Highlights

► The p38 MAPK signaling pathway regulates cardiac remodeling. ► Human cardiac fibroblasts express the α, γ and δ subtypes of p38 MAPK. ► IL-1 selectively stimulates p38α and p38γ activation. ► p38α is important for IL-1-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 expression in cardiac fibroblasts.

Keywords: p38 MAPK, Cardiac fibroblasts, Heart, Interleukin, Matrix metalloproteinase

Abstract

Pre-clinical studies suggest that the p38 MAPK signaling pathway plays a detrimental role in cardiac remodeling, but its role in cardiac fibroblast (CF) function is not well defined. We aimed to identify the p38 MAPK subtypes expressed by human CF, study their activation in response to proinflammatory cytokines, and determine which subtypes were important for expression of specific cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of mRNA levels in human CF cultured from multiple patients revealed a consistent pattern of expression with p38α being most abundant, followed by p38γ, then p38δ and only low expression of p38β (3% of p38α mRNA levels). Immunoblotting confirmed marked protein expression of p38α, γ and δ, with little or no expression of p38β. Phospho-ELISA and combined immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting techniques demonstrated that the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α and TNFα selectively activated p38α and p38γ, but not p38δ. Selective p38α siRNA gene silencing reduced IL-1α-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 mRNA expression and protein secretion, without affecting IL-1α-induced IL-1β and MMP-9 mRNA expression.

In conclusion, human CF express the α, γ and δ subtypes of p38 MAPK, and the α subtype is important for IL-1α-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 expression in this cell type.

1. Introduction

Cardiac fibroblasts (CF) are the most populous cell type in the heart and are intricately involved in the cardiac remodeling process following myocardial infarction (MI) [1]. The tissue damage caused by MI triggers an acute inflammatory response, with rapidly elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and infiltration of inflammatory cells [2,3]. This leads to formation of granulation tissue which is rich in macrophages and myofibroblasts, the latter being derived from both resident CF and non-resident precursor cells [4]. Myofibroblasts invade the infarct area and degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) via activation of members of the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) family of proteolytic enzymes to facilitate removal of cell and tissue debris and promote neovascularization, prior to scar formation [2,3].

CF appear to be able to contribute to the inflammatory and granulation phases of post-MI remodeling by secreting a range of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and MMPs [1,5–8]. Interleukin (IL)-6 is secreted by CF from multiple species [1] and contributes to cardiac dysfunction by stimulating left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis [9]. CF can secrete several different MMPs, including MMP-1, -2, -3, -9 and -10 [7,8]. MMP-3 is a broad spectrum protease capable of cleaving several non-fibrillar extracellular matrix proteins as well as proteolytically activating other MMPs (e.g. MMP-2 and -9). Although not particularly well studied in the heart, MMP-3 appears to play a critical regulatory role in early remodeling post-MI [10].

There is strong in vivo evidence that activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family of stress-activated kinases exacerbates myocardial injury following prolonged ischemia [11]. Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), which are potent stimuli for the p38 MAPK pathway, are elevated in the infarcted heart and appear to be detrimental for post-MI myocardial remodeling and progression to heart failure [12]. There are four known subtypes of p38 MAPK; p38α, p38β, and the more distantly related p38γ and p38δ [13]. Each subtype is encoded by a separate gene and their expression is restricted to specific tissues and cell types. Importantly, much of the evidence supporting a role for p38 MAPK in promoting cardiac dysfunction and adverse remodeling has focused on its role in the cardiomyocyte, with comparatively little focus on the CF [14]. However, there is evidence that p38 MAPK signaling differs between cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts in vivo [15].

The aims of this study were to identify the p38 MAPK subtypes expressed by human CF, study their activation in response to proinflammatory cytokines, and determine which subtypes were important for mediating proinflammatory cytokine-induced increases in cytokine and MMP expression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

Right atrial appendage biopsies from multiple patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass surgery at the Leeds General Infirmary were obtained following local ethical committee approval and informed patient consent. Primary cultures of CF were harvested, cultured and characterized as myofibroblasts (alpha-smooth muscle actin- and vimentin-positive) as we have described previously [16–18]. Experiments were performed on early passage cells (P3–P5) from several different patients (indicated by n number). Cells were serum-starved by culturing in serum-free medium for 24 h before inclusion in experiments.

