertensive crises [2,3]. Preoperative adrenergic blockades are used until the patient's symptoms subside. The end point is normotension or near normotension, with slight postural hypotension and elimination or reduction of paroxysmal spells [3,6]. We also administered α and β blocking agents to the patient for two months until the operation date. Intraoperative monitoring by an experienced anesthesia team is very important because the patient's blood pressure and heart rate fluctuate very severely [2,6]. When the operators touch the tumor directly, the blood pressure and heart rate increase rapidly; therefore, blunt dissection through thoracotomy should be excluded and video-assisted thoracic surgery is performed rarely on thoracic lesions [1]. In our case, we attempted to perform thoracoscopic resection, but we experienced severe fluctuation of the vital signs; therefore, we converted to thoracotomy for resection of the tumor. After the tumor was resected, the blood pressure dropped sharply. Thus, the central venous line should be prepared in order to facilitate rapid volume resuscitation and an appropriate α agonist injection [6]. In our case, the blood pressure also dropped sharply after resection of the tumor. Because paragangliomas have a higher recurrence rate than pheochromocytomas, long-term postoperative follow-up is necessary [1,6]. When previous symptoms reoccur, it indicates recurrence of a tumor. Annual measurement of blood pressure and the urinary catecholamine metabolites is necessary. Performing CT or MRI may be helpful, and I-123 MIBG scanning is often used for detecting metastasis and recurrence of the disease [6].

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Sakamaki Y, Yasukawa M, Kido T. Pheochromocytoma of the posterior mediastinum undiagnosed until the onset of intraoperative hypertension. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:509–511. doi: 10.1007/s11748-008-0282-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh J, Rana SS, Sharma R, Ghai B, Puri GD. A rare cause of hypertension in children: intrathoracic pheochromocytoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:865–867. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young WF., Jr Paragangliomas: clinical overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1073:21–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1353.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung LC, Liu YS, Tsai YS, Chuang MT. Familial paraganglioma syndrome. Acta Neurol Belg. 2011;111:255–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faria J, Valente V, Lima P, Silva JA, Polonia J. Paraganglioma: a case of secondary hypertension. Rev Port Cardiol. 2010;29:1583–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spector JA, Willis DN, Ginsburg HB. Paraganglioma (pheochromocytoma) of the posterior mediastinum: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1114–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petri BJ, van Eijck CH, de Herder WW, Wagner A, de Krijger RR. Phaeochromocytomas and sympathetic paragangliomas. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1381–1392. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao S, Mullins ME, Slanetz PJ. Posterior mediastinal pheochromocytoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1408. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]