2.2. Immunoblotting

For p38 MAPK subtype expression analysis, whole cell homogenates were prepared from serum-starved CF from 5 different patients as described previously [19]. Homogenates of human saphenous vein endothelial cells, cultured as previously [20], were prepared as additional controls. Equal amounts of protein (40 μg) were resolved by SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting performed as described previously [19] with p38 subtype-specific antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-p38α (#2371, Cell Signaling Technology), goat polyclonal anti-p38β (#sc-6176, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse monoclonal anti-p38γ (#MAB1347, R&D Systems) and rabbit polyclonal anti-p38δ (#9214, Cell Signaling Technology). Expression of β-actin was assessed as a loading control using a mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (#ab8226, Abcam). Immunolabelled bands were visualized by SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescence kit (Perbio).

For signaling experiments, serum-starved CF were stimulated with recombinant human IL-1α (Invitrogen), TNFα (Invitrogen) or anisomycin (Sigma) in serum-free medium before preparing whole cell homogenates. Activation of components of the p38 pathway was determined by immunoblotting with phosphorylation state-specific antibodies for p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), MAPKAPK2 (Thr334), HSP27 (Ser82) and their corresponding expression antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology).

2.3. Quantitative RT-PCR

For p38 subtype expression analysis, cellular RNA was extracted from serum-starved CF from 8 different patients and cDNA prepared as described previously [21]. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System and intron-spanning human p38α (Hs00176247_m1), p38β (Hs00177101_m1), p38γ (Hs00268060_m1) and p38δ (Hs00559623_m1) primers and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems). Importantly, serial dilution of cDNA samples yielded comparable efficiencies for these different primer/probe sets, allowing meaningful comparison of expression levels between primer sets. Data are presented as percentage of GAPDH endogenous control mRNA expression (Hs99999905_m1 primers) using the formula 2−ΔCT × 100.

For analysis of cytokine and MMP mRNA expression, cellular RNA was extracted from cells at the end of the incubation period. Real-time RT-PCR was performed using intron-spanning human IL-6 (Hs00174131_m1), IL-1β (Hs00174097_m1), MMP-3 (Hs00233962_m1) and MMP-9 (Hs00234579_m1) primers and Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems). Data are presented as percentage of GAPDH expression using the formula 2−ΔCT × 100.

2.4. Measurement of p38 subtype phosphorylation

Serum-starved cells were stimulated for 30 min before assessing phosphorylation of p38 MAPK subtypes within the Thr∗–Gly–Tyr∗ activation site using two complementary methods; a combined immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting (IP/IB) assay and a phospho-ELISA. For the IP/IB assay, cells were extracted in lysis buffer comprising 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 μg/ml leupeptin. A pan phospho-specific p38 mouse monoclonal antibody (#9216, Cell Signaling Technology) and protein-G conjugated magnetic Dynabeads (Invitrogen) were employed to immunoprecipitate phosphorylated p38 subtypes before immunoblotting with individual p38 subtype expression antibodies.

For p38 ELISA studies, cells were extracted in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA, 6 M urea, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM sodium fluoride, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin, 100 μM PMSF, 3 μg/ml aprotinin, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. Colorimetric sandwich ELISAs (R&D Systems) were then employed to measure phosphorylation of p38α, γ and δ, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5. Gene silencing

ON-TARGETplus human p38α siRNA (containing 4 different targeted oligonucleotides) was purchased from Dharmacon. Cells were plated at ∼100,000 per well in 6-well plates and 24 h later were either mock-transfected (no siRNA) or transfected with 100 nM p38α siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 5 h, fresh growth medium was added to the cells before incubation for a further 4 days. For the final 16 h of the experiment, growth medium was replaced with fresh serum-free medium. Cells were then treated with appropriate stimuli before extracting RNA for RT-PCR or protein for immunoblotting.

2.6. IL-6 and MMP-3 ELISA

Conditioned media were collected 6 h (IL-6) or 24 h (MMP-3) after cell treatment, centrifuged to remove any detached cells and stored at −40 °C for subsequent analysis. ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Results are mean ± SEM with n representing the number of experiments on cells from different patients. Data were analyzed as ratios using either paired t-tests or repeated measures one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test (GraphPad Prism software, www.graphpad.com). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Expression and activation of p38 MAPK subtypes

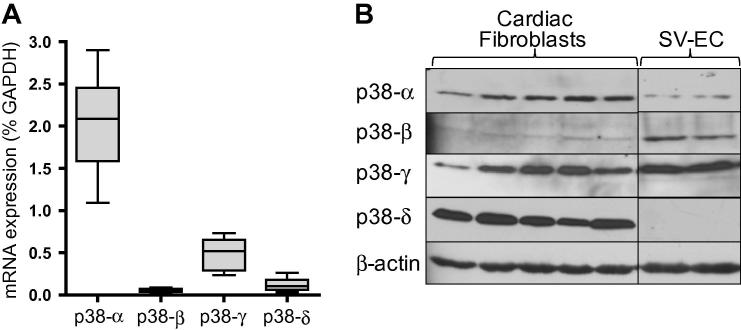

Expression of p38 subtypes in human CF was investigated by quantitative real-time RT-PCR and immunoblotting. Analysis of mRNA levels in cells from 8 different patients (Fig. 1A) revealed a consistent pattern of expression with p38α being most abundant (mean 2.0% of GAPDH mRNA levels), followed by p38γ (0.5%), p38δ (0.12%) and p38β (0.06%). Immunoblotting of CF homogenates from 5 further patients revealed marked protein expression of p38α, γ and δ, but little or no p38β was detected (Fig. 1B). As a positive control, we performed side-by-side analysis of p38 subtype protein expression in human vascular endothelial cells, which revealed significant expression of p38α, β and γ, but no p38δ (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

p38 MAPK subtype expression in human CF. (A) Relative mRNA levels for p38 subtypes in CF from 8 different patients quantified using real-time RT-PCR. Data are expressed as percentage of GAPDH mRNA levels (2−ΔCT × 100) and depicted as a box and whisker plot (box defines 25th–75th interquartile range, whiskers depict full range, and horizontal line is median). (B) Whole cell homogenates of CF (5 patients) or human saphenous vein endothelial cells (2 patients) were immunoblotted for expression of p38 subtypes. Blot reprobed with β-actin antibody to confirm equal loading.

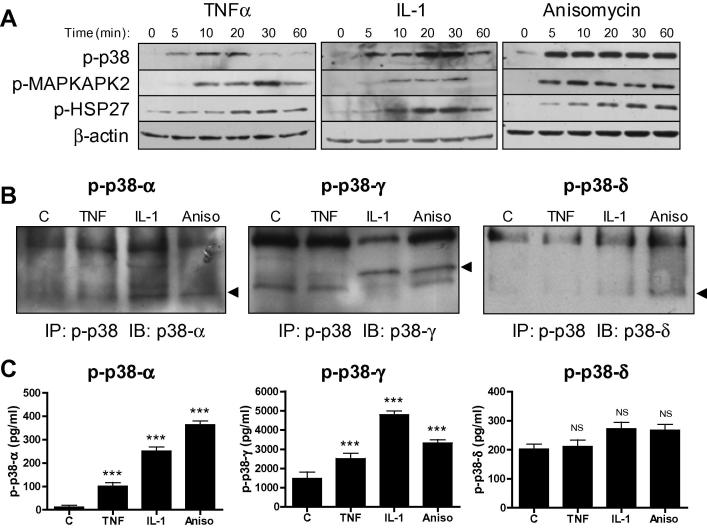

Phosphorylation site-specific antibodies were used to explore activation of classical downstream substrates of p38 MAPK in human CF (Fig. 2A). TNFα and IL-1α each stimulated p38 MAPK phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner. Phosphorylation of the downstream substrate MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2), and the MAPKAPK2 substrate heat shock protein (HSP) 27, was also observed in response to cytokine treatment. Rapid and robust phosphorylation of all components of the p38 MAPK pathway was evident following stimulation with anisomycin, used as a positive control (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Cytokine-induced p38 MAPK subtype activation in human CF. (A) Cells stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα, 10 ng/ml IL-1α or 25 μg/ml anisomycin for 5–60 min before preparing whole cell homogenates and immunoblotting with phospho-specific and expression antibodies for p38 MAPK, MAPKAPK2 and HSP27. Blots representative of n = 3. (B) CF stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα, 10 ng/ml IL-1α or 25 μg/ml anisomycin for 15 min before preparing cell extracts for analysis of p38 subtype phosphorylation by IP/IB method. Samples were immunoprecipitated with pan phospho-p38 antibody then immunoblotted with individual p38 subtype expression antibodies. Blots representative of n = 3. (C) CF stimulated as for (B) and p38 subtype phosphorylation analyzed by ELISA. Bar chart depicts concentration of phosphorylated p38 subtypes (pg/ml). ∗∗∗P < 0.001, NS = not significant for effect of stimulus compared with vehicle control (n = 6).

The ability of TNFα and IL-1α to stimulate p38α, γ and δ in CF was investigated using a combined IP/IB method (Fig. 2B) and a phospho-ELISA approach (Fig. 2C), which gave comparable results. Both TNFα and IL-1α increased phosphorylation of p38α and p38γ, with IL-1α being the more potent stimulus (Fig. 2B and C). Neither cytokine increased p38δ phosphorylation above basal levels.

3.2. Effect of p38α gene silencing on signaling and expression of cytokines and MMPs

We have previously demonstrated that TNFα and IL-1α potently induce expression of a number of proinflammatory cytokines in human CF (e.g. TNFα, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8) [5,6,21], as well as several MMPs (e.g. MMP-1, -3, -9 and -10) [8,22]. We also determined that IL-1α-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 mRNA expression was inhibited by the p38α/β inhibitor SB203580, whereas IL-1α-induced IL-1β and MMP-9 mRNA expression was not affected by SB203580 [5,8]. This information, together with the knowledge of subtype expression in CF, implicated p38α as the most likely subtype responsible for mediating IL-1α-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 mRNA expression in human CF. We therefore used a gene silencing strategy to selectively reduce expression of p38α and investigated the consequences at the level of cytokine and MMP expression.

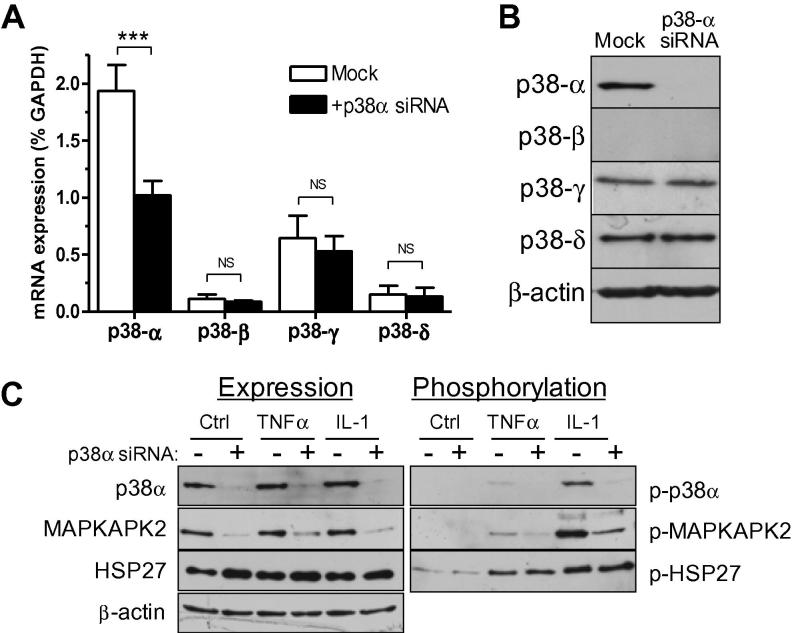

Pilot experiments determined that p38α mRNA levels were reduced by ∼90% compared with mock-transfected cells 24 h after transfection with appropriate siRNA oligonucleotides, followed by reduced protein levels consistently observed 4 days after transfection (data not shown). The effects of p38α gene silencing on cytokine-induced signaling and expression of cytokines and MMPs were therefore assessed 4 days after transfection with p38α siRNA. At this time point, p38α mRNA levels remained significantly reduced (by >50%) compared with mock-transfected cells (Fig. 3A) and protein levels were reduced by >90% (Fig. 3B). The specificity and selectivity of the gene silencing approach was confirmed by demonstrating that the three other p38 MAPK subtypes remained unaffected at the mRNA (Fig. 3A) and protein (Fig. 3B) levels following p38α gene silencing.

Fig. 3.

Effect of p38α gene silencing on p38 MAPK pathway signaling. Cells were mock-transfected or transfected with p38α siRNA before incubation for 4 days. (A) mRNA expression of p38 subtypes measured by RT-PCR. Data expressed as percentage GAPDH mRNA levels. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, NS = not significant (n = 5). (B) Protein expression of p38 subtypes measured in parallel cultures by immunoblotting. β-Actin blot confirmed equal protein loading. (C) Mock- or p38α siRNA-transfected CF stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNFα or IL-1α for 20 min. P38 MAPK, MAPKAPK2 and HSP27 phosphorylation and expression determined by immunoblotting. Blots reprobed with β-actin antibody to show equal loading.

We next studied activation of components of the p38 MAPK pathway in p38α-silenced cells (Fig. 3C). TNFα- and IL-1α-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation and MAPKAPK2 phosphorylation was markedly inhibited in siRNA-targeted cells in which p38α protein was knocked down (Fig. 3C). Interestingly, MAPKAPK2 protein expression was also significantly reduced in p38α-silenced cells (Fig. 3C). However, despite the marked loss of p38 and MAPKAPK2 signals, IL-1α-induced HSP27 phosphorylation remained relatively unaffected (Fig. 3C).

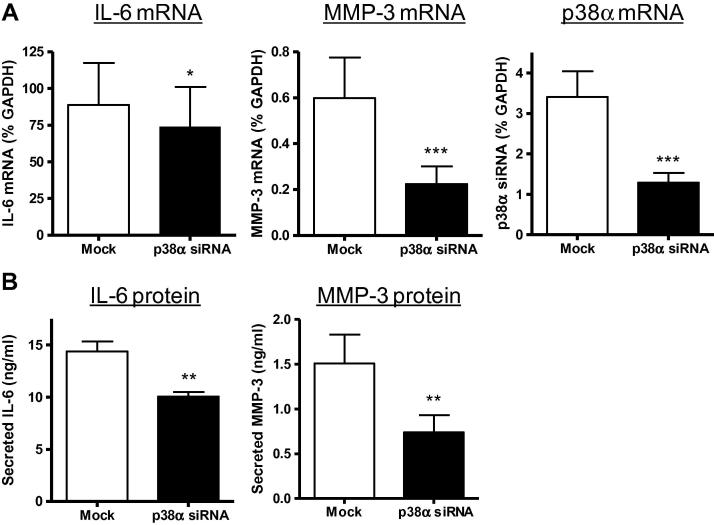

To investigate the effect of selective p38α silencing on IL-6 and MMP-3 expression, mock- or siRNA-transfected cells were incubated for 4 days prior to stimulation with IL-1α and quantification of mRNA levels and protein secretion after 6 h or 24 h respectively (Fig 4). IL-6 mRNA expression levels were reduced by 20% in p38α-silenced cells 6 h after IL-1α stimulation (Fig. 4A). In the same experiments, IL-1α-induced MMP-3 mRNA levels were reduced by 65% in p38α-silenced cells. By comparison, p38α siRNA had no effect on IL-1α-induced IL-1β mRNA levels (110 ± 16% of mock, P = 0.639, n = 3) or MMP-9 mRNA levels (99 ± 33% of mock, P = 0.734, n = 3); consistent with our previous demonstration of insensitivity to the p38α/β inhibitor SB203580 [5,8]. ELISA analysis of conditioned media (24 h) revealed significant inhibition of IL-1α-induced IL-6 secretion (30%) and IL-1α-induced MMP-3 secretion (50%) in p38α-silenced cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Effect of p38α gene silencing on IL-6 and MMP-3 expression. CF were mock-transfected (open bars) or transfected with p38α siRNA (filled bars), cultured for 4 days to promote p38α protein silencing, then stimulated with 10 ng/ml IL-1α for 6–24 h. (A) Real-time RT-PCR data for mRNA levels of IL-6, MMP-3 and p38α, expressed as percentage GAPDH mRNA levels. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗P < 0.05 for effect of gene silencing (6 h, n = 6). (B) ELISA analysis of IL-6 (6 h, n = 5) and MMP-3 (24 h, n = 4) protein levels in conditioned media from IL-1α treated cells. ∗∗P < 0.01 for effect of gene silencing.

4. Discussion

Previous studies have determined that the most highly expressed p38 subtype in the adult human heart is p38α, with lower levels of p38γ and p38δ, and no detectable p38β [23]. The major subtypes reported in mouse heart are p38α and p38γ [24]. Although it is known that cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes express at least three p38 subtypes (α, β and γ [25], the profile of p38 subtype expression in CF has not been previously described. We found that cultured human CF exhibited a similar profile to that reported for whole heart (i.e. p38α > γ > δ ≫ β). The lack of p38β protein expression in CF reflected the mRNA data and was not due to antibody inadequacy as control vascular endothelial cells exhibited demonstrable p38β expression.

In CF, both TNFα and IL-1α selectively stimulated p38α and p38γ phosphorylation, but did not activate p38δ. Both p38α and p38γ are activated in the remodeling heart following MI, with p38 phosphorylation being apparent in both myocytes and fibroblasts [15]. The increasing evidence that individual p38 MAPK subtypes regulate distinct cellular functions within the heart offers potential for CF-specific therapeutic strategies targeted at the p38 MAPK pathway [14].

We have previously reported that SB203580, a widely employed inhibitor of the α and β subtypes of p38 MAPK, can reduce IL-1α-induced IL-6 mRNA expression levels by 50% [5]. Indeed, several other studies in rat and mouse CF have also reported that SB203580 inhibits IL-6 expression in response to a range of inflammatory and non-inflammatory stimuli [14]. Although the inhibitory effect of p38α siRNA (20%) was less than that observed with pharmacological inhibition, it was consistently observed in cells from different patients. Overexpression of a dominant negative p38α mutant also reduced adenosine-induced IL-6 expression in rat CF by 50% [26]. IL-6 may therefore represent an important downstream target of the p38α pathway in the heart. Indeed, an in vivo study on mice with cardiac-specific overexpression of p38α revealed upregulation of over 260 genes, and IL-6 was identified as a key locus within this p38α signaling network [27].

In comparison with IL-6, much less is known about regulation of MMP-3 in CF. The MMP-3 gene promoter shares several structural similarities with the MMP-1 and MMP-9 promoters, including a TATA box, two AP-1 sites, a PEA3 site and an NF-B binding site [7]. Although IL-1 induces expression of several MMPs in human CF (including MMP-1, -3, -9 and -10), only IL-1-induced MMP-3 expression is inhibited by SB203580 [8]. In contrast, IL-1-induced MMP-3 expression in adult rat CF is reported to be p38-independent [28], raising the possibility of species-specific MMP-3 regulation in CF.

Not only did p38α gene silencing reduce expression of p38α, but it also reduced protein expression of the downstream substrate MAPKAPK2. A similar observation was reported in p38α siRNA-treated HUVECs [29]. Mice with homozygous ablation of the p38α gene die in utero due to defective placental development [30], but embryonic fibroblasts cultured from these mice also have markedly reduced MAPKAPK2 expression due to both transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation [31]. Thus, MAPKAPK2 expression is dependent on p38α expression. The converse also applies, as MAPKAPK2 knockout mice exhibit markedly reduced p38α protein expression [32], highlighting the intricate link between expression levels of these two molecules.

Although p38 inhibitors have been efficacious in pre-clinical studies and some early clinical trials, adverse side effects on liver and CNS function have prevented many progressing beyond Phase II [33]. This may reflect the critical role of p38 signaling in diverse cellular functions, the importance of p38 feedback signaling loops, or off-target effects of the inhibitors. Importantly, several trials are currently underway to investigate the effects of lower doses of p38 inhibitors on cardiovascular disease and its complications [14,34]. By furthering our understanding of the roles of individual p38 subtypes in cardiac function we may be able to identify alternative components of the p38 MAPK pathway that are more amenable to therapeutic intervention for reducing adverse myocardial remodeling.

In summary, we demonstrated that human CF express the α, γ and δ subtypes of p38 MAPK. IL-1α selectively activated both p38α and p38γ, but it was the α subtype of p38 that was important for IL-1α-induced IL-6 and MMP-3 expression. Hence, targeting p38α may be an attractive therapeutic approach for reducing specific aspects of the post-MI inflammatory response at the level of the CF.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a project grant from the British Heart Foundation (PG/06/012/20287), awarded to N.A.T. and K.E.P. The funding body was not involved in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. We are grateful to Phil Warburton for cell culture expertise.

References

- 1.Porter K.E., Turner N.A. Cardiac fibroblasts: at the heart of myocardial remodeling. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009;123:255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frangogiannis N.G., Smith C.W., Entman M.L. The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;53:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00434-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frangogiannis N.G., Entman M.L. Chemokines in myocardial ischemia. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2005;15:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Borne S.W., Diez J., Blankesteijn W.M., Verjans J., Hofstra L., Narula J. Myocardial remodeling after infarction: the role of myofibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010;7:30–37. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner N.A., Das A., Warburton P., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G., Porter K.E. Interleukin-1α stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human cardiac myofibroblasts. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H1117–H1127. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00372.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner N.A., Das A., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G., Porter K.E. Human cardiac fibroblasts express ICAM-1, E-selectin and CXC chemokines in response to proinflammatory cytokine stimulation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2011;43:1450–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turner N.A., Porter K.E. Regulation of myocardial matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity by cardiac fibroblasts. IUBMB Life. 2012;64:143–150. doi: 10.1002/iub.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner N.A., Warburton P., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G., Porter K.E. Modulatory effect of interleukin-1α on expression of structural matrix proteins, MMPs and TIMPs in human cardiac myofibroblasts: role of p38 MAP kinase. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melendez G.C., McLarty J.L., Levick S.P., Du Y., Janicki J.S., Brower G.L. Interleukin 6 mediates myocardial fibrosis, concentric hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction in rats. Hypertension. 2010;56:225–231. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.148635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee R., Bruce J.A., McClister D.M., Jr., Allen C.M., Sweterlitsch S.E., Saul J.P. Time-dependent changes in myocardial structure following discrete injury in mice deficient of matrix metalloproteinase-3. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005;39:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark J.E., Sarafraz N., Marber M.S. Potential of p38-MAPK inhibitors in the treatment of ischaemic heart disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;116:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aukrust P., Gullestad L., Ueland T., Damas J.K., Yndestad A. Inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in chronic heart failure: potential therapeutic implications. Ann. Med. 2005;37:74–85. doi: 10.1080/07853890510007232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyriakis J.M., Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner N.A. Therapeutic regulation of cardiac fibroblast function: targeting stress-activated protein kinase pathways. Fut. Cardiol. 2011;7:673–691. doi: 10.2217/fca.11.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh C.C., Li H., Malhotra D., Turcato S., Nicholas S., Tu R., Zhu B.Q., Cha J., Swigart P.M., Myagmar B.E., Baker A.J., Simpson P.C., Mann M.J. Distinctive ERK and p38 signaling in remote and infarcted myocardium during post-MI remodeling in the mouse. J. Cell. Biochem. 2010;109:1185–1191. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porter K.E., Turner N.A., O’Regan D.J., Balmforth A.J., Ball S.G. Simvastatin reduces human atrial myofibroblast proliferation independently of cholesterol lowering via inhibition of RhoA. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;61:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner N.A., Porter K.E., Smith W.H., White H.L., Ball S.G., Balmforth A.J. Chronic β2-adrenergic receptor stimulation increases proliferation of human cardiac fibroblasts via an autocrine mechanism. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;57:784–792. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00729-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mughal R.S., Warburton P., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G., Turner N.A., Porter K.E. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ-independent effects of thiazolidinediones on human cardiac myofibroblast function. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2009;36:478–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner N.A., Ball S.G., Balmforth A.J. The mechanism of angiotensin II-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 activation is independent of angiotensin AT1A receptor internalisation. Cell. Signalling. 2001;13:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aley P.K., Porter K.E., Boyle J.P., Kemp P.J., Peers C. Hypoxic modulation of Ca2+ signaling in human venous endothelial cells. Multiple roles for reactive oxygen species. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:13349–13354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turner N.A., Mughal R.S., Warburton P., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G., Porter K.E. Mechanism of TNFα-induced IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-6 expression in human cardiac fibroblasts: effects of statins and thiazolidinediones. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;76:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter K.E., Turner N.A., O’Regan D.J., Ball S.G. Tumor necrosis factor α induces human atrial myofibroblast proliferation, invasion and MMP-9 secretion: inhibition by simvastatin. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;64:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lemke L.E., Bloem L.J., Fouts R., Esterman M., Sandusky G., Vlahos C.J. Decreased p38 MAPK activity in end-stage failing human myocardium: p38 MAPKα is the predominant isoform expressed in human heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:1527–1540. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dingar D., Merlen C., Grandy S., Gillis M.A., Villeneuve L.R., Mamarbachi A.M., Fiset C., Allen B.G. Effect of pressure overload-induced hypertrophy on the expression and localization of p38 MAP kinase isoforms in the mouse heart. Cell. Signalling. 2010;22:1634–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Court N.W., dos Remedios C.G., Cordell J., Bogoyevitch M.A. Cardiac expression and subcellular localization of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase member stress-activated protein kinase-3 (SAPK3) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34:413–426. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng W., Song Y., Chen C., Lu Z.Z., Zhang Y. Stimulation of adenosine A2B receptors induces interleukin-6 secretion in cardiac fibroblasts via the PKC-δ-P38 signaling pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;159:1598–1607. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tenhunen O., Rysa J., Ilves M., Soini Y., Ruskoaho H., Leskinen H. Identification of cell cycle regulatory and inflammatory genes as predominant targets of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the heart. Circ. Res. 2006;99:485–493. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000238387.85144.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown R.D., Jones G.M., Laird R.E., Hudson P., Long C.S. Cytokines regulate matrix metalloproteinases and migration in cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans I.M., Britton G., Zachary I.C. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces heat shock protein (HSP) 27 serine 82 phosphorylation and endothelial tubulogenesis via protein kinase D and independent of p38 kinase. Cell. Signalling. 2008;20:1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mudgett J.S., Ding J., Guh-Siesel L., Chartrain N.A., Yang L., Gopal S., Shen M.M. Essential role for p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in placental angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10454–10459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudo T., Kawai K., Matsuzaki H., Osada H. P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase plays a key role in regulating MAPKAPK2 expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;337:415–421. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotlyarov A., Yannoni Y., Fritz S., Laass K., Telliez J.B., Pitman D., Lin L.L., Gaestel M. Distinct cellular functions of MK2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:4827–4835. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4827-4835.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen P. Targeting protein kinases for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:317–324. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marber M.S., Rose B., Wang Y. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-A potential target for intervention in infarction, hypertrophy, and heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2011;51:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